Abstract

The objective was to describe Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP)-based lifestyle interventions delivered via electronic, mobile, and certain types of telehealth (eHealth) and estimate the magnitude of the effect on weight loss. A systematic review was conducted. PubMed and EMBASE were searched for studies published between January 2003 and February 2016 that met inclusion and exclusion criteria. An overall estimate of the effect on mean percentage weight loss across all the interventions was initially conducted. A stratified meta-analysis was also conducted to determine estimates of the effect across the interventions classified according to whether behavioral support by counselors post-baseline was not provided, provided remotely with communication technology, or face-to-face.

Twenty-two studies met the inclusion/exclusion criteria, in which 26 interventions were evaluated. Samples were primarily white and college educated. Interventions included Web-based applications, mobile phone applications, text messages, DVDs, interactive voice response telephone calls, telehealth video conferencing, and video on-demand programing. Nine interventions were stand-alone, delivered post-baseline exclusively via eHealth. Seventeen interventions included additional behavioral support provided by counselors post-baseline remotely with communication technology or face-to-face. The estimated overall effect on mean percentage weight loss from baseline to up to 15 months of follow-up across all the interventions was −3.98%. The subtotal estimate across the stand-alone eHealth interventions (−3.34%) was less than the estimate across interventions with behavioral support given by a counselor remotely (−4.31%), and the estimate across interventions with behavioral support given by a counselor in-person (−4.65%).

There is promising evidence of the efficacy of DPP-based eHealth interventions on weight loss. Further studies are needed particularly in racially and ethnically diverse populations with limited levels of educational attainment. Future research should also focus on ways to optimize behavioral support.

Keywords: Telemedicine, Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2, Risk Reduction Behavior

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D), accounting for 90 to 95% of all diabetes in the United States (US), has emerged as a dominant public health concern. Estimated to affect 9.3% of the US population, diabetes is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease and stroke, and a primary cause of chronic kidney failure, non-traumatic lower-extremity amputations, and blindness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2014). The costs of diabetes care in the US are unsustainable; yearly diabetes medical expenditures alone have been estimated at $176 billion (CDC, 2014). If no action is taken, demographic and incidence trends suggest that by the year 2050, the proportion of the US adult population with diabetes may more than triple (CDC, 2015). T2D disproportionatly affects certain racial and ethnic minority subpopulations. While the rate of diabetes is 7.6% among non-Hispanic white adults, the rate is 9.0% among Asian American adults, 12.8% among Hispanic adults, and 13.2% among non-Hispanic black adults (CDC, 2014). T2D differentially impacts adults with lower educational attainment. Whereas, the rate of diabetes is 6.5% among adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher, the rate is 9.6% among adults with some college, 10.5% among adults with a high school diploma or GED, and 15.1% among adults with less than a high school diploma (Schiller et al., 2012).

In some cases, T2D can be delayed or prevented, through modification of lifestyle, diet and physical activity, that reduces excess body weight. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) lifestyle intervention demonstrated a 58% decrease in incidence of T2D among overweight adults of diverse race/ethnicity at high-risk of developing T2D. A reduction of body weight over a period of 6 months in the range of 5–7%, was achieved through the DPP lifestyle intervention (Knowler et al., 2002). T2D prevention benefits of the DPP lifestyle intervention have been shown to last up to 10 years (Knowler et al., 2009). Dissemination of DPP-based lifestyle interventions on a large scale in the US has not yet been achieved. One limiting factor to widespread dissemination is cost. The lifestyle intervention in the DPP, was estimated to cost $1,399 per participant, over the first year (Hernan et al., 2003).

Modifications that are often proposed to decrease cost and increase scalability of DPP-based lifestyle interventions include delivery of interventions in churches (Boltri et al., 2008), workplaces (Aldana et al., 2006), and other community-based settings (e.g. YMCA) (Ackermann et al., 2008). Modification for delivery via different electronic health approaches (eHealth) is also advocated (Atienza and Patrick, 2011; Green et al., 2012; Ockene et al., 2011; Wolfenden et al., 2010). The efficacy of DPP-based lifestyle interventions modified to the local context or modified for delivery via eHealth has been evaluated in several systematic reviews with and without meta-analysis (Ali et al., 2012; Whittemore, 2011). While these reviews have included DPP-based eHealth interventions, conclusions about the efficacy on weight loss of DPP-based eHealth interventions were limited by the broad inclusion criteria of the reviews and the small number of eHealth interventions that were available at the time. A systematic review of 16 DPP-based interventions by Whittemore (2011) included only one eHealth intervention, and a systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 DPP-based interventions by Ali and colleagues (2012) included only four eHealth interventions. In the meta-analysis, a subtotal estimate across four eHealth interventions of the effect on mean percentage weight loss was 4.20% (Ali et al., 2012).

A factor that was not accounted for in the previous reviews is the provision of behavioral support in eHealth interventions by a counselor, either remotely with communication technology or through face-to-face encounters. Provision of behavioral support by a counselor in eHealth interventions is considered a factor to promote adherence (Ritterband et al., 2009), and a primary driver of cost (Tate et al., 2009). Given the implications of the scalability of DPP-based eHealth interventions, the rapid evolution of eHealth research, and the importance of systematically evaluating behavioral support provided in eHealth interventions, an updated review solely of DPP-based eHealth interventions in which provision of behavioral support is explored is warranted.

Therefore, the aims of this systematic review were to: 1) describe DPP-based eHealth interventions, 2) describe the characteristics of the DPP-based eHealth intervention samples, 3) estimate the overall effect across all the DPP-based eHealth interventions on weight loss, 4) estimate subtotal effects across the DPP-based eHealth interventions stratified by behavioral support on weight loss.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2010). Inclusion criteria were: 1) randomized controlled trials or cohort studies with or without a control group that evaluated the effect of an intervention on weight loss; 2) intervention based on the DPP lifestyle intervention curriculum delivered via eHealth approaches [web-based/Internet-based applications, social media, serious games, DVDs, mobile applications, and certain computer-based telehealth applications (e.g. interactive voice response, videoconferencing) as defined by Eysenbach and the CONSORT-EHEALTH Group (2011)]; 3) participants ≥18 years of age residing in the US; and 4) study results published in English in a peer-reviewed article.

Search, Study Selection, and Data Collection Processes

The online databases Medline and EMBASE were searched to identify records published from January 1, 2003 to February 29, 2016 that met the inclusion criteria. This start date of the search was selected to include translations of the DPP lifestyle intervention, the results of which were published in February, 2002 (Knowler et al., 2002). The search strategy was developed with the collaboration of a professional librarian (GW). A full description of the electronic search strategy for Medline, from which the search of the EMBASE database was modeled, is available in the appendices (Appendix A). After duplicates were removed, one reviewer (KJ) screened the record titles and abstracts to identify records that met the search criteria. Reference lists and review articles were checked for relevant articles. Full-text articles were retrieved and assessed by one reviewer (KJ). Questions about whether an article should be included were resolved through discussion with a second reviewer (RW) and decisions were made by consensus.

Data extracted from the articles, included sample characteristics, intervention characteristics, and weight loss outcomes. Only data provided numerically in the articles and/or supplementary materials was extracted; data was not read off graphs. When studies did not report mean percentage weight loss, calculations were carried out using the data available. We attempted to contact authors by email if insufficient data was reported in the article to estimate size of the effect of the intervention on weight loss. One reviewer (KJ) extracted and coded data from all of the studies that met the inclusion criteria. To check for errors in the extraction and coding process, a second reviewer (SN) independently extracted data from a randomly selected subset of studies (45 percent).

Risk of Bias Assessment

A risk of bias assessment of individual studies was made using a methodological quality assessment tool appropriate for randomized controlled trials and cohort studies with or without a comparison group (Bennett et al., 2014). This assessment assigns a methodological quality score by tallying points for 10 items (range 0–10). Two reviewers (KJ and SN) independently assessed the methodological quality of each study. Any differences were resolved through discussion and consensus. This information was used in a sensitivity analysis to evaluate whether the results and conclusions of the review were affected by the decision to include studies of lower methodological quality. For the purpose of the sensitivity analysis, studies with scores of 5 or less were considered to be lower methodological quality and those with scores of 6 or more were considered to be higher methodological quality.

Statistical analyses

In order to evaluate the characteristics of participants of DPP-based eHealth interventions, comparisons were made between characteristics of the participants in the included studies of this review and characteristics of the participants in the DPP clinical trial sample (Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group, 2000; Knowler et al., 2002).

Interventions were initially classified as to whether they included face-to-face baseline orientations. Interventions were then sorted on the basis of the provision of behavioral support by a counselor post-baseline into three subtypes: stand-alone interventions, interventions supported remotely with communication technology, and interventions supported through face-to-face contacts. Interventions were classified as stand-alone when behavioral support by a counselor post-baseline was not offered in the intervention. Interventions were classified as supported remotely in cases in which behavioral support by a counselor post-baseline was offered during the course of the intervention only via one or more modes of distance-based communication technology (eg. online messaging communications, personalized emails, text messaging, and telephone calls). Interventions were classified as supported face-to-face in cases in which behavioral support was offered in face-to-face meetings throughout the course of the intervention.

A meta-analysis stratified by these three subtypes of behavioral support was conducted that led to an overall estimate across all of the DPP-based eHealth interventions of the effect on mean percentage weight change, and subtotal estimates across the three subtypes of behavioral support. The primary outcome measure was mean percentage weight change of participants in the intervention arm from baseline to the last available follow-up (up to 15 months) following the intervention. An inverse-variance weighted random-effects (DerSimonian and Laird) meta-analysis was used, which allows for estimation of a summary effect when attributes of included cases differ in aspects, including subject samples, study designs, and intervention characteristics (Cooper et al., 2009). To evaluate the inconsistency in the effect size estimates, the homogeneity index, Higgins’ I2, was calculated. Following general guidelines, values of I2, 0% to 40%, 30% to 60%, 50% to 90%, were interpreted respectfully as minimal heterogeneity, moderate heterogeneity, and substantial heterogeneity (Higgins JPT, 2011).

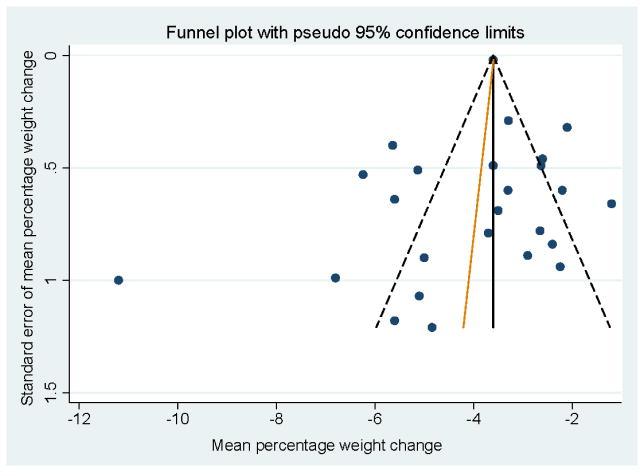

In a sensitivity analysis undertaken to evaluate whether the meta-analysis results were robust to the decision to include studies of differing methodological quality, a subsequent meta-analysis was conducted across a subset of the DPP-based eHealth interventions that would have been eligible under more stringent methodological quality eligibility criteria (i.e. study methodological quality score ≥ 6/10). Comparisons were then made between the estimates of the two meta-analyses, the meta-analysis that included the interventions from all of the studies and the meta-analysis that included only the interventions from the studies with methodological quality scores ≥ 6/10. To evaluate the potential for publication bias which can lead to overestimation of the estimates of the interventions effects (Higgins JPT, 2011), a funnel plot was visually inspected, and Egger’s test was used (Higgins JPT, 2011). Analyses were performed using published macros (metan, metabias, and metafunnel) in Stata 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Search results

Figure 1 illustrates the study search and selection process (Moher et al., 2010). The initial search yielded 3,294 unique records. After excluding 556 duplicate records, and 2,738 records on the basis of screening of titles and abstracts, 86 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Twenty-two studies from 21 articles met all the inclusion and exclusion eligibility criteria in the qualitative review (one article reported on 2 studies). Included in the meta-analysis were 21 of the 22 studies (sufficient data on weight loss was not reported for the intervention in one study: (Vadheim et al., 2010)).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of literature search and selection process

* Categories are mutually exclusive

Abbreviations: DPP-Diabetes Prevention Program

Studies

Among the 22 studies, the majority were randomized controlled trials (n=13) (Ackermann et al., 2014; Azar et al., 2015; Bennett et al., 2010; Block et al., 2015; Estabrooks and Smith-Ray, 2008; Fischer et al., 2016; Fukuoka et al., 2015; Leahey et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2013; Tate et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 2015; Wing et al., 2010). Other study designs were single group intervention studies (n=5) (McTigue et al., 2009; Pagoto et al., 2015; Sepah et al., 2014; Skoyen et al., 2015; Thomas and Wing, 2013), non-randomized controlled trials (n=2) (Kramer et al., 2010; Vadheim et al., 2010), a comparative effectiveness trial (n=1) (Piatt et al., 2013), and a retrospective cohort study (n=1) (Ahrendt et al., 2014). Mean length of study follow-up was 3.8 months and ranged from 3 to 15 months. Mean attrition was 18% and ranged from 6% to 53%. Intervention effect on mean percentage weight loss was analyzed using intention-to-treat analyses or last-observation-carried-forward (n=21), or per-protocol analyses (n=1). The methodological quality ratings ranged from 3 to 9 on a scale of 0 to 10. Thirteen of the studies were scored as ≥ 6/10 on the methodological quality scale, indicating that they had a lower risk of bias (Tate et al., 2003; Estabrooks and Smith-Ray, 2008; McTigue et al., 2009; Bennett et al., 2010; Wing et al., 2010 (study1&2); Ma et al., 2013; Ackermann et al., 2014; Leahey et al., 2014; Block et al., 2015; Fukuoka et al., 2015; Thomas et al., 2015; Fischer et al., 2016). Details of the methodological quality scoring available upon request.

Participants

Two thousand ninety seven participants were enrolled in the DPP-based eHealth intervention groups in the 22 studies. Samples per intervention group ranged from 12 to 220 participants (Table 1). Eligible individuals were recruited through the health system and clinics (n=12) (Ahrendt et al., 2014; Azar et al., 2015; Bennett et al., 2010; Block et al., 2015; Estabrooks and Smith-Ray, 2008; Fischer et al., 2016; Kramer et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2013; McTigue et al., 2009; Skoyen et al., 2015; Thomas and Wing, 2013; Thomas et al., 2015), advertisements in local communities (eg. TV, radio, newspaper) (n=6) (Ackermann et al., 2014; Fukuoka et al., 2015; Pagoto et al., 2015; Piatt et al., 2013; Tate et al., 2003; Vadheim et al., 2010), a statewide wellness program (n=3) (Leahey et al., 2014; Wing et al., 2010), and online (n=1) (Sepah et al., 2014).

Table 1.

Characteristics of DPP-based eHealth interventions included in review in subgroups by extent participants were offered behavioral support by a counselora

| Author (year) State |

Enrollment channel and setting | Sample (Intervention arm only) | Study design and analysis method | Drop out (%) | Length of follow-up | Intervention | Components promoting interaction | Quality Scorea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stand-alone | ||||||||

|

Tate et. al., 2003 b (Program without e-counseling) RI |

Local community and research center | n=46 Female: 89% Age: 47.3±9.5 yrs BMI: 33.7±3.7 kg/m2 Non-White: 11% ≥ Some college: 85% ≥ College degree: 48% |

RCT/ITT | 15.2 | 12 mo | Web-based application Media format: text Core: tutorials updated weekly for 1 month Maintenance: tutorials updated weekly for 11 months Counselor support Baseline: 1-hour face-to-face group Post-baseline: NR Personnel: Staff with degrees in health education, nutrition or psychology |

NR | 8 |

|

Estabrooks and Smith-Ray, 2008 CO |

Health system in urban/suburban area | n=39 Female: 71.8% Age: 57.8 yrs BMI: NR Non-White: 31% ≥ Some college: 51% ≥ College degree: NR |

RCT/ITT | 28.2 | 3 mo | IVR calls Media format: audio Core: weekly IVR calls for 3 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: 90 min face-to-face group Post-baseline: NR Personnel: NR |

NR | 7 |

|

Wing et. al., 2010 (Study 1) RI |

Shape Up RI (Statewide lifestyle program) | n=89 Female: 83.2% Age: 46.5±10.1 yrs BMI: 33.8±6.3 kg/m2 Non-White: 12.3% ≥ Some college: NR ≥ College degree: 69% |

RCT/ITT | 7.8 | 3 mo | Web-based application Media format: video (animated PowerPoint) Core: 12 lessons/3 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: NR Post-baseline: NR Personnel: NR |

Pedometer + team competition | 7 |

|

Wing et. al., 2010 (Study 2) RI |

Shape Up RI (Statewide lifestyle program) | n=82 Female: 89.8% Age: 46.9±9.7 yrs BMI: 33.9±5.6 kg/m2 Non-White: 11.7% ≥ Some college: NR ≥ College degree: 63% |

RCT/ITT | 9.8 | 3 mo | Web-based application Media format: video (animated PowerPoint) Core: 12 lessons/3 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: face-to-face group Post-baseline: NR Personnel: study staff |

Pedometer + team competition | 8 |

|

Ma et. al., 2013 CA |

Primary care clinic suburban community | n=81 Female: 45.7% Age: 51.8±9.9 yrs BMI: 31.7±4.7 kg/m2 Non-White: 21% ≥ Some college: 100% ≥ College degree: NR |

RCT/ITT | 21 | 15 mo | DVDs (Group Lifestyle Balance sessions) Media format: video Core: 12 sessions on DVD/3 months Maintenance: 12 months Counselor support Baseline: face-to-face group session Post-baseline: NR Personnel: study staff |

Pedometer + scale | 9 |

|

Ackermann et. al., 2014 b (Program without online tools) PA and TN |

2 urban communities | n=155 Female: 80% Age: 46.5±11.3 yrs BMI: 36.1±6.0 kg/m2 Non-White: 23% ≥ Some college: 92% ≥ College degree: 28% |

RCT/ITT | 13 | 5 mo | Video On-Demand Media format: video vignette + automated phone calls Core: 16 episodes/4–5 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: NR Post-baseline: NR Personnel: NA |

Scale (cellular enabled) | 8 |

|

Leahey et. al., 2014 b (Standard program) RI |

Shape Up RI (Statewide lifestyle program) | n=90 Female: 82.2% Age: 46.2±SE 1.2 yrs BMI: 34.7±SE 0.7 kg/m2 Non-White: 10% ≥ Some college: 97% ≥ College degree: NR |

RCT/ITT | NR | 12 mo | Web-based application Media format: text Core: 12 sessions/3 month Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: 1-hour face-to-face group Post-baseline: NR Personnel: Staff with master’s degree level training in behavioral health |

Pedometer + social media platform + teams challenges + access to community workshops | 7 |

|

Block et. al., 2015 CA |

Health system in suburban area | n=163 Female: 31.9% Age: 55.0±8.8 yrs BMI: 31.1±4.5 kg/m2 Non-White: 33.1% ≥ Some college: 84% ≥ College degree: NR |

RCT/ITT | NR | 6 mo | Web-based application + mobile phone app Media format: text Core: 24 sessions/6 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: face-to-face orientation Post-baseline: NR Personnel: NA |

Virtual teams (Point system with rewards) + peer-to-peer messaging | 8 |

|

Thomas et. al., 2015 RI |

Medical practice in urban area | n=77 Female: 80.5% Age: 52.8±10.2 yrs BMI: 34.9±4.6 kg/m2 Non-White: 9.1% ≥ Some college: 94% ≥ College degree: 58% |

RCT/ITT | 20.8 | 6 mo | Web-based application + mobile phone app Media format: video + audio + animation Core: 12 sessions/3 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: 1 hour face-to-face group Post-baseline: NR Personnel: NR |

NR | 9 |

| Supported remotely | ||||||||

|

Tate et. al., 2003 a (Program with e-counseling) RI |

Local community and research center | n=46 Female: 91% Age: 49.8±9.3 yrs BMI: 32.5±3.8 kg/m2 Non-White: 11% ≥ Some college: 85% ≥ College degree: 52% |

RCT/ITT | 17.4 | 12 mo | Web-based application Media format: text Core: tutorials updated weekly for 1 month Maintenance: tutorials updated weekly for 11 months Counselor support Baseline: 1 hour face-to-face group Post-baseline: email Personnel: Degree in health education, nutrition, or psychology |

NR | 8 |

|

McTigue et. al., 2009 PA |

Internal medicine practice | n=50 Female: 76% Age: 51.94±10.82 yrs BMI: 36.43±6.78 kg/m2 Non-White: 14% ≥ Some college: 96% ≥ College degree: 68% |

Single group intervention study | 10 | 12 mo | Web-based application Media format: audio-narrated lessons Core: 16 lessons/4 months Maintenance: 8 lessons/8 months Counselor support Baseline: 2-hour face-to-face group Post-baseline: online messaging + chatroom Personnel: Nurse educator |

Pedometer | 6 |

|

Kramer et. al., 2010 CA |

Primary care practice in rural community | n=22 Female: 71% Age: 59.7 yrs BMI: 32.85±6.14 kg/m2 Non-White: 17% ≥ Some college: 86% ≥ College degree: NR |

Non-randomized controlled trial/ITT-LOCF | 36.4 | 3 mo | DVDs (Group Life Balance videos) Media format: video Core: 12 sessions/3 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: 1 face-to-face session Post-baseline: telephone calls Personnel: Health care professionals |

Pedometer | 4 |

|

Piatt et. al., 2013 a (Internet program) PA |

8 communities in rural region | n=101 Female: 88.1% Age: 48.7±9.7 yrs BMI: 36.1±6.4 kg/m2 Non-White: 0.9% ≥ Some college: 81% ≥ College degree: 31% |

Comparative effectiveness trial/ITT | 56.4 | 3 mo | Web-based application (Group Life Balance videos) Media formant: video Core: 12 sessions/3–4 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: 1 group session Post-baseline: online messaging Personnel: preventionist + lay health coaches |

Pedometer | 5 |

|

Ackermann et. al., 2014 a (Program with online tools) PA and TN |

2 urban communities | n=159 Female: 85% Age: 46.9±11.3 yrs BMI: 35.1±5.7 kg/m2 Non-White: 23% ≥ Some college: 82% ≥ College degree: 29% |

RCT/ITT | 20 | 5 mo | Video-on-demand + web-based application Media format: video vignette + automated phone calls Core: 16 episodes/4–5 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: NR Post-baseline: email + online forum Personnel: virtual coach |

Scale (cellular enabled) + peer-to-peer platform | 8 |

|

Ahrendt et. al., 2014 SD |

VA Health system | n=60 Female: 8% Age: 57±10.1 yrs BMI: 38.9±7.3 kg/m2 Non-White: 28% ≥ Some college: NR ≥ College degree: NR |

Retrospective cohort study | NA | 12 mo | Web-based videoconferencing Media format: live video conference Core: 12 sessions/3 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: face-to-face orientation Post-baseline: group-based video conferencing Personnel: registered dietitians, psychologist, physical therapist, wellness nurse |

NR | 4 |

|

Sepah et. al., 2014 NR |

Online | n=220 Female: 82.7% Age: 43.6±12.4 yrs BMI: 36.6±7.5 kg/m2 Non-White: 49.8% ≥ Some college: NR ≥ College degree: 52% |

Single group intervention study/ITT | 26.4 | 12 mo | Web-based application Media format: text Core: 16 sessions/4 months Maintenance: 9 sessions/8 months Counselor support Baseline: NR Post-baseline: online messages and/or phone calls Personnel: professional health coach |

Pedometer + scale (wireless) + photo frame and other kits + peer-to-peer platform | 3 |

|

Azar et. al., 2015 CA |

Medical practice in suburban region | n=32 Female: 0% Age: 47.2±7.9 yrs BMI: 34.6±2.8 kg/m2 Non-White: 25.8% ≥ Some college: NR ≥ College degree: 72% |

RCT/ITT | 25 | 3 mo | Web-based videoconferencing Media format: live video conference Core: 12 sessions/3 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: face-to-face orientation Post-baseline: online video conferencing Personnel: trained facilitator |

Scale (Wi-Fi “smart scale”) + web camera for use during study (high definition with built in microphone) | 5 |

|

Skoyen et. al., 2015 CA |

VA Health system in urban area | n=171 Female: 21.6% Age: 51.0 yrs BMI: 38.6 kg/m2 Non-White: 37.4% ≥ Some college: NR ≥ College degree: NR |

Single group intervention study/NA | 28.1 | 3 mo | Telehealth monitor Media format: text + video Core: daily/3 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: face-to-face orientation Post-baseline: email Personnel: care coordinator |

Pedometer + Scale (Wi-Fi enabled) + telehealth monitor (for use during study) | 4 |

| Supported face-to-face | ||||||||

|

Bennett et. al., 2010 MA |

Single internal medicine department in urban area | n=51 Female: 41.2% Age: 54.4±7.4 yrs BMI: 35.0±3.5 kg/m2 Non-White: 54.9% ≥ Some college: NR ≥ College degree: 56% |

RCT/ITT | 14 | 3 mo | Web-based application Media format: text Core: material updated biweekly/3 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: 20 min face-to-face session Post-baseline: 20 min face-to-face session + 2 phone calls + online messaging Personnel: Registered Dietitian |

2 raffles of $50 gift certificates | 8 |

|

Vadheim et. al., 2010 MT |

2 rural communities | n=16 Female: 93% Age: 50±7 yrs BMI: 38.7±8 kg/m2 Non-White: NR ≥ Some college: NR ≥ College degree: NR |

Non-randomized controlld trial | 12 | 4 mo | Telehealth video conferencing Media format: live video conference Core: 16 sessions/4 months Maintenance: 6 sessions/6 months Counselor support Baseline: intake visit face-to-face Post-baseline: group-based video conferencing + physical activity guidance face-to-face Personnel: Registered dietitian, trained coach + local recreation center staff |

Supervised activity sessions at local recreation center | 4 |

|

Piatt et. al., 2013 b (DVD program) PA |

8 communities in rural region | n=113 Female: 85% Age: 52.4±10.9 yrs BMI: 36.2±7.2 kg/m2 Non-White: 6.2% ≥ Some college: 78% ≥ College degree: 33% |

Comparative effectiveness trial/ITT | 43.4 | 3 mo | DVDs (Group Lifestyle Balance videos) Media format: video Core: 12 sessions/3–4 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: screening face-to-face Post-baseline: 4 group sessions + telephone calls Personnel: trained coach |

Pedometer | 5 |

|

Thomas and Wing, 2013 RI |

Web site of research center | n=20 Female: 95% Age: 53.0±SE 1.9 yrs BMI: 36.3±SE 1.2 kg/m2 Non-White: 15% ≥ Some college: 85% ≥ College degree: 60% |

Single group intervention study | 10 | 6 mo | Web-based application + mobile phone application Media format: text + video Core: 15 sessions/3 months Maintenance: 3 months Counselor support Baseline: 1-hour face-to-face orientation Post-baseline: 12 face-to-face sessions individually + online messages to smartphone Personnel: study staff |

iPhone (for use during study) | 5 |

|

Leahey et. al., 2014 a (Enhanced internet program) RI |

Shape Up RI (Statewide lifestyle program) | n=94 Female: 86.2% Age: 47.7±SE 1.1 yrs BMI: 33.4±SE 0.7 kg/m2 Non-White: 18.1% ≥ Some college: 88% ≥ College degree: NR |

RCT/ITT | NR | 12 mo | Web-based application Media format: text Core: 12 sessions/3 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: 1-hour face-to-face group Post-baseline: 12 face-to-face group sessions Personnel: master’s level staff with training in behavioral health |

Pedometer + Social media platform + teams challenges + access to community workshops | 7 |

|

Fukuoka et. al., 2015 CA |

Local urban community | n=30 Female: 76.7% Age: 57.1±9.1 yrs BMI: 32.2±5.6 kg/m2 Non-White: 56.7% ≥ Some college: NR ≥ College degree: NR |

RCT/ITT | 7 | 5 mo | Mobile phone application Media format: text + video Core: daily messages/5 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: 1 face-to-face session Post-baseline: 6 face-to-face sessions individually Personnel: trained non-medical staff |

Pedometer + iPhone (for use during study) | 8 |

|

Pagoto et. al., 2015 RI |

Local community & medical school | n=12 Female: 92% Age: 45.8±9.6 yrs BMI: 34.1±3.6 kg/m2 Non-White: 25% ≥ Some college: NR ≥ College degree: NR |

Single group intervention study | 17 | 3 mo | Web-based application (Twitter) Media format: text Core: daily posts/3 months Maintenance: NR Counselor support Baseline: 1 face-to-face session Post-baseline: 1 face-to-face group session Personnel: trained coach |

Peer-to-peer platform | 5 |

|

Fischer et. al., 2016 CO |

Federally qualified health center | n=78 Female: 70.5% Age: 47.7±12.4 yrs BMI: NR Non-White: NR ≥ Some college: NR ≥ College degree: NR |

RCT/ITT | 7.7 | 12 mo | Text messages Media format: text Core and maintenance: 6 messages each week/12 months) Counselor support Baseline: face-to-face enrollment meeting Post-baseline: Optional group classes + individual appointments (in-person or by phone) Personnel: Nutritionist or nurse |

NR | 7 |

Abbreviations:

SD = standard deviation; yrs = years; BMI = body mass index; RCT = randomized controlled trial; ITT = Intent to treat; mo = months; LOCF = last-observation carried forward

Quality scores assigned using a quality assessment tool appropriate for randomized controlled trials and other intervention efficacy trial designs. This method assigns a quality score by tallying points for 10 items (range 0–10).

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants in the intervention arms that received the DPP-based eHealth interventions along with the characteristics of the sample of the original DPP trial are displayed in Table 2. Compared to the benchmark of the participant sample in the original DPP trial, the majority of the participant samples of the DPP-based eHealth interventions had a higher mean BMI, had less racial/ethnic diversity, and had higher educational attainment. Participants were predominantly female (mean 70%; range 0% to 95%) and adults belonging to ethnic/racial minority populations were underrepresented (mean 23%; range 1% to 57%). Among studies that reported educational attainment, a relatively high proportion of participants reported completing some college or more (mean 85%; range 51% to 100%).

Table 2.

Comparison of original DPP sample and DPP-based eHealth intervention samples

| Original DPP | DPP-based eHealth interventions Mean±SD/ (range) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Stand-alone | Supported remotely | Supported face-to-face | ||

| Sample size | n=1079 | n=2097 (12–220) | n=822 (39–163) | n=861 (22–220) | n=414 (12–113) |

| BMI | 33.9 kg/m2 | 34.9±2.0 kg/m2 (31.1–38.9) | 33.7±1.6 kg/m2 (31.1–38.6) | 35.7±2.2 kg/m2 (32.5–38.9) | 35.1±3.0 kg/m2 (32.2–38.7) |

| Age | 51 yrs | 51±4 yrs (44–60 yrs) | 50±4 yrs (41–58 yrs) | 51±5 yrs (44–60 yrs) | 51±4 yrs (51–57 yrs) |

| Female | 68% | 70±27% (0–95%) | 73±20% (46–90%) | 58±37% (0–91%) | 80±18% (41–95%) |

| Diversity (non-White) | 46% | 23±15% (1–57%) | 18±9% (10–33%) | 23±15% (1–50%) | 29±21% (6–57%) |

| Education (≥ some college) | 74% | 85±12% (51–100%) | 86±17% (51–100%) | 86±6% (81–96%) | 84±5% (78–88%) |

Abbreviations:

DPP = the Diabetes Prevention Program, SD = standard deviation, BMI = body mass index, yrs = years

Interventions

In the 22 studies, 26 different DPP-based eHealth interventions were evaluated (Table 1). To deliver DPP content, a variety of eHealth approaches were employed. Web-based applications were used in more than half of the interventions (n=12) (Bennett et al., 2010; Leahey et al., 2014; McTigue et al., 2009; Pagoto et al., 2015; Piatt et al., 2013; Sepah et al., 2014; Tate et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 2015; Wing et al., 2010). In two cases, web-based interactive videoconferencing technology was used (Ahrendt et al., 2014; Azar et al., 2015). Interventions delivered via mobile phone used a variety of approaches including, interactive voice response automated telephone calls (n=1) (Estabrooks and Smith-Ray, 2008), short message service (SMS) text messaging (n=1) (Fischer et al., 2016), and a mobile phone application (n=1) (Fukuoka et al., 2015). A web-based application and a mobile phone application was used in two interventions (Thomas and Wing, 2013; Block et al., 2015). Telehealth technologies used, included a videoconferencing system (n=1) (Vadheim et al., 2010), and a telehealth monitor (a phone-sized device with a screen, several buttons and a speaker that is connected to a telephone landline in the participant’s home; n=1) (Skoyen et al., 2015). A number of interventions used DVDs (n=3) (Kramer et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2013; Piatt et al., 2013). Interventions delivered via television used video on-demand television programing (n=1) (Ackermann et al., 2014), or a combination of video on-demand television programing and a web-based application (n=1) (Ackermann et al., 2014).

Content was presented in a range of media formats, including text (n=7) (Bennett et al., 2010; Block et al., 2015; Fischer et al., 2016; Pagoto et al., 2015; Sepah et al., 2014; Tate et al., 2003), text and audio (audio-narrated PowerPoint presentations; n=1) (McTigue et al., 2009), text and video (n=3) (Fukuoka et al., 2015; Skoyen et al., 2015; Thomas and Wing, 2013), audio (n=1) (Estabrooks and Smith-Ray, 2008), video (n=2) (Wing et al., 2010), video (Group Lifestyle Balance videos of pre-recorded staged group meetings with professional actors portraying interventionists and participants; n=4) (Kramer et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2013; Piatt et al., 2013), audio and video vignette (chronicles of experiences of a group of participants in a reality TV format; n=2) (Ackermann et al., 2014), live video conference (n=3) (Ahrendt et al., 2014; Azar et al., 2015; Vadheim et al., 2010), and multimedia (n=3) (Leahey et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2015).

Behavioral Support

Among the 26 DPP-based eHealth interventions, 22 interventions included face-to-face contact at baseline. In cases in which a face-to-face baseline orientation session was offered, topics included orientation to the use of the eHealth application employed in the intervention, introduction of dietary intake and physical activity goals, and/or provision of supplemental curricular content. There were only four cases of DPP-based eHealth interventions in which a face-to-face baseline orientation session was not offered (Ackermann et al., 2014; Sepah et al., 2014; Wing et al., 2010).

Nine of the 26 eHealth DPP-based eHealth interventions were stand-alone interventions in which no behavioral support by a counselor post-baseline was offered (Ackermann et al., 2014; Block et al., 2015; Estabrooks and Smith-Ray, 2008; Leahey et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2013; Tate et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 2015; Wing et al., 2010). Nine interventions offered behavioral support by a counselor post-baseline delivered remotely (Ackermann et al., 2014; Ahrendt et al., 2014; Azar et al., 2015; Kramer et al., 2010; McTigue et al., 2009; Piatt et al., 2013; Sepah et al., 2014; Skoyen et al., 2015; Tate et al., 2003). Behavioral support offered remotely by counselors included videoconferencing (n=2) (Ahrendt et al., 2014; Azar et al., 2015), personalized e-mail messages (n=3) (Ackermann et al., 2014; Skoyen et al., 2015; Tate et al., 2003), online messaging (n=2) (McTigue et al., 2009; Piatt et al., 2013), telephone sessions (n=1) (Kramer et al., 2010), or multiple modes (online messaging and telephone sessions) (n=1) (Sepah et al., 2014). In 8 of the 26 interventions, participants were offered behavioral support in face-to-face meetings with counselors throughout the course of the treatment, either individually (n=3) (Bennett et al., 2010; Fukuoka et al., 2015; Thomas and Wing, 2013), or as a member of a group (n=5) (Fischer et al., 2016; Leahey et al., 2014; Pagoto et al., 2015; Piatt et al., 2013; Vadheim et al., 2010).

Incentives

A number of different incentives were used to improve retention and promote interaction, including raffles of gift certificates (n=1) (Bennett et al., 2010), iPhone to use during the study (n=2) (Fukuoka et al., 2015; Thomas and Wing, 2013), pedometers (n=12) (Fukuoka et al., 2015; Kramer et al., 2010; Leahey et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2013; McTigue et al., 2009; Piatt et al., 2013; Sepah et al., 2014; Skoyen et al., 2015; Wing et al., 2010), standard weight scales (n=1) (Ma et al., 2013), weight scales that automatically transmitted body weight cellularly (n=5) (Ackermann et al., 2014; Azar et al., 2015; Sepah et al., 2014; Skoyen et al., 2015), and access to community workshops (n=2) (Leahey et al., 2014).

Effect of interventions on weight loss

The results of the meta-analysis are presented in Figure 2. The overall estimate across all the DPP-based eHealth interventions of the effect on mean percentage weight change was −3.98% (95% confidence interval of −4.49 to −3.46; I2=88.2%). When results were stratified by behavioral support (stand-alone, supported remotely, and supported face-to-face), the subtotal estimate across the 9 stand-alone interventions was −3.34% (95% confidence interval of −4.00 to −2.68: I2=82.4%), the subtotal estimate across the 9 interventions with remote behavioral support was −4.31% (95% confidence interval of −5.26 to −3.37; I2= 78.4%), and the subtotal estimate across the 7 interventions with face-to-face behavioral support was −4.65% (95% confidence interval of −6.63 to −2.67; I2=94.5%).

Figure 2.

Forest plot displaying the overall random-effects estimate and the subtotal estimate stratified by behavioral support of the inverse-variance weighted random-effects (DerSimonian and Laird) meta-analysis of the effect of Diabetes Prevention Program based eHealth interventions on mean percentage weight change

In the sensitivity analysis limiting inclusion in the meta-analysis to only the 16 interventions tested in the 13 studies with a methodological quality score ≥ 6/10, the estimate of the effect on mean percentage weight change was −3.40% (95% confidence interval of −3.94% to −2.85%; I2=80.7) (Table 3). When results were stratified by behavioral support, the subtotal estimate across the 9 stand-alone interventions with a methodological quality score ≥6/10 was −3.34% (95% confidence interval of −4.00% to −2.68%; I2=82.4), the subtotal estimate across the 3 interventions with remote behavioral support with a methodological quality score ≥ 6/10 was −4.14% (95% confidence interval of −5.60% to −2.67%; I2=34.6%), and subtotal estimate across the 4 interventions with face-to-face behavioral support with a methodological quality score ≥ 6/10 was −3.33% (95% confidence interval of −5.07% to −1.59%; I2=87.0%). Three of these four subtotal estimate results are lower than the estimate results in the meta-analysis across all the interventions.

Table 3.

Results of sensitivity analysis comparing overall and subtotal estimates of the effect on mean percentage weight change of DPP-based eHealth interventions from a meta-analysis including all interventions and a meta-analysis that included only interventions tested in studies with methodological quality score of ≥ 6/10

| Subtype | Total number of participants | Heterogeneity (I2) | Estimate of mean percentage weight change (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions included | |||

| Overall | |||

| All interventions | 2097 | 88.2% | −3.98% (−4.49%, −3.46%) |

| Only interventions tested in studies with quality scores ≥ 6/10 | 1330 | 80.7% | −3.40% (−3.94%, −2.85%) |

|

| |||

| Stand-alone interventions | |||

| Interventions from all studies | 822 | 82.4% | −3.34% (−4.00%, −2.68%) |

| Only interventions tested in studies with quality scores ≥ 6/10 | 822 | 82.4% | −3.34% (−4.00%, −2.68%) |

|

| |||

| Interventions delivered remotely | |||

| Interventions from all studies | 861 | 78.4% | −4.31% (−5.26%, −3.37%) |

| Only interventions tested in studies with quality scores ≥ 6/10 | 255 | 34.6% | −4.14% (−5.60%, −2.67%) |

|

| |||

| Interventions delivered face-to-face | |||

| Interventions from all studies | 414 | 94.5% | −4.65% (−6.63%, −2.67%) |

| Only interventions tested in studies with quality scores ≥ 6/10 | 253 | 87.0% | −3.33% (−5.07%, −1.59%) |

Interventions tested in studies with methodological quality scores ≥ 6/10: (Tate et. al., 2003 (a&b); Estabrooks and Smith Ray, 2008; McTigue et. al., 2009; Bennett et. al., 2010; Wing et. al., 2010 (study1&2); Ma et. al., 2013; Ackermann et. al., 2014 (a&b); Leahey et. al., 2014 (a&b); Block et. al., 2015; Fukuoka et. al., 2015; Thomas et. al., 2015; Fischer et. al., 2016)

Visual inspection, revealed an asymmetrical appearance of the funnel plot with a noticeable gap in the lower right corner (Figure 3). This may be an indication of the absence in the published literature of smaller studies without statistically significant findings (Higgins JPT, 2011). Also noticeable was one study with a larger than expected effect (Outlier: (Thomas and Wing, 2013)). Egger’s test showed no evidence of small-study effects (p=0.421).

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of data from 25 DPP-based eHealth interventions

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we reviewed published studies of DPP-based eHealth interventions which may be scalable to reach large numbers of adults at high-risk for developing T2D. However, the demographic characteristics of the samples of the DPP-based eHealth intervention studies are not reflective of the racial/ethnic and educational diversity of the sample of the original DPP trial. The DPP-based eHealth interventions have been studied in samples in which the majority of the participants were white and college educated. Given that in the U.S. the burden of type 2 diabetes disproportionally affects certain ethnic/racial subpopulations including Asian American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic black adults (CDC, 2014), and adults with lower educational attainment (Schiller et al., 2012), a priority for future research is to determine whether DPP-based eHealth interventions are effective in promoting weight loss in more racially/ethnically and educationally diverse samples. It may be possible to achieve greater racial/ethnic and educational diversity in future DPP-based eHealth intervention research by expanding recruitment from health care settings into churches, workplaces, and other community settings (Whittemore, 2011). There was only one trial of a Spanish-language DPP-based eHealth intervention identified, in which participants were recruited from a federally qualified health center (Fischer et al, 2016). This trial is particularly compelling since Hispanic adults that speak predominately Spanish and have limited English proficiency have been shown to be at increased risk for receiving inadequate preventive health services (Derose, Escarce, & Lurie, 2007).

The overall meta-analysis estimate across all the interventions of the effect on mean percentage weight loss at up to 15-months follow-up was −3.98%. In a previous meta-analysis, an overall estimate across DPP-based interventions of the effect on mean percentage weight loss was −3.99%, and a subtotal estimate across DPP-based eHealth interventions was −4.20% (Ali et al., 2012). The lower effect sizes seen in this review may be in part be due the inclusion of a greater number and variety of eHealth interventions. Whereas only four eHealth interventions were included in the past review of DPP-based interventions modified to the local context or delivered via eHealth, 26 eHealth interventions are included in the present review. Future research is needed to determine which eHealth approaches contribute to improved health outcomes as well as improved engagement, as attrition in studies included in this review varied considerably. Considerable heterogeneity was found to exist among DPP-based eHealth interventions, which has been found to also be the case in other DPP-based interventions adapted for real world delivery (Ali et al., 2012; Whittemore, 2011).

While some DPP-based eHealth interventions were stand-alone interventions with either no behavioral support from a counselor or behavioral support that was limited to a single baseline orientation (35%), the majority (65%) of the interventions included behavioral support from a counselor post-baseline, given either remotely, with communication technology (ie. online messages, email, telephone) and/or through face-to-face contacts (individual or group). There were differing subtotal estimates across the stand-alone interventions (−3.34%), vs. across the interventions with behavioral support remotely (−4.31%), vs. across the interventions with behavioral support face-to-face (−4.65%). Thus, behavioral support may enhance the efficacy of DPP-based eHealth interventions on weight loss. Similar findings have been shown in the literature of eHealth interventions intended to treat depression and anxiety (Baumeister et al., 2014).

In our sensitivity analysis, the summary estimates of the effect on weight loss of DPP-based eHealth interventions were slightly affected by the inclusion of studies of limited methodological quality. The asymmetry of the funnel plot with a gap in the lower right corner, may be an indication that smaller studies of DPP-based eHealth with nonsignificant findings may not be represented in the published literature. If this type of publication bias does exist in eHealth DPP-based intervention studies, it may lead to overestimation of the efficacy on mean percentage weight loss in meta-analyses.

The findings of the present study need to be viewed in light of a number of limitations. In some cases limited information was available on the components of the interventions. Future systematic reviews of DPP-based eHealth interventions will benefit from the improved reporting in eHealth research (Eysenbach & CONSORT-EHEALTH Group, 2011). Data from cohort studies with or without a control as well as data from randomized controlled trials was included in this review. While inclusion of data from observational studies can benefit systematic reviews when gaps exist in the evidence base of randomized controlled trials, the risks of introducing additional sources of bias are increased. It is often recognized that participants in studies testing interventions that promote weight loss may use other weight-loss programs or products during the interventions, a confounder that was reported in only one of the studies (Ma et al., 2013).

In this review aimed to explore how the offering of behavioral support may impact the efficacy on weight loss of DPP-based eHealth interventions; however, there are a number of questions regarding DPP-based eHealth interventions that remain unanswered. Of the 26 eHealth DPP-based eHealth interventions, in all but four cases (Ackermann et al., 2014; Sepah et al., 2014; Wing et al., 2010) there was a face-to-face baseline orientation. Offering a baseline orientation included offering technical assistance for participants in initiating the use of the eHealth technologies. It is possible that this technical assistance may have resulted in more frequent use and/or more informed use of the eHealth technologies.

A variety of eHealth delivery approaches were employed in the DPP-based interventions, including Web-based applications, mobile phone applications, text messages, DVDs, interactive voice response telephone calls, telehealth video conferencing, and video on-demand programing. We chose to only look at the effect that the inclusion of different types of behavioral support may have on the outcome of weight loss in the stratified meta-analysis. This decision was based on the link between behavioral support and adherence and the cost of including human behavioral support in eHealth interventions. Analysis in future reviews of the differential impact of the distinct eHealth approaches would be an important contribution to the literature.

Another question that remains unanswered is whether the beneficial effects on weight loss of DPP-based eHealth interventions vary by the amount of contact provided by counselors to users of these interventions. A direct dose-response relationship between the number of sessions offered to users and outcomes on weight loss has been demonstrated in a meta-analysis that included in-person DPP-based interventions and eHealth DPP-based interventions (Ali et al, 2011). However, whether there is a direct dose-response relationship between the quantity of behavioral counseling via eHealth interventions offered to users and outcomes remains unanswered (Baumeister et al., 2014). Future DPP-based eHealth intervention research of the effect on weight loss of differing doses of behavioral counseling delivered via communication technologies and/or in-person is warranted. The impact of behavioral counseling on participation in DPP-based eHealth interventions also needs to be evaluated.

Conclusions

The evidence of the efficacy on weight loss of eHealth DPP-based interventions is promising but still preliminary due to the heterogeneity of intervention components and the limited number of higher methodological quality trials. There may be beneficial effects when eHealth interventions include behavioral support given by counselors either remotely with communication technology or through face-to-face contacts. Given the burden of T2D among certain racial/ethnic minority populations and among individuals with disadvantaged socioeconomic status, DPP-based eHealth interventions that are sensitive to cultural differences and accessible for adults with limited resources need to be developed and evaluated.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Preliminary eHealth Diabetes Prevention Program intervention research is promising.

Interventions that offered counselor support post-baseline were the most effective.

Research is needed in diverse populations disproportionately affected by diabetes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers T32NR007088, K23NR014661].

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Ms. Gloria Y Won from the University of California, San Francisco.

Abbreviations

- DPP

The Diabetes Prevention Program

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ackermann RT, Finch EA, Brizendine E, Zhou H, Marrero DG. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into the community. The DEPLOY Pilot Study. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann RT, Sandy LG, Beauregard T, Coblitz M, Norton KL, Vojta D. A randomized comparative effectiveness trial of using cable television to deliver diabetes prevention programming. Obes. 2014;22:1601–1607. doi: 10.1002/oby.20762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrendt AD, Kattelmann KK, Rector TS, Maddox DA. The effectiveness of telemedicine for weight management in the MOVE! program. J Rural Health. 2014;30:113–119. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldana S, Barlow M, Smith R, Yanowitz F, Adams T, Loveday L, Merrill RM. A worksite diabetes prevention program: two-year impact on employee health. AAOHN J. 2006;54:389–395. doi: 10.1177/216507990605400902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali MK, Echouffo-Tcheugui J, Williamson DF. How effective were lifestyle interventions in real-world settings that were modeled on the Diabetes Prevention Program? Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:67–75. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atienza AA, Patrick K. Mobile health: The killer app for cyberinfrastructure and consumer health. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:S151–S153. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azar KM, Aurora M, Wang EJ, Muzaffar A, Pressman A, Palaniappan LP. Virtual small groups for weight management: an innovative delivery mechanism for evidence-based lifestyle interventions among obese men. Transl Behav Med. 2015;5:37–44. doi: 10.1007/s13142-014-0296-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister H, Reichler L, Munzinger M, Lin J. The impact of guidance on Internet-based mental health interventions: A systematic review. Internet Interv. 2014;1:205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2014.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GG, Herring SJ, Puleo E, Stein EK, Emmons KM, Gillman MW. Web-based weight loss in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Obes. 2010;18:308–313. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GG, Steinberg DM, Stoute C, Lanpher M, Lane I, Askew S, Foley PB, Baskin ML. Electronic health (eHealth) interventions for weight management among racial/ethnic minority adults: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2014;15(Suppl 4):146–158. doi: 10.1111/obr.12218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block G, Azar KM, Romanelli RJ, Block TJ, Hopkins D, Carpenter HA, Dolginsky MS, Hudes ML, Palaniappan LP, et al. Diabetes prevention and weight loss with a fully automated behavioral intervention by email, web, and mobile phone: a randomized controlled trial among persons with prediabetes. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e240. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boltri JM, Davis-Smith YM, Seale JP, Shellenberger S, Okosun IS, Cornelius ME. Diabetes prevention in a faith-based setting: results of translational research. J Public Health Manag Prac. 2008;14:29–32. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000303410.66485.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes Report Card 2014. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report: Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC. The handbook of research synthesis & meta-analysis. 2. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program: baseline characteristics of the randomized cohort. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1619–29. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.11.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks PA, Smith-Ray RL. Piloting a behavioral intervention delivered through interactive voice response telephone messages to promote weight loss in a pre-diabetic population. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G CONSORT-EHEALTH Group. CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of Web-based and mobile health interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13:e126. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer HH, Fischer IP, Pereira RI, Furniss AL, Rozwadowski JM, Moore SL, Durfee MJ, Raghunath SG, Tsai AG, et al. Text message support for weight loss in patients with prediabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2016 doi: 10.2337/dc15-2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka Y, Gay CL, Joiner KL, Vittinghoff E. A novel diabetes prevention intervention using a mobile app: a randomized controlled trial with overweight at risk. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:223–237. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, Brancati FL, Albright A Primary Prevention of Diabetes Working Group. Primary prevention of type 2 diabetes: integrative public health and primary care opportunities, challenges and strategies. Fam Pract. 2012;29(Suppl 1):i13–i23. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernan WH, Brandle M, Zhang P, Williamson DF, Matulik MJ, Ratner RE, Lachin JM, Engelgau MM. Costs associated with the primary prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:36–47. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, GS . Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [updated March 2011] [Google Scholar]

- Klein B, Austin D, Pier C, Kiropoulos L, Shandley K, Mitchell J, Gilson K, Ciechomski L. Internet-based treatment for panic disorder: Does frequency of therapist contact make a difference? Cognitive behaviour therapy. 2009;38:100–113. doi: 10.1080/16506070802561132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Christophi CA, Hoffman HJ, Brenneman AT, Brown-Friday JO, Goldberg R, Venditti E, et al. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program outcomes study. Lancet. 2009;374:1677–1686. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61457-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MK, Kriska AM, Venditti EM, Semler LN, Miller RG, McDonald T, Siminerio LM, Orchard TJ. A novel approach to diabetes prevention: evaluation of the group lifestyle balance program delivered via DVD. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;90:e60–e63. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leahey TM, Thomas G, Fava JL, Subak LL, Schembri M, Krupel K, Kumar R, Weinberg B, Wing RR. Adding evidence-based behavioral weight loss strategies to a statewide wellness campaign: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:1300–1306. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Yank V, Xiao L, Lavori PW, Wilson SR, Rosas LG, Stafford RS. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program lifestyle intervention for weight loss into primary care: a randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:113–121. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTigue KM, Conroy MB, Hess R, Bryce CL, Fiorillo AB, Fischer GS, Milas NC, Simkin-Silverman LR. Using the internet to translate an evidence-based lifestyle intervention into practice. Telemedicine J E. 2009;15:851–858. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moin T, Ertl K, Schneider J, Vasti E, Makki F, Richardson C, Havens K, Damschroder L. Women veterans’ experience with a web-based Diabetes Prevention Program: a qualitative study to inform future practice. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e127. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ockene JK, Schneider KL, Lemon SC, Ockene IS. Can we improve adherence to preventive therapies for cardiovascular health? Circulation. 2011;124:1276–1282. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.968479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagoto SL, Waring ME, Schneider KL, Oleski JL, Olendzki E, Hayes RB, Appelhans BM, Whited MC, Busch AM, et al. Twitter-delivered behavioral weight-loss interventions: a pilot series. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4:e123. doi: 10.2196/resprot.4864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatt GA, Seidel MC, Powell RO, Zgibor JC. Comparative effectiveness of lifestyle intervention efforts in the community: results of the rethinking eating and activity (REACT) study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:202–209. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritterband LM, Thorndike FP, Cox DJ, Kovatchev BP, Gonder-Frederick LA. A behavior change model for internet interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38:18–27. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9133-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepah SC, Jiang L, Peters AL. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into an online social network: validation against CDC standards. Diabetes Educ. 2014;40:435–443. doi: 10.1177/0145721714531339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller JS, Lucas JW, Peregoy JA. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2011. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2012;10(256) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoyen JA, Rutledge T, Wiese JA, Woods GN. Evaluation of TeleMOVE: a telehealth weight reduction intervention for veterans with obesity. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49:628–633. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9690-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate DF, Finkelstein EA, Khavjou O, Gustafson A. Cost effectiveness of internet interventions: review and recommendations. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38:40–45. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9131-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate DF, Jackvony EH, Wing RR. Effects of internet behavioral counseling on weight loss in adults at risk for type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:1833–1836. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JG, Leahey TM, Wing RR. An automated internet behavioral weight-loss program by physician referral: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:9–15. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JG, Wing RR. Health-e-call, a smartphone-assisted behavioral obesity treatment: pilot study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2013;1:e3. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadheim LM, McPherson C, Kassner DR, Vanderwood KK, Hall TO, Butcher MK, Helgerson SD, Harwell TS. Adapted diabetes prevention program lifestyle intervention can be effectively delivered through telehealth. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36:651–656. doi: 10.1177/0145721710372811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R. A systematic review of the translational research on the Diabetes Prevention Program. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:480–491. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0062-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing RR, Crane MM, Thomas JG, Kumar R, Weinberg B. Improving weight loss outcomes of community interventions by incorporating behavioral strategies. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2513–2519. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.183616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfenden L, Brennan L, Britton BI. Intelligent obesity interventions using smartphones. Prev Med. 2010;51:519–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.