Abstract

Previous research has shown that acute nicotine, an agonist of nAChRs, impaired fear extinction. However, the effects of acute nicotine on consolidation of contextual fear extinction memories and associated cell signaling cascades are unknown. Therefore, we examined the effects of acute nicotine injections before (pre-extinction) and after (post-extinction) contextual fear extinction on behavior and the phosphorylation of dorsal and ventral hippocampal ERK1/2 and JNK1 and protein levels on the 1st and 3rd day of extinction. Our results showed that acute nicotine administered prior to extinction sessions downregulated the phosphorylated forms of ERK1/2 in the ventral hippocampus, but not dorsal hippocampus, and JNK1 in both dorsal and ventral hippocampus on the 3rd extinction day. These effects were absent on the 1st day of extinction. We also showed that acute nicotine administered immediately and 30 mins, but not 6 hours, following extinction impaired contextual fear extinction suggesting that acute nicotine disrupts consolidation of contextual fear extinction memories. Finally, acute nicotine injections immediately after extinction sessions upregulated the phosphorylated forms of ERK1/2 in the ventral hippocampus, but did not affect JNK1. These results show that acute nicotine impairs contextual fear extinction potentially by altering molecular processes responsible for the consolidation of extinction memories.

Keywords: Nicotine, Hippocampus, Extinction, ERK1/2, JNK1

1. Introduction

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) regulate a variety of cell signaling cascades that are important for various behavioral processes such as long-term memory formation (see Kutlu & Gould, 2016 for a review). In the hippocampus, nAChRs gate calcium (Ca2+) and sodium into the cell (Wonnacott, 1997). By modulating Ca2+ influx, activation of nAChRs leads to activation of hippocampal cell signaling cascades through the increase in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and phosphorylation of various kinases, including kinases within the family of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs; Dajas-Bailador et al., 2002; Nuutinen et al., 2007). For example, nicotine, an agonist of nAChRs, has been shown to alter the phosphorylation state of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2; Valjent et al., 2004; Neugebauer et al., 2011; Gould et al., 2014). Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in the hippocampus is required for long-term potentiation (LTP; Winder et al., 1999; Coogan et al., 1999), a process that may underlie long-term memory formation (Bliss & Collingridge, 1993), and consolidation of fear memories (Trifilieff et al., 2006). Importantly, Gould et al. (2014) showed that acute nicotine administration prior to contextual fear conditioning shifted the learning-associated ERK1/2 activity in the hippocampus and enhanced hippocampus-dependent fear learning. This suggests that nicotine may enhance consolidation of fear memories by altering phosphorylation patterns of hippocampal ERK1/2.

Another MAPK family kinase that plays an important role in long-term memory formation is c-jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1). Although JNK1 seems to have a minimal role in baseline LTP (Li et al., 2007), there is evidence showing that JNK1 is required for hippocampal long-term depression (LTD; Li et al., 2007; Curran et al., 2003), a process responsible for the reversal of LTP. In addition, Leach et al. (2015) showed that JNK1 knockout (KO) mice, under baseline conditions, expressed similar levels of contextual fear conditioning as wild-type (WT) littermates, but unlike WT mice, KO mice did not show stronger learning with an increased number of training trials. This suggests JNK1 may modulate the strength of memories. There is also evidence from our lab showing that hippocampal JNK1 phosphorylation is required for the acute nicotine-induced enhancement of contextual fear conditioning (Kenney et al., 2010; Leach et al., 2016). For example, acute nicotine upregulated the JNK1 mRNA in the hippocampus during the nicotine enhancement of contextual fear conditioning (Kenney et al., 2010). Moreover, the acute nicotine-induced enhancement of contextual fear conditioning was absent in JNK1 KO mice (Leach et al., 2016). These results show that JNK1 may be critical for the nicotinic modulation of long-term memory formation.

In contrast to the enhancing effects of acute nicotine on contextual fear conditioning, we recently showed that acute nicotine administered prior to extinction impaired contextual fear extinction (Kutlu & Gould, 2014) and this effect was dependent on high-affinity α4β2 nAChRs (Kutlu et al., 2016a). Fear extinction is a process whereby new inhibitory memories are created, which results in a reduction of learned responses (Myers & Davis, 2007). Both hippocampal LTP (de Carvalho et al., 2012) and LTD (Lin et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2007; Dalton et al., 2008; 2012) have been implicated in successful extinction learning. In addition, ERK1/2 and JNK1 have been shown to play important roles in LTP and LTD, respectively. Accordingly, there is evidence showing that both ERK1/2 and JNK1 are also necessary for extinction learning (Bevilaqua et al., 2007; Fischer et al., 2007; Matsuda et al., 2010). Therefore, one possibility is that ERK1/2 and JNK1 modulate consolidation of extinction memories by mediating plasticity similar to that measured with LTP and LTD.

Our results showing that nicotine administered prior to each extinction session impaired contextual fear extinction suggest that nicotine may alter encoding of extinction memories. However, processes triggered by nicotine may still be active when encoding of extinction memories transitions to consolidation after the extinction session ends. Therefore, it is not clear if the impairment of contextual extinction is a result of disrupted encoding or consolidation of long-term extinction memories. Moreover, the effects of acute nicotine on hippocampal kinases-associated memory consolidation processes during contextual fear extinction are unknown. In the present study, we investigated the effects of acute nicotine administration prior and immediately following each extinction session on hippocampal levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 and JNK1. Second, in order to test our hypothesis that acute nicotine alters memory consolidation processes, we examined the effects of acute nicotine on consolidation of extinction memories by administering nicotine within and outside the memory consolidation window, a 6 hr temporal window where newly acquired memories are stabilized into long-term memory storage (Dudai, 2004; Katche et al., 2013). Given that our previous studies showed that the dorsal hippocampus (dHPC) mainly controlled the effects of nicotine on fear acquisition (Kenney et al., 2010; Gould et al., 2014) whereas the ventral hippocampus (vHPC) mainly modulated the effects of nicotine on contextual fear extinction (Kutlu et al. 2016b), we investigated these two sub-regions separately.

Therefore, we examined the effects of acute nicotine injections before (pre-extinction) and after (post-extinction) contextual fear extinction on behavior and the phosphorylation of dorsal and ventral hippocampal ERK1/2 and JNK1 and protein levels on the 1st and 3rd day of extinction. Our results showed that acute nicotine administered prior to extinction sessions downregulated the phosphorylated forms of ERK1/2 in the ventral hippocampus, but not dorsal hippocampus, and JNK1 in both dorsal and ventral hippocampus on the 3rd extinction day. These effects were absent on the 1st day of extinction. We also showed that acute nicotine administered immediately and 30 mins, but not 6 hours, following extinction impaired contextual fear extinction suggesting that acute nicotine disrupts consolidation of contextual fear extinction memories. Finally, acute nicotine injections immediately after extinction sessions upregulated the phosphorylated forms of ERK1/2 in the ventral hippocampus, but did not affect JNK1.

2. Method

Subjects

Subjects were adult male C57BL/6J mice (8-10 weeks old, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) that were group-housed and maintained in a 12 h light/dark cycle. All mice had access to food and water ad-libitum. Mice were given a week of acclimation when they arrived at our animal colony. In addition, mice were tagged with a marking solution 24 hours prior to training. Training and retention test occurred between 9:00 am and 7:00 pm. Behavioral procedures used in this study were approved by the Temple University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Apparatus

All behavioral experiments took place in four identical chambers (18.8 × 20 × 18.3 cm), which were composed of Plexiglas and placed in sound attenuating boxes (MED Associates). Ventilation fans that produced a background noise (65 dB) were mounted in the back of each behavioral chamber. The chamber floors were metal grids (0.20 cm in diameter and 1.0 cm apart) connected to a shock generator. The stimuli were controlled by an IBM-PC compatible computer running MED-PC software.

Drug

For the initial behavioral experiments, nicotine hydrogen tartrate salt (0.18 mg/kg freebase, Sigma) dissolved in 0.9% physiological saline (saline) or saline alone was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) immediately, 30 mins, or 6 hrs following each extinction session. Injection volumes were 10 mL/kg as in previous studies (e.g., Kutlu & Gould 2014). The 0.18 mg/kg dose of acute nicotine was chosen based on our previous reports showing impaired contextual fear extinction at this dose (Kutlu & Gould, 2014; Kutlu et al., 2016a). For the subsequent western blotting experiments, the same dose of nicotine or saline was administered i.p. 2–4 min prior to each extinction session for “pre-extinction” experiments; whereas nicotine was administered immediately after each extinction session for the “post-extinction” experiments.

Behavioral procedures

Freezing behavior, which was defined as the absence of voluntary movement except respiration (Davis et al, 2005), was employed as the dependent variable. A time sampling method was used in which subjects were observed every 10 s for 1 s and scored as active or freezing. Subjects were trained in contextual fear conditioning. Specifically, mice were placed in the fear conditioning chambers and following a 120 sec baseline period, they received 2 conditioned stimulus (CS, 30-sec white noise, 85 dB)-unconditioned stimulus (US; a 2-sec, 0.57-mA foot-shock) pairings wherein the CS and the US co-terminated. Twenty-four hours later mice were re-introduced to the fear conditioning chambers to assess for their freezing responses to the context (Retention Test). The duration for both fear conditioning and the retention test was 5 minutes and 30 seconds. For the next 5 days, mice were given contextual fear extinction where they were placed in the chambers for 5 mins and their freezing behavior was scored. For the behavioral experiments examining the effects of acute nicotine on consolidation of contextual fear extinction, injections were administered immediately, 30 mins, or 6 hrs after each extinction session starting from the retention test. These time points were chosen as immediate injections and injections at 30 min time-point would lay within the memory consolidation window whereas injections at 6 hrs time-point would lay outside the consolidation window and serve as a control (Dudai, 2004; Katche et al., 2013).

Western blotting

For the initial western blotting experiments, mice were given saline or nicotine (0.18 mg/kg) injections prior to each extinction session. Either after the 1st or 3rd extinction session, mice were sacrificed through cervical dislocation at the 1hr post-training time-point and hippocampi were dissected into dorsal and ventral sections (in a 1:1 ratio) and frozen on dry ice. In addition, another group of mice that were trained in contextual fear extinction but received acute nicotine immediately following each extinction session were sacrificed at the 1hr post-training time-point and hippocampi were dissected as described above. The dissection time point was chosen based on a previous report from our laboratory examining acute nicotine’s effects on ERK1/2 phosphorylation during contextual fear conditioning (Gould et al., 2014). We examined ERK1/2 and JNK1 activation at the end of the 1st and 3rd extinction day based on our previous studies showing that the effect of nicotine is the largest on the 3rd day of extinction as the saline group usually shows complete extinction by that day (Kutlu & Gould, 2014; Kutlu et al., 2016a). Therefore, the 1st extinction day analysis served as a control as we did not expect to see a large difference in terms of long-term memory-associated kinase activity. Then dorsal and ventral hippocampi were homogenized using a sonic dismembrator (Fisher Scientific) in RIPA buffer (Sigma) containing 1X HALT Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific). The total protein concentration for each sample was determined using DC ™ Protein Assay (Bio-Rad) and samples were diluted with RIPA buffer to obtain 15μg of total protein. Then each sample was diluted 1:1 with Laemmeli sample buffer (Bio-Rad) containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol and loaded into TGX 4 20% gradient gels (Bio-Rad). Proteins were separated via electrophoresis conducted at 100 V constant voltage for 80 min in 1X Tris–Glycine-SDS running buffer (Bio-Rad) then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) for 2 h at 400 mA constant current in ice-cold 1X Tris–Glycine buffer (Bio-Rad) containing 20% methanol. Following transfer, membranes were washed with tris buffered saline (TBS) and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; fraction V, Omnipur) in 1X TBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature. Then membranes were incubated in primary antibodies (anti-phospho-ERK1/2 rabbit mAb, Cell Signaling, 1:2,000; anti-ERK1/2 rabbit mAb, Cell Signaling, 1:2,000; anti-phospho-JNK1 rabbit pAb, Promega, 1:5,000; anti-JNK1/JNK2 mouse mAb, BD Biosciences, 1:1,000; anti-β-Actin mouse mAb, Sigma–Aldrich, 1:5,000; anti-β-Tubulin mouse mAb, Sigma–Aldrich, 1:20,000) in 5% BSA overnight at 4°C. The next day, blots were incubated in HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories, anti-rabbit, 1:2,000 for pERK1/2 and tERK1/2, 1:1,000 for pJNK1, and anti-mouse, 1:1,000 for JNK1/JNK2; 1:10,000 for β -actin, 1:40,000 for β-Tubulin in 5%BSA) for 1hr in room temperature and enhanced chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate; Thermo Scientific) was applied for 5 mins. Blots were imaged using a single 60 s exposure on a Kodak camera (Gel Logic 1500 Imaging System) and bands were quantified as optical density values of target bands using ImageJ software. Levels of phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK) were first normalized to total ERK1/2 (tERK) protein levels and then to β-actin loading control protein levels for final quantification. Levels of phospho-JNK1 (pJNK1) were first normalized to total JNK (tJNK; JNK1/JNK2) protein levels and then to β-Tubulin loading control protein levels for final quantification

Statistical Analysis

For the consolidation behavioral experiments, freezing response during extinction sessions was normalized to the initial freezing response measured during the retention test (freezing × 100/ initial freezing) following previous studies from our lab and others reporting the effects of nicotine on contextual fear extinction (Tian et al., 2008; Kutlu et al., 2016a). This way we eliminated potential between-group baseline differences in contextual freezing, which may affect subsequent fear extinction curves. Separate 2-way repeated measures ANOVAs (Drug [Nicotine, Saline] × Trial [Retention test and 5 extinction session]) were used to analyze the normalized freezing scores for each injection time point (immediately, 30 mins, 6 hrs). We used Bonferroni-corrected t-tests to compare normalized freezing levels between drug groups for each extinction session. For the western blotting experiments, the optical density values from western blot experiments were represented as fold-changes relative to the respective saline control group and analyzed using one-way ANOVAs for each brain region. One mouse from the Immediate/Saline, 1 mouse from the 30mins/Saline, 1 mouse from the 6hrs/Saline were removed from analysis as their average normalized freezing levels across 5 extinction sessions were 2 standard deviations above the group means. Similarly, data of 1 subject from the pre-extinction ERK saline group, 1 subjects from the post-extinction ERK saline group, 1 subject from the post-extinction ERK nicotine group, 1 subject from the post-extinction JNK saline group, and 1 subject from the post-extinction JNK nicotine group were removed from analysis as their pERK/tERK or pJNK1/tJNK fold change values were higher than 2 standard deviations above the group mean. Group sizes were indicated in figure captions. All statistical analyses were run using SPSS 21.

3. Results

Acute nicotine administration prior to contextual fear extinction downregulates hippocampal pERK1/2 and pJNK1 levels

First, we examined the protein levels of hippocampal ERK1/2 and JNK1 during contextual fear extinction following pre-extinction saline or nicotine administration. Tissue from mice that received contextual fear conditioning were collected at 1hr after the 1st or 3rd day of extinction. Two separate repeated measure ANOVAs that assessed normalized percent freezing showed that Drug × Trial interaction was not significant for the group that received only 1 contextual fear extinction session (Figure 1A; F(1,13)=2.665, p>0.05) but it was significant for the group that received 3 extinction sessions (Figure 1B; F(3,36)=3.681, p<0.05). Replicating our previous results (Kutlu & Gould, 2014; Kutlu et al., 2016), these results suggest that more than a single extinction session may be required to observe the impairing effects of acute nicotine on contextual fear extinction (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Acute nicotine injections prior to extinction sessions disrupt contextual fear extinction during the 3rd extinction day, but not 1st extinction day.

Panel A: Mice administered acute nicotine (0.18 mg/kg) did not show impaired contextual fear extinction during the 1st extinction day (n=7-8 per group). Panel B: Acute nicotine (0.18 mg/kg) administered mice showed impaired contextual fear extinction during the 2nd and 3rd extinction days (n=7 per group). Error bars indicate Standard Error of the Mean (SEM). (*) denotes significant differences between nicotine group and saline controls at the p<0.05 level.

With the ERK1/2 westerns, we found no drug group differences in the levels of housekeeping protein β-Actin (1st day, F(1,13)=0.057, p>0.05; 3rd day, F(1,12)=0.109, p>0.05). In addition, total protein levels of ERK1/2 (1st day, F(1,13)=0.374, p>0.05; 3rd day, F(1,12)=0.176, p>0.05) did not show any group differences when mice received nicotine prior to each extinction session. Separate one-way ANOVAs we ran for pERK/tERK levels showed that the main effect of Drug was not significant for either of the brain regions at the 1st extinction day (Figure 2A; F(1,13)=0.143, p>0.05 for dHPC; F(1,13)=0.107, p>0.05 for vHPC). The main effect of Drug was significant for vHPC at the 3rd extinction day (Figure 2B; F(1,12)=5.854, p<0.05) but not for dHPC (F(1,12)=1.443, p>0.05). These results show that acute nicotine downregulated the activated form of ERK1/2 levels in the ventral hippocampus at the 3rd day of extinction but not at the 1st day of extinction (Figure 2). Moreover, dHPC levels of pERK1/2 were not affected by the acute nicotine treatment at both the 1st and 3rd day of extinction.

Figure 2. Acute nicotine injections prior to extinction sessions downregulate the active form of ERK1/2 in the ventral hippocampus at the 3rd, but not 1st extinction day.

Panel A: Acute nicotine (0.18 mg/kg) administration prior to extinction did not have an effect on pERK/tERK ratio in dHPC and vHPC on the 1st extinction day (n=7-8 per group). Panel B: Acute nicotine (0.18 mg/kg) administration prior to extinction downregulated vHPC pERK/tERK ratio but did not have an effect on dHPC pERK/tERK ratio on the 3rd extinction day. Error bars indicate Standard Error of the Mean (SEM). (*) denotes significant differences between nicotine group and saline controls at the p<0.05 level.

For the JNK1 western blots, we found no effect of drug on the levels of housekeeping protein β-tubulin (1st day, F(1,13)=0.538, p>0.05; 3rd day, F(1,12)=1.286, p>0.05) or total protein levels of JNK1 (1st day, F(1,13)=0.086, p>0.05; 3rd day, F(1,12)=0.221, p>0.05). However, separate one-way ANOVAs on pJNK1/tJNK levels showed that although the main effect of Drug was not significant at the 1st extinction day (Figure 3A; F(1,13)=0.971, p>0.05 for dHPC; F(1,13)=0.198, p>0.05 for vHPC); it was significant for both dHPC and vHPC at the 3rd extinction day (Figure 3B; F(1,12)=6.475, p<0.05 for dHPC; F(1,12)=9.125, p<0.05 for vHPC). These results suggest that acute nicotine administration on the 3rd day of extinction downregulated both dHPC and vHPC levels of pJNK1 but not on the 1st day of extinction (Figure 3). Taken together, our results show that acute nicotine downregulates the activated form of ERK1/2 in vHPC and JNK1 in both dHPC and vPHC as it impairs contextual fear extinction. This suggests that acute nicotine-induced impairment of contextual fear extinction may be a result of disrupted consolidation of fear extinction memories.

Figure 3. Acute nicotine injections prior to extinction sessions downregulate the active form of JNK1 in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus at the 3rd, but not 1st extinction day.

Panel A: Acute nicotine (0.18 mg/kg) administration prior to extinction did not have an effect on pJNK1/tJNK ratio in dHPC and vHPC at the 1st extinction day (n=7-8 per group). Panel B: Acute nicotine (0.18 mg/kg) administration prior to extinction downregulated both dHPC and vHPC pJNK1/tJNK ratio at the 3rd extinction day. Error bars indicate Standard Error of the Mean (SEM). (*) denotes significant differences between nicotine group and saline controls at the p<0.05 level.

Acute nicotine administered following extinction sessions disrupts consolidation of contextual fear extinction memories

In order to examine if acute nicotine disrupts consolidation of extinction memories, we administered acute nicotine within the memory consolidation window (immediately or 30 mins after) or outside the window (6 hrs after) following contextual fear extinction. Separate 2-way repeated measures ANOVA found that Drug × Trial interaction was significant for the groups that received drug injections immediately (Figure 4A; F(5,80)=2.553, p<0.05) and 30 mins (Figure 4B; F(5,85)=3.470, p<0.05) after each extinction session, but not for the group that received injections 6 hrs after each extinction session (Figure 4C; F(5,65)=0.090, p>0.05). Bonferroni-corrected t-tests showed that the freezing levels were different between nicotine and saline groups during the 5th extinction session for the Immediate group and during the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th extinction sessions for the 30 min group (ps<0.05). These results suggest that when acute nicotine is administered immediately and 30 mins following extinction sessions, but not after 6 hrs, consolidation of contextual fear extinction is disrupted. We also found that there was a significant Injection Time × Trial interaction for the groups that received saline (Immediate, 30 mins, and 6 hrs; F(10,105)=1.922, p=0.050). Therefore, while receiving a saline injection immediately after extinction impaired the consolidation of extinction memory, the impairment produced by nicotine was more pronounced.

Figure 4. Acute nicotine administered following extinction sessions disrupts consolidation of contextual fear extinction memories.

Panel A: Acute nicotine (0.18 mg/kg) administered immediately following extinction sessions disrupted consolidation of contextual fear extinction in mice (n=8-10 per group). Panel B: Acute nicotine (0.18 mg/kg) administered 30 mins after extinction sessions disrupted consolidation of contextual fear extinction in mice (n=9-10 per group). Panel C: Acute nicotine (0.18 mg/kg) administered 6 hrs after extinction sessions had no effects on consolidation of contextual fear extinction in mice (n=7-8 per group). Error bars indicate Standard Error of the Mean (SEM). (*) denotes significant differences between nicotine group and saline controls at the p<0.05 level.

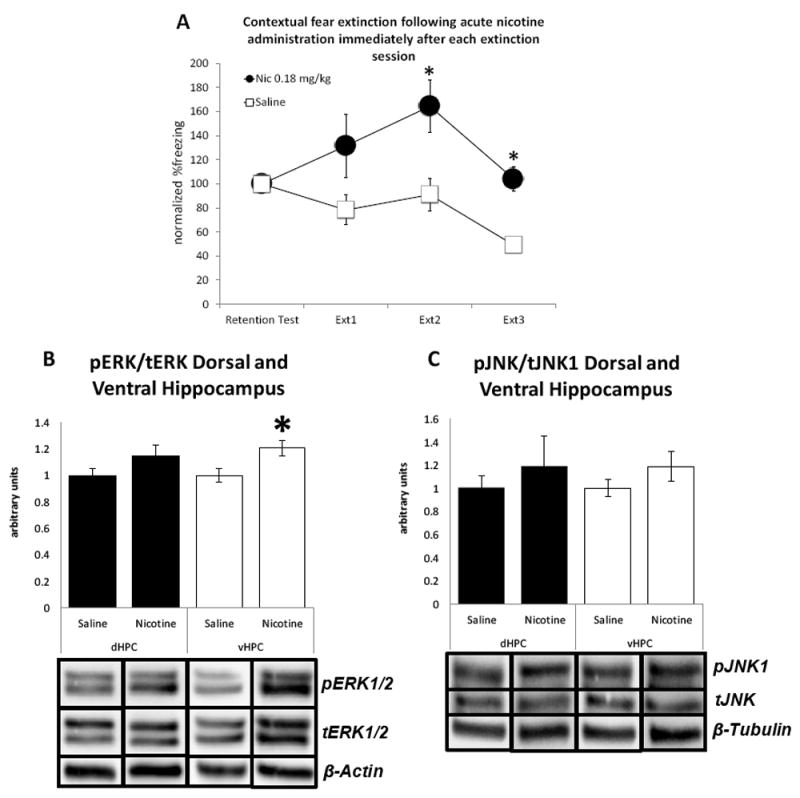

Acute nicotine administration immediately after contextual fear extinction upregulates ventral hippocampal pERK1/2 levels

We trained another group of mice that received acute nicotine (0.18 mg/kg) immediately following each extinction session to examine the effects of acute nicotine injections following extinction sessions and within the consolidation window on ERK1/2 and JNK1 levels. The behavioral results replicated the findings of our initial experiments showing injection of nicotine immediately following extinction sessions results in impaired consolidation of extinction memories (Figure 5A; Trial × Drug interaction F(3,39)=3.578, p<0.05). In addition, western blots on the tissue collected from this group of mice showed that post-extinction nicotine increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Separate one-way ANOVAs on pERK/tERK ratios showed that the main effect of Drug was significant for vHPC (Figure 5B; F(1,13)=8.239, p<0.05) but not for dHPC (F(1,13)=2.716, p>0.05). In contrast, separate one-way ANOVAs of the JNK1 western blots, showed that the main effect of Drug was not significant for dHPC (Figure 5C; F(1,13)=0.605, p>0.05) or vHPC (F(1,13)=2.031, p>0.05). We found no effects of post-extinction nicotine administration on β-Actin (F(1,13)=0.003, p>0.05) or β-Tubulin (F(1,13)=0.018, p>0.05) housekeeping proteins or total levels of ERK1/2 (F(1,13)=1.300, p>0.05) and JNK1 (F(1,13)=0.992, p>0.05). These results suggest that in contrast to pre-extinction injections, post-extinction nicotine injections increase phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in the ventral hippocampus but do not affect phosphorylation of JNK1.

Figure 5. Acute nicotine injections following extinction sessions upregulate the active form of ERK1/2 in the ventral hippocampus but have no effect on JNK1 phosphorylation.

Panel A: Acute nicotine (0.18 mg/kg) administered immediately following extinction sessions disrupted consolidation of contextual fear extinction in mice (n=7-8 per group). Panel B: Acute nicotine (0.18 mg/kg) administration following extinction sessions resulted in increased pERK/tERK ratio in the ventral, but not in dorsal, hippocampus (n=7-8 per group). Panel C: Acute nicotine (0.18 mg/kg) administration immediately following extinction sessions had no effect on pJNK1/tJNK ratio in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus (n=7-8 per group). Error bars indicate Standard Error of the Mean (SEM). (*) denotes significant differences between nicotine group and saline controls at the p<0.05 level.

4. Discussion

The results of the present study showed that contextual fear extinction was impaired when acute nicotine was administered within the memory consolidation window, immediately and 30 mins following extinction, but not outside the memory consolidation window, 6 hrs following extinction. Moreover, we found that nicotine administered prior to extinction sessions downregulated the phosphorylated forms of ERK1/2 in vHPC and JNK1 in both dHPC and vHPC during consolidation on the 3rd day of contextual fear extinction. No effects of nicotine were observed at the 1st day of extinction. Finally, we found that nicotine upregulated the active form of ERK1/2 in the vHPC when administered immediately after each extinction session but had no effect on pJNK1 levels. Overall, these results suggest that acute nicotine disrupts both encoding and consolidation of contextual extinction memories by differentially altering activation of hippocampal kinases that control or modulate long-term memory formation (Trifilieff et al., 2006; Leach et al., 2015).

Our results showing that acute nicotine impairs contextual fear extinction when administered immediately or 30 mins, but not 6 hrs, after each extinction session are in line with other reports showing that modulation of molecular substrate of learning and memory systems within this window results in alterations in memory consolidation (e.g., Schafe & LeDoux, 2000; Fricks-Gleason et al., 2012; Peters & De Vries, 2013). It is important to note that these effects are not likely to be due to any aversive effects of nicotine itself. In a recent study, we demonstrated that the dose of nicotine we used (0.18 mg/kg) did not induce freezing when administered in the absence of the footshock or result in decreased levels of activity (Kutlu et al., 2016a). Similarly, we also showed that when mice received exposure to a novel context following fear conditioning, nicotine administration did not increase freezing behavior in that novel context (Kutlu & Gould, 2014). Therefore, there is strong evidence suggesting that nicotine administration immediately following extinction sessions has a specific effect on extinction memory consolidation and not on peripheral processes that could alter freezing. Finally, our behavioral results showed that saline injections within the memory consolidation window also impaired contextual fear extinction; however, the effect was small. It has been repeatedly shown that stress and anxiety impair fear extinction (Miracle et al., 2006; Izquierdo et al., 2006; Yamamato et al., 2008; Akirav et al., 2009) as well as long-term memory consolidation (Park et al., 2008). Therefore, one possibility is that stress resulting from i.p. injections interfered with the memory consolidation process but nonetheless, the effects of nicotine were significantly greater than the control injections.

In line with the potential effects of acute nicotine on the consolidation of contextual fear extinction memories, our results also showed that the acute nicotine-induced impairment of contextual fear extinction was associated with altered levels of phosphorylated kinases involved in memory formation and hippocampal plasticity. These results are in line with previous results suggesting that ERK1/2 and JNK1 play important roles during LTP/LTD (Lin et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2007; Dalton et al., 2008; 2012; de Carvalho et al., 2013) and fear extinction (Bevilaqua et al., 2007; Fischer et al., 2007; Matsuda et al., 2010). Interestingly, we found that while pre-extinction nicotine administration resulted in downregulation of ventral hippocampal pERK1/2 as well as dorsal and ventral hippocampal pJNK1 levels, post-extinction injections resulted in upregulated levels of ventral hippocampal pERK1/2 but had no effects on pJNK1. These results suggest that although pre- and post-extinction nicotine administration lead to the same behavioral phenotype (i.e., impaired extinction), the underlying mechanisms are different.

One possible explanation for the differences in the effects of nicotine on cell signaling during extinction is that nicotine alteration of pERK1/2 and pJNK1 levels depends on the stage of extinction process at the time of administration. For example, Antoine et al. (2014) showed that when contextual fear is recalled in extinction, hippocampal pERK1/2 levels first increase during the session and gradually decrease at 15, 30, and 60 min post-session time points. It is important to note that shifting the temporal pattern of ERK1/2 activation during memory consolidation can alter long-term memory formation (Gould et al., 2014). This suggests that pre- and post-extinction nicotine injections may also shift the timing of ERK1/2 phosphorylation and disrupt consolidation of extinction memories. Our results also demonstrated that nicotine either decreased or increased ventral hippocampal ERK1/2 activation depending on the timing of the injections. Thus, it may be that not only is a decrease in kinase activity detrimental to cognitive processes but that increases at inappropriate times may disrupt processes involved in consolidation and that the effects of acute nicotine are due to such a change. However, future studies are needed to further clarify the role of changes in cell signaling responsible for this effect. Finally, decreased levels of vHPC and dHPC pJNK1 when nicotine was administered prior to extinction, but not immediately after extinction, indicate that JNK1 activation may be specifically involved in the effects of nicotine on the formation of extinction memories.

The results of our experiments also showed that acute nicotine affected mainly vHPC ERK1/2 following both pre- and post-extinction administration of nicotine whereas JNK1 phosphorylation was affected in both dHPC and vHPC following pre-extinction injections. These differences may have resulted from intrinsic functional divergence between dHPC and vHPC. For example, Fanselow and Dong (2010) argued that while dHPC is primarily involved in cognition, vHPC is mainly responsible for emotional and stress responses through its connections to amygdala and hypothalamus. Interestingly, most effects of acute nicotine on acquisition of hippocampus-dependent learning and memory have been associated with dHPC (Kenney et al., 2010; Gould et al., 2014). Moreover, there is evidence showing that dHPC and vHPC infusions of nicotine and other nAChR modulators have opposite effects on hippocampus dependent learning (Raybuck & Gould, 2010; Kenney et al., 2012). That is, while dHPC local infusions of nicotine resulted in enhancement of contextual and trace fear conditioning, vHPC infusions resulted in deficits in these paradigms (Raybuck & Gould, 2010; Kenney et al., 2012). Moreover, acute nicotine-induced enhancement of contextual fear conditioning was associated with alterations of ERK1/2 and JNK1 in dHPC, but not in vHPC (Kenney et al., 2010; Gould et al., 2014). Therefore, it is not surprising to see a divergence between dHPC and vHPC during contextual fear extinction. In support, we recently showed that acute nicotine-induced impairment of contextual fear extinction resulted in augmented c-fos expression in vHPC but not in dHPC (Kutlu et al., 2016b). Overall, these results suggest that the effects of nicotine on contextual fear extinction may be largely mediated by vHPC.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the acute nicotine-induced impairment of contextual fear extinction may be a result of deficits in acquisition and consolidation of contextual fear extinction through alterations of the hippocampal cell signaling cascades mediating the memory consolidation process. These results may have important implications in terms of understanding the effects of nicotine addiction on fear conditioning-related psychological disorders as they suggest that nicotine alters hippocampal cell-signaling cascades in a way that it makes it harder to extinguish contextual fear memories.

Highlights.

Acute nicotine administered within the consolidation window resulted in impairment of contextual fear extinction

Acute nicotine outside the consolidation window had no effect on contextual fear extinction

Activated JNK1 and ERK1/2 protein levels in the ventral hippocampus were downregulated by pre-extinction acute nicotine administration.

Post-extinction administration of nicotine upregulated the phosphorylated form of ERK1/2 in the ventral hippocampus but had no effect on JNK1 phosphorylation.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded with grant support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (T.J.G., DA017949; 1U01DA041632), Jean Phillips Shibley Endowment, and Penn State Biobehavioral Health Department.

Footnotes

We declare no potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akirav I, Segev A, Motanis H, Maroun M. D-cycloserine into the BLA reverses the impairing effects of exposure to stress on the extinction of contextual fear, but not conditioned taste aversion. Learning & Memory. 2009;16(11):682–686. doi: 10.1101/lm.1565109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoine B, Serge L, Jocelyne C. Comparative dynamics of MAPK/ERK signalling components and immediate early genes in the hippocampus and amygdala following contextual fear conditioning and retrieval. Brain Structure and Function. 2014;219(1):415–430. doi: 10.1007/s00429-013-0505-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevilaqua LR, Rossato JI, Clarke JH, Medina JH, Izquierdo I, Cammarota M. Inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase in the CA1 region of the dorsal hippocampus blocks extinction of inhibitory avoidance memory. Behavioural pharmacology. 2007;18(5-6):483–489. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282ee7436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361(6407):31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coogan AN, O’Leary DM, O’Connor JJ. P42/44 MAP kinase inhibitor PD98059 attenuates multiple forms of synaptic plasticity in rat dentate gyrus in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;81(1):103–110. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran BP, Murray HJ, O’Connor JJ. A role for c-Jun N-terminal kinase in the inhibition of long-term potentiation by interleukin-1β and long-term depression in the rat dentate gyrus in vitro. Neuroscience. 2003;118(2):347–357. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00941-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dajas - Bailador FA, Soliakov L, Wonnacott S. Nicotine activates the extracellular signal - regulated kinase 1/2 via the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and protein kinase A, in SH - SY5Y cells and hippocampal neurones. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2002;80(3):520–530. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton GL, Wang YT, Floresco SB, Phillips AG. Disruption of AMPA receptor endocytosis impairs the extinction, but not acquisition of learned fear. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(10):2416–2426. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton GL, Wu DC, Wang YT, Floresco SB, Phillips AG. NMDA GluN2A and GluN2B receptors play separate roles in the induction of LTP and LTD in the amygdala and in the acquisition and extinction of conditioned fear. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(2):797–806. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JA, James JR, Siegel SJ, Gould TJ. Withdrawal from chronic nicotine administration impairs contextual fear conditioning in C57BL/6 mice. The Journal of neuroscience. 2005;25(38):8708–8713. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2853-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho Myskiw J, Benetti F, Izquierdo I. Behavioral tagging of extinction learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110(3):1071–1076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220875110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudai Y. The neurobiology of consolidations, or, how stable is the engram? Annual review of psychology. 2004;55:51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow MS, Dong HW. Are the dorsal and ventral hippocampus functionally distinct structures? Neuron. 2010;65(1):7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A, Radulovic M, Schrick C, Sananbenesi F, Godovac-Zimmermann J, Radulovic J. Hippocampal Mek/Erk signaling mediates extinction of contextual freezing behavior. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2007;87(1):149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricks-Gleason AN, Khalaj AJ, Marshall JF. Dopamine D1 receptor antagonism impairs extinction of cocaine-cue memories. Behavioural brain research. 2012;226(1):357–360. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould TJ, Wilkinson DS, Yildirim E, Poole RL, Leach PT, Simmons SJ. Nicotine shifts the temporal activation of hippocampal protein kinase A and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 to enhance long-term, but not short-term, hippocampus-dependent memory. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2014;109:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo A, Wellman CL, Holmes A. Brief uncontrollable stress causes dendritic retraction in infralimbic cortex and resistance to fear extinction in mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(21):5733–5738. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0474-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katche C, Cammarota M, Medina JH. Molecular signatures and mechanisms of long-lasting memory consolidation and storage. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2013;106:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney JW, Florian C, Portugal GS, Abel T, Gould TJ. Involvement of hippocampal jun-N terminal kinase pathway in the enhancement of learning and memory by nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(2):483. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney JW, Raybuck JD, Gould TJ. Nicotinic receptors in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus differentially modulate contextual fear conditioning. Hippocampus. 2012;22(8):1681–1690. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Lee S, Park K, Hong I, Song B, Son G, Kim H, et al. Amygdala depotentiation and fear extinction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(52):20955–20960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710548105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutlu MG, Gould TJ. Acute nicotine delays extinction of contextual fear in mice. Behavioural brain research. 2014;263:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutlu MG, Gould TJ. Nicotinic modulation of hippocampal cell signaling and associated effects on learning and memory. Physiology & behavior. 2016;155:162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutlu MG, Holliday E, Gould TJ. High-affinity α4β2 nicotinic receptors mediate the impairing effects of acute nicotine on contextual fear extinction. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2016a;128:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2015.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutlu MG, Tumolo JM, Holliday E, Garret B, Gould TJ. Acute nicotine enhances spontaneous recovery of contextual fear and changes c-fos early gene expression in infralimbic cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala. Learning and Memory. 2016b;23:405–414. doi: 10.1101/lm.042655.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach PT, Kenney JW, Gould TJ. Stronger learning recruits additional cell-signaling cascades: c-Jun-N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1) is necessary for expression of stronger contextual fear conditioning. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2015;118:162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach PT, Kenney JW, Gould TJ. c-Jun-N-terminal kinase 1 is necessary for nicotine-induced enhancement of contextual fear conditioning. Neuroscience letters. 2016;627:61–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XM, Li CC, Yu SS, Chen JT, Sabapathy K, Ruan DY. JNK1 contributes to metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent long-term depression and short-term synaptic plasticity in the mice area hippocampal CA1. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;25(2):391–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CH, Lee CC, Gean PW. Involvement of a calcineurin cascade in amygdala depotentiation and quenching of fear memory. Molecular pharmacology. 2003;63(1):44–52. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda S, Matsuzawa D, Nakazawa K, Sutoh C, Ohtsuka H, Ishii D, Shimizu E, et al. d-serine enhances extinction of auditory cued fear conditioning via ERK1/2 phosphorylation in mice. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2010;34(6):895–902. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miracle AD, Brace MF, Huyck KD, Singler SA, Wellman CL. Chronic stress impairs recall of extinction of conditioned fear. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2006;85(3):213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KM, Davis M. Mechanisms of fear extinction. Molecular psychiatry. 2007;12(2):120–150. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer NM, Henehan RM, Hales CA, Picciotto MR. Mice lacking the galanin gene show decreased sensitivity to nicotine conditioned place preference. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2011;98(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuutinen S, Barik J, Jones IW, Wonnacott S. Differential effects of acute and chronic nicotine on Elk-1 in rat hippocampus. Neuroreport. 2007;18(2):121–126. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328010a1ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CR, Zoladz PR, Conrad CD, Fleshner M, Diamond DM. Acute predator stress impairs the consolidation and retrieval of hippocampus-dependent memory in male and female rats. Learning & Memory. 2008;15(4):271–280. doi: 10.1101/lm.721108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, De Vries TJ. D-cycloserine administered directly to infralimbic medial prefrontal cortex enhances extinction memory in sucrose-seeking animals. Neuroscience. 2013;230:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raybuck JD, Gould TJ. The role of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the medial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in trace fear conditioning. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2010;94(3):353–363. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafe GE, LeDoux JE. Memory consolidation of auditory pavlovian fear conditioning requires protein synthesis and protein kinase A in the amygdala. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2000;20(18):RC96–RC96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-j0003.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian S, Gao J, Han L, Fu J, Li C, Li Z. Prior chronic nicotine impairs cued fear extinction but enhances contextual fear conditioning in rats. Neuroscience. 2008;153(4):935–943. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trifilieff P, Herry C, Vanhoutte P, Caboche J, Desmedt A, Riedel G, Micheau J. Foreground contextual fear memory consolidation requires two independent phases of hippocampal ERK/CREB activation. Learning & memory. 2006;13(3):349–358. doi: 10.1101/lm.80206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Hervé D, Girault JA, Caboche J. Addictive and non-addictive drugs induce distinct and specific patterns of ERK activation in mouse brain. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;19(7):1826–1836. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winder DG, Martin KC, Muzzio IA, Rohrer D, Chruscinski A, Kobilka B, Kandel ER. ERK plays a regulatory role in induction of LTP by theta frequency stimulation and its modulation by β-adrenergic receptors. Neuron. 1999;24(3):715–726. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonnacott S. Presynaptic nicotinic ACh receptors. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20(2):92–98. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Morinobu S, Fuchikami M, Kurata A, Kozuru T, Yamawaki S. Effects of single prolonged stress and D-cycloserine on contextual fear extinction and hippocampal NMDA receptor expression in a rat model of PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(9):2108–2116. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]