Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV), dengue virus (DENV) and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) belong to the family Flaviviridae. Their viral particles have the envelope composed of viral proteins and a lipid bilayer acquired from budding through the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The phospholipid content of the ER membrane differs from that of the plasma membrane (PM). The phospholipase A2 (PLA2) superfamily consists of a large number of members that specifically catalyse the hydrolysis of phospholipids at a particular position. Here we show that the CM-II isoform of secreted PLA2 obtained from Naja mossambica mossambica snake venom (CM-II-sPLA2) possesses potent virucidal (neutralising) activity against HCV, DENV and JEV, with 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of 0.036, 0.31 and 1.34 ng/ml, respectively. In contrast, the IC50 values of CM-II-sPLA2 against viruses that bud through the PM (Sindbis virus, influenza virus and Sendai virus) or trans-Golgi network (TGN) (herpes simplex virus) were >10,000 ng/ml. Moreover, the 50% cytotoxic (CC50) and haemolytic (HC50) concentrations of CM-II-sPLA2 were >10,000 ng/ml, implying that CM-II-sPLA2 did not significantly damage the PM. These results suggest that CM-II-sPLA2 and its derivatives are good candidates for the development of broad-spectrum antiviral drugs that target viral envelope lipid bilayers derived from the ER membrane.

Introduction

Cellular membrane compartments can be categorised into two groups; the first group consists of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), nuclear envelope, lipid droplets and cis-Golgi (ER-NE-cis-Golgi lipid territory) and the second group consists of the trans-Golgi, plasma membrane (PM) and endosomes (trans-Golgi-PM-EE membrane territory)1–3. The ER-NE-cis-Golgi membranes have lipid packing defects, whereas the trans-Golgi-PM-EE membranes show tight packing of phospholipids3. Additionally, the phospholipid contents of the ER-NE-cis-Golgi membranes differ from those of the trans-Golgi-PM-EE membranes. Enveloped viruses acquire their envelope lipid bilayers from host cellular membranes4. Consequently, the phospholipid contents of viruses budding through the ER-NE-cis-Golgi membranes differ from those of viruses budding through the trans-Golgi-PM-EE membranes5–7. Moreover, the physicochemical characteristics, such as thickness and sturdiness, differ between the ER-NE-cis-Golgi and the trans-Golgi-PM-EE membranes8,9. Moreover, the sensitivity to hydrolysis by the secreted phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) enzyme has been reported to differ depending on the lipid composition and overall structure10.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV), dengue virus (DENV), Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) and yellow fever virus (YFV), which belong to the family Flaviviridae, bud through the ER membrane to acquire their envelopes11–13. Conversely, influenza A virus (FLUAV) buds through the PM14, and its phospholipid content differs from that of DENV5,6. sPLA2 obtained from a venomous snake was reported to possess potent virucidal (neutralising) activity against DENV and YFV by disrupting the viral envelope lipid bilayers15,16. Human sPLA2 also shows virucidal activity against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)17, which is known to bud through the PM18. Moreover, sPLA2s obtained from the venom of bees and another snake (Naja mossambica mossambica) were reported to inhibit the entry of HIV into host cells without disrupting the viral envelope19. While examining plant and animal substances for their neutralising activity against HCV20,21, we became interested in testing a number of sPLA2s from different sources regarding the specificity against different viruses.

Members of the large sPLA2 family show highly diverse sequence variation and functional characteristics and can be divided into 10 groups and 18 subgroups22. sPLA2 obtained from N. m. mossambica venom belongs to subgroup IA and is further subdivided into at least 6 isoforms, including CM-I, -II and –III23–26. Subgroup IB includes the pancreatic sPLA2s of humans, bovines and porcines. Groups III and XIV include honeybee venom sPLA2 and bacterial sPLA2, respectively. In the present study, we examined the possible virucidal activity of those sPLA2s against a panel of viruses. We found that the sPLA2 CM-II isoform from N. m. mossambica (CM-II-sPLA2) showed potent virucidal activity against HCV, DENV and JEV.

Results

CM-II-sPLA2 possesses potent virucidal activity against HCV, DENV and JEV, which bud through the ER membrane, but not against other viruses that bud through the PM

First, we tested the possible direct virucidal activity of CM-II-sPLA2 (UniProtKB-P00603 [PA2B2_NAJMO]) against infectious particles of a panel of viruses. Each virus was incubated with various concentrations of CM-II-sPLA2 or medium as a control at 37 °C for 1 h and then inoculated onto Huh7it-1 cells. After 1 h of virus adsorption, the residual virus was removed by washing the cells with medium and the cells were cultured for 24 h. The cells were subjected to fluorescent antibody (FA) staining with respective antiviral antibodies to determine the number of virus-infected cells, which represented the inoculum’s viral titres (cell-infecting units [CIU]/ml). In some experiments, a plaque assay and 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assay were performed to determine the viral titres of the inocula (plaque-forming units [PFU]/ml and TCID50/ml, respectively). The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated based on the percent reduction of the initial viral titre.

The results demonstrated that CM-II-sPLA2 efficiently neutralised the infectivity of HCV, DENV and JEV, with 50%-inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of 0.036 ng/ml (0.003 nM), 0.31 ng/ml (0.023 nM) and 1.34 ng/ml (0.10 nM), respectively (Table 1). The dose-dependent inhibition of the viruses by CM-II-sPLA2 is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. HCV, DENV and JEV belong to the family Flaviviridae and are known to bud through the ER membrane11–13. Conversely, CM-II-sPLA2 even at a dose of 10,000 ng/ml did not exert significant virucidal activity against Sindbis virus (SINV; Togaviridae)27, influenza A virus (FLUAV; Orthomyxoviridae) and Sendai virus (SeV; Paramyxoviridae)28, which are known to bud through the PM, or herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1; Herpesviridae), which buds through the trans-Golgi network (TGN)29. Vesicular stomatitis New Jersey virus (VSNJV; Rhabdoviridae), which also buds through the PM30, showed weak sensitivity to CM-II-sPLA2, with an IC50 value of 2,300 ng/ml. The weak CM-II-sPLA2 sensitivity of VSNJV compared to the insensitivity of SINV, FLUAV and HSV-1 could be attributable to the bullet-shape configuration of VSNJV, which might harbour lipid packing defects at the bottom edge of the bullet-shape particles. CM-II-sPLA2 inhibited HIV infection with an IC50 of 5.4 ng/ml. This result is consistent with a previous observation that sPLA2 obtained from bee and snake venoms inhibited HIV entry into host cells without disrupting the HIV particles19.

Table 1.

Virucidal activity of CM-II-sPLA2 against different viruses.

| Virus | Family | Site of virus budding | IC50 (ng/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCV | Flaviviridae | ER | 0.036 ± 0.004 |

| DENV | Flaviviridae | ER | 0.31 ± 0.07 |

| JEV | Flaviviridae | ER | 1.34 ± 0.21 |

| MERS-CoV | Coronaviridae | ERGIC | 10,000 |

| SINV | Togaviridae | PM | >10,000 |

| FLUAV | Orthomyxoviridae | PM | >10,000 |

| SeV | Paramyxoviridae | PM | >10,000 |

| VSNJV | Rhabdoviridae | PM | 2,300 ± 1,333 |

| HIV-1 | Retroviridae | PM | 5.4 |

| HSV-1 | Herpesviridae | TGN | >10,000 |

| EMCV | Picornaviridae | (Non-enveloped) | >10,000 |

| CV-B3 | Picornaviridae | (Non-enveloped) | >10,000 |

Data are presented as the average ± SEM (n = 3 to 5).

We also tested Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), which is a member of family Coronaviridae that is known to bud through the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC)31. The ERGIC constitutes part of the ER-NE-cis-Golgi territory and therefore is considered to have similar characteristics with the ER. Rather unexpectedly, we found that CM-II-sPLA2 exerted only marginal, if any, virucidal activity against MERS-CoV, with an IC50 of 10,000 ng/ml. We assume that the exceptionally large petal-shaped spikes that project approximately 20 nm from the virion envelope, which is a characteristic feature of members of Coronaviridae 31, interfere with the access of CM-II-sPLA2 to the envelope lipid bilayer. Alternatively, a dose-dependent inhibition pattern (see panel (d) in Supplementary Fig. S1) may imply the possibility that there are two groups of MERS-CoV particles: one that is sensitive to 100 ng/ml of CM-II-sPLA2 and another that is resistant to 10,000 ng/ml of CM-II-sPLA2. The latter group may represent viral particles that have budded through the PM, as reported previously32. Further studies are needed to elucidate the issue.

As expected, CM-II-sPLA2 did not neutralize the infectivity of encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) and coxsackievirus B3 (CV-B3), which belong to family Picornaviridae and do not possess envelopes33, even at the 10,000 ng/ml dose.

CM-II-sPLA2 does not inhibit viral replication of HCV and DENV when added to the cells after viral entry

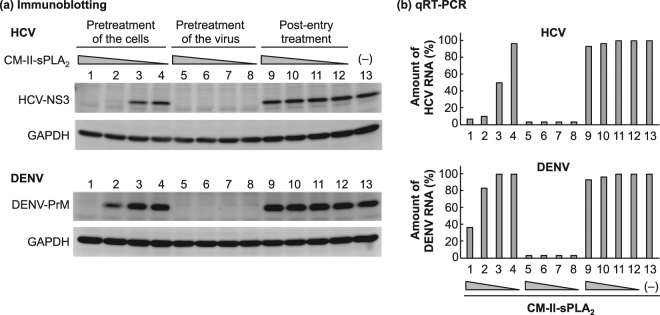

Time-of-addition experiments were performed to examine whether CM-II-sPLA2 inhibited viral replication after the virus entered the host cells. The results showed that post-inoculation (post-entry) treatment of HCV- and DENV-infected cells with CM-II-sPLA2 (1 to 1,000 ng/ml) for 24 h did not reduce the number of infected cells (see Supplementary Table S1). We examined viral protein synthesis and RNA replication in the infected cells under the same experimental conditions. The results demonstrated that whereas pretreatment of the virus with CM-II-sPLA2 at a dose as low as 1.0 ng/ml almost completely inhibited HCV and DENV infection, post-entry treatment of virus-infected cells with CM-II-sPLA2 even at the 1,000 ng/ml dose did not inhibit viral protein synthesis (Fig. 1a) or RNA replication (Fig. 1b). Notably, pretreatment of cells with CM-II-sPLA2 at 100 and 1,000 ng/ml doses prior to viral inoculation resulted in substantial inhibition of viral replication. This result is consistent with the result shown in Supplementary Table S1. Determining whether CM-II-sPLA2 that bound to (or was taken up by) the cells was released into the medium during viral inoculation to neutralise the infectivity of the inoculum or whether CM-II-sPLA2 treatment induced downregulation of the viral receptor(s) and/or upregulation of the antiviral status in the cells requires further investigation. In any case, these results confirmed the potent virucidal activity of CM-II-sPLA2 against HCV and DENV.

Figure 1.

Time-of-addition experiments using CM-II-sPLA2 against HCV and DENV. (a) Immunoblotting analysis. The HCV NS3 (upper panel) and DENV PrM (lower panel) expression levels were examined by immunoblotting. (i) Pretreatment of the cells: Huh7it-1 cells were treated with decreasing concentrations of CM-II-sPLA2 (1,000, 100, 10 and 1 ng/ml) for 1 h. Then, the cells were inoculated with HCV or DENV in the absence of CM-II-sPLA2 for another 1 h and cultured for 24 h in the absence of CM-II-sPLA2. (ii) Pretreatment of the virus: HCV and DENV were incubated with CM-II-sPLA2 for 1 h, and the mixtures were inoculated onto Huh7it-1 cells. After 1 h, the cells were cultured for 24 h in the absence of CM-II-sPLA2. (iii) Post-entry treatment: Huh7it-1 cells were inoculated with HCV or DENV in the absence of CM-II-sPLA2. After 1 h, the cells were cultured for 24 h in the presence of CM-II-sPLA2. (–), Untreated control. The full-length gels and blots are shown in Supplementary Figs S2 and S3. (b) qRT-PCR analysis. The HCV RNA (upper panel) and DENV RNA (lower panel) levels in cells prepared under the same conditions described in (a) were quantified by qRT-PCR. (–), Untreated control. Data are presented as the percentage of the untreated control.

CM-II-sPLA2 does not mediate in vitro cytotoxicity or haemolytic activity

We also tested the cytotoxicity and haemolytic activity of CM-II-sPLA2. Uninfected Huh7it-1 cells were incubated with various concentrations of CM-II-sPLA2 at 37 °C for 24 h. Cell viability was determined using a WST-1 assay and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release test, and the 50% cytotoxic concentrations (CC50) were calculated. The haemolysis assay was performed by incubating human red blood cells (RBCs) with CM-II-sPLA2 at 37 °C for 1 h, and the 50% haemolytic concentration (HC50) was calculated. CM-II-sPLA2 even at the 10,000 ng/ml dose mediated only marginal, if any, cytotoxicity or haemolytic activity (Table 2). The selectivity indices (CC50/IC50) of CM-II-sPLA2 against HCV and DENV were >270,000 and >32,000, respectively.

Table 2.

Virucidal activity of various sPLA2s from different sources.

| sPLA2 | IC50 (ng/ml) | CC50 or HC50 (ng/ml) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV | DENV | JEV | SINV | FLUAV | SeV | VSNJV | HSV-1 | WST-1 | LDH | Haemolysis | |

| CM-II-sPLA2 | 0.036a) | 0.31a) | 1.34a) | >10,000a) | >10,000a) | >10,000a) | 2,300a) | >10,000a) | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| A. mellifera | 117 ± 43 | 183 ± 38 | 49 ± 13 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| S. violaceoruber | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| Bovine pancreas | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

| Porcine pancreas | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 |

Data are presented as the average ± SEM (n = 3 to 5).

(a) The same IC50 values as shown in Table 1.

sPLA2 from bee venom (group III) possesses moderate virucidal activity against HCV, DENV and JEV, whereas sPLA2 from bovine and porcine pancreas (subgroup IB) and bacteria (group XIV) do not exert significant virucidal activity

Next, we tested the possible virucidal activity of sPLA2s from other groups and subgroups. The results showed that sPLA2s obtained from bovine and porcine pancreas (subgroup IB) or from Streptomyces violaceoruber (group XIV) did not neutralise HCV, DENV or JEV even at the 10,000 ng/ml dose (Table 2). However, sPLA2 obtained from the venom of the honeybee Apis mellifera (group III) showed a moderate degree of virucidal activity against HCV, DENV and JEV, with IC50 values of 117, 183 and 49 ng/ml, respectively, while mediating no detectable cytotoxicity or haemolytic activity even at the 10,000 ng/ml dose (Table 2).

The sPLA2 inhibitor manoalide counteracts the antiviral activity of CM-II-sPLA2 against HCV and DENV

Manoalide is known to irreversibly inhibit the enzymatic activity of sPLA2 22,34. We tested the possible inhibitory effect of manoalide on the virucidal activity of CM-II-sPLA2. CM-II-sPLA2 (2 μg/ml) was incubated in the presence or absence of manoalide (10 μg/ml) in a buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2) and 1 mM CaCl2 at 41 °C for 1 h. Then, the manoalide-treated CM-II-sPLA2 or untreated control was tested for virucidal activity against HCV and DENV. The results clearly showed that the virucidal activity of CM-II-sPLA2 against HCV and DENV was markedly inhibited by manoalide (Table 3). This finding suggests that the virucidal activity of CM-II-sPLA2 against HCV and DENV is closely associated with its enzymatic activity.

Table 3.

Inhibition of the virucidal activity of CM-II-sPLA2 by manoalide.

| Virus | IC50 of CM-II-sPLA2 (ng/ml) treated with: | Fold difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manoalide | Control | ||

| HCV | 6.0 ± 4.1 | 0.035 ± 0.005 | 171 |

| DENV | 18.4 ± 13.6 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 71 |

Data are presented as the average ± SEM (n = 2).

Discussion

The PLA2 superfamily is currently classified into six types, namely, sPLA2, Ca2+-dependent cytosolic cPLA2, Ca2+-independent cytosolic iPLA2, platelet-activating factor acetyl hydrolase PAF-AH, lysosomal LPLA2 and adipose-specific AdPLA2 22. More than one-third of the members of the PLA2 superfamily belong to sPLA2, which is further divided into 10 groups (e.g., I, II, III, and XIV) and 18 subgroups (e.g., IA, IB, and IIA). In addition to their highly diverse sequence variations, sPLA2s show functional variations and are involved in a wide range of biological functions and disease occurrence through lipid metabolism and signalling35. Moreover, the sPLA2s enzymes catalyse the hydrolysis at the sn−2 position of the glycerol backbone of phospholipids22.

In the present study, we have demonstrated that CM-II-sPLA2 belonging to subgroup IA22–26 possesses potent virucidal (neutralising) activity against HCV, DENV and JEV particles, which bud through the ER, but does not neutralise the infectivity of SINV, FLUAV, SeV and HSV-1, which bud through the PM or TGN (Table 1). The potent virucidal activity against HCV and DENV was markedly inhibited by a specific sPLA2 inhibitor (Table 3). These results suggest that CM-II-sPLA2 selectively disrupts viral envelope lipid bilayers derived from the ER through phospholipid hydrolysis, although we could not obtain the direct evidence by negative staining electron microscopic analysis of the viral particles.

The phospholipid content of the ER-NE-cis-Golgi membranes differs from that of the trans-Golgi-PM-EE membranes1–3, which basically accounts for the difference in the phospholipid contents of the viral envelope between viruses budding through the ER-NE-cis-Golgi membranes and those budding through the trans-Golgi-PM-EE membranes4–6. For example, viruses budding through the ER (HCV and bovine viral diarrhea virus [BVDV]) were reported to contain more phosphatidylcholine and less phosphatidylserine than viruses budding through the PM (FLUAV, VSV, HIV and Semliki Forest virus [SFV])7. This difference is mainly a reflection of the intrinsic chemical differences between the ER and PM1–3,8,9. Additionally, the biophysical thickness and sturdiness differ between the ER and the PM, with the former being thin and less sturdy with lipid packing defects in the lipid bilayers and the latter being thick and sturdier with tight lipid packaging3,8,9. Moreover, the envelope proteins of viruses belonging to the family Flaviviridae lie flat across the surface of the lipid bilayer of the virion, which allows sPLA2 to access to lipid bilayers more easily than the lipid bilayers of other enveloped viruses with protruding envelope proteins. These physicochemical and structural differences in lipid bilayers and whole envelopes would account for the specificity of the virucidal activity of CM-II-sPLA2 against different viruses. In this sense, CM-II-sPLA2, and possibly other sPLA2s can be used to examine the budding site(s) of infectious particles of various viruses in more detail.

We also need to take into consideration that the phospholipid composition of the viral envelope varies even among different viral species in a given viral family, e.g., HCV, DENV, BVDV and West Nile virus (WNV) of the family Flaviviridae 36. Since the substrate specificity of each sPLA2 should differ depending on its intrinsic properties, the specificity of the virucidal activity of each sPLA2 against a given virus is most likely determined by a particular composition of phospholipids and their distributions on the viral envelope. Moreover, the lipid compositions of HCV, WNV and BVDV, which bud through the ER membrane, were reported to differ from that of a typical ER membrane7,36–38. Thus, viruses probably modify their intracellular microenvironments, including the physicochemical conditions of the host cell membranes to facilitate progeny virus production.

CM-II-sPLA2 has been shown to mediate neurotoxicity in vivo, although to a lesser extent than the CM-III isoform of N. m. mossambica sPLA2 23,25. The CM-III isoform and other neurotoxic sPLA2s possess not only PM-disrupting activity but a high binding affinity for the N-type (neuronal-type) receptor, the latter of which is closely associated with neurotoxicity39. Therefore, CM-II-sPLA2 can conceivably be taken up by neural cells through binding to a receptor (e.g., the N-type receptor) and disrupt certain intracellular membrane compartment(s) inside the neuronal cells to mediate neurotoxicity40,41.

Taking advantage of the intrinsic differences in the physicochemical properties of the membrane lipid bilayers between viruses and host cells as well as the specific interactions between sPLA2s and their receptors, a broad-spectrum antiviral sPLA2(s) can be developed to target viral envelope lipid bilayers derived from the ER without targeting the lipid bilayers of host cell membranes. A CM-II-sPLA2 mutant(s) that has a weaker or no binding affinity for the N-type receptor but retains potent virucidal activity would be a good candidate for development of a novel antiviral drug.

Methods

Chemicals

CM-II-sPLA2 (P7778) and other sPLA2s obtained from A. mellifera honeybee venom (P9279), bovine pancreas (P8913) and S. violaceoruber (P8685) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. sPLA2 from porcine pancreas was a kind gift from Sanyo Fine (Osaka, Japan). Manoalide was purchased from Abcam.

Viruses and cells

HCV (J6/JFH-1 strain)20,21,42,43, DENV (Trinidad 1751 strain)44,45, JEV (Nakayama strain)46, SINV47, FLUAV (A/Udorn/307/72 [H3N2])21, SeV (Fushimi strain)48, VSNJV46, HSV-1 (CHR3 strain)49, EMCV (DK-27 strain)46, CV-B3 (Nancy strain)50, HIV-1 (NLCSFV3 strain)51 and MERS-CoV (EMC2012 strain)52 were described previously. HCV, DENV, JEV, SINV, VSNJV, HSV-1, EMCV and CV-B3 were prepared in Huh7it-1 cells53. FLUAV, HIV-1 and MERS-CoV were prepared in MDCK, HEK293T and Vero cells, respectively. SeV was prepared in embryonated eggs. The infectivity of all viruses except HIV-1 and MERS-CoV was determined on Huh7it-1 cells. Plaque assays were performed for SINV, VSNJV and EMCV by cultivating the virus-inoculated cells for 2 to 4 days under overlay medium containing 1% methylcellulose as described previously46 and the viral titres were expressed as PFU/ml. For the remaining viruses except HIV-1, infectivity was determined by a FA method using specific antibodies against the respective viruses, and viral titres were expressed as CIU/ml as described previously,21,42–45,48. Briefly, viral samples were serially diluted 10-fold in complete medium and inoculated onto Huh7it-1 cells seeded on glass coverslips in a 24-well plate. After virus adsorption for 1 h, the cells were washed with medium to remove residual virus and cultured for 24 h. The virus-infected cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and permeabilised with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. After washing three times with PBS, the cells were incubated with a virus-specific primary antibody for 1 h, followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated respective secondary antibodies for 1 h. Then, the cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope. HIV-1 infectivity was determined by the TZM-bl assay using HIV-1 receptor-expressing HeLa cells, and the viral titres were expressed based on the β-galactosidase activity as reported previously54. MERS-CoV infectivity was determined by a FA method using a specific antibody55 on Vero cells 24 h after infection and also by a TCID50 assay on Vero cells by cultivating the virus-inoculated cells for 4 days, followed by fixing with phosphate-buffered formalin and staining with crystal violet52. The cells were cultivated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% (for cell growth) or 2% (for maintenance culture) foetal bovine serum, non-essential amino acids, penicillin (100 IU/ml) and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Antibodies

The UV-inactivated anti-HCV human serum42,43 and rabbit antisera against FLUAV21, SeV48, HSV-149 and MERS-CoV55 were described previously. A mouse monoclonal antibody against HCV NS3 (Millipore), rabbit polyclonal antibodies against DENV PrM (GeneTex), JEV NS3 (GeneTex) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; Millipore), rabbit antisera against CV-B3 (Denka Seiken) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG (Life Technologies) were purchased.

Virucidal (neutralising) activity test

Cells were seeded into each well of a 6-well plate (plaque assay), 96-well plate (TCID50 test) or on a cover slip in each well of a 24-well plate (FA test). A fixed amount of test virus was mixed with serial dilutions of sPLA2s and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The mixtures were inoculated onto the cells and incubated for another 1 h to allow virus adsorption. Then, the cells were washed with medium to remove the residual virus and cultured for 2 to 4 days (plaque assay and TCID50 test), 24 h (FA test) or 2 days (TZM-bl assay) in fresh medium without sPLA2s. Viral solutions not treated with sPLA2s served as a control. The percent inhibition of viral infectivity by the sPLA2s compared to the untreated control was calculated, and the IC50 was determined.

Time-of-addition test

CM-II-sPLA2 was added to the virus and/or cells at different time points relative to virus inoculation as described below. (i) Pretreatment of the cells with CM-II-sPLA2 before virus inoculation (to examine possible induction of an antiviral status in the cells). Huh7it-1 cells were treated with CM-II-sPLA2 for 1 h. After washing with medium to remove CM-II-sPLA2, the cells were inoculated with virus in the absence of CM-II-sPLA2 for another 1 h. After the residual virus was removed, the cells were cultured for 24 h in the absence of CM-II-sPLA2. (ii) Pretreatment of the virus with CM-II-sPLA2 followed by inoculation of the virus-CM-II-sPLA2 mixture onto the cells (to examine direct virucidal activity). The virus was incubated with CM-II-sPLA2 for 1 h, and the mixtures were inoculated onto Huh7it-1 cells. After 1 h of viral adsorption, the cells were washed with medium to remove the virus and CM-II-sPLA2, and cultured for 24 h in the absence of CM-II-sPLA2. (iii) Post-inoculation (post-entry) treatment of virus-infected cells with CM-II-sPLA2 (to examine post-entry antiviral activity in the infected cells). Huh7it-1 cells were inoculated with virus in the absence of CM-II-sPLA2. After 1 h of viral adsorption, the cells were washed with medium to remove the virus, and cultured for 24 h in the presence of CM-II-sPLA2. The viral titres in the inoculum and the degree of viral protein synthesis and viral RNA replication were determined by infectivity assay, immunoblotting and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses, respectively.

Immunoblotting analysis

Immunoblotting was performed as reported previously21 with slight modifications. Briefly, Huh7it-1 cells were lysed in a Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad) and the cell lysates were separated by 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were probed with the primary antibodies described above, followed by incubation with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Bands were visualised using the Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore) and ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare).

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

The amounts of HCV RNA in the infected cells were determined by qRT-PCR, as described previously53. The amounts of DENV RNA were determined by TaqMan qRT-PCR, according to the protocol reported by Ito et al.56.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity test was performed using the WST-1 reagent (Roche) as reported previously21. Briefly, Huh7it-1 cells plated in each well of a 96-well plate were treated with serial dilutions of sPLA2s at 37 °C for 24 h. Untreated cells served as a control. After this treatment, 10 µl of the WST-1 reagent was added to each well, and the cells were cultured for 4 h. The WST-1 reagent is converted to formazan by mitochondrial dehydrogenases; the amount of formazan was determined by measuring the absorbance of each well using a microplate reader at 450 and 630 nm. The percent cell viability compared to the untreated control was calculated for each dilution of sPLA2s, and the CC50 was determined. The LDH release assay was performed using a commercially available kit (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Haemolytic activity assay

The haemolytic activity was tested using human RBCs as reported previously57,58 with some modifications. Briefly, fresh human RBCs were washed three times with buffer (0.81% NaCl and 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4]) and resuspended in the same buffer. A RBC suspension (107–108 RBCs/ml) was added to another buffer (0.81% NaCl, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], and 2 mM CaCl2) containing various dilutions of sPLA2 (final volume = 100 μl). The mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After centrifugation, haemolysis was determined by measuring the absorbance of the supernatant at 570 nm. Controls for zero haemolysis and 100% haemolysis consisted of RBCs suspended in buffer and 0.5% Triton X-100 in buffer solution (or distilled water), respectively. The percentage of haemolysis was calculated for each dilution of sPLA2s, and the HC50 was determined.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. C. M. Rice (The Rockefeller University, New York, NY, USA) for providing pFL-J6/JFH1. Thanks are also due to Dr. K. Hayashi for providing HSV-1 and rabbit anti-HSV-1 antiserum. This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid for Research on Viral Hepatitis from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED). This work was also supported in part by a grant-in-aid for Special Research on Dengue Vaccine Development from Tokyo Metropolitan Government.

Author Contributions

H.H. conceived the experiments, analysed the results and wrote the main manuscript text, M.C. conducted most of the experiments and analysed the results, C.A.-U., M.K. and L.D. conducted part of HCV and DENV experiments, Y.T. and W.K. conducted MERS-CoV experiments, K.S. and Y.K. conducted HIV experiments, M.H., K.S. and T.N. conducted electron microscopy analysis, and M.K. conducted part of HCV and DENV experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-16130-w.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.van Meer G, Voelker DR, Feigenson GW. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;9:112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bigay J, Antonny B. Curvature, lipid packing, and electrostatics of membrane organelles: defining cellular territories in determining specificity. Dev. Cell. 2012;23:886–895. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson CL, Walch L, Verbavatz J-M. Lipids and their trafficking: an integral part of cellular organization. Dev. Cell. 2016;39:139–153. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison, S. C. Principle of Virus Structures in Fields Virology, 6th ed. Vol. 1 (ed. Knipe, D. M. & Howley, P. M.) 52–86 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013).

- 5.Reddy T, Sansom MS. The role of the membrane in the structure and biophysical robustness of the dengue virion envelope. Structure. 2016;24:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy T, Sansom MS. Computational virology: from the inside out. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1858:1610–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callens N, et al. Morphology and molecular composition of purified bovine viral diarrhea virus envelope. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005476. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Meer G, de Kroon AI. Lipid map of the mammalian cell. J. Cell. Sci. 2011;124:5–8. doi: 10.1242/jcs.071233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monje-Galvan V, Klauda JB. Modeling yeast organelle membranes and how lipid diversity influences bilayer properties. Biochemistry. 2015;54:6852–6861. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vacklin HP, Tiberg F, Fragneto G, Thomas RK. Phospholipase A2 hydrolysis of supported phospholipid bilayers: a neutron reflectivity and ellipsometry study. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2811–2821. doi: 10.1021/bi047727a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindenbach, B. D., Murray, C. L., Thiel, H.-J. & Rice, C. M. Flaviviridae in Fields Virology, 6th ed. Vol. 1 (ed. Knipe, D. M. & Howley, P. M.) 712–746 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013).

- 12.Welsch S, et al. Composition and three-dimensional architecture of the dengue virus replication and assembly sites. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheel TK, Rice CM. Understanding the hepatitis C virus life cycle paves the way for highly effective therapies. Nat. Med. 2013;19:837–849. doi: 10.1038/nm.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw, M. L. & Palese, P. Orthomyxoviridae in Fields Virology, 6th ed. Vol. 1 (ed. Knipe, D. M. & Howley, P. M.) 1151–1185 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013).

- 15.Muller VD, et al. Crotoxin and phospholipases A2 from Crotalus durissus terrificus showed antiviral activity against dengue and yellow fever viruses. Toxicon. 2012;59:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muller VD, et al. Phospholipase A2 isolated from the venom of Crotalus durissus terrificus inactivates dengue virus and other enveloped viruses by disrupting the viral envelope. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J-O, et al. Lysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by a specific secreted human phospholipase A2. J. Virol. 2007;81:1444–1450. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01790-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goff, S. P. Retroviridae in Fields Virology, 6th ed. Vol. 2 (ed. Knipe, D. M. & Howley, P. M.) 1424–1473 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013).

- 19.Fenard D, et al. Secreted phospholipases A2, a new class of HIV inhibitors that block virus entry into host cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:611–618. doi: 10.1172/JCI6915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ratnoglik SL, et al. Antiviral activity of extracts from Morinda citrifolia leaves and chlorophyll catabolites, pheophorbide a and pyropheophorbide a, against hepatitis C virus. Microbiol Immunol. 2014;58:188–194. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Bitar AM, et al. Virocidal activity of Egyptian scorpion venoms against hepatitis C virus. Virol. J. 2015;12:47. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0276-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dennis EA, Cao J, Hsu Y-H, Magrioti V, Kokotos G. Phospholipase A2 enzymes: physical structure, biological function, disease implication, chemical inhibition, and therapeutic intervention. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:6130–6185. doi: 10.1021/cr200085w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joubert FJ. Naja mossambica mossambica venom. Purification, some properties and the amino acid sequences of three phospholipases A (CM-I, CM-II and CM-III) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1977;493:216–227. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(77)90275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmad T, Lawrence AJ. Purification and activation of phospholipase A2 isoforms from Naja mossambica mossambica (spitting cobra) venom. Toxicon. 1993;31:1279–1291. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(93)90401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin W-W, Chang P-L, Lee C-Y, Joubert FJ. Pharmacological study on phospholipases A2 isolated from Naja mossambica mossambica venom. Proc. Natl. Sci. Counc. Repub. China B. 1987;11:155–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kini RM, Evans HJ. Structure-function relationships of phospholipases. The anticoagulant region of phospholipases A2. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:14402–14407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuhn, R. J. Togaviridae in Fields Virology, 6th ed. Vol. 1 (ed. Knipe, D. M. & Howley, P. M.) 747–794 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013).

- 28.Lamb, R. A. & Parks, G. D. Paramyxoviridae in Fields Virology, 6th ed. Vol. 1 (ed. Knipe, D. M. & Howley, P. M.) 957–995 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013).

- 29.Pellett, P. E. & Roizman, B. Herpesviridae in Fields Virology, 6th ed. Vol. 2 (ed. Knipe, D. M. & Howley, P. M.) 1802–1822 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013).

- 30.Lyles, D. S., Kuzmin, I. V & Rupprecht, C. E. Rhabdoviridae in Fields Virology, 6th ed. Vol. 1 (ed. Knipe, D. M. & Howley, P. M.) 885–922 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013).

- 31.Masters, P. S. & Perlman, S. Coronaviridae in Fields Virology, 6th ed. Vol. 1 (ed. Knipe, D. M. & Howley, P. M.) 825–858 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013).

- 32.Orenstein JM, Banach B, Baker SC. Morphogenesis of coronavirus HCoV-NL63 in cell culture: a transmission electron microscopic study. Open. Infect. Dis. J. 2008;2:52–58. doi: 10.2174/1874279300802010052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Racaniello, V. R. Picornaviridae in Fields Virology, 6th ed. Vol. 1 (ed. Knipe, D. M. & Howley, P. M.) 453–489 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013).

- 34.Lombardo D, Dennis EA. Cobra venom phospholipase A2 inhibition by manoalide. A novel type of phospholipase inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:7234–7240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murakami M, Sato H, Miki Y, Yamamoto K, Taketomi Y. A new era of secreted phospholipase A2. J. Lipid Res. 2015;56:1248–1261. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R058123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martín-Acebes MA, Vázquez-Calvo Á, Saiz J-C. Lipids and flaviviruses, present and future perspectives for the control of dengue, Zika, and West Nile viruses. Prog. Lipid Res. 2016;64:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merz A, et al. Biochemical and morphological properties of hepatitis C virus particles and determination of their lipidome. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:3018–3032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martín-Acebes MA, et al. The composition of West Nile virus lipid envelope unveils a role of sphingolipid metabolism in flavivirus biogenesis. J. Virol. 2014;88:12041–12054. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02061-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lambeau G, Lazdunski M. Receptors for a growing family of secreted phospholipases A2. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:162–170. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(99)01300-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montecucco C, Rossetto O. How do presynaptic PLA2 neurotoxins block nerve terminals? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:266–270. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01556-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Šribar J, Oberčkal J, Križaj I. Understanding the molecular mechanism underlying the presynaptic toxicity of secreted phospholipases A2: An update. Toxicon. 2014;89:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bungyoku Y, et al. Efficient production of infectious hepatitis C virus with adaptive mutations in cultured hepatoma cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2009;90:1681–1691. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.010983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deng L, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection promotes hepatic gluconeogenesis through an NS5A-mediated, FoxO1-dependent pathway. J. Virol. 2011;85:8556–8568. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00146-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hotta H, et al. Enhancement of dengue virus type 2 replication in mouse macrophage cultures by bacterial cell walls, peptidoglycans, and a polymer of peptidoglycan subunits. Infect. Immun. 1983;41:462–469. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.2.462-469.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hotta H, Wiharta AS, Hotta S. Antibody-mediated enhancement of dengue virus infection in mouse macrophage cell lines, Mk1 and Mm1. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1984;175:320–327. doi: 10.3181/00379727-175-41802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song J, Fujii M, Wang F, Itoh M, Hotta H. The NS5A protein of hepatitis C virus partially inhibits the antiviral activity of interferon. J. Gen. Virol. 1999;80:879–886. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-4-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsumura T, Stollar V, Schlesinger RW. Effects of ionic strength on the release of dengue virus from Vero cells. J. Gen. Virol. 1972;17:343–347. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-17-3-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hayashi T, Hotta H, Itoh M, Homma M. Protection of mice by a protease inhibitor, aprotinin, against lethal Sendai virus pneumonia. J. Gen. Virol. 1991;72:979–982. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-4-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayashi K, Iwasaki Y, Yanagi K. Herpes simplex virus type 1-induced hydrocephalus in mice. J. Virol. 1986;57:942–951. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.3.942-951.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mikami S, et al. Low-dose N omega-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester treatment improves survival rate and decreases myocardial injury in a murine model of viral myocarditis induced by coxsackievirus B3. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;220:983–989. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suzuki Y, et al. Determinant in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 for efficient replication under cytokine-induced CD4(+) T-helper 1 (Th1)- and Th2-type conditions. J. Virol. 1999;73:316–324. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.316-324.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Terada Y, Kawachi K, Matsuura Y, Kamitani W. MERS coronavirus nsp1 participates in an efficient propagation through a specific interaction with viral RNA. Virology. 2017;511:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2017.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Apriyanto DR, et al. Anti-hepatitis C virus activity of a crude extract from longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.) leaves. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2016;69:213–220. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2015.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wei X, et al. Emergence of resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients receiving fusion inhibitor (T-20) monotherapy. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2002;46:1896–1905. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1896-1905.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fukuma A, et al. Inability of rat DPP4 to allow MERS-CoV infection revealed by using a VSV pseudotype bearing truncated MERS-CoV spike protein. Arch. Virol. 2015;160:2293–2300. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2506-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ito M, et al. Development and evaluation of fluorogenic TaqMan reverse transcriptase PCR assays for detection of dengue virus types 1 to 4. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:5935–5937. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5935-5937.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moerman L, et al. Antibacterial and antifungal properties of alpha-helical, cationic peptides in the venom of scorpions from southern Africa. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:4799–4810. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Diego-García E, et al. Cytolytic and K+ channel blocking activities of β-KTx and scorpine-like peptides purified from scorpion venoms. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:187–200. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7370-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.