Abstract

PURPOSE:

To determine the clinical profile, causes and response to corticosteroid therapy in patients admitted and treated for optic neuritis at a tertiary hospital in Cape Town, South Africa.

METHODS:

A retrospective case review of 117 patients with optic neuritis between January 2002 and December 2012. Demographic information, clinical presentation, course of illness, investigations performed and visual outcomes at discharge and at three month follow up were collected for analysis.

RESULTS:

60 of 117 patients (51%) had an identifiable secondary cause for optic neuritis. Of the 57 patients with idiopathic optic neuritis, 14 had features associated with demyelinating disease. HIV and syphilis accounted for 62% of secondary causes of optic neuritis. Presenting visual acuity of hand movements (HM) or worse and absence of pain with extra ocular movement were associated with poorer final visual outcomes in the idiopathic optic neuritis group.

CONCLUSION:

Optic neuritis in our patients, as elsewhere in Africa, tends to be atypical in presentation. A high proportion of patients have an identifiable secondary cause. These patients thus require more extensive investigation in order to identify causes which may influence management. Secondary optic neuritis and idiopathic atypical optic neuritis carry a poorer prognosis than typical demyelinating optic neuritis.

Keywords: Africa, atypical, HIV, optic neuritis

Introduction

Optic neuritis is defined as an inflammatory condition of the optic nerve.[1] The etiology can be divided into demyelinating, infectious, parainfectious, and noninfective inflammatory disorders.[1] The most common cause of optic neuritis worldwide is demyelinating disease, and in countries where multiple sclerosis is common, this accounts for the majority of cases.[1,2,3] In the United States, the incidence of optic neuritis is approximately 5/100 000, which closely follows the incidence of multiple sclerosis.[1,2,3] Optic neuritis is the most commonly unilateral and tends to affect females more than males.[1,2,3] The optic neuritis treatment trial (ONTT) identified those features which had a higher association with the development of multiple sclerosis giving rise to the term “typical optic neuritis.”[4] The features of typical optic neuritis include acute vision loss over 2 weeks with recovery by four to 6 weeks, pain on extraocular movement, age between 15 and 45 years, unilateral involvement, and no other systemic illness to account for the symptoms.[1]

In contrast, African populations tend to have more atypical presentations of optic neuritis and a lower prevalence of multiple sclerosis.[5,6] Limited information is available on the clinical profile, causes, and outcomes of optic neuritis in African populations. We describe the clinical profile, causes, and outcomes of cases admitted to the Groote Schuur Hospital with optic neuritis.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of 117 case records of patients admitted to Groote Schuur Hospital and treated for optic neuritis between January 2002 and December 2012 was conducted. Inclusion criteria were based on clinical findings of acute optic nerve dysfunction with or without optic disc swelling. Acute optic nerve dysfunction was defined by the following clinical signs: visual loss, presence of an afferent pupillary defect, dyschromatopsia (objectively measured using 14 plates of the 2007 edition of the Ishihara test plates), and decreased light brightness appreciation. All patients admitted with acute optic nerve dysfunction were investigated with serological tests, chest X-rays (to help exclude sarcoid and tuberculosis), imaging in the form of a contrasted (CT) scan (followed by magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] if demyelination was suspected), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis if no contraindication to lumbar puncture was present. MRI of the orbit to evaluate for optic nerve enhancement was not routinely performed due to resource availability. Serological tests performed were aimed at excluding systemic conditions known to be associated with optic neuritis, thus an autoimmune screen (rheumatoid factor, ANA, c and P ANCA, anti-dsDNA, and antiphospholipid antibody), serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (S-ACE), HIV serology, serum RPR and fluorescent treponemal antibody (FTA), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and full blood count with differential was conducted. All patients admitted for optic neuritis were treated with systemic steroids in the form of 3 days of intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g daily), followed by 10 days of 1 mg/kg oral prednisone. Demographic information, clinical presentation, course of illness, investigations performed and visual outcomes at discharge and at 3-month follow-up were collected. Patients above the age of 55 years with vascular risk factors (uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and previous history of vascular event), and features highly suggestive of nonarteritic ischemic optic neuropathy (sectoral disc swelling and altitudinal field defect) were automatically excluded based on the ophthalmic emergency care algorithms and criteria for admission, investigation, and treatment of optic neuritis. Patients who had positive serological tests, CSF analysis, or abnormalities of neuroimaging suggestive of a possible secondary cause were labeled as having secondary optic neuritis. Treatment for the secondary cause was instituted as appropriate. Patients who had negative serology, neuroimaging, and CSF analysis were labeled as having idiopathic optic neuritis. The idiopathic group was then subdivided into atypical or typical. Atypical optic neuritis was defined as having any of the following clinical criteria: profound vision loss (worse than count fingers vision), visual loss of 3 or more weeks with no improvement, bilateral involvement, absence of pain, and age >50 years or <12 years. Visual acuity (VA) was measured using Snellen optotypes and then converted to LogMAR using Holladay conversion table.[7] VA measurements of perception of light (PL) and no PL were assigned the arbitrary LogMAR values of 3.5 and 4, respectively, for statistical analysis. The data were collated in an excel spreadsheet and then analyzed using STATA version 10.0 (July 2007, StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). Chi-square and the Wilcoxon–Mann Whitney rank-sum tests were used to test significance of associations in univariate analysis. Logistic regression analysis was also used to test significance in multivariate analysis.

Results

Sixty patients had an identifiable secondary cause of optic neuritis, with 57 patients having idiopathic disease. Fourteen of the 57 patients with idiopathic disease had features of typical optic neuritis, with 43 patients having atypical features.

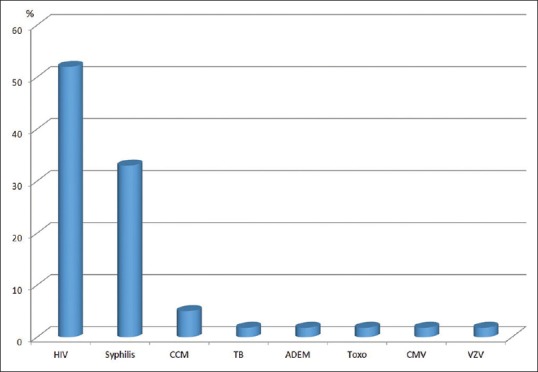

Figure 1 shows the causes of secondary optic neuritis.

Figure 1.

Causes of secondary optic neuritis (CCM = cryptococcal meningitis, TB = tuberculosis, ADEM = acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis, Toxo = toxoplasmosis, CMV = cytomegalovirus, VZV = varicella zoster)

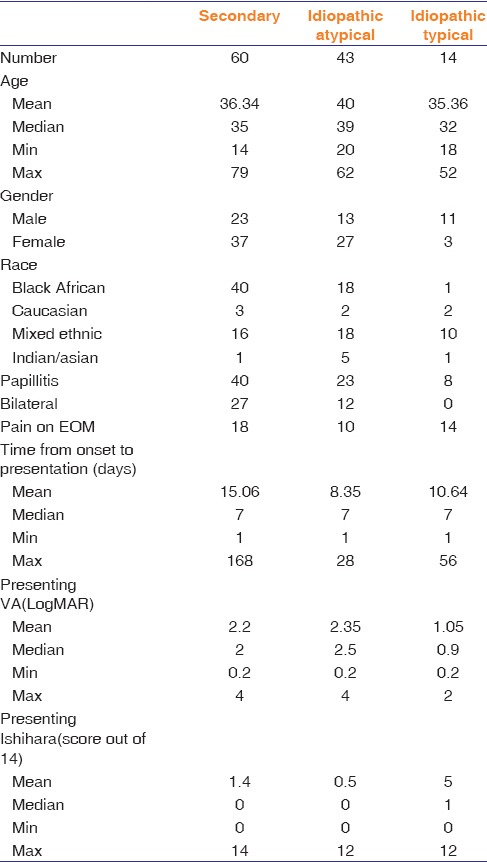

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical profile of secondary and idiopathic optic neuritis.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical profile of secondary and idiopathic optic neuritis

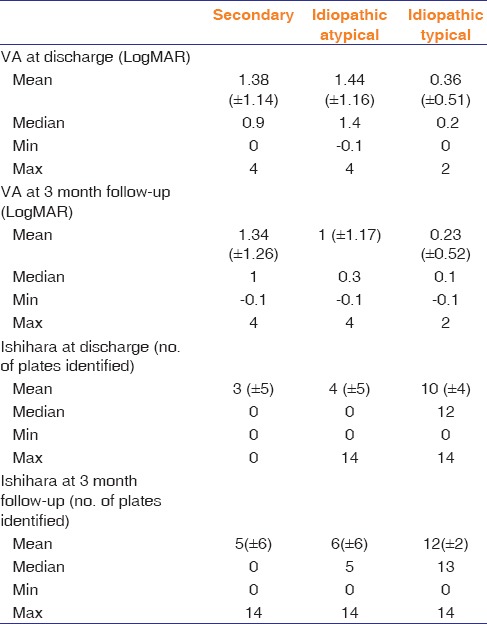

Table 2 shows the outcomes of secondary and idiopathic optic neuritis.

Table 2.

Outcomes of secondary and idiopathic optic neuritis

Patients with secondary optic neuritis and idiopathic atypical optic neuritis with a presenting VA of hand motion (HM) or worse had a poorer outcome at follow-up (mean VA = 1.53 LogMAR vs. 0.81 LogMAR, P = 0.015) compared to patients with better than HM presenting vision in the same group.

There were four cases (4 of 117) in which the CT scan was abnormal. Two had a pituitary tumor, one had a tuberculous granuloma, and one had nonspecific cerebral atrophy. Thirteen of 20 MRI scans (11 performed for patients with typical ON and 2 for idiopathic atypical ON) were abnormal, with the predominant finding being areas of white matter abnormal signal, possibly indicating demyelination. S-ACE, full blood count, and ESR were normal in all cases. The only blood investigations that yielded positive results were the HIV and serum FTA tests. Lumbar puncture was performed in 90 of 117 cases. Seventy of the 90 cases yielded normal CSF findings. The predominant finding in abnormal lumbar punctures was a mild leukocytosis with normal total protein (15 cases). Three cases demonstrated cryptococcal meningitis, one was cytomegalovirus PCR positive and one was varicella zoster PCR positive. In these patients, visual loss from optic nerve inflammation was the presenting feature of their disease.

Of the patients with typical optic neuritis, four patients went on to develop possible multiple sclerosis (three of mixed descent and one Indian), and one Caucasian patient had clinically definite multiple sclerosis. No cases of multiple sclerosis were found in Indigenous African patients.

Discussion

Optic neuritis in the study population differs from that reported in Europe and the United States with the majority of patients either having a secondary cause or having atypical features.

Of the 55 patients with systemic illness, 38 (69%) tested HIV positive. The absence of pain and optic disc swelling are more common features of optic neuritis in the study group. In the idiopathic group, the absence of pain, profound visual loss, and bilateral disease are the main clinical features deviating from the typical features of the ONTT.

Pokroy et al. looked at the clinical profile of cases of idiopathic optic neuritis in black patients and their response to treatment.[6] In contrast to the ONTT, they found that of the 10 patients in their study, the majority had bilateral consecutive or simultaneous disease and 15 out of the 18 eyes had optic disc swelling.[6] Black African patients had a poorer visual prognosis compared to the patients in the ONTT.[6] The review did not look at secondary causes of optic neuritis in black patients. Idiopathic optic neuritis in our study population is predominantly atypical, in keeping with these findings.

Similar findings of atypical optic neuritis are reported in patients of African or African-Caribbean backgrounds.[5] This group of patients had a disproportionately higher representation within the neuromyelitis spectrum of disorders than Caucasian patients in the study population.[5] Several studies have further shown a high incidence of aquaporin-4 antibody (a marker for neuromyelitis optica) among patients with isolated atypical optic neuritis.[5,8,9] Neuromyelitis optica seropositivity was shown to be a predictor of poor outcome.[5,6,7,8,9]

There are several studies which have tried to identify the multiple sclerosis rates in South Africa. Dean reported an incidence of 13/100,000 in English speaking whites with no cases reported in black patients.[10] In a follow-up study in 1994, only six cases of possible multiple sclerosis in black South Africans was found.[11] A study on crude prevalence data in the Kwazulu-Natal province of South Africa found a prevalence of 25.63/100,000 in whites, 0.99/100,000 in blacks, and 1.94/100,000 in people of mixed descent.[12] All of these studies seem to confirm that multiple sclerosis in black and mixed ancestry people is uncommon. Although the study population is small and the time frame not long enough, our study seems to also suggest that demyelinating optic neuritis associated with MS is uncommon in black patients.

The ONTT identified risk factors predicting multiple sclerosis-associated optic neuritis.[4] The identification of these features helped to identify cases in which extensive investigation would prove unhelpful and therefore unnecessary.[2] In our study, 4 of the CT scans performed revealed unusual causes of acute optic nerve dysfunction. Two cases revealed a pituitary adenoma (with compressive optic neuropathy), one tuberculous granuloma, and one generalized cerebral atrophy (thought to be part of advanced HIV disease). Both cases of pituitary adenoma and the tuberculous granuloma showed an initial response to steroid treatment. The cases of pituitary adenoma were referred to neurosurgical services, and antituberculous therapy was initiated in the patient with a tuberculous granuloma. Our study population has a high proportion of secondary and atypical idiopathic optic neuritis, and thus, African patients with optic neuritis require thorough investigation for causes other than demyelinating disease as this may influence treatment.

It is important to note that there can be considerable overlap in the clinical features of NAION and optic neuritis with papillitis.[13,14] Although there are features that are more suggestive of NAION (age >55 years, history of vascular risk factors, sectoral disc swelling, and an altitudinal field defect in keeping with the sectoral disc swelling), there are variations in these features that overlap between the two clinical entities.[13,14] More diffuse disc swelling may be seen in NAION as well as a variation of visual field loss patterns.[14] Furthermore, NAION has been reported in younger patients in the absence of vascular risk factors.[13] In our cohort of patients, cases with features highly suggestive of NAION were excluded from the study; however, it is possible that a cohort of patients with idiopathic ON and papillitis may still represent cases of NAION. Developments in imaging modalities such as optical coherence tomography may help to differentiate between the different causes of disc swelling.[15,16]

The ONTT as well as meta-analyses of 12 randomized control trials revealed that corticosteroid therapy significantly improved short-term VA recovery but had no statistically significant effect on long-term visual outcome.[2,4] Furthermore, the natural course of MS-related optic neuritis is recovery of visual function even without therapy. The clinical experience at Groote Schuur Hospital is that the majority of patients do not fit the typical profile of the ONTT. The HIV epidemic confounds the clinical picture both due to the neurotropic nature of the virus and associated opportunistic infections. Steroid therapy may play a more important role in treating optic nerve inflammation (in combination with the appropriate treatment for identified secondary causes) and preventing permanent visual loss in African patients with optic neuritis, where the multiple sclerosis incidence is low.

All subgroups of optic neuritis in this study showed some improvement in VA with steroid treatment. Gains in VA were most pronounced in the idiopathic typical group, in keeping with demyelinating optic neuritis. Since the prevalence of multiple sclerosis is low in the study population, the optimal route of administration and type of steroid therapy is unclear. A small case series describes the use of steroid for the treatment of optic neuritis in African patients with good clinical response.[17] Studies on the use of dexamethasone in Indian populations have also shown good response to therapy.[18]

Conclusion

Optic neuritis in indigent African populations, with a low prevalence of multiple sclerosis, tends to be atypical in presentation, with a high proportion of patients having an identifiable secondary, most commonly infectious cause. In settings with a high HIV prevalence, HIV and syphilis testing should form part of the routine first-line investigations for patients presenting with optic neuritis. Thorough investigation for possible secondary causes should be undertaken as these may influence management. Secondary optic neuritis and idiopathic atypical optic neuritis carry a poorer prognosis than typical demyelinating optic neuritis. While steroid therapy in secondary and idiopathic atypical optic neuritis has a definite management role, the optimal route, type of steroid, and duration of therapy are unclear. A weakness of our study is that it is a retrospective case note review. A prospective study to assess various regimens of steroid therapy and the role of neuromyelitis optica serology in our patients would be helpful.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hoorbakht H, Bagherkashi F. Optic neuritis, its differential diagnosis and management. Open Ophthalmol J. 2012;6:65–72. doi: 10.2174/1874364101206010065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pau D, Al Zubidi N, Yalamanchili S, Plant GT, Lee AG. Optic neuritis. Eye (Lond) 2011;25:833–42. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shams PN, Plant GT. Optic neuritis: A review. Int MS J. 2009;16:82–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Optic Neuritis Study Group. Multiple sclerosis risk after optic neuritis: Final optic neuritis treatment trial follow-up. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:727–32. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Storoni M, Pittock SJ, Weinshenker BG, Plant GT. Optic neuritis in an ethnically diverse population: Higher risk of atypical cases in patients of African or African-Caribbean heritage. J Neurol Sci. 2012;312:21–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pokroy R, Modi G, Saffer D. Optic neuritis in an urban black African community. Eye (Lond) 2001;15:469–73. doi: 10.1038/eye.2001.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holladay JT. Proper method for calculating average visual acuity. J Refract Surg. 1997;13:388–91. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19970701-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petzold A, Pittock S, Lennon V, Maggiore C, Weinshenker BG, Plant GT, et al. Neuromyelitis optica-IgG (aquaporin-4) autoantibodies in immune mediated optic neuritis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:109–11. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.146894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matiello M, Lennon VA, Jacob A, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Wingerchuk DM, et al. NMO-IgG predicts the outcome of recurrent optic neuritis. Neurology. 2008;70:2197–200. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000303817.82134.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dean G. Annual incidence, prevalence, and mortality of multiple sclerosis in white South-African-born and in white immigrants to South Africa. Br Med J. 1967;2:724–30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5554.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean G, Bhigjee AI, Bill PL, Fritz V, Chikanza IC, Thomas JE, et al. Multiple sclerosis in black South Africans and Zimbabweans. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:1064–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.9.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhigjee AI, Moodley K, Ramkissoon K. Multiple sclerosis in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa: An epidemiological and clinical study. Mult Scler. 2007;13:1095–9. doi: 10.1177/1352458507079274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Behbehani R. Clinical approach to optic neuropathies. Clin Ophthalmol. 2007;1:233–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rizzo JF, 3rd, Lessell S. Optic neuritis and ischemic optic neuropathy. Overlapping clinical profiles. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:1668–72. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080120052024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savini G, Bellusci C, Carbonelli M, Zanini M, Carelli V, Sadun AA, et al. Detection and quantification of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in optic disc edema using stratus OCT. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1111–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.8.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellusci C, Savini G, Carbonelli M, Carelli V, Sadun AA, Barboni P, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: OCT characterization of the acute and resolving phases. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:641–7. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0767-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Omoti AE, Waziri-Erameh MJ. Management of optic neuritis in a developing African country. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2006;13:358–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sethi HS, Menon V, Sharma P, Khokhar S, Tandon R. Visual outcome after intravenous dexamethasone therapy for idiopathic optic neuritis in an Indian population: A clinical case series. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2006;54:177–83. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.27069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]