Abstract

BACKGROUND

Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded Medicaid access, it is unknown whether this has led to greater access to complex surgical care. Evidence on the effect of Medicaid expansion on access to surgical cancer care, a proxy for complex care, is sparse. Using New York’s 2001 statewide Medicaid expansion as a natural experiment, we investigated how expansion affected use of surgical cancer care among beneficiaries overall and among racial minorities.

STUDY DESIGN

From the New York State Inpatient Database (1997 to 2006), we identified 67,685 nonelderly adults (18 to 64 years of age) who underwent cancer surgery. Estimated effects of 2001 Medicaid expansion on access were measured on payer mix, overall use of surgical cancer care, and percent use by racial/ethnic minorities. Measures were calculated quarterly, adjusted for covariates when appropriate, and then analyzed using interrupted time series.

RESULTS

The proportion of cancer operations paid by Medicaid increased from 8.9% to 15.1% in the 5 years after the expansion. The percentage of uninsured patients dropped by 21.3% immediately after the expansion (p = 0.01). Although the expansion was associated with a 24-case/year increase in the net Medicaid case volume (p < 0.0001), the overall all-payer net case volume remained unchanged. In addition, the adjusted percentage of ethnic minorities among Medicaid recipients of cancer surgery was unaffected by the expansion.

CONCLUSIONS

Pre-ACA Medicaid expansion did not increase the overall use or change the racial composition of beneficiaries of surgical cancer care. However, it successfully shifted the financial burden away from patient/hospital to Medicaid. These results might suggest similar effects in the post-ACA Medicaid expansion.

Medicaid expansion, a keystone of Affordable Care Act (ACA), was enacted to improve access to high-quality care for the poorest Americans. Specifically, the ACA’s Medicaid provides access to all nonelderly Americans (aged 18 to 64 years) with income <133% of the federal poverty line.1 With the Supreme Court ruling that made Medicaid expansion optional for states, only 32 states, including the District of Columbia, have adopted this provision so far. To date, emerging reports have shown a substantial decrease in the number of the uninsured, and an increase in use of preventive and mental health services.2 Despite these documented benefits, critics have expressed concerns about this policy’s costs, uncertain effect on access to and outcomes after care, and its continuingly low reimbursement rates for hospitals and providers.3–5

Currently, the impact of post-ACA Medicaid expansion on surgical cancer care is largely unknown. Surgical care is complex and costly due to intensity of therapies, which can be more complicated by the burden of comorbidities on Medicaid beneficiaries, and the challenges brought by regionalization of cancer surgery.6,7 In October 2001, New York expanded adult Medicaid via the Family Health Plus Program to provide healthcare coverage to childless nondisabled adults earning up to 100% of federal poverty level and parents of dependent children with income up to 150% federal poverty level. As such, this expansion represents one of the largest health insurance expansions for nonelderly adults in the history of the US.

Because of its features comparable with ACA’s Medicaid expansion, previous studies have used New York as a seminal state to evaluate potential effects of Medicaid expansion on access to surgery. Published surgical reports from New York’s pre-ACA expansion showed >9% increase in use of elective orthopaedic surgery and a 4.5% decrease in nonelective surgical procedures.8,9 However, little is known about Medicaid expansion’s impact on surgical cancer care, and the empirical effect of the post-ACA expansion’s effect would remain largely unknown until administrative data become available a few years later.

Our objective is to generate evidence-based expectations on the potential impact of the ACA Medicaid expansion on access to surgical cancer care through quantifying the effect of the New York pre-ACA Medicaid expansion. In particular, we explore the policy’s potential racial implications. The NIH and American College of Surgeons have jointly prioritized access to care and insurance status as critical research areas to reduce surgical disparities.10 We hypothesize that pre-ACA Medicaid expansion increased use and improved access to surgical care. In this regard, we will quantify the impact of New York’s pre-ACA Medicaid expansion on various measures of use and access to surgical cancer care to its beneficiaries overall. Given that this Medicaid expansion coverage was intended to benefit the most vulnerable populations, we will also examine its impact on access to surgical cancer care among 3 major racial/ethnic groups—non-Hispanic whites, African-Americans, and Hispanics.

METHODS

Data source and study population

As explained, and to inform the impact of the ACA on surgical cancer care, we used the State Inpatient Database from New York in the 5 years before and after the 2001 Medicaid expansion (1997 to 2006). The State Inpatient Database is provided by the AHRQ through Health Care Utilization Project. All discharges from nonfederal acute care hospitals are included in the State Inpatient Database in a given year. We selected patients who underwent cancer surgery and are linked to either screening and prevention or strong volume to operative outcomes relationship. These procedures included those involving the lungs, esophagus, stomach, liver, pancreas, colon, rectum, kidneys, or urinary bladder, and diagnosis of neoplasm on the same discharge record as the surgery. To focus our study on patients most likely affected by Medicaid policies, we included only nonelderly adults aged 19 to 64 years old. In total, our analytic sample included 67,685 patients.

Outcomes variables and covariates

Our main outcomes (dependent) variable is access to surgical cancer. In line with the National Healthcare Quality Report’s measures for access to healthcare, such as having health insurance and successful receipt of needed services,11 we examined access in terms of use of cancer surgery and market share of cancer surgery. To examine whether patients of different race/ethnicity backgrounds were differentially affected by the expansion, we also measured the racial/ethnic composition of recipients of surgical cancer care.

The first outcomes variable we examined was use of cancer surgery, defined as the unadjusted number of cancer surgery cases performed in the state of New York. All-payer total and payer-specific totals were both examined. For payer-specific totals, we selected Medicaid, uninsured (self-pay), and private insurance as the 3 primary payer types of interest.

The second outcomes variable was the market share of cancer surgery, defined as the probability of a cancer surgery being paid by each primary payer type of interest. These probabilities were adjusted for patient’s age, sex, race/ethnicity, and type of procedure.

The third outcomes variable was the racial/ethnic composition of the cancer surgery patients, defined as adjusted percentages of 3 major race/ethnicities (ie non-Hispanic whites, African Americans, and Hispanics) among all eligible patients. This variable was examined among all patients and among Medicaid beneficiaries alone. We examined this variable to evaluate whether gained access to cancer surgery was proportionate among racial/ethnic groups. These percentages were estimated with adjustment for age, sex, and type of procedure.

Independent variable

The independent variable of interest of this study is time of the cancer surgery, dichotomized into before and after the Medicaid expansion (January 1997 to September 2001 vs October 2001 to December 2006).

Statistical methods

We used interrupted time series (ITS)12 to evaluate the impact of the expansion. Interrupted time series is a widely used robust quasi-experimental method that seeks to determine the impact of a specific intervention. The impact is estimated by changes in the outcomes around time of the intervention, after accounting for the pre-existing time trend before the intervention.

The ITS method requires 1 data point per time unit. In this study, we used 3-month periods (quarters) as time units, and each quarter was represented by 1 aggregated data point. For use, these data points were the total number of cases during each quarter. For payer and racial/ethnic percentages, we used regression techniques to generate an estimated average of each end point of interest during each 3-month period (quarter). These estimates are predicted from logistic models that adjusted for applicable covariates.

After transforming the original data into quarterly data points, we used ITS to estimate effect associated with the expansion. Each model included 3 basic terms: the first one measures pre-existing time trend (initial slope) in the data before the expansion; the second represents immediate change in the data after the expansion (change in intercept); and the last measures change in the pre-existing time trend after the expansion (change in slope). The latter 2 terms both represent effect of the expansion. We fitted each model with autoregressive moving average models to account for underlying structure of the time series data and tested the adequacy of each model by white noise tests.13 Seasonality terms were included in the model as necessary. All tests were 2-sided and used a significance level of 0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the distribution of procedure type and demographic characteristics among nonelderly patients of cancer surgery. Colectomy accounted for 36.8% of the entire sample, followed by nephrectomy (18.3%) and lung resections (16.5%). The majority of the sample (74.6%) were older than 50 years of age. African-American and Hispanic patients comprised 11.7% and 5.8% of the sample, respectively. More than three-quarters of the operations were paid for through private insurance (76.5%), 11.5% through Medicaid, and 3.4% were self-pay. Forty-five percent (45.4%) of the patients were female.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Nonelderly Adults Who Underwent Surgical Cancer Care in New York, State Inpatient Database, 1997 to 2006 (N = 67,685)

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Type of cancer resection | ||

| Lung | 11,180 | 16.5 |

| Esophageal | 1,228 | 1.8 |

| Gastric | 3,343 | 4.9 |

| Colon | 24,918 | 36.8 |

| Rectal | 8,464 | 12.5 |

| Liver | 1,295 | 1.9 |

| Pancreas | 2,981 | 4.4 |

| Kidney | 12,386 | 18.3 |

| Bladder | 1,890 | 2.8 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 36,941 | 54.6 |

| Female | 30,708 | 45.4 |

| Age group | ||

| 19 to 34 y | 2,162 | 3.2 |

| 35 to 49 y | 15,035 | 22.2 |

| 50 to 64 y | 50,488 | 74.6 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 45,945 | 67.9 |

| Black | 7,925 | 11.7 |

| Hispanic | 3,896 | 5.8 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 2,111 | 3.1 |

| Primary payer | ||

| Medicare | 4,711 | 7.0 |

| Medicaid | 7,796 | 11.5 |

| Private insurance | 51,779 | 76.5 |

| Uninsured | 2,268 | 3.4 |

Use of cancer surgery

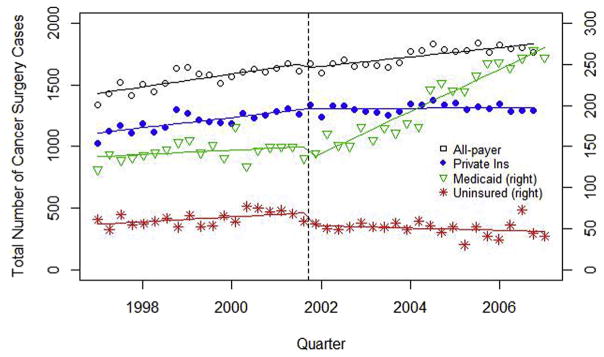

Figure 1 exhibits trends in the all-payer and payer-specific use of cancer surgery. During the study period, quarterly all-payer use in New York started at 1,420 cases and increased by 13.4 cases per quarter (95% CI 9.2 to 16.9). No significant changes were observed due to the Medicaid expansion (both p > 0.05). However, we identified significant shifts in payer-specific use after the expansion. Quarterly number of uninsured cases decreased by 14.9 immediately after the expansion (95% CI 5.3 to 24.4; p = 0.007) and continued to decrease by 1.1 per quarter in the following 5 years (95% CI 0.3 to 1.9; p = 0.02). Quarterly number of private-insurance-paid cases also declined by 9.6 per quarter after the expansion (95% CI 5.2 to 14.0; p = 0.0004). In addition, although a decrease of 18.3 in quarterly Medicaid-paid cases (95% CI 4.2 to 32.4; p = 0.03) was observed immediately after the expansion, it was followed by a quarterly increase of 5.9 cases per quarter in the 5 post-expansion years (95% CI 4.7 to 7.1; p < 0.0001), resulting in a net increase in Medicaid-paid cases in the post-expansion period. Between the time of expansion and the end of our study period, quarterly number of Medicaid-paid major cancer surgery increased from 150 to 270 (difference = 120; 95% CI 105 to 135; p < 0.0001), and quarterly number of self-paid cases decreased from 69 to 47 (difference = 22; 95% CI 12 to 32; p < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

Time trend in use of surgical cancer care by primary payer type in New York, State Inpatient Database, 1997 to 2006.

Market share of payers for cancer surgery

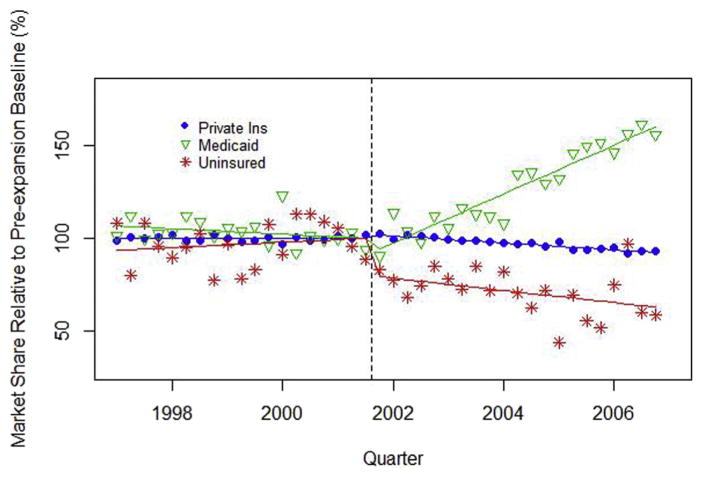

Trends in the market share of each payer for cancer surgery resemble those in payer-specific use. Before the expansion, the market share of each payer was relatively stable—none of the primary payers’ time trends was significant. The probability of the surgery being self-paid decreased by 25.2% immediately after the expansion (95% CI 6.0% to 44.3%; p = 0.01); its quarterly decrease after the expansion was, however, not significant (p = 0.08).

Medicaid’s market share increased by 3.9% per quarter (95% CI 3.0% to 4.7%; p < 0.0001), and private insurance decreased by 0.48% immediately (95% CI 0.34 to 0.61; p < 0.0001), relative to their respective pre-expansion market share, after the expansion. In the 5 years after the expansion, the market share of Medicaid increased from 9.4% to 15.1% (difference = 5.7%; 95% CI 4.8% to 6.5%; p < 0.0001), private insurance decreased from 78.4% to 72.5% (difference = 6.0%; 95% CI 4.8 to 7.1), and self-pay from 4.0% to 2.6% (difference = 1.5%; 95% CI 0.9% to 2.1%; p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Time trend in relative adjusted market share (adjusted for age, sex, race, and procedure type) of primary payer types for major cancer surgery in New York, State Inpatient Database, 1997 to 2006.

Racial/ethnic composition among recipient of cancer surgery

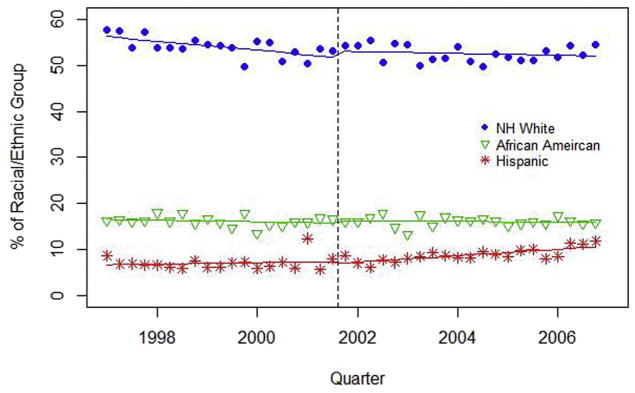

Overall adjusted percentage of non-Hispanic whites among cancer surgery patients started at 56.2% and decreased by 0.25 percentage points per quarter before the expansion (95% CI 0.10% to 0.39%; p = 0.002). This percentage did not change significantly after the Medicaid expansion. The adjusted percentage of African Americans was 16.5% at the beginning of the study and remained stable during the entire study period. Hispanics comprised 7.0% of the cancer surgery patients, and this percentage increased significantly by 0.21 percentage point per quarter after the expansion (95% CI 0.11 to 0.31; p = 0.0002). By the end of the study period, 10.6% of cancer surgery patients were Hispanic (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Time trend in adjusted percentages (adjusted for age, sex, and procedure type) of major race/ethnicity groups among patients of major cancer surgery in New York, State Inpatient Database, 1997 to 2006. NH, non-Hispanic.

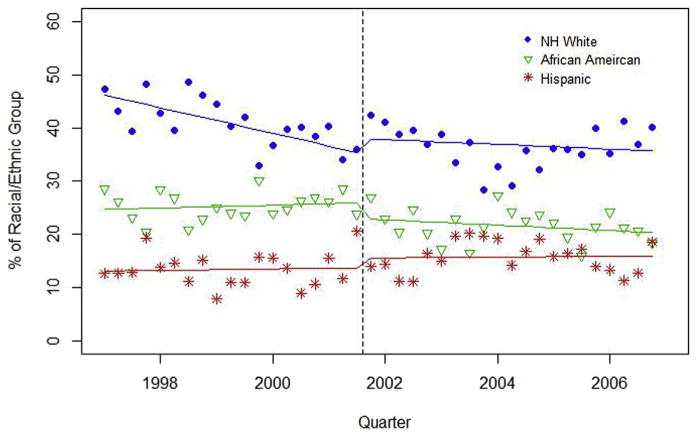

Among Medicaid beneficiaries only, the baseline adjusted percentages of non-Hispanic whites, African Americans, and Hispanics were 46.2%, 24.7%, and 13.1%, respectively. The adjusted proportion of non-Hispanic whites decreased by 0.60 percentage points per quarter before the expansion (95% CI 0.23 to 0.97; p = 0.003). However, the expansion was not associated with any significant changes in the adjusted probability of a cancer surgery patient being non-Hispanic white, African-American, or Hispanic (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Time trend in adjusted proportions (adjusted for age, sex, and procedure type) of major race/ethnicity groups among Medicaid Patients of major cancer surgery in New York, State Inpatient Database, 1997 to 2006. NH, non-Hispanic.

DISCUSSION

Results from one of the largest pre-ACA Medicaid expansion coverage areas demonstrate that such expansion increases access to surgical cancer care significantly. However, it did not increase the overall use or change the racial composition of Medicaid beneficiaries who receive surgical cancer care. Instead, the policy successfully shifted the financial cost away from patients and hospitals to Medicaid. Based on these results, we anticipate that the ACA’s Medicaid expansion can have similar effects on access to surgical cancer care.

In line with our findings, studies from pre-ACA Medicaid expansion in Arizona, New York, Massachusetts, and Oregon have all shown a decrease in the number of uninsured and increase access to healthcare. Medicaid expansions in New York, Maine, and Arizona have decreased uninsurance by 25% and increased Medicaid coverage by15%.14 In addition, a 7.2% increase was noted in breast reconstructions and panniculectomies in the State of New York after Medicaid expansion in 2001.15 Together, our results and those of others reinforce the notion that expansion coverage will lead to increased access to specialty surgical care.

The current appraisal revealed that the expansion did not significantly change the total number of cancer surgery cases performed in New York. This is an important finding, which indicates that the increase in Medicaid cases observed was not due to new demand driven by the expansion. We attribute this finding to 2 plausible explanations. First, the critical and potentially life-saving nature of cancer surgery makes it less market-driven and therefore not sensitive to changes in payment methods, compared with procedures such as elective knee replacement.9 Similar trends were also observed after the Massachusetts state expansion.16 Second, the increase in Medicaid-paid cases was not enough to compensate for the decrease in private insurance cases. The decrease in the inflation-adjusted reimbursement rate for elective surgery from New York Medicaid program, during most of our study period, did not appear to have motivated providers to replace all of their private insurance cases with Medicaid cases.17,18

The disproportional incline in Medicaid-paid cancer surgery vs decline in the uninsured (or unpaid) cancer surgery cases is also noteworthy. The genesis of this phenomenon can be explained by several important events and policy changes specific to the State of New York.19 First and although New York’s 2001 expanded Medicaid covered up to 150% of the federal poverty line in adults with dependent children, this robust expansion does not cover all of the uninsured. Second, New York underwent a period of recession from 2001 to 2003, which has decreased many New Yorkers’ family income and made them eligible for Medicaid. Third, the Disaster Relief Medicaid established in New York City after the 9/11 attack was designed to expedite Medicaid eligibility and enrollment process. Fourth, there is no evidence of rising incidence of surgical cancer cases in the State of New York during our study period. Together, our findings showed a substantial and instantaneous decrease in number of uninsured cases. In the absence of Medicaid expansion, we speculate that this number would likely remain unchanged—a similar group of people would continue to receive surgery despite having no insurance.

Contrary to our expectations, we found no differential effect on access to surgical cancer care among African-American and Hispanic Medicaid beneficiaries vs white Medicaid beneficiaries. This observation is of concern, because expansion of insurance for the poor should, in theory, benefit disadvantaged groups more than other groups and contribute to reducing disparity in healthcare access. To our knowledge, this observation represents one of the first reports in surgery on lack of differential effect of Medicaid expansion on the most vulnerable of the low-income population. We speculate that this lack of differential benefit for minorities might be due to additional obstacles to receiving surgical cancer care beyond having insurance coverage, such as selective referral patterns. This finding points toward potential inadequacy of Medicaid expansion policies in addressing racial disparities in access to tertiary care. Beyond these speculations, this finding warrants additional investigation to provide detailed explanations.

Our results should be interpreted with the following limitations in addition to the inherent biases of retrospective cohort studies. First, we did not use a “nonexpanded” state to serve as a control, which means trends observed in our study can be confounded by other events during the study period. However, changes in Medicaid use and the decrease in uninsured cases observed in this study are pronounced and completely in line with the policy goals of Medicaid expansion. Therefore, we think these observed results are likely attributable to the policy. Second, results from New York’s pre-ACA expansion might not be applicable to all the states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA. Third, our results did not measure or account for the preferences of a Medicaid-eligible person to opt in (or out) of the Medicaid program. Despite these shortcomings, the current study presents the following strengths: use of a quasi-experimental design to estimate effects of the expansion while controlling for pre-existing trends in the study population from 2001, use of the pre-ACA Medicaid expansion in New York as a natural experiment with characteristics comparable with the post-ACA expansion, New York State also has a heterogeneous population and diverse geography, making the study result useful to extrapolate to national estimates, and studying surgical cancer procedures that are either linked to prevention/screening programs (colorectal) or centralized to high-quality hospitals due to the known strong hospital volume to operative outcomes relationship (eg esophagus, pancreas, stomach, and urinary bladder).

Results from the current study have timely and relevant implications. First, given the centralized nature of surgical cancer care, understanding the effects of expansion coverages on access to high-quality hospitals will become increasingly important, especially given concerns for minority “crowd out” from high-volume hospitals.6,7 Second, although Medicaid expansion has drastically improved access to surgical cancer care, it remains to be investigated whether this will translate into improved quality and outcomes for surgical cancer care. Finally, given the uncertain future of post-ACA Medicaid expansion under the new administration and current Congress, knowledge on how surgical cancer care will fare with vs without Medicaid expansion will remain highly relevant to policy making.

CONCLUSIONS

Experience from one of the largest pre-ACA Medicaid expansion coverage areas demonstrates that such expansion improves access to surgical cancer care significantly. This pre-ACA expansion, however, did not increase the overall use or change the racial composition of beneficiaries of surgical cancer care. It did, however, shift the financial cost away from patients and hospitals to Medicaid. These results suggest that the ACA’s Medicaid expansion might have similar effects.

Acknowledgments

Support: This study was supported by a grant from the Georgetown-Howard Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science.

Footnotes

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Disclosures outside the scope of this work: Dr DeLeire is a paid consultant to Precision Health Economics, LLC, and receives payment for travel expenses from TerraMedica International Ltd.

Presented at the Southern Surgical Association 128th Annual Meeting, Palm Beach, FL, December 2016.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: Al-Refaie, Zheng, DeLeire, Shara

Acquisition of data: Al-Refaie, Zheng, DeLeire, Shara

Analysis and interpretation of data: Al-Refaie, Zheng, DeLeire, Shara

Drafting of manuscript: Al-Refaie, Zheng, Jindal, Clements, Toye, Johnson, Xiao, Westmoreland, DeLeire, Shara

Critical revision: Al-Refaie, Zheng, DeLeire, Johnson, Shara

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Baltimore, MD: [Accessed November 21, 2016]. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/eligibility/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, et al. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: evidence from the first year. Q J Econ. 2012;127:1057–1106. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjs020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Decker SL. In 2011 nearly one-third of physicians said they would not accept new Medicaid patients, but rising fees may help. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1673–1679. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decker SL. Two-thirds of primary care physicians accepted new Medicaid patients in 2011–12: a baseline to measure future acceptance rates. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1183–1187. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sommers BD, Kronick R. Measuring Medicaid physician participation rates and implications for policy. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2016;41:211–224. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3476117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Refaie WB, Muluneh B, Zhong W, et al. Who receives their complex cancer surgery at low-volume hospitals? J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stitzenberg KB, Meropol NJ. Trends in centralization of cancer surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2824–2831. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aliu O, Auger KA, Sun GH, et al. The effect of pre-Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid eligibility expansion in New York State on access to specialty surgical care. Med Care. 2014;52:790–795. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellimoottil C, Miller S, Ayanian JZ, Miller DC. Effect of insurance expansion on utilization of inpatient surgery. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:829–836. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haider AH, Dankwa-Mullan I, Maragh-Bass AC, et al. Setting a national agenda for surgical disparities research: recommendations from the National Institutes of Health and American College of Surgeons summit. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:554–563. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Millman ML. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Monitoring Access to Personal Health Care Services. Access to Health Care in America. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27:299–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pickup M. Introduction to Time Series Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sommers BD, Baicker K, Epstein AM. Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1025–1034. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1202099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giladi AM, Aliu O, Chung KC. The effect of Medicaid expansion in New York State on use of subspecialty surgical procedures by Medicaid beneficiaries and the uninsured. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:889–897. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanchate AD, Kapoor A, Katz JN, et al. Massachusetts health reform and disparities in joint replacement use: difference in differences study. BMJ. 2015;350:h440. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuckerman S, McFeeters J, Cunningham P, Nichols L. Changes in Medicaid physician fees, 1998–2003: implications for physician participation. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;(Suppl Web Exclusives):W4-374–84. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuckerman S, Williams AF, Stockley KE. Trends in Medicaid physician fees, 2003–2008. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w510–w519. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Health Do. [Accessed December 9, 2016];Medicaid in New York State. Available at: https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/