Abstract

A cobalt-catalyzed method for the 1,1-diboration of terminal alkynes with bis(pinacolato)diboron (B2Pin2) is described. The reaction proceeds efficiently at 23 °C with excellent 1,1-selectivity and broad functional group tolerance. With the unsymmetrical diboron reagent PinB–BDan (Dan = naphthalene-1,8-diaminato), stereoselective 1,1-diboration provided products with two boron substituents that exhibit differential reactivity. One example prepared by diboration of 1-octyne was crystallized, and its stereochemistry established by X-ray crystallography. The utility and versatility of the 1,1-diborylalkene products was demonstrated in a number of synthetic applications, including a concise synthesis of the epilepsy medication tiagabine. In addition, a synthesis of 1,1,1-triborylalkanes was accomplished through cobalt-catalyzed hydroboration of 1,1-diborylalkenes with HBPin. Deuterium-labeling and stoichiometric experiments support a mechanism involving selective insertion of an alkynylboronate to a Co–B bond of a cobalt boryl complex to form a vinylcobalt intermediate. The latter was isolated and characterized by NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography. A competition experiment established that the reaction involves formation of free alkynylboronate and the two boryl substituents are not necessarily derived from the same diboron source.

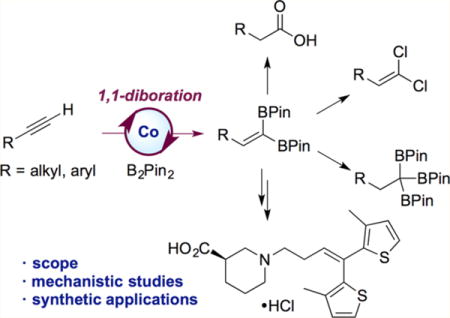

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Organoboron compounds are among the most versatile in organic synthesis, owing to their stability, ease of handling, and utility in the synthesis of carbon–carbon and carbon heteroatom bonds.1 Among this important class of reagents, alkenyldiboronates are particularly attractive because they offer two distinct boron substituents for elaboration, ideally in a site and stereoselective manner. As a consequence, alkenyldiboronates have found applications in the stereocontrolled synthesis of multisubstituted olefins,2 an important challenge in synthesis.3 Specifically, 1,2-diborylalkenes have been used as key intermediates en route to natural products4 and π-conjugated materials,5 while the utility of 1,1-diborylalkenes has been demonstrated in a concise synthesis of the anticancer agent tamoxifen.6

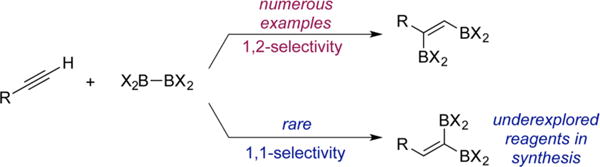

Synthesis of alkenyldiboronates is typically accomplished by diboration of terminal or internal alkynes and is often promoted by transition-metal catalysts,7 base,8 Lewis acid,9 and in some cases proceeds in the absence of catalysts.10 Regardless of the synthetic route, these methods almost exclusively result in 1,2-difunctionalization,11 a common reactivity mode for addition to C–C multiple bonds (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

1,2 vs 1,1-Selectivity in Alkyne Diboration

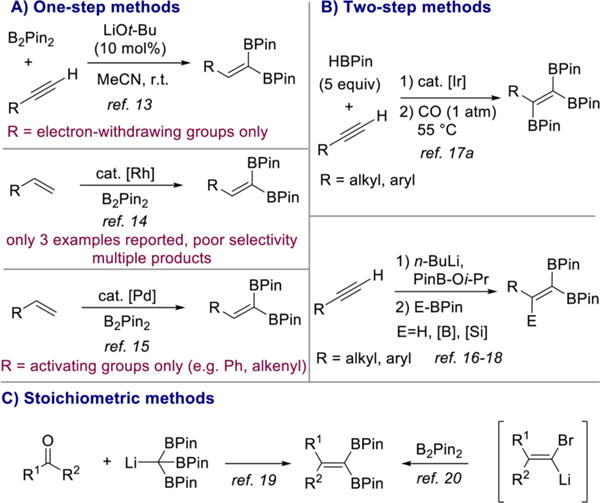

Since Miyaura and Suzuki’s seminal discovery of platinum-catalyzed alkyne 1,2-diboration,12 a number of catalysts for this transformation have been reported. By contrast, examples of the direct synthesis of the isomeric 1,1-diborylalkenes from terminal alkynes and diboron reagents are rare. In addition, the full potential of 1,1-diborylalkenes in synthesis has not been explored beyond the singular tamoxifen example, even though these reagents offer a significant degree of synthetic flexibility. In 2015, Sawamura and co-workers reported the direct preparation of 1,1-diborylalkenes from terminal alkynes and B2Pin2 using LiOt-Bu as the catalyst (Scheme 2A).13 While effective and an important advance, this reaction is limited to alkynes bearing electron-withdrawing substituents such as propiolates.

Scheme 2.

Summary of Current Methods for the Synthesis of 1,1-Diborylalkenes

Rhodium-catalyzed dehydrogenative borylation of alkenes has been reported as a route to 1,1-diborylalkenes, but the selectivity is poor as mixtures of (di)borylated products were obtained and high temperatures were required.14 A more selective palladium-catalyzed method has since been described but is restricted to terminal alkenes bearing electronically activating groups such as aryl and alkenyl substituents (Scheme 2A).15

Two-step procedures starting from terminal alkynes (Scheme 2B)16–18 and methods involving stoichiometric amounts of organolithium reagents (Scheme 2C) have also been reported.19,20 However, these approaches suffer from low volumetric throughput and poor functional group compatibility, respectively. Given the limitations of the methods currently available for the synthesis of 1,1-diborylalkenes, the direct 1,1-diboration of terminal alkynes with simple alkyl and aryl substituents would be an attractive, atom economical method for the synthesis of these valuable building blocks and likely open new avenues for synthesis.

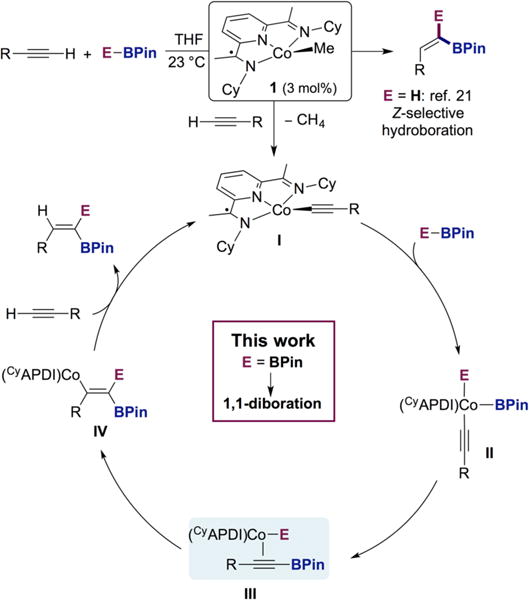

Our laboratory recently reported that the cyclohexyl-substituted pyridine(diimine) cobalt methyl complex 1 promotes the Z-selective hydroboration of terminal alkynes (Scheme 3).21 Stoichiometric experiments, isolation of intermediates, and deuterium-labeling studies established a unique mechanistic pathway involving initial formation of a cobalt acetylide (I) which, following engagement with pinacolborane (HBPin), forms an alkynylboronate complex (III). Regioselective syn-hydrocobaltation forms vinylcobalt intermediate (IV, E = H), resulting in the unusual Z-selectivity. The cyclohexyl-substituents were found to be important for the observed reactivity and formation of the key cobalt-acetylide intermediate. Analogous experiments with aryl-substituted bis(imino)pyridine cobalt compounds resulted in E-selective alkyne hydroboration due to preferential formation of the cobalt hydride over the cobalt acetylide. In the Z-selective method, the [H] and [BPin] of the borane are both transferred to the terminal carbon of the alkyne, suggesting that complex 1 may serve as a precatalyst for other cobalt-catalyzed 1,1-difunctionalization methods.22 Specifically, replacement of HBPin with B2Pin2 would generate a cobalt boryl intermediate (III), which after syn-borylcobaltation and product release would result in a method for the direct synthesis of 1,1-diborylalkenes (I–IV, E = BPin).

Scheme 3.

Proposed Mechanism for Z-Selective Hydroboration As Inspiration for the 1,1-Diboration of Terminal Alkynes

Here we describe a cobalt-catalyzed method for the synthesis of 1,1-diborylalkenes from readily available terminal alkynes and diboron reagents. In contrast to all other transition-metal-catalyzed diborations reported to date, the cobalt-catalyzed reaction documented here proceeds with excellent 1,1-selectivity. The new method exhibits broad scope and functional group tolerance, and its utility and mildness was demonstrated in a concise synthesis of tiagabine, a medication for the treatment of epilepsy. To highlight the synthetic versatility of the 1,1-diborylalkene products, they were used to access a diverse set of structural motifs, including 1,1-dihaloalkenes, a carboxylic acid, a 1,1-diborylalkane, and 1,1,1-triborylalkanes. In addition, the method could be extended to stereoselective synthesis of trisubstituted olefins through 1,1-diboration of terminal alkynes with the mixed diboron reagent PinB–BDan. The chemically differentiated boron substituents allowed selective cross coupling at [BPin]. Finally, mechanistic studies established the intermediacy of a cobalt vinyl intermediate that was crystallographically characterized.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

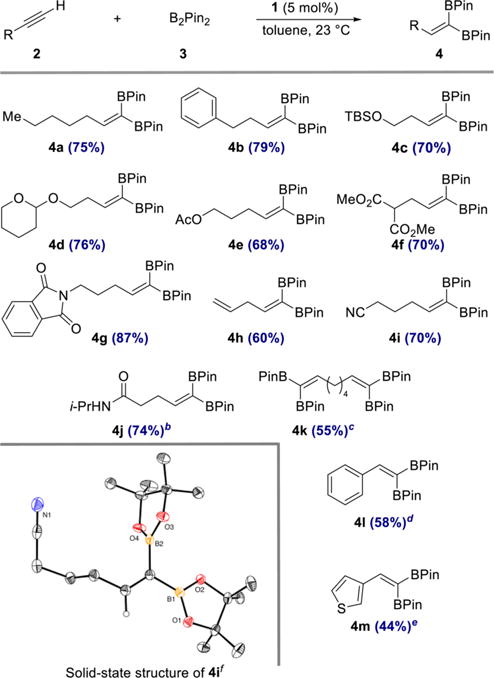

Initial catalyst evaluation was conducted with equimolar quantities of 1-heptyne and B2Pin2 in the presence of 5 mol % of 1 at 23 °C for 13 h in a 1.0 M toluene solution. Analysis of the unpurified reaction mixture by 1H NMR spectroscopy established clean and complete conversion to 1,1-diborylalkene 4a, which was isolated in 75% yield (Scheme 4). A control experiment demonstrated that no 1,1-diborylalkene product formed in the absence of cobalt complex 1. As shown in Scheme 4, a range of alkynes participated in cobalt-catalyzed 1,1-diboration to yield 1,1-diborylalkene products 4b–4m. Common organic functional groups such as tert-butyldime-thylsilyl ether (4c), acetal (4d), ester (4e, 4f), phthalimide (4g), nitrile (4i), and secondary amides (4j) were all compatible with the reaction conditions. Remarkably, a substrate bearing a terminal olefin underwent chemoselective 1,1-diboration of the alkyne without isomerization of the double bond (4h).

Scheme 4. Scope of the 1,1-Diboration of Terminal Alkynes with B2Pin2 and (CyAPDI)CoCH3 (1)a.

aReaction conditions: alkyne 2 (0.50 mmol), B2Pin2 (0.50 mmol, 1.0 equiv), 1 (0.025 mmol, 5 mol %), toluene (0.5 mL), 23 °C. Numbers in parentheses are yields of isolated products obtained after purification by flash chromatography on silica gel. b0.25 mmol 2, 0.25 mmol 3, 10 mol % 1. c2.0 equiv 3. d4.0 equiv 3. e1.5 equiv 3. fThermal ellipsoids at 50% probability.

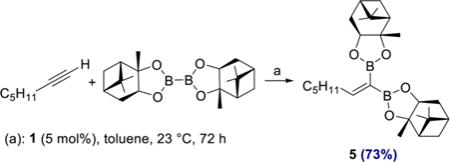

Aryl- and heteroaryl acetylenes also were suitable substrates (4l, 4m), although increased amounts of diboron reagent were required to suppress competitive homodimerization of the alkynes to the corresponding enynes. It is noteworthy that this side reaction was not observed when alkyl-substituted alkynes were used (4a–4k). To highlight the practicality of the method, products 4a and 4g were prepared on gram scale in 68 and 81% yield, respectively, with a reduced catalyst loading of 2 mol % (see SI for details). Diboron reagents other than B2Pin2 also participated in the catalytic reaction (eq 1), and cobalt-catalyzed reaction of 1-heptyne with bis[(+)-pinanediolato]-diboron afforded 1,1-diborylalkene 5 in 73% yield.

|

(1) |

Stereoselective 1,1-Diboration

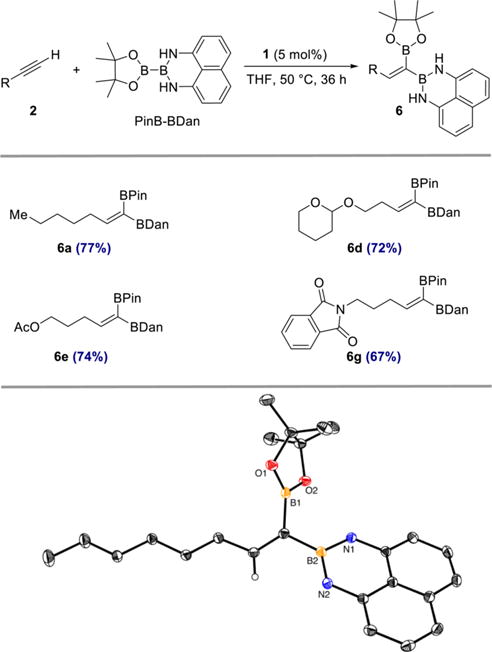

The stereocontrolled synthesis of alkenes is fundamentally important in organic synthesis.3 In this context, a stereoselective cobalt-catalyzed 1,1-diboration with an unsymmetrical diboron reagent would result in the formation of a trisubstituted olefin of well-defined configuration, providing access to an underexplored class of diborylalkenes. In 2010, Iwadate and Suginome reported the use of PinB–BDan (Dan = naphthalene-1,8-diaminato) in Pt-and Ir-catalyzed 1,2-diboration of alkynes.2d The reaction was regioselective, leading to exclusive transfer of the [BDan] substituent to the terminal carbon. As shown in Scheme 5, cobalt-catalyzed 1,1-diboration of 1-heptyne with PinB–BDan proceeded efficiently and stereoselectively to afford 6a in 77% yield. A related 1,1-diborylalkene derived from 1-octyne and PinB–BDan was also prepared and crystallized. Its structure and stereochemistry were confirmed by X-ray crystallography (Scheme 5, bottom). The generality and functional group compatibility of this stereoselective process was demonstrated with selected, representative alkyne substrates bearing common functional groups to afford products 6d, 6e, and 6g (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5. Stereoselective Cobalt-Catalyzed 1,1-Diboration of Terminal Alkynes with PinB−BDana.

aReagents and conditions: alkyne 2 (0.50 mmol), PinB–BDan (0.50 mmol), 1 (5 mol %), THF, 50 °C, 36 h. Numbers in parentheses are yields of isolated products obtained after purification by flash chromatography on silica gel. Thermal ellipsoids in ORTEP diagram at 50% probability; hydrogen atoms except vinyl C–H omitted for clarity. Olefin geometry of products 6a, 6d, 6e, and 6g assigned by analogy to the solid-state structure.

The differential reactivity of the two boron substituents in 6a allowed selective Suzuki–Miyaura cross coupling at BPin to proceed efficiently, furnishing 7 in 78% yield (eq 2). The olefin geometry in 7 was confirmed by NOESY (see SI). From a synthetic perspective, the two-step sequence of 1,1-diboration and cross coupling to give 7 represents a formal 1,1-carboboration of 1-heptyne.23

|

(2) |

Synthetic Applications of 1,1-Diborylalkenes

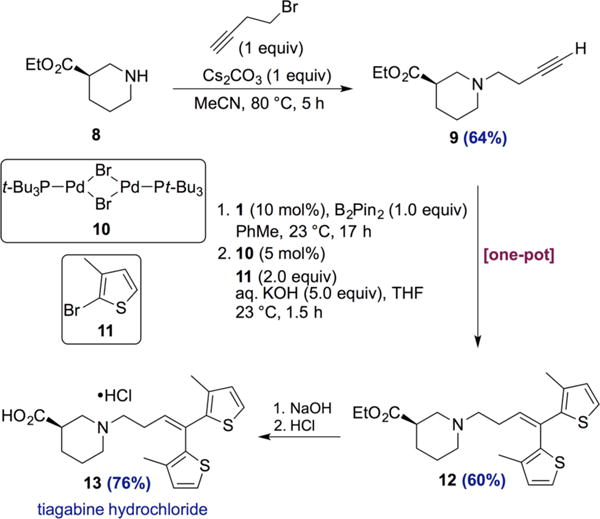

The synthetic utility of the 1,1-diboration method was demonstrated as an enabling step in the highly concise synthesis of tiagabine (13), an epilepsy medication (Scheme 6). Alkylation of commercially available (R)-ethylpiperidine-3-carboxylate (8) with 4-bromo-1-butyne gave terminal alkyne 9 in 64% yield. A one-pot sequence consisting of cobalt-catalyzed 1,1-diboration followed by Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling yielded tiagabine ethyl ester 12 in 60% yield over 2 steps. Importantly, the reaction conditions were compatible with the ester and amine functionality, and the integrity of the stereogenic center was preserved throughout the sequence of reactions (see SI for SFC traces). Ethyl ester 12 was then converted to tiagabine hydrochloride via a known series of steps involving saponification of the ester and formation of the hydrochloride salt.24

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of Tiagabine Hydrochloride via One-Pot 1,1-Diboration/Cross-Coupling

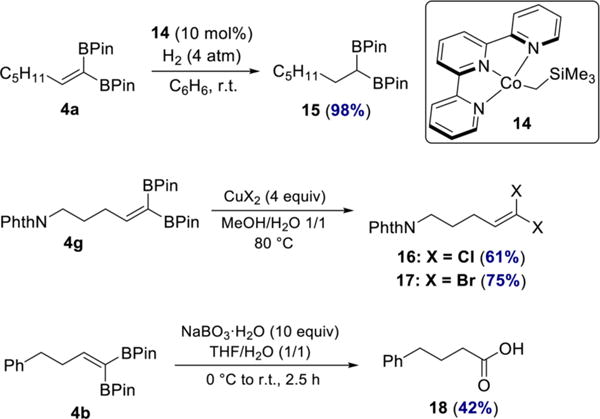

To highlight the versatility of the 1,1-diborylalkene products, they were also elaborated to other useful building blocks (Scheme 7). Hydrogenation of 4a catalyzed by terpyridine-ligated cobalt complex 14 afforded the corresponding 1,1-diborylalkane 15 in 98% yield. 1,1-Diborylalkanes have recently received increasing attention due to their utility in cross-coupling and alkylation reactions.25 In addition, 1,1-dichloro- and 1,1-dibromoolefins 16 and 17 were prepared by treating 4g with the appropriate cupric salt. The 1,1-dihaloolefin motif is found in a number of commercial insecticides26 as well as in natural products.27 Oxidation of 1,1-diborylalkene 4b with sodium perborate furnished carboxylic acid 18. The sequence of 1,1-diboration/oxidation is thus formally equivalent to oxidative hydration of a terminal alkyne.28 Importantly, the transformations yielding products 16–18 have not been previously reported.

Scheme 7.

Synthetic Applications of 1,1-Diborylalkenes

Synthesis of 1,1,1-Triborylalkanes

The use of 1,1-diborylalkenes in the synthesis of an unusual class of organoboron compounds was also explored. Selective hydroboration of 1,1-diborylalkenes would provide a unique route to 1,1,1-triborylalkanes, an underexplored class of reagents with considerable potential in organic synthesis. Huang recently reported high yields in deborylative alkylation reactions between 1,1,1-triborylalkanes and simple alkyl bromides,29a while our own laboratory demonstrated the utility of benzyltriboronates in diastereoselective conjugate additions.29b While the synthesis and reactivity of 1,1-diborylalkanes have received considerable attention due to their aforementioned utility in cross-coupling and alkylation reactions,25 the chemistry of the corresponding 1,1,1-triboronates is by comparison much less developed. This is likely due to the paucity of reliable and general synthetic methods for their synthesis. More than four decades ago, Matteson reported a synthesis of triborylmethane by reaction of chloroform with ClB(OR)2 in the presence of lithium metal.19,30 All methods developed since have been limited to narrow sets of substrates, such as derivatives of 2-ethylpyridine,31 styrene,29,32 or toluene.33 Accordingly, a two-step, one-pot sequence consisting of Co-catalyzed 1,1-diboration of terminal alkynes followed by selective hydroboration would provide a general synthesis of 1,1,1-triboronates with a set of structurally diverse alkyl groups attached to the triborylated carbon.

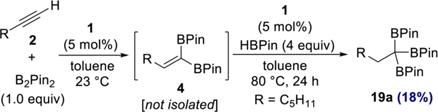

In an initial experiment, an additional 5 mol % cobalt complex 1 and HBPin (4 equiv) were added to a 1,1-diboration reaction of 1-heptyne that had reached completion, as judged by GC analysis. Although a new product was observed by GC analysis after a few hours, the reaction was sluggish. Heating the reaction mixture to 80 °C resulted in increased conversion, and the major product, 1,1,1-triboronate 19a, was isolated in 18% yield after 24 h (eq 3).

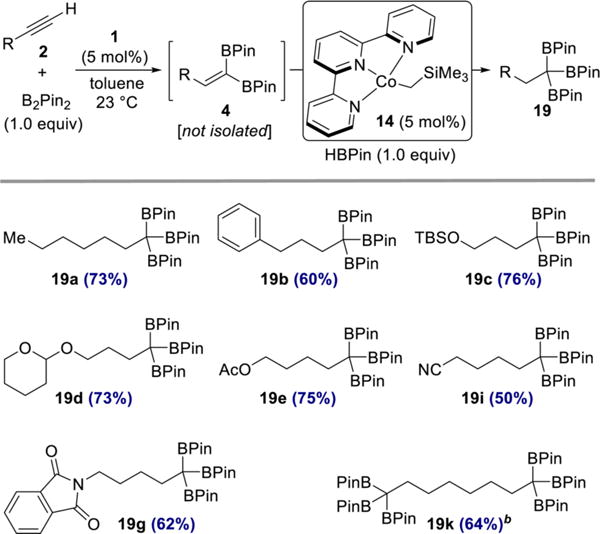

Having established that selective cobalt-catalyzed hydroboration of 1,1-diborylalkenes was possible, a more active alkene hydroboration catalyst was sought. Our laboratory recently reported a terpyridine cobalt complex that is active for the hydroboration of unactivated, trisubstituted alkenes,34 a relatively challenging class of substrates. Use of this complex in the hydroboration of styrene led to branched selectivity,34 likely involving a benzylcobalt intermediate. Accordingly, its use with 1,1-diborylalkenes could proceed via intermediacy of a stabilized α-borylcobalt intermediate.35 As shown in Scheme 8, sequential 1,1-diboration-hydroboration of terminal alkynes involving (CyAPDI)CoCH3 (1) and (Terpy)Co(CH2SiMe3) (14)34 furnished a collection of 1,1,1-triboronates 19 in 50–76% yield over two steps. Importantly, carbonyl-based functional groups were compatible with this hydroboration protocol, as evidenced by the synthesis of triboronates 19e, 19i, and 19g.

|

(3) |

Scheme 8. One-Pot, Sequential 1,1-Diboration−Hydroboration of Terminal Alkynesa.

aReaction conditions: alkyne 2 (0.50 mmol), B2Pin2 (0.50 mmol, 1.0 equiv), 1 (0.025 mmol, 5 mol %), toluene (0.5 mL), 23 °C; then 14 (0.025 mmol, 5 mol %), HBPin (0.50 mmol, 1.0 equiv). Numbers in parentheses are yields of isolated products after purification by flash chromatography on silica gel. b2 equiv of B2Pin2 and HBPin were used.

Mechanistic Studies

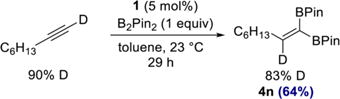

Having established the scope and utility of the 1,1-diboration method, attention was devoted toward understanding the mechanistic features of the transformation. Cobalt-catalyzed 1,1-diboration of 1-d1-octyne (90% isotopic purity) with B2Pin2 furnished 1,1-diborylalkene 4n with the deuterium label at the internal alkene carbon, as judged by 1H and quantitative 13C NMR spectroscopy (eq 4). This result is consistent with the mechanism depicted in Scheme 3.

|

(4) |

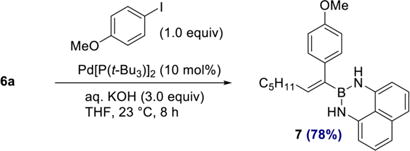

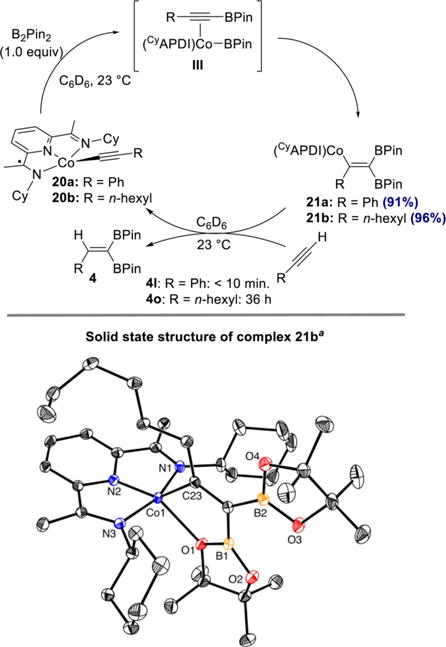

A set of stoichiometric experiments aimed at observing and isolating the proposed vinylcobalt intermediates were also conducted. Cobalt acetylide complexes 20a and 20b, derived from phenylacetylene and 1-octyne, respectively, were prepared by a previously described procedure.21 As shown in Scheme 9, treatment of cobalt acetylide complex 20a with 1 equiv of B2Pin2 in benzene-d6 cleanly generated a single new species within 60 h, as judged by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy. In contrast, the reaction of 20b with B2Pin2 to give vinylcobalt 21b proceeded to 95% conversion within 4 h. Recrystallization of vinylcobalt complex 21b from pentane at −35 °C yielded single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis. A representation of the solid-state structure is presented in Scheme 9 (bottom). The cobalt is five-coordinate with a coordination sphere defined by the tridentate pyridine(diimine), the carbon of the alkenyl group, and an oxygen (d(Co–O) = 2.2071(12) Å) of the syn-[BPin] substituent. The bond distances of the bis(imino)pyridine are consistent with one-electron reduction,36 as evidenced by the slightly elongated Cimine–Nimine bonds of 1.326(2) Å and 1.334(2) Å as well as the slightly contracted Cimine–Cipso bonds of 1.438(2) Å and 1.431(2) Å.

Scheme 9. Synthesis of Vinylcobalt Complexes, Solid-State Structure of 21b and Single-Turnover Experimentsa.

aThermal ellipsoids at 50% probability. Hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity.

To assess its catalytic competence, complex 21a was treated with 1 equiv of phenylacetylene, and analysis by 1H NMR spectroscopy established the presence of only cobalt acetylide 20a and 1,1-diborylalkene 4l, with vinylcobalt 21a having been completely consumed within 10 min. The analogous experiment with complex 21b and 1 equiv of 1-octyne resulted in slow conversion to the cobalt acetylide 20b and 1,1-diborylalkene 4o over the course of approximately 36 h. These results indicate that the relative rates of the individual steps (formation of vinylcobalt and protonation) are dependent on the identity of the alkyne. With aliphatic alkynes such as 1-octyne, the protonation is likely rate-determining, as was observed in the previously reported Z-selective hydroboration.21 In contrast, with more acidic alkynes such as phenylacetylene, the protonation step is comparatively fast, such that formation of the vinylcobalt complex is likely rate-determining.

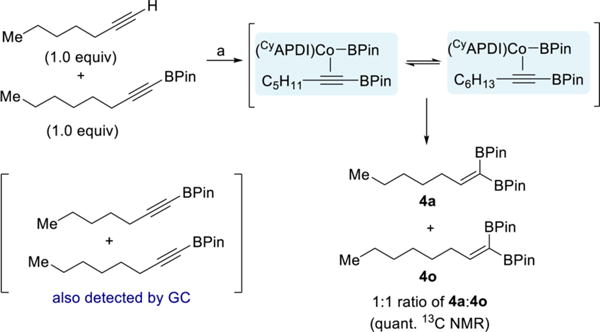

The intermediacy of a cobalt-alkynylboronate complex (III) was probed with a competition experiment. If dissociation of the alkynylboronate is competitive with insertion, then the two BPin substituents in the product may not necessarily be derived from the same molecule of B2Pin2. Indeed, cobalt-catalyzed reaction of 1-heptyne with 1 equiv of B2Pin2 in the presence of 1 equiv of 1-octynyl-BPin resulted in formation of a 1:1 ratio of the two 1,1-diborylalkene products 4a and 4o (Scheme 10). In addition, both alkynylboronates were observed by GC analysis upon complete consumption of B2Pin2. This result is consistent with alkynylboronates being intermediates en route to the 1,1-diborylalkenes and confirms that the alkynylboronate is labile in the presence of excess alkynylboronate.

Scheme 10. Competition Experiment Probing Formation of Free Alkynylboronatea.

aReagents and conditions: (a) 1-heptyne (0.50 mmol), 1-octynyl-BPin (0.50 mmol), B2Pin2 (0.50 mmol), 1 (5 mol %), toluene (0.5 mL), 23 °C, 15 h.

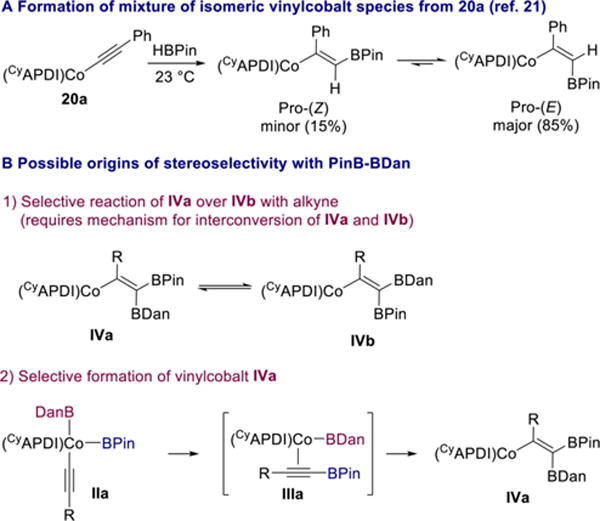

In the cobalt-catalyzed Z-selective hydroboration of alkynes with HBPin, a mixture of (Z) and (E)-vinylcobalt species was formed upon addition of HBPin to acetylide complex 20a and found to interconvert (Scheme 11A).21 The high stereo-selectivity observed in the 1,1-diboration with PinB–BDan could be a result of selective reaction of one vinylcobalt intermediate over another (IVa vs IVb), but is also consistent with the more Lewis acidic boron substituent (BPin)37 being transferred to the alkyne first and the resulting alkynyl–BPin cobalt complex (IIIa) undergoing syn-borylcobaltation to give IVa selectively (Scheme 11B).

Scheme 11.

Mechanistic Possibilities for the Origin of Stereoselectivity

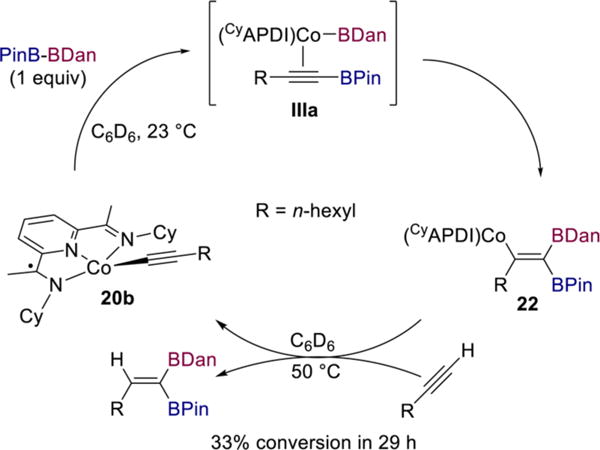

In the latter scenario, the structure of or relative rates of reductive elimination from complex IIa could affect what type of alkynylboronate complex (e.g., IIIa) forms. A stoichiometric experiment was performed to probe this question. Treatment of cobalt acetylide 20b with 1 equiv of PinB–BDan in benzene-d6 at room temperature resulted in formation of a single new species, as judged by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy (Scheme 12). Addition of 1 equiv of 1-octyne to 22 in benzene-d6 at room temperature resulted in only 5% conversion to diborylalkene product and complex 20b over the course of 18 h. However, after heating the solution in the NMR tube to 50 °C for 29 h, a 33/66 mixture of 20b/22 along with a single diborylalkene product was detected by 1H NMR spectroscopy. This result is consistent with the requirement for heating 1,1-diborations with PinB–BDan and indicates that the protonation step is considerably slower when the vinylcobalt bears a BDan substituent instead of BPin. The observation of a single new species upon addition of PinB–BDan to 20b suggests that stereoselective formation of vinylcobalt 22 may be the origin of the overall high stereoselectivity of the process.

Scheme 12.

Stereoselective Synthesis of Vinylcobalt Species 22 and Single-Turnover Experiment

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In summary, a general method for the 1,1-diboration of terminal alkynes catalyzed by a cyclohexyl-substituted pyridine diimine cobalt complex has been developed. The reaction proceeds under mild conditions, displays broad scope and functional group tolerance, and furnishes 1,1-diborylalkene products with excellent selectivity. Chiral as well as unsymmetrical diboron reagents participate in the reaction, and the latter furnished alkene products with two different boron substituents in stereoselective fashion. When used in tandem with Pd-catalyzed cross coupling, this resulted in a formal 1,1-carboboration of the terminal alkyne. A one-pot 1,1-diboration/cross-coupling sequence enabled a highly concise synthesis of tiagabine, an approved treatment for epilepsy. The synthetic versatility of the 1,1-diborylalkene products was further demonstrated in C–halogen, C–O, C–H, and C–B bond formation. The latter gave access to a set of 1,1,1-triborylalkanes that are inaccessible by existing methods. Mechanistic studies revealed that the 1,1-diboration proceeds via the intermediacy of a vinylcobalt species, in analogy to the previously reported Z-selective hydroboration and suggest this approach may be general for 1,1-difunctionalization strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

S.K. gratefully acknowledges the Swiss National Science Foundation for a postdoctoral fellowship. M.J.B. thanks the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada for a predoctoral fellowship (PGS-D). We are grateful to W. Neil Palmer and Jennifer V. Obligacion for insightful discussions. We also thank Dr. Istvań Pelczer for assistance with NMR spectroscopy as well as Dr. Charles Campana (Bruker) for assistance with solving the X-ray structure shown in Scheme 5. The staff at Lotus Separations are gratefully acknowledged for measuring the ee of 12. Financial support was provided by NIH (R01 GM121441).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.7b00445.

Crystallographic information (CIF)

Experimental details, characterization data, NMR spectra (PDF)

ORCID

Paul J. Chirik: 0000-0001-8473-2898

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.(a) Fernández E, Whiting A, editors. Synthesis and Application of Organoboron Compounds. Springer; Berlin: 2015. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hall DG, editor. Boronic Acids. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2011. [Google Scholar]; (c) Miyaura N, Suzuki A. Chem Rev. 1995;95:2457. [Google Scholar]; (d) Miyaura N. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2008;81:1535. [Google Scholar]

- 2.For selected key examples, see:; (a) Ishiyama T, Yamamoto M, Miyaura N. Chem Lett. 1996;25:1117. [Google Scholar]; (b) Brown SD, Armstrong RW. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:6331. [Google Scholar]; (c) Brown SD, Armstrong RW. J Org Chem. 1997;62:7076. doi: 10.1021/jo9711807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Iwadate N, Suginome M. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2548. doi: 10.1021/ja1000642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For a review, see:; (e) Iwasaki M, Nishihara Y. Chem Rec. 2016;16:2031. doi: 10.1002/tcr.201600017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Wang J, editor. Stereoselective Alkene Synthesis in Topics in Current Chemistry. Springer; Berlin: 2012. [Google Scholar]; (b) Negishi E, Huang Z, Wang G, Mohan S, Wang C, Hattori H. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1474. doi: 10.1021/ar800038e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SJ, Gray KC, Paek JS, Burke MD. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:466. doi: 10.1021/ja078129x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Shimizu M, Nagao I, Tomioka Y, Hiyama T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:8096. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yavari K, Moussa S, Hassine BB, Retailleau P, Voituriez A, Marinetti A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:6748. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimizu M, Nakamaki C, Shimono K, Schelper M, Kurahashi T, Hiyama T. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12506. doi: 10.1021/ja054484g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.For reviews, see:; (a) Yoshida H. ACS Catal. 2016;6:1799. [Google Scholar]; (b) Barbeyron R, Benedetti E, Cossy J, Vasseur JJ, Arseniyadis S, Smietana M. Tetrahedron. 2014;70:8431. [Google Scholar]; (c) Takaya J, Iwasawa N. ACS Catal. 2012;2:1993. [Google Scholar]; for a review on diboron(4) compounds and their synthetic applications, including alkyne diboration, see:; (d) Neeve EC, Geier SJ, Mkhalid IAI, Westcott SA, Marder TB. Chem Rev. 2016;116:9091. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For representative examples involving particular metals, see: Co:; (e) Adams CJ, Baber RA, Batsanov AS, Bramham G, Charmant JPH, Haddow MF, Howard JAK, Lam WH, Lin Z, Marder TB, Norman NC, Orpen AG. Dalton Trans. 2006;1370 doi: 10.1039/b516594f. Au. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Chen Q, Zhao J, Ishikawa Y, Asao N, Yamamoto Y, Jin T. Org Lett. 2013;15:5766. doi: 10.1021/ol4028013. Fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Nakagawa N, Hatakeyama T, Nakamura M. Chem - Eur J. 2015;21:4257. doi: 10.1002/chem.201406595. Cu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Yoshida H, Kawashima S, Takemoto Y, Okada K, Ohshita J, Takaki K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:235. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Nagao K, Ohmiya H, Sawamura M. Org Lett. 2015;17:1304. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For an example of base-mediated 1,2-diboration with trans-selectivity, see:; (b) Nagashima Y, Hirano K, Takita R, Uchiyama M. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:8532. doi: 10.1021/ja5036754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For an example of organosulfide-catalyzed 1,2-diboration of terminal alkynes under irradiation with light, see:; (c) Yoshimura A, Takamachi Y, Han LB, Ogawa A. Chem - Eur J. 2015;21:13930. doi: 10.1002/chem.201502425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herberich GE, Ganter C, Wesemann L. Chem Ber. 1990;123:49. [Google Scholar]

- 10.For a seminal report, see:; (a) Urry G, Kerrigan J, Parsons TD, Schlesinger HI. J Am Chem Soc. 1954;76:5299. [Google Scholar]; For a recent example, see:; (b) Kojima C, Lee KH, Lin Z, Yamashita M. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:6662. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uncatalyzed diborations of trimethylsilyl-, trialkylstannyl-, and trimethylgermylacetylenes with 1,2-dichlorodiboron(4) reagents have in select cases been shown to lead to formation of 1,1-diborylalkenes, possibly via rearrangement of an initially formed 1,2-adduct:; (a) Klusik H, Pues C, Berndt A. Z Naturforsch B: J Chem Sci. 1984;39:1042. [Google Scholar]; (b) Siebert W, Hildenbrand M, Hornbach P, Karger G, Pritzkow H. Z Naturforsch B: J Chem Sci. 1989;44:1179. [Google Scholar]; (c) Schulz H, Pritzkow H, Siebert W. Z Naturforsch B: J Chem Sci. 1993;48:719. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishiyama T, Matsuda N, Miyaura N, Suzuki A. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:11018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morinaga A, Nagao K, Ohmiya H, Sawamura M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:15859. doi: 10.1002/anie.201509218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Coapes RB, Souza FES, Thomas RL, Hall JJ, Marder TB. Chem Commun. 2003;614 doi: 10.1039/b211789d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mkhalid IAI, Coapes RB, Edes SN, Coventry DN, Souza FES, Thomas RL, Hall JJ, Bi SW, Lin Z, Marder TB. Dalton Trans. 2008;1055 doi: 10.1039/b715584k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Takaya J, Kirai N, Iwasawa N. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12980. doi: 10.1021/ja205186k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kirai N, Iguchi S, Ito T, Takaya J, Iwasawa N. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2013;86:784. 1,1-Diborylalkenes have also been detected as intermediates in a cobalt-catalyzed synthesis of 1,1,1-triborylalkanes from styrenes, see ref 29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Ho HE, Asao N, Yamamoto Y, Jin T. Org Lett. 2014;16:4670. doi: 10.1021/ol502285s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li H, Carroll PJ, Walsh PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:3521. doi: 10.1021/ja077664u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Weber L, Eickhoff D, Halama J, Werner S, Kahlert J, Stammler HG, Neumann B. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2013;2013:2608. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Lee C-I, Shih WC, Zhou J, Reibenspies JH, Ozerov OV. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:14003. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Abu Ali H, Al Quntar AEA, Goldberg I, Srebnik M. Organometallics. 2002;21:4533. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hyodo K, Suetsugu M, Nishihara Y. Org Lett. 2014;16:440. doi: 10.1021/ol403326z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Maderna A, Pritzkow H, Siebert W. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1996;35:1501. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Jiao J, Nakajima K, Nishihara Y. Org Lett. 2013;15:3294. doi: 10.1021/ol401333j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jiao J, Hyodo K, Hu H, Nakajima K, Nishihara Y. J Org Chem. 2014;79:285. doi: 10.1021/jo4024057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matteson DS. Synthesis. 1975;1975:147. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Hata T, Kitagawa H, Masai H, Kurahashi T, Shimizu M, Hiyama T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:790. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010216)40:4<790::aid-anie7900>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kurahashi T, Hata T, Masai H, Kitagawa H, Shimizu M, Hiyama T. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:6381. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Obligacion JV, Neely JM, Yazdani AN, Pappas I, Chirik PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:5855. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.For selected examples of an approach to 1,1-difunctionalization of terminal alkynes that is mechanistically distinct and involves metal vinylidenes, see:; (a) McDonald FE, Schultz CC, Chatterjee AK. Organometallics. 1995;14:3628. [Google Scholar]; (b) McDonald FE, Bowman JL. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:4675. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ohmura T, Yamamoto Y, Miyaura N. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4990. [Google Scholar]; (d) Chen Y, Ho DM, Lee C. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12184. doi: 10.1021/ja053462r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Gunanathan C, Hölscher M, Pan F, Leitner W. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:14349. doi: 10.1021/ja307233p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For reviews on metal vinylidene chemistry, see:; (f) Trost BM, McClory A. Chem - Asian J. 2008;3:164. doi: 10.1002/asia.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Bruneau C, Dixneuf PH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:2176. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Kehr G, Erker G. Chem Commun. 2012;48:1839. doi: 10.1039/c1cc15628d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Suginome M. Chem Rec. 2010;10:348. doi: 10.1002/tcr.201000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen C, Voss T, Fröhlich R, Kehr G, Erker G. Org Lett. 2011;13:62. doi: 10.1021/ol102544x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.For selected examples of syntheses of tiagabine, see:; (a) Bartoli G, Cipolletti R, Di Antonio G, Giovannini R, Lanari S, Marcolini M, Marcantoni E. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:3509. doi: 10.1039/c005042c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Andersen KE, Braestrup C, Groenwald FC, Joergensen AS, Nielsen EB, Sonnewald U, Soerensen PO, Suzdak PD, Knutsen LJS. J Med Chem. 1993;36:1716. doi: 10.1021/jm00064a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Song S, Zhu SF, Pu LY, Zhou QL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:6072. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Endo K, Ohkubo T, Hirokami M, Shibata T. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11033. doi: 10.1021/ja105176v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sun C, Potter B, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:6534. doi: 10.1021/ja500029w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee JCH, McDonald R, Hall DG. Nat Chem. 2011;3:894. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Feng X, Jeon H, Yun J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:3989. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hong K, Liu X, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:10581. doi: 10.1021/ja505455z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Jo W, Kim J, Choi S, Cho SH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:9690. doi: 10.1002/anie.201603329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Joannou MV, Moyer BS, Meek SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:6176. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For a tutorial review, see:; (h) Xu L, Zhang S, Li P. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:8848. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00338e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Shafer TJ, Meyer DA, Crofton KM. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:123. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sakamoto N, Saito S, Hirose T, Suzuki M, Matsuo S, Izumi K, Nagatomi T, Ikegami H, Umeda K, Tsushima K, Matsuo N. Pest Manage Sci. 2004;60:25. doi: 10.1002/ps.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.For selected examples, see:; (a) Keffer JL, Plaza A, Bewley CA. Org Lett. 2009;11:1087. doi: 10.1021/ol802890b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Williamson RT, Singh IP, Gerwick WH. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:7025. [Google Scholar]; (c) Morinaka BI, Skepper CK, Molinski TF. Org Lett. 2007;9:1975. doi: 10.1021/ol0705696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.For selected examples of methods for the conversion of terminal alkynes to carboxylic acids and esters, see:; (a) Zeng M, Herzon SB. J Org Chem. 2015;80:8604. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b01220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kim I, Lee C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:10023. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Zhang L, Huang Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:15600. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Palmer WN, Zarate C, Chirik PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:2589. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b12896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castle RB, Matteson DS. J Organomet Chem. 1969;20:19. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mita T, Ikeda Y, Michigami K, Sato Y. Chem Commun. 2013;49:5601. doi: 10.1039/c3cc42675k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.(a) Baker RT, Nguyen P, Marder TB, Westcott SA. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1995;34:1336. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nguyen P, Coapes RB, Woodward AD, Taylor NJ, Burke JM, Howard JAK, Marder TB. J Organomet Chem. 2002;652:77. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmer WN, Obligacion JV, Pappas I, Chirik PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:766. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmer WN, Diao T, Pappas I, Chirik PJ. ACS Catal. 2015;5:622. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coombs JR, Zhang L, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:16140. doi: 10.1021/ja510081r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.(a) Knijnenburg Q, Gambarotta S, Budzelaar PHM. Dalton Trans. 2006;5442 doi: 10.1039/b612251e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bart SC, Chlopek K, Bill E, Bouwkamp MW, Lobkovsky E, Neese F, Wieghardt K, Chirik PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13901. doi: 10.1021/ja064557b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noguchi H, Hojo K, Suginome M. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:758. doi: 10.1021/ja067975p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.