Abstract

Introduction

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic skin disease where genital involvement is relatively common. Yet health care providers do not routinely evaluate psoriasis patients for genital involvement and patients do not readily initiate discussion of it.

Methods

A qualitative study of 20 US patients with dermatologist-confirmed genital psoriasis (GenPs) and self-reported moderate-to-severe GenPs at screening was conducted to identify key GenPs symptoms and their impacts on health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Results

Patients had a mean age of 45 years, 55% were female, and patients had high rates of current/recent moderate-to-severe overall (65%) and genital (70%) psoriasis. Patients reported the following GenPs symptoms: genital itch (100%), discomfort (100%), redness (95%), stinging/burning (95%), pain (85%), and scaling (75%). Genital itching (40%) and stinging/burning (40%) were the most bothersome symptoms. Impacts on sexual health included impaired sexual experience during sexual activity (80%), worsening of symptoms after sexual activity (80%), decreased frequency of sexual activity (80%), avoidance of sexual relationships (75%), and reduced sexual desire (55%). Negative effects on sexual experience encompassed physical effects such as mechanical friction, cracking, and pain as well as psychosocial effects such as embarrassment and feeling stigmatized. Males reported a higher burden of symptoms and sexual impacts. Other HRQoL impacts were on mood/emotion (95%), physical activities (70%), daily activities (60%), and relationships with friends and family (45%). These impacts significantly affected daily activities. Physical activities were affected by symptoms and flares, and increased sweat and friction worsened symptoms. Patients reported daily practices to control outcomes.

Conclusion

The high level of reported symptoms and sexual and nonsexual impacts reflects the potential burden of moderate-to-severe GenPs. GenPs can impact many facets of HRQoL and providers should evaluate their patients for the presence of genital psoriasis and its impact on their quality of life.

Funding

Eli Lilly and Company.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13555-017-0204-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Burden of illness, Genital psoriasis, Health-related quality of life, Qualitative research

Plain Language Summary

Background

Psoriasis is a skin disease that can cause itchy, raised red patches of skin. Currently, psoriasis cannot be cured but medicines can make the patches smaller or go away completely. The patches can occur anywhere on the body. Sometimes people get them in their genital area. However, people are sensitive about this area and may not tell their doctor. Their doctor may not look or ask either.

What We Did

We interviewed 20 men and women who had moderate-to-severe genital psoriasis. We asked about their health-related quality of life, including their sex life.

What We Learned

All 20 people said they had symptoms of itching and discomfort in their genital area. Most people also had symptoms of redness, stinging or burning, pain, and scaling (flaky skin). Most people said symptoms affected their sex life. Sexual activity was less comfortable. People had sexual activity less often. Physical reasons, such as pain, bothered some people. Emotional reasons, such as being embarrassed, bothered other people more. People said the genital psoriasis affected how they felt. For example, it made them stressed, angry, or sad. Genital psoriasis made physical activities such as walking and running more uncomfortable for many people, especially when symptoms “acted up.” Sweating a lot, wearing tight underwear, or working a long day could make symptoms worse too. About half the people spent less time with their family and friends because of their symptoms. People also did things to try to reduce their symptoms. Some people wore loose clothes or soaked in a bathtub every night or after sex. Other people carried cream (to stop the itch) with them all the time.

Conclusion

Other people may not experience what these 20 people did. However, having genital psoriasis can significantly impact someone’s life. Patients and doctors should talk about it.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13555-017-0204-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease which can affect multiple body areas with different degrees of severity. Involvement of the genital area at some point in the disease course is relatively common. Many patients with psoriasis (32%–63%) reported current or past genital involvement in survey-based research [1–5], and 38% had current genital involvement confirmed by physical exam [5, 6]. The unique microenvironment of moisture, warmth, and friction can lead to fissures, erosion, and maceration, and can also reduce the appearance of scaling [7–10]. Red thin plaques and lack of scale are characteristic of genital psoriasis (GenPs) and can lead to misidentification by the patient (e.g., a sexually transmitted disease) and by health care providers (e.g., dermatitis or tinea) [9, 11, 12].

Compared to psoriasis patients without genital involvement, psoriasis patients with genital involvement report statistically significantly worse health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [3, 5] and statistically significantly greater impact on sexual health and relationships [5, 13]. Women with genital psoriasis reported statistically significantly higher sexual distress than women without it [3]. Psoriasis patients with involvement of “sensitive” regions (the lower abdomen and genitals) report greater feelings of stigmatization compared to patients with visible hand, scalp, neck, and facial lesions [14]. However, despite this impact of genital symptoms, patients frequently do not broach the subject with their health care providers [4, 13]. Similarly, providers neither commonly question nor examine patients for its presence [3, 15]. More detailed descriptions from patients on the impact of GenPs may help encourage providers to identify and ultimately appropriately treat patients with GenPs. A qualitative study was undertaken of patients with GenPs to identify key GenPs symptoms and their impact on HRQoL from the patients’ perspectives.

Methods

Study Design

This was a cross-sectional, qualitative study of 20 male and female patients with GenPs. A targeted literature review and input from two US-based clinicians specializing in dermatology and research into general psoriasis and GenPs (authors CR and SF) led to the development of the draft conceptual model which underlies the semi-structured interview guide. The model (Fig. S1 in the Electronic supplementary material, ESM) asserts that (1) GenPs symptoms influence short-term functional outcomes and (2) these short-term functional outcomes have distal impacts, including sexual and social endpoints.

The interview comprised two components: concept elicitation and cognitive interviews. During concept elicitation, patients were asked an open-ended question about the GenPs symptoms they experienced (without any definition of symptoms) and were then probed for more detail on the symptoms they reported as well as on predefined symptoms of itching, pain, scaling, discomfort, redness, and stinging/burning, whether spontaneously reported or not. The same pattern was followed for sexual health and HRQoL: open-ended questions followed by specific topic probes. Predefined sexual health topics were sexual desire, sexual experience, sexual frequency, worsening of symptoms after sexual activity, and avoidance of sexual relationships. Predefined HRQoL topics were physical activities, mood or emotional status, social or leisure activities, work/school, daily activities, and relationships with family/friends. Responses were both spontaneous and probed. During the cognitive interviews, patients completed two draft patient-report outcomes (PRO) measures, the Sexual Function Questionnaire and Genital Psoriasis Symptom Severity, and were asked for their feedback on the measures. Data from these two PROs will be covered in separate manuscripts. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, good clinical practice, and all applicable laws and regulations. Although informed consent and institutional review board (IRB) oversight were waived by the local IRB (Chesapeake IRB, Columbia, MD), all participants gave written and verbal informed consent prior to commencing the interview.

Patient Recruitment

Patients were recruited in the continental USA by clinical staff from five clinical sites located in four states (Arkansas, Indiana, Michigan, and Washington). Clinical staff identified potential participants through review of clinical charts and screened them for study eligibility either in person or over the telephone. All patients had current or past GenPs confirmed by a dermatologist. At the time of screening, eligible adults (≥ 18 years) required a physician diagnosis of chronic plaque psoriasis (≥ 6 months duration); current or recent history (within 3 months) of moderate or severe genital involvement (per Patient Global Assessment ≥ 4, 6-point scale from 0 to 5); confirmation by a dermatologist of overall psoriasis, affected body surface area ≥ 1%, and plaque psoriasis in extragenital areas; and intolerance of or failure to respond to ≥ 1 topical therapy, which included over-the-counter topicals, for GenPs.

Data Collection

A sample of up to 25 male and female patient interviews was proposed. One-on-one interviews were conducted and patients could choose to be interviewed in-person or on the telephone. Interviews were conducted between August 19, 2015 and November 19, 2015 by trained Evidera research associates (2 females [PhD, BS], 1 male [MS, RPh]), including JLP, PhD (author). Patients were asked if they preferred a gender-matched interviewer or had no preference, and a preference, when expressed, was matched when possible. All interviewers had at least 18 months’ experience in the conduct of qualitative interviews and had received specific training for this study protocol. Prior to telephonic interviews, packets containing the informed consent form were mailed to subjects. Interviewers’ reasons and interests in the research topic were described in the informed consent forms. Patients completed a brief sociodemographic questionnaire during the interview.

Each patient’s interview was completed in one session lasting approximately 2 h. When finished, patients were remunerated for their time (estimated as fair market value). Upon completion of an interview, clinic site staff completed a clinical questionnaire on the medical history for each patient which included date of diagnosis with overall psoriasis and GenPs, affected body surface area, severity of GenPs, current GenPs status, and current GenPs medications. During the interview, GenPs was defined for women as symptoms of psoriasis that occur “on the outer lip, the inner lip, and the area between your vagina and the anus” and for men as “the area of the penis, the scrotum, and the area between the penis and the anus.”

Data Analysis

The data for this paper focus largely on the concept elicitation interview component; the exception is that sex life satisfaction data derives from the Sexual Function Questionnaire administered during the cognitive interview component. All patient interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed by a third-party professional transcriber, and reviewed by the study team for quality assurance purposes. Personal health information was redacted and obvious transcription errors were corrected.

A content analysis approach was used to analyze the qualitative data (based on notes, transcripts, and audio recordings) from the interviews [16]. This approach uses empirical data to validate that measurement tools and their underlying conceptual framework are consistent with the experiences and perspectives of patients. Based on the semi-structured interview guide and further refined by additional specific details that emerged from the interviews, a coding dictionary was developed by a member of the research team (JLP). One research associate coded the transcripts and all coding was reviewed by JLP. A qualitative analysis software program, ATLAS.ti (version 7.5.9, Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany), was used by the study team to systematically identify and code themes within the transcripts which were then organized in chronological order by date of interview and tabulated to document and quantify the emergence of concepts related to the study objectives. Data were organized chronologically in order to determine the point at which saturation of concepts was reached. Saturation, the point at which gathering additional data does not yield additional new concepts, was reached with the 20 interviews. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, frequency) were used to characterize the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the population.

Results

Patients

Of the 25 screened patients, 22 met the inclusion criteria. Two eligible subjects were unavailable for participation, and 20 patient interviews and clinical assessments were completed. All patients chose telephonic interviews and declined face-to-face meetings.

The mean age was 45 years (range 21–68), 55% (n = 11) were female, and 90% (n = 18) were white (Table 1). The mean durations since diagnosis for overall psoriasis and GenPs were 18 and 7.5 years, respectively, but seven patients (35%) were diagnosed with overall psoriasis and GenPs during the same year, and the relative timing of their two diagnoses is unknown. At the time of their interview, in the 3 months prior, most patients (n = 13, 65%) reported current/recent moderate-to-severe overall psoriasis (n = 8, 40% rated it severe), and the majority (n = 14, 70%) reported current/recent moderate-to-severe GenPs (n = 6, 30% rated it severe). (Note that all patients met the study criteria at screening per the requirements of the protocol.) Current extragenital psoriasis was most common on the scalp (n = 17, 85%), and hands, feet, and/or nails (n = 13, 65%) (Table 1). Seventy percent of patients were currently receiving at least one GenPs treatment which included biologics (n = 11, 55%) and topicals (n = 7, 35%).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | N | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 20 | 45 (14.2) |

| Gender (female), n (%) | 20 | 11 (55) |

| Race (white), n (%) | 20 | 18 (90) |

| Duration of psoriasis diagnosis (years), mean (SD)a | 19 | 18 (14) |

| Duration of genital psoriasis diagnosis (years), mean (SD)a | 20 | 7.5 (9.7) |

| Body surface area, mean (SD)a | 15 | 10.4 (12.7) |

| Currently receiving treatment for genital psoriasis,a,b,c n (%) | 20 | 14 (70) |

| Biologics including investigational products | – | 11 (55) |

| Topicals (including OTC) | – | 7 (35) |

| Phototherapy | – | 0 |

| Self-reported genital psoriasis symptom severity at its worst over the past 3 months, n (%) | 20 | |

| 0–1 (0 = clear) | – | 0 |

| 2–3 | – | 6 (30) |

| 4–5 (5 = severe) | – | 14 (70)d |

| Self-reported overall psoriasis symptom severity at its worst over the past 3 months, n (%) | 20 | |

| 0–1 (0 = clear) | – | 1 (5) |

| 2–3 | – | 6 (30) |

| 4–5 (5 = severe) | – | 13 (65) |

| Self-reported current localization of psoriasis other than genital psoriasis,c n (%) | 20 | |

| Scalp | – | 17 (85) |

| Hands, feet, and/or nails | – | 13 (65) |

| Face | – | 11 (55) |

| Skin folds (i.e., armpits, under the breasts) | – | 10 (50) |

| Other (responses included: limbs, buttocks, trunk, knees, elbow, ears) | – | 14 (65) |

| Sexual activity status, n (%) | 20 | |

| Active | – | 9 (45) |

| Not active | – | 9 (45) |

| Not askede | – | 2 (10) |

OTC over the counter, SD standard deviation

aPatient clinical characteristics as reported by clinicians

b N = 13 patients self-reported that they were currently receiving treatment for psoriasis. From the clinical forms, current treatment was documented by clinic site staff for N = 14 patients

cResponses not mutually exclusive

dAll patients met study criteria at screening of self-reported genital psoriasis (Patient Global Assessment ≥ 4, 6-point scale); these data report status at the time of the interview

ePer interviewers’ judgment, the question was not asked due to auditory cues, conversation flow, and patient’s apparent lack of comfort with sensitive topics

Patient-Reported Genital Psoriasis Symptoms

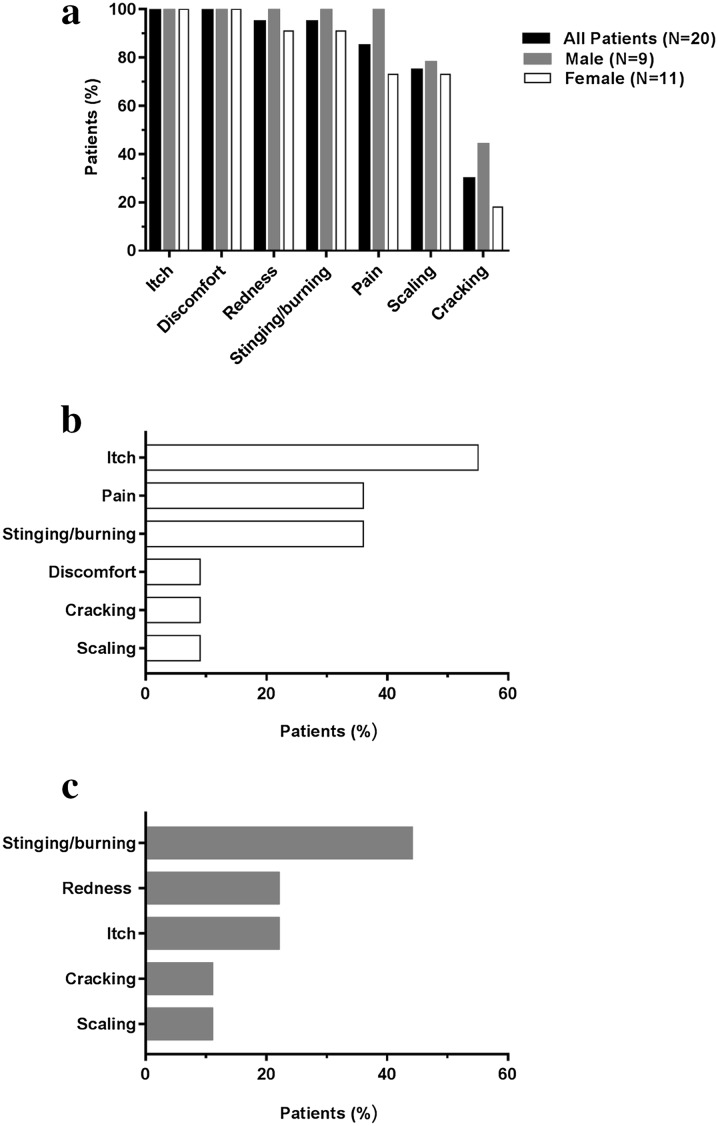

Patients reported multiple genital symptoms. The most commonly reported were itch and discomfort (both n = 20, 100%), redness (n = 19, 95%), stinging/burning (n = 19, 95%), pain (n = 17, 85%), and scaling (n = 17, 75%) (Fig. 1a). Thirty percent (n = 6) of patients reported cracking. Patients also reported flaking (n = 4, 20%), dry skin (n = 3, 15%), pimples (n = 2, 10%), being more susceptible to illness (n = 2, 10%), bleeding, inflammation, irritation, mental discomfort, oozing, bad odor, and swelling (each n = 1, 5%). Of these, the “most bothersome” symptoms (patients could report ≥ 1 symptom) were itch and stinging/burning (both n = 8, 40%).

Fig. 1.

Frequency of patient reported genital psoriasis symptoms. Patients with current or recent (≤ 3 months) moderate-to-severe GenPs were asked an open-ended question (without any definition of symptoms) about the GenPs symptoms they experienced and were also questioned on predefined symptoms, whether spontaneously reported or not. Patients were asked which symptom(s) were the most bothersome (patients could report more than one symptom). a Frequency of symptoms. b Most bothersome symptom(s) for females (N = 11). c Most bothersome symptom(s) for males (N = 9)

Qualitatively, gender differences were observed. All females (n = 11, 100%) reported experiencing itch and discomfort, whereas all males (n = 9, 100%) reported itch, discomfort, redness, stinging/burning, and pain (Fig. 1a). Half of females reported itch as the most bothersome symptom (n = 6, 55%) (Fig. 1b) whereas males reported stinging/burning as the most bothersome symptom (n = 4, 44%) (Fig. 1c).

Differences Between Genital and Nongenital Psoriasis Symptoms

Most patients (n = 18, 90%) reported that some aspect of GenPs was more intense and/or unique compared to extragenital psoriasis (see Table 2 for representative patient quotations). Several features were identified. First was the constant intensity of, awareness of, and/or need to manage a symptom in GenPs versus in other locations. Itching was commonly reported for its intensity, and in some cases patients scratched until bleeding occurred. Second was the sensation of pain, particularly that linked to itching. The pain sensation could have the effect of limiting sexual activity and social life (below). Finally, two patients reported feeling self-conscious that their GenPs might be misidentified as a sexually transmitted disease. Patients attributed the differences with GenPs as due to thinner, more tender skin, more moistness and sweat, greater impact from sweat, increased friction from skin or clothes, and topical treatments not lasting as long.

Table 2.

Patient-reported differences between genital and nongenital psoriasis

| Representative patient quotations |

|---|

| Itch |

| [On my arms and legs] it’s just itching, and I scratch it until the itch goes away. But the only place I’ve ever bled was in my genitals because I scratch so much. (F) |

| It’s totally different. It’s like the itch you can’t ever get rid of it. (F) |

| [My other psoriasis] itches, it may be 5 or 7 intermittently, but there’s almost never pain, burning. [Genital psoriasis] itches 24 h a day, a subliminal pain or itch. You can’t scratch it 24 h a day. Then because you’re not scratching it, the itch becomes a discomfort, a distraction. (M) |

| Pain |

| Other places on my body might itch more, but genital psoriasis is definitely one that hurts the most. (M) |

| The psoriasis I have on my elbows and my knees, there…may be a little discomfort associated. But it’s certainly nothing that affects how I live my life. Whereas the psoriasis has resulted in behavioral changes on the genital side. The pain would be really only in the genital area. (F) |

| This is a different pain. With my psoriasis on the other parts of my body, it’s like some mornings I can’t even get out of bed it hurts so bad. (F) |

| Discomfort |

| When you walk, sit, stand, you are always using that area. I can’t not notice the discomfort. (F) |

| I don’t really have pain with it. But you can’t dry [that area] out so it stays wet and sore all the time. (F) |

| Stinging/burning |

| The itching is worse on my scalp where I have the thick erythema. The burning is worse in the genital area, it’s like putting a hot match head on your skin. (M) |

| Cracking |

| The other parts of my body all hurt. But they doesn’t ever crack and bleed like my penis and scrotum area…When it cracks it’s exposed to this newer skin so it’s very, very sensitive. Showers are always painful for the first or second day. (M) |

| Mistaken for STD |

| I become more self-conscious…a sexual partner or someone else may possibly perceive that as a sexually transmitted disease. (M) |

F female, M male, STD sexually transmitted disease

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 patients with genital psoriasis. Selected quotations are from patients and have been edited to minimize repetitive language

Effect of Genital Psoriasis on Sexual Activity

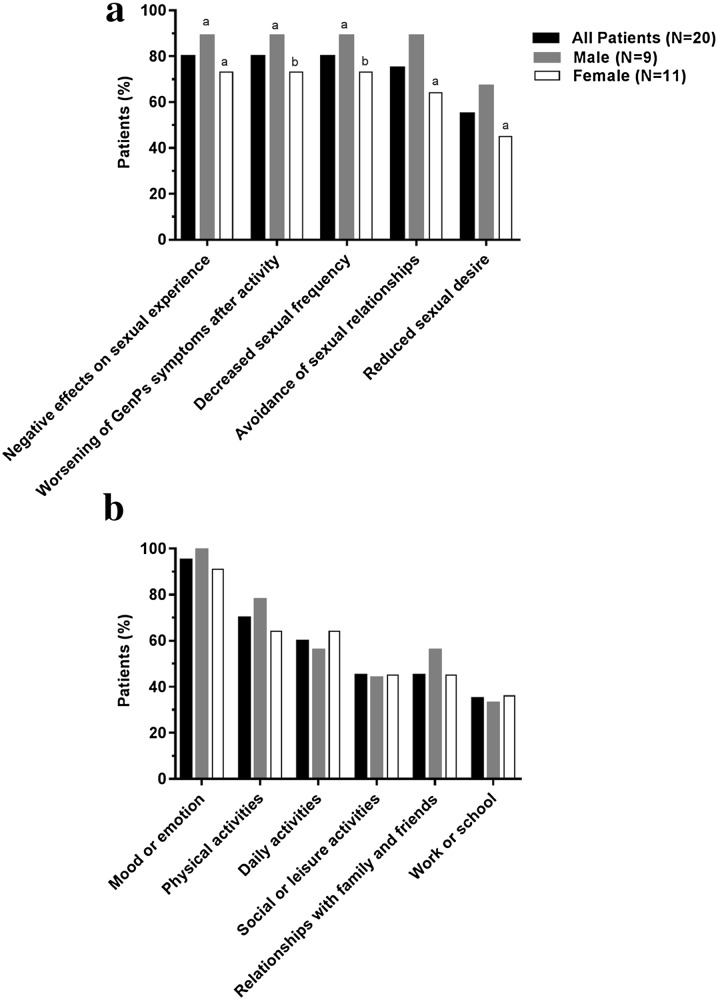

A higher percentage of men reported being “currently sexually active” than women (67% versus 27%). GenPs affected many aspects of sexual health. Nearly all patients (n = 18, 90%) reported at least one negative impact on sexual activity. These included impaired sexual experience during sexual activity (n = 16, 80%) (defined broadly to include intercourse and activities such as masturbation), worsening of symptoms after sexual activity (n = 16, 80%), decreased sexual frequency (n = 16, 80%), avoidance of sexual relationships (n = 15, 75%, which men reported more frequently than women, 89% vs 64%), and reduced sexual desire (n = 11, 55%) (Fig. 2a). In the week prior to the interview, half of patients reported that GenPs affected their sex life satisfaction “quite a bit” or “very much” (each n = 5, 25%), 30% (n = 6) responded “not at all,” 10% (n = 2) reported “somewhat,” 5% (n = 1) reported “a little bit”,” and 1 patient (5%) had not had GenPs symptoms in the past week. Nearly half (45%) of patients reported sexual inactivity (Table 1), but they were not asked if the current inactivity was related to GenPs or another reason.

Fig. 2.

Frequency of patient-reported impacts from genital psoriasis. Patients with current or recent (≤ 3 months) moderate-to-severe GenPs were asked an open-ended question about the impact GenPs had on their lives and were also questioned on prespecified impacts, whether spontaneously reported or not. a Frequency of sexual impacts. b Frequency of nonsexual impacts. aPer interviewers’ judgment, the question was not asked of one patient due to auditory cues, conversation flow, and the patient’s apparent lack of comfort with sensitive topics. bPer interviewers’ judgment, the question was not asked of two patients due to auditory cues, conversation flow, and the patients’ apparent lack of comfort with sensitive topics

Negative effects on sexual experience encompassed physical effects such as mechanical friction, cracking, and pain and psychosocial effects such as embarrassment and feeling stigmatized. The physical effects could linger for hours, if not days, as prolonged pain and discomfort. This led some patients to intervene with immediate self-made treatments (such as bathing in Epsom salts) to control post-activity symptoms. Some patients described proactively weighing the value of a potential intimate encounter against its potential subsequent pain and discomfort. Not surprisingly, decreases in frequency and avoidance of sexual relationship were common. Patients not in relationships described embarrassment or a reluctance to reveal their GenPs to someone, and those in long-term relationships, even with understanding partners, described the emotional toll their avoidance incurred on the relationship (quotations in Table 3).

Table 3.

Patient-reported impacts of genital psoriasis on sexual activity

| Representative patient quotations |

|---|

| Negative effects on sexual experience |

| Foreplay, that is almost unheard of because of the friction and the irritation. (F) |

| The stinging during sex, it is just a terrible feeling. (M) |

| When psoriasis cracks, it’s like a paper cut. And if I get a full erection, I’d get three or four of those, laterally, along the side of the penis. The pain was unbelievable. (M) |

| Definitely the embarrassment… I’ve had one boyfriend make a comment, is that, what’s this? (F) |

| Even during the course of a long-term relationship, I still can’t get it out of my mind how I feel slightly more judged by it, even if I’m not being so. (M) |

| Worsening of symptoms after activity |

| It just makes the itch worse. (F) |

| During [intercourse] hurts because of getting an erection and elongating the penis…then afterwards is when you notice the majority of the pain…from the friction and the rubbing and this newer exposed red skin that is very sore and tender. (M) |

| [Deciding to have sex] is a calculated decision as to what the cost is going to be and pain and discomfort post-activity for hours and/or days. (M) |

| If his stuff gets on there, it sets it on fire…you just have to immediately sit in another Epsom salt bath…it’s just like three days…of hell, so it’s not worth it to me. (F) |

| Decreased sexual frequency |

| Post-[genital] psoriasis, I’m not nearly as active as I was. (M) |

| Avoidance of sexual relationship |

| I told him…if it comes between having sex—because it’s so painful—and…not being married, then I choose not to be married. (F) |

| There’s no sex life. First of all, you don’t want to expose yourself. But I’m single and I don’t want to think about dating because I’m not ready to share with a stranger. (F) |

| I pursue my own pleasure a lot less…I’m really not interested in pleasure if it’s associated with pain. So, I rarely initiate intimacy which is devastating [and] hurts my husband’s feelings. (F) |

| To be honest with you, I kind of stay withdrawn from too much contact with the wife, I don’t want it to lead to anything. (M) |

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 patients with genital psoriasis. Selected quotations are from patients and have been edited to minimize repetitive language

F female, M male

Effect of Genital Psoriasis on Nonsexual Aspects of HRQoL

GenPs led to impairment of HRQoL beyond sexual health, including on mood/emotion (n = 19, 95%), physical activities (n = 14, 70%), daily activities (n = 12, 60%), social or leisure activities (n = 9, 45%), relationships with friends and family (n = 9, 45%), and work or school (n = 7, 35%) (Fig. 2b). Patients reported feeling stressed, frustrated, angry, anxious, depressed, sad, and embarrassed due to GenPs, which could trigger distraction, self-consciousness, lowered self-esteem or confidence, feeling less desirable, helplessness hopelessness, concern for the future, and wondering “why me?”

The physical component was affected by symptoms and flares which inhibited physical activities (such as walking, running, or swimming in chlorinated pools), and by increased friction and sweat (e.g., a longer work day, increased sweating from exertion or weather conditions, or not being able to treat symptoms promptly). Even sitting was reported to be uncomfortable by some patients. Other factors which worsened GenPs included stress, dryness in winter, lack of sleep, and drinking alcohol. The impairments led patients to eliminate certain physical activities, reduce intensity, or limit the number of activities in a day (quotations in Table 4).

Table 4.

Patient-reported impact of genital psoriasis on nonsexual HRQoL

| Representative patient quotations |

|---|

| Mood/emotion |

| The pain brings on discomfort and then it just triggers everything else, the stress and the anxiety and emotions and everything… It all just works together against me. (F) |

| The redness is not really terribly uncomfortable anymore if I take care of it, but it’s always there. And that’s kind of a mental thing. (M) |

| It’s affected my life in so many ways. What I can wear, what activities I can involve myself in…I don’t really like to do a whole lot because I am feeling discomfort with the stress, and lack of confidence whether it be with my partner or…just everyday life. (F) |

| Physical activity |

| If it’s flaring up and the skin is very raw, I can’t [go for a run] because of the friction. I don’t swim anymore, not in chlorine. (M) |

| It gets worse if I’m working in the yard or playing with my dogs or… moving around more, it naturally becomes more irritated… Walking, sitting, you can’t sit comfortably. Walking, that’s the worst painfulness. (F) |

| I try to keep cream and powder down there so I won’t itch when I’m working around people… [But] if I’ve been outside working out in the heat or if I’ve been doing a lot of sweating, it’s really bad. (F) |

| It does not bother me much but if I work a 10- or 12-hour shift, it begins to itch and then I cannot wait to get home to shower and clean things and put more medication on. (M) |

| Daily activities |

| You’re laying [sic] in bed at night and you can’t get comfortable because no matter how you turn, that signal, that sensory signal goes there. (M) |

| Especially when I go to the bathroom. Urine burns. It really burns it. (F) |

| I am uncircumcised…and it’s difficult and even painful to pull the foreskin back to urinate or for sexual activities as well. (M) |

| [When it cracks] I wrap [my penis] in toilet paper to keep it from burning or stinging or touching my boxers or anything. (M) |

| Sometimes when you sit in a chair, it’s not comfortable or you always feel like you want to pull your panties away from your body. (F) |

| The skin is very, very thin and any friction or irritation, even underwear, is uncomfortable. (M) |

| You always have to be prepared and carry around panty liners…when it’s bad, if I have on a pair of shorts and I sit down on a cushion, you know, things might leak through [due to oozing]. That’s what I call high maintenance. (F) |

| Dr. X has given me creams and stuff…but they wash off when I go to the bathroom. I always wear a pad just in case it starts to bleed. (F) |

| And if you’re sweating or you’re active or your shorts bunch up, it becomes very uncomfortable. But it’s chronic…you may not notice it for an hour, but you don’t go 6 hours without it being noticeable. (M) |

| 10 out of 10 is when…everything is so bad that I actually get nauseous from it, have to run to the bathroom and wash the area. (F) |

| Personal relationships |

| I was embarrassed and thought there was something wrong with me…I had all these concerns…that no one will ever want me. I won’t be able to have a girlfriend or wife. (M) |

| I’m not social any more. I’ve become a recluse…if it starts itching or something…it’s not seemly that you would be able to take care of yourself in a public situation. (F) |

| It’s not like I ever want to be naked around anyone when that’s going on. So from showering in a locker room to in a relationship, it puts you on a more guarded and different level. (M) |

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 patients with genital psoriasis. Selected quotations are from patients and have been edited to minimize repetitive language

F female, M male

These impacts significantly affected daily activities, such as painful urination and poor sleep hygiene due to difficultly in falling asleep and unconscious scratching while sleeping. Patients reported many common practices in their daily life to control symptoms. These included, for example, choosing loose-fitting clothes based on comfort, daily routines of a shower or soaking bath, needing to carry certain supplies (e.g., ointments and creams to treat symptoms, panty liners because of oozing), or taking specific precautions (e.g., a male patient wrapped his penis in tissue paper during periods of post-cracking hypersensitivity). These HRQoL impairments led to decreased interactions with family and friends and social networks as some patients reported that their symptoms lead them to be nonsocial (e.g., fear of itching badly and not being able to scratch in social situations, fear of nakedness in front of others, etc.) (quotations in Table 4).

Patients also described learning to cope with their GenPs, which included finding treatment regimens and routines that reduced symptoms and improved their quality of life.

General Themes

General themes emerged. A first theme was the constant intensity and/or awareness of some aspects of GenPs, such as itching, friction, or symptoms that repeated themselves in a continuous cycle. A second theme was that GenPs presented some different challenges than extragenital psoriasis (i.e., intensified sensation of pain or discomfort and being associated with the stigma of sexually transmitted diseases). A third was the toll of GenPs on sexual life and relationships, whether in actual or potential situations. The final theme was the mental and emotional strain of GenPs. Patients spoke of being distracted during social interactions, isolating themselves, needing to be always vigilant in their efforts to control symptoms, and learning to ignore their symptoms and “turn it off” and “not let it get me down.”

Discussion

This qualitative study of patients with moderate-to-severe GenPs showed that GenPs led to multiple specific psychosexual and psychosocial impairments. Symptoms were reported to be more intense and/or constant in GenPs than in extragenital psoriasis, and nearly all patients reported negative impacts on both sexual and nonsexual quality of life. The disproportionate impact of GenPs has been recognized by some treatment and consensus guidelines. Due to the physical, emotional, and social burden of GenPs on patients, guidelines for the treatment of psoriasis suggest that even in patients with low body surface area involvement, involvement of genital skin may justify its classification as moderate or severe disease and thus warrant systemic treatment, especially if topical treatments are ineffective [17, 18].

The level of reported symptoms in this study was high. The majority of our patients reported current/recent moderate-to-severe GenPs, and the high level of reported GenPs symptoms likely reflects this disease burden. In terms of reported symptoms, all patients reported itch, which is common to GenPs patients [12] as well as to patients with extragenital psoriasis (77%–88%) [19–21]. Itch was also reported as one of the most bothersome symptoms, consistent with the study by Meeuwis and colleagues [4] in which GenPs patients reported itch and redness had the “highest intensity.”

The impact of GenPs described by patients in this study was pronounced. Patients with plaque psoriasis in extragenital locations already report impairment of sexual health [22–25], but the presence of GenPs incurs an additional toll [3, 5]. This current study sheds light on the impact of high GenPs disease burden on multiple aspects of sexual experience and relationships. The reported high level of nonsexual impacts, particularly on mood/emotions, physical activities, and daily activities, is supported by the findings of more severe impairment on HRQoL [3, 5] and greater depression [5, 13] in psoriasis patients with versus without genital involvement. Psoriasis patients with pain experience interference with function significantly more frequently and more severely compared to patients with skin discomfort [26]. The high rates of reported pain and discomfort in this study underscore their impact on emotions and daily life.

Interesting differences were observed between men and women in this study. Men not only reported a higher symptom frequency burden than women, but 8 of the 9 men also reported significant sexual impacts. The most bothersome symptoms differed, with itch being most bothersome for women and stinging/burning most bothersome for men. These findings may reflect the higher prevalence in this study of cracking in men or biological and/or psychological differences between the genders [4]. Despite their higher burden, men reported a higher level of sexual activity and greater avoidance of sexual relationships than women, which could suggest that more men maintained sexual activity through masturbation.

One important finding was the time lag between mean diagnosis of general psoriasis and GenPs, with the diagnosis of extragenital psoriasis predating that of GenPs for many patients. Given that estimates of the proportion of psoriatic patients with a current or past history of GenPs range from 32% to 63% [1–5], patients with psoriasis are at risk for developing GenPs. The disease currently engenders reluctance amongst patients and even some health care providers to discuss it or physically examine the genital area, yet it can significantly impact many facets of patient quality of life. Providers should consider genital involvement as a possibility in patients with psoriasis and provide appropriate follow-up.

The extent to which these findings can be generalized to all GenPs patients may be limited. The overall sample size (N = 20) and gender subgroups (11 females and 9 males) were small and geographically limited to four states in the continental US. Racial minorities were underrepresented. Sexual identity was not elicited during the interview and the perspectives of patients in same-sex relationships or transgender patients were not explicitly represented. Recruitment occurred in clinics and patients not seeking allopathic care were underrepresented. Patients with greater impairments may be more inclined to share their experience, leading to selection bias, and other biases during the interviews or data interpretation could have come into play. The finding that all patients preferred telephone, rather than face-to-face, interviews leads the authors to speculate that the social distance afforded by the telephone may reflect patients’ embarrassment or discomfort.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this qualitative study of patients with high rates of moderate-to-severe GenPs reported multiple psychosexual and psychosocial impairments from their GenPs symptoms. The details of patients’ “lived experience” in illuminating the burden and impact of GenPs attests to a role for qualitative research in psoriasis research [19, 27]. Given the chronic nature of psoriasis, providers may want to consider that patients with psoriasis may have or could develop genital involvement. Future studies should look at treatments which help patients with GenPs maintain or achieve a higher level of quality of life and sexual functioning. Additionally, studies are needed to examine the factors involved in the reluctance of health care providers and patients to discuss GenPs and its impact on HRQoL. Lastly, patients’ subjective quality of life is an important factor in determining appropriate treatment and should be considered in addition to the total body surface area of involvement.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA, which contracted with Evidera, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, for the design and analysis of the study. Article processing charges were funded by Eli Lilly and Company. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and give final approval for it to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. The authors sincerely thank all the patients who participated in the research. Medical writing support was provided by Cate Jones, PhD, of Eli Lilly and Company, who fulfilled the ICMJE criteria for authorship and is a listed author.

Disclosures

Jennifer Clay Cather has served as investigator for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, and Sun Pharma involving drugs for the treatment of psoriasis, and is on the speaker’s board or advisory board for AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, and Sun Pharma. Caitriona Ryan has acted as an advisor and/or speaker for AbbVie, Aqua, Dr Reddy’s, Eli Lilly and Company, Medimetriks, Novartis, Regeneron-Sanofi, UCB, and Xenoport. Kim Meeuwis has provided consultancy services, has been a speaker, or received honoraria from Eli Lilly and Company and Eucerin, and is on the medical advisory board of Eucerin. Alison J. Potts Bleakman is an employee of Eli Lilly and Company and owns stock. April N. Naegeli is an employee of Eli Lilly and Company and owns stock. Emily Edson-Heredia is an employee of Eli Lilly and Company and owns stock. Cate Jones is an employee of Eli Lilly and Company and owns stock. Jiat Ling Poon is an employee of Evidera, with which Eli Lilly and Company contracted to design and conduct the study. Ashley N. Wallace has no conflicts of interest to declare. Lyn Guenther has received psoriasis research funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer lngelheim, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Merck Frosst, Pfizer, and UCB, and has been a consultant and speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Merck Frosst, Pfizer, Tribute, UCB, and Valeant. Scott Fretzin has served as a speaker for Eli Lilly and Company. Caitriona Ryan was consulted by Evidera to better understand patients’ experience of genital psoriasis. Scott Fretzin was consulted by Evidera to better understand patients’ experience of genital psoriasis.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, good clinical practice, and all applicable laws and regulations. Although informed consent and institutional review board (IRB) oversight were waived by the local IRB (Chesapeake IRB, Columbia, MD), subjects gave written informed consent and verbal consent prior to audio recording.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are in the form of audio recordings and transcripts, and are not publicly available due to patient privacy.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/62CCF0604618A478.

References

- 1.Fouéré S, Adjadj L, Pawin H. How patients experience psoriasis: results from a European survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(Suppl 3):2–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meeuwis KA, de Hullu JA, de Jager ME, Massuger LF, van de Kerkhof PC, van Rossum MM. Genital psoriasis: a questionnaire-based survey on a concealed skin disease in the Netherlands. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1425–1430. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meeuwis KA, de Hullu JA, van de Nieuwenhof HP, et al. Quality of life and sexual health in patients with genital psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1247–1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meeuwis KA, van de Kerkhof PC, Massuger LF, de Hullu JA, van Rossum MM. Patients’ experience of psoriasis in the genital area. Dermatology. 2012;224:271–276. doi: 10.1159/000338858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan C, Sadlier M, De Vol E, et al. Genital psoriasis is associated with significant impairment in quality of life and sexual functioning. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:978–983. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ji S, Zang Z, Ma H, et al. Erectile dysfunction in patients with plaque psoriasis: the relation of depression and cardiovascular factors. Int J Impot Res. 2016;28:96–100. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2016.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buechner SA. Common skin disorders of the penis. BJU Int. 2002;90:498–506. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2002.02962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guglielmetti A, Conlledo R, Bedoya J, Ianiszewski F, Correa J. Inverse psoriasis involving genital skin folds: successful therapy with dapsone. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2012;2:15. doi: 10.1007/s13555-012-0015-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meeuwis KA, de Hullu JA, Massuger LF, van de Kerkhof PC, van Rossum MM. Genital psoriasis: a systematic literature review on this hidden skin disease. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:5–116. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weichert GE. An approach to the treatment of anogenital pruritus. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:129–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreassi L, Bilenchi R. Non-infectious inflammatory genital lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czuczwar P, Stępniak A, Goren A, et al. Genital psoriasis: a hidden multidisciplinary problem—a review of literature. Ginekol Pol. 2016;87:717–721. doi: 10.5603/GP.2016.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zamirska A, Reich A, Berny-Moreno J, Salomon J, Szepietowski JC. Vulvar pruritus and burning sensation in women with psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:132–135. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmid-Ott G, Kuensebeck HW, Jaeger B, et al. Validity study for the stigmatization experience in atopic dermatitis and psoriatic patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:443–447. doi: 10.1080/000155599750009870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, Feldman SR, Gelfand JM, American Academy of Dermatology Work Group et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 6. Guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: case-based presentations and evidence-based conclusions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:137–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leidy NK, Vernon M. Perspectives on patient-reported outcomes: content validity and qualitative research in a changing clinical trial environment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26:363–370. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menter A, Gottlieb A, American Academy of Dermatology Work Group et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriatic with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826–850. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mrowietz U, Kragballe K, Reich K, et al. Definition of treatment goals for moderate to severe psoriasis: a European consensus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011;303(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00403-010-1080-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pariser D, Schenkel B, Carter C, et al. A multicenter, non-interventional study to evaluate patient-reported experiences of living with psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 2016;27:19–26. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2015.1044492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prignano F, Ricceri F, Pescitelli L, Lotti T. Itch in psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical aspects and treatment options. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2009;19(2):9–13. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S4465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yosipovitch G, Goon A, Wee J, Chan YH, Goh CL. The prevalence and clinical characteristics of pruritus among patients with extensive psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(5):969–973. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Schupp CW. Psoriasis and sexual behavior in men: examination of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in the United States. J Sex Med. 2014;11:394–400. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Psoriasis and sex: a study of moderately to severely affected patients. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:259–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sampogna F, Gisondi P, Tabolli S, Abeni D. IDI multipurpose psoriasis research on vital experiences investigators. Impairment of sexual life in patients with psoriasis. Dermatology. 2007;214:144–150. doi: 10.1159/000098574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Türel Ermertcan A, Temeltas G, Deveci A, Dinç G, Güler HB, Oztürkcan S. Sexual dysfunction in patients with psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2006;33:772–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ljosaa TM, Rustoen T, Mörk C, et al. Skin pain and discomfort in psoriasis: an exploratory study of symptom prevalence and characteristics. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:39–45. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jobling R, Naldi L. Assessing the impact of psoriasis and the relevance of qualitative research. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1438–1440. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are in the form of audio recordings and transcripts, and are not publicly available due to patient privacy.