Table of Links

| LIGANDS |

|---|

| cobicistat |

This Table lists key ligands in this article that are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 1.

Pregnancy is characterized by several physiological changes (i.e. increased cardiac output, total body water, fat compartment and glomerular filtration rate; decreased plasma albumin concentration; modifications of hepatic drug metabolism) which have an impact on antiretroviral drug exposure. Furthermore, for low hepatic extraction drugs such as elvitegravir (EVG), the interpretation of total drug concentrations is complicated by the fact that pregnancy decreases albumin binding, which is expected to translate into lower total drug concentrations, despite mostly unaffected unbound concentrations (pharmacologically active). Thus, the characterization of antiretroviral drug pharmacokinetics during pregnancy is of utmost importance in order to treat this special population adequately. We report the total and unbound pharmacokinetics of EVG and its booster cobicistat (cobi) in an HIV‐infected woman during the third trimester of pregnancy and 5 weeks postpartum.

The patient, a 37‐year‐old woman, was diagnosed with HIV 15 years ago but received her first antiretroviral treatment, the once daily (QD) single combination pill (Stribild®) EVG/cobi/emtricitabine/tenofovir (150/150/200/300 mg), in May 2014. Her past medical history includes recurrent unexplained miscarriages. The last miscarriage occurred 4 days after switching from Stribild® to darunavir/ritonavir (800/100 mg) combined with emtricitabine (200 mg) and tenofovir (300 mg) QD, a change that was motivated by the limited data on Stribild® safety during pregnancy. After the miscarriage, the treatment was changed back to Stribild® according to the patient's wish. After 8 months, the patient became pregnant and, although no causal link could be proven between the previous episode of miscarriage and protease inhibitor use, it was decided to maintain Stribild®. Given the limited data on the pharmacokinetics of EVG/cobi during pregnancy, we performed a 24‐h pharmacokinetic assessment at 33 weeks of gestational age. The patient gave her written informed consent and the clinical investigation was approved by the ethics committee.

On the morning of the investigational day, the patient took Stribild® with a standardized breakfast, to ensure optimal absorption of EVG; blood samples were then drawn at defined time points. The patient did not receive any comedications which could affect EVG or cobi pharmacokinetics [e.g. inhibitors or inducers of UDP‐glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) or cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, or any divalent cations which can impair EVG absorption]. The total and unbound concentrations of EVG and cobi were quantified using a validated liquid chromatography coupled to a tandem mass spectrometry method [lower limit of quantification for EVG and cobi: 50 and 5 ng ml–1, respectively; mean intra‐assay variability (CV%) for EVG and cobi: 1.2–1.6 and 0.8–2.3, respectively] 2. Ultrafiltration was used to separate the unbound drug fraction as previously reported 3. The pharmacokinetic parameters, calculated using noncompartmental analysis, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for total (A) and unbound (B) elvitegravir and cobicistat plasma concentrations after administration of elvitegravir/cobicistat (150/150 mg) once daily during the third trimester (33 weeks of gestational age calculated from the last menstrual period) and 5 weeks postpartum

| (A) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elvitegravir | Cobicistat | |||||

| PK parameters (total concentrations) | Third trimester | Postpartum | Nonpregnant population 5 | Third trimester | Postpartum | Nonpregnant population |

| C 0h (ng ml –1 ) | 18 | 68 | NA | 3 | 6 | NA |

| C min (ng ml –1 ) | 18 | 61 | 450 ± 260 | 4 | 6 | 50 ± 130 |

| C max (ng ml –1 ) | 1270 | 1352 | 1700 ± 400 | 1054 | 1133 | 1100 ± 400 |

| T max (h) | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3–4 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| AUC 24 (ng*h ml –1 ) | 14 339 | 15 356 | 23 000 ± 7500 | 5972 | 7869 | 8300 ± 3800 |

| T 1/2 (h) | 2.6 | 3.7 | 8.6 (6.1–10.9)a | 2.8 | 2.6 | 3.5 |

| CL/F (l h –1 ) | 10.5 | 9.8 | 7.6 (16.6)b | 25.1 | 19.1 | 16 (41.9)b |

| (B) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elvitegravir | Cobicistat | |||

| PK parameters (unbound concentrations) | Third trimester | Postpartum | Third trimester | Postpartum |

| C 0h (ng ml –1 ) | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 |

| C min (ng ml –1 ) | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 |

| C max (ng ml –1 ) | 5.5 | 3.8 | 25.7 | 31.1 |

| T max (h) | 2.1 | 4.0 | 2.9 | 2.0 |

| AUC 24 (ng*h ml –1 ) | 51 | 40 | 138 | 148 |

| T 1/2 (h) | 4.0 | 5.2 | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| f u (%) c | 0.3d | 0.3d | 2.1 | 1.8 |

AUC24, area under the curve from time of administration to 24 h postdose, calculated by the linear and logarithmic trapezoidal methods; C0h, predose plasma concentration; CL/F, apparent clearance, calculated by dose divided by AUC24; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; Cmin, minimum plasma concentration; fu, fraction unbound, calculated as the ratio of concentration in the filtrate over total concentration in the plasma before ultracentrifugation; PK, pharmacokinetics; T1/2, elimination half‐life; Tmax, time to reach Cmax

Expressed as the median (range)

From Barcelo et al. 11 (between‐subject variability expressed as % coefficient of variation)

Serum albumin was 38 and 44 g l–1 in the third trimester and postpartum, respectively

For comparison, the average elvitegravir fu measured in nonpregnant HIV‐infected patients undergoing routine therapeutic drug monitoring is 0.5 ± 0.26%.

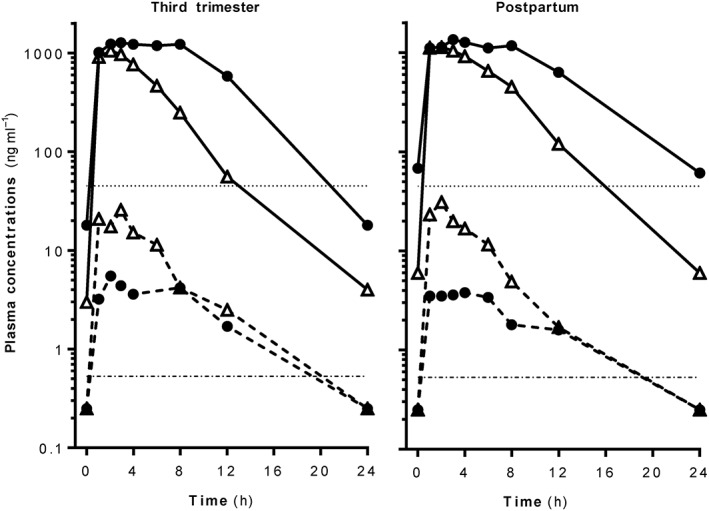

The patient, who remained virologically suppressed throughout pregnancy, gave birth to a healthy HIV‐negative baby girl, weighing 2710 g, via elective Caesarean section at 37 weeks of gestational age. The Apgar scores were 9/10/10 at 1, 5 and 10 min, respectively. EVG total and free concentrations were 515 and 2.5 ng ml–1 in the cord, respectively, and 810 and 2.8 ng ml–1 in the maternal plasma, respectively (9 h after drug intake). The resulting total and free EVG cord‐to‐plasma ratio were 0.64 and 0.9, respectively, suggesting a good placental passage, in agreement with a previous report 4. The patient underwent a second full pharmacokinetic evaluation 5 weeks after delivery (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Total and free elvitegravir (EVG) and cobicistat (cobi) plasma concentrations in a patient during pregnancy and postpartum (closed circles: EVG; open triangles: cobi; continuous lines: total concentrations; dashed lines: free concentrations). The threshold lines represent the EVG concentration inhibiting viral suppression by 95% (IC95 = 45 ng ml–1) and the EVG concentration producing a 90% effective response (EC90 = 0.53 ng ml–1)

When considering the total pharmacokinetic parameters, exposure [area under the curve from time of administration to 24 h postdose (AUC24)], minimal concentration (Cmin) and elimination half‐life (T1/2) of both EVG and cobi were considerably lower during the third trimester of pregnancy than the reference values. Importantly, EVG Cmin was below the protein binding‐adjusted concentration inhibiting viral suppression by 95% (IC95) = 45 ng ml–1] 5. Surprisingly, the AUC24 of EVG changed minimally during the postpartum period compared with pregnancy, and the Cmin of both EVG and cobi remained very low compared with the reference values in a nonpregnant population. The fraction unbound (fu) of EVG was 0.3% during the third trimester and 5 weeks postpartum (serum albumin was 38 and 44 g l–1 in the third trimester and postpartum, respectively, and therefore still within the reference range: 35–52 g l–1). fu was lower than values measured in our reference population [average EVG fu = 0.5% in nonpregnant patients undergoing routine EVG/cobi therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM)]. Consequently, unbound EVG Cmin was <0.5 ng ml–1 (Table 1) and therefore suboptimal, considering that the EVG concentration producing a 90% effective response (EC90) is 0.53 ng ml–1 6.

EVG is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4 and secondarily by glucuronidation via UGT1A1/3. It requires pharmacokinetic boosting by the strong CYP3A4 inhibitor cobi to achieve adequate exposure over a dosing interval 5. Importantly, CYP3A4 and UGT1A1 are induced during pregnancy by female hormones such as progesterone, the level of which rises significantly 7 and which has been shown to upregulate the hepatic expression of drug‐metabolizing enzymes through activation of the nuclear receptor PXR 8, 9. This induction increases the metabolic clearance of both EVG and cobi, and consequently shortens the cobi‐boosting effect, thereby contributing to a lower EVG AUC24 and Cmin. The modest change in EVG pharmacokinetics observed between pregnancy and postpartum, as also reported by others 4, is suggestive of a persisting induction of metabolism, as the effect of hormone‐induced changes might not have decreased to pre‐pregnancy levels 7. Of interest, EVG Cmin and fu were higher (149 ng ml–1 and 0.5%) when remeasured 6 months postpartum in this patient. The decrease in EVG fu during pregnancy is unexpected for a low hepatic extraction drug and considering the observed albumin levels in the third trimester and postpartum. Binding to a carrier protein that increases during pregnancy might be considered as a possible explanation for this finding. In this respect, we have investigated the adsorption of EVG on human sex hormone‐binding globulin, which is known to bind to a variety of chemicals 10; however, our in vitro exploration did not reveal a specific affinity for this carrier (results not detailed).

Unlike what has been described for protease inhibitors, decreased total EVG concentrations during pregnancy are associated with a decrease in the unbound active fraction, resulting in a risk of suboptimal exposure. Therefore, Stribild® should be used with caution in pregnancy, and additional pharmacokinetic and efficacy data are urgently needed.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

The authors thank Ms Béatrice Ternon and Ms Susana Alves Saldanha for their excellent analytical support. We also thank the patient who consented to participate in this study.

Marzolini, C. , Decosterd, L. , Winterfeld, U. , Tissot, F. , Francini, K. , Buclin, T. , and Livio, F. (2017) Free and total plasma concentrations of elvitegravir/cobicistat during pregnancy and postpartum: a case report. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 83: 2835–2838. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13310.

References

- 1. Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SP, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucleic Acids Res 2016; 44 (Database Issue): D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aouri M, Calmy A, Hirschel B, Telenti A, Buclin T, Cavassini M, et al. A validated assay by liquid chromatography‐tandem mass spectrometry for the simultaneous quantification of elvitegravir and rilpivirine in HIV positive patients. J Mass Spectrom 2013; 48: 616–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fayet A, Béguin A, de Tejada BM, Colombo S, Cavassini M, Gerber S, et al. Determination of unbound antiretroviral drug concentrations by a modified ultrafiltration method reveals high variability in the free fraction. Ther Drug Monit 2008; 30: 511–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schalkwijk S, Colbers A, Konopnicki D, Greupink R, Russel FG, Burger D, et al. PANNA network . First reported use of elvitegravir and cobicistat during pregnancy. AIDS 2016; 30: 807–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Podany AT, Scarsi KK, Fletcher CV. Comparative clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of HIV‐1 integrase strand transfer inhibitors. Clin Pharmacokinet 2017; 56: 25–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matsuzaki Y, Watanabe W, Yamataka K, Sato M, Enya S, Kano M, et al JTK‐303/GS‐9137, a novel small molecule inhibitor of HIV‐1 integrase: anti‐HIV activity profile and pharmacokinetics in animals. In: Program and Abstracts of the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Denver, 5–8 February 2006. Abstract 508.

- 7. Pennell KD, Woodin MA, Pennell PB. Quantification of neurosteroids during pregnancy using selective ion monitoring mass spectrometry. Steroids 2015; 95: 24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aweeka FT, Hu C, Huang L, Best BM, Stek A, Lizak P, et al. International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT) P1026s Protocol Team . Alteration in cytochrome P450 3A4 activity as measured by a urine cortisol assay in HIV‐1‐infected pregnant women and relationship to antiretroviral pharmacokinetics. HIV Med 2015; 16: 176–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jeong H, Choi S, Song JW, Chen H, Fischer JH. Regulation of UDP‐glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A1 by progesterone and its impact on labetalol elimination. Xenobiotica 2008; 38: 62–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hong H, Branham WS, Ng HW, Moland CL, Dial SL, Fang H, et al. Human sex hormone‐binding globulin binding affinities of 125 structurally diverse chemicals and comparison with their binding to androgen receptor, estrogen receptor, and α‐fetoprotein. Toxicol Sci 2015; 143: 333–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barcelo C, Gaspar F, Aouri M, Panchaud A, Rotger M, Guidi M, et al. Swiss HIV Cohort Study . Population pharmacokinetic analysis of elvitegravir and cobicistat in HIV‐1‐infected individuals. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016; 71: 1933–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]