Abstract

Purpose

The aims of this study are to establish a time point to determine the most beneficial time to administer GCEE post incident to reduce oxidative damage and second, by using redox proteomics, to determine if GCEE can readily suppress 3-NT modification in TBI animals.

Experimental design

By using a moderate traumatic brain injury model with Wistar rats, it is hypothesized that the role of 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) formation as an intermediate will predict the involvement of protein nitration/nitrosation and oxidative damage in the brain.

Results

In this experiment, the levels of protein carbonyls, 4-hydroxynonenal, and 3-nitrotyrosine were significantly elevated in TBI injured, saline treated rats compared with those who sustained an injury and were treated with 150 mg/kg of the glutathione mimetic, GCEE.

Conclusion and clinical relevance

Determining the existence of elevated 3-NT levels provides insight into the relationship between the protein nitration/nitrosation and the oxidative damage, which can determine the pathogenesis and progression of specific neurological diseases.

Keywords: 3-Nitrotyrosine (3–NT), Protein nitration, Traumatic brain injury (TBI), Reactive nitrogen species (RNS), Nitrosative stress

1 Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) can be defined as a spontaneous injury in which the brain is affected through sudden trauma to the head or direct exposure or injury to brain tissue. There are an estimated 10 million cases annually worldwide with approximately 20% occurring in the United States [1]. There are three classifications of TBI: mild, moderate, and severe. The majority of traumatic brain injuries are considered mild, however there is a strong correlation between the incidence of death and TBI severity as approximately 1% of mild, 15% of moderate, and 40% of severe TBI patients succumb as a result of their injuries [2]. Outcomes can span from complete patient recovery to permanent memory loss and neurological decline.

Traumatic brain injury consists of two stages: primary and secondary injuries. At the moment of injury, the external physical impact on the brain generates primary injury, such as swelling and shearing of neurons as well as changes in cellular pathways. Subsequently, primary injury initiates secondary injury, such as blood brain barrier (BBB) disruption, excitotoxicity, and overproduction of free radicals, resulting in oxidative stress [3, 4]. These radical species, which include reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), can alter protein function. An imbalance of oxidants and antioxidants results in oxidative stress, in the same way, an imbalance of RNS to antioxidants results in nitrosative stress. Upon oxidation or protein nitration, the native conformation and function of proteins and lipids are lost. Elevated levels of •OH and •O2, both reactive oxygen species, have been observed in early TBI models [5, 6] and their elevation in brain after TBI leads to BBB and lipid disruption in rats [7]. As a result, lipid peroxidation occurs and acrolein, malondialdehyde, and 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) are produced. These aldehydes are frequently used as indicators of lipid peroxidation in experimental TBI models to measure levels of oxidative damage.

Peroxynitrite is a potent nitrating agent highly involved in nitrosative stress. Peroxynitrite derived radicals can lead to cellular damage in DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids [8, 9]. Increased oxidative damage in the form of elevated levels of protein nitration/nitrosation was observed in a diffuse, closed head injury mouse model [10]. Protein nitration/nitrosation also inactivates several key mitochondrial enzymes including creatine kinase [11], succinate dehydrogenase [12], and Mn-SOD [13], which has a profound effect on energy metabolism dysregulation, a consequence of traumatic brain injury.

Glutathione, a tripeptide composed of glutamate, cysteine, and glycine, is an important component of antioxidant defense, as it behaves as both a substrate for glutathione peroxidase in the removal of H2O2 and as a free radical scavenger. Strategies to increase glutathione levels have been investigated, as the administration of crude glutathione has been deemed ineffective [14]. Much of the research investigating the upregulation of glutathione has been aimed at providing cysteine to the cell, as it is the limiting reagent in glutathione biosynthesis [15]. GCEE, an analog compound of γ-glutamylcysteine with an ethyl ester moiety, has been shown to be neuroprotective against protein nitration/nitrosation and oxidative stress through glutathione elevation showing its promise as a potential post-injury therapeutic [15-17].

Currently, there is no known cure for traumatic brain injury; however, immediate medical attention after injury is most beneficial for patient recovery. Therefore, therapeutic strategies that improve outcomes following injury are paramount. Several therapeutic strategies including pro-inflammatory inhibitors [18], mitochondrial uncouplers [19], lipid peroxide scavengers [20], hypothermia [21,22], and most recently deep brain stimulation [23] have shown promise as TBI therapies. Researchers have focused on the development of treatment strategies for secondary injuries, such as oxidative and nitrosative stress. The use of redox proteomics has been used to investigate the oxidative modification of proteins that may lead to reduced cognition observed in TBI patients. There is limited research devoted to nitrosative stress, proteomics, and moderate TBI, therefore this work provides insight into the role of antioxidant-based TBI therapies and oxidative damage.

2 Materials and methods

All chemicals were of the highest quality and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise mentioned. GCEE was purchased from Bachem (Torrance, CA, USA).

All surgical, injury, and animal care protocols described below have been approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and are consistent with the animal care procedures set forth in the guidelines of the U.S. Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Thirty Wistar adult male rats (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA) 300—350 g were used in this study. The rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (3.0%), shaved, and then placed in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). Surgery was completed by our collaborator and conducted in the same fashion as previously described by Sullivan [24]. A 1.5 mm injury was used to produce a moderate TBI in each rat except sham animals. Each group (sham, TBI, and GCEE) consisted of six animals. After surgery and injury, a 4 mm disk made from dental cement was placed over the craniotomy site and adhered to the skull using cyanoacrylate. In order to prevent immediate hypothermia, following skin suturing, rats were placed on a warm mat until they regained consciousness (increased attention and mobility). Six rats were given GCEE (150 mg/kg in 300ul of vehicle) i.p. approximately 30 min post injury, while six were given GCEE 60 min after injury. Likewise, six injured rats were given an identical volume of vehicle (saline) 30 min after injury and six were given saline 60 min post injury. The remaining six rats were treated as sham controls, in which they received a craniotomy but not cortical contusion. All rats were kept alive 24 h post injury and then sacrificed. Upon sacrifice, rats were decapitated and the whole brain was rapidly removed, labeled, and placed in a −80°C freezer until use. Cortex tissue from the ipsilateral side was minced and homogenized in 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) containing 137 mM NaCl, 4.6 mM KCl, 1.1 mM KH2PO4, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.6 mM MgSO4 as well as proteinase inhibitors: leupeptin (0.5 mg/mL), pepstatin (0.7 μg/mL), type II S soybean trypsin inhibitor (0.5 μg/mL), and PMSF (40 μg/mL). Brain homogenates were centrifuged at 14 000 × g for 10 min and used for the reminder of the experiments. Protein concentration in the supernatant was determined by the BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

Measurement of markers of oxidative parameters and 2D gel electrophoresis protocols were performed in the same fashion as Reed [16]. In-gel digestion on selected gel spots was performed according to techniques established by Thong-boonkerd [25]. The significant protein spots were excised from SYPRO Ruby stained 2D gels with a clean blade and transferred into clean microcentrifuge tubes. The protein spots were then washed with 0.1M ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) at room temperature for 15 min. Acetonitrile(Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the gel pieces and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The solvent was removed and the gel pieces were dried in a flow hood. The protein spots were incubated with 20 μL of 20 mM DTT (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) in 0.1M NH4HCO3 at 56°C for 45 min. The DTT solution was then removed and replaced with 20 μL of 55 mM iodoacetamide (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) in 0.1M NH4HCO3. The solution was incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. Excess iodoacetamide was removed and replaced with 0.2 mL of 50 mM NH4HCO3 and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Two hundred microliters (200 μL) of acetonitrile was added. After 15 min incubation, the solvent was removed, and the gel spots dried for 30 min in a flow hood. The gel pieces were rehydrated with 20 ng/μL modified trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) in 50 mM NH4HCO3 with the minimal volume to cover the gel pieces. The gel pieces were chopped into smaller peptides and incubated with shaking overnight at 37°C.

A Q Exactive Hybrid Quadrupole – Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham MA) was used to generate peptide mass fingerprints. Peptides resulting from ingel digestion with trypsin were analyzed using liquid chromatography following by mass spectroscopy. Briefly, 2 μL of digestate was run on a Thermo Scientific Easy nano-liquid chromatograph (Thermo Scientific, Waltham MA) at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. A liquid chromatograph was run on a gradient for 95 min. Mass spectrometry was performed on a Thermo Q Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Reported spectra were run in “full ms/collision induced dissociation mode” mode with a range of m/z 350 to 1800, a mass resolution of 70 000, and an ion accumulation time of 250 ms. All mass spectra reported were acquired at the University of Pittsburgh by Christina King and Dr. Renã Robinson. Results from LC/MS/MS spectra used for protein identification from tryptic fragments were searched against the NCBI database using Proteome Discoverer 1.4 software. The search parameters were as followed using the Sequest algorithm and Rattus norvegicus database on July 9, 2015. Maximum trypsin mis-cleavages (2), precursor mass tolerance: (8 ppm), fragment mass tolerance (0.6 Da), static modification: carbamidomethyl/+57.021 Da (Cys), dynamic modification: oxidation/+15.995 Da (Met), peptide confidence level (medium or high), peptide rank (1), and peptide deviation (10 ppm).

Probability-based MOWSE scores were estimated by the comparison of search results against estimated random match population and were reported as −10* Log10 (p), where p is the probability that the protein identification is not correct. For overall levels of protein nitration, p-values were determined by using a two-way ANOVA. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All protein identifications were in the expected size and pI ranges based on their gel position.

3 Results

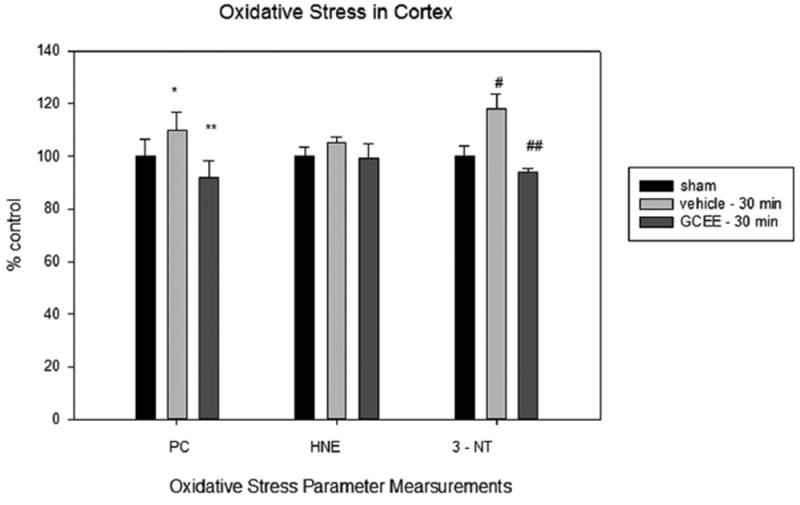

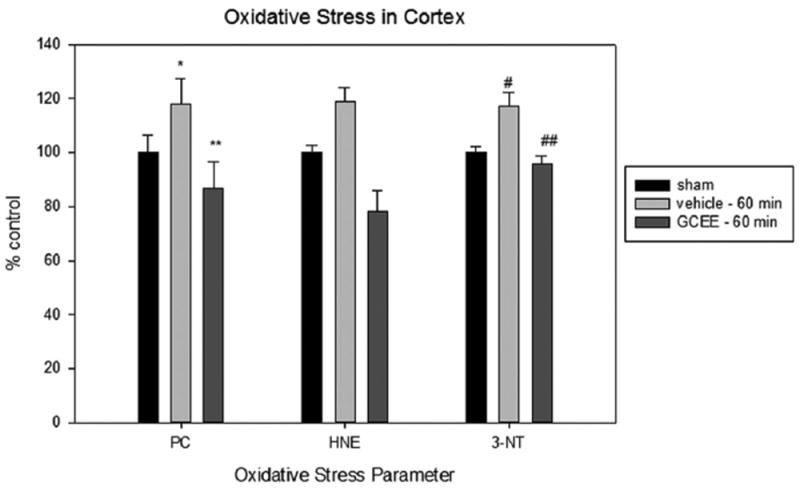

Our findings showed that levels of protein carbonyls were significantly reduced 30 min post injury in animals treated with GCEE undergoing a moderate TBI compared to sham (*p<0.03). There is a greater decrease in this level at 60 min, supporting the notion that GCEE may prevent oxidative damage up to 60 min post injury (Figs. 1 and 2). Although levels of 4-hydroxynonenal were decreased in TBI animals at 30 and 60 min after injury, the reduction was not statistically significant (Figs. 1 and 2). This result is supported by previous data showing that GCEE did not significantly reduce levels of HNE 10 min post injury [16]. Additionally, others have shown that 4-HNE levels do not peak until 48–72 h post TBI via controlled cortical impact [26]. There was a significant increase (20%) in protein nitration observed in TBI rats compared to sham animals at both 30 and 60 min post TBI. GCEE treatment administered 30 min post injury provided protection against protein nitration to a level comparable to control 24 h after treatment. Protein nitration levels are significantly lowered 30 min post injury and are returned to control levels 60 min after moderate TBI (Figs. 1 and 2). This shows that GCEE is protective against moderate TBI in Wistar rats up to 60 min. This reduction of oxidative damage could potentially result in an overall decrease of TBI progression and a plausible increase in cognitive function.

Figure 1.

Levels of protein carbonyls, HNE, and 3-nitrotyrosine in traumatically brain injured rats given vehicle or GCEE 30 post injury. % ±SEM. N = 6 *p<0.05, #p<0.009 compared to sham, **p<0.03, ##p<0.0007 compared to vehicle.

Figure 2.

Levels of protein carbonyls, HNE, and 3-nitrotyrosine in traumatically brain injured rats given vehicle or GCEE 60 post injury. % ±SEM. N = 6 *p<0.05, #p<0.005, compared to sham, **p<0.02, ##p<0.0003 compared to vehicle.

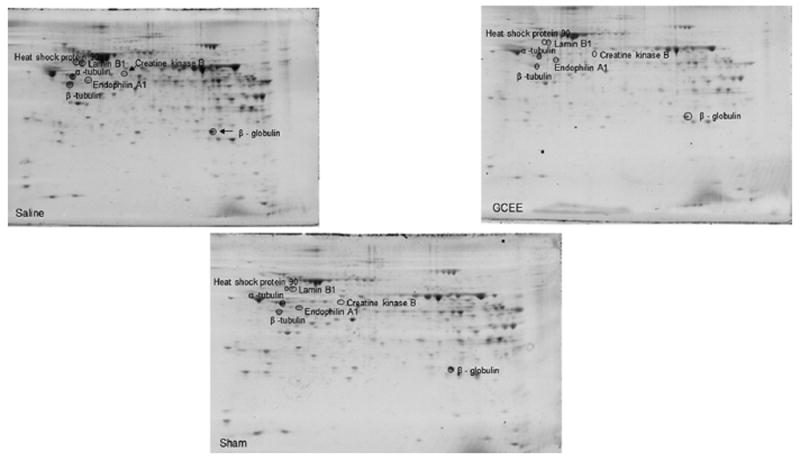

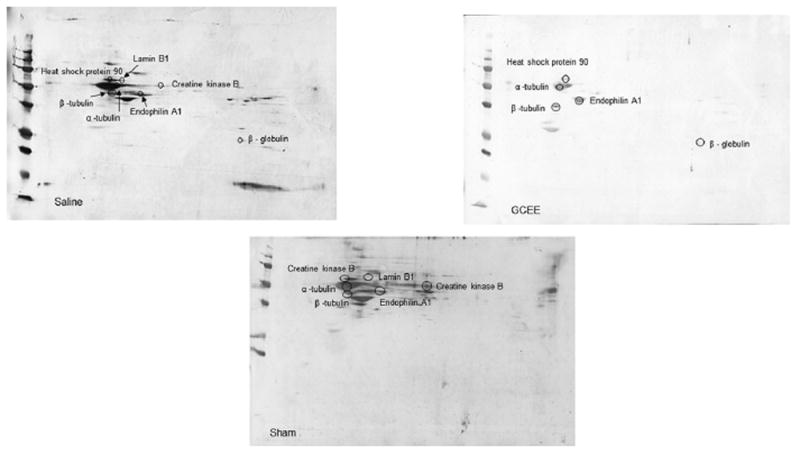

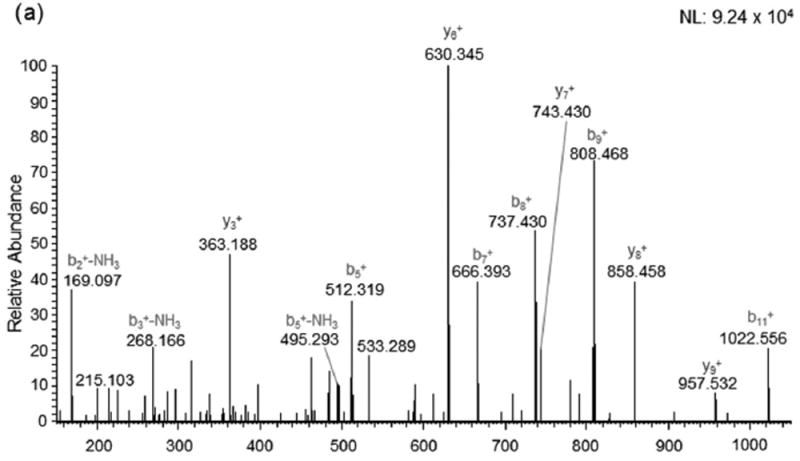

Seven proteins were found to be excessively nitrated in TBI treated rats but no longer altered post-GCEE treatment. These proteins include: β-tubulin, α-tubulin, endophilin A, heat shock protein 90, lamin B1, creatine kinase B, and β-globulin (Table 1). These proteins are highly involved in cytoskeletal integrity, stress response, transcriptional regulation, energy metabolism, and lipid transport, all of which have been found to be reduced in traumatic brain injury [27-30]. 2D gel electrophoresis was performed for sham, TBI plus vehicle, and TBI rats treated with GCEE at different time points following TBI (Fig. 3). 2D Western blots probed with anti-3-nitrotyrosine to detect 3–NT immunoreactivity are shown in Fig. 4 for the different treatment groups. There was a significant increase in protein nitration in brain from TBI rats compared with samples administered GCEE. There appears to be a significant lowering of protein nitration/nitrosation in GCEE treated TBI rats compared with the saline-treated rats in the immunoblots (Fig. 4). This indicates that GCEE appears to have high potential as a post-therapeutic strategy for TBI. Many of these proteins have been identified as being oxidatively modified in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease further bolstering the link between energy metabolism, structural integrity, brain injury, and neurodegeneration [31-33]. A representative mass spectrum for alpha tubulin can be observed in Fig. 5.

Table 1.

Nitrated proteins in found in moderately TBI treated rats

| Protein | MOWSE score | pI | Apparent MW based on migration rate (kDa) | Peptide coverage (%) | Protein nitration (% control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β -tubulin | 60.45 | 4.89 | 49.6 | 25.00 | 122.5 ±54.2 |

| α -tubulin | 9.76 | 5.10 | 49.9 | 12.92 | 54.03 ±8.9 |

| Endophilin A1 | 4.89 | 5.14 | 38.3 | 7.10 | 161.4 ±13.4 |

| Heat shock protein 90 | 15.37 | 5.03 | 83.2 | 9.25 | 728.6 ±27.4 |

| Lamin B1 | 3.92 | 5.16 | 66.6 | 3.75 | 280.8 ±28.6 |

| Creatine kinase B | 6.72 | 5.67 | 42.7 | 8.92 | 164.2 ±49.5 |

| β -globulin | 2.53 | 7.30 | 15.9 | 5.48 | 365.2 ±23.1 |

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional gel comparison of sham, vehicle treated TBI rats, and GCEE treated TBI-treated rats.

Figure 4.

Representative Western blots for sham, vehicle treated TBI rats, and GCEE treated TBI-treated rats.

Figure 5.

Mass spectrum for the protein, alpha tubulin.

4 Discussion

Sudden brain trauma is described as a traumatic brain injury. There is no known cure for TBI; however immediate medical care after injury is most advantageous for patient recovery. ROS production occurs in TBI as observed by increased protein nitration/nitrosation and protein carbonyls [8, 34] and is alleviated by GCEE treatment. In this work, seven proteins were identified by redox proteomics analysis as excessively nitrated in TBI whose functions include energy metabolism, cytoskeletal integrity, and chaperone ability.

Microtubules, composed of alternating α- and β-tubulin, are structures whose main function is maintaining cytoskeletal integrity and axonal transport. In both mild and moderate TBI, the cytoskeleton is altered [35]. If both proteins are nitrated, microtubule assembly will be negatively affected. Autophagy, an ROS process in which protein turnover and degradation is balanced, has been linked to tubulin dysfunction and associated with TBI [36]. GCEE has been shown to reduce autophagy in TBI mice 24 h after treatment, bolstering the ability of GCEE to remediate the consequences of traumatic brain injury [37].

Endophilin is a membrane binding protein with curvature generating and sensing properties that participates in clathrin-dependent endocytosis of synaptic vesicle membranes. It also binds the GTPase dynamin and the phosphoinositide phosphatase, synaptophysin. The absence of endophilin impairs but does not abolish synaptic transmission and results in perinatal lethality, whereas partial endophilin absence causes severe neurological defects, including epilepsy and neurodegeneration. Nitration of this protein supports the literature as the phosphoinositide pathway is impaired in moderate TBI [38]. This disruption of cell signaling can result in poor neurotransmission and signal transduction.

The main function of heat shock proteins is to act as chaperone proteins by repairing misfolded proteins and also assisting in stress response. Heat shock proteins are involved in combating stress by protecting proteins from denaturation [39]. Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) dysfunction may exacerbate protein misfolding, protein aggregation, and reduced effective proteasomal activity. This work correlates with the literature showing that heat shock proteins are altered in TBI bolstering the importance of functioning heat shock proteins in the cell [40].

Lamin B1 is an intermediate filament that provides structural integrity and transcriptional regulation in the nucleus. Nuclear lamins are involved in disassembling and reforming the nuclear envelope during cellular mitosis. Dysfunction of lamin B1 results in DNA damage and neurodegeneration in neurodegenerative disease and myelin degeneration [41, 42].

Creatine kinase, used as an energy transport shuttle system, provides rapid ATP buffering capacity serving as an energy reservoir throughout the cell. This protein has been found to be oxidatively modified in mild TBI [43] and severely impedes ATP production. Although creatine kinase is considered inappropriate as a precise measure of injury severity, possible upregulation could provide important information on TBI, allowing for incidence of injury and GCEE efficacy to be assessed [44]. Thought of as a biomarker for TBI in human CSF from elderly persons [45] and military populations [43] as well as serum patient samples [44], creatine kinase could potentially serve as a low-level biomarker for TBI.

Globulin proteins are major components of blood. Beta globulins are plasma proteins that function in transport of cholesterol, iron (transferrin), and copper (ceruloplasmin). As APOE4 is associated with cholesterol distribution and transport, this allele is a risk factor of Alzheimer disease. Specifically, researchers have identified β-globulin as a potential biomarker of TBI outcome in the APOE mouse model of TBI [46]. This protein has been shown to produce an inflammatory response that weakens the blood-brain barrier and is elevated in the brain 3 months after injury. Functional remediation by GCEE could cause an increase in lipid transport, which would repair cholesterol distribution and reduce inflammation that are consequences of TBI [47].

5 Conclusion

TBI is observed as a sudden brain trauma followed by the increased protein nitration/nitrosation and oxidative damage. Ideally, TBI would be treated preemptively. However, since TBI is sudden and requires immediate medical care after injury, post-therapeutic strategies are being developing to both treat TBI and minimize the time in-between injury and treatment. GCEE, an ester moiety of the dipeptide gamma-glutamylcysteine, is a vital antioxidant that can easily cross the plasma membrane and upregulate GSH in the brain [15]. GCEE prevents oxidative stress induced by amyloid-β peptide and other moieties by scavenging free radicals [48]. GCEE reduced levels of protein carbonyls and 3-NT significantly (Figs. 1 and 2). This study suggests that the elevation of GSH by GCEE up to 60 min post TBI is neuroprotective against oxidative damage associated with moderate TBI. This is one of the first studies to demonstrate a potential postinjury therapeutic strategy for the treatment of TBI. Specific proteins are protected against nitrosative stress associated with TBI, which conceivably modulates loss of function of the proteins in TBI. This is a unique feature of this work as GCEE appears to significantly lower protein nitration/nitrosation in TBI rats, leading to possible promise as a potential post-injury therapeutic strategy for traumatic brain injury.

Clinical Relevance.

As traumatic brain injury is the leading cause of death and disability for persons under the age of 45, providing insight into the field of post-therapeutic strategies is paramount. The rates of TBI are increasing in military populations as the number of traumatic brain injuries is on the rise. Similarly, the incidence of sports related head trauma (i.e. concussions and subsequent memory loss) has led to a decline in youth participation in sports. Oxidative stress has been linked to TBI as TBI is a risk factor for various neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer disease. As there are no treatments for TBI, this work provides valuable insight into the field as it evaluates a time course approach to treating moderate traumatic brain injury using a glutathione mimetic, gamma glutamyl ethyl ester. This compound significantly reduced levels of protein carbonyls, 4-hydroxynonenal, and 3-nitrotyrosine, all markers of oxidative damage. Redox proteomics was used to identify excessively nitrated proteins in moderate TBI, which could serve as potential biomarkers and be used as a diagnostic tool for traumatic brain injury.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant (1R15NS072870-01A1).

Abbreviations

- 3–NT

3-nitrotyrosine

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- CCI

controlled cortical impact

- GCEE

gamma glutamyl ethyl ester

- HNE

4-hydroxynonenal

- PC

protein carbonyls

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

Footnotes

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lucke-Wold BP, Turner RC, Logsdon AF, Bailes JE, et al. Linking traumatic brain injury to chronic traumatic encephalopathy: identification of potential mechanisms leading to neurofibrillary tangle development. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31:1129–1138. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spitz G, Downing MG, McKenzie D, Ponsford JL. Mortality following traumatic brain injury inpatient rehabilitation. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32:1272–1280. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giza CC, Hovda DA. the neurometabolic cascade of concussion. J Athl Train. 2001;36:228–235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barkhoudarian G, Hovda DA, Giza CC. The molecular pathophysiology of concussive brain injury. Clin Sports Med. 2011;30:33–48. vii–iii. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall ED, Braughler JM. Free radicals in CNS injury. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;71:81–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kontos HA, Wei EP. Superoxide production in experimental brain injury. J Neurosurg. 1986;64:803–807. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.64.5.0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith SL, Andrus PK, Zhang JR, Hall ED. Direct measurement of hydroxyl radicals, lipid peroxidation, and blood-brain barrier disruption following unilateral cortical impact head injury in the rat. J Neurotrauma. 1994;11:393–404. doi: 10.1089/neu.1994.11.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall ED, Detloff MR, Johnson K, Kupina NC. Peroxynitrite-mediated protein nitration and lipid peroxidation in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:9–20. doi: 10.1089/089771504772695904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radi R. Protein tyrosine nitration: biochemical mechanisms and structural basis of functional effects. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:550–559. doi: 10.1021/ar300234c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mesenge C, Charriaut-Marlangue C, Verrecchia C, Allix M, et al. Reduction of tyrosine nitration after N(omega)-nitro-L-arginine-methylester treatment of mice with traumatic brain injury. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;353:53–057. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee HM, Reed J, Greeley GH, Jr, Englander EW. Impaired mitochondrial respiration and protein nitration in the rat hippocampus after acute inhalation of combustion smoke. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;235:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang F, Li F, Chen G. Neuroprotective effect of apigenin in rats after contusive spinal cord injury. Neurol Sci. 2014;35:583–588. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1566-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bayir H, Kagan VE, Clark RS, Janesko-Feldman K, et al. Neuronal NOS-mediated nitration and inactivation of manganese superoxide dismutase in brain after experimental and human brain injury. J Neurochem. 2007;101:168–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lash LH, Jones DP. Distribution of oxidized and reduced forms of glutathione and cysteine in rat plasma. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;240:583–592. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drake J, Kanski J, Varadarajan S, Tsoras M, et al. Elevation of brain glutathione by gamma-glutamylcysteine ethyl ester protects against peroxynitrite-induced oxidative stress. J Neurosci Res. 2002;68:776–784. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reed TT, Owen J, Pierce WM, Sebastian A, et al. Proteomic identification of nitrated brain proteins in traumatic brain-injured rats treated postinjury with gamma-glutamylcysteine ethyl ester: insights into the role of elevation of glutathione as a potential therapeutic strategy for traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:408–417. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lok J, Leung W, Zhao S, Pallast S, et al. Gamma-glutamylcysteine ethyl ester protects cerebral endothelial cells during injury and decreases blood-brain barrier permeability after experimental brain trauma. J Neurochem. 2011;118:248–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun W, Liu J, Huan Y, Zhang C. Intracranial injection of recombinant stromal-derived factor-1 alpha (SDF-1alpha) attenuates traumatic brain injury in rats. Inflamm Res. 2014;63:287–297. doi: 10.1007/s00011-013-0699-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pandya JD, Pauly JR, Nukala VN, Sebastian AH, et al. Post-injury administration of mitochondrial uncouplers increases tissue sparing and improves behavioral outcome following traumatic brain injury in rodents. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:798–811. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.3673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durmaz R, Ertilav K, Akyuz F, Kanbak G, et al. Lazaroid U-74389G attenuates edema in rat brain subjected to post-ischemic reperfusion injury. J Neurol Sci. 2003;215:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(03)00207-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buki A, Koizumi H, Povlishock JT. Moderate posttraumatic hypothermia decreases early calpain-mediated proteolysis and concomitant cytoskeletal compromise in traumatic axonal injury. Exp Neurol. 1999;159:319–328. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li H, Lu G, Shi W, Zheng S. Protective effect of moderate hypothermia on severe traumatic brain injury in children. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1905–1909. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rezai AR, Sederberg PB, Bogner J, Nielson DM, et al. Improved function after deep brain stimulation for chronic, severe traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery. 2016;79:204–211. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullivan PG, Keller JN, Bussen WL, Scheff SW. Cytochrome c release and caspase activation after traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2002;949:88–96. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02968-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thongboonkerd V, McLeish KR, Arthur JM, Klein JB. Proteomic analysis of normal human urinary proteins isolated by acetone precipitation or ultracentrifugation. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1461–1469. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2002.kid565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller DM, Wang JA, Buchanan AK, Hall ED. Temporal and spatial dynamics of nrf2-antioxidant response elements mediated gene targets in cortex and hippocampus after controlled cortical impact traumatic brain injury in mice. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31:1194–1201. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bains M, Cebak JE, Gilmer LK, Barnes CC, et al. Pharmacological analysis of the cortical neuronal cytoskeletal protective efficacy of the calpain inhibitor SNJ-1945 in a mouse traumatic brain injury model. J Neurochem. 2013;125:125–132. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raghupathi R, McIntosh TK, Smith DH. Cellular responses to experimental brain injury. Brain Pathol. 1995;5:437–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1995.tb00622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeter CB, Hergenroeder GW, Ward NH, 3rd, Moore AN, et al. Human traumatic brain injury alters circulating L-arginine and its metabolite levels: possible link to cerebral blood flow, extracellular matrix remodeling, and energy status. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:119–127. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh IN, Sullivan PG, Deng Y, Mbye LH, et al. Time course of post-traumatic mitochondrial oxidative damage and dysfunction in a mouse model of focal traumatic brain injury: implications for neuroprotective therapy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1407–1418. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren Y, Xu HW, Davey F, Taylor M, et al. Endophilin I expression is increased in the brains of Alzheimer disease patients. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5685–5691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707932200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao M, Milosevic I, Giovedi S, De Camilli P. Upregulation of Parkin in endophilin mutant mice. J Neurosci. 2014;34:16544–16549. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1710-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frost B, Bardai FH, Feany MB. Lamin Dysfunction Mediates Neurodegeneration in Tauopathies. Curr Biol. 2016;26:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Opii WO, Nukala VN, Sultana R, Pandya JD, et al. Proteomic identification of oxidized mitochondrial proteins following experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:772–789. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fitzpatrick MO, Dewar D, Teasdale GM, Graham DI. The neuronal cytoskeleton in acute brain injury. Br J Neurosurg. 1998;12:313–317. doi: 10.1080/02688699844808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu CL, Chen S, Dietrich D, Hu BR. Changes in autophagy after traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:674–683. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lai Y, Hickey RW, Chen Y, Bayir H, et al. Autophagy is increased after traumatic brain injury in mice and is partially inhibited by the antioxidant gamma-glutamylcysteinyl ethyl ester. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:540–550. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delahunty TM, Jiang JY, Gong QZ, Black RT, et al. Differential consequences of lateral and central fluid percussion brain injury on receptor coupling in rat hippocampus. J Neurotrauma. 1995;12:1045–1057. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calabrese V, Scapagnini G, Colombrita C, Ravagna A, et al. Redox regulation of heat shock protein expression in aging and neurodegenerative disorders associated with oxidative stress: a nutritional approach. Amino Acids. 2003;25:437–444. doi: 10.1007/s00726-003-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lai Y, Kochanek PM, Adelson PD, Janesko K, et al. Induction of the stress response after inflicted and non-inflicted traumatic brain injury in infants and children. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:229–237. doi: 10.1089/089771504322972022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin ST, Heng MY, Ptacek LJ, Fu YH. Regulation of myelination in the central nervous system by nuclear lamin B1 and non-coding RNAs. Transl Neurodegener. 2014;3:4–11. doi: 10.1186/2047-9158-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heng MY, Lin ST, Verret L, Huang Y, et al. Lamin B1 mediates cell-autonomous neuropathology in a leukodystrophy mouse model. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2719–2729. doi: 10.1172/JCI66737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carr ME, Jr, Masullo LN, Brown JK, Lewis PC. Creatine kinase BB isoenzyme blood levels in trauma patients with suspected mild traumatic brain injury. Mil Med. 2009;174:622–625. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-02-4708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ingebrigtsen T, Romner B. Biochemical serum markers for brain damage: a short review with emphasis on clinical utility in mild head injury. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2003;21:171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hergenroeder GW, Redell JB, Moore AN, Dash PK. Biomarkers in the clinical diagnosis and management of traumatic brain injury. Mol Diagn Ther. 2008;12:345–358. doi: 10.1007/BF03256301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crawford F, Crynen G, Reed J, Mouzon B, et al. Identification of plasma biomarkers of TBI outcome using proteomic approaches in an APOE mouse model. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:246–260. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kay AD, Day SP, Kerr M, Nicoll JA, et al. Remodeling of cerebrospinal fluid lipoprotein particles after human traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2003;20:717–723. doi: 10.1089/089771503767869953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boyd-Kimball D, Sultana R, Abdul HM, Butterfield DA. Gamma-glutamylcysteine ethyl ester-induced up-regulation of glutathione protects neurons against Abeta(1-42)-mediated oxidative stress and neurotoxicity: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:700–706. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]