Abstract

Aggressive pain treatment was advocated for ESRD patients, but new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines recommend cautious opioid prescription. Little is known regarding outcomes associated with ESRD opioid prescription. We assessed opioid prescriptions and associations between opioid prescription and dose and patient outcomes using 2006–2010 US Renal Data System information in patients on maintenance dialysis with Medicare Part A, B, and D coverage in each study year (n=671,281, of whom 271,285 were unique patients). Opioid prescription was confirmed from Part D prescription claims. In the 2010 prevalent cohort (n=153,758), we examined associations of opioid prescription with subsequent all-cause death, dialysis discontinuation, and hospitalization controlled for demographics, comorbidity, modality, and residence. Overall, >60% of dialysis patients had at least one opioid prescription every year. Approximately 20% of patients had a chronic (≥90-day supply) opioid prescription each year, in 2010 usually for hydrocodone, oxycodone, or tramadol. In the 2010 cohort, compared with patients without an opioid prescription, patients with short-term (1–89 days) and chronic opioid prescriptions had increased mortality, dialysis discontinuation, and hospitalization. All opioid drugs associated with mortality; most associated with worsened morbidity. Higher opioid doses correlated with death in a monotonically increasing fashion. We conclude that opioid drug prescription is associated with increased risk of death, dialysis discontinuation, and hospitalization in dialysis patients. Causal relationships cannot be inferred, and opioid prescription may be an illness marker. Efforts to treat pain effectively in patients on dialysis yet decrease opioid prescriptions and dose deserve consideration.

Keywords: dialysis, end stage kidney disease, Epidemiology and outcomes, mortality, United States Renal Data System

Pain has been appreciated as important for patients with ESRD since the seminal work of Binik et al.1 >30 years ago. Pain is common among patients on dialysis,2–5 occurring in over 50% of patients, but its prevalence and severity vary in different areas and populations.3,6 Pain is linked to greater depressive affect and diminished quality of life in patients with and without kidney disease.3,4,6–12 Undertreatment of pain in patients on hemodialysis (HD) has also been reported,13,14 although treatment was defined as medication use in both studies. Over the last 15 years, aggressive pain treatment has been advocated for patients with ESRD.4,13,15,16

In the 1990s, the Joint Commission and the medical community focused on eradication of pain and its recognition as “the fifth vital sign.”17 Prescriptions of opioids for pain relief increased significantly18; however, as recently as 2000, no adverse health effects were noted.19 Subsequently, it was recognized that opioids were being overprescribed and associated with adverse outcomes.18,20,21 Over the last 5 years, high rates of opioid medication prescriptions and adverse effects associated with their use have become increasingly evident in the general population.18,22 The estimated total direct and indirect costs of opioid overdose in the United States were at least $18 billion in 2009.23 Recent guidelines developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend caution in opioid medication prescription.18 Although national trends in use and outcomes of opioids have been widely reported, data for patients on dialysis remain limited.24,25

We assessed the prevalence of opioid medication prescription in United States patients on maintenance dialysis and factors associated with prescription, and we determined associations between such chronic opioid prescription and dose and mortality, discontinuation of dialysis, and hospitalizations using data from the US Renal Data System (USRDS) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), including Medicare Part D files for prescription information.

Results

Table 1 shows the population of adult patients on dialysis with at least 365 days of dialysis treatment who were continuously enrolled (at least 365 days of enrollment) in Medicare Part A, B, and D in a specific year. There were 271,285 unique patients who were studied during 2006–2010, including approximately 100,000–154,000 such patients on dialysis each year.

Table 1.

Distribution by selected characteristics of adult patients on dialysis with continuous enrollment in Medicare Part A, B, and D, 2006–2010

| Characteristicsa | 2006, n=100,809, % | 2007, n=133,323, % | 2008, n=140,174, % | 2009, n=143,217, % | 2010, n=153,758, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid prescription | |||||

| None | 36.9 | 37.4 | 37.1 | 36.6 | 36.0 |

| Short term | 43.1 | 42.4 | 41.5 | 41.0 | 40.6 |

| Chronic | 20.0 | 20.2 | 21.4 | 22.3 | 23.4 |

| Analgesic prescription | |||||

| Yes | 15.2 | 14.2 | 13.9 | 14.0 | 14.2 |

| Age group, yr | |||||

| 20–44 | 19.3 | 17.4 | 17.1 | 16.8 | 16.4 |

| 45–64 | 42.5 | 42.2 | 42.5 | 43.1 | 43.5 |

| 65+ | 38.2 | 40.4 | 40.5 | 40.1 | 40.2 |

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 49.4 | 51.4 | 51.8 | 51.9 | 52.2 |

| Race | |||||

| Black | 45.8 | 43.7 | 42.9 | 42.4 | 42.0 |

| White | 48.1 | 50.6 | 51.3 | 51.8 | 52.2 |

| Other | 6.1 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5.8 |

| Dual statusb | |||||

| Yes | 85.3 | 72.6 | 71.8 | 71.3 | 70.9 |

| Residential area | |||||

| Large metropolitan | 52.0 | 50.9 | 51.0 | 51.2 | 51.3 |

| Medium/small metropolitan | 28.9 | 29.7 | 29.7 | 29.8 | 29.7 |

| Nonmetropolitan | 19.1 | 19.5 | 19.4 | 19.1 | 19.0 |

| ESRD vintage, yr | |||||

| 1–2 | 18.0 | 18.1 | 17.1 | 16.9 | 16.6 |

| 3–4 | 31.3 | 31.2 | 31.3 | 30.5 | 29.6 |

| 5+ | 50.8 | 50.7 | 51.7 | 52.7 | 53.8 |

| Dialysis modalityc | |||||

| HD | 94.6 | 94.2 | 94.3 | 94.4 | 94.3 |

| History of kidney transplantation | |||||

| Yes | 7.9 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.6 |

| Nursing home residenced | |||||

| Yes | 11.4 | 10.5 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 11.5 |

| Cancere | |||||

| Yes | 4.4 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 5.4 |

| Prior pain-related hospitalization | |||||

| Yes | 5.1 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.7 |

| No. of prior hospitalizations | |||||

| 0 | 38.8 | 40.3 | 40.9 | 41.4 | 41.9 |

| 1–2 | 34.6 | 35.3 | 34.4 | 34.3 | 34.5 |

| 3–4 | 14.7 | 14.0 | 13.7 | 13.5 | 13.4 |

| 5 or more | 11.9 | 10.5 | 11.0 | 10.8 | 10.2 |

The same patient might have been included in multiple years.

Dual status in Medicare and Medicaid.

The last modality in the study year.

On the basis of one or more claims in physician/carrier files.

On the basis of one or more inpatient stays with a cancer diagnosis and CMS Form 2728.

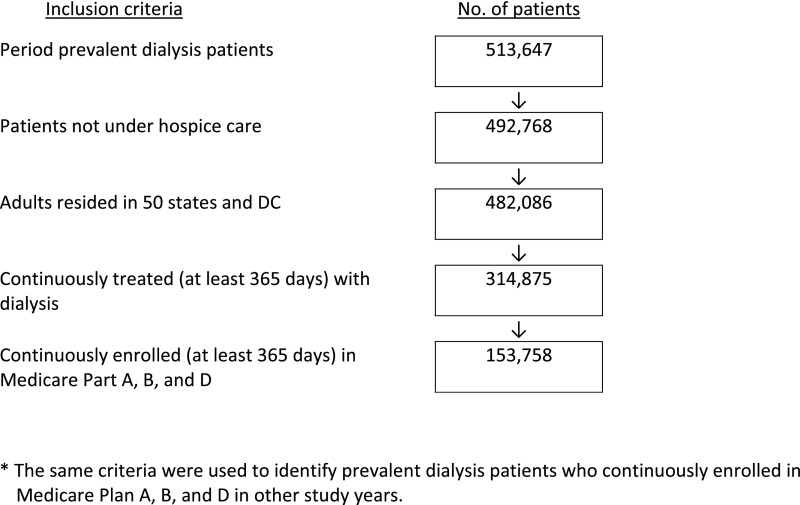

The study population (n=153,758 in 2010) was different from the parent ESRD population (n=513,647) (Figure 1) in that it had proportionally more women, was younger, had more black patients, and had more patients with a greater number of hospitalizations in 2010 (Supplemental Table 1). The study population was predominantly men and disproportionately black, consistent with the Medicare ESRD dialysis population.

Figure 1.

Selection of prevalent patients on dialysis continuously enrolled in Medicare Part A, B, and D in 2010.

More than 94% were treated with HD; <8% had had renal transplantation. About three quarters were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, reflecting the fact that all dual coverage beneficiaries receive Part D coverage, an option for other patients. Over one half had ESRD vintage >4 years, had one or more prior hospital admissions, and lived in large metropolitan areas. About 11% were nursing home residents (Table 1).

During 2006–2010, >60% of patients with ESRD on dialysis received a prescription for an opioid medication (63.1% in 2006 and 64.0% in 2010; data not shown). The total medication cost increased from $29 million in 2006 to $49 million in 2010 (data not shown). During the study period, over 20% of patients on dialysis (20.0% in 2006 and 23.4% in 2010) had ≥90 days of filled chronic opioid prescriptions (Table 2). Over 50% of patients on dialysis had opioid prescriptions only (53.0% in 2006 and 51.4% in 2010), 32% (34.0% in 2006 and 32.8% in 2010) had neither analgesic nor opioid prescriptions, over 10% had both opioid and analgesic prescriptions (10.6% in 2008 and 11.0% in 2010), and about 3% had an analgesic prescription only (3.5% in 2006 and 3.2% in 2010).

Table 2.

Percentage of adult patients on dialysis continuously enrolled in Medicare Part A, B, and D who had prescriptions for ≥90 days of an opioid by year

| Characteristicsa | 2006, % | 2007, % | 2008, % | 2009, % | 2010, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 20.0 | 20.2 | 21.4 | 22.3 | 23.4 |

| Age group, yr | |||||

| 20–44 | 20.1 | 20.3 | 22.0 | 23.3 | 24.2 |

| 45–64 | 22.8 | 23.4 | 25.0 | 26.1 | 27.4 |

| 65+ | 16.9 | 16.8 | 17.2 | 17.9 | 18.8 |

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 18.0 | 18.2 | 19.4 | 20.5 | 21.4 |

| Women | 22.0 | 22.3 | 23.5 | 24.4 | 25.6 |

| Race | |||||

| Black | 19.5 | 19.9 | 21.2 | 22.7 | 24.2 |

| White | 21.8 | 21.5 | 22.6 | 23.3 | 24.0 |

| Other | 10.6 | 12.0 | 11.9 | 11.7 | 12.8 |

| Dual statusb | |||||

| No | 12.8 | 13.6 | 14.4 | 14.9 | 16.0 |

| Yes | 21.3 | 22.7 | 24.1 | 25.4 | 26.5 |

| Residential area | |||||

| Large metropolitan | 17.6 | 18.0 | 18.8 | 19.8 | 20.9 |

| Medium/small metropolitan | 22.3 | 22.3 | 23.5 | 24.4 | 25.7 |

| Nonmetropolitan | 23.3 | 23.0 | 25.0 | 25.9 | 26.7 |

| ESRD vintage, yr | |||||

| 1–2 | 18.7 | 19.7 | 20.2 | 21.1 | 22.1 |

| 3–4 | 19.0 | 19.1 | 20.5 | 21.4 | 22.3 |

| 5+ | 21.1 | 21.0 | 22.3 | 23.3 | 24.4 |

| Dialysis modalityc | |||||

| HD | 20.4 | 20.6 | 21.7 | 22.8 | 23.8 |

| PD | 14.2 | 14.3 | 15.1 | 15.3 | 16.7 |

| History of kidney transplantation | |||||

| No | 19.8 | 20.0 | 21.1 | 22.2 | 23.2 |

| Yes | 23.1 | 23.2 | 24.7 | 24.6 | 25.7 |

| Nursing home residenced | |||||

| No | 19.2 | 19.4 | 20.6 | 21.5 | 22.6 |

| Yes | 26.3 | 27.3 | 28.0 | 29.2 | 29.8 |

| Cancere | |||||

| No | 19.9 | 20.1 | 21.2 | 22.3 | 23.3 |

| Yes | 23.5 | 22.8 | 23.8 | 23.7 | 24.9 |

| Prior pain-related hospitalization | |||||

| No | 19.0 | 18.9 | 19.8 | 20.8 | 21.6 |

| Yes | 40.1 | 42.4 | 46.4 | 46.7 | 49.5 |

| No. of prior hospitalizations | |||||

| 0 | 13.4 | 13.7 | 14.9 | 15.7 | 16.3 |

| 1–2 | 20.0 | 20.3 | 21.3 | 22.4 | 24.0 |

| 3–4 | 26.2 | 27.7 | 28.6 | 29.5 | 31.5 |

| 5 or more | 34.2 | 34.7 | 36.4 | 38.4 | 39.9 |

The percentages of patients who had chronic prescriptions were significantly different across groups in each characteristic (P<0.01 for all comparisons).

Filled prescription for a 90-day or more supply within the study year.

Dual status in Medicare and Medicaid.

The last modality in the study year.

On the basis of one or more claims in physician/carrier files.

On the basis of one or more inpatient stays with a cancer diagnosis and CMS Form 2728.

Approximately 15% of patients on peritoneal dialysis (PD; 14.2% in 2006 and 16.7% in 2010) had ≥90 days of filled chronic opioid prescriptions. Patients who previously received kidney transplantation and were currently treated with dialysis had chronic opioid prescription rates of 23.1% (2006) to 25.7% (2010), consistently higher than those in patients who had never had a transplant.

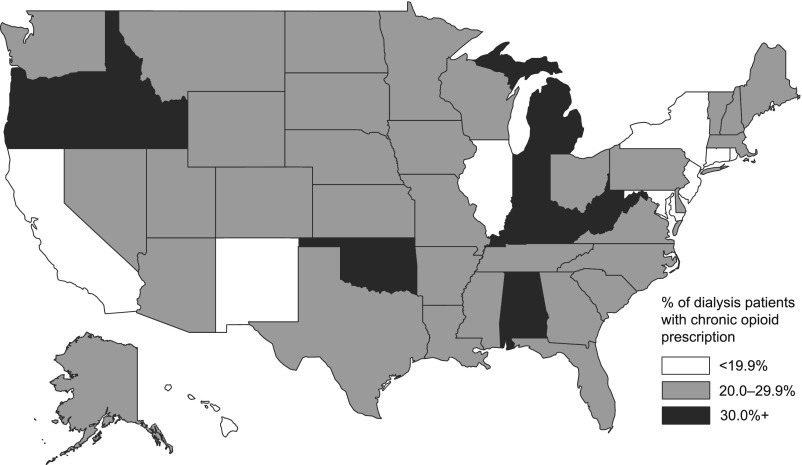

Chronic opioid prescription rates ranged from 9.5% of patients on dialysis in Hawaii to 40.6% of patients in West Virginia in 2010. Seven other states had prescription rates >30% (Michigan, Oklahoma, Oregon, Kentucky, Idaho, Indiana, and Alabama) (Figure 2). Highest dialysis patient opioid prescription rates were among women, patients 45–64 years old, and nursing home residents. Dual status dialysis patients had a higher rate of chronic opioid prescription. Prior pain-related hospitalizations were associated with higher chronic opioid prescription as was a greater number of hospitalizations (all P<0.01).

Figure 2.

Geographic variation in the percentage of patients on dialysis with chronic opioid prescription in 2010 by state.

The opioids most commonly prescribed for ≥90 days during 2006–2010 were hydrocodone (increasing from 8.6% in 2006 to 11.7% in 2010) and oxycodone (increasing from 4.1% in 2006 to 5.4% in 2010). The third most commonly prescribed opioid for ≥90 days was propoxyphene in 2006–2007 (approximately 2.2%) and tramadol in 2008–2010 (2.1%–2.5%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage of patients on dialysis who had a prescription for ≥90 days of a specific opioid by year

| Opioida | 2006, % | 2007, % | 2008, % | 2009, % | 2010, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dialysis | |||||

| Hydrocodone | 8.6 | 9.0 | 10.1 | 10.9 | 11.7 |

| Oxycodone | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 5.4 |

| Propoxyphene | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.4 |

| Tramadol | 1.7 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.5 |

| Codeine | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Morphine | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Hydromorphone | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Fentanyl | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| HD | |||||

| Hydrocodone | 8.8 | 9.2 | 10.2 | 11.1 | 11.9 |

| Oxycodone | 4.1 | 4.3 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 5.6 |

| Propoxyphene | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.4 |

| Tramadol | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.6 |

| Codeine | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Morphine | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Hydromorphone | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Fentanyl | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| PD | |||||

| Hydrocodone | 6.1 | 6.4 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 8.5 |

| Oxycodone | 3.4 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 3.4 |

| Propoxyphene | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.3 |

| Tramadol | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.7 |

| Codeine | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Morphine | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Hydromorphone | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Fentanyl | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

Chronic use is not mutually exclusive; a person could have a ≥90-day prescription for more than one opioid medication.

Filled prescription for a 90-day or more supply within the study year.

Table 4 shows factors associated with chronic prescription of any opioid in 2010 dialysis patients, adjusting for all listed characteristics. Chronic opioid prescription was independently associated with women (odds ratio [OR], 1.21; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.18 to 1.24), white race (compared with black race; OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.15), nursing home residence (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.18), dual status (OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.55 to 1.65), cancer diagnosis (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.19), and prior pain-related hospitalizations in 2010 (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 2.18 to 2.38).

Table 4.

Factors associated with prescription for ≥90 days of an opioid in adult patients on dialysis continuously enrolled in Medicare Part A, B, and D, 2010 (n=153,540)

| Characteristics | OR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Men | 1.00 | ||

| Women | 1.21 | 1.18 to 1.24 | <0.001 |

| Race | |||

| Black | 1.00 | ||

| White | 1.12 | 1.09 to 1.15 | <0.001 |

| Other | 0.51 | 0.47 to 0.54 | <0.001 |

| Age group, yr | |||

| 20–44 | 1.28 | 1.23 to 1.33 | <0.001 |

| 45–64 | 1.59 | 1.54 to 1.63 | <0.001 |

| 65+ | 1.00 | ||

| ESRD vintage, yr | |||

| 1–2 | 1.00 | ||

| 3–4 | 1.01 | 0.97 to 1.05 | 0.57 |

| 5+ | 1.12 | 1.08 to 1.16 | <0.001 |

| Dialysis modality | |||

| HD | 1.00 | ||

| PD | 0.68 | 0.64 to 0.72 | <0.001 |

| History of kidney transplantation | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.02 | 0.97 to 1.07 | 0.45 |

| Analgesic prescription | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.59 | 1.54 to 1.64 | <0.001 |

| Dual statusa | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.60 | 1.55 to 1.65 | <0.001 |

| Residential area | |||

| Large metropolitan | 1.00 | ||

| Medium/small metropolitan | 1.36 | 1.32 to 1.40 | <0.001 |

| Nonmetropolitan | 1.52 | 1.47 to 1.57 | <0.001 |

| Nursing home residenceb | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.14 | 1.09 to 1.18 | <0.001 |

| Cancerc | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.13 | 1.07 to 1.19 | <0.001 |

| Prior pain-related hospitalization in 2010 | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 2.28 | 2.18 to 2.38 | <0.001 |

| No. of prior hospitalizations in 2010 | |||

| 0 | 1.00 | ||

| 1–2 | 1.48 | 1.44 to 1.52 | <0.001 |

| 3–4 | 1.98 | 1.91 to 2.06 | <0.001 |

| 5 or more | 2.42 | 2.32 to 2.53 | <0.001 |

All variables presented in the table were adjusted in the logistic regression model.

Dual status in Medicare and Medicaid.

On the basis of one or more claims in physician/carrier files.

On the basis of one or more inpatient stays with a cancer diagnosis and CMS Form 2728.

Patients on PD were less likely to have received a chronic opioid prescription than patients on HD (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.64 to 0.72; P<0.001). There was no difference between the proportions of patients with or without a history of kidney transplantation who received chronic opioid prescriptions. Younger patients had higher opioid prescription rates. Compared with patients age 65 years old or older, the ORs (95% CIs) in those 20–44 and 45–64 years old were OR, 1.28 (95% CI, 1.23 to 1.33) and OR, 1.59 (95% CI, 1.54 to 1.63), respectively. Compared with patients with 1–2 years ESRD vintage, the odds of a chronic opioid prescription were 12% (95% CI, 1.08 to 1.16) greater for patients with 5 or more years ESRD vintage.

Patients who received a prescription for nonopioid analgesics were more likely to have received an opioid prescription as well (OR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.54 to 1.64; P<0.001). Patients living in rural (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.47 to 1.57) and medium/small metropolitan areas (1.36; 95% CI, 1.32 to 1.40) had greater likelihood of chronic opioid prescription than those living in large metropolitan areas. There was a greater likelihood of opioid prescription associated with greater numbers of hospitalizations in 2010 (OR increasing from 1.48 [95% CI, 1.44 to 1.52] for one to two admissions to 2.42 [95% CI, 2.32 to 2.53] for more than four admissions).

Differences existed among patients who received short-term and chronic opioid prescriptions compared with those who did not in the 2010 dialysis cohort (Table 5). A majority of patients on dialysis who received either short-term or chronic opioid prescriptions had morphine milligram equivalent (MME) doses >20/d. There was no difference between the proportions of patients with a history of kidney transplantation who received short-term or chronic opioid prescriptions in 2010. Of patients who received an analgesic prescription, 15.7% received short-term opioid prescriptions, and 19.7% received chronic opioid prescriptions (Table 5).

Table 5.

Characteristics of patients on dialysis by status of opioid prescription in the 2010 prevalent cohort

| Characteristicsa | All, n=153,758 | Nonuser, n=55,367 | Short-Term Prescription, n=62,401 | Chronic Prescription, n=35,990 | P Value for Overall Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid prescription, MME/d | <0.001 | ||||

| <20 | 17.8 | 20.1 | |||

| 20–50 | 56.8 | 46.7 | |||

| 50+ | 25.4 | 33.2 | |||

| Men | 52.2 | 58.2 | 49.5 | 47.7 | <0.001 |

| Race | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 52.2 | 53.1 | 50.7 | 53.5 | |

| Black | 42.0 | 38.8 | 44.1 | 43.4 | |

| Other | 5.8 | 8.1 | 5.2 | 3.2 | |

| Age group, yr | <0.001 | ||||

| 20–44 | 16.4 | 14.3 | 17.9 | 17.0 | |

| 45–64 | 43.5 | 39.7 | 42.5 | 50.8 | |

| 65+ | 40.2 | 46.0 | 39.5 | 32.2 | |

| ESRD, yr | <0.001 | ||||

| 1–2 | 16.6 | 15.1 | 18.5 | 15.7 | |

| 3–4 | 29.6 | 31.4 | 28.8 | 28.1 | |

| 5+ | 53.8 | 53.6 | 52.7 | 56.2 | |

| Dialysis modality | <0.001b | ||||

| HD | 94.3 | 93.7 | 93.9 | 95.9 | |

| PD | 5.7 | 6.3 | 6.1 | 4.1 | |

| History of kidney transplantation | 7.6 | 6.7 | 7.9 | 8.3 | <0.001c |

| Analgesic prescription | 14.2 | 8.9 | 15.7 | 19.7 | <0.001 |

| Dual statusd | 70.9 | 63.7 | 72.1 | 80.2 | <0.001 |

| Residential area | <0.001 | ||||

| Large metropolitan | 51.3 | 56.2 | 50.1 | 45.9 | |

| Medium/small metropolitan | 29.7 | 27.3 | 30.2 | 32.5 | |

| Nonmetropolitan | 19.0 | 16.5 | 19.7 | 21.6 | |

| Nursing home residencee | 11.5 | 8.5 | 12.3 | 14.6 | <0.001 |

| Cancerf | 5.4 | 4.9 | 5.6 | 5.8 | <0.001c |

| Prior pain-related hospitalization | 6.7 | 2.1 | 6.5 | 14.1 | <0.001 |

| No. of prior hospitalizations | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 41.9 | 58.2 | 34.8 | 29.3 | |

| 1–2 | 34.5 | 29.9 | 38.2 | 35.4 | |

| 3–4 | 13.4 | 7.8 | 15.6 | 18.0 | |

| 5 or more | 10.2 | 4.1 | 11.5 | 17.4 | |

| Smoker | 6.8 | 5.1 | 6.3 | 10.3 | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 25.2 | 24.1 | 25.1 | 27.2 | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 9.8 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 11.1 | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 0.50 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 5.2 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 7.2 | <0.001 |

| Atherosclerotic heart disease | 15.5 | 15.7 | 15.1 | 15.9 | <0.001g |

| Diabetes | 54.4 | 52.3 | 55.5 | 55.9 | <0.001c |

| AIDS | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.1 | <0.001c |

Values are expressed as percentages. Chi-squared test was used for overall (three-group) and three-pair (nonuser versus short-term prescription, nonuser versus chronic prescription, and short-term prescription versus chronic prescription) comparisons. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.017 using two-tailed tests on the basis of the Bonferroni method for paired multiple comparison.

Short term: 1- to 89-day supply within the study year; chronic: 90-day or more supply within the study year.

The difference between nonusers and short-term prescription was not significant; other comparisons were significant.

The difference between short-term prescription and chronic prescription was not significant; other comparisons were significant.

Dual status in Medicare and Medicaid.

On the basis of one or more claims in physician/carrier files.

On the basis of one or more inpatient stays with a cancer diagnosis and CMS Form 2728.

The difference between nonusers and chronic prescription was not significant; other comparisons were significant.

Table 6 shows associations of short-term and chronic opioid prescription in 2010 with subsequent all-cause death, discontinuation of dialysis, and hospitalization in the 2010 prevalent dialysis cohort. Mortality was increased in patients with short-term prescriptions and in all categories of long-term prescriptions. After adjustment for covariates, patients on dialysis with short-term opioid prescriptions had slightly increased risks of death (hazard ratio [HR], 1.05; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.07), discontinuation of dialysis (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.22), and hospitalization (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.14) compared with patients on dialysis who had not received an opioid prescription. The risks of death, discontinuation of dialysis, and hospitalization for patients who received chronic opioid prescription increased monotonically as the MME dose increased from <20 to >50. Black patients were less likely than white patients to experience such events, but patients on PD were more likely than patients on HD to experience such events. As the age and vintage of patients on dialysis who received chronic opioid prescriptions increased, they were more likely to experience such events.

Table 6.

Adjusted HRs of death, discontinued dialysis, and hospitalization in 2011–2012 associated with 2010 prescription for ≥90 days of an opioid in the 2010 prevalent dialysis cohort (n=149,757)

| Characteristics | Outcome: Death | Outcome: Discontinued Dialysis | Outcome: Hospitalization | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Opioid prescriptiona | |||||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Short term | 1.05 | 1.02 to 1.07 | <0.001 | 1.13 | 1.05 to 1.22 | 0.002 | 1.13 | 1.11 to 1.14 | <0.001 |

| Chronic, <20 MME/d | 1.16 | 1.11 to 1.21 | <0.001 | 1.32 | 1.15 to 1.53 | <0.001 | 1.26 | 1.22 to 1.29 | <0.001 |

| Chronic, 20–50 MME/d | 1.26 | 1.22 to 1.30 | <0.001 | 1.36 | 1.22 to 1.51 | <0.001 | 1.29 | 1.27 to 1.32 | <0.001 |

| Chronic, 50+ MME/d | 1.39 | 1.34 to 1.44 | <0.001 | 1.47 | 1.30 to 1.66 | <0.001 | 1.38 | 1.35 to 1.41 | <0.001 |

| Analgesic prescription | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 0.96 | 0.93 to 0.98 | 0.001 | 0.94 | 0.85 to 1.03 | 0.16 | 1.03 | 1.02 to 1.05 | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Women | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Men | 1.11 | 1.09 to 1.13 | <0.001 | 0.88 | 0.83 to 0.94 | <0.001 | 0.95 | 0.94 to 0.96 | <0.001 |

| Race | |||||||||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Black | 0.82 | 0.80 to 0.83 | <0.001 | 0.61 | 0.57 to 0.66 | <0.001 | 0.96 | 0.95 to 0.98 | <0.001 |

| Other | 0.93 | 0.89 to 0.98 | 0.002 | 0.66 | 0.56 to 0.78 | <0.001 | 0.93 | 0.91 to 0.95 | <0.001 |

| Age group, yr | |||||||||

| 20–44 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 45–64 | 1.78 | 1.71 to 1.85 | <0.001 | 2.26 | 1.88 to 2.71 | <0.001 | 1.05 | 1.03 to 1.06 | <0.001 |

| 65+ | 3.06 | 2.93 to 3.19 | <0.001 | 6.83 | 5.70 to 8.19 | <0.001 | 1.20 | 1.18 to 1.22 | <0.001 |

| ESRD vintage, yr | |||||||||

| 1–2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 3–4 | 1.14 | 1.11 to 1,18 | <0.001 | 1.01 | 0.93 to 1.10 | 0.80 | 1.07 | 1.05 to 1.09 | <0.001 |

| 5+ | 1.29 | 1.26 to 1.33 | <0.001 | 1.02 | 0.93 to 1.10 | 0.72 | 1.09 | 1.08 to 1.11 | <0.001 |

| Dialysis modality | |||||||||

| HD | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| PD | 1.29 | 1.23 to 1.35 | <0.001 | 1.21 | 1.06 to 1.40 | 0.01 | 1.16 | 1.13 to 1.19 | <0.001 |

| History of kidney transplantation | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 0.88 | 0.84 to 0.93 | <0.001 | 0.66 | 0.54 to 0.81 | <0.001 | 0.99 | 0.97 to 1.01 | 0.37 |

| Dual statusb | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 0.91 | 0.89 to 0.93 | <0.001 | 0.75 | 0.70 to 0.81 | <0.001 | 1.01 | 1.00 to 1.03 | 0.04 |

| Residential area | |||||||||

| Large | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Medium/small | 1.01 | 0.99 to 1.04 | 0.27 | 1.58 | 1.47 to 1.70 | <0.001 | 0.96 | 0.95 to 0.98 | <0.001 |

| Nonmetropolitan | 1.11 | 1.08 to 1.13 | <0.001 | 1.73 | 1.59 to 1.87 | <0.001 | 0.92 | 0.91 to 0.93 | <0.001 |

| Nursing home residencec | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.56 | 1.52 to 1.60 | <0.001 | 2.24 | 2.07 to 2.42 | <0.001 | 1.08 | 1.06 to 1.10 | <0.001 |

| Cancerd | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.26 | 1.21 to 1.30 | <0.001 | 1.40 | 1.26 to 1.55 | <0.001 | 1.04 | 1.01 to 1.07 | 0.003 |

| Prior pain-related hospitalization in 2010 | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 0.95 | 0.92 to 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.97 | 0.86 to 1.10 | 0.66 | 1.16 | 1.13 to 1.18 | <0.001 |

| No. of prior hospitalizations in 2010 | |||||||||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 1–2 | 1.55 | 1.52 to 1.59 | <0.001 | 1.42 | 1.31 to 1.54 | <0.001 | 1.56 | 1.54 to 1.58 | <0.001 |

| 3–4 | 2.17 | 2.11 to 2.24 | <0.001 | 1.85 | 1.67 to 2.04 | <0.001 | 2.34 | 2.30 to 2.39 | <0.001 |

| 5 or more | 3.05 | 2.95 to 3.15 | <0.001 | 2.58 | 2.32 to 2.87 | <0.001 | 3.63 | 3.55 to 3.71 | <0.001 |

| Smoker | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.13 | 1.09 to 1.18 | <0.001 | 1.26 | 1.11 to 1.42 | <0.001 | 1.07 | 1.05 to 1.10 | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.20 | 1.17 to 1.23 | <0.001 | 1.07 | 1.00 to 1.15 | 0.05 | 1.06 | 1.04 to 1.07 | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.08 | 1.05 to 1.11 | <0.001 | 1.14 | 1.04 to 1.25 | <0.01 | 1.03 | 1.00 to 1.05 | 0.02 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.03 | 0.99 to 1.07 | 0.10 | 1.29 | 1.17 to 1.43 | <0.001 | 1.03 | 1.01 to 1.05 | 0.01 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.12 | 1.08 to 1.17 | <0.001 | 1.11 | 0.99 to 1.24 | 0.08 | 1.13 | 1.10 to 1.15 | <0.001 |

| Atherosclerotic heart disease | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.14 | 1.11 to 1.17 | <0.001 | 1.06 | 0.98 to 1.15 | 0.14 | 1.07 | 1.05 to 1.09 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.18 | 1.15 to 1.20 | <0.001 | 0.88 | 0.82 to 0.94 | <0.001 | 1.13 | 1.12 to 1.14 | <0.001 |

| AIDS | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.19 | 1.06 to 1.34 | 0.003 | 1.24 | 0.76 to 2.00 | 0.39 | 1.12 | 1.06 to 1.19 | <0.001 |

Short term: 1- to 89-day filled prescription supply within the study year; chronic: 90-day or more filled prescription supply within the study year.

Dual status in Medicare and Medicaid.

On the basis of one or more claims in physician/carrier files.

On the basis of one or more inpatient stays with a cancer diagnosis and CMS Form 2728.

Patients who had renal transplantation were less likely to die or discontinue dialysis than those who had not had renal transplantation. Patients who received a nonopioid analgesic prescription were less likely to die during the observation period but more likely to be hospitalized than those who had not had such a prescription.

Table 7 shows associations of subsequent all-cause death, discontinuation of dialysis, and hospitalization with the common individual chronic prescribed opioid/narcotic agents in the 2010 prevalent dialysis cohort. All individual opioids prescribed were associated with significantly increased risk of death. Codeine prescription was not significantly associated with dialysis discontinuation risk (HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 0.88 to 1.90), but the number of codeine prescriptions was relatively small. Prescription of any of the individual drugs was associated with significantly increased hospitalization risk. Chronic prescriptions of hydrocodone, oxycodone, propoxyphene, morphine, hydromorphone, and fentanyl were significantly associated with increased risk of discontinuation of dialysis.

Table 7.

Adjusted HRs of death, discontinued dialysis, and hospitalization associated with specific opioid prescription in 2010 prevalent dialysis cohort

| Specific Opioid | N | Outcome: Death | Outcome: Discontinued Dialysis | Outcome: Hospitalization | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | ||

| Hydrocodone | ||||||||||

| Nonusera | 55,367 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Chronicb | 18,006 | 1.29 | 1.24 to 1.33 | <0.001 | 1.36 | 1.22 to 1.52 | <0.001 | 1.29 | 1.26 to 1.32 | <0.001 |

| Oxycodone | ||||||||||

| Nonusera | 55,367 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Chronicb | 8357 | 1.33 | 1.27 to 1.39 | <0.001 | 1.57 | 1.35 to 1.84 | <0.001 | 1.40 | 1.36 to 1.44 | <0.001 |

| Propoxyphene | ||||||||||

| Nonusera | 55,367 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Chronicb | 2124 | 1.33 | 1.23 to 1.43 | <0.001 | 1.47 | 1.17 to 1.85 | 0.001 | 1.23 | 1.17 to 1.29 | <0.001 |

| Tramadol | ||||||||||

| Nonusera | 55,367 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Chronicb | 3876 | 1.18 | 1.11 to 1.26 | <0.001 | 1.14 | 0.93 to 1.39 | 0.21 | 1.25 | 1.20 to 1.30 | <0.001 |

| Codeine | ||||||||||

| Nonusera | 55,367 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Chronicb | 976 | 1.13 | 1.001 to 1.27 | 0.05 | 1.29 | 0.88 to 1.90 | 0.19 | 1.29 | 1.20 to 1.39 | <0.001 |

| Morphine | ||||||||||

| Nonusera | 55,367 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Chronicb | 1025 | 1.56 | 1.40 to 1.74 | <0.001 | 1.92 | 1.37 to 2.69 | <0.001 | 1.54 | 1.44 to 1.65 | <0.001 |

| Hydromorphone | ||||||||||

| Nonusera | 55,367 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Chronicb | 867 | 1.65 | 1.47 to 1.85 | <0.001 | 2.58 | 1.83 to 3.64 | <0.001 | 1.58 | 1.46 to 1.70 | <0.001 |

| Fentanyl | ||||||||||

| Nonusera | 55,367 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Chronicb | 1926 | 1.39 | 1.29 to 1.50 | <0.001 | 1.59 | 1.26 to 1.99 | <0.001 | 1.31 | 1.24 to 1.38 | <0.001 |

Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for sex, race, age, year of ESRD, dialysis modality, analgesic prescriptions, history of kidney transplantation, dual status, residential area, nursing home residence, cancer, pain-related hospitalization in 2010, number of hospitalization in 2010, and comorbidities reported in CMS Form 2728 (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, atherosclerotic heart disease, diabetes, AIDS, and smoking) in each model.

A 0-day supply within the study year.

A 90-day or more supply within the study year.

We conducted two sensitivity analyses to assess whether our results were consistent with new use research. First, we subdivided our sample of 2010 patients with ESRD to eliminate all patients who had any opioid prescription in the 6 months before January 1, 2010 (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). The results were similar to those of the main analysis. Short-term opioid prescription was not associated with mortality, but it was associated with hospitalization. Chronic high dose prescription was associated with increased mortality, and there was a stepwise increase in mortality associated with increasing dose levels.

Second, we assessed first use patients in 2010 (Supplemental Tables 4 and 5). Analyses of first use did not show significant associations with mortality, dialysis discontinuation, or hospitalization (Supplemental Tables 4 and 5). Neither sensitivity analysis contradicted findings regarding long-term chronic opioid use.

Discussion

Almost two thirds of patients on dialysis received at least one opioid prescription every year, and over 20% received chronic prescriptions (≥90 days of filled prescriptions), three times as great as the rate of chronic opioid prescription in the general Medicare population.22 Over one quarter of opioid users received doses exceeding CDC or other recommendations. Although the cost of these prescriptions in 2010 was not great ($49 million), the potential clinical effect of this use is important, because both chronic use and high-dose prescriptions are associated with increased risk of death and adverse events.

Opioid prescription in patients on dialysis has increased over time, and the demographic and geographic trends seem to be similar to those in the general population.22 Eight states had chronic opioid prescription rates of 30% or more. The reasons for this are unknown but probably reflect differential physician practice. Such regional variation provides opportunities for intervention.

United States general population death rates attributable to opioid overdose increased fivefold from 0.08 to 0.38 per 100,000 from 1993 to 2009.26 Total prescription opioid overdose events nearly tripled from 8815 hospitalizations in 1999 to 22,907 hospitalizations in 2006. Opioid prescriptions at hospital discharge were associated with subsequent chronic opioid use.27

Chronic (≥90-day) prescription of opioids increased in the general Medicare population from 4.6% in 2007 to 7.4% in 2012 in an analysis limited to Schedule II and III drugs, excluding patients with cancer diagnoses or residing in nursing homes.22 Similar to the general population and other analyses, in this study, chronic opioid prescription was most common among white patients on dialysis, those not living in large metropolitan areas, and those living in poverty. We found that the most commonly prescribed opioids for patients on dialysis were similar to those previously reported earlier in patients on dialysis.25 Such prescription is also similar to that in the general population, where hydrocodone accounted for 51% and oxycodone accounted for 16% of prescriptions.28 Prescription of these drugs to patients on dialysis does not take into account specific recommendations for use or avoidance in this population.29 However, our results may reflect a different study population relative to the study by Kuo et al.22 because of the over-representation of dual eligibility patients on dialysis.

The associations that we show between opioid prescriptions and dialysis patient mortality are striking. All commonly prescribed medications were associated with an increased risk of death. In addition, most of the commonly prescribed opioid medications were associated with increased adverse events, specifically discontinuation of dialysis and all-cause hospitalization in the dialysis population. Similar to the general Medicare population, rural residents were more likely to receive opioid prescriptions. As expected, opioid prescription was more common in patients with cancer, those residing in nursing homes, those with prior hospitalization, or those who had a pain-related hospitalization.

It is important that hospitalization, perhaps because of the relationship of ESRD patients with new physicians, does not become a reason for opioid prescription in this population.30 In addition, opioid prescription was more common in ESRD patients of greater vintage, suggesting that this may be a response to the ongoing burden of long-standing dialysis. In the general Medicare population, overall chronic opioid prescriptions were associated with increased risk of both emergency room visits and hospitalizations.22 Use of long-acting opioids, compared with anticonvulsants or tricyclic antidepressants, was associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality in Tennessee Medicaid patients with chronic noncancer pain, consistent with our findings.31

The CDC recently released clinical guidelines for opioid prescription,18 including checklists for provider use. The guidelines call for increased patient/physician discussions before prescription, during treatment, during decision on pain management therapeutic plans before prescription, and during follow-up visits. The lowest dose and duration of opioid treatment are recommended, and nonopioid approaches are considered essential. This is critical, because many previous assessments of pain control, including in the dialysis population, primarily considered analgesic and opioid drug prescriptions as appropriate treatment for pain and gave less emphasis to nonpharmacologic therapies, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), psychotherapy, and biofeedback techniques.11,12,32

Certain aspects of pain in patients on dialysis are unique and complicate management. Muscle cramps in particular are frequently present in patients on dialysis.29 Opioid use is not recommended for this symptom. Pain syndromes occurring during dialysis treatment include pain at the dialysis access site as well as headaches. Step therapy is problematic in patients on dialysis, because the National Kidney Foundation recommends acetaminophen as the preferred non-narcotic analgesic for mild to moderate pain, with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs not preferred but considered for short-term use.33

Another key finding is that adverse events in this study were strongly associated with increased opioid dose prescribed. Although dosing of opioid medications in patients on dialysis is complex, because mortality in this study was related to dose, our data suggest that the lowest dose be prescribed.

Treatment of opioid addiction in patients on dialysis presents unique challenges. Buprenorphine may be a promising therapy for patients on dialysis with opioid addiction.34 Naloxone, which has been advocated for more generalized release for use in populations at risk for overdose, was recently used in a randomized trial assessing prevention of opioid relapse.35 In contrast to the general population, where CBT has been assessed and found effective for pain management in clinical trials,36,37 no reports of its efficacy have been published among patients on dialysis or patients with CKD and pain.38 In addition, patients on dialysis with pain should be assessed for the presence of coexisting diagnoses, such as depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders, because pain is often linked to these conditions.6,8,10,39 Perception of pain can be intensified by depression and anxiety, both of which occur frequently in patients with ESRD.10,12,38,39 These may be responsive to both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies, such as antidepressants or CBT, which may not be considered typical interventions for pain. Treatment addressing these conditions may ameliorate perceived pain. These approaches as well as other interventions directed at improving outcomes in patients on dialysis in pain, receiving opioid prescriptions, or addicted to opioids deserve consideration.

Retrospective analyses do not allow distinction between whether these medications are used in patients at high mortality risk or with terminal conditions and whether these medications may actually contribute to increased risk of death. Pain itself rather than or in addition to the prescription of medication may be in the causal pathway of mortality.6 Previous work showed that pain perceived in the nondialysis setting rather than during treatment itself was significantly associated with increased mortality in a single-center study of patients on HD.6

Our study was limited to those patients with full Part A, B, and D coverage. To the extent that prescription rates and outcomes are different in the remaining dialysis population, our results may not be fully applicable to the universe of patients on dialysis. Only filled prescriptions and not actual use or consumption of opioids were assessed in this study. The observational and retrospective nature of this analysis establishes associations only, not causation. Findings of increased mortality among patients prescribed opioids could be related to their use in patients with preexisting higher risk, although these associations persisted despite adjustment for comorbid conditions and other factors known to be associated with mortality. Retrospective studies are subject to biases, which may be limited by new user analyses. We do not know the cause of death of the patients in this study.

Furthermore, opioid prescription is not equivalent to addiction, and for many patients in the study, such prescription may be appropriate. Subclassification, therefore, probably exists for the patients in the study but cannot be delineated from the available data, and it remains an area for further research. Physicians, including nephrologists, should exercise caution in such prescription, engaging in discussions with patients as prescription of opioids is initiated and maintained.

In summary, we report high rates of both chronic opioid prescription and excessive dosing in the maintenance dialysis population. The most commonly used agents are associated with increased risk of mortality, hospitalization, and discontinuation of dialysis, although a causal role cannot be established. A dose-response relationship exists between the magnitude of prescribed medications in MME and adverse outcomes. The most commonly used opioids in this population are not consistent with analgesic agents recommended for this use in patients on dialysis on the basis of dosing and avoidance of toxicity.29 In fact, the most commonly used agent, hydrocodone, should have limited use in this population.29 Opioid prescriptions, especially in this population, where pain can have very specific, dialysis-related causes, should not be considered synonymous with treatment of pain.

To the extent that opioid drugs may cause death in patients on dialysis, appropriate clinical interventions to reduce drug prescription, dose level, and addiction, while keeping in mind patient satisfaction and comfort, are warranted. Nonpharmacologic therapies for pain control and approaches that minimize drug doses and duration of therapy deserve further study in this population, because they may result in lower patient mortality and morbidity.

Concise Methods

Study Design, Data Sources, and Sample Selection

Using standard USRDS analysis files, we performed a retrospective cohort study to (1) describe trends in the proportions of patients on dialysis who received chronic prescription of opioid medications overall and for specific opioids from 2006 to 2010; (2) examine factors associated with chronic opioid prescription in 2010 prevalent patients on dialysis; and (3) examine associations of all-cause death, discontinuation of dialysis, and hospitalization with short-term or chronic prescription of opioid overall and associated with dose prescribed and specific opioids in 2010 prevalent patients on dialysis. We used the definition of chronic use of opioids as defined in the opioid literature—90 days or more of opioid prescription within a 365-day timeframe.22 We also conducted two sensitivity analyses using a new user design.40,41

We first identified an annual cohort of adult patients ≥20 years old who resided in one of 50 states or Washington, DC and were not under hospice care (identified through claims listing place of service as hospice). To calculate opioid use comparable with the established literature, the cohorts were limited to full-year patients on dialysis, continuously treated with dialysis, with Medicare as their primary payer and full Part A, B, and D coverage (i.e., at least 365 days of enrollment) in each study year. The selection of patients on dialysis in year 2010 is illustrated in Figure 1. The same criteria were used to identify patients in other study years.

Study Measures

For each patient, Part D prescription claims data were used to determine whether a patient had ever received a prescription for an opioid (Supplemental Table 6) or an analgesic medication (Supplemental Table 7) and the days’ supply for each prescription obtained from an outpatient pharmacy during a given calendar year. The total days’ supply per year is the sum of the days’ supply for all of the patient’s opioid prescriptions during the year, regardless of whether the dates of the prescriptions overlapped or continued. We identified patients as having a chronic opioid prescription if the total supply for a study year was 90 days or more, having a short-term opioid prescription if the total supply for the year was 1–89 days, and a nonuser if the total days’ supply for the year was zero, consistent with previous definitions of chronicity.22 We also calculated the MME dosage for each opioid prescription using established conversion tables.42,43 We included overlapping opioid prescriptions per day and calculated a daily MME by distributing the total MME for all opioid prescriptions over the days supplied.

We did not have information regarding the indication for which an opioid was prescribed. We also summed the total gross drug cost of opioid prescriptions, including the ingredient cost, the dispensing fee, and the sales tax, if any, in each study year.44

In this analysis, Medicare inpatient billing data were used to identify (1) patients’ diagnosis of cancer, (2) whether they had at least one pain-related hospitalization, and (3) the number of hospitalizations in each calendar year. Indicator variables were set for patients with at least one hospitalization for cancer and at least one hospitalization with a pain diagnosis. (Supplemental Table 8 provides the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes used to identify cancer and pain-related diagnoses in Medicare claims.) Patients’ total numbers of hospitalizations in each study year were counted. We placed all patients having no hospitalization into one category and assigned the other patients to one of three other categories (one or two, three or four, or five or more hospital admissions).

Medicare physician/supplier billing data were used to indicate whether a patient resided in a nursing home. Nursing home residents were identified with at least one physician claim with the place of service listed as nursing home.

We assigned patients dual status, an individual level indicator of poverty, if they received dual insurance coverage by Medicare and Medicaid in Medicare Part A, B, or D for at least 1 month in each study year.45 We also flagged patients’ kidney transplantation status before January 1, 2010 (ever or never) and dialysis modality on January 1, 2011 (HD or PD) for the 2010 prevalent dialysis cohort.

Patient characteristics were taken from the CMS Medical Evidence Form (CMS Form 2728), including self-reported sex, race (black, white, or other), and smoking status at ESRD treatment initiation, as well as comorbid conditions.46 Patient age was calculated as of January 1 of each relevant year and summarized into three groups (20–44, 45–64, or ≤65 years old). On the basis of year of ESRD treatment initiation, patients’ vintage for ESRD treatment for each year was also assigned47 and categorized into three groups (1–2, 3–4, or 5 or more years). Using county of residence, we categorized type of residential area into large central/fringe metropolitan, medium/small metropolitan, and nonmetropolitan (i.e., rural) using the National Center for Health Statistics Urban–Rural Classification Scheme for counties.48

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest were all-cause death, discontinuation of dialysis, and incident hospitalization on or after January 1, 2011 for the 2010 prevalent dialysis cohort.

The 2010 prevalent patients on dialysis were followed from January 1, 2011 for all-cause death and censored at the earliest date of kidney transplantation, kidney function recovery, discontinuation of dialysis, loss to follow-up, or December 31, 2012. Patients were also followed for discontinuation of dialysis, censoring for kidney transplantation, kidney function recovery, loss to follow-up, death, or December 31, 2012. The third outcome was first hospitalization, censoring for kidney transplantation, kidney function recovery, discontinuation of dialysis, loss to follow-up, death, or December 31, 2012.

Statistical Analyses

We counted the number of patients on dialysis continuously treated with dialysis who had full Medicare Part A, B, and D coverage in each study year and calculated annual percentage distributions for age group, sex, race, dialysis modality, previous history of kidney transplantation, dual status, residential area, ESRD vintage, nursing home residence, cancer status, pain-related hospitalization, and number of hospitalizations in 2006–2010 prevalent patients on dialysis. The annual proportions of patients on dialysis with chronic opioid prescriptions, overall and for specific opioids as well as for specific ranges of MME, during 2006–2010 were also determined.

Descriptive statistics were used to depict demographic characteristics, age, ESRD vintage, dialysis modality, history of kidney transplantation, hospitalization status in 2010, and status of comorbid diseases for the 2010 prevalent dialysis cohort as a whole, by status of overall opioid prescription (none, short term, or chronic), and by MME. Percentage distributions were presented, and chi-squared tests were used to compare distribution differences overall and between opioid prescription groups.

A logistic regression model was used to identify factors associated with chronic prescription of any opioid medication, and Cox proportional hazards regression models were specified to examine the association of opioid prescription in 2010, overall, for specific opioids, and by MME, with subsequent all-cause death, discontinuation of dialysis, and hospitalization in the 2010 prevalent dialysis cohort. Separate proportional hazards regression models were conducted as a sensitivity analysis to examine the association of overall opioid prescription in 2010 with subsequent all-cause death, discontinuation of dialysis, and hospitalization in 2010 prevalent patients on HD and prevalent patients on PD (Supplemental Tables 9–11).

A subpopulation of the 2010 dialysis cohort, which included patients on dialysis without any filled opioid prescription from July 1, 2009 to Dec 31, 2009, was used to examine the associations of short-term or chronic opioid prescription with the outcomes of interest (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

Another subpopulation of the 2010 dialysis cohort, which included patients on dialysis without any filled opioid or analgesic prescription from July 1, 2009 to December 31, 2009, was used. We identified patients’ first prescription of an opioid or an analgesic in 2010 and followed them from the filled date of the prescription for all-cause death, discontinued dialysis, and first hospitalization to examine the association of the new use of an opioid or analgesic with those outcomes (Supplemental Tables 4 and 5).

All patient-level demographic characteristics and medical conditions were included in multivariate-adjusted models. Proportional hazards assumptions were examined by graphing log(−log[survival function]) curves. No violation was observed. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05 using two-tailed tests. For three-pair multiple comparisons, the Bonferroni method was used to define a statistically significant difference at P<0.017 using two-tailed tests. All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

C.-W.F. is supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases contract HHSN276201200161U.

Interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, or the US Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Prescription Opioids for Pain Management in Patients on Dialysis,” on pages 3432–3434.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2017010098/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Binik YM, Baker AG, Kalogeropoulos D, Devins GM, Guttmann RD, Hollomby DJ, Barré PE, Hutchison T, Prud’Homme M, McMullen L: Pain, control over treatment, and compliance in dialysis and transplant patients. Kidney Int 21: 840–848, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raghavan D, Holley JL: Conservative care of the elderly CKD patient: A practical guide. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 23: 51–56, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davison SN: Pain in hemodialysis patients: Prevalence, cause, severity, and management. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 1239–1247, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santoro D, Satta E, Messina S, Costantino G, Savica V, Bellinghieri G: Pain in end-stage renal disease: A frequent and neglected clinical problem. Clin Nephrol 79[Suppl 1]: S2–S11, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shayamsunder AK, Patel SS, Jain V, Peterson RA, Kimmel PL: Sleepiness, sleeplessness, and pain in end-stage renal disease: Distressing symptoms for patients. Semin Dial 18: 109–118, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris TJ, Nazir R, Khetpal P, Peterson RA, Chava P, Patel SS, Kimmel PL: Pain, sleep disturbance and survival in hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 758–765, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen SD, Patel SS, Khetpal P, Peterson RA, Kimmel PL: Pain, sleep disturbance, and quality of life in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 919–925, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davison SN: Chronic kidney disease: Psychosocial impact of chronic pain. Geriatrics 62: 17–23, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davison SN, Jhangri GS: Impact of pain and symptom burden on the health-related quality of life of hemodialysis patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 39: 477–485, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davison SN, Jhangri GS: The impact of chronic pain on depression, sleep, and the desire to withdraw from dialysis in hemodialysis patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 30: 465–473, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garland EL: Treating chronic pain: The need for non-opioid options. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 7: 545–550, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheatle MD: Biopsychosocial approach to assessing and managing patients with chronic pain. Med Clin North Am 100: 43–53, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barakzoy AS, Moss AH: Efficacy of the world health organization analgesic ladder to treat pain in end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3198–3203, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Claxton RN, Blackhall L, Weisbord SD, Holley JL: Undertreatment of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 39: 211–218, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davison SN, Mayo PR: Pain management in chronic kidney disease: The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of hydromorphone and hydromorphone-3-glucuronide in hemodialysis patients. J Opioid Manag 4: 335–344, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davison SN, Koncicki H, Brennan F: Pain in chronic kidney disease: A scoping review. Semin Dial 27: 188–204, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merboth MK, Barnason S: Managing pain: The fifth vital sign. Nurs Clin North Am 35: 375–383, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R: CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 65: 1–49, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joranson DE, Ryan KM, Gilson AM, Dahl JL: Trends in medical use and abuse of opioid analgesics. JAMA 283: 1710–1714, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuehn BM: Opioid prescriptions soar: Increase in legitimate use as well as abuse. JAMA 297: 249–251, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkerson RG, Kim HK, Windsor TA, Mareiniss DP: The opioid epidemic in the United States. Emerg Med Clin North Am 34: e1–e23, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuo YF, Raji MA, Chen NW, Hasan H, Goodwin JS: Trends in opioid prescriptions among part D medicare recipients from 2007 to 2012. Am J Med 129: 221.e21–221.e30, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inocencio TJ, Carroll NV, Read EJ, Holdford DA: The economic burden of opioid-related poisoning in the United States. Pain Med 14: 1534–1547, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olivo RE, Hensley RL, Lewis JB, Saha S: Opioid use in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 1103–1105, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butler AM, Kshirsagar AV, Brookhart MA: Opioid use in the US hemodialysis population. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 171–173, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elzey MJ, Barden SM, Edwards ES: Patient characteristics and outcomes in unintentional, non-fatal prescription opioid overdoses: A systematic review. Pain Physician 19: 215–228, 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calcaterra SL, Yamashita TE, Min SJ, Keniston A, Frank JW, Binswanger IA: Opioid prescribing at hospital discharge contributes to chronic opioid use. J Gen Intern Med 31: 478–485, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kern DM, Zhou S, Chavoshi S, Tunceli O, Sostek M, Singer J, LoCasale RJ: Treatment patterns, healthcare utilization, and costs of chronic opioid treatment for non-cancer pain in the United States. Am J Manag Care 21: e222–e234, 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koncicki HM, Brennan F, Vinen K, Davison SN: An approach to pain management in end stage renal disease: Considerations for general management and intradialytic symptoms. Semin Dial 28: 384–391, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB: Opioid-prescribing patterns of emergency physicians and risk of long-term use. N Engl J Med 376: 663–673, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM: Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA 315: 2415–2423, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veilleux JC, Colvin PJ, Anderson J, York C, Heinz AJ: A review of opioid dependence treatment: Pharmacological and psychosocial interventions to treat opioid addiction. Clin Psychol Rev 30: 155–166, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henrich WL, Agodoa LE, Barrett B, Bennett WM, Blantz RC, Buckalew VM Jr., D’Agati VD, DeBroe ME, Duggin GG, Eknoyan G: Analgesics and the kidney: Summary and recommendations to the scientific advisory board of the national kidney foundation from an Ad Hoc committee of the national kidney foundation. Am J Kidney Dis 27: 162–165, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss RD, Potter JS, Griffin ML, Provost SE, Fitzmaurice GM, McDermott KA, Srisarajivakul EN, Dodd DR, Dreifuss JA, McHugh RK, Carroll KM: Long-term outcomes from the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network Prescription Opioid Addiction Treatment Study. Drug Alcohol Depend 150: 112–119, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee JD, Friedmann PD, Kinlock TW, Nunes EV, Boney TY, Hoskinson RA Jr., Wilson D, McDonald R, Rotrosen J, Gourevitch MN, Gordon M, Fishman M, Chen DT, Bonnie RJ, Cornish JW, Murphy SM, O’Brien CP: Extended-release naltrexone to prevent opioid relapse in criminal justice offenders. N Engl J Med 374: 1232–1242, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castro MM, Daltro C, Kraychete DC, Lopes J: The cognitive behavioral therapy causes an improvement in quality of life in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 70: 864–868, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pigeon WR, Moynihan J, Matteson-Rusby S, Jungquist CR, Xia Y, Tu X, Perlis ML: Comparative effectiveness of CBT interventions for co-morbid chronic pain & insomnia: A pilot study. Behav Res Ther 50: 685–689, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cukor D, Ver Halen N, Asher DR, Coplan JD, Weedon J, Wyka KE, Saggi SJ, Kimmel PL: Psychosocial intervention improves depression, quality of life, and fluid adherence in hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 196–206, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kimmel PL: The weather and quality of life in ESRD patients: Everybody talks about it, but does anybody do anything about it? Semin Dial 26: 260–262, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ray WA: Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: New-user designs. Am J Epidemiol 158: 915–920, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell CI, Weisner C, Leresche L, Ray GT, Saunders K, Sullivan MD, Banta-Green CJ, Merrill JO, Silverberg MJ, Boudreau D, Satre DD, Von Korff M: Age and gender trends in long-term opioid analgesic use for noncancer pain. Am J Public Health 100: 2541–2547, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Opioid Morphine Equivalent Conversion Factors, 2014. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Opioid-Morphine-EQ-Conversion-Factors-March-2015.pdf. Accessed December 13, 2016

- 43.Von Korff M, Saunders K, Thomas Ray G, Boudreau D, Campbell C, Merrill J, Sullivan MD, Rutter CM, Silverberg MJ, Banta-Green C, Weisner C: De facto long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain. Clin J Pain 24: 521–527, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chronic Condition Data Warehouse: Medicare Part D Event (PDE) codebook, 2016. Available at: https://www.ccwdata.org/cs/groups/public/documents/datadictionary/tot_rx_cst_amt.txt. Accessed June 21, 2016

- 45.Kimmel PL, Fwu CW, Abbott KC, Ratner J, Eggers PW: Racial disparities in poverty account for mortality differences in US medicare beneficiaries. SSM Popul Health 2: 123–129, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kimmel PL, Fwu CW, Eggers PW: Segregation, income disparities, and survival in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 293–301, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garg JP, Chasan-Taber S, Blair A, Plone M, Bommer J, Raggi P, Chertow GM: Effects of sevelamer and calcium-based phosphate binders on uric acid concentrations in patients undergoing hemodialysis: A randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum 52: 290–295, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ingram DD, Franco SJ: NCHS urban-rural classification scheme for counties. Vital Health Stat 2 154: 1–65, 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.