Abstract

The terms ‘licensed’, ‘unlicensed’, and ‘off‐label’, often used in relation to marketing and prescribing medicinal products, may confuse UK prescribers. To market a medicinal product in the UK requires a Marketing Authorization (‘product licence’) for specified indications under specified conditions, regulated by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). The Marketing Authorization includes the product's agreed terms of use (the ‘label’), described in the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). Prescribing a licensed product outside those terms is called ‘off‐label’ prescribing. Products for which no‐one holds a UK Marketing Authorization are unlicensed. Prescribers can prescribe authorized products according to the conditions described in the SmPC (‘on‐label’) or outside those conditions (‘off‐label’). They can also prescribe unauthorized products, even if they are unlicensed in the UK, if they are licensed elsewhere or if they have been manufactured in the UK by a licensed manufacturer as a ‘special’. The complexities of this system can be understood by considering the status of the manufacturer of the product, the company that markets it (which may or may not be the same), the product itself, and its modes of use, and by emphasizing the word ‘authorized’. If a Marketing Authorization is granted to the supplier of a product, it will specify the authorized modes of use; the product will be prescribable as authorized (i.e. ‘on‐label’) or in other modes of use, which will all be off‐label. Unlicensed products with no authorized modes of use can be regarded as ‘unauthorized products’. All ‘specials’ can be regarded as authorized products lacking authorized modes of use.

Keywords: authorized medicines, licensed medicines, market authorization, off‐label prescribing, unlicensed prescribing

Introduction

The terms ‘unlicensed’ and ‘off‐label’ in relation to the marketing and prescribing of medicinal products are widely used but are potentially confusing and may be misunderstood. Here we discuss definitions and offer clarifications. We shall deal only with legislation in the UK.

We exclude from this discussion medical devices and advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs, products used for gene therapy or somatic cell therapy or tissue engineered products) 1, for which there are special exemptions.

Regulation of medicines in the UK

The history of medicines regulation in the UK 2 is briefly described in Appendix 1.

In the UK there is a Licensing Authority responsible for granting, renewing, varying, suspending, and revoking licences for medicinal products. This Authority, created by the 1968 Medicines Act, is defined as ‘the Minister of Health [in England & Wales], the Secretary of State concerned with health in Scotland and the Minister of Health and Social Services for Northern Ireland.’ Currently, the Licensing Authority is advised by the Commission on Human Medicines (CHM) through the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), which issues all authorizations for medicinal products for human use and licences for manufacturers and wholesalers of such products across the UK.

Medicines regulation controls the ways in which medicinal products are marketed, not the ways in which they are prescribed. Prescribers are regulated by other bodies, for example the General Medical Council (GMC) for doctors, the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) for pharmacists, and the Nursing & Midwifery Council (NMC) for nurses and midwives.

The 1968 Medicines Act introduced the UK system whereby applicants are granted licences (now known as Marketing Authorizations, colloquially known as product licences), permitting them to market medicinal products for specified indications under specified conditions. The current UK law is contained in the Human Medicines Regulations 2012, a UK Statutory Instrument, which is legislation secondary to the Medicines Act and not itself a full Act 3. The regulation of medicinal products for human use in the UK is also currently subject to EU law, as outlined in Directive 2001/83/EC on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use 4, which is discussed in relevant parts of the text below and also in Appendices 3 and 4. The MHRA is only one regulatory agency that contributes to the deliberations of the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and in some cases it has no major input. Even when a national licence is granted in the UK, regulation is still subject to EU law. At the time of writing it is not clear how the MHRA will make regulatory recommendations if and when the UK leaves the European Union. In the first instance, all EU law will be incorporated into UK statutes, but changes may subsequently be made. It is unlikely that UK regulation will revert to the position that existed before the formation of the EMA (see Appendix 1), but neither is it clear to what extent the MHRA will be willing to accept EMA decisions into which it has had no input, rather than setting up the complex apparatus, under amended legislation, whereby it could make its own recommendations to the Licensing Authority. Any changes that are made may take many years to effect.

Definitions

Here we explain a range of terms that are pertinent to the use of unlicensed medicines and the off‐label use of licensed medicines. The relevant definitions are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions discussed in this paper

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Medicinal product | (a) any substance or combination of substances presented as having properties of preventing or treating disease in human beings; or |

| (b) any substance or combination of substances that may be used by or administered to human beings with a view to | |

| (i) restoring, correcting, or modifying a physiological function by exerting a pharmacological, immunological, or metabolic action, or | |

| (ii) making a medical diagnosis | |

| Marketing authorization | Permission granted to a Marketing Authorization Holder legally to sell, supply, or export, procure the sale, supply or exportation, or procure the manufacture or assembly for sale, supply or exportation of a specified medicinal product |

| Authorized medicinal product (‘licensed product’) | A medicinal product, marketed by a specified company, for which there is in force |

| (a) a marketing authorization; | |

| (b) a certificate of registration as a homeopathic medicinal product; | |

| (c) a traditional herbal registration; or | |

| (d) an Article 126a authorization (see below) | |

| Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) | That part of the Marketing Authorization that contains essential information for the use of a medicine, including pharmacological properties, authorized indications, qualitative and quantitative information on benefits and harms, information for individualized care, and pharmaceutical information |

| Article 126a authorization | An EU authorization that can be issued to license a product whose use is justified for public health reasons and that has been imported from another Member State in the European Union |

| Authorized modes of use | The ways of using the medicinal product as specified in the Summary of Product Characteristics (see Appendix 2) |

| Unauthorized product (‘unlicensed product’) | A medicinal product for human use in respect of which no marketing authorization has been granted by a relevant licensing authority |

| Label | A notice describing or otherwise relating to the contents of a medicinal product; the agreed terms of the Marketing Authorization granted in respect of a medicinal product and set out in the Summary of Product Characteristics |

| Off‐label prescribing | Prescribing of an authorized product for use in a way that is not described in the Summary of Product Characteristics |

Note on nomenclature

A Marketing Authorization is defined below and in Table 1. Those who hold Marketing Authorizations in the UK are known as Marketing Authorization Holders (MAHs). Separate licences are issued to manufacturers and wholesalers. A Marketing Authorization Holder may also hold a separate manufacturing licence.

Because a Marketing Authorization is granted to the MAH, not to the product, terms such as ‘licensed drug’, ‘licensed medicine’, and ‘licensed product’, commonly used colloquially, are not strictly accurate. Neither the drug itself nor the medicinal product in which it is formulated is licensed. It is the MAH who is licensed, i.e. given permission by the Licensing Authority to market the product. Nevertheless, we shall use the terms ‘licensed product’ and ‘unlicensed product’ here, as they are commonly used and afford appropriate shorthand. Thus, when we say ‘licensed product’ we mean a product whose MAH has been granted a licence to market it for specified indications, and when we say ‘unlicensed product’ we refer to a product for which no UK licence has been issued for any indication.

Marketing authorization and licensed and unlicensed medicinal products

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined a marketing authorization as ‘an official document issued by the competent drug regulatory authority for the purpose of marketing or free distribution of a product after evaluation for safety, efficacy and quality’ 5. Although UK legislation has not explicitly defined the terms ‘product licence’ or ‘marketing authorization’, Section 7 of the 1968 Medicines Act stipulates that, except in accordance with a product licence, ‘no person shall, in the course of a business carried on by him …

sell, supply or export any medicinal product, or

procure the sale, supply or exportation of any medicinal product, or

procure the manufacture or assembly of any medicinal product for sale, supply or exportation.’

This text implies that a marketing authorization (product licence) can be defined as ‘permission granted to a marketing authorization holder to sell, supply, or export, procure the sale, supply or exportation, or procure the manufacture or assembly for sale, supply or exportation of a specified medicinal product’.

There are two main routes for authorizing medicines in the EU, a centralized route and a national route 6. For centralized authorization, a single application is submitted to the EMA. The licence, if granted, allows the MAH to market the medicine and make it available in all Member States and in the European Economic Area (EEA) countries (Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway). In addition, each EU Member State has its own national authorization procedures, under which most medicines in the UK have been authorized, either because they were authorized before the EMA was established or because they did not come within the scope of the centralized procedure. However, an MAH who holds a licence, whether via the centralized or national route, is not obliged to market the product in a country in which the product is licensed. If a product is licensed but not marketed it may, if prescribed, be imported from a country in which it is marketed.

An ‘unlicensed product’ can be defined, based on the definition in the Unlicensed Medicinal Products for Human Use (Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies) (Safety) Regulations 2003 7, as ‘a medicinal product for human use [with some exceptions, such as herbal products], in respect of which no marketing authorization has been granted by the [national] licensing authority or by the European Medicines Agency’.

A medicinal product is defined as:

-

‘(a)

any substance or combination of substances presented as having properties of preventing or treating disease in human beings; or

-

(b)any substance or combination of substances that may be used by or administered to human beings with a view to

-

(i)restoring, correcting or modifying a physiological function by exerting a pharmacological, immunological or metabolic action, or

-

(ii)making a medical diagnosis.’

-

(i)

A medicinal product is authorized if there is in force for the product:

a marketing authorization;

a certificate of registration as a homoeopathic medicinal product 8;

a traditional herbal registration; or

an Article 126a authorization.

An Article 126a authorization, under EU law, is one that can be issued to license a product whose use is justified for public health reasons and that has been imported from another Member State in the European Union where it has been authorized. For example, over 1600 products have been licensed in Malta using this method 9. At the time of writing it is not clear what will happen to this part of the definition if and when the UK leaves the EU.

Any medicinal product for which a UK marketing authorization has not been granted is an unlicensed product in the UK, even if it is licensed elsewhere. This is made explicit in Section 7 of the 1968 Act, which stipulates that ‘[n]o person shall import any medicinal product except in accordance with a product licence’. Importation from non‐EU states is covered in the 2012 Human Medicines Regulations.

Pharmaceutical modification of a licensed product can result in an unlicensed product. For example, bevacizumab is licensed for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. If an undiluted solution of bevacizumab were used for intravitreous injection to treat age‐related macular degeneration, that would be using it off‐label (see below). If, on the other hand, a solution was, say, diluted before use or divided into several aliquots, the secondary formulations would be regarded as being unlicensed 10, 11, 12. How much pharmaceutical modification results in an unlicensed product is unclear.

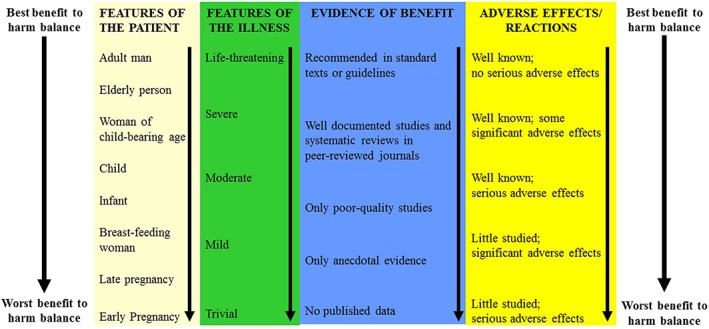

The licensing system in the UK is intended to protect patients from the use of medicines with a poor benefit‐to‐harm balance, based on quality, efficacy, and safety. However, when a medicine has been licensed, it is prescribers who assess the benefit‐to‐harm balance and make decisions about whether that medicine should be prescribed, guided by factors such as those shown in Figure 1, which deal with the patient, the illness, the benefits, and the harms. The benefit‐to‐harm balance is most favourable when (a) the patient has little susceptibility to the potential harms, (b) the disease is serious and severe, (c) there is substantial and well‐established efficacy, and (d) harms are well defined, unlikely, and trivial. This is especially important when the prescriber strays from the authorized modes of use.

Figure 1.

Four factors that influence the benefit to harm balance of drug therapy: features of the patient, features of the illness, the evidence of benefit, and adverse effects or reactions

Label and labelling

The term ‘label’, now widely used, originated in US legislation in 1938, when the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act defined a label as ‘a display of written, printed, or graphic matter upon the immediate container of any article; and a requirement … that any word, statement, or other information appear[ing] on the label shall not be considered to be complied with unless such word, statement, or other information also appears on the outside container or wrapper, if any there be, of the retail package of such article, or is easily legible through the outside container or wrapper.’

‘Labelling’ was defined in the 1938 Act as ‘all labels and other written, printed, or graphic matter (1) upon any article or any of its containers or wrappers, or (2) accompanying such article.’ Similarly, a drug label is described in The Human Medicines Regulations 2012 as ‘a notice describing or otherwise relating to the contents’.

The term ‘label’ is now used to mean not merely the ‘written, printed, or graphic matter’ that accompanies the formulation, but also the informative content of such matter, which in the UK is contained in the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC), previously called the Product Data Sheet. The SmPC is a legal document, approved as part of the marketing authorization of each medicine, whose contents, as currently prescribed by EU law 13, are listed in Appendix 2.

SmPCs can vary markedly in describing the same medicine formulated by different manufacturers. As an example, each of six formulations of bendroflumethiazide, described in five SmPCs currently listed in the Electronic Medicines Compendium 14, constitutes a separate medicinal product, each with its own product licence number. The SmPCs for these different formulations differ in ways that are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

An example of differences in UK SmPCs of products containing the same active ingredient, bendroflumethiazide, marketed in the same strengths by different manufacturers

| Marketing Authorization Holder | Sovereign Medical (brand name Aprinox; one SmPC for two products) | Wockhardt (two SmPCs, one for each strength) | Actavis (two SmPCs, one for each strength) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strengths | 2.5 and 5 mg | 2.5 and 5 mg | 2.5 and 5 mg |

| Stated indications |

• Oedema [conditions not specified] • Hypertension • Suppression of lactation |

• Essential hypertension • Oedema [conditions specified] |

• Reduction of fluid retention by diuresis; oedema [conditions specified] • Antihypertensive agent |

| Stated contraindications |

• Known hypersensitivity to thiazides • Refractory hypokalaemia, hyponatraemia, hypercalcaemia • Severe renal and hepatic impairment • Symptomatic hyperuricaemia • Addison's disease |

• Hypercalcaemia • Severe renal insufficiency or anuria • Severe hepatic impairment (risk of precipitation of encephalopathy) • Addison's disease • [Administration] with lithium carbonate |

• Hypersensitivity to thiazides and any other ingredient • Patients with rare hereditary problems of galactose intolerance, the Lapp lactase deficiency or glucose‐galactose malabsorptiona • Severe renal or hepatic insufficiency • Hypercalcaemia; refractory hypokalaemia; hyponatraemia; symptomatic hyperuricaemia • Addison's disease |

| Advice on monitoring therapy |

• Renal function should be continuously [sic] monitored • Regular ongoing monitoring and blood tests are to be performed in elderly patients and patients who are on long‐term treatment with bendroflumethiazide |

• Elderly: electrolyte balance and renal function should be carefully monitored • Serum electrolyte and blood urea levels should be carefully monitored in seriously ill patients • Blood glucose concentrations should be monitored in patients taking antidiabetics |

• Renal function should be monitored • Elderly patients and those on long‐term treatment need regular blood tests to monitor electrolyte levels • Serum calcium levels should be monitored to ensure that they do not become excessive • Patients [taking digoxin] should be monitored for signs of digoxin intoxication, especially arrhythmias • Plasma lithium concentrations must be monitored when these drugs are given concurrently • Patients [taking carbenoxolone and bendroflumethiazide] should be monitored and given potassium supplements when required |

All three products contain lactose as an excipient

Off‐label prescribing

To recap: the Marketing Authorization (product licence) of an approved medicinal product is granted to the Market Authorization Holder. The product is then colloquially referred to as a ‘licensed product’. The product's ‘approved uses’ are the modes of use listed in Section 4 (‘Clinical Particulars’) of the SmPC (‘the label’), which accompanies the licence.

If a licensed product is prescribed for use in a way that differs from the authorized ways described in the label, it is said to be prescribed ‘off‐label’. In other words, off‐label prescribing is the prescribing of a licensed product for use in an unauthorized way, which is any way that differs from the ways specified in the SmPC. This is not the same as prescribing an unlicensed product. Table 3 lists different types of off‐label and unlicensed prescribing; some are less hazardous than others, and the degree of hazard varies in different circumstances.

Table 3.

Types of off‐label and unlicensed prescribing

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Types of off‐label prescribing in which the medicine is not approved for the intended indication | |

| 1. The branded formulation is not approved for the intended indication, but other branded formulations of the same medicine are so approved | Inderal–propranolol is not approved for treatment of infantile haemangiomas, but Hemangiol–propranolol is so approved |

| 2. The medicine is not approved in any formulation for the intended indication, but other medicines of the same pharmacological class, which might be expected to be efficacious, are so approved | Licensed formulations of bisoprolol and celiprolol do not include the treatment of migraine among their approved indications, but licensed formulations of propranolol and oxprenolol do |

| 3. The medicine is not approved in any formulation for the intended indication, and no other medicine of the same pharmacological class is so approved either | Streptomycin is used to treat infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, but is not licensed for that indication in the UK; neither are other aminoglycoside antibiotics listed in the British National Formulary specifically licensed for the treatment of infection with M. tuberculosis |

| 4. The medicine is approved for an indication and can be used in cases where the indication is assumed but not known | Use of ampicillin, indicated for the treatment of a wide range of bacterial infections caused by ampicillin‐sensitive organisms, to treat infections whose cause is not known or when infecting bacteria are not known to be sensitive |

| Types of off‐label prescribing in which the medicine is approved for the intended indication but not in other respects, e.g. population, dose, or frequency of administration | |

| 5. For an unapproved age group | Many examples of prescribing for children, when the prescribed drug is approved for the relevant indication in adults but not children |

| 6. In an unapproved dosage regimen | Use of an oral contraceptive in twice the recommended dose to obviate reduced efficacy due to a drug–drug interaction |

| 7. By an unapproved route of administration | Giving bevacizumab intravitreously for age‐related macular degeneration (AMD); this is also an example of an off‐label indication, since the approved indications for bevacizumab do not include AMD |

| 8. With omission of therapy with a drug mandated in the SmPC for co‐administration | Prescribing infliximab without methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis as a therapeutic trial in a patient who cannot tolerate methotrexate |

| 9. When monitoring that is mandated by the SmPC is omitted | Failing to monitor serum sodium concentrations in patients taking low‐dose diuretics for hypertension, taking into account evidence that it is of no therapeutic benefit to do so |

| Unlicensed products that can be prescribed but need to be imported or provided as specials | |

| Glycopyrronium bromide (available in the UK for injection) | Glycopyrronium bromide 0.05% topical solution |

| Hydroquinone (no licensed product marketed in the UK) | Hydroquinone 4% cream |

| Melatonin (available in the UK as a modified‐release formulation) | Melatonin oral solutions and oral suspensions 2–10 mg per 5 ml |

The licensing restrictions stipulated in the 1968 Medicines Act and the 2012 Regulations relate to marketing and specify sale, supply, export, and import. They do not relate to prescribing. For example, a registered medical practitioner with a licence to practise granted by the GMC has a right to prescribe.

Regulatory guidance

The two main UK regulatory bodies that issue guidance about the prescribing of medicinal products are the GMC and the MHRA.

The GMC issued guidance in 2006 15, revised in 2008 16, in which it listed the precautions that prescribers should taken when writing prescriptions for all medicines, and specifically listing the different precautions required when prescribing unlicensed medicines and, separately, licensed medicines off‐label.

However, in 2013 17 the GMC, in its document ‘Good practice in prescribing and managing medicines and devices (2013)’, revised its guidance, conflating in Paragragh 67 the two categories of unlicensed medicines and licensed medicines that are used outside the terms of their UK licence (i.e. used off‐label), applying the term ‘unlicensed medicines’ to cover both, thus: ‘The term “unlicensed medicine” is used to describe medicines that are used outside the terms of their UK licence or which have no licence for use in the UK.’

The GMC supported this change from its previous guidance by citing the MHRA publication The supply of unlicensed medicinal products (‘specials’), MHRA Guidance Note 14. However, the MHRA's Guidance makes it clear that the term ‘unlicensed medicine’ specifically describes medicines that have no UK licence. When a medicine is ‘used outside the terms of [the] UK licence’ that has been granted to its manufacturer, such use is off‐label, not unlicensed, as the earlier GMC guidance made clear. Subsequent paragraphs in this section of the GMC's 2013 document (paragraphs 68–70) use the term ‘unlicensed’ apparently to mean either ‘off‐label’ or ‘unlicensed and/or off‐label’ (see also below). Given this, it is hard to interpret this section of the GMC's document.

We also note that in November 2015 the GMC offered a further elaboration 18:

‘For clarity, in GMC guidance the term ‘unlicensed medicines’ refers to both medicines with no UK licence, and those being used outside of the terms of their licence (commonly referred to as ‘off‐label’). Although there are of course differences between medicines which do not hold any UK licence and those used outside of the terms of their licence – our guidance is the same for both circumstances which is why they are grouped together in this context.’

Perhaps surprisingly, the GMC also implies that the duties of prescribers are the same when they prescribe licensed medicines, whether within or outside the terms of their licence, or unlicensed medicines, stating that ‘Importantly, prescribing unlicensed medicines will not put your registration at risk any more than other areas of practice covered by our guidance’.

We find nothing in the MHRA's Guidance Note 14 to support the GMC's use of the term ‘unlicensed’ to encompass licensed medicines prescribed outside the terms of the licence (i.e. off‐label). Indeed, the MHRA's note clearly differentiates between ‘unlicensed’ and ‘off‐label’ and sets out their different uses in both Section 2.4 and at greater length in Section 2 of Appendix 2 in the document 19, which reads:

-

‘1

An unlicensed product should not be used where a product available and licensed within the UK could be used to meet the patient's special need.

-

‘2

Although MHRA does not recommend “off label” (outside of the licensed indications) use of products, if the UK licensed product can meet the clinical need, even “off‐label”, it should be used instead of an unlicensed product. Licensed products available in the UK have been assessed for quality safety and efficacy. If used “off‐label” some of this assessment may not apply, but much will still be valid. This is better than the use of an un‐assessed, unlicensed product. The fact that the intended use is outside of the licensed indications is therefore not a reason to use an unlicensed product. It should be understood that the prescriber's responsibility and potential liability are increased when prescribing off‐label.

-

‘3

If the UK product cannot meet the special need, then another (imported) medicinal product should be considered, which is licensed in the country of origin.

-

‘4

If none of these options will suffice, then a completely unlicensed product may have to be used, for example, UK manufactured “specials”, which are made in GMP [Good Manufacturing Practice] inspected facilities, but which are otherwise un‐assessed (GMP inspection of “specials” manufacturers is not product specific). There may also be other products available which are unlicensed in the country of origin.

-

‘5

The least acceptable products are those that are unlicensed in the country of origin, and which are not classed as medicines in the country of origin (but are in the UK). For example, the use of products from countries where they are classed as supplements, not pharmaceuticals, and may not be made to expected standards of pharmaceutical GMP. These should be avoided whenever possible.’

The text of this appendix clearly distinguishes the use of unlicensed products from the off‐label use of licensed products outside their licensed (i.e. approved) indications as stated in the label.

In contrast, the GMC's 2013 guidance dichotomizes products as licensed and unlicensed, and does not mention off‐label use:

‘68. You should usually prescribe licensed medicines in accordance with the terms of their licence. However, you may prescribe unlicensed medicines where, on the basis of an assessment of the individual patient, you conclude, for medical reasons, that it is necessary to do so to meet the specific needs of the patient.

-

‘69. Prescribing unlicensed medicines may be necessary where:

There is no suitably licensed medicine that will meet the patient's need....

Or where a suitably licensed medicine that would meet the patient's need is not available.’

The Chairman of the GMC stated in April 2015 20 that the GMC's guidance ‘is based on current European law. The key judgment was European Commission v. Republic of Poland (C‐185/10) in 2012. This made clear that it was unlawful to prescribe an unlicensed medicine (medicines which have no licence for use in the UK or are used outside the terms of their licence) on grounds of cost when there was a licensed product available.’ However, we believe that this reference to the cited case confuses marketing and prescribing, as Evans has suggested 21.

The text of the Judgment of the Court (Third Chamber) in the case of the European Commission vs. the Republic of Poland [22; Appendix 3] made it clear that the case dealt, not with prescribing, but with authorization to market a medicinal product. It was specifically about the importation of a medicinal product that had ‘the same active substances, the same dosage and the same form’ as other licensed products, but was cheaper, without the need for national authorization, where Article 4 of the [Polish] Law on Medicinal Products conflicted with Article 6(1) of Directive 2001/83/EC.

Providing medicines for ‘special needs’

It is not illegal in the UK for a registered prescriber to prescribe an unlicensed product or a licensed product off‐label. Unlicensed medicines can be supplied by so‐called ‘special order’ manufacturers, paradoxically under licence from the MHRA, obviating the need for a marketing authorization. The relevant details about such ‘specials’ are given in Appendix 4.

Although the prescription of an unlicensed product is restricted to specified circumstances, the restrictions do not apply to off‐label prescription. This is why it is important that the definitions of ‘unlicensed’ and ‘off‐label’ should be clear and properly understood.

An operational description

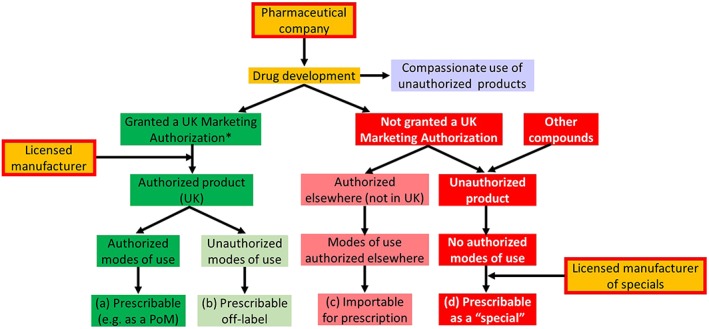

We believe that the confusion that can arise from the use of the terms ‘licensed’, ‘unlicensed’, and ‘off‐label’ can be mitigated by recognizing that there are several components of the processes of authorization, manufacture, marketing, and prescribing of medicinal products, as shown in Figure 2. The key word is ‘authorized’.

Figure 2.

How authorized and unauthorized products are used and prescribed; the categories (a)–(d) correspond to those in Appendix 4;

*the MAH and the licensed manufacturer may or may not be the same company and may or may not be the company that develops the drug;

PoM = prescription‐only medicine

When a product has been developed, a Marketing Authorization may or may not be issued to a relevant applicant. A Marketing Authorization Holder (MAH) holds an authorization to market an authorized medicinal product, the term that is used in the 2012 Human Medicines Regulations to describe products for which authorizations have been issued. The modes of use of authorized medicinal products, as described in the SmPC, include the indications, contraindications, dosages, routes of administration, and requirements for monitoring. They are similarly authorized by agreement between the MHRA and the MAH. We use the term ‘modes of use’ rather than ‘uses’, as the latter could be misinterpreted as being restricted to indications. Manufacturers, who are often the MAHs, are also authorized. Thus:

Authorized medicinal products with authorized modes of use are prescribable (dark green boxes in Figure 2).

If any mode of use is not part of the marketing authorization, an authorized medicinal product may nevertheless also be prescribed, but in that case its use will be off‐label (light green boxes in Figure 2).

Products that are unlicensed in the UK, ‘unauthorized medicinal products’, have by definition no authorized modes of use; such products can be imported and prescribed if they have been authorized elsewhere (rose‐coloured boxes in Figure 2).

Otherwise unauthorized products are prescribable as ‘specials’ under the current regulations, if manufactured by a licensed ‘specials’ manufacturer (red boxes in Figure 2).

Compassionate use (lavender box) allows the use of unauthorized medicinal products, under strict conditions, so that products in development can be given to patients who have a disease with no satisfactory authorized therapies and who cannot enter clinical trials 23.

The MHRA has set out a preferred order for prescribing products of different status (see items a–d in Appendix 4 and the bottom line in Figure 2).

Conclusion

Medicines legislation is designed to ensure that only products that have been assessed by a regulatory agency, and are of acceptable quality of manufacture, efficacy in the proposed indications, and safety, can be sold, supplied, or exported. It does not directly apply to the prescriber. Nevertheless, guidance from the MHRA emphasizes the need for care when prescribers stray from the authorized modes of use.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

The authors are grateful to Professor Stephen Evans, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and to anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Appendix 1.

A brief history of medicines regulation in the UK

Informal licensing of medicines and of individual practitioners to prescribe goes back hundreds of years 2. In 1540 Henry VIII, who had founded the Royal College of Physicians in 1518, promulgated The Pharmacy Wares, Drugs, and Stuffs Act, empowering the physicians to inspect apothecaries' wares and destroy them if defective. This control continued even after 1617, when The Worshipful Society of the Art and Mistery of Apothecaries was founded, but by the start of the eighteenth century the power of the physicians over the apothecaries had waned, and the rights of apothecaries to visit the sick and prescribe medicines, which they were already doing, with little control from the physicians, were established 24.

The establishment of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), following the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act 25, and later the 1938 Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, marked the start of modern medicines regulation in the USA. In the UK, the 1917 Venereal Disease Act imposed the earliest constraint on the marketing of medicines, stipulating that ‘a person shall not hold out or recommend to the public, by any notice or advertisement, or by any written or printed papers or handbills, or by any label or words written or printed, affixed to or delivered with, any packet, box, bottle, phial, … any [formulation] to be used … for the prevention, cure, or relief of any venereal disease’ 26. The 1939 Cancer Act included a similar prohibition 27.

Following the thalidomide affair 28, 29, 30, the Standing Medical Advisory Committee of the Ministry of Health, chaired by Lord Cohen of Birkenhead, advised the establishment of the Committee on Safety of Drugs (CSD) in 1963 31, whose main functions were pre‐marketing scrutiny of new drugs, before they were subjected to clinical trials, and post‐marketing surveillance to monitor adverse drug reactions, document them, and issue appropriate warnings. A report produced by the CSD led to the 1968 Medicines Act, which created a Medicines Commission to advise a Licensing Authority. The Authority was defined as a body of ministers, namely ‘the Minister of Health [in England & Wales], the Secretary of State concerned with health in Scotland and the Minister of Health and Social Services for Northern Ireland’. The Medicines Commission established the Committee on Safety of Medicines (CSM) under Section 4 of the Act, and recommendations from these two bodies were transmitted to the Licensing Authority initially by the Medicines Division within the Ministry (later Department) of Health and then by a secretariat called the Medicines Control Agency (MCA) after its establishment in 1989 32.

In 2003 the MCA and the Medical Devices Agency (MDA) were merged to form the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), with later incorporation of the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC). The Medicines Commission and the CSM have since been jointly replaced by the Commission on Human Medicines (CHM), which now advises the Licensing Authority about drug licensing through the MHRA, which issues all authorizations for medicinal products for human use and licences for manufacturers and wholesalers of such products across the UK. The Licensing Authority is responsible for the grant, renewal, variation, suspension, and revocation of licences and certificates.

The 1968 Medicines Act introduced the UK system whereby applicants are granted licences (now known as Marketing Authorizations, colloquially known as product licences), permitting them to market medicinal products for specified indications under specified conditions. Matters relating to prescribing were later covered by The Prescription Only Medicines (Human Use) Order 1997 33, which partially repealed the 1968 Act. That Order was later mostly revoked by the Human Medicines Regulations 2012 3, which consolidated the law contained in previous instruments and is a UK Statutory Instrument, legislation secondary to the Medicines Act and not itself a full Act.

Appendix 2.

The headings under which information about a medicinal product must be given in the Summary of Product Characteristics by EU law

|

1. Name of the medicinal product 2. Qualitative and quantitative composition 3. Pharmaceutical form 4. Clinical particulars 4.1 Therapeutic indications 4.2 Posology and method of administration 4.3 Contraindications 4.4 Special warnings and precautions for use 4.5 Interaction with other medicinal products and other forms of interaction 4.6 Fertility, pregnancy and lactation 4.7 Effects on ability to drive and use machines 4.8 Undesirable effects 4.9 Overdose |

5. Pharmacological properties 5.1 Pharmacodynamic properties 5.2 Pharmacokinetic properties 5.3 Preclinical safety data 6. Pharmaceutical particulars 6.1 List of excipients 6.2 Incompatibilities 6.3 Shelf life 6.4 Special precautions for storage 6.5 Nature and contents of container 6.6 Special precautions for disposal and other handling 7. Marketing authorization holder 8. Marketing authorization number(s) 9. Date of first authorization/renewal of the authorization 10. Date of revision of the text |

Appendix 3.

The text of the Judgment of the Court (Third Chamber) in the case of the European Commission v. the Republic of Poland

‘By its application, the European Commission asks the Court to declare that, by adopting and maintaining in force Article 4 of the Law on Medicinal Products (Prawo farmaceutyczne) of 6 September 2001, as amended by the Law of 30 March 2007 (Dz. U. No 75, heading 492) (‘the Law on Medicinal Products’), inasmuch as that statutory provision dispenses with the requirement for a marketing authorization for medicinal products from abroad which have the same active substances, the same dosage and the same form as those having obtained a marketing authorization in Poland, on condition that, in particular, the price of those imported medicinal products is competitive in relation to the price of products having obtained such authorization, the Republic of Poland has failed to fulfil its obligations under Article 6 of Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use (OJ 2001 L 311, p. 67), as amended by Regulation (EC) No. 1394/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 November 2007 (OJ 2007 L 324, p. 121) (‘Directive 2001/83’).’

The first subparagraph of Article 6 of Directive 2001/83/EC 4 reads as follows:

‘No medicinal product may be placed on the market of a Member State unless a marketing authorization has been issued by the competent authorities of that Member State in accordance with this Directive or an authorization has been granted in accordance with Regulation (EC) No. 726/2004, read in conjunction with Regulation (EC) No. 1901/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2006 on medicinal products for paediatric use (2) and Regulation (EC) No. 1394/2007.’

The next subparagraph extends an initial marketing authorization granted in accordance with the previous subparagraph to ‘any additional strengths, pharmaceutical forms, administration routes, [or] presentations’.

The final judgment of the court, stated in paragraph 52, was as follows:

‘Consequently, it must be held that, by adopting and maintaining in force Article 4 of the Law on Medicinal Products, inasmuch as that statutory provision dispenses with the requirement for a marketing authorization for medicinal products from abroad which have the same active substances, the same dosage and the same form as those having obtained a marketing authorization in Poland, on condition that, in particular, the price of those imported medicinal products is competitive in relation to the price of products having obtained such authorization, the Republic of Poland has failed to fulfil its obligations under Article 6 of Directive 2001/83.’

Appendix 4.

Providing medicines for ‘special needs’

It is not illegal in the UK for a registered prescriber to prescribe an unlicensed product or a licensed product off‐label. Unlicensed medicines can be supplied by so‐called ‘special order’ manufacturers, who are licensed by the MHRA, obviating the need for a marketing authorization.

However, Appendix 2 in the MHRA's Guidance Note 14 (quoted in full below) advises on priorities in choosing medicinal products to prescribe, as follows, in each case assuming that the earlier choices are not available:

use a licensed product within the terms of its licence (i.e. the label);

use a licensed product off‐label;

use an imported product that has a licence elsewhere;

use a product that is not licensed anywhere, but which has been manufactured in the UK as a ‘special’.

[We have not included here the final piece of guidance relating to products that are not classed as medicines in the country of origin, but are so classed in the UK, as such instances are rare.]

This guidance is of practical importance to prescribers because their responsibility and potential liability in law may be greater when they prescribe a medicine other than in case (a) above 34

Section 2.6 of Guidance Note 14 specifies the conditions under which a manufacturer may supply a ‘special’:

there is an unsolicited order;

the product is manufactured and assembled in accordance with the specification of a person who is a doctor, dentist, nurse independent prescriber, pharmacist independent prescriber or supplementary prescriber registered in the UK;

the product is for use by a patient for whose treatment that person is directly responsible in order to fulfil the special needs of that patient; and

the product is manufactured and supplied under specific conditions [as specified in Appendix 1 of the guidance].

Under Article 5(1) of Directive 2001/83/EC, the requirement to have a national marketing authorization can be waived in the case of ‘special needs’, when the doctor considers that the state of health of an individual patient requires that a medicinal product be administered for which there is no authorized equivalent on the national market or which is unavailable on that market. The Guidance Note (Section 2.2) specifies that ‘An unlicensed medicinal product should not be supplied where an equivalent licensed medicinal product can meet the special needs of the patient. … Examples of ‘special needs’ include an intolerance or allergy to a particular ingredient, or an inability to ingest solid oral dosage forms.’ Furthermore, Section 2.3 specifies that ‘The requirement for a “special need” relates to the special clinical needs of the individual patient. It does not include reasons of cost, convenience or operational needs.’ [emphasis in the original].

Aronson, J. K. , and Ferner, R. E. (2017) Unlicensed and off‐label uses of medicines: definitions and clarification of terminology. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 83: 2615–2625. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13394.

References

- 1. Advanced therapy medicinal products: regulation and licensing. Available at https://www.gov.uk/guidance/advanced‐therapy‐medicinal‐products‐regulation‐and‐licensing (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 2. Penn RG. The state control of medicines: the first 3000 years. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1979; 8: 293–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. The Human Medicines Regulations . 2012. Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2012/1916/pdfs/uksi_20121916_en.pdf (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 4. Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community Code relating to medicinal products for human use (OJ L 311, 28.11.2001, p. 67). Available at http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/eudralex/vol‐1/dir_2001_83_consol_2012/dir_2001_83_cons_2012_en.pdf (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 5. World Health Organization . Marketing authorization of pharmaceutical products with special reference to multisource (generic) products: a manual for drug regulatory authorities – regulatory support series no. 005. Available at http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js2273e/10.html (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 6. European Medicines Agency . Authorisation of medicines. Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/about_us/general/general_content_000109.jsp (last accessed 13 June 2016).

- 7. The Unlicensed Medicinal Products for Human Use (Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies) (Safety) Regulations . 2003. Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2003/1680/pdfs/uksi_20031680_en.pdf (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 8. The Medicines (Homoeopathic Medicinal Products for Human Use) Regulations . 1994. Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1994/105/schedule/2/paragraph/1/made (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 9. European Commission . List of medicinal products authorised under Article 126a of Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community Code relating to medicinal products for human use. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community‐register/html/except_index.htm (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 10. Kaja S, Hilgenberg JD, Everett E, Olitsky SE, Gossage J, Koulen P. Effects of dilution and prolonged storage with preservative in a polyethylene container on bevacizumab (Avastin™) for topical delivery as a nasal spray in anti‐hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia and related therapies. Hum Antibodies 2011; 20: 95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Poku E, Rathbone J, Everson‐Hock E, Essat M, Wong R, Pandor A, et al Bevacizumab in eye conditions: issues related to quality, use, efficacy and safety. Report by the Decision Support Unit, August, 2012. Available at http://www.nicedsu.org.uk/Bevacizumab%20report%20‐%20NICE%20published%20version%2011.04.13.pdf (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 12. MHRA . Off‐label or unlicensed use of medicines: prescribers' responsibilities. 2009. Available at http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/DrugSafetyUpdate/CON087990 (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 13. European Commission Enterprise and Industry Directorate‐General . A guideline on Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). September 2009. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/eudralex/vol‐2/c/smpc_guideline_rev2_en.pdf (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 14. Electronic Medicines Compendium . Bendroflumethiazide. Available at https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/search/?q=Bendroflumethiazide&dt=1 (last accessed 13 June 2016).

- 15. General Medical Council . Good practice in prescribing medicines. 2006. Available at http://www.gmc‐uk.org/Good_Practice_in_Prescribing_Medicines.pdf_25416575.pdf (last accessed 7 May 2017).

- 16. General Medical Council . Good practice in prescribing medicines. September 2008. Available at http://www.gmc‐uk.org/Good_Practice_in_Prescribing_Medicines_0911_withdrawn.pdf_51291115.pdf (last accessed 7 May 2017).

- 17. General Medical Council . Prescribing guidance: prescribing unlicensed medicines. Available at http://www.gmc‐uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/14327.asp (last accessed 6 May 2017).

- 18. General Medical Council . Hot topic: prescribing unlicensed medicines. November 2015. Available at http://www.gmc‐uk.org/guidance/28349.asp (last accessed 7 May 2017).

- 19. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency . Guidance. The supply of unlicensed medicinal products (‘specials’). MHRA Guidance Note 14. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/373505/The_supply_of_unlicensed_medicinal_products__specials_.pdf (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 20. Stevenson T. GMC is criticised for refusing to disclose reasons behind its advice to support prescribing for Lucentis rather than Avastin for wet AMD. Available at http://www.bmj.com/content/350/bmj.h1981/rapid‐responses (last accessed 8 May 2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21. Evans SJW. Why have UK doctors been deterred from prescribing Avastin? Available at http://www.bmj.com/content/350/bmj.h1654/rapid‐responses (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 22. CVRIA . Reports of Cases. ECLI:EU:C:2012:181 1. Judgment of the Court (Third Chamber), 29 March 2012. Available at http://curia.europa.eu/juris/celex.jsf?celex=62010CJ0185&lang1=en&type=TXT&ancre= (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 23. European Medicines Agency . Compassionate use. Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_000293.jsp (last accessed 7 May 2016).

- 24. Cook HJ. The Rose case reconsidered: physicians, apothecaries, and the law in Augustan England. J Hist Med Allied Sci 1990; 45: 527–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hamburg MA. Shattuck lecture. Innovation, regulation, and the FDA. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 2228–2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Venereal Disease Act 1917 (repealed 19.11.1998) . Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo5/7‐8/21/contents (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 27. Cancer Act 1939 . Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo6/2‐3/13/section/4 (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 28. Nilsson R, Sjostrom H. Thalidomide and the Power of the Drug Companies. London: Penguin Books, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 29. The Sunday Times Insight Team , Knightley P. Suffer the Children: The Story of Thalidomide. London: Andre Deutsch, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brynner R, Stephens T. Dark Remedy: The Impact of Thalidomide and Its Revival as a Vital Medicine. New York: Perseus Publishing, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tansey EM, Reynolds LA. The Committee on Safety of Drugs In: Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine, Vol. 1, eds Tansey EM, Catterall PP, Christie DA, Willhoft SV, Reynolds LA. London: Wellcome Trust, 1997; 103–135. Available at https://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/2745 (last accessed 8 May 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 32. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency . Medicines & Medical Devices Regulation: what you need to know. Available at http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/comms‐ic/documents/websiteresources/con2031677.pdf (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 33. The Prescription Only Medicines (Human Use) Order 1997 (SI 1997/1830) . Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1997/1830/introduction/made (last accessed 8 May 2016).

- 34. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency . Off‐label or unlicensed use of medicines: prescribers' responsibilities. Available at https://www.gov.uk/drug‐safety‐update/off‐label‐or‐unlicensed‐use‐of‐medicines‐prescribers‐responsibilities (last accessed 8 May 2016).