Abstract

Masting is the highly variable production of synchronized seed crops, and is a common reproductive strategy in plants. Weather has long been recognized as centrally involved in driving seed production in masting plants. However, the theory behind mechanisms connecting weather and seeding variation has only recently been developed, and still lacks empirical evaluation. We used 12-year long seed production data for 255 holm oaks (Quercus ilex), as well as airborne pollen and meteorological data, and tested whether masting is driven by environmental constraints: phenological synchrony and associated pollination efficiency, and drought-related acorn abscission. We found that warm springs resulted in short pollen seasons, and length of the pollen seasons was negatively related to acorn production, supporting the phenological synchrony hypothesis. Furthermore, the relationship between phenological synchrony and acorn production was modulated by spring drought, and effects of environmental vetoes on seed production were dependent on last year's environmental constraint, implying passive resource storage. Both vetoes affected among-tree synchrony in seed production. Finally, precipitation preceding acorn maturation was positively related to seed production, mitigating apparent resource depletion following high crop production in the previous year. These results provide new insights into mechanisms beyond widely reported weather and seed production correlations.

Keywords: environmental constraint, mast seeding, Moran effect, seed production, phenological synchrony hypothesis, seed abscission

1. Introduction

Masting, or mast seeding, is a common reproductive strategy in perennial plants, characterized by high inter-annual variability in seed production synchronized over large areas [1]. It results in severe fluctuations in food availability for seed-feeding animals producing cascade effects through trophic levels [2,3]. Despite its clear importance, our understanding of the proximate mechanisms driving masting across different taxa remains incomplete [4]. It has long been recognized that resources and weather are centrally involved in driving seed production patterns in masting plants [1,5–8], but it is only recently that attention has turned to the mechanisms linking seed production and weather variability [4,7–13].

Despite masting being a phenomenon that takes place at the population level, it originates at the individual level by combining two processes: inter-annual variability in seed production, and synchronization among individuals. The inter-annual variation in seed production is driven in part by plant resources through preventing individuals from producing sequentially large crops [4,14]. Therefore, weather may affect seed production by affecting plant resource state, e.g. by providing good conditions for photosynthate accumulation [13–16] or by influencing resource remobilization [17,18]. Among-individual synchronization in reproduction is believed to be driven by environmental variation and associated pollination efficiency [4,14]. Plants can similarly respond to a weather signature, such as temperature or rainfall, resulting in synchronized flowering [8,11,19,20]. Synchronized flowering might also be the result of plants reaching a resource threshold as predicted by the resource budget model [16,21]. In such systems, plant populations should show high inter-annual variation in flowering intensity, and seed production should be determined by high flower density and associated high pollination success, i.e. pollen coupling [16,19,22–25]. Alternatively, weather might drive population-wide pollination success and seed maturation rates creating the Moran effect [12,26]. In this case, annual variability in flowering intensity is less important, and flower to fruit transition drives seed production [4,5,19,27,28]. However, the theory behind these mechanisms has only recently been developed, and it largely lacks empirical evaluation [4,14].

Two main hypotheses have been proposed for how the weather conditions may affect the effectiveness of pollen transfer among plants (i.e. the pollination Moran effect). Rainfall during flowering may wash pollen out of the atmosphere and limit pollination success [29]. Alternatively, annual differences in the synchrony of flowering within the population, driven by variation in the spring temperature, may determine pollen availability along with flowering synchrony and thus fertilization success, i.e. the phenological synchrony hypothesis [30]. Irrespective of weather effects on pollination success, weather can affect seed crop size by affecting seed maturation rates [5,28,31], e.g. water stress may lead to high fruit abscission [27,28,32]. Furthermore, environmental veto processes are expected to interact with resource dynamics [4,14]. For example, if reproduction was vetoed in a year (e.g. pollination failure caused by desynchronized flowering), more resources should be available for reproduction during the following year [4,30]. Finally, because environmental vetoes are expected to occur over large spatial scales, they can be considered possible mechanisms behind the large-scale synchrony of seed production observed in masting plants [33,34]. However, we currently know little about how these mechanisms interact to create masting dynamics.

The main aim of this study was to explore whether seed production in a Mediterranean oak is a consequence of two interacting constraints: namely, pollination efficiency driven by phenological synchrony and drought. To reach this aim, we used acorn production data from 255 trees spanning 12 years for Quercus ilex (holm oak), as well as corresponding airborne pollen and meteorological data. We explore how seeding dynamics are related to the number of pollen grains in the air (proxy for flowering intensity), pollen season length (proxy for phenological synchrony), spring water deficit, and summed rainfall in the six months preceding seed maturation. Oaks are thought to be ‘fruit maturation masting species’, i.e. fruit density is largely driven by variable ripening of a much more constant flower crop [4,19,27]. Thus, we hypothesize that phenological synchrony affects pollination success and thus flower to fruit transition [19,30], and similarly water deficit limits seed production [28,35]. Flowering phenology of oaks should be determined by weather, i.e. cold and wet weather create heterogeneous microclimatic conditions and desynchronize plants, leading to long pollen seasons and reproduction failure. By contrast, warm and dry conditions during pollen seasons lead to synchronous pollen release [30]. Summed precipitation preceding seed fall should positively affect seed production through allowing higher accumulation of resources by higher N mineralization or higher photosynthesis [15,17]. Furthermore, if last year's crop size depletes plant resources and negatively affects current reproduction, we expect the effect of precipitation to mitigate it, through allowing more efficient resource rebuilding. Similarly, if reproduction in the previous year was vetoed by pollination failure or drought (as opposed to low resource state), we expect higher reproductive allocation in the next year due to saved resources [4,13]. Finally, we test whether environmental forcing mechanisms, i.e. phenological synchrony and spring water deficit, are related to among-tree variability in seed production dynamics.

2. Material and methods

(a). Study site, species, and seed production data

This study was carried out in the Collserola Massif (41°260′ N, 2°060′ E), northeast Iberian Peninsula. The climate is Mediterranean, characterized by mild winters and dry summers. The mean annual temperature is 15.7 ± 1.4°C and the mean annual precipitation is 613.8 ± 34.0 mm. The holm oak (Q. ilex) is the most widespread tree species of the Iberian Peninsula. It flowers in spring and acorns grow and ripen in the same year, being dropped in autumn–winter. Crop sizes show strong inter-annual fluctuations [27,36].

We monitored acorn production from 1998 to 2009 in 17 sampling sites (255 trees, 15 per plot) in holm-oak-dominated forests (mean distance 4.7 ± 2.4 km, electronic supplementary material, figure S1). The other oak present at the site is deciduous Quercus humilis. Trees were tagged and the number of branches per tree was estimated using a regression model between crown projection and number of branches previously constructed for a subsample of trees [27]. We counted acorn production on four branches per tree at the peak of the acorn crop (i.e. September). Then we estimated the total number of acorns produced per tree by multiplying the mean acorn production per branch and the number of branches per tree (see [27] for details).

(b). Pollen and weather data

We used the pollen data on Quercus evergreen type from the Catalan Aerobiological Network from two sampling stations close to our study area, and representative of the southeastern and northwestern slopes, respectively: Barcelona (41°230′ N, 2°90′ E) and Bellaterra (41°300′ N, 2°60′ E). The pollen grains of evergreen oaks are easily distinguished from deciduous species, thus the presence of Q. humilis in our study area [27] did not interfere with our analyses. We matched acorn collection plots with the nearest pollen monitoring station, i.e. near Barcelona (located in the southeastern slope of Collserola) and near Bellaterra (northwestern slope). This classification resulted in five plots being classified as nearest Barcelona and 12 nearest Bellaterra [37]. Pollen grains were collected by Hirst traps which are designed to record the concentration of atmospheric particles as a function of time [38]. For each year, we derived two parameters from the pollen data, pollen season length, a measure of flowering synchrony and total pollen, a measure of overall pollen abundance (following protocols of [19]). The total pollen represents the sum of all daily pollen counts during the pollen season. We determined the duration of the pollen seasons using the 80% method that assumes the season starts when 10% of the total yearly pollen catch is achieved and ends when 90% is reached [39]. We used total pollen as an index of flower production, assuming that more flowers produce more pollen grains [37,40]. The pollen data collected with pollen traps correspond well with flowering phenology of trees in the field [29,37].

Data on weather were obtained from two weather stations located within 5 km distance from study sites. Based on the raw data, we calculated the spring (April–June) water deficit for each study year (potential evapotranspiration–real evapotranspiration in millimetres [41]).

(c). Statistical analysis

We calculated masting metrics including individual (CVi) and population-level (CVp) coefficients of variation, synchrony within (rw) and among (ra) sites, and lag-1 population-level temporal autocorrelation (ACF1) of total pollen, length of pollen season, and seed crop size [42,43]. We calculated within-site synchrony using Pearson's correlation of all possible pairs of trees in the stand and then calculating the mean of those correlation coefficients. Among-site synchrony was calculated based on all possible pairs of trees.

First, we tested for the relationships between selected weather variables and seed production. We built a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) that included the log-transformed, site-level average of acorn production per tree as response, study site as a random effect and mean maximum temperature during pollen season, average rainfall per day during the pollen season, and summed rainfall preceding acorn maturation (1 January–30 June, hereafter precipJan–Jul) as fixed effects. The rainfall window follows the previous studies that found it best explains the increase in oak leaf area [15]. We also included acorn crop in the previous year to control for the potential effect of resource depletion [42,44], and its interaction with precipJan–Jul to test for the potential faster resource rebuild in wet years. Moreover, we included all possible combinations of two-way interaction terms between the previous year's and current year's mean maximum temperature during pollen season (potential driver of phenological synchrony), and the rainfall during previous and current pollen season (i.e. driver of spring water deficit), i.e. four interaction terms in total. This was done to test for the potential interacting effects of the previous and current year's vetoes on seed production [4,30]. We arrived at the final model structure by removing non-significant interaction terms. We also built a very simple competing model that included difference in temperature between two springs (mean maximum temperature in May) preceding seed fall as a fixed effect (i.e. the ΔT model, cf. [11]). We used temperature in May following past studies conducted on Mediterranean oaks [9,45]. These two models (reduced weather model and ΔT) were compared with each other using the AICc [46]. The veto model outperformed the May ΔT model according to the AICc (ΔAICc = 118.2, d.f. equals 4 in the ΔT, while 12 in veto model).

Next, we tested for the mechanistic underpinnings between weather variables and seed production by asking the following questions: (i) what is the relationship between weather during the pollen season and the duration of the pollen season (i.e. phenological synchrony)? (ii) What is the relationship between weather and total pollen? (iii) How are the pollen parameters, spring water deficit, and conditions during photosynthate accumulation related to seed production? To test questions (i) and (ii), we used regression with the log-transformed length of pollen season (i) or log-transformed total pollen (ii) as response variables, and temperature during pollen season, average rain per day during pollen season, and the interaction term as independent variables. In each of these models, we included the site of pollen collection (Barcelona and Bellaterra) to account for the nested data structure. We addressed the third (iii) question by building a GLMM using a Gaussian family and the identity link. We used log-transformed, average site-level crop size per tree as a response variable and site as a random effect. Fixed effects included length of the pollen season, total pollen, water deficit index, summed rainfall preceding acorn maturation (1 January – 30 June), and acorn crop of the previous year. We also included the following interactions: previous year's crop size × precipJan–Jul, pollen season length × total pollen and all possible two-way interactions between the previous year and current pollen season length, and previous and current year's spring water deficit, to test for the interacting effects of the current and previous year's vetoes, i.e. six interaction terms in total. We arrived at the final model structure by removing non-significant interaction terms.

We tested whether flowering behaviour and water deficit synchronizes among- and within-site seed production. First, we calculated two types of within-year coefficients of variation. Among-site CV was calculated based on site-level means, thus represented among-site variability in seed production. Within-site CV was calculated based on tree-level seed production data for each site and year separately. Thus, it represents the within-year, within-site variability in seed production. First, we tested whether phenological synchrony and water deficit are related to among-site variability in seed production. Here, we used a regression with the length of pollen season, spring water deficit, and their interaction as independent variables, and among-site CV as a response. In the next analysis, we tested whether phenological synchrony and water deficit synchronize trees within the study site. Here, we used a Gaussian family, identity link GLMM with site as a random effect and within-site CV as a response. Fixed effects included length of the pollen season, total pollen, water deficit, and the interaction term between length of the pollen season and water deficit.

We ran all analyses in R, and implemented GLMMs via the lme4 package [47]. Before running mixed models, we standardized and centred variables to facilitate the interpretation of the results: this allowed direct comparisons of effect sizes of different predictors [48]. We checked for collinearity between variables using the variance inflation factor from the ‘AED’ package [49]. We calculated the R2 for linear models, and marginal (i.e. the proportion of variance explained by fixed effects) and conditional (i.e. the proportion of variance explained by fixed and random effects) R2 for GLMMs [50,51]. We also tested for potential spatial autocorrelation in the mean acorn production among plots with Mantel tests and detected none (r = 0.13; p = 0.16).

3. Results

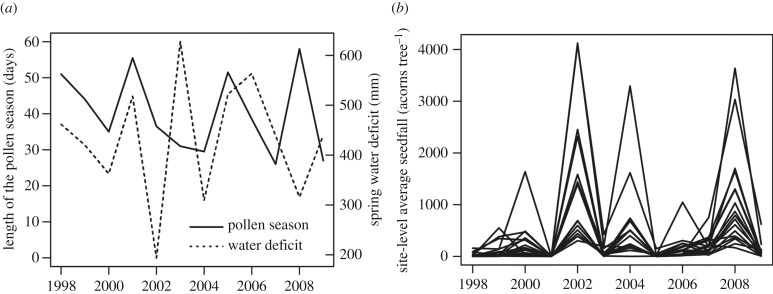

Seed production dynamics of holm oaks in the study site were typical of masting trees, i.e. high inter-annual variation in seed production, both at the population- and the individual-level, and high synchronization (figure 1 and table 1). The CVp of pollen production was one-third as large as the CVp of seed production (table 1), indicating that flower production is relatively constant across years, and it is the flower to fruit transition that generates variation among years in fruit crops (table 2).

Figure 1.

(a) Length of the pollen seasons and spring water deficit during the study duration, (b) site-level average acorn production (acorns per tree) of holm oaks.

Table 1.

Masting metrics for holm oak (Q. ilex) at our study sites. Standard deviations are given in brackets. Mean acorn production is in acorns tree−1 year−1, total pollen is in pollen grains/m3, and length of pollen season is in days.

| species | CVp | CVi | within-site r | among-site r | ACF1 | mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| seed production | 1.46 (0.35) | 2.26 (0.67) | 0.49 (0.15) | 0.41 (0.35) | −0.34 (0.11) | 306.13a (217.56) |

| total pollen | 0.40 | — | — | 0.61b | −0.19 | 3086.66 (1257.98) |

| length of pollen season | 0.27 | — | — | 0.84b | 0.43 | 43.91 (12.13) |

aMean of site-level means.

bCalculated as the Pearson correlation between Barcelona and Bellaterra aerobiological stations.

Table 2.

Summary of predicted relationships, variables tested, apparent mechanisms, and the study results.

| predicted pattern | response variable | mechanism | prediction supported? |

|---|---|---|---|

| inter-annual flowering variability lower than seed variabilitya | total pollen | flower production is relatively constant across years, and it is the flower to fruit transition that generates variation among years in fruit crops | yes |

| seed production not related to flowering intensitya | site-level average acorn production | as above | yes |

| flowering synchrony related to air temperature and rainfall during flowering | pollen season duration | homogeneous conditions during warm and dry pollen seasons enhance flowering synchrony among trees | yes |

| seed production related to flowering synchrony (veto 1) | site-level average acorn production | higher flowering synchrony among trees enhances pollination efficiency | yes |

| seed production related to spring water deficit (veto 2) | site-level average acorn production | high water stress induces acorn abscission | yes |

| accumulated rainfall from January until June enhances seed production | site-level average acorn production | high summed precipitation increases N mineralization and enhances trees photosynthetic capacity allowing higher crop productionb | yes |

| previous year's veto interacts with the current year's veto in driving seed production | site-level average acorn production | passive resource storage: environmental veto prevents resource spending, increasing the resource pool for next year's reproductive allocation | yes |

| environmental veto drives among-site synchrony in seed production | CV of seed production among sites | low water stress allows seed production, decreasing the among-site variation in reproductive output | yes: water stress |

| environmental veto drives within-site synchrony in seed production | CV of seed production among trees, within sites | low water stress and short pollen seasons allow seed production decreasing the among-tree variation in reproductive output | yes: water stress and phenological synchrony |

aWe predicted that oaks will show fruit maturation masting, i.e. seed production will be not related to flower production, but rather will be determined by flower to fruit transition driven by phenological synchrony and drought. Therefore, variability of flower production is expected to be lower than variability of seed production (see also [19]).

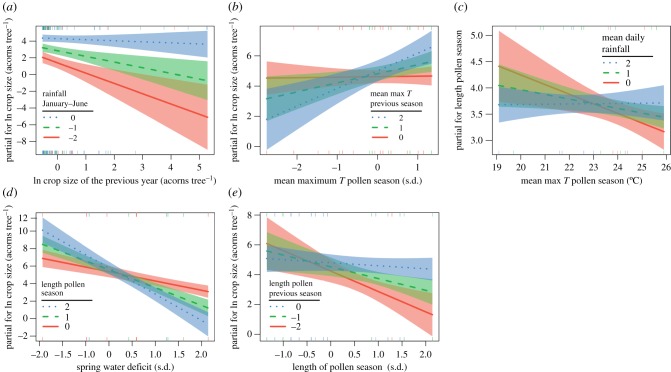

The final model for seed production versus weather included six predictors (the mean max temp during pollen season in year T and year T − 1, the mean daily rain during pollen season in year T and T − 1, the summed rainfall January–June, and the previous year's crop size) and three interaction terms (between temperature during pollen seasons in year T and T − 1, between crop size in year T − 1 and rainfall in January–June in year T, and between temperature during pollen seasons in year T and daily rain during pollen season in year T − 1; electronic supplementary material, table S1(a)). The negative effect of last year's crop size on the current year's seed production was modified by summed rainfall preceding acorn maturation (interaction term: β = 0.55 ± 0.17, p = 0.001), indicating that the negative effect of the last year's crop was cancelled if the current year's seasons were wet enough (figure 2a). The model also included the effect of temperature during the pollen season, although it was modified by last year's temperature during the pollen season (interaction term: β = 0.57 ± 0.13, p < 0.001), i.e. the effect of the current year's spring temperature was positive unless last year's spring was cold, when the slope of the relationship scaled down to 0 (figure 2b). Similarly, the effect of the current year's temperature during the pollen season was modified by last year's average rain during the pollen season (interaction term: β = 0.77 ± 0.14, p < 0.001), i.e. the effect of the current year's spring temperature was positive unless the last year's spring was dry, when the slope scaled down to 0. The interaction term between the current and previous average rainfall during the pollen season was not significant and was removed from the final model (p = 0.27). The variance explained by fixed effects of the model equalled 0.54, while the variance explained by both fixed and random effects was 0.61.

Figure 2.

Interaction plots for the fitted models. Plots show the change in the response of one variable in a two-way interaction term conditional on the value of the other included variable, along with their 95% confidence intervals. (a) Relationship between the current and previous year's crop size conditional on the summed rainfall from January till June. (b) Relationship between the seed crop size and the current year's mean maximum temperature during the pollen season is conditional on the previous year's mean maximum temperature during the pollen season. (c) Relationship between the length of the pollen season and the temperature during the pollen season is conditional on the daily average rain during the pollen season. (d) Relationship between the seed crop size and the spring water deficit is conditional on the length of the pollen season. (e) Relationship between the seed crop size and the length of the pollen season is conditional on the length of the previous year's pollen season. See text for the model details. In cases where interaction plots are based on GLMM (a,b,d,e), the explanatory variables were standardized and axes show standard deviations (s.d.). Response variables (y-axis) are given on the scale of partial residuals. (Online version in colour.)

In agreement with the phenological synchrony hypothesis, the duration of pollen season was negatively related to the average maximum temperature during the pollen season, modified by the average rainfall during that time (interaction term: β = 0.09 ± 0.04, p = 0.03), indicating that the positive relationship between temperature and pollen season length levelled-off once the seasons were wet (R2 = 0.29, figure 2c). None of the explored weather variables affected total pollen (temperature and rain during the pollen season, spring water deficit, all p > 0.10).

The final model for seed production versus environmental vetoes included seven predictors (the length of pollen season in year T and T − 1, the pollen abundance, last year's crop size, the spring water deficit in year T and T − 1, and the rainfall January–June) and three interaction terms (between length of the pollen season in year T and spring water deficit in year T, between length of the pollen season in year T and in year T − 1, and between spring water deficit in year T and in year T − 1; electronic supplementary material, table S1(b) in appendix). In line with the phenological synchrony hypothesis, acorn production was negatively related to pollen season duration, although the effect was strongly dependent on spring water deficit (interaction term: β = −0.97 ± 0.15, p < 0.001, figure 2d), i.e. the crop was lowest when high spring water deficit and long pollen seasons were concurrent. By contrast, the effect of total pollen was not significant (p = 0.10). The effect of the current year's pollen season length was modulated by last year's season length (interaction term: β = 0.58 ± 0.18, p < 0.001), i.e. the effect of the current year's synchrony was only apparent if last year's pollination was allowed (i.e. pollen season was short, figure 2e). Similarly, the effect of the current year's spring water deficit was modulated by the last water deficit (interaction term: β = 0.54 ± 0.24, p = 0.03, graph not shown), i.e. the effect of the current year's deficit was only negative if last year's water deficit was small (i.e. reproduction allowed). Furthermore, summed rain from January to July was positively related to acorn production (β = 0.79 ± 0.20, p < 0.001). In this model, the effect of the crop size of the previous year on crop size was not significant (p = 0.12, R2(m) = 0.64, R2(c) = 0.68). Other interaction terms were insignificant (p > 0.30).

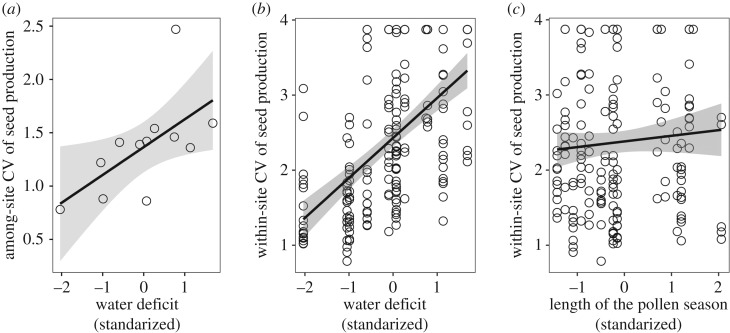

Concerning spatial variation in seed production, among-site CV of seed production was not related to the length of the pollen seasons (p = 0.27), but increased with spring water deficit (β = 0.26 ± 0.10, p = 0.03, R2 = 0.45, figure 3a). Within-site CV of seed production was positively related to both spring water deficit (β = 0.54 ± 0.05, p < 0.001, figure 3b) and length of pollen seasons (β = 0.16 ± 0.06, p = 0.005, R2(m) = 0.35, R2(c) = 0.44, figure 3c). In both among- and within-site CV models, the interaction terms were insignificant.

Figure 3.

The relationship between within-year seed production variability (CV) of holm oaks and the spring water deficit (a,b) and phenological synchrony (c). Trend lines are based on the linear regression (a) and GLMM (b,c), shaded regions represent associated 95% confidence intervals. Points represent measures of CV among sites (a) and among trees within sites (b,c), all within years. Note that the apparent poor fit of the line in (c) is because plots show the raw data, while the model accounts for the spring water deficit and the random effect of study site.

4. Discussion

A summary of our findings (table 2) shows that the Moran effect, in the form of environmental vetoes, i.e. phenological synchrony and associated pollination efficiency together with drought-related fruit abortion, drives mast seeding in Mediterranean oaks. Acorn production was also positively related to summed rainfall preceding acorn maturation, to the extent that it could mitigate the apparent resource depletion following high seed production of the previous year. The likely mechanism is increased N mineralization in wet years [17], and the rapid current year's increase in tree photosynthetic capacity (leaf area) driven by favourable weather conditions [15]. Furthermore, crop size was negatively correlated with the length of pollen seasons, our proxy of phenological synchrony [19], suggesting that pollination efficiency is enhanced in warm years [30]. Moreover, the effect of phenological synchrony was attenuated by last year's veto, suggesting that environmental constraints interact with plant resource state in driving seeding dynamics [4,13].

Weather affects seed production in our system through an interplay of two veto processes, i.e. phenological synchrony and spring drought, with the latter having a stronger effect. Across different oak species, seed production correlates with either rain or temperature in spring [5,9,52–55]. Based on the patterns we observed, we hypothesize that both phenological synchrony and acorn abortion owing to water-shortage occur in oaks, but depending on the local conditions one of them has a stronger effect on seeding dynamics. In water-limited areas, as in our system, drought-driven acorn abscission has a stronger effect on acorn production than phenological synchrony. Therefore, rainfall overrides the temperature-driven phenological synchrony in correlative studies [9,45,52]. By contrast, in mesic forests, pollination efficiency is more important, and thus spring temperature (through synchronization of pollen release) has a stronger effect on seeding dynamics than the rainfall [19]. We expect similar gradients across systems that are similarly water-limited but differ in plant densities. For example, the valley oak (Quercus lobata) in California grows in a Mediterranean, savannah-like landscape, making pollen transfer among individuals constrained [56], and thus highly dependent on the phenological synchrony [10,30]. By contrast, trees at our study site grow in crowded forests (e.g. 1 357 ± 219 stems ha−1 in [37]). This makes outcross pollen more accessible [57], but induces more severe stress in the case of water limitation due to high competition [27,35]. Generally, mechanistic understanding of the influence of weather variables on seeding dynamics will improve our understanding of the key drivers, especially in enigmatic genera like Quercus where consistent links to simple weather signals have not been found.

We also found that the Moran effect in the form of environmental veto (i.e. drought or synchrony-related pollination failure) decreases variability in seed production among trees both within- and among-sites (figure 3). Recently, environmental veto was incorporated into resource budget models, showing that it might be a driver of observed variability and synchrony of seed production [7,10,58]. Our results provide further empirical support for these models, showing that environmental veto is a likely driver of the large-scale synchrony of seed production observed in masting plants [33,34,59,60]. To the extent to which it is true, the spatial synchrony of seeding dynamics should match the spatial synchrony of the veto, a pattern already found in some systems [12,61]. Past theoretical work concluded that environmental noise alone could not drive large-scale spatial synchronization of tree reproduction [62–64]. However, more recent theoretical models showed that if correlated environmental noise is replaced with reproduction failure caused by environmental veto, then large-scale synchronization may apply [58], a result supported by our study.

A previous work relating airborne pollen dynamics to seed production in Q. ilex found that the onset of the flowering season had a strong effect on acorn production, while total pollen did not [37]. Recent advancement of the theoretical understanding of masting dynamics sheds new light on these findings. Lack of the direct relationship between total pollen and acorn production is expected in species in which the flower to fruit transition drives seeding dynamics, because flower density per se should have a smaller effect [4,19]. Therefore, the importance of pollination efficiency is not ruled out, but it is rather driven by different processes, e.g. phenological synchrony [30]. Furthermore, in systems in which the onset of flowering varies strongly (e.g. by 37 days in our study), pollen seasons that start later in the year are likely to be short, because air temperature tends to be higher as summer approaches (see electronic supplementary material, figure S3). With a correlative analysis, it is not possible to distinguish causation, but models including phenological synchrony perform statistically better than those including flowering onset in our data (see electronic supplementary material, table S2). Experimental tests of the pollen limitation across individuals differing in flowering synchrony are crucial to resolve this issue.

5. Conclusion

We found support for a number of theoretical processes proposed to drive the reported correlations between weather and seed production (table 2). The interactive effects of spring vetoes on acorn production outperformed spring weather as a cue model (ΔT model, cf. [11]), supporting the notion that weather affects seed production through direct mechanisms rather than through cues [19,65], at least in oaks [9,19]. This makes masting dynamics susceptible to global climate changes. Recent models for North American oaks showed that inter-annual variability in seed production will likely decrease as a consequence of anticipated warmer springs, associated with more frequent synchronous flowering, and more regular production of smaller seed crops [30]. In the Mediterranean basin, temperatures are predicted to rise while rainfall to decrease, which will increase pollination efficiency, but also increase the occurrence of drought. Therefore, reproduction will likely be vetoed more often, producing a reverse pattern, i.e. less regular production of higher crops. Our results stress the importance of understanding particular mechanisms driving seed production among systems, as different predictions will apply depending on whether the species is a flowering masting one [11,19], or which veto is the most relevant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Catherine Preece for improving our English, and four anonymous reviewers for critical assessment of our article.

Data accessibility

All data used in the study is archived at Dryad: (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.843d1) [66].

Authors' contributions

M.B. conceived the study, designed it, carried out the data analysis, and drafted the manuscript; M.F.-M. designed the study, collected the field data, and helped draft the manuscript; J.B. collected the field data; R.B. collected the field data and helped draft the manuscript, J.M.E. designed the study, collected the field data, and helped draft the manuscript. All authors interpreted the results and gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

M.B. was supported by the (Polish) National Science Foundation grants no. Preludium 2015/17/N/NZ8/01565, and Etiuda no. 2015/16/T/NZ8/00018, and by Foundation for Polish Science scholarship ‘Start’. M.F.-M. was funded by the European Research Council Synergy grant ERC-2013-SyG 610028-IMBALANCE-P. This research was supported by the projects NOVFORESTS (CGL2012-33398), FORASSEMBLY (CGL2015-70558-P) of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and the project BEEMED (SGR913) (Generalitat de Catalunya). R.B. was supported by a contract of the Programme “Atracción de Talento Investigador” (Junta de Extremadura).

References

- 1.Kelly D. 1994. The evolutionary ecology of mast seeding. Trends Ecol. Evol. 9, 465–470. ( 10.1016/0169-5347(94)90310-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostfeld RS, Keesing F. 2000. Pulsed resources and community dynamics of consumers in terrestrial ecosystems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 15, 232–237. ( 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01862-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogdziewicz M, Zwolak R, Crone EE. 2016. How do vertebrates respond to mast seeding? Oikos 125, 300–307. ( 10.1111/oik.03012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearse IS, Koenig WD, Kelly D. 2016. Mechanisms of mast seeding: resources, weather, cues, and selection. New Phytol. 212, 546–562. ( 10.1111/nph.14114) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sork VL, Bramble J, Sexton O. 1993. Ecology of mast-fruiting in three species of North American deciduous oaks. Ecology 74, 528–541. ( 10.2307/1939313) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norton D, Kelly D. 1988. Mast seeding over 33 years by Dacrydium cupressinum Lamb.(rimu) (Podocarpaceae) in New Zealand: the importance of economies of scale. Funct. Ecol. 2, 399–408. ( 10.2307/2389413) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abe T, Tachiki Y, Kon H, Nagasaka A, Onodera K, Minamino K, Han Q, Satake A. 2016. Parameterisation and validation of a resource budget model for masting using spatiotemporal flowering data of individual trees. Ecol. Lett. 19, 1129–1139. ( 10.1111/ele.12651) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monks A, Monks JM, Tanentzap AJ. 2016. Resource limitation underlying multiple masting models makes mast seeding sensitive to future climate change. New Phytol. 10, 419–430. ( 10.1111/nph.13817) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koenig WD, et al. 2016. Is the relationship between mast-seeding and weather in oaks related to their life-history or phylogeny? Ecology 97, 2603–2615. ( 10.1002/ecy.1490) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pesendorfer MB, Koenig WD, Pearse IS, Knops JM, Funk KA. 2016. Individual resource-limitation combined with population-wide pollen availability drives masting in the valley oak (Quercus lobata). J. Ecol. 104, 637–645. ( 10.1111/1365-2745.12554) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly D, et al. 2013. Of mast and mean: differential-temperature cue makes mast seeding insensitive to climate change. Ecol. Lett. 16, 90–98. ( 10.1111/ele.12020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernández-Martínez M, Vicca S, Janssens IA, Espelta JM, Peñuelas J. 2016. The North Atlantic Oscillation synchronises fruit production in western European forests. Ecography 40, 864–874. ( 10.1111/ecog.02296) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rees M, Kelly D, Bjørnstad ON. 2002. Snow tussocks, chaos, and the evolution of mast seeding. Am. Nat. 160, 44–59. ( 10.1086/340603) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crone EE, Rapp JM. 2014. Resource depletion, pollen coupling, and the ecology of mast seeding. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1322, 21–34. ( 10.1111/nyas.12465) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernández-Martínez M, Garbulsky M, Peñuelas J, Peguero G, Espelta JM. 2015. Temporal trends in the enhanced vegetation index and spring weather predict seed production in Mediterranean oaks. Plant Ecol. 216, 1061–1072. ( 10.1007/s11258-015-0489-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crone EE, Polansky L, Lesica P. 2005. Empirical models of pollen limitation, resource acquisition, and mast seeding by a bee-pollinated wildflower. Am. Nat. 166, 396–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smaill SJ, Clinton PW, Allen RB, Davis MR. 2011. Climate cues and resources interact to determine seed production by a masting species. J. Ecol. 99, 870–877. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2011.01803.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanentzap AJ, Lee WG, Coomes DA. 2012. Soil nutrient supply modulates temperature-induction cues in mast-seeding grasses. Ecology 93, 462–469. ( 10.1890/11-1750.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bogdziewicz M, et al. 2017. Masting in wind-pollinated trees: system-specific roles of weather and pollination dynamics in driving seed production. Ecology 98, 2615–2625. ( 10.1002/ecy.1951) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schauber EM, et al. 2002. Masting by eighteen New Zealand plant species: the role of temperature as a synchronizing cue. Ecology 83, 1214–1225. ( 10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083%5B1214:MBENZP%5D2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satake A, Iwasa YOH. 2000. Pollen coupling of forest trees: forming synchronized and periodic reproduction out of chaos. J. Theor. Biol. 203, 63–84. ( 10.1006/jtbi.1999.1066) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith CC, Hamrick J, Kramer CL. 1990. The advantage of mast years for wind pollination. Am. Nat. 136, 154–166. ( 10.1086/285089) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly D, Hart DE, Allen RB. 2001. Evaluating the wind pollination benefits of mast seeding. Ecology 82, 117–126. ( 10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082%5B0117:ETWPBO%5D2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rapp JM, McIntire EJ, Crone EE. 2013. Sex allocation, pollen limitation and masting in whitebark pine. J. Ecol. 101, 1345–1352. ( 10.1111/1365-2745.12115) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreira X, Abdala-Roberts L, Linhart YB, Mooney KA. 2014. Masting promotes individual-and population-level reproduction by increasing pollination efficiency. Ecology 95, 801–807. ( 10.1890/13-1720.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koenig WD. 2002. Global patterns of environmental synchrony and the Moran effect. Ecography 25, 283–288. ( 10.1034/j.1600-0587.2002.250304.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Espelta JM, Cortés P, Molowny-Horas R, Sánchez-Humanes B, Retana J. 2008. Masting mediated by summer drought reduces acorn predation in Mediterranean oak forests. Ecology 89, 805–817. ( 10.1890/07-0217.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pérez-Ramos I, Ourcival J, Limousin J, Rambal S. 2010. Mast seeding under increasing drought: results from a long-term data set and from a rainfall exclusion experiment. Ecology 91, 3057–3068. ( 10.1890/09-2313.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.García-Mozo H, Gómez-Casero M, Domínguez E, Galán C. 2007. Influence of pollen emission and weather-related factors on variations in holm-oak (Quercus ilex subsp. ballota) acorn production. Environ. Exp. Bot. 61, 35–40. ( 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2007.02.009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koenig WD, Knops JM, Carmen WJ, Pearse IS. 2015. What drives masting? The phenological synchrony hypothesis. Ecology 96, 184–192. ( 10.1890/14-0819.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montesinos D, García-Fayos P, Verdú M. 2012. Masting uncoupling: mast seeding does not follow all mast flowering episodes in a dioecious juniper tree. Oikos 121, 1725–1736. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2011.20399.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogaya R, Penuelas J. 2007. Species-specific drought effects on flower and fruit production in a Mediterranean holm oak forest. Forestry 80, 351–357. ( 10.1093/forestry/cpm009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly D, Sork VL. 2002. Mast seeding in perennial plants: why, how, where? Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 33, 427–447. ( 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.020602.095433) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koenig WD, Knops JM. 2013. Large-scale spatial synchrony and cross-synchrony in acorn production by two California oaks. Ecology 94, 83–93. ( 10.1890/12-0940.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanchez-Humanes B, Espelta JM. 2011. Increased drought reduces acorn production in Quercus ilex coppices: thinning mitigates this effect but only in the short term. Forestry 84, 73–82. ( 10.1093/forestry/cpq045) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Espelta JM, Arias-LeClaire H, Fernández-Martínez M, Doblas-Miranda E, Muñoz A, Bonal R. 2017. Beyond predator satiation: masting but also the effects of rainfall stochasticity on weevils drive acorn predation. Ecosphere 8, e01836 ( 10.1002/ecs2.1836) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernández-Martínez M, Belmonte J, Espelta JM. 2012. Masting in oaks: disentangling the effect of flowering phenology, airborne pollen load and drought. Acta Oecol. 43, 51–59. ( 10.1016/j.actao.2012.05.006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheifinger H, et al. 2013. Monitoring, modelling and forecasting of the pollen season. In Allergenic pollen (eds Sofiev M, Bergmann KC), pp. 71–126. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldberg C, Buch H, Moseholm L, Weeke ER. 1988. Airborne pollen records in Denmark, 1977–1986. Grana 27, 209–217. ( 10.1080/00173138809428928) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ranta H, Hokkanen T, Linkosalo T, Laukkanen L, Bondestam K, Oksanen A. 2008. Male flowering of birch: spatial synchronization, year-to-year variation and relation of catkin numbers and airborne pollen counts. For. Ecol. Manag. 255, 643–650. ( 10.1016/j.foreco.2007.09.040) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thornthwaite C. 1948. An approach toward a rational classification of climate. Geo. Rev. 38, 49–123. ( 10.2307/210739) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koenig WD, Kelly D, Sork VL, Duncan RP, Elkinton JS, Peltonen MS, Westfall RD. 2003. Dissecting components of population-level variation in seed production and the evolution of masting behavior. Oikos 102, 581–591. ( 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12272.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crone EE, McIntire EJ, Brodie J. 2011. What defines mast seeding? Spatio-temporal patterns of cone production by whitebark pine. J. Ecol. 99, 438–444. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2010.01790.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crone EE, Miller E, Sala A. 2009. How do plants know when other plants are flowering? Resource depletion, pollen limitation and mast-seeding in a perennial wildflower. Ecol. Lett. 12, 1119–1126. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01365.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pérez-Ramos IM, Padilla-Díaz CM, Koenig WD, Maranon T. 2015. Environmental drivers of mast-seeding in Mediterranean oak species: does leaf habit matter? J. Ecol. 103, 691–700. ( 10.1111/1365-2745.12400) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. 2002. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. Berlin, Germany: Springer Science, Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R Core Team. 2017. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 3.1-131, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme.

- 48.Schielzeth H. 2010. Simple means to improve the interpretability of regression coefficients. Methods Ecol. Evol. 1, 103–113. ( 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2010.00012.x). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Elphick CS. 2010. A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods Ecol. Evol. 1, 3–14. ( 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2009.00001.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakagawa S, Schielzeth H. 2013. A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4, 133–142. ( 10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00261.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bartoń K. 2016. MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference. R package version 1.15.6. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn.

- 52.Koenig WD, Knops JM. 2014. Environmental correlates of acorn production by four species of Minnesota oaks. Pop. Ecol. 56, 63–71. ( 10.1007/s10144-013-0408-z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cecich RA, Sullivan NH. 1999. Influence of weather at time of pollination on acorn production of Quercus alba and Quercus velutina. Can. J. For. Res. 29, 1817–1823. ( 10.1139/x99-165) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang YY, Zhang J, LaMontagne JM, Lin F, Li BH, Ye J, Yuan ZQ, Wang XG, Hao ZQ. 2017. Variation and synchrony of tree species mast seeding in an old-growth temperate forest. J. Veg. Sci. 28, 413–423. ( 10.1111/jvs.12494) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pons J, Pausas JG. 2012. The coexistence of acorns with different maturation patterns explains acorn production variability in cork oak. Oecologia 169, 723–731. ( 10.1007/s00442-011-2244-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sork VL, Davis FW, Smouse PE, Apsit VJ, Dyer RJ, Fernandez MJ, Kuhn B. 2002. Pollen movement in declining populations of California Valley oak, Quercus lobata: where have all the fathers gone? Mol. Ecol. 11, 1657–1668. ( 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01574.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ortego J, Bonal R, Munoz A, Aparicio JM. 2014. Extensive pollen immigration and no evidence of disrupted mating patterns or reproduction in a highly fragmented holm oak stand. J. Plant Ecol. 7, 384–395. ( 10.1093/jpe/rtt049) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bogdziewicz M, Steele MA, Marino S, Crone EE. 2017. Correlated seed failure as an environmental veto to synchronize reproduction of masting plants. bioRxiv ( 10.1101/171579) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koenig WD, Knops JM. 1998. Scale of mast-seeding and tree-ring growth. Nature 396, 225–226. ( 10.1038/24293) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lyles D, Rosenstock TS, Hastings A, Brown PH. 2009. The role of large environmental noise in masting: general model and example from pistachio trees. J. Theor. Biol. 259, 701–713. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.04.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koenig WD, Knops JM. 2000. Patterns of annual seed production by northern hemisphere trees: a global perspective. Am. Nat. 155, 59–69. ( 10.1086/303302) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Satake A, Iwasa Y. 2002. Spatially limited pollen exchange and a long-range synchronization of trees. Ecology 83, 993–1005. ( 10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083%5B0993:SLPEAA%5D2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Satake A, Iwasa Y. 2002. The synchronized and intermittent reproduction of forest trees is mediated by the Moran effect, only in association with pollen coupling. J. Ecol. 90, 830–838. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.00721.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iwasa Y, Satake A. 2004. Mechanisms inducing spatially extended synchrony in mast seeding: the role of pollen coupling and environmental fluctuation. Ecol. Res. 19, 13–20. ( 10.1111/j.1440-1703.2003.00612.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pearse IS, Koenig WD, Knops JM. 2014. Cues versus proximate drivers: testing the mechanism behind masting behavior. Oikos 123, 179–184. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2013.00608.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bogdziewicz M, Fernández-Martínez M, Bonal R, Belmonte J, Espelta JM. 2017. Data from: The Moran effect and environmental vetoes: phenological synchrony and drought drive seed production in a Mediterranean oak Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.843d1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Bogdziewicz M, Fernández-Martínez M, Bonal R, Belmonte J, Espelta JM. 2017. Data from: The Moran effect and environmental vetoes: phenological synchrony and drought drive seed production in a Mediterranean oak Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.843d1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used in the study is archived at Dryad: (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.843d1) [66].