Abstract

The butyrogenic capability of Lactobacillus (L.) plantarum is highly dependent on the substrate type and so far not assigned to any specific metabolic pathway. Accordingly, we compared three genomes of L. plantarum that showed a strain-specific capability to produce butyric acid in human cells growth media. Based on the genomic analysis, butyric acid production was attributed to the complementary activities of a medium-chain thioesterase and the fatty acid synthase of type two (FASII). However, the genomic islands of discrepancy observed between butyrogenic L. plantarum strains (S2T10D, S11T3E) and the non-butyrogenic strain O2T60C do not encompass genes of FASII, but several cassettes of genes related to sugar metabolism, bacteriocins, prophages and surface proteins. Interestingly, single amino acid substitutions predicted from SNPs analysis have highlighted deleterious mutations in key genes of glutamine metabolism in L. plantarum O2T60C, which corroborated well with the metabolic deficiency suffered by O2T60C in high-glutamine growth media and its consequent incapability to produce butyrate. In parallel, the increase of glutamine content induced the production of butyric acid by L. plantarum S2T10D. The present study reveals a previously undescribed metabolic route for butyric acid production in L. plantarum, and a potential involvement of the glutamine uptake in its regulation.

Introduction

The genome-scale analysis of health-promoting bacteria is defined as probiogenomics and represents a fundamental approach to investigate their physiological behaviour or foresee potential probiotic and post-biotic features1. Among the intensively studied lactic acid bacteria (LAB) species, Lactobacillus (L.) plantarum is the most versatile one, and it is widely distributed in fermented dairy, sourdough, meat and vegetable foods2,3. L. plantarum is frequently encountered as a natural inhabitant of the human GastroIntestinal Tract (GIT), in which is a transient guest acquirable through the diet4, since it easily adapts its genome in response to the environmental niche requirements by acquiring, mixing or deleting several genomic-lifestyle islands that encode for specific metabolic activities5,6. Thus, L. plantarum genomic flexibility determines a broad range of phenotypes as well as strain-dependent beneficial features once it is introduced as probiotic in the diet, and consequently in the human GIT. Accordingly, the L. plantarum genomic data have been coupled with physiological observations to unravel the genetic determinants responsible for adhesion capability to the intestinal mucosa or immunomodulation of the host7,8. Together with the increasing knowledge over L. plantarum - host interactions, sophisticated bioinformatics tools have been developed using the reference strain L. plantarum WCFS1, including an advanced genome annotation9, genome-based metabolic models10, as well as effective mutagenesis tools11. However, despite those specific tools, there are still numerous uncharacterized pathways in L. plantarum, and they often encompass potential probiotic features.

The production of butyric acid is an example of a strain-dependent metabolic function often described in L. plantarum but, to best of our knowledge, not ascribed to any specific pathway at genomic level yet12–15. The impact of this short chain fatty acid (SCFA) on the intestinal homeostasis is well known, since it is capable to modulate the inflammatory status of the colon, colonic defense barrier, insulin sensitivity, intestinal epithelial permeability, oxidative stress, cryptic stem cells, colonic regulatory cells differentiation16–19 and, above all, it may act in the prevention and remediation of carcinogenesis20,21. In the human gut, butyric acid is the main end-product of intestinal microbial fermentation of undigested dietary fibers and its production is mainly ascribed to members of Firmicutes, such as Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae and Clostridium spp.22.

Accordingly, butyrogenic potential of any Human Intestinal Microbiome (HIM) can be currently determined by targeting the terminal genes of the main butyrate pathways, exploiting metagenomics or amplicon-based sequencing approaches23. These pools of terminal genes, encoding the conversion of butyryl-CoA to butyric acid, encompass several butyryl-CoA transferases (EC numbers: 2.8.3.8/2.8.3.9) and the butyrate kinase (2.7.2.7), which acts after the phosphorylation of butyryl-CoA24,25. Nevertheless, such approach may result reductionist, since it excludes the potential role of other butyrogenic metabolic pathway, such as the fatty acid metabolism, largely exploited by the industrial bioengineering of Escherichia coli 26.

In this context, we have shown in a parallel study how the putative probiotic strains L. plantarum O2T60C, S11T3E and S2T10D27 have potential anti-cancer activity in reason of a strain-specific butyrogenic capability expressed in a culture medium for human cell growth, known as Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (data not published). This medium represents a limited culture substrate for bacterial growth, lacking of recognized pro-butyrate substrates such as the fibers and mainly composed by glucose and glutamine28.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to associate, for the first time, the production of butyric acid in L. plantarum to a defined metabolic pathway. Moreover, we attempted to identify by functional and comparative genomics the potential genetic determinants and bioactive/growth substrates responsible for butyric acid strain-specific production in DMEM culture medium.

Results

Sequencing and comparative genomics reveals two distinct genotypes

The complete genomes of L. plantarum S2T10D, S11T3E and O2T60C were assembled in 92, 58 and 68 scaffolds respectively. Overall, the three L. plantarum strains showed genomes size ranging from 3.17 Mbp (strains S2T10D/S11T3E) to 3.31 Mbp for strain O2T60C (Table 1). Draft genomes were aligned to six reference L. plantarum genomes (WCFS1, P8, 16, JMD1, ZJ316 and ST-III) to calculate the pairwise genetic distances (data not shown). An average distance overall was calculated and resulted to be 0.00856. The scaffolds of the three strains were re-ordered using L. plantarum P8 strain (NC_021224.1) as guide reference, being the one with a genetic distance more similar to the average value, overall calculated. Both unplaced scaffold and putative plasmid genes were placed in the last position of the three de novo anchored genomes, generated by this ordering process. The reconstructed whole genome sequences of L. plantarum S2T10D, L. plantarum S11T3E and L. plantarum O2T60C have been deposited in the GenBank database, under the accession numbers MQNK00000000, MQNL00000000, MPLC00000000, respectively (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

General genomic features and comparative genomics of L. plantarum strains S2T10D, S11T3E and O2T60C, in comparison with the strain P8 (used as guide reference for the re-ordering of the scaffolds) and L. plantarum reference genome WCFS1.

| L. plantarum strains: | S2T10D | S11T3E | O2T60C | P8 | WCFS1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General genomic features | Accession no. | MQNK00000000 | MQNL00000000 | MPLC00000000 | NC_021224 | NC_004567 |

| Genome size, Mbps | 3.17 | 3.17 | 3.31 | 3.25 | 3.35 | |

| N° scaffolds | 92 | 58 | 68 | 8 | 4 | |

| GC, content% | 44.48 | 44.49 | 44.41 | 44.55 | 44.45 | |

| No. of CDS | 3,046 | 3,050 | 3,171 | 3,119 | 3,063 | |

| tRNA genes | 45 | 61 | 65 | 68 | 70 | |

| rRNA genes (complete operons) | 6 (1) | 8 (1) | 11 (1) | 6 (4) | 5 (5) | |

| Transposases | 33 | 34 | 49 | 104 | 36 | |

| Prophage clusters (intact) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 4 (3) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) |

All data reported are available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/.

The putative encoded proteomes vary in relation to the genome sizes (Table 1), harboring up to 3,000 proteins each one. InterProScan identified 2532 (S2T10D), 2546 (S11T3E) and 2660 (O2T60C) genes, with at least one domain (2917, 2971 and 3027 unique IPR domain for S2T10D, S11T3E and O2T60C, respectively). The top 20 SUPERFAMILY domains found in the three genomes, together with those harbored in the reference strain WCFS1 and the guide reference P8, are reported in Supplementary Figure 1. The most abundant protein superfamilies are P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase and “Winged helix” DNA-binding domains in accordance with what observed in the reference genomes of L. plantarum WCFS1 and P8. These domains mainly involve proteins acting in membrane transport (ABC transporter) and regulatory processes. Notably, the profile of O2T60C differs from those of S2T10D and S11T3E in the assignments of the three most abundant domains.

The relative distributions of COG categories in the three strains are similar to those of L. plantarum P8, while they are disproportionate compared to the reference genome of L. plantarum WCFS15, which shows a greater number of proteins involved in the transport/metabolism of carbohydrates and a lower number of mobile genetic elements (Supplementary Figure 2). Concerning the mobile genetic elements, L. plantarum O2T60C possesses more transposase genes compared to S2T10D/S11T3E genomes, and also one additional intact phage cluster, identified by PHASTER tool as Lactobacillus phage Sha 1 (NC_019489). Noticeably, we did not identify CRISPRs motifs along the genomic sequences and only one single CRISPR-associated endonuclease Cas2 was annotated in the S2T10D/S11T3E genomes.

The OrthoMCL29 comparison performed among S2T10D, S11T3E and O2T60C clustered together a total of 8,168 sequences into 2,954 gene families (except singletons), highlighting a core-genome of 2,576 gene families. The same analysis conducted by comparing L. plantatum S2T10D, S11T3E and O2T60C with P-8 and WCSF1 strains proteomes, grouped a total of 13,655 sequences into 3,190 gene families (except singletons), highlighting a core-genome of 2,344 gene families (Supplementary Figure 3).

Phylogenetic analysis

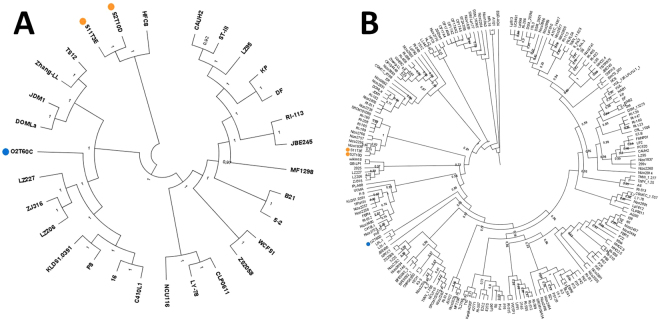

A phylogenetic tree was constructed using nucleotide sequences of L. plantarum genomes, in order to highlight the genetic relation between the three strains with respect to 27 publicly available complete L. plantarum sequenced genomes (Supplementary Table 1). The analysis produced three well-separated clusters (Fig. 1A) and highlighted a pairwise high similarity of S2T10D and S11T3E, which clustered closed to the HCF8 strain. Strain O2T60C clustered in the clade with the LZ227 and LZ206, ZJ316, KLDS1.0391, P8 and P16 strains. All three strains were clearly separated from a third cluster, which included the reference WCFS1 and ST-III.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic trees including the genomes of the three L. plantarum analysed here and (A) other 27 complete genomes of L. plantarum, and (B) all L. plantarum genomes available (including both the complete as well as the unfinished sequences). The tree was constructed with Parsnp (https://github.com/marbl/parsnp), using the whole genome sequence of each selected strain. The strain O2T60C is highlighted by a blue circle, while S11T3E and O2T60C by orange ones. The bootstrap values are reported as a value ranging from 0 to 1.

In addition a second tree was constructed using all the available L. plantarum sequenced genomes, thus including both the complete as well as the unfinished sequences. The analysis (Fig. 1B) highlighted the same high similarity of S2T10D and S11T3E, which clustered closed to some Nizo and RI strains. On the other side, strain O2T60C clustered in the clade with LPL-1 and L31-1 strains.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms observed between O2T60C and butyrogenic strains

Assuming S2T10D/S11T3E and O2T60C as two different genotypes, we used the butyrate-producing strain S2T10D as backbone reference to analyze the number of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) hosted in the core-genomes of the three strains (Table 2). Overall, we observed a high degree of sinteny between S2T10D and S11T3E, with only 15 nsSNPs detected in the genome of S11T3E and hosted by 4 genes (lacL-lacM; brnQ; BBA84_01095). However, PROVEAN analysis did not predict functional damages in the corresponding encoded proteins. The remaining SNPs retrieved in S11T3E generate synonymous mutation (90 SNPs) or are located in the intercistronic regions upstream or downstream the CDS (33 SNPs). On the other hand, 4,840 nsSNPs responsible of missense mutations in the amino acid sequences were detected in 1,598 genes of O2T60C.

Table 2.

Cumulative summary and categorization of SNPs detected in the O2T60C and S11T3E genomes in comparison to the reference S2T10D.

| S2T10D vs: | Synonimous SNPs | nsSNPs | High damage nsSNPs | non-coding SNPs | Total SNPs | No of genes hosting nsSNPS | No of genes hosting dSNPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O2T60C | 12464 | 4774 | 66 | 4544 | 21848 | 1598 | 64 |

| S11T3E | 90 | 15 | 0 | 33 | 138 | 4 | 0 |

Among the dSNPs found in the O2T60C, 66 mutations harbored in 64 genes generate deletion or addition of start/stop codons in each single host CDS, resulting in a functional damage of the encoded protein (Supplementary Table 2). The majority of the genes with high damage SNPs encoded for proteins with unknown function (11 genes), mobile elements (7 genes), proteins involved in the cell envelope biogenesis and outer membrane (11 genes).

Overall gene content differences between O2T60C and butyrogenic strains

By combining the results from OrthoMCL analysis and KO assigned by KASS, we identified two sets of exclusive genes in the genotypes S2T10D/S11T3E and O2T60C, comprising 270 and 136 genes, respectively. Some of these were organized in genomic islands (GIs), which host in turn operons encoding for specific metabolic functions as well as proteins involved in bacteria-host or bacteria-environment interactions (Table 3). Overall, in O2T60C strain we observed unique set of genes that include a noticeable presence of phages, plasmid, transposases-related proteins (overall 43 genes) and elements related to DNA replication, recombination and repair (16 genes), with 43 and 16 genes respectively (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 3.

Compositional features of the major genomic islands (GIs) of discrepancies observed between the genotypes O2T60C and S2T10D/S11T3E.

| Genomes | GIs | Size (kb) | CDS Coordinates* | Overall functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O2T60C | 1 | 26.9 | BBA85_00118 - BBA85_00148 | Molybdopterin cofactor biosynthesis, iron transport, nitrite extrusion, kinase/response regulator system |

| 2 | 16.3 | BBA85_01811 - BBA85_01827 | Inositol uptake/metabolism and regulatory system, Galactilol PTS system | |

| 3 | 13.1 | BBA85_00355 - BBA85_00367 | Galactilol PTS system | |

| 4 | 8.2 | BBA85_00391 - BBA85_00399 | Rhamnose uptake/metabolism and regulatory system | |

| 5 | 2.0 | BBA85_02270 - BBA85_02472 | Iron transport | |

| S2T10D* S11T3E | 6 | 9.1 | BBF95_00141 - BBF95_00152 | Conserved plantaricin operon |

| 7 | 7.9 | BBF95_02519 - BBF95_02524 | Type I restriction-modification system | |

| 8 | 7.6 | BBF95_00632 - BBF95_00638 | EPS and CPS biosynthesis | |

| 9 | 4.9 | BBF95_01179 - BBF95_01183 | EPS and CPS biosynthesis | |

| 10 | 3.3 | BBF95_01848 - BBF95_01846 | Membrane proteins | |

| 11 | 2.0 | BBF95_02607 - BBF95_02609 | Membrane proteins |

Concerning the metabolic functions, only strain O2T60C possesses the complete operon narGHJI, encoding the nitrate reductase enzyme, and its molybdopterin cofactor biosynthesis genes (BBA85_00118 - BBA85_00148). The whole GI 1 enables the anaerobic respiration in L. plantarum by using nitrate and nitrite as electron acceptors9. Other GIs exclusive of O2T60C contain genes for the uptake and metabolism of specific sugars/alcohols, organized in gene cassettes encoding transporters, metabolic enzymes and regulatory proteins6. Among them, we annotated gene cassettes responsible of uptake and utilization of inositol (GI 2) and rhamnose (GI 4), though the latter gene cassette showed a truncation operated by transposases at the regulatory protein DeoR (BBA85_00399; BBA85_01826). Moreover, ABC-transporter of iron complexes (BBA85_02470 - BBA85_02472; BBA85_00118 - BBA85_00120) and the specific PTS systems for the galactitol uptake (BBA85_00358 - BBA85_00360; BBA85_01823 - BBA85_01825) were exclusively hosted in O2T60C genome.

The majority of genes shared by S2T10D and S11T3E encode for mobile genetic elements, for membrane and cell surface proteins, and for proteins with unknown functions, with 91, 43 and 37 genes respectively (Supplementary Table 4). Noticeable, the conserved loci organization of plantaricin regulon was found in this group of genes (GI 6). Moreover, this group of genes hosts two clusters of genes involved in capsular polysaccharides (CPS) and exopolysaccharides (EPS) biosynthesis (GIs 8 and 9), and also GIs encoding for membrane proteins (GIs 10 and 11).

Identification of the metabolic route and triggering factors responsible of butyric acid production

Butyric acid is produced via fatty acid synthase of type II (FASII)

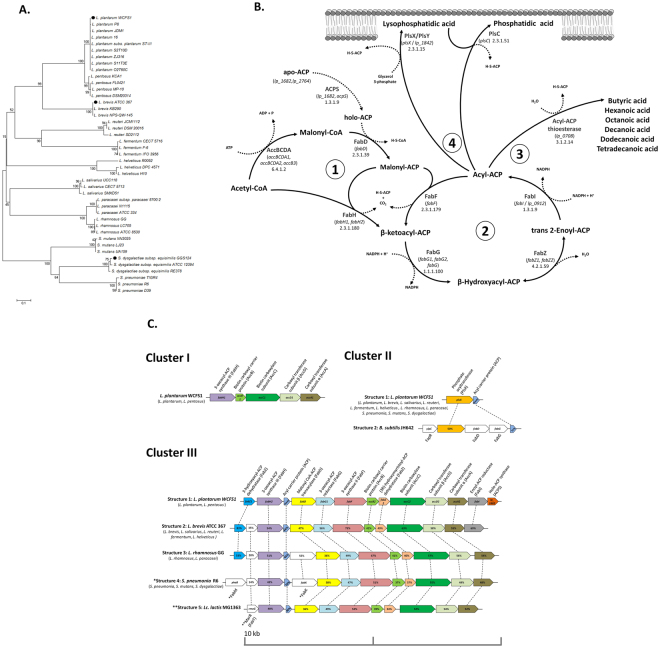

Potential butyrogenic capability of isolates/sequenced genomes and metagenomes of whole communities are commonly inferred by targeting specific key genes that characterize the function, such as those encoding for the final enzymatic reaction in a butyrogenic pathway. As first step of analysis, we targeted the whole pool of terminal genes present in the acetyl-CoA/butyryl-CoA, ɣ-aminobutyrate/succinate, glutarate and lysine pathways, which represent the currently known butyrogenic metabolism of the HIM24. Practically, 521 amino acids sequences (http://img.jgi.doe.gov/) of the genes responsible for the enzymatic conversion of butyryl-CoA to butyric acid (EC numbers 2.8.3.8/2.8.3.9/2.7.2.7) were aligned to the predicted proteomes of S2T1D, S11T3E, O2T60C and the reference strain L. plantarum WCFS1. After the exclusion of these terminal genes and their respective butyrogenic pathways, we proceeded searching for all genes responsible of enzymatic reactions involved in the production of butyric acid (www.brenda-enzymes.org; http://www.genome.jp/kegg/annotation/enzyme.html; https://metacyc.org/). After this second step we identified in the medium-chain acyl-ACP thioesterase (lp_0708) the only possible terminal enzyme capable to produce butyric acid in L. plantarum. Indeed this enzyme, as well as those of L. brevis ATCC 367 and S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis GGS 124, have been previously demonstrated capable to truncate the fatty acid biosynthesis pathway of type II (FASII) in engineered E. coli, releasing butyric acid and other medium chain fatty acids30. The amino acid sequences of the TEs belonging to 12 different species of Gram-positive bacteria were thus aligned. The Neighbor-Joining tree elaborated (Fig. 2A) has shown a high intra-specific homology among the amino acids sequences of TEs, and notably we did not observe for this enzyme any nsSNPs between the non-butyrogenic O2T60C and the strain S2T10D (Table 4).

Figure 2.

(A) Unrooted Neighbour-Joining tree based on the amino acid sequences of 43 acyl-ACP thioesterases (TEs) present in 13 gram positive bacterial species. TEs demonstrated capable to produce butyric acid are marked with black dots30. (B) Schematic representation of the conserved type II fatty acid biosynthesis pathway (FASII) and phosphate acyltransferase system (Pls) in L. plantarum species based on the reference strain L. plantarum WCFS1. Briefly, in the FASII initiation (1) the four separated subunits of acetyl-CoA carboxylase enzyme (Acc) catalyze the formation of malonyl-CoA starting from acetyl-CoA, with the biotin as covalently attached cofactor. Subsequently, the transacylase FabD substitutes the CoA for an acyl carrier protein (ACP), which is previously activated by phosphopantetheinyl-transferase (ACPS). The malonyl-ACP is condensed by FabH to acetyl-CoA, forming the β-ketoacyl-ACP. The β-ketoacyl-ACP enters in the iterative process of fatty acids chain-elongation (2), in which it is reduced by the FabG enzyme and dehydrated, first by FabZ (reversible reaction) and then by FabI (else FabK), producing the first four-carbons chain (C4) acyl-ACP. From this point the elongation process can continue through the dehydration of acyl-ACP carried out by FabF, or may be interrupted by a (3) medium-chain ACP-thioesterase (WP_003645113.), which cleaves the ester bonds and release free fatty acids with a chain length ranging from C4 and C1430. Once elongated up to C1482 the acyl-ACPs are transferred to the cells membrane (4) by acyltransferase (PlsX, PlsY, PlsC). (C) Genetic maps of FASII-Pls related genes in L. plantarum WCFS1 (representative loci organization of L. plantarum and L. pentosus species) and comparison with other Gram positive bacteria loci organizations, represented by the reference strains: L. brevis ATCC 367, L. rhamnosus GG, S. pneumoniae R6, Lc. lactis MG 1363 and B. subtilis JH 642. Species that have the same loci organization of each reference strain are reported in parentheses. Orthologous genes are denoted by the same color and connected by dashed lines while genes not present in L. plantarum are blanks. Proteins encoded are reported above or below the gene locus and the percentage of the amino acids similarity is reported for each homologous protein compared to L. plantarum WCFS1, or otherwise compared to a reference strain marked with asterisks (*).

Table 4.

Complete list of proteins and encoding genes of L. plantarum S2T10D (butyrogenic strain) and L. plantarum O2T60C (non-butyrogenic strain) involved in the FASII-Pls pathway, together with results obtained from SNPs meaning (S2T10D vs. O2T60C) and prediction of the functional impact of mutation by means of PROVEAN.

| Clusters | Proteins | Gene names* | E.C. no | Locus tag | O2T10D vs. S2T10D | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S2T10D (butyrogenic) | O2T60C (non-butyrogenic) | nsSNPs | PROVEAN prediction (cutoff = −2.5) | Amino acids mutations (score) | ||||

| I | 3-oxoacyl-ACP synthase III (FabH) | fabH1 | 2.3.1.180 | BBF95_00504 | BBA85_01856 | 1 | Neutral | |

| Biotin carboxyl carrier protein (AccB) | accB1 | 6.4.1.2 | BBF95_00505 | BBA85_01857 | ||||

| Biotin carboxylase subunit (AccC) | accC1 | 6.4.1.2 | BBF95_00506 | BBA85_01858 | 3 | Neutral | ||

| Carboxyl transferase subunit β (AccD) | accD1 | 6.4.1.2 | BBF95_00507 | BBA85_01859 | 2 | Neutral | ||

| Carboxyl transferase subunit α (AccA) | accA1 | 6.4.1.2 | BBF95_00508 | BBA85_01860 | 3 | Neutral | ||

| II | Phosphate acyltransferase (PlsX) | plsX | 2.3.1._ | BBF95_00619 | BBA85_01666 | |||

| Acyl carrier protein (ACP) | acpA1 | / | BBF95_00620 | BBA85_01667 | ||||

| III | 3-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase (FabZ) | fabZ1 | 4.2.1.59 | BBF95_00945 | BBA85_03004 | |||

| 3-oxoacyl-ACP synthase III (FabH) | fabH2 | 2.3.1.180 | BBF95_00946 | BBA85_03005 | ||||

| Acyl carrier protein (ACP) | acpA2 | / | BBF95_00947 | BBA85_03006 | ||||

| Malonyl CoA-ACP transacylase (FabD) | fabD | 2.3.1.39 | BBF95_00948 | BBA85_03007 | 1 | Neutral | ||

| 3-oxoacyl-ACP reductase (FabG) | fabG1 | 1.1.1.100 | BBF95_00949 | BBA85_03008 | 1 | Neutral | ||

| 3-oxoacyl-ACP synthase II (FabF) | fabF | 2.3.1.179 | BBF95_00950 | BBA85_03009 | ||||

| Biotin carboxyl carrier protein (AccB) | accB2 | 6.4.1.2 | BBF95_00951 | BBA85_03010 | ||||

| (3R)-hydroxymyristoyl-ACP dehydratase (FabZ) | fabZ2 | 4.2.1.59 | BBF95_00952 | BBA85_03011 | ||||

| Biotin carboxylase subunit (AccC) | accC2 | 6.3.4.14 | BBF95_00953 | BBA85_03012 | ||||

| Carboxyl transferase subunit β (AccD) | accD2 | 6.4.1.2 | BBF95_00954 | BBA85_03013 | 2 | Deleterious | Q231K (−3.255) | |

| Carboxyl transferase subunit α (AccA) | accA2 | 6.4.1.2 | BBF95_00955 | BBA85_03014 | ||||

| Enoyl-ACP reductase (FabI) | fabI | 1.3.1.9 | BBF95_00956 | BBA85_03015 | ||||

| Holo-ACP synthase (ACPS) | acps | 2.7.8.7 | BBF95_00957 | BBA85_03016 | 1 | |||

| Acyl-ACP thioesterase | lp_0708 | 3.1.2.14 | BBF95_00554 | BBA85_01904 | ||||

| Biotin carboxyl carrier protein (AccB) | accB3 | 6.4.1.2 | BBF95_00112 | BBA85_02896 | ||||

| 3-oxoacyl-ACP reductase (FabG) | lp_0159 | 1.1.1.100 | BBF95_01809 | BBA85_02754 | ||||

| 3-oxoacyl-ACP reductase (FabG) | fabG2 | 1.1.1.100 | BBF95_01940 | BBA85_00593 | ||||

| Putative enoyl-ACP reductase (FabI2) | lp_0912 | 1.3.1.9 | BBF95_02498 | BBA85_01269 | 2 | Neutral | ||

*genes names are referred to L. plantarum WCFS1.

The FASII pathway located upstream the TE cleaving activity and the phosphate acyltransferase system (Pls) of L. plantarum were schematized in Fig. 2A. Moreover the L. plantarum FASII/Pls structure (i.e. loci organization) were compared with known structures of the 12 different species previously considered and the outgroup species B. subtilis JH 642 (Fig. 2C). Overall, this pathway in L. plantarum species encompasses 26 genes, of which 20 are organized in three operons, here named cluster I, II and III (Fig. 2B). The first cluster (I) harbors genes responsible of the FASII initiation and, among the species considered, is only detectable in L. plantarum and the closest L. pentosus species. Conversely, the structure present in the cluster II (PlsX-Acp) is highly conserved among the species considered, except for the outgroup B. subtilis JH 642 that hosts a thioesterase enzyme FapR, a transcriptional repressor of FASII and Pls genes31,32. The third and widest (~10 kb) cluster showed again a unique structure for L. plantarum/L. pentosus that notably lacks of FabT, a transcriptional repressor belonging to MarR family located upstream the 3-oxacyl-ACP synthase, which has been proven to repress the FASII operon in Streptococcus spp. and Lactococcus lactis and it may likewise act in Lactobacillus spp. that contain it in the same position33–35.

As far as the differences observed between S2T10D and O2T60C are concerned, all genes of this metabolic pathway are highly conserved while, in terms of mutations, the pathway of O2T60C harbors 16 nsSNPs compared to S2T10D. Notably, the mutation Q231K has been predicted deleterious (value of −3.255) for the functionality of the carboxyl transferase subunit β encoding gene located in the cluster III (Table 4).

Glutamine content triggers butyric acid production in DMEM culture media

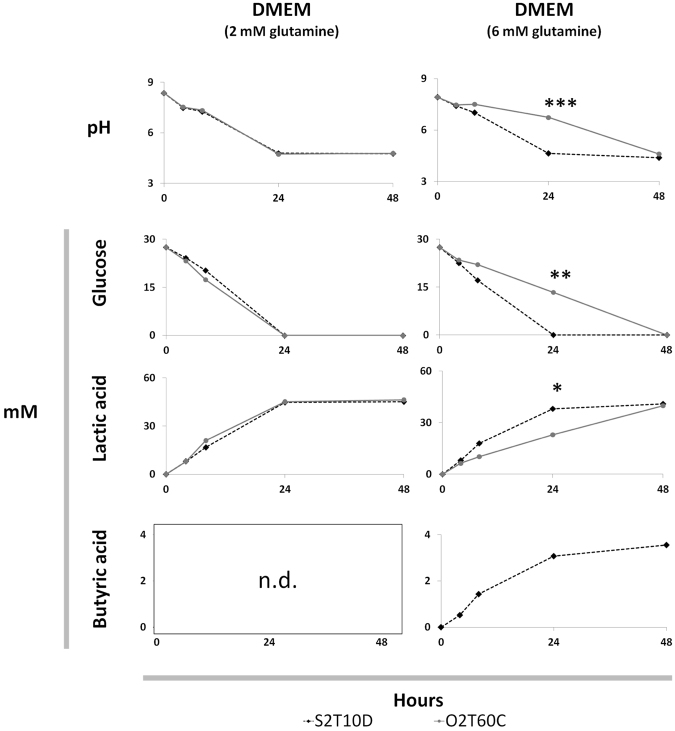

In order to clarify the strain-dependent butyrogenic activity previously observed in high-glutamine supplemented DMEM (6 mM) we cultured the strains O2T6C and S2T10D in this human cells culture medium for 48 hours. In reason of the inhibitory activity of high amount of free amino acid versus lactobacilli36, we reduced the amount of glutamine to 2 mM. In parallel, we inoculated the strains in MRS and PBS, maintaining 0.45% of glucose as the only sugar available (Supplementary Table 5).

The butyric acid was produced only by strain S2T0D once inoculated in the DMEM supplemented with 6 mM of glutamine. In both glutamine concentrations (2 and 6 mM) the O2T60C did not produce butyric acid at all, while in presence of 6 mM of glutamine it suffered a slowdown of the metabolic activities, compared to its behavior in 2 mM of glutamine and to the strain S2T10D dynamics (Fig. 3). Accordingly, in the 6 mM supplemented DMEM the consumption of glucose, lactic acid production and pH variation were significantly different between O2T60C and S2T10D the 24th hour of incubation (p < 0.05). Finally, strains S2T10D and O2T60C showed the same metabolic behavior in MRS and glucose supplemented PBS.

Figure 3.

Variation of pH, glucose, lactic acid and butyric acid contents (mM) recorded during the fermentation of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; 0.45% of glucose) supplemented with 2 and 6 mM of L-glutamine and inoculated with L. plantarum O2T60C and S2T60C. The strains were inoculated at 8.0 ± 0.2 Log CFU and incubated for 48 h at 37 °C. Significant differences between the two strains O2T60C and S2T60D are highlighted with asterisk (T-test or Kolmogorov–Smirnov test; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). Complete dataset of the four fermentation trials is reported in Supplementary Table 5 *n.d. = below the detection limit at all time points for both strains in the presence of 2 mM of L-glutamine.

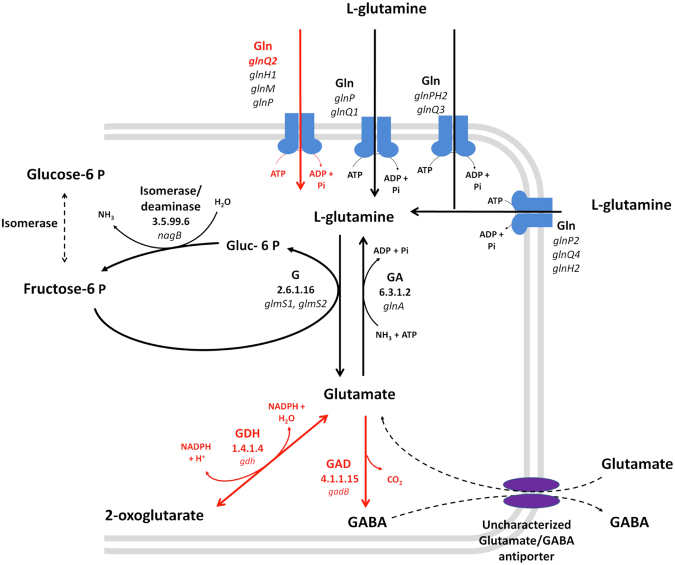

To elucidate the potential genomic-based causes behind the metabolic stress induced by glutamine in L. plantarum O2T60C, the O2T60C enzymes involved in all reactions encompassing glutamine and glutamate were compared to those of L. plantarum S2T10D (Supplementary Figure 6). Overall, O2T60C possess the same number of glutamine-related genes of S2T10D, for a total of 48. Within a pool of 86 nsSNPs observed in O2T60C, the central glutamine metabolism and the ABC transporter host three deleterious mutations responsible of a potential functional damage at enzymatic level. Indeed, we predicted deleterious functional mutations (PROVEAN score below – 2.5) for the amino acid sequences of gnlQ2 gene (mutation P231S), encoding for a subunit of glutamine ABC transporter GlnQHMP, the glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH; mutation D408A) and the glutamate decarboxylase (GAD; V167A) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of glutamine uptake system and glutamine/glutamate central metabolism. Reconstruction was based on the reference strain WCFS1. Gln, Glutamine ABC-transporter; G, Glutamine–fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase; GA, Glutamine synthetase; GDH, Glutamate dehydrogenase; GAD, Glutamate decarboxylase. Genes and relative enzymatic reactions labeled in red are predicted hosting deleterious mutations that may affect functionality (PROVEAN value below – 2.5). The complete list of reactions and genes of S2T10D and O2T60C involved in glutamine uptake and glutamine/glutamate metabolism is reported in Supplementary Table 6.

The subunit GlnQ2 of ABC transporter and GAD host deleterious mutations capable to affect their biological function with a high level of probability, with alignment-based scores of −7.602 and −3.806, respectively37. In accordance with the high level of probability that functional damage may occur, both deleterious mutations observed in GlnQHMP and GAD of O2T60C are not present in the six reference strains WCFS1, JMD1, ST-III, ZJ316, 16 and P8. Interestingly, the GAD is a singleton gene and, if confirmed, this predicted functional deficit cannot be remediated by other copy of the gene.

Discussion

Comparative genomic analysis for L. plantarum strains S2T10D, S11T3E and O2T60C provided herein, confirms the high genomic flexibility and consequent physiological/metabolic versatility of this LAB species which can acquire, substitute or delete genomic regions and related metabolic features in response to the environmental niches5.

Overall, L. plantarum O2T60C was shown to be phylogenetically distant from strains S2T10D/S11T3E and to possess a distinct putative encoded proteome. Firstly, as expected, the genomic islands of divergence existing between O2T60C and S2T10D/S11T3E include mainly mobile genetic elements, such as transposases and prophage regions. Secondly, they include genomic regions known to be hyper-variable in L. plantarum strains isolated from different environments, and represented by gene clusters encoding for bacteriocins production, specific gene cassettes for carbohydrate and alcohol uptake/utilization, CPS/EPS biosynthesis genes and surface proteins2,3. It is noteworthy that O2T60C was isolated from the surface of olives in the final stages of fermentation, while strains S2T10D and S11T3E were recovered in fermentative brine at the early stages, which were previously characterized as two distinct ecological niches with differences in nutritional characteristics, such as types and amount of sugar available38,39.

As far as discrepancies in the metabolic activities, only O2T60C owns the complete genetic cluster enabling the heme-dependent anaerobic respiration9,40,41. The reduction of nitrate and nitrite to ammonia and NO is considered an exclusive metabolic feature of L. plantarum genome within the Lactobacillus genus, and once expressed it confers a strain-selective advantage during food fermentations. Anaerobic respiration may also increase the persistence in human GIT, where menaquinone is easily available and NO produced plays a role as signal molecule by which L. plantarum modulates physiology of GIT41,42. On the other hand, the group of genes exclusively hosted in L. plantarum S2T10D and S11T3E contain among others the conserved plantaricin regulon structure of L. plantarum, consisting of a regulatory operon (plnABCD), plantaricin EF operon (plnEFI) and the transport operon (plnGHSTUVWX)43,44. However, the regulon is devoid of PlnA pheromone and therefore not able to release any antimicrobial peptides45. These findings are in agreement with previous physiological tests, in which S2T10D and S11T3E did not inhibit pathogens by secretion of any proteinaceous compounds27. Regardless from lack of plnA gene, the whole operon plnGHSTUVWX has been demonstrated to be actively involved in the immune modulation of human dendritic cells, by acting on their inflammation status7. The presence and the potential expression of this transport operon in S2T10D/S11T3E, as well as the anaerobic respiratory capability of O2T60C deserve further investigation, to define whether these genomic features determine positive or negative impact in the GIT of the human host. Further, the group of genes absent or structurally damaged in the genome of O2T60C, contains several genes encoding for sortases, LPxTG-like cell wall anchor motif that have a pivotal role in bacterial intestinal colonization/adhesion46,47. However, in vitro experiments performed so far did not show significant and constant differences between adhesion capabilities of O2T60C and the other two strains27.

Besides the comparative genomics of the three strains, we also attributed the production of butyric acid to the complementary activities of the FASII pathway and the multispecies medium-chain acyl-ACP thioesterase (TE), enriching the current knowledge on the metabolic pathways reconstructed in L. plantarum 5,9. Despite the TE of L. plantarum WCFS1 has been demonstrated capable to produce butyric acid in engineered E. coli 30, so far the FASII-TE pathway has never been indicated as the only butyrogenic pathway present in this species. Aligning the TEs of different Gram-positive bacteria, we observed homologies in accordance with the overall phylogenetic distance of the species48,49. Notably, within L. plantarum species the TEs have shown the same amino acid sequences and hence they potentially express the same potentially butyrogenic function. This observation seemed to indicate the upstream FASII pathway as the likely responsible of modulating the butyric production in S2T10D and O2T60C. However, we predicted in the FASII pathway of O2T60C only a single deleterious mutation for the carboxyl transferase subunit β (accD2), which, in reason of the redundancy of this gene, may not determine any severe consequence for the FASII functionality.

Comparing the FASII pathway of different Gram-positive species, we observe a peculiar structure and loci organization of L. plantarum and L. pentosus, which lacks both transcriptional regulators FabT and FapR, respectively involved in the FASII repression of LAB and Gram-positive pathogens like Bacillus subtilis 31–35. The absence of these FASII repressors in L. plantarum/L. pentosus enables us to hypothesize a major role of TE enzymes in the modulation of lipids metabolism and cell membrane structure, by interrupting the fatty acid elongation process in response to external stimuli. Overall, the FASII pathway plays a central role in the adaptation of Gram-positive bacteria to external environment since, in response to nutritional factors available and physic-chemical condition, the cell membrane composition is selectively modified by complex regulatory networks of genes50,51. For instance, the fructooligosaccharides (FOS) has recently been demonstrated capable of altering the membrane fluidity of L. plantarum, acting on the FASII transcriptional patterns52. The same FOS, and the inulin, seem to significantly trigger the butyrogenic capability of L. plantarum 12,13, in accordance with the frequent association between fibers uptake and SCFA produced by the human intestinal microbiota in large intestine53.

However, in our specific case DMEM, like all human cells culture media, lacks of these prebiotics and it is mainly composed by glucose and glutamine. Notably, by increasing the glutamine content from 2 to 6 mM we observed a slowdown in the metabolic activities for the strain O2T60C, while in parallel, the production of butyric acid was elicited in S2T10D. To this regard, the glutamine has recently been correlated with an enhanced production of butyric acid by intestinal microbiota and a modulation of Lactobacillus populations in mice dietary supplemented with L. plantarum 54,55. Interestingly, in the genome of O2T60C three functional mutations were predicted in the glutamine uptake system and its metabolism, which play a central role in the regulation of amino acids catabolism of LAB36,56. The potential dysfunction of the ABC-transporter GlnQHMP cannot significantly impact the uptake of glutamine in reason of the redundancy of these ABC-transporter9. On the other hand, GDH and GAD enzymes are encoded by singletons and are responsible of dehydrogenation and decarboxylation of glutamate respectively. Their potential functional damage may result in a limited cell resistance of the L. plantarum in response to external stimuli, such as low pH57–59. Despite we found an effective correlation between physiological behaviours and SNPs analysis, the regulatory network by which the glutamine induces in parallel the butyric acid production in S2T10D and limit the growth of O2T60C, remains beyond the potentiality of this first comparative genomic study, which however provides strong bases for guiding further omics investigations.

In summary, we identified and characterized for the first time the FASII-TE pathway as the only metabolic route responsible of butyric acid production in L. plantarum species, whereas in parallel we observed in our strains S2T10D and O2T60C a clear involvement of the glutamine in its production.

Materials and Methods

DNA sequencing and genome reconstruction

The genome sequences of L. plantarum strains S2T10D, S11T3E and O2T60C were determined by GenProbio SRL (Parma, Italy) using the Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine (PGM; Life Technologies, USA). Briefly, a genomic library was generated using 10 µg of genomic DNA and an Ion Xpress Plus fragment library kit and employing the Ion Shear chemistry according to the user guide. After dilutions, molecules were used as the templates for clonal amplification on Ion Sphere particles during the emulsion PCR according to the Ion PGM template 400 kit manual. DNA quantitation was performed via library quantitation of DNA standards (Kapa Biosystems). The quality of the amplification was estimated, and the sample was loaded onto an Ion 316 chip and subsequently sequenced using 212 sequencing cycles according to the Ion PGM sequencing 400 kit user guide. This number of sequencing cycles resulted in an average reading length of approximately 400 nucleotides.

Raw reads were analyzed with Scythe (https://github.com/vsbuffalo/scythe) for filtering out contaminant substrings and Sickle (https://github.com/najoshi/sickle), which allows to remove reads with poor quality ends (Q < 30). De novo assembly was performed with the Mira (version 3.4.0) assembler60. Contigs were manually inspected for errors and chimeric contigs, due to overlapping mobile elements, were split. Genome reconstruction of each strain was performed submitting the assembled sequences to the Mauve suite (https://www.sourceware.org/mauve). This kind of reconstruction is a reference guided-ordering of the scaffolds based on iterative alignment steps using a known genome. It does not reconstruct a unique chromosome, but it produced a multi-fasta file with a high-confident scaffold order. To select the best reference genome for the reconstruction, all the publicly available sequenced L. plantarum genomes were, at first, compared with the 3 strains and pairwise genetic similarity values were recorded using the genome-to-genome distance calculator (GGDC 2.0: http://ggdc.dsmz.de/distcalc2.php).

Genome annotation and OrthoMCL analysis

Genomes were structurally annotated using the PROKKA suite61, which uses a collection of annotation procedures (e.g.: Prodigal), to generate coding sequences (CDS), proteins and.gbk files for each analyzed strain. Gene functions were assigned to predicted genes using the HMMER suite (v3.1, http://hmmer.org) adopting the TREMBL bacteria database as refs62, with default parameters, with the exception of sequence E-value (e−10) as well as with InterproScan63 (ver. 5.18-57.0;) against all the available databases (ProSiteProfiles-20.119)64, PANTHER-10.065, Coils-2.2.166, PIRSF-3.0167, Hamap-201511.0268, Pfam-29.069, ProSitePatterns-20.11964, SUPERFAMILY-1.7570, ProDom-2006.171, SMART-7.172, Gene3D-3.5.073 and TIGRFAM-15.074. Additional information on metabolic pathways was highlighted using the KASS tool75, adopting the bidirectional best-hit default mode, against all known enzymes of L. plantarum species. COG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups) annotation was conducted using WebMGA76. Prediction of phage clusters was carried out with PHASTER77.

The annotated proteomes of S2T10D, S11T3E and O2T60C were used to conduct an OrthoMCL29 analysis for identifying common and distinctive orthologues sets. In addition, an OrthoMCL analysis was conducted on S2T10D, S11T3E and O2T60C with P8 and JDM1 strains proteomes.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis of the L. plantarum strains was conducted using Parsnp78, a rapid core genome multi-alignment algorithm freely available (https://github.com/marbl/parsnp). The genome sequences of 27 fully assembled L. plantarum strains were downloaded from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/MICROBES/microbial_taxtree.html) and aligned together with O2T60D, S11T3E and S2T10D, using the WCFS1 strain as reference (Fig. 1). The phylogenetic tree was generated using FigTree (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree).

Analysis of single nucleotides polymorphisms (SNPs)

Raw reads of the strains O2T60D and S11T3E were back-aligned to the S2T10D genome, which was selected as the reference in relation to the comparative analysis and its butyrogenic capability in DMEM. The alignment was performed with Burrows-Wheeler Aligner program (BWA79) and ‘mem’ command, with default parameters. The BAM files were processed and adapted for SNP calling program with SAMtools mpileup80, using default parameters with the exclusion of minimum mapping quality equal to 25 and filtering ambiguous read mapping. Results were filtered taking into account two parameters: the SNPs call quality and depth. SNPs having mapping quality lower than 20 were removed. In addition we set as lower limit of mapping depth a value of 8 and the upper limit was set to 200, 70 and 50 for O2T60C, S11T3E and S2T10D, respectively.

Identified variants of O2T60C and S11T3E compared to S2T10D were analyzed using SNPeff (http://snpeff.sourceforge.net/) and classified into four classes: (i) non-coding SNPs, for the variants located outside the CDS; (ii) synonymous SNPs, for variants in CDS, which do not modify the amino acid sequence, (iii) non-synonymous SNPs (nsSNPs), for variants in CDS, which modify amino acid sequence and (iv) deleterious SNPs (dSNPs) which generate, frameshifts, gaining or loss of stop and start codons, causing functional deleterious mutations in the encoded proteins81. The nsSNPs, in genes belonging to pathways of interest, were also analyzed with PROVEAN (Protein Variation Effect Analyzer algorithm), which predicts the functional impact for all classes of protein sequence variation, such a single amino acid substitution, insertion, deletion and multiple substitution. The score threshold used was set to −2.537.

Research of candidate genes responsible of butyric acid production in L. plantarum species

A total of 521 protein sequences belonging to butyrate kinase (Buk), butyryl-CoA transferase (But, AtoA, Atod, 4Hbt) and alternative –CoA transferase were acquired from metagenomic database (http://img.jgi.doe.gov/) of butanoate pathways present in bacteria24 and aligned with the genomes of S2T10D, S11T3E, O2T60C and the reference L. plantarum WCFS1 by BlastP, using default parameters. Candidate orthologous genes were selected considering a minimum of 30% identity over at least 80% of both protein lengths, as filtering threshold. For each of the searched genes (521), if the blastP produced an under threshold score, the orthologous protein was considered absent from the analyzed genome.

Moreover, the presence of all known genes responsible of butyric acid production were manually checked in the genomes by referring to the main public available databases (www.brenda-enzymes.org; http://www.genome.jp/kegg/annotation/enzyme.html; https://metacyc.org/).

Growth dynamics in different substrates

All materials were provided from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA), unless otherwise stated. The L. plantarum strains were routinely cultivated in Man Rogosa Sharpe (MRS) and Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) culture broths (Lab M, Heywood, Lancashire, UK). Stock bacterial cultures were kept at −80 °C with 20% of glycerol. Before performing the physiological tests, a single fresh colony of each bacterial strain was inoculated in the appropriate culture broth, grown overnight and then added at ratio 1:100 in new fresh broth. This suspension was grown until the bacteria reached early-stationary phase (18 h), and thus used for the physiological tests (working culture). The initial concentration of each working culture was determined by optical density (OD) at 630 nm with ELx880 microtiter plate reader (Savatec, Turin, Italy). All the bacterial suspensions were set to the same initial count using an internal standard curve.

The working culture of each strain was washed twice in Ringer’s solution and inoculated at 8.0 ± 0.2 Log CFU mL−1 in four different culture broths: (A) Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) with 0.45% of glucose; (B) Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 2 mM of L-glutamine and 0.45% of glucose; (C) Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 6 mM of L-glutamine and 0.45% of glucose; (D) modified MRS (mMRS) medium (10 g L−1 of bacteriological peptone; 8 g L−1 of soy peptone; 10 g L−1 of yeast extract; 1 mL L−1 of tween-80; 2 g L−1 of K2PO4; 2 g L−1 of triammonium citrate; 0.2 g L−1 of MgSO4) with 0.45% of glucose as only sugar available.

Inoculated culture broths (40 mL) were incubated in 50 mL centrifuge tube for 48 hours at 37 °C, with periodic shaking. Samples (4 mL) were taken after 4 h (early exponential phase), 8 h (exponential phase), 24 h (stationary phase) and 48 h (late stationary/decline phase), and the microbiological enumeration was performed by CFU method. Samples were centrifuged (14 000 × g for 10 minutes), filtered (0.2 µm cellulose acetate) and cell free supernantants (CFS) were kept at −20 °C until the analysis of organic acids and sugars were performed. CFS pH was measured at each sampling point using a pH meter (Crison, Modena, Italy).

HPLC analysis

Organic acids (citric, pyruvic, lactic, acetic, butyric and propionic) and sugars (lactose, glucose and galactose) were determined by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The HPLC system (Thermo Finnigan Spectra System, San Jose, USA) was equipped with an isocratic pump (P4000), a multiple autosampler (AS3000) fitted with a 20 µL loop, a UV detector (UV100) set at 210 and a refractive index detector RI-150. For the organic acid the analyses were performed isocratically, at 0.8 ml min−1 of a 0.013 N H2SO4 as mobile phase at 60 °C, with a 300 × 7.8 mm i.d.cation exchange column (Aminex HPX-87H) at 60 °C equipped with a Cation H+ Microguard cartridge (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, USA). For the sugars, the analyses were performed isocratically, at 1 ml min−1 of H2O as mobile phase, with a 300 × 7.8 mm i.d.cation exchange column (Aminex HPX-87P) at 60 °C equipped with a Carbo-P Microguard cartridge (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, USA). The data treatments were carried out using the Chrom QuestTM chromatography data system (ThermoQuest Corporation, San Jose, USA). Analytical grade reagents (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) were used.

Data availability statement

The data reported in the manuscript are publically available.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The research project was financed by the University of Turin, Italy (Project ORTO11HEXP: Probiotic potential of ecotypes of lactic acid bacteria isolated from artisanal fermented products). The authors would like to thank Professor Marco Ventura for the fruitful suggestions and help in the first stage of this study.

Author Contributions

C.B. wrote the main manuscript text and performed the experiments, A.A. and L.B. performed the bioinformatics analyses of the genomic data, A.G. and M.B. performed the experiments, L.C. and K.R. designed and financed the study. All authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-16186-8.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ventura M, et al. Genome-scale analyses of health-promoting bacteria: probiogenomics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:61–71. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siezen RJ, et al. Phenotypic and genomic diversity of Lactobacillus plantarum strains isolated from various environmental niches. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;12:758–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molenaar D, et al. Exploring Lactobacillus plantarum genome diversity by using microarrays. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:6119–6127. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.17.6119-6127.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vesa T, Pochart P, Marteau P. Pharmacokinetics of Lactobacillus plantarum NCIMB 8826, Lactobacillus fermentum KLD, and Lactococcus lactis MG 1363 in the human gastrointestinal tract. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000;14:823–828. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleerebezem M, et al. Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:1990–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337704100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siezen RJ, van Hylckama Vlieg JET. Genomic diversity and versatility of Lactobacillus plantarum, a natural metabolic engineer. Microb. Cell Fact. 2011;10(Suppl 1):S3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-S1-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meijerink M, et al. Identification of genetic loci in Lactobacillus plantarum that modulate the immune response of dendritic cells using comparative genome hybridization. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Z, et al. Expanding the biotechnology potential of lactobacilli through comparative genomics of 213 strains and associated genera. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8322. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teusink B, et al. In silico reconstruction of the metabolic pathways of Lactobacillus plantarum: Comparing predictions of nutrient requirements with those from growth experiments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:7253–7262. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7253-7262.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Notebaart RA, et al. Accelerating the reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;10:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambert JM, Bongers RS, Kleerebezem M. Cre-lox-based system for multiple gene deletions and selectable-marker removal in Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:1126–1135. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01473-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nazzaro F, Fratianni F, Orlando P, Coppola R. Biochemical traits, survival and biological properties of the probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum grown in the presence of prebiotic inulin and pectin as energy source. Pharmaceuticals. 2012;5:481–492. doi: 10.3390/ph5050481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosch M, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum CECT 7527, 7528 and 7529: probiotic candidates to reduce cholesterol levels. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014;94:803–809. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pessione A, Lo Bianco G, Mangiapane E, Cirrincione S, Pessione E. Characterization of potentially probiotic lactic acid bacteria isolated from olives: Evaluation of short chain fatty acids production and analysis of the extracellular proteome. Food Res. Int. 2015;67:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.11.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ozcelik S, Kuley E, Ozogul F. Formation of lactic, acetic, succinic, propionic, formic and butyric acid by lactic acid bacteria. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2016;73:536–542. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.06.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamer HM, et al. Review article: The role of butyrate on colonic function. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;27:104–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaiko GE, et al. The colonic crypt protects stem cells from microbiota-derived metabolites. Cell. 2016;167:1708–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao Z, et al. Butyrate Improves Insulin Sensitivity and Increases Energy Expenditure in Mice. Diabetes. 2010;58:1–14. doi: 10.2337/db08-1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furusawa Y, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504:446–450. doi: 10.1038/nature12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davie JR. Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity by butyrate. J. Nutr. 2003;133:2485S–2493S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.7.2485S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruemmele FM, et al. Butyrate mediates Caco-2 cell apoptosis via up-regulation of pro-apoptotic BAK and inducing caspase-3 mediated cleavage of poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:729–735. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guilloteau P, et al. From the gut to the peripheral tissues: the multiple effects of butyrate. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2010;23:366–384. doi: 10.1017/S0954422410000247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Filippis, F. et al. High-level adherence to a Mediterranean diet beneficially impacts the gut microbiota and associated metabolome. Gut gutjnl-2015-309957 0:1–10. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309957(2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Vital M, Howe AC, Tiedje JM. Revealing the bacterial butyrate synthesis pathways by analyzing (meta) genomic data. MBio. 2014;5:1–11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00889-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esquivel-Elizondo S, Ilhan ZE, Garcia-Peña I, Krajmalnik-Brown R. Insights into butyrate production in a controlled fermentation system via gene predictions. mSystems. 2017;2:1–13. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00051-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dhamankar H, Tarasova Y, Martin CH, Prather KLJ. Engineering E. coli for the biosynthesis of 3-hydroxy-γ-butyrolactone (3HBL) and 3,4-dihydroxybutyric acid (3,4-DHBA) as value-added chemicals from glucose as a sole carbon source. Metab. Eng. 2014;25:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Botta C, Langerholc T, Cencič A, Cocolin L. In vitro selection and characterization of new probiotic candidates from table olive microbiota. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin A, Agrawal P. Glutamine decomposition in DMEM: Effect of ph and serum concentration. Biotechnol. Lett. 1988;I:695–698. doi: 10.1007/BF01025284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jing F, et al. Phylogenetic and experimental characterization of an acyl-ACP thioesterase family reveals significant diversity in enzymatic specificity and activity. BMC Biochem. 2011;12:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-12-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schujman GE, de Mendoza D. Regulation of type II fatty acid synthase in Gram-positive bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2008;11:148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez MA, et al. A novel role of malonyl-ACP in lipid homeostasis. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3161–3167. doi: 10.1021/bi100136n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Y-J, Rock CO. Transcriptional regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;59:551–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eckhardt TH, Skotnicka D, Kok J, Kuipers OP. Transcriptional regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis in Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:1081–1089. doi: 10.1128/JB.02043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faustoferri RC, et al. Regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis by the global regulator CcpA and the local regulator FabT in Streptococcus mutans. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2015;30:128–146. doi: 10.1111/omi.12076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernández M, Zúñiga M. Amino acid catabolic pathways of lactic acid bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;32:155–183. doi: 10.1080/10408410600880643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi Y, Chan AP. PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2745–2747. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cocolin L, et al. NaOH-Debittering induces changes in bacterial ecology during table olives fermentation. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Botta C, Cocolin L. Microbial dynamics and biodiversity in table olive fermentation: culture-dependent and -independent approaches. Front. Microbiol. 2012;3:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lechardeur D, et al. Using heme as an energy boost for lactic acid bacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2011;22:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brooijmans RJW, De Vos WM, Hugenholtz J. Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 electron transport chains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:3580–3585. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00147-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tiso M, Schechter AN. Nitrate reduction to nitrite, nitric oxide and ammonia by gut bacteria under physiological conditions. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diep DB, Johnsborg O, Risøen PA, Nes IF. Evidence for dual functionality of the operon plnABCD in the regulation of bacteriocin production in Lactobacillus plantarum. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;41:633–644. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diep DB, Straume D, Kjos M, Torres C, Nes IF. An overview of the mosaic bacteriocin pln loci from Lactobacillus plantarum. Peptides. 2009;30:1562–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cho GS, Huch M, Hanak A, Holzapfel WH. & Franz, C. M. a P. Genetic analysis of the plantaricin EFI locus of Lactobacillus plantarum PCS20 reveals an unusual plantaricin E gene sequence as a result of mutation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010;141:S117–S124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang B, et al. Comparative genome-based identification of a cell wall- anchored protein from Lactobacillus plantarum increases adhesion of Lactococcus lactis to human epithelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1–12. doi: 10.1038/srep14109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Remus DM, et al. Impact of Lactobacillus plantarum sortase on target protein sorting, gastrointestinal persistence, and host immune response modulation. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:502–509. doi: 10.1128/JB.01321-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Claesson MJ, van Sinderen D, O’Toole PW. Lactobacillus phylogenomics - Towards a reclassification of the genus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008;58:2945–2954. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65848-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Makarova K, et al. Comparative genomics of the lactic acid bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15611–15616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607117103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y-M, Rock CO. Membrane lipid homeostasis in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:222–233. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murínová, S. & Dercová, K. Response mechanisms of bacterial degraders to environmental contaminants on the level of cell walls and cytoplasmic membrane. 2014 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Chen C, Zhao G, Chen W, Guo B. Metabolism of fructooligosaccharides in Lactobacillus plantarum ST-III via differential gene transcription and alteration of cell membrane fluidity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81:7697–7707. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02426-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mowat AM, Agace WW. Regional specialization within the intestinal immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:667–685. doi: 10.1038/nri3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ren W, et al. Dietary l-glutamine supplementation modulates microbial community and activates innate immunity in the mouse intestine. Amino Acids. 2014;46:2403–2413. doi: 10.1007/s00726-014-1793-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhong Y, Nyman M. Prebiotic and synbiotic effects on rats fed malted barley with selected bacteria strains. Food Nutr. Res. 2014;58:1–8. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v58.24848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dai ZL, et al. L-Glutamine regulates amino acid utilization by intestinal bacteria. Amino Acids. 2013;45:501–512. doi: 10.1007/s00726-012-1264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Su MS, Schlicht S, Gänzle MG. Contribution of glutamate decarboxylase in Lactobacillus reuteri to acid resistance and persistence in sourdough fermentation. Microb. Cell Fact. 2011;10(Suppl 1):S8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-S1-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yunes RA, et al. GABA production and structure of gadB/gadC genes in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains from human microbiota. Anaerobe. 2016;42:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siragusa S, et al. Disruption of the gene encoding glutamate dehydrogenase affects growth, amino acids catabolism and survival of Lactobacillus plantarum UC1001. Int. Dairy J. 2011;21:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2010.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chevreux B, et al. Using the miraEST assembler for reliable and automated mRNA transcript assembly and SNP detection in sequenced ESTs. Genome Res. 2004;14:1147–1159. doi: 10.1101/gr.1917404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D204–212 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Jones P, et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sigrist CJA, et al. New and continuing developments at PROSITE. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D344–347. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mi H, Muruganujan A, Thomas PD. PANTHER in 2013: modeling the evolution of gene function, and other gene attributes, in the context of phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D377–386. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science. 1991;252:1162–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu CH, et al. PIRSF: family classification system at the Protein Information Resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D112–114. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pedruzzi I, et al. HAMAP in 2015: updates to the protein family classification and annotation system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D1064–1070. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Punta M, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D290–301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Lima Morais DA, et al. SUPERFAMILY 1.75 including a domain-centric gene ontology method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D427–434. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bru C, et al. The ProDom database of protein domain families: more emphasis on 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D212–215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Letunic I, Doerks T, Bork P. SMART 7: recent updates to the protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D302–305. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lees J, et al. Gene3D: a domain-based resource for comparative genomics, functional annotation and protein network analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D465–471. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Haft DH, et al. TIGRFAMs and Genome Properties in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. KAAS: An automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:182–185. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu S, Zhu Z, Fu L, Niu B, Li W. WebMGA: a customizable web server for fast metagenomic sequence analysis. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:444. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arndt D, et al. PHASTER: a better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:1–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Treangen TJ, Ondov BD, Koren S, Phillippy AM. The Harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol. 2014;15:524. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cingolani P, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff. Fly (Austin). 2012;6:80–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Garmasheva I, Vasyliuk O, Kovalenko N, Ostapchuk A, Oleschenko L. Intraspecies cellular fatty acids heterogeneity of Lactobacillus plantarum strains isolated from fermented foods in Ukraine. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2015;61:283–292. doi: 10.1111/lam.12454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data reported in the manuscript are publically available.