Abstract

Glioblastoma is the most aggressive malignant brain tumor in humans and is difficult to cure using current treatment options. Hypoxic regions are frequently found in glioblastoma, and increased levels of hypoxia are associated with poor clinical outcomes of glioblastoma patients. Hypoxia plays important roles in the progression and recurrence of glioblastoma because of drug delivery deficiencies and induction of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in tumor cells, which lead to poor prognosis. We focused on a promising hypoxia-targeted internal radiotherapy agent, 64Cu-diacetyl-bis (N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) (64Cu-ATSM), to address the need for additional treatment for glioblastoma. This compound can target the overreduced state under hypoxic conditions within tumors. Clinical positron emission tomography studies using radiolabeled Cu-ATSM have shown that Cu-ATSM accumulates in glioblastoma and its uptake is associated with high hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression. To evaluate the therapeutic potential of this agent for glioblastoma, we examined the efficacy of 64Cu-ATSM in mice bearing U87MG glioblastoma tumors. Administration of single dosage (18.5, 37, 74, 111, and 148 MBq) and multiple dosages (37 MBq × 4) of 64Cu-ATSM was investigated. Single administration of 64Cu-ATSM in high-dose groups dose-dependently inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival, with slight and reverse signs of adverse events. Multiple dosages of 64Cu-ATSM remarkably inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival. By splitting the dose of 64Cu-ATSM, no adverse effects were observed. Our findings indicate that multiple administrations of 64Cu-ATSM have effective antitumor effects in glioblastoma without side effects, indicating its potential for treating this fatal disease.

Introduction

Glioblastoma is the most aggressive malignant brain tumor in humans and is classified as an aggressive grade IV diffuse glioma of astrocytic lineage [1]. Standard therapies are insufficient, and their toxicities lead to severe lifelong morbidity even in rare cases of survival. Extensive hypoxic areas are associated with poor prognosis of glioblastoma patients, as hypoxia promotes the malignant characteristics of cancer cells [2], [3], [4], [5]. Glioblastoma shows rapid cellular growth; the resulting hypercellular regions in glioblastoma become highly hypoxic, which stimulates the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) [6]. HIF-1α expression in glioblastoma promotes angiogenesis by inducing vascular endothelial growth factor. However, new vessels constructed by this process are not well organized, and there are many gaps between endothelial cells. This leads to vascular stasis, resulting in drug delivery deficiency, hypoxia, and induction of malignant behavior in glioblastoma [6]. These factors make it difficult to effectively treat this disease.

Because of the significance of hypoxia in the malignancy and aggressiveness of glioblastoma, targeting hypoxia may improve patient outcomes. Therefore, we focused on 64Cu-diacetyl-bis (N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) (64Cu-ATSM), a promising theranostic agent that targets hypoxic regions in tumor [7], [8], [9]. Cu-ATSM molecules labeled with various Cu radioisotopes, such as 60Cu, 62Cu, and 64Cu, were originally developed as imaging agents targeting hypoxic regions in tumors for use with positron emission tomography (PET) [7], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]. Preclinical studies revealed that Cu-ATSM rapidly diffuses into cells and tissues, even in low-perfusion areas, and becomes trapped within cells under highly reduced conditions such as hypoxia; additionally, tumor uptake of Cu-ATSM is correlated with HIF-1α expression [10], [11], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. In recent years, clinical PET studies using radiolabeled Cu-ATSM have been conducted for many types of cancers worldwide and have shown that Cu-ATSM uptake is associated with therapeutic resistance, metastatic potential, and poor prognosis [12], [18], [19], [20], [21]. A clinical PET study of patients with glioma suggested that Cu-ATSM is a suitable biomarker for predicting highly malignant grades (glioblastoma) and that Cu-ATSM uptake is correlated with high HIF-1α expression [21], suggesting an underlying mechanism for Cu-ATSM uptake in glioblastoma.

64Cu-ATSM can be used not only as a PET imaging agent but also as an internal radiotherapy agent against tumors because 64Cu shows β+ decay (0.653 MeV, 17.4%) as well as β− decay (0.574 MeV, 40%) and electron capture (42.6%). Photons from electron-positron annihilation can be detected by PET, while β− particles and Auger electrons emitted from this nuclide can damage tumor cells [7], [9], [22]. 64Cu-ATSM reduces the clonogenic survival of tumor cells under hypoxia by inducing postmitotic apoptosis [9]. This is caused by heavy damage to DNA via Auger electrons, which have high liner energy transfer (LET) [23]. An in vivo study of hamsters bearing human cancer tumors demonstrated that 64Cu-ATSM treatment increased survival time [7]. These previous studies support the feasibility of 64Cu-ATSM treatment for glioblastoma based on its high permeability and high-LET radiation.

We hypothesized that 64Cu-ATSM is a therapeutic option for glioblastoma and examined the efficacy of single and multiple administration of 64Cu-ATSM using mice with subcutaneous U87MG glioblastoma xenografts.

Materials and Methods

Radioactive Tracers

64Cu was produced, purified, and used to synthesize 64Cu-ATSM as previously described [24], [25]. The radiochemical purity of 64Cu-ATSM was determined by silica gel thin-layer chromatography (silica gel 60; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) with ethyl acetate as the mobile phase. Radioactivity on the thin-layer chromatography plates was analyzed with a bioimaging analyzer (FLA-7000; Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan). The radiochemical purity of 64Cu-ATSM was greater than 95%.

Cell Culture and Animal Model

Human glioblastoma U87MG cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA; May 20, 2009; characterized by short tandem repeats, Y-chromosome, and Q-band assays) and immediately expanded and frozen in our laboratory. Early passage cells, less than the cumulative 2 to 3 months of subculture after receipt, were used for all experiments. Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air.

Six-week-old male BALB/c nude mice (20-25 g body weight) were obtained from Japan SLC (Hamamatsu, Japan). U87MG cells (1 × 107 cells) suspended in phosphate-buffered saline were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of mice. Mice bearing tumors approximately 5 mm in diameter were used for subsequent experiments. All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the National Institutes for Quantum and Radiological Science and Technology (QST, Chiba, Japan) and conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines.

In Vivo Treatment Study

Mice bearing U87MG tumors were randomized into seven groups (n = 7/group). Six groups were intravenously injected with different single doses of 64Cu-ATSM with 18.5, 37, 74, 111, or 148 MBq or saline as a control. One group was intravenously injected on 4 different days (day 0, 7, 21, and 28) with 64Cu-ATSM at a dose of 37 MBq (37 MBq × 4). During the in vivo treatment study, mice were weighed and tumor size was measured using precision calipers twice weekly. Tumor volume was calculated using an equation (tumor volume = length × width2 × π/6), and the tumor volume on each day was determined as the percent of the initial tumor volume on day 0. The initial tumor volume is shown in Supplementary Table S1. Mice were sacrificed when the tumor volume reached a humane endpoint. Survivability was also observed for 80 days, and percentage of survival was calculated.

Measurement of Hematological and Biochemical Parameters

To evaluate side effects, hematological and biochemical parameters were measured using non–tumor-bearing mice that received treatments similar to that in the in vivo treatment study (n = 5/group). Measurements of hematological parameters were performed at the starting point just before 64Cu-ATSM injection (day 0) and days 2, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, and 49 after 64Cu-ATSM injection using blood collected from the tail vein. The concentration of white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets was determined using a hematological analyzer (Celltac MEK-6458, Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan). Biochemical parameters were measured at day 49 after the first 64Cu-ATSM injection using mouse plasma prepared with blood collected from the heart. Levels of glutamate pyruvate transaminase and alkaline phosphatase for liver function as well as urea nitrogen and creatinine for kidney function were measured using a blood biochemical analyzer (Dri-Chem 7000VZ, Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as the means with corresponding standard deviations. P values were calculated using analysis of variance to compare multiple groups. Tumor growth curves were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance. Differences in survival were evaluated using the log-rank test. P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Treatment Response

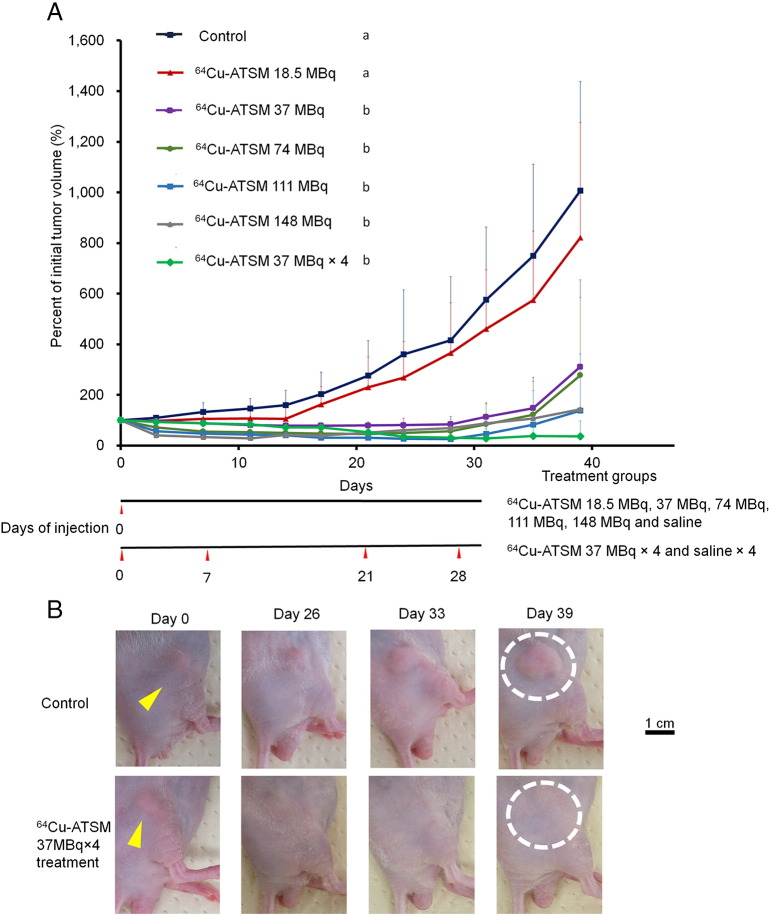

In this study, the efficacy of different single doses of 64Cu-ATSM treatment (18.5, 37, 74, 111, and 148 MBq) and multiple doses of 64Cu-ATSM treatment (37 MBq × 4) against mice bearing glioblastoma U87MG tumors was examined in vivo (n = 7/group). Figure 1A shows the changes in relative tumor volume of each treatment group for 39 days, expressed as a percentage of the initial tumor volume on day 0. Treatment with a single administration of 64Cu-ATSM at 37, 74, 111, and 148 MBq significantly inhibited tumor growth compared to that in the control (P < .05). The ratio of each single treatment group versus the control in an average percentage of initial tumor volume at day 39 was 0.82, 0.31, 0.28, 0.14, and 0.14 at single administration of 64Cu-ATSM of 18.5, 37, 74, 111, and 148 MBq, respectively. These results show that single administration of 64Cu-ATSM had a dose-dependent antitumor effect, showing a plateau at 111 MBq. Single administration of 18.5 MBq 64Cu-ATSM generally inhibited tumor growth compared to that in controls, but the difference was not significant. Four doses of 64Cu-ATSM (37 MBq × 4) showed significantly greater inhibition of tumor growth compared to the control group (P < .05). The ratio of 64Cu-ATSM (37 MBq × 4) versus the control in an average percentage of initial tumor volume at day 39 was 0.04, which was the lowest value among the treatment groups examined in this study. Figure 1B shows the representative tumor appearance on day 0 (before administration), 26, 33, and 39 among the control group and a group treated with multiple doses of 64Cu-ATSM with 37 MBq × 4. Tumors actively grew over time in the control group, while tumors were not visible following multiple doses of 64Cu-ATSM with 37 MBq × 4. In 6 cases among 7 mice in this multiple-dose treatment group, the tumors were nearly invisible on day 39, as shown in Figure 1B.

Figure 1.

Tumor growth in in vivo treatment study with 64Cu-ATSM. (A) Tumor growth curve. Plots of the average percent of initial tumor volume (%) for each treatment group are shown. The following groups were examined: single dose of 64Cu-ATSM with 18.5, 37, 74, 111, or 148 MBq and saline injected on day 0 (n = 7/group), and multiple doses of 64Cu-ATSM with 37 MBq injected on days 0, 7, 21, and 28 (n = 7/group). Treatment schedule is also shown. Values are shown as the mean ± SD. (a, b) Different letters indicate significant differences (P < .05). (B) Tumor appearance in in vivo treatment study with 64Cu-ATSM. Representative tumor appearance is shown on day 0 (before administration), 26, 33, and 39 among the control group (upper) and a group treated with multiple doses of 64Cu-ATSM with 37 MBq × 4 (lower). Yellow arrows indicate the position of subcutaneously bearing tumors on the flanks of the mice. White dots surround the location of tumor presented on day 39. After four treatments with 64Cu-ATSM with 37 MBq, the tumor was not visible on day 39.

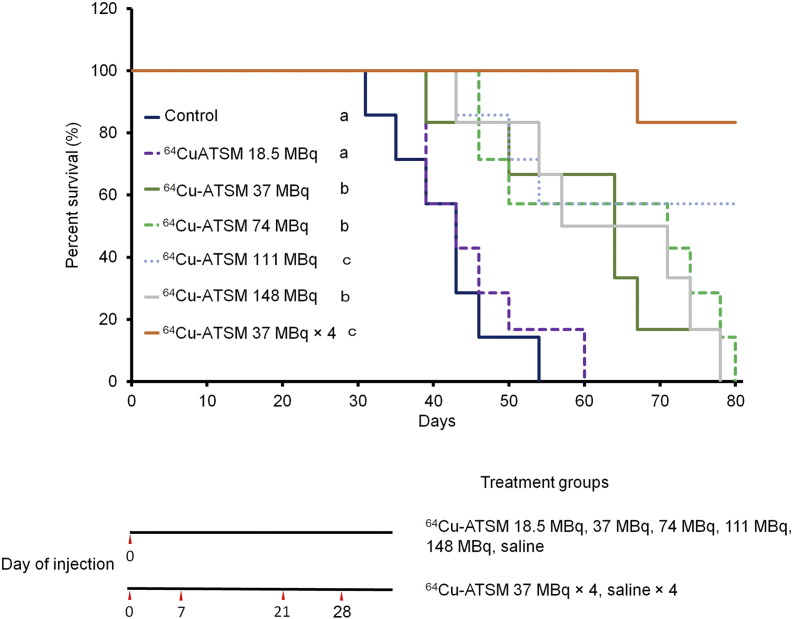

Figure 2 shows the survival curves of each treatment group for 80 days. Survival following single administration of 64Cu-ATSM with 37, 74, 111, and 148 MBq and multiple doses of 64Cu-ATSM with 37 MBq × 4 was greater than that of the control (P < .05). Additionally, both groups that received single administration of 64Cu-ATSM with 111 MBq and multiple doses of 64Cu-ATSM with 37 MBq × 4 showed significantly prolonged survival compared with single administration of 64Cu-ATSM with 18.5, 37, 74, and 148 MBq (P < .05). Among the single-treatment groups, 111 MBq showed the highest effect on survival. Multiple doses of 64Cu-ATSM with 37 MBq × 4 generally resulted in longer survival compared to single administration of 64Cu-ATSM with 111 MBq, but there was no significant difference between the two treatments.

Figure 2.

Survival curves in in vivo treatment study with 64Cu-ATSM. Survival curves for each treatment group are shown. The following groups were examined: single dose of 64Cu-ATSM with 18.5, 37, 74, 111, or 148 MBq and saline injected on day 0 (n = 7/group), and multiple doses of 64Cu-ATSM with 37 MBq on day 0, 7, 21, and 28 (n = 7/group). Treatment schedule is also shown. Values are shown as the mean ± SD. (a, b, c) Different letters indicate significant differences (P < .05).

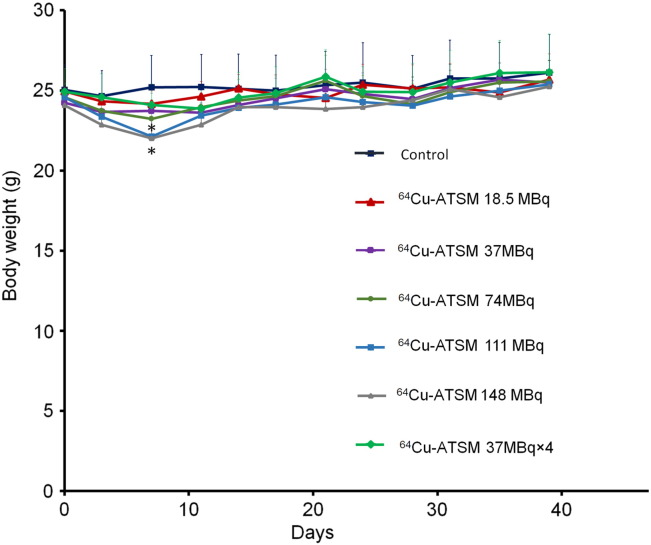

The body weights of each mouse were also measured for 39 days (Figure 3). On day 7, there was a significant reduction in the body weight of mice treated with a single dose of 64Cu-ATSM of 111 and 148 MBq compared to that in the control group (P < .05). The body weight loss was recovered to normal levels by day 14 and remained the same as the control thereafter. No body weight loss was observed after multiple doses of 64Cu-ATSM with 37 MBq × 4.

Figure 3.

Changes in body weights after in vivo treatment with 64Cu-ATSM. Plots of the average body weight for each treatment group in the in vivo treatment study are shown. Values are shown as the mean ± SD. *P > .05 versus control.

Measurement of Hematological and Biochemical Parameters

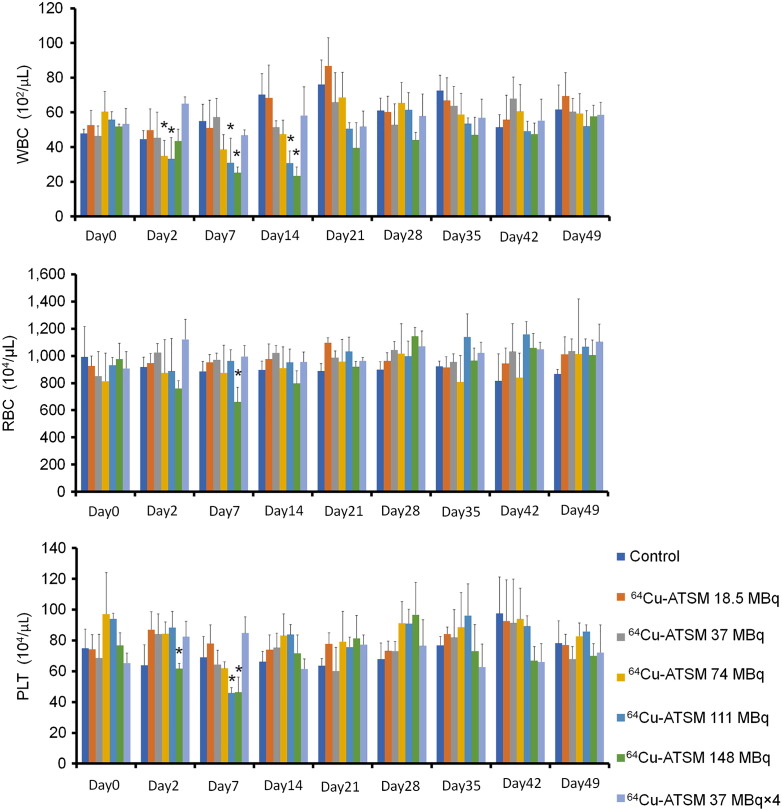

The number of white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets in the blood was examined in non–tumor-bearing mice injected with 64Cu-ATSM in a manner similar to that in the in vivo treatment study (Figure 4). There were significant reductions in the number of white blood cells on day 2 following single injection of 64Cu-ATSM with 74 MBq and 111 MBq, and days 7 and 14 with 111 MBq and 148 MBq, although the values recovered to normal levels by day 21 (P < .05). Only treatment with single administration of 64Cu-ATSM of 148 MBq showed a significant reduction in the number of red blood cells at day 7 (P < .05). There were significant reductions in the number of platelets at days 2 and 7 after administration of 64Cu-ATSM with 148 MBq and only on day 7 with 111 MBq (P < .05). The numbers of both red blood cells and platelets were recovered to normal levels by day 14. The multiple-administration group showed no symptoms of hematological toxicity and maintained a healthy physical appearance throughout the experimental period.

Figure 4.

Hematological toxicity in mice treated with 64Cu-ATSM. Hematological toxicity was examined among each treatment group similar to that in the in vivo treatment analysis with 64Cu-ATSM. Average numbers of white blood cells (WBC), red blood cells (RBC), and platelets (PLT) at day 0 (the starting point before 64Cu-ATSM injection) and at days 2, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, and 49 after first 64Cu-ATSM and saline injection (n = 5/group) are shown. Values are shown as the mean ± SD. *P > .05 versus control at day 0.

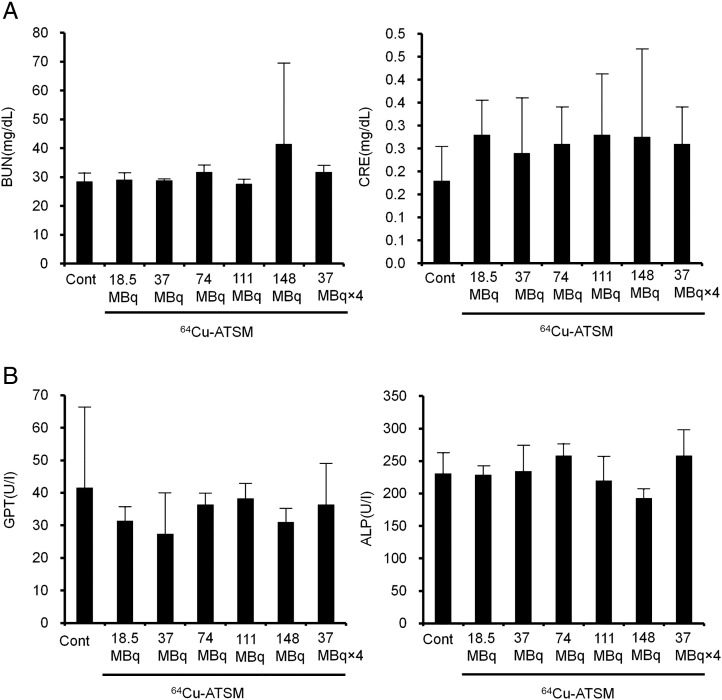

Liver and kidney functions remain unaltered following treatments with both single and multiple administrations of 64Cu-ATSM. There were no significant differences in blood urea nitrogen and creatinine for kidney function and glutamate pyruvate transaminase and alkaline phosphatase for liver function compared to those in the control group on day 49 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Renal and hepatic toxicity in mice treated with 64Cu-ATSM. Renal and hepatic toxicity was examined among each treatment group similar to that in the in vivo treatment analysis with 64Cu-ATSM. Data were measured at day 49 after first 64Cu-ATSM and saline injection (control) (n = 5/group). (A) Levels of urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine (CRE) for kidney function. (B) Levels of glutamate pyruvate transaminase (GPT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) for liver function.

Discussion

This study investigated the therapeutic potential of 64Cu-ATSM for the treatment of glioblastoma. Glioblastoma typically causes hypoxia, and hypoxic areas in glioblastoma are known to be resistant to chemo- and radiation therapy [2], [3], [4], [5]. To target hypoxic areas, we focused on the potential theranostic agent 64Cu-ATSM for targeting the tumor overreduced state under hypoxic conditions [7], [9], [10], [11], [13], [14], [15], [16], [22]. Because Cu-ATSM can predict highly malignant grades of glioblastoma tumors with high HIF-1α expression [21], 64Cu-ATSM may be useful for treating this disease. In this study, we demonstrated that intravenous administration of 64Cu-ATSM was effective for treating mice bearing U87MG glioblastoma. Our findings showed that single administration of 64Cu-ATSM had a dose-dependent therapeutic effect, significantly inhibited tumor growth, and prolonged survival against U87MG glioblastoma. However, slight and reverse hematological toxicity and body weight loss were also observed in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, split dosage of 64Cu-ATSM (37 MBq × 4) showed better antitumor effects for inhibiting tumor growth and prolonging survival in U87MG glioblastoma without significant adverse events. Because there is no effective therapy available for glioblastoma, multiple doses of 64Cu-ATSM may provide a new therapeutic option for this fatal disease with fewer side effects.

In our in vivo treatment study, single administration of 64Cu-ATSM showed dose-dependent inhibition of tumor growth for 39 days, and both 111 and 148 MBq significantly inhibited tumor growth compared to that in controls (P < .05). However, only single administration of 64Cu-ATSM with 111 MBq significantly prolonged survival compared to that in the control (P < .05). Mice treated with a single administration of 64Cu-ATSM with 111 and 148 MBq showed slight body weight loss and reduced white blood cells and platelets. Additionally, toxicity was observed with 148-MBq administration as a reduction in red blood cells. This additional toxicity may lead to poor survival following single-dose treatment with 148 MBq of 64Cu-ATSM. To maintain the therapeutic potential of 64Cu-ATSM with fewer or less severe adverse events, we administered four doses of 64Cu-ATSM (37 MBq × 4) and found significant inhibition of tumor growth and prolonged survival compared to that in controls. In addition, treatment with multiple doses of 64Cu-ATSM (37 MBq × 4) did not result in body weight loss or hematological or hepatorenal toxicity. Therefore, our data suggest that multiple doses of 64Cu-ATSM effectively inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival against glioblastoma tumors as well as reduced the adverse effects of 64Cu-ATSM therapy.

Glioblastoma is typically accompanied by malfunctions in the vasculature, which lead to hypoxia [6]. In this study, we used a U87MG mouse model with high HIF-1α expression caused by hypoxia [26], [27]. Hypoxic environments in glioblastoma tissues induce HIF-1α, leading to tumor malignant behaviors, such as regrowth and metastasis [28], [29], [30]. Clinical PET investigations have indicated that 64Cu-ATSM accumulates in highly malignant grade glioblastoma showing high HIF-1α expression [21]. 64Cu-ATSM can target hypoxic regions in tumor tissues even when blood perfusion is limited [11], [13], [31], [32], [33]. β− particles and Auger electrons emitted by 64Cu can damage tumor cells [7], [9], [22]. Particularly, high-LET Auger electrons cause severe damage to DNA and induce postmitotic apoptosis in tumor cells [9], [23]. These unique features of 64Cu-ATSM may contribute to its effectiveness for treating glioblastoma.

Our in vivo treatment study showed that multiple administrations of 64Cu-ATSM (37 MBq × 4) had a therapeutic effect against glioblastoma without significant adverse events. In previous studies, we estimated the human dosimetry of 64Cu-ATSM based on biodistribution data in normal organs of mice [24], [34]. The liver, red marrow, and ovaries were demonstrated to be dose-limiting organs in 64Cu-ATSM therapy, and the estimated radiation doses to those organs in humans at the therapeutic dosage of 64Cu-ATSM calculated from 37 MBq per mouse were low compared to the reported tolerance doses [24], [34]. Thus, 64Cu-ATSM therapy may be applied in humans; however, the therapeutic effect and toxicity for multiple administrations of 64Cu-ATSM should be carefully considered in human studies. Additionally, PET imaging for 64Cu-ATSM may be useful for monitoring dosimetry in tumors and organs during 64Cu-ATSM therapy for individual patients.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that multiple administrations of 64Cu-ATSM effectively inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival without significant adverse events in mice bearing U87MG tumors. These findings indicate that multiple doses of 64Cu-ATSM therapy provide a new therapeutic option for glioblastoma, which is difficult to cure using current treatment options in clinical practice.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Initial Tumor Volume in the In Vivo Study

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mr. Hisashi Suzuki (QST) for providing the radiopharmaceuticals. This study was supported by the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research and Project for Cancer Research and Therapeutic Evolution (P-CREATE) of the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED).

References

- 1.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, Scheithauer BW, Kleihues P. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsieh CH, Shyu WC, Chiang CY, Kuo JW, Shen WC, Liu RS. NADPH oxidase subunit 4-mediated reactive oxygen species contribute to cycling hypoxia-promoted tumor progression in glioblastoma multiforme. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rong Y, Durden DL, Van Meir EG, Brat DJ. 'Pseudopalisading' necrosis in glioblastoma: a familiar morphologic feature that links vascular pathology, hypoxia, and angiogenesis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:529–539. doi: 10.1097/00005072-200606000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merighi S, Benini A, Mirandola P, Gessi S, Varani K, Leung E, Maclennan S, Borea PA. Adenosine modulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression via hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in human glioblastoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez-Lazaro M. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 as a possible target for cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2332–2335. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang WJ, Chen WW, Zhang X. Glioblastoma multiforme: effect of hypoxia and hypoxia inducible factors on therapeutic approaches. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:2283–2288. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis J, Laforest R, Buettner T, Song S, Fujibayashi Y, Connett J, Welch M. Copper-64-diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone): an agent for radiotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1206–1211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis JS, McCarthy DW, McCarthy TJ, Fujibayashi Y, Welch MJ. Evaluation of 64Cu-ATSM in vitro and in vivo in a hypoxic tumor model. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:177–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obata A, Kasamatsu S, Lewis JS, Furukawa T, Takamatsu S, Toyohara J, Asai T, Welch MJ, Adams SG, Saji H. Basic characterization of 64Cu-ATSM as a radiotherapy agent. Nucl Med Biol. 2005;32:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujibayashi Y, Cutler CS, Anderson CJ, McCarthy DW, Jones LA, Sharp T, Yonekura Y, Welch MJ. Comparative studies of Cu-64-ATSM and C-11-acetate in an acute myocardial infarction model: ex vivo imaging of hypoxia in rats. Nucl Med Biol. 1999;26:117–121. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(98)00049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujibayashi Y, Taniuchi H, Yonekura Y, Ohtani H, Konishi J, Yokoyama A. Copper-62-ATSM: a new hypoxia imaging agent with high membrane permeability and low redox potential. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1155–1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW, Lewis JS, Laforest R, Siegel BA, Welch MJ. Assessing tumor hypoxia in cervical cancer by PET with 60Cu-labeled diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) J Nucl Med. 2008;49:201–205. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.048520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obata A, Yoshimi E, Waki A, Lewis JS, Oyama N, Welch MJ, Saji H, Yonekura Y, Fujibayashi Y. Retention mechanism of hypoxia selective nuclear imaging/radiotherapeutic agent cu-diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) (Cu-ATSM) in tumor cells. Ann Nucl Med. 2001;15:499–504. doi: 10.1007/BF02988502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holland JP, Giansiracusa JH, Bell SG, Wong LL, Dilworth JR. In vitro kinetic studies on the mechanism of oxygen-dependent cellular uptake of copper radiopharmaceuticals. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:2103–2119. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/7/017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshii Y, Yoneda M, Ikawa M, Furukawa T, Kiyono Y, Mori T, Yoshii H, Oyama N, Okazawa H, Saga T. Radiolabeled Cu-ATSM as a novel indicator of overreduced intracellular state due to mitochondrial dysfunction: studies with mitochondrial DNA-less rho0 cells and cybrids carrying MELAS mitochondrial DNA mutation. Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowen SR, van der Kogel AJ, Nordsmark M, Bentzen SM, Jeraj R. Characterization of positron emission tomography hypoxia tracer uptake and tissue oxygenation via electrochemical modeling. Nucl Med Biol. 2011;38:771–780. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joergensen JT, Madsen J, Kjaer A. PET imaging of hypoxia with 64Cu-ATSM in human ovarian cancer: comparison of xenografts in mice and rats. Cancer Res. 2011;71(8 Suppl):5308. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dietz DW, Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW, Malyapa RS, Myerson RJ, Picus J, Ritter J, Lewis JS, Welch MJ, Siegel BA. Tumor hypoxia detected by positron emission tomography with 60Cu-ATSM as a predictor of response and survival in patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal carcinoma: a pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1641–1648. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9420-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis JS, Laforest R, Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW, Welch MJ, Siegel BA. An imaging comparison of 64Cu-ATSM and 60Cu-ATSM in cancer of the uterine cervix. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1177–1182. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.051326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato Y, Tsujikawa T, Oh M, Mori T, Kiyono Y, Fujieda S, Kimura H, Okazawa H. Assessing tumor hypoxia in head and neck cancer by PET with 62Cu-diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39:1027–1032. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tateishi K, Tateishi U, Sato M, Yamanaka S, Kanno H, Murata H, Inoue T, Kawahara N. Application of 62Cu-diacetyl-bis (N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) PET imaging to predict highly malignant tumor grades and hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha expression in patients with glioma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:92–99. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshii Y, Furukawa T, Kiyono Y, Watanabe R, Mori T, Yoshii H, Asai T, Okazawa H, Welch MJ, Fujibayashi Y. Internal radiotherapy with copper-64-diacetyl-bis (N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) reduces CD133+ highly tumorigenic cells and metastatic ability of mouse colon carcinoma. Nucl Med Biol. 2011;38:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McMillan DD, Maeda J, Bell JJ, Genet MD, Phoonswadi G, Mann KA, Kraft SL, Kitamura H, Fujimori A, Yoshii Y. Validation of 64Cu-ATSM damaging DNA via high-LET Auger electron emission. J Radiat Res. 2015;56:784–791. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rrv042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshii Y, Furukawa T, Matsumoto H, Yoshimoto M, Kiyono Y, Zhang MR, Fujibayashi Y, Saga T. Cu-ATSM therapy targets regions with activated DNA repair and enrichment of CD133 cells in an HT-29 tumor model: sensitization with a nucleic acid antimetabolite. Cancer Lett. 2016;376:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohya T, Nagatsu K, Suzuki H, Fukada M, Minegishi K, Hanyu M, Fukumura T, Zhang MR. Efficient preparation of high-quality 64Cu for routine use. Nucl Med Biol. 2016;43:685–691. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agrawal R, Pandey P, Jha P, Dwivedi V, Sarkar C, Kulshreshtha R. Hypoxic signature of microRNAs in glioblastoma: insights from small RNA deep sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:686. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong CG, Wu WK, Feng SY, Yu J, Shao JF, He GM. Suppressing the malignant phenotypes of glioma cells by lentiviral delivery of small hairpin RNA targeting hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:2323–2332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen RL. Brain tumor hypoxia: tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, imaging, pseudoprogression, and as a therapeutic target. J Neurooncol. 2009;92:317–335. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9827-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flamme I, Krieg M, Plate KH. Up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in stromal cells of hemangioblastomas is correlated with up-regulation of the transcription factor HRF/HIF-2alpha. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:25–29. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65541-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliver L, Olivier C, Marhuenda FB, Campone M, Vallette FM. Hypoxia and the malignant glioma microenvironment: regulation and implications for therapy. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2009;2:263–284. doi: 10.2174/1874467210902030263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oh M, Tanaka T, Kobayashi M, Furukawa T, Mori T, Kudo T, Fujieda S, Fujibayashi Y. Radio-copper-labeled Cu-ATSM: an indicator of quiescent but clonogenic cells under mild hypoxia in a Lewis lung carcinoma model. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka T, Furukawa T, Fujieda S, Kasamatsu S, Yonekura Y, Fujibayashi Y. Double-tracer autoradiography with Cu-ATSM/FDG and immunohistochemical interpretation in four different mouse implanted tumor models. Nucl Med Biol. 2006;33:743–750. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dearling JL, Lewis JS, Mullen GE, Welch MJ, Blower PJ. Copper bis(thiosemicarbazone) complexes as hypoxia imaging agents: structure-activity relationships. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2002;7:249–259. doi: 10.1007/s007750100291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshii Y, Matsumoto H, Yoshimoto M, Furukawa T, Morokoshi Y, Sogawa C, Zhang MR, Wakizaka H, Yoshii H, Fujibayashi Y. Controlled administration of penicillamine reduces radiation exposure in critical organs during 64Cu-ATSM internal radiotherapy: a novel strategy for liver protection. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Initial Tumor Volume in the In Vivo Study