Abstract

Superior mesenteric artery syndrome, also known as Wilkie’s syndrome, is a rare vascular disease caused by the anomalous course of the superior mesenteric artery arising from the abdominal aorta with a smaller angle than the norm (<22°). The reduced angle compresses the structures situated between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery, such as the duodenum and left renal vein; this can determine painful crises, intestinal subocclusions, and left varicocele. This syndrome can be congenital or acquired. The acquired type is more common and is generally caused by reduced perivascular fat surrounding the abdominal aorta and the superior mesenteric artery; this form is common among anorexic patients that have had a rapid weight loss. We present the case of a female patient who suffered from repeated postprandial vomiting and who lost 12 kg in 4 months. B-mode ultrasound imaging revealed evidence of a reduced angle between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery, as found in Wilkie’s syndrome. After diagnosis, the patient followed a high-calorie diet, and 2 months later an ultrasound scan proved the restoration of the aorto–mesenteric angle as a consequence of increased perivascular fat with regression of symptoms.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Wilkie’s syndrome, Superior mesenteric artery

Sommario

La sindrome dell’arteria mesenterica superiore o sindrome di Wilkie è una patologia vascolare rara dovuta all’anomalo decorso dell’arteria mesenterica superiore che nasce dall’aorta addominale con un angolo ridotto rispetto alla norma (inferiore a 22°). L’angolazione ridotta provoca la compressione delle strutture che passano tra l’aorta e l’arteria mesenterica superiore, il duodeno e la vena renale sinistra; questo può determinare crisi dolorose, sub-occlusioni intestinali e varicocele sinistro. Questa sindrome può essere congenita o acquisita. La forma acquisita, più frequente, è dovuta in genere alla riduzione del pannicolo adiposo peri-vascolare che circonda l’aorta addominale e l’arteria mesenterica superiore; questa forma è comune soprattutto nei pazienti anoressici che hanno subito una rapida perdita di peso. Presentiamo un caso di una paziente affetta da crisi ripetute di vomito post-prandiale che ha subito una perdita di 12 kg in 4 mesi. Durante l’esame ecografico B-Mode si evidenziava una riduzione dell’angolo tra aorta ed arteria mesenterica superiore, tipico della sindrome di Wilkie. Successivamente la paziente ha eseguito una dieta ipercalorica e dopo due mesi l’ecografia dimostrava il ripristino dell’angolo aorto-mesenterico come conseguenza dell’aumento del grasso peri-vascolare con regressione dei sintomi.

Introduction

Superior mesenteric artery syndrome, also known as Wilkie’s syndrome [1–6], is a rare vascular disease with a variable incidence from 0.2% [7] to 0.78% [8], and it occurs mostly in women. It is due to the anomalous course of the superior mesenteric artery that originates from the abdominal aorta with an angle less than 22° [9]. In Wilkie’s syndrome, the reduced aorto–mesenteric angle compresses the structures that are situated between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery, such as the third portion of duodenum and the left renal vein. As a consequence, patients can have symptoms such as painful crises, postprandial vomiting [10], and/or left varicocele due to venous congestion in the left renal and spermatic or gonadic veins [11].

This syndrome can be congenital or acquired. The congenital type is less frequent and its symptoms are already present in childhood. In the acquired type, the reduction of the aorto–mesenteric angle is caused by a decrease in the perivascular fat that surrounds the abdominal aorta and the superior mesenteric artery (especially in anorexic patients). After diagnosis, the patient generally follows a high-calorie diet to increase the perivascular adipose tissue; if this therapy fails, the patient undergoes surgery to remove the duodenal compression.

The diagnosis can be made by measuring the aorto–mesenteric angle with ultrasonography.

The coexistence of an angle less than 22° and a varicocele and/or a compression of the third portion of duodenum allow us to make the diagnosis.

Case report

The 54-year-old female patient would vomit after ingesting solid and liquid food and had lost 12 kg in 4 months. She underwent a B-mode ultrasound longitudinal scan of the subxiphoidal region, in supine position, to study the abdominal aorta and superior mesenteric artery. An Aplio XG device (Toshiba) and an ultrasound convex probe (3.5 MHz) were used. The ultrasound exam was performed by an experienced operator.

The exam showed a reduction of the aorto–mesenteric angle (15°), measured at about 1 cm from the bifurcation, and a consequent decrease of the perivascular fat that surrounds the abdominal aorta and the superior mesenteric artery (diameter 2 mm) (Fig. 1a, b). Afterwards, the patient had an abdominal CT examination that confirmed both the aorto–mesenteric angle’s decrease and the compression of the third portion of the duodenum (Fig. 2), with the characteristic “beak sign” in sagittal reconstruction (Fig. 3); pelvic varicocele was also present (Fig. 4). The patient followed a high-calorie diet, and 2 months later, after the disappearance of emetic symptoms, another ultrasound scan proved a 32° aorto–mesenteric angle and an increase of the adipose tissue’s thickness (diameter 8 mm) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound examination before treatment: longitudinal subxiphoidal scan of the abdominal aorta. a The aorto–mesenteric angle is 15°. b The thickness of the perivascular fat (arrow) appears reduced. AO abdominal aorta, L liver, SMA superior mesenteric artery

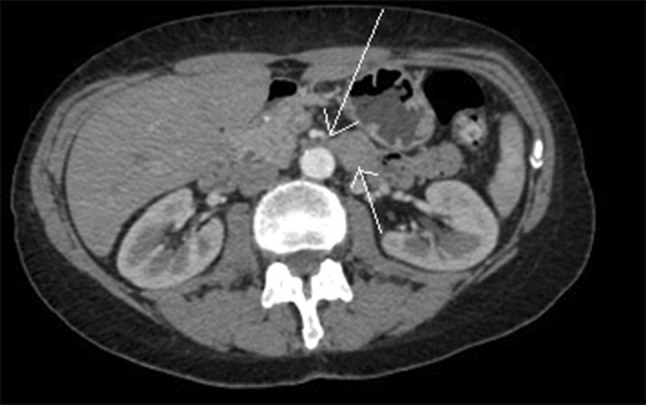

Fig. 2.

CT: the axial scanning proves the constriction of the aorto–mesenteric angle (long arrow) and the compression of the third portion of the duodenum (short arrow)

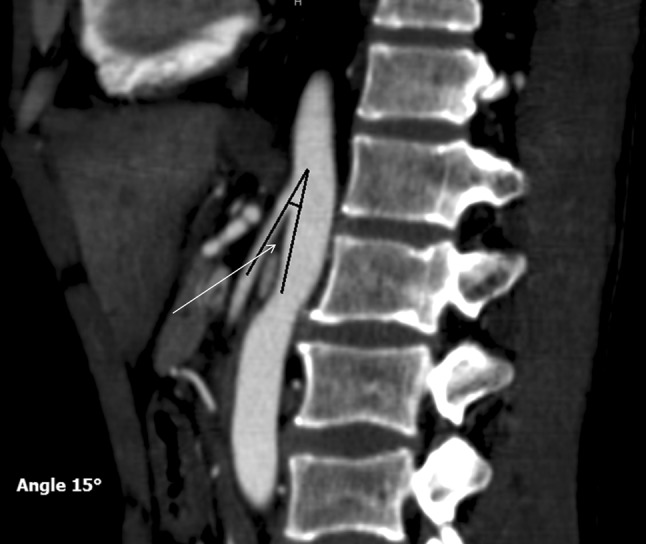

Fig. 3.

CT: the sagittal reconstruction shows the reduction of the aorto–mesenteric angle with “beak sign” (arrow)

Fig. 4.

Reconstruction CT coronal that shows left pelvic varicocele (arrows)

Fig. 5.

Ultrasound examination after the treatment: longitudinal subxiphoidal scan of the abdominal aorta. The aorto–mesenteric angle (A) is 32°. The ultrasound scan shows increased thickness of the perivascular fat (arrow). AO abdominal aorta, L liver, SMA superior mesenteric artery

Discussion

Wilkie’s syndrome is common in anorexic patients and is associated with emetic symptoms and reduced perivascular adipose tissue. Vomiting is initially self-induced, and it becomes organic as a consequence of the reduction of the aorto–mesenteric angle. The ultrasound is a very sensitive method that shows a high correlation with CT [7]: it can easily and accurately prove the decrease of the aorto–mesenteric angle, and it can also reveal the presence of varicocele (caused by the compression of the left renal vein). The CT or a contrastographic traditional examination can demonstrate the compression of the third portion of duodenum, which is responsible for the pain and emetic symptoms [12, 13]. In these patients, the first therapeutic approach is represented, as in our case, by a high-calorie diet; alternatively, they must undergo a complicated surgery to remove the duodenal compression.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals participating in the study.

References

- 1.Wilkie DPD. Chronic duodenal ileus. Am J Med Sci. 1927;173:643. doi: 10.1097/00000441-192705000-00006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwan E. Wilkie’s syndrome. Surgery. 2004;135(2):225–227. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(03)00367-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gthrie RH., Jr Wilkie’s syndrome. Ann Surg. 1971;173(2):290–293. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197102000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fong JK, Poh AC, Tan AG, et al. Imaging findings and clinical features of abdominal vascular compression syndromes. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203:29–36. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gebhart T. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2015;38:189–193. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gulleroglu K, Gulleroglu B, Baskin Baskin. Nutcracker syndrome. World J Nephrol. 2014;3:277–281. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v3.i4.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unal B, Aktas A, Kemal G, et al. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome; CT and ultrasonography findings. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2005;11(2):90–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agrawal GA, Johnson PT, Fisherman EK. Multidetector row CT of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41(1):62–65. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31802dee64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welsch T, Büchler MW, Kienle P. Recalling superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Dig Surg. 2007;24:149–156. doi: 10.1159/000102097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baltazar U, Dunn J, Floresguerra C, et al. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: an uncommon cause of intestinal obstruction. South Med J. 2000;93(6):606–608. doi: 10.1097/00007611-200093060-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inal M, Karadeniz Biligili MY, Sahin S. Nutcracker syndrome accompanying pelvic congestion syndrome; color doppler sonography and multislice CT findings: a case report. Iran J Radiol. 2014;11:11075. doi: 10.5812/iranjradiol.11075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biank V, Werlin S. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in children: a 20-year experience. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42(5):522–525. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000221888.36501.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ylinen P, Kinnunen J, Hockerstedt K. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome. A follow-up study of 16 operated patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11(4):386–391. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198908000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]