Abstract

Drawing on a two-wave, multimethod, multi-informant design, this study provides the first test of a process model of spillover specifying why and how disruptions in the coparenting relationship influence the parent–adolescent attachment relationship. One hundred ninety-four families with an adolescent aged 12–14 (M age = 12.4) were followed for 1 year. Mothers and adolescents participated in two experimental tasks designed to elicit behavioral expressions of parent and adolescent functioning within the attachment relationship. Using a novel observational approach, maternal safe haven, secure base, and harshness (i.e., hostility and control) were compared as potential unique mediators of the association between conflict in the coparenting relationship and adolescent problems. Path models indicated that, although coparenting conflicts were broadly associated with maternal parenting difficulties, only secure base explained the link to adolescent adjustment. Adding further specificity to the process model, maternal secure base support was uniquely associated with adolescent adjustment through deficits in adolescents’ secure exploration. Results support the hypothesis that coparenting disagreements undermine adolescent adjustment in multiple domains specifically by disrupting mothers’ ability to provide a caregiving environment that supports adolescent exploration during a developmental period in which developing autonomy is a crucial stage-salient task.

The marital relationship forms the cornerstone of family well-being. When parents argue, the conflict can have broad, pernicious repercussions for family and child functioning (Cummings & Davies, 2010; Erel & Burman, 1995). Breakdowns in the coparenting relationship, in which childrearing is the primary emphasis, appears to uniquely increase children’s vulnerability to adjustment problems (Chen & Johnston, 2012; Jouriles et al., 1991; Katz & Low, 2004), and help explain how broader marital difficulties undermine the parent– child relationship (Katz & Gottman, 1996; Margolin, Gordis, & John, 2001; Stroud, Meyers, Wilson, & Durbin, 2015). Parents’ difficulties managing conflicts in the coparenting relationship may impair their ability to serve as reliable and sensitive attachment figures. Given the central importance of attachment to parents during the transition to adolescence, this study seeks to identify precisely how and why coparenting difficulties constitute a risk for adolescent adjustment problems from an attachment framework.

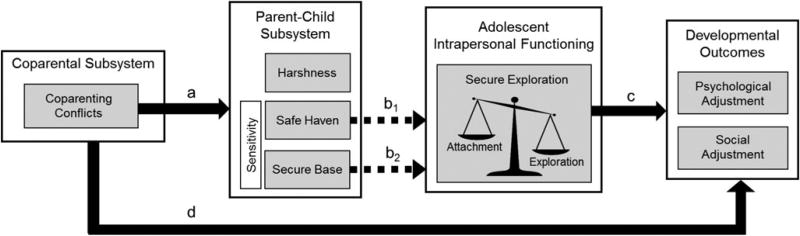

We still know relatively little about the consequences of coparenting disruptions for child attachment (Caldera & Lindsey, 2006; Teubert & Pinquart, 2010). This gap is especially apparent in adolescence, where research has lagged behind in identifying precisely what a “sensitive” caregiving environment means in the face of changes in the nature of adolescents’ attachment needs. Building on research with parents of infants and young children (e.g., Brown, Schoppe-Sullivan, Mangelsdorf, & Neff, 2010; Caldera & Lindsey, 2006), we propose a process model (see Figure 1) whereby conflict in the coparenting relationship sets in motion an unfolding series of processes in which (a) parents are less able to provide sensitive care in response to adolescents’ bids for support (Path a), (b) experiencing subpar caregiving undermines adolescents’ balance of attachment and exploration (Paths b1 and b2), and (c) this ultimately places adolescents at greater risk for a range of psychological and social adjustment problems (Path c).

Figure 1.

A conceptual illustration of the hypothesized process model of the consequences of coparenting conflicts for adolescent development across family subsystems. Coparenting conflicts are proposed to undermine parenting, which, in turn, disrupts adolescents’ secure exploration, represented by a balance between attachment and exploration. Less secure exploration, in turn, negatively impacts social and psychological adjustment.

Conflict in the Coparenting Relationship and Spillover

Guided by family systems theory, investigations into the consequences of coparental conflicts for child adjustment have identified parenting difficulties as a primary mediating factor (Jones, Shaffer, Forehand, Brody, & Armistead, 2003; Margolin et al., 2001). According to the spillover hypothesis, negativity stemming from disruptions in one family subsystem (e.g., the coparenting relationship) can “spill over” into other subsystems (e.g., the parent–child relationship; Erel & Burman, 1995). Intense feelings of anger or distress over child-rearing disagreements may overwhelm parents’ self-regulatory abilities and increase their tendency to replay hostile strategies in subsequent interactions with their child (Sturge-Apple, Davies, & Cummings, 2006). Similarly, preoccupation with partners’ disapproval over childrearing decisions may undermine adult’s confidence and sense of efficacy in their role as parents (Merrifield & Gamble, 2013). Accordingly, research has shown that parents who engage in more frequent and intense disagreements over childrearing evidence more harsh parenting and reduced sensitivity during parent–child interactions (Dorsey, Forehand, & Bordy, 2007; Feinberg, Kan, & Hetherington, 2007; O’Leary & Vidair, 2005; Sturge-Apple et al., 2006). In turn, both parental harshness and insensitivity predict child adjustment problems, including internalizing and externalizing problems and social difficulties (e.g., prosocial behavior and peer rejection; Beijersbergen, Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2012; Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz, & Simons, 1994; McLeod, Weisz, & Wood, 2007; Padilla-Walker, Neilson, Mathew, & Day, 2016).

Moving forward, developing a more precise understanding of the unfolding consequences of disruptions in coparenting will require identifying which aspects of parental caregiving are most important for explaining the negative effects of coparenting conflict on adolescent adjustment. Given the importance of the parent–child attachment relationship for adolescent development (e.g., Allen, 2008), the current study seeks to advance the literature by testing whether parents’ inability to cooperatively negotiate their parental roles hinder their ability to serve as sensitive and supportive attachment figures. No studies have yet examined this hypothesis with an adolescent sample. However, coparenting conflicts have been linked to insecure attachment in infancy, suggesting that the coparental relationship does play a role in shaping the parent–child attachment relationship (Brown et al., 2010; Caldera & Lindsey, 2006).

Prior evidence points to parental sensitivity as an important aspect of the caregiving environment, promoting secure attachment in both young children and adolescents (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, 2003; Booth-LaForce et al., 2014; De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997). Sensitivity refers to parents’ capacity to recognize and correctly interpret their child’s emotional expressions and needs, and to respond to these signals in an appropriate way (Ainsworth, Bell, & Stayton, 1974; Goldberg, Grusec, & Jenkins, 1999). Parental sensitivity in response to child distress in particular appears to promote better social and psychological functioning over and above parental warmth and parents’ sensitivity in nondistress (e.g., play) situations (Davidov & Grusec, 2006; Leerkes, Blankson, & O’Brien, 2009; McElwain & Booth-LaForce, 2006). Grounded in this research, several attachment-based therapeutic programs have evidenced effectiveness in reducing children’s problem behaviors by improving parental sensitivity (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, Mesman, Alink, & Juffer, 2008; Marvin, Cooper, Hoffman, & Powell, 2002; Moretti & Obsuth, 2009).

These findings suggest that deficits in parental sensitivity could be a particularly important aspect of the caregiving environment undermined by difficulties in the coparenting relationship. However, the definition of sensitivity as “identifying child signals and responding appropriately” encompasses such a broad range of parenting behaviors that it is difficult to draw precise conclusions from previous work regarding the specific processes that may be more or less relevant for children’s adjustment. By contrast, attachment researchers have advanced two aspects of parental sensitive caregiving that have particular relevance for child attachment: safe haven and secure base (George & Solomon, 2008; Kerns, Mathews, Koehn, Williams, & Siener-Ciesla, 2015). Integrating this more differentiated concept of parental sensitivity into models of spillover stands to increase specificity in our understanding of the unfolding processes linking coparenting conflict with adolescent attachment.

Specifying Attachment-Relevant Dimensions of Sensitivity

Parental safe haven support refers to a coordinated set of processes that relieve the child’s distress and protect them from danger (e.g., strangers or illness; Feeney, 2004; Nickerson & Nagle, 2005). Safe haven incorporates elements of traditional sensitivity in that recognizing, appropriately labeling, and responding to their child’s bids for attention allow the parent to accurately identify distress cues and enact a develop-mentally appropriate approach for relief. In the context of a parent–adolescent interaction, parental safe haven involves a pattern of attending to adolescents’ distress or worry, expressing empathic concern, emotional support, and comfort, and behaving to directly resolve the distress-causing situation (e.g., offering solutions). Parental secure base support, in contrast, refers to behaviors functioning to promote the child’s autonomous exploration (Feeney & Thrush, 2010; Kerns et al., 2015). In the context of a parent–adolescent interaction, secure base is evidenced by parents’ encouragement to persevere through discomfort, autonomy support, and praise for adolescents’ efforts to explore (e.g., coming up with their own solutions). However, just as with safe haven parenting, secure base requires that parents recognize their child’s need for encouragement as well as their limitations in order to balance support for exploration while refraining from overstimulation or extreme distress.

Only relatively recently have researchers of attachment in adolescence begun to distinguish between parental safe haven and secure base support, despite a long history of conceptual distinctions between these two functions of parenting (e.g., Allen et al., 2003; Kerns et al., 2015). As a result, we still know relatively little about how these two aspects of the caregiving environment may be associated with broader family disruptions (e.g., coparenting conflicts) and adolescent adjustment. Given the demonstrated associations between coparenting difficulties on parental sensitivity, the first aim of the current study is to compare parental safe haven, secure base, and harshness as potential mediating processes linking conflict in the coparenting relationship and adolescent social and psychological adjustment. We propose that coparenting conflicts ultimately disrupt parents’ ability to provide a caregiving environment promoting adolescents’ attachment security. In addition, just as research with young children has demonstrated that parental sensitivity in response to children’s distress is particularly relevant for child attachment (e.g., McElwain & Booth-LaForce, 2006), parental caregiving will be assessed in the context of an experimental design in which adolescents are asked to discuss with their parent a distressing or worrisome issue outside of the parent–child relationship. Previous studies have observed parents and adolescents in a similar context in order to capture attachment-relevant characteristics of the parent–child relationship (e.g., Allen et al., 2002, 2003). The current study seeks to extend this research by applying a novel observational system designed to distinguish between parents’ caregiving behaviors based on their function in promoting safe haven or secure base in response to adolescents’ bids for support.

Supporting Adolescents’ Secure Exploration

The final step in specifying our process model of coparenting conflict involves identifying precisely how and why disruptions to parents’ ability to provide a safe haven (Figure 1, Path b1) and a secure base (Figure 1, Path b2) ultimately undermine adolescent adjustment. According to attachment theorists, these two forms of sensitive parenting work in concert to fulfill two attachment-relevant goals: (a) alleviating children’s doubts and distress about environmental challenges and (b) instilling the confidence necessary to engage in exploratory goals that are relevant to the mastery of social and physical environments (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970; McElhaney, Allen, Stephenson, & Hare, 2009). Meeting children’s attachment needs in turn sets the foundation for a balance between attachment and exploration characterized by a pattern of approaching challenges with confidence, eagerness, agency, resourcefulness, flexibility, high frustration tolerance, and persistence in the face of disappointment, a pattern referred to as “secure exploration” (Grossman, Grossman, Kindler, & Zimmermann, 2008). These component aspects of secure exploration in turn are proposed to promote adaptive social and psychological adjustment by aiding children in meeting important developmental milestones (e.g., Davies, Manning, & Cicchetti, 2013; Feeney & Van Vleet, 2010) and are conceptualized as personal assets central to promoting resiliency in adolescence (e.g., Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005).

No research to date has specifically distinguished between safe haven and secure base support as predictors of adolescents’ secure exploration. On the one hand, based on research with young children, we might expect that both parental safe haven and secure base play a unique role (e.g., Grossman et al., 2008; Kerns et al., 2015). Parents’ provision of safe haven is designed to help mitigate the stress and negative affect associated with external (e.g., peer conflict) or internal (e.g., disappointment) challenges. Therefore, safe haven supports may promote secure exploration by helping adolescents to modulate their emotions in ways that reduce distress and promote engagement in the task at hand. Repeated failure of parents to provide safe haven support may, instead, undermine adolescent’s confidence in their parents’ availability when needed, a central factor promoting secure exploration. Similarly, the function of secure base caregiving is to promote the child’s efficacy, autonomy, and confidence in mastering environmental challenges. Parent’s encouragement, autonomy-support, and praise may directly signal adolescents that tackling a challenge or trying something new is both a safe and worthwhile goal. In turn, when this secure base support is absent, children may not have the confidence and agency central to secure exploration.

On the other hand, as adolescents move toward increasingly self-regulating their distress (i.e., Allen & Miga, 2010), parental secure base support may take on an increasingly important role. Especially as adolescents develop closer safe haven relationships with peers (e.g., Markiewicz, Lawford, Doyle, & Haggart, 2006; Nickerson & Nagle, 2005), parental secure base may become a stronger mechanism of parental influence on children’s secure exploration. In addition, establishing greater autonomy becomes a central developmental challenge as children enter adolescence. Given that parental secure base directly encourages and supports children’s autonomy and persistence in the face of challenge, secure base support may be the primary parental predictor of secure exploration in adolescence. Therefore, distinguishing between safe haven and secure base caregiving in predicting adolescent secure exploration could be crucial for untangling shifting caregiving needs as children mature.

Returning to our broader conceptual model (Figure 1), our second aim is to test whether adolescent’s secure exploration differentially explains associations between impairments in maternal caregiving (Paths b1 and b2) as a result of coparenting difficulties and adolescents’ adjustment (Path c). Capitalizing on social evaluation as a stage-salient stressor (Somerville, 2013), we challenged adolescent participants to prepare and perform a speech about themselves. Their mother was present, but not instructed to assist. In this context, secure exploration is reflected in adolescent’s overall ability to (a) regulate distress and motivate task engagement, (b) draw on internal resources to problem solve independently, and (c) maintain relatedness toward their parent in order to comfortably access parental support as needed. Therefore, the speech task provides an opportunity to capture a snapshot of adolescent’s behavioral expressions of the attachment–exploration balance.

The Current Study

In summary, the current study is designed to test a theoretically driven process model of the unfolding consequences of coparenting conflict as a risk factor undermining adolescents’ social and psychological adjustment. Guided by an attachment framework, we propose that conflict in the coparenting relationship disrupts parents’ ability to serve as sensitive caregivers, even in the face of adolescent’s bids for support. Drawing on a two-wave, multimethod design, we first examine how coparenting conflicts interrupt parental caregiving by comparing maternal safe haven and secure base as intervening factors in the association between coparenting conflict and adjustment. We next increase the specificity of this test by comparing the predictive value of these two attachment-relevant aspects of parental sensitivity against an assessment of maternal harshness (i.e., hostility and intrusive control). Harsh parenting has been examined in previous models as an indicator of the direct spillover of hostility from the coparental to the parent–child subsystem (Feinberg et al., 2007; Sturge-Apple et al., 2006), and a consistent precursor to a range of adolescent adjustment problems (e.g., Barber, 2002; Buehler, Benson, & Gerard, 2006; Padilla-Walker et al., 2016). Therefore, we propose to examine whether the impact of coparenting conflicts on parents’ ability to meet their adolescents’ attachment needs helps to explain the association between difficulties in the coparenting relationship and adolescent adjustment over and above the broader recapitulation of hostility from one subsystem to another.

Next, we seek to further test the unfolding impact of coparenting conflicts on the parent–adolescent attachment relationship by including an assessment of adolescents’ secure exploration as a behavioral marker of attachment security in our process model. Drawing on recent advances in the attachment literature (e.g., George & Solomon, 2008; Kerns et al., 2015), this study seeks to break new ground by specifying the form of parental caregiving (i.e., safe haven or secure base) with the greatest importance for adolescents’ secure exploration. In addition, given the importance of confident, autonomous exploration for adolescent development, we aim to understand whether adolescents’ secure exploration in tackling a social evaluative challenge helps to explain why disruptions in maternal sensitivity ultimately undermine adolescents’ social and psychological adjustment. Finally, family socioeconomic status and adolescent gender were included as covariates based on empirical evidence for their correlation with coparenting conflict, parenting, and adolescent adjustment (e.g., Feinberg et al., 2007; O’Leary & Vidair, 2005; Schoppe-Sullivan & Mangelsdorf, 2013).

Method

Participants

One hundred ninety-four families participated in this study from a moderate-sized city in the Northeast. Families were recruited through school districts, family-centered internet sites, and flyers. They were accepted into the study if (a) they had an adolescent between the ages of 12 and 14, (b) the target adolescent and two parental figures had been living together for at least the previous 3 years, (c) at least one parental figure was the biological parent of the target teen, (d) all participants were fluent in English, and (e) the target adolescent had no significant cognitive impairments. Families were followed over two annual measurement occasions spaced 1 year apart. Adolescents averaged 12.4 years of age at Wave 1. Approximately 50% of the adolescents in this sample were female (n = 97). The median household income for this sample ranged from $55,000 to $74,999 with 14% of the sample reporting a household income under $23,000. Median parental education was an associate’s degree, with most parents (85%) attending at least some college. A smaller subset of the adults in this sample (12%) earned a high school diploma or a GED as their highest degree. The majority of parents were married or engaged (87%), and another 12% reported being in a committed, long-term relationship. Children lived with their biological mother in the vast majority of cases (94%). The sample largely identified themselves as White (74%), followed by Black (13.5%) and mixed race (10%), and a number identified as being of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity (12%). The retention rate from Wave 1 to Wave 2 was 93% (180 families).

Procedures

At each of the two waves of data collection, mothers, fathers, and their adolescent visited the laboratory for a single, 3-hr visit. The laboratory included one room designed to resemble a living room and equipped with audiovisual equipment to capture family interactions, as well as other comfortable rooms for participants to independently complete confidential interviews, computerized assessments, and questionnaires. Families received monetary payments for their participation.

Dyadic interactions

During the second wave of data collection, mothers and teens participated in two structured interactions: a support task and a speech task. Task order was counterbalanced across families, and each task was separated by questionnaires and activities.

Support task

The support task was designed to elicit maternal caregiving in an ecologically valid manner. Prior to beginning the task, adolescents were asked to independently write down three topics or issues outside of the parent–child relationship that caused them to be upset, stressed, or worried. They were then asked to select one of these topics to discuss with their mother. Mothers and their teens were brought into the videorecording room and seated comfortably in living room furniture, facing one another. Adolescents were asked to share the topic with their mother, as well as how they feel about it and why. The participants were then asked to discuss this topic “as they normally would at home.” They were given 7 min to discuss the issue, and their interactions were videorecorded and saved for later coding. A similar task, in which teens were asked to discuss with their mothers a problem outside of their relationship, has been used previously to successfully capture similar parent–child dynamics (i.e., Furman & Shomaker, 2008).

Speech task

The speech task was designed to represent a developmentally appropriate social challenge for young adolescents. The adolescent participants were asked to give a 2-min speech about themselves (e.g., strengths and weaknesses or personal successes and failures) in front of a video camera and with their mother in the room. Based on the premise that social evaluation is a stage-salient fear during this period (e.g., Somerville, 2013), the task was designed to be moderately challenging, as teens were required to overcome feelings of distress or avoidance to plan and present the speech. A similar approach has been used previously to induce adolescent distress in the lab (e.g., Hostinar, Johnson, & Gunnar, 2015; Zimmermann, Mohr, & Spangler, 2009). To maximize the ecological validity of the task, participants were told that we were studying how adolescents communicate information about themselves in order to help teens better prepare for college and job interviews. We sought to emphasize the evaluative nature of the task by having the adolescents perform at a podium, looking directly into a prominent video camera. While only their mothers were present in the room, the adolescents were told that their speech would be subsequently evaluated by a research assistant on the project. Writing utensils and a stopwatch were provided. Prior to the 2-min speech, adolescents had a 5-min period to prepare.

Mothers were instructed to turn the camera on and off at the appropriate time using a manual control linked to the camera by a long wire. This allowed mothers to control the camera from anywhere in the room. Pushing the button on the control turned on a visible light on top of the camera as a signal it was recording. A buzzer went off in the room to signal the participants when to start and end the 2-min speech. Experimenters explained to mothers how and when to turn the camera on and off, but otherwise simply said they were “free to do whatever feels comfortable.” Instructions to mothers were kept vague in order to provide adolescents and their mothers the freedom to interact as much or as little as they desired and with minimal external prompts.

Finally, we tested whether the speech task elicited distress in early adolescence. Three independent coders, overlapping on 45% of the video records, provided a single, continuous score for adolescent distress from 1 (no distress) to 9 (intense distress), intraclass correlation (ICC) = 0.81, p < .001. Distress was defined as signs of emotional upset, including verbal, facial, or behavioral expressions of anger, sadness, or fear. High ratings reflected overt signals of intense distress (e.g., crying or yelling) that significantly interfered with their completion of the task. Coders’ provided a mean rating of 4.35 (SD = 1.68) on the 1 to 9 scale. Of the entire sample, only 1 adolescent (.05% of the sample) showed no signs of distress, and 23 (12% of the sample) showed minimal signs. Scores were normally distributed.

Measures

Coparenting conflict

Both mothers and fathers provided an assessment of the frequency of childrearing disagreements by each completing an abbreviated version of the Childrearing Disagreements Questionnaire (Jouriles et al., 1991). The abbreviated scale includes eight items assessing the frequency of interparental conflicts around common issues that arise in childrearing (e.g., “Doing the easy or fun things, but not too many of the hard or boring things in childcare” and “Babying our child”). Items were rated along a 5-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Internal consistency was satisfactory for moms’ (α = 0.77) and dads’ (α = 0.80) reports. Parents’ reports of the frequency of childrearing disagreements were summed and then averaged across parent to yield a single score for the frequency of childrearing disagreements (α = 0.81, M = 14.81, SD = 3.90).

Maternal parenting

To assess different aspects of parenting, we observed mothers’ behaviors toward her adolescent during the support task. Assessments of maternal parenting were carried out by independent and reliable coders using a single standardized observational system, the Caregiving Assessment Scale (Sturge-Apple, Martin, & Davies, 2015). Each behavioral dimension was assessed on a scale from 1 (never or rarely exhibited) to 9 ( frequently or intensely exhibited). Two trained observers provided assessments, overlapping on 20% of the video records in order to assess reliability.

Maternal secure base

The Caregiving Assessment Scale was developed to capture parental caregiving dimensions in terms of their function of promoting adolescent security and exploration. For each scale, the specific behaviors that serve a particular function (e.g., secure base) could take different forms and were not necessarily mutually exclusive. Trained raters were directed to focus, not on the form of mothers’ behavior, but on its meaning in relation to the ongoing interaction between the mother and adolescent. The secure base scale was designed to capture maternal behaviors functioning to encourage and reinforce adolescent autonomy and exploration around the worrisome topic. Although the specific behaviors may differ, mothers scoring high in secure base generally shared a common core of features, including (a) adopting an active listening style, (b) remaining engaged but letting adolescents take the lead in directing the discussion, (c) challenging adolescents to generate solutions and think more deeply, (d) expressing confidence in the adolescents’ capabilities, and (e) reinforcing adolescent initiative with praise and encouragement. Regardless of form, secure base behaviors shared the function of encouraging adolescents to think and explore the topic autonomously, even if this involved pushing adolescents beyond their comfort zone. However, this push occurred simultaneously with a sensitivity to the adolescent’s limits and a solid base of support not contingent on performance (e.g., expressing approval at the teen’s effort in solving the problem, even if he/she was ultimately unsuccessful). Interrater reliabilities for secure base indicated acceptable reliability (ICC = 0.71, p <, .001). Mothers also displayed a range of secure base behavior across families (M = 4.88, SD = 2.49).

Maternal safe haven. The safe haven scale captured the extent to which mothers’ behavior served to relieve adolescent distress. As with the secure base scale, the actual form of maternal behaviors differed, but tended to share common core of features, including (a) a sensitivity to adolescents’ distress and support-seeking signals, (b) expressions of empathic concern and understanding of the adolescents’ perspective, (c) soothing verbal (e.g., “Don’t worry, you can tell me anything” or “You’ve been studying so hard, I know you’re going to pass”) and nonverbal (e.g., touching the adolescents’ arm affectionately or facial expressions of concern) signals, and (d) attempts to directly address or fix the source of distress (e.g., “I’ll help you figure out the homework problem when we get home” or “You can try this …”). Mothers high in safe haven were sensitive and responsive to adolescents’ bids for affection, attention, relief, or assistance, regardless of the degree to which they sought to complete the task itself. Interrater reliabilities were for safe haven were 0.82 ( p < .001) and evidenced a normal distribution (M = 4.56, SD = 2.26).

Maternal harshness

Maternal harshness was assessed using two codes adapted from the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (Melby & Conger, 2001). Observers evaluated maternal hostility, assessing the degree to which mothers displayed curt, critical, harsh, disapproving, and demeaning behaviors toward the adolescent (M = 2.92, SD = 2.23). This included expressions of irritation, anger, or rejection through nonverbal signals (e.g., angry or contemptuous facial expressions), emotional expressions (e.g., irritated, curt tone, sarcasm, contempt, or actively ignoring), and angry or aggressive statements (e.g., denigrating remarks or criticisms). Mothers assigned higher scores for hostility commonly displayed personal attacks, criticisms, and statements that were hurtful or rejecting. Similarly, maternal control was assessed as mothers’ direct attempts to regulate the adolescent’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior (M = 4.50, SD = 2.64). High control was evident in mothers’ parent-centered (i.e., guided by the mother’s needs and desires) attempts to direct the adolescent to conform to the behaviors, opinions, expectations, or points of view desired by the mother, especially when differences in these areas were initially present. Interrater reliability was adequate for both hostility and control (ICC = 0.86, p < .001, and ICC = 0.78, p < .001, respectively). Observer ratings of maternal hostility and control were averaged, yielding a single score for maternal harshness in the support task (M = 3.61, SD = 2.24, α = 0.81). Similar scales have been employed previously with an adolescent sample (e.g., Buehler et al., 2006; Jaser & Grey, 2010).

Adolescent secure exploration

Observations of adolescents’ behavior during the speech task provided a measure of their secure exploration, conceptualized as a developmentally appropriate balance between attachment and exploration. Three trained raters (different from those who provided the validity assessment of adolescent distress) completed multiple, molar observational scales adapted to assess behavioral manifestations of secure exploration in the context of the parent–adolescent relationship. For the current study, we focus on three aspects of adolescents’ secure exploration: comfort, autonomy, and disengagement. The scales for adolescent’s comfort and autonomy were adapted from the Child Reactions to Interparental Disagreements coding system (Davies, 2015) and the disengagement scale was adapted from the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (Melby & Conger, 2001). Each of these scales was altered to reflect adolescents’ behavior in engaging with the challenge presented by the speech task. Observers considered the frequency, form, and meaning of each pattern of behavior as the adolescent moved through the preparation and giving of the speech, providing a single rating for each on a scale from 1 (very little or no evidence of this characteristics) to 9 (a whole lot of evidence of this characteristic).

First, comfort was defined as the degree to which the adolescent appeared to be relaxed, content, and comfortable engaging with the task. High comfort was reflected in facial expressions (e.g., calm/neutral or authentic smiling), posture (e.g., relaxed), open interest (e.g., positive tone of voice or asking questions), and general ease of behavior, while low comfort is indicated by intense distress and reflexive task avoidance (M = 5.63, SD= 2.66). Second, autonomy was defined by high degrees of confidence, agency, and independence in exploring the task (M = 4.89, SD = 2.56). High levels of confidence and autonomy were evident in (a) facial expressions, posture, and verbalizations indicative of confidence and pride; (b) a high degree of persistence and engagement in the task; and (c) reliance on internal resources to try to solve problems (e.g., listing points to bring up in the speech or asserting one’s own plan of action). To the last point, highly agentic and autonomous adolescents may still seek parental assistance; however, the nature of the bid to parents was generally instrumental (i.e., seeking help with a particular aspect of the task) as opposed to comfort seeking. Therefore, the quality of highly autonomous adolescents’ communications to parents were assertive, yet fall within the bounds of respectfulness toward the parent. Third, disengagement reflected adolescents’ apathetic, aloof, uncaring, and irritated attitude toward their parent. High disengagement was evidenced by verbalizations and behaviors meant to minimize the amount of time, contact, or effort the adolescent expended in interacting with the parent (e.g., ignoring the parent, withdrawing, responding to parents’ questions/commands with brief, wooden responses, or avoiding eye contact; M = 2.98, SD = 2.53). Coders’ ratings of adolescent disengagement were reverse-scored so that higher values reflected adolescents’ easy engagement with parents, in either asking for assistance or engaging in warm, affiliative interactions indicative of relatedness. Interrater agreement was 0.97, 0.95, and 0.95 for comfort, autonomy, and disengagement, respectively (all ps < .001). The three scales were averaged to yield a single score for adolescent secure exploration (α = 0.69).

Adolescent psychological adjustment problems

During the second wave of data collection, parents reported on their adolescent’s psychological adjustment using two subscales from the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). For each scale, parents were asked to respond to the degree to which each item was true of their child along a 3-point scale from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true). The internalizing problems subscale included 21 items reflecting adolescents’ anxious, depressed, and withdrawn behaviors (e.g., “My child is unhappy, sad, or depressed” and “My child would rather be alone than with others”). These items were summed into a single score for internalizing (αs = 0.91 for mothers’ and 0.86 for fathers’ reports). Similarly, the externalizing problems subscale included 30 items reflecting adolescents’ aggression and rule-breaking behaviors (e.g., “My child often gets into fights” and “My child is truant, skips school”). These were also summed, and evidenced adequate internal consistency (αs = 0.91 and 0.92 for mothers and fathers, respectively). Parents’ reports on each scale were summed within parent and then averaged together to yield a single score for parent reports of adolescent psychological problems (M = 11.18, SD = 9.58, α at the scale level = 0.74).

Adolescent social competence

Parents also provided reports of their adolescent’s social competence at Wave 2. Social competence was captured using two scales from the parent-report version of the secondary-level Social Skills Rating System (SSRS; Gresham & Elliott, 1990). The SSRS provides a list of social behaviors that are considered central to social competence in Grades 7–12 (Gresham & Elliott, 1990). For each item, parents described how often their child exhibits that behavior along a 3-point scale from 0 (never) to 2 (very often). For this study, we used two subscales from the SSRS: assertion (10 items; e.g., “Is self-confident in social situations such as parties or group outings”), assessing adolescents’ confidence and tendency to initiate social interactions, and cooperation (10 items; e.g., “Makes friends easily”), which captures their friendly and cooperative behavior. Items within each scale were summed for each reporter; αs ranged from 0.67 to 0.77 (M = 0.73). The four scales were then averaged to yield a single, parent-reported assessment of adolescent social competence where higher values reflect greater competence (α = 0.86, M = 12.90, SD = 2.61).

Socioeconomic status

Mothers and fathers completed a short demographic survey during the first wave of data collection. Parents reported on their family’s average yearly income. Mothers’ and fathers’ reports were averaged and ranged from less than $6,000 to over $125,000 (median = $55,000– $74,999). Each parent also reported his/her highest degree of education. Mothers ranged from 10th or 11th grade to doctoral degree (median = associate’s degree) and fathers from 8th or 9th grade to doctoral degree (median = some college). Each parent’s education and the average family income were standardized and averaged to yield a single score, where higher values reflect higher socioeconomic status.

Results

The means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations between study variables are presented in Table 1. All analyses were conducted using full information maximum likelihood estimation in Amos 22.0 to retain the full sample (Enders, 2001). In support of our predictions, associations among primary variables were correlated in the expected direction and were moderate in magnitude. Of note, adolescent gender was not correlated with any of the variables of interest.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for the primary variables in the analyses

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 Assessments | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 1. | Adolescent gender | — | — | — | |||||||||

| 2. | Family SES | 0.00 | 0.81 | .21** | — | ||||||||

| 3. | Child-rearing disagreements | 1.87 | 0.51 | −.04 | −.32** | — | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Wave 2 Assessments | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 4. | Maternal safe haven | 4.60 | 2.23 | −.06 | .15† | −.21** | — | ||||||

| 5. | Maternal secure base | 4.91 | 2.49 | .00 | .15* | −.25** | .37** | — | |||||

| 6. | Maternal harshness | 3.61 | 2.24 | .02 | −.28** | .37** | −.54** | −.31** | — | ||||

| 7. | Adolescent confidence | 5.85 | 1.98 | −.10 | .21** | .23** | .27** | .29** | −.25** | — | |||

| 8. | Social competence | 12.90 | 2.61 | −.07 | −.03 | −.26** | .25** | .28** | −.16* | .34** | — | ||

| 9. | Psychological problems | 5.56 | 4.69 | .02 | −.19* | .44** | −.21** | −.25** | .22** | −.33** | −.58** | — | |

Note: SES, Socioeconomic status.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p <, .01.

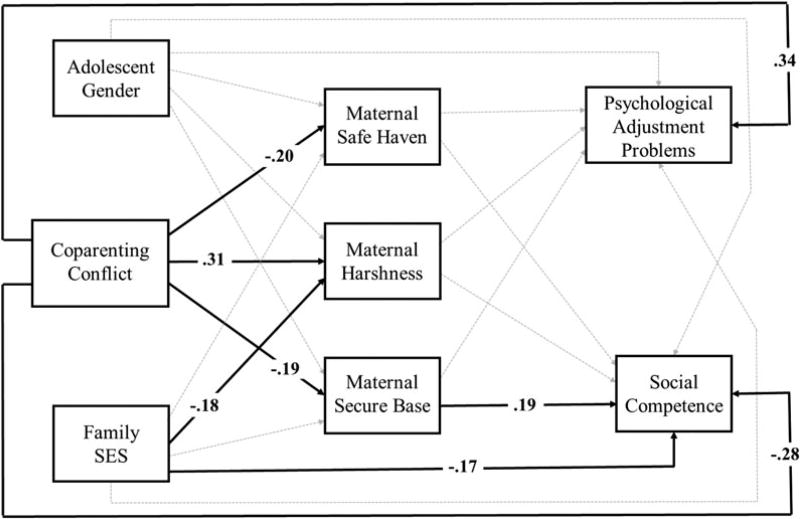

Testing maternal parenting as a mediator

To test our first hypothesis, a path model was used in which the three forms of maternal parenting (i.e., safe haven, secure base, and harshness) were specified as potential mediators of associations between parent reports of their coparenting conflict and both adolescent psychological problems and social competence. All possible paths were included in the model. In addition, covariances were specified between the exogenous predictors (i.e., adolescent gender, socioeconomic status, and coparenting conflict), between the three parenting variables, and between the two outcomes (i.e., social competence and psychological problems). This resulted in a model that was fully identified. As shown in Figure 1, parents’ reports of coparenting conflict at Wave 1 uniquely predicted all three forms of parenting in Wave 2. More frequent coparenting conflict was associated with more maternal harshness (β = 0.31, p < .01) and lower levels of maternal safe haven (β = −0.20, p < .01) and secure base behaviors (β = −0.19, p < .01) during the support task. Maternal secure base was in turn the only parenting behavior directly associated with adolescent adjustment also at Wave 2. Secure base positively predicted parent reports of their adolescents’ social competence (β = 0.19, p < .05).

As a further test of this mediational pathway, bootstrapping tests were performed, using the PRODCLIN software program (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007). This test indicated that the indirect path involving coparenting conflict, maternal secure base, and adolescent social competence was significantly different from zero, 95% confidence interval (CI) [–0.42, –0.01], even within a broader model specifying gender, socioeconomic status, and each other form of parenting behavior as predictors of social competence. In addition, interparental coparenting conflict continued to evidence a direct association with both adolescent social competence (β = –0.28, p < .01) and their psychological adjustment problems (β = 0.34, p < .01), indicating that maternal secure base only partially accounts for these links.

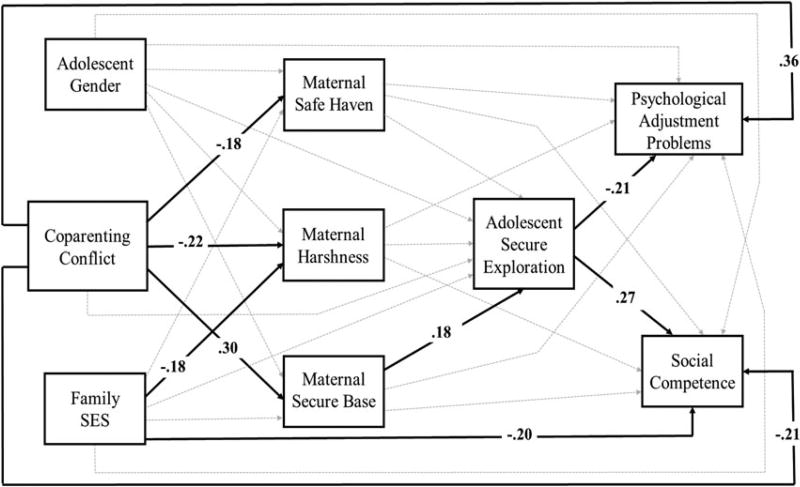

Testing adolescent exploration as a mediator

To test the second hypothesis, we again ran a path model, this time specifying adolescents’ secure exploration in the speech task at Wave 2 as a mediator between maternal parenting and the two forms of adolescent adjustment. The results of this model are shown in Figure 2. Again, all possible paths were included, resulting in a fully identified model. As with the first analysis, interparental coparenting conflict at Wave 1 continued to predict all three forms of maternal parenting in the support task: maternal harshness (β = 0.30, p < .01), safe haven (β = –0.18, p < .05), and secure base (β = –0.22, p < .01). Supporting an indirect effect through adolescent secure exploration, maternal secure base evidenced a significant, positive association (β = 0.18, p < .05). Adolescents’ secure exploration in the speech task, in turn, predicted contiguous parent reports of both adolescent greater social competence (β = 0.27, p < .01), and fewer psychological adjustment problems (β = –0.21, p < .01). As in the previous model, coparenting conflict continued to evidence a significant direct association with social competence and psychological adjustment (βs = –0.21 and 0.36, respectively) at Wave 2, although it was not directly linked to adolescents’ secure exploration in the speech task.

Figure 2.

A path model examining maternal safe haven, harshness, and secure base linking coparenting conflict with adolescent adjustment. All path coefficients are standardized values. Light-colored dotted lines indicate structural paths that were included in the model, but were not significant at p < .05.

The results of the path model suggest a possible chain of mediational processes from coparenting conflict in Wave 1 to maternal secure base, adolescent secure exploration, and ultimately adjustment in Wave 2 (Figure 3). To further examine this chain, bootstrapping tests were again performed using PRODCLIN. To test the first link, the indirect effect of interparental coparenting conflict on adolescent secure exploration through maternal secure base was significantly different from 0, 95% CI [−0.36, −0.01]. Then, proceeding to the second link, maternal secure base also evidenced an indirect effect on both social competence and psychological problems through adolescent secure exploration in the speech task, 95% CIs [0.01, 0.11] and [−0.17, −0.005], respectively.

Figure 3.

A path model testing adolescents’ secure exploration as an intervening factor linking maternal caregiving with adolescent adjustment in the overall process model of the consequences of coparenting conflict. All path coefficients are standardized values. Light-colored dotted lines indicate structural paths that were included in the model, but were not significant at p < .05.

Discussion

When parents struggle to negotiate their coparenting role, these disruptions present a potent risk for child and adolescent adjustment problems (Belsky, Putnam, & Crnic, 1996; Margolin et al., 2001). Of the many facets of coparenting, conflicts between parents around childrearing have been shown to be particularly insidious (Teubert & Pinquart, 2010). The current study sought to understand how and why coparenting conflicts undermine child adjustment. Guided by an attachment framework (George & Solomon, 2008; Grossman et al., 2008) and the spillover hypothesis (Erel & Burman, 1995; Sturge-Apple et al., 2006), the results provide a first step in testing a process model of the impact of coparenting disagreements for adolescent adjustment by simultaneously comparing multiple forms of maternal caregiving (i.e., safe haven and secure base supports) in shaping adolescents’ secure exploration. In line with our predictions, findings demonstrated unique associations between disruptions in coparenting and all three forms of maternal parenting in response to adolescents’ bids for support. This is consistent with the hypothesis that coparenting difficulties have a broad negative impact on many aspects of parenting. However, its relationship to adolescent adjustment was mediated selectively through mothers’ ability to provide secure base support. Secure base in turn was the only form of maternal parenting associated with adolescent adjustment. Tests further demonstrated that poor secure base support evidenced an indirect effect on adolescent adjustment, by undermining teens’ secure exploration. Together, these findings suggest that coparenting conflicts are an important source of contextual risk for social and psychological adjustment problems in adolescence, with the potential to disrupt the parent–adolescent attachment relationship.

Spillover from coparenting to parenting

The results are consistent with prior research supporting the spillover hypothesis, in which negativity in the coparenting relationship “spills over” into the parent–child relationship, increasing parental harshness and decreasing sensitivity (e.g., Feinberg et al., 2007; O’Leary & Vidair, 2005). However, the results also extend previous research by distinguishing between two forms of sensitive parenting: mothers’ attempts to relieve adolescents’ distress (i.e., safe haven) and encourage autonomous exploration (i.e., secure base). Consistent with expectations, parental safe haven and secure base represent related, but distinct aspects of caregiving (Collins & Feeney, 2004; George & Solomon, 2008). This distinction was further supported by the unique association between coparenting conflicts and each form of maternal caregiving. Moreover, the results suggest that mothers do not merely recapitulate hostility from the interparental subsystem in parent–child interactions. Conflicts around childrearing may impair mothers’ ability to sensitively recognize and respond to adolescents’ bids for support as well.

Several processes may account for the associations between coparenting conflict and maternal parenting. The stress of coping with coparenting conflicts may deplete mothers of the regulatory resources needed to effectively mobilize a sensitive caregiving response. For example, difficulties in coparenting may shake the foundation of support mothers rely on in meeting the challenges of parenting an adolescent while maintaining child-centered caregiving goals. This process could be explained by mothers’ heightened stress reactivity (e.g., adrenocortical activity; Sturge-Apple, Davies, Cicchetti, & Cummings, 2009) or by their concern for their marital partner’s support and availability (e.g., insecure romantic attachment; Davies, Sturge-Apple, Woitach, & Cummings, 2009), both of which have been shown to link interparental disturbances with parenting difficulties. Furthermore, parent cognitions may play an important explanatory role. Mothers with positive internal working models of themselves as caregivers are more confident and mindful in interactions with their child (George & Solomon, 2008; Moreira & Canavarro, 2015; Slade, Belsky, Aber, & Phelps, 1999). Coparenting conflict may signal to mothers that their partner lacks confidence in their ability to provide adequate care. If this then reduces mothers’ sense of efficacy in their parenting role, their ability to respond to adolescents’ bids for support may be weakened (Merrifield & Gamble, 2013; Schoppe-Sullivan, Settle, Lee, & Kamp Dush, 2016).

Although the findings provide support for the proposed process model, coparenting conflict continued to evidence a direct association with adolescent social and psychological adjustment. This is consistent with multiple conceptual frameworks predicting a direct effect of family conflict on child adjustment (e.g., Davies & Cummings, 1994; Davies & Martin, 2013; Grych & Fincham, 1990). For example, the reformulation of emotional security theory (Davies & Martin, 2013) suggests that exposure to hostile and destructive conflict between parents directly undermines children’s security in the interparental relationship. This direct effect is distinct from the indirect pathway through the parent–child attachment relationship (e.g., Sturge-Apple, Davies, Winter, Cummings, & Schermerhorn, 2008). As a separate, but related aspect of the interparental relationship, disagreements in the coparenting subsystem may similarly expose adolescents to interparental hostility, undermining teens’ sense of safety in the family (Sturge-Apple et al., 2006).

Specificity in the spillover process

Given prior evidence for specificity of parental sensitivity in supporting adolescent attachment security (e.g., Davidov & Grusec, 2005; McElwain & Booth-LaForce, 2006), we expected that detriments to maternal sensitivity due to the negative impact of coparenting conflicts would be particularly influential in undermining adolescent adjustment over and above maternal harshness. Although coparenting conflicts were negatively associated with all three aspects of parenting, results showed that only maternal secure base was linked with adolescent adjustment. When confronted with their adolescents’ bid for support, mothers who experienced more conflict in the coparenting relationship responded with little encouragement or unconditional support for their adolescents’ autonomous exploration. These mothers failed to express confidence in their adolescents’ ability to address the issue on their own, and this absence of secure base support was uniquely associated with poor adolescent social competence even over and above mothers’ harshness and safe haven support. This specificity contributes to a growing literature suggesting that each component of parental caregiving serves a unique and important function for child development (e.g., George & Solomon, 2008; Kerns et al., 2015). In addition, the results provide initial evidence for parental secure base support as a specific driver of the risk posed by coparenting difficulties.

Discussions of parenting from an attachment framework have argued that attachment security is most likely to develop when parents serve both as a base to explore and as a haven to return to in times of distress (Cassidy, Jones, & Shaver, 2013; George & Solomon, 2008). In support of this notion, examination of adolescents’ internal working models and attachment scripts show that secure teens are able to coherently articulate detailed memories of times in which their mothers served both of these functions (Dykas, Woodhouse, Cassidy, & Waters, 2006). Despite this, research on parental caregiving has focused most intently on parental safe haven support in promoting adolescent attachment security (i.e., Kerns et al., 2015). The results of this study, by contrast, highlight the potential unique effects of parental secure base support in early adolescence. In positing what may be unique about maternal secure base, we propose that mothers who are able to respond to their adolescents’ bids for support with this pattern of encouraging teens to push through distress and problem solve independently while being unconditionally accepting may be positioned to support their child’s attempts to meet a central developmental challenge of adolescence: establishing greater autonomy. Therefore, mothers’ failure to provide secure base support may be viewed by adolescents as less autonomy supportive at a time when this is a central goal. Moreover, in light of the previous findings suggesting that adolescents begin to prefer peers for safe haven, but continue to rely on mothers as secure base providers (e.g., Markiewicz et al., 2006), our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that adolescents may, themselves, be particularly open and receptive to maternal secure base support. In the context of burgeoning needs for greater autonomy and improving ability to self-regulate emotions, parents’ safe haven support may simply matter less for adolescents who are able to meet these needs elsewhere (e.g., with peers). Further research is needed to confirm whether interindividual differences in maternal secure base support may take on greater importance, over and above differences in maternal safe haven, for adolescents’ security in the parent–child attachment relationship and, ultimately, their adjustment.

Poor secure base support impedes secure exploration

In the next step of our process model, the results revealed that adolescents’ secure exploration helped to explain why mothers’ difficulties providing secure base support resulted in social and psychological impairments. Given previous work suggesting that social evaluation represents a stage-salient fear in early adolescence (e.g., Somerville, 2013), adolescents were observed while preparing and then giving a speech about themselves to later be evaluated. This presented adolescents with the challenge of overcoming the anxiety-provoking social component of the task in order to generate, plan, and perform the speech. Although prior research has used a similar task to assess adolescent functioning in an attachment-relevant context (e.g., Zimmerman et al., 2009), this is, to our knowledge, the first attempt to observe “secure exploration” in adolescence.

Moreover, the current study advanced the existing literature by demonstrating the unique association of maternal secure base, over and above safe haven and harshness, in promoting adolescents’ secure exploration. Adolescents whose mothers offered poor secure base support were less able to adequately regulate their emotions, assemble an appropriate response to the challenge, or use their mother for support in completing the speech task. Examination of the broader attachment literature suggests several mechanisms that may help to explain this association. For example, repeated experiences in which mothers provide secure base support may solidify into secure internal working models of attachment characterized by an underlying sense of confidence in parents’ availability and support as needed (Dykas et al., 2006; Kerns, Abraham, Schlegelmilch, & Morgan, 2007). As adolescents increasingly spend greater time without their parents present, this underlying confidence in parents’ availability may leave teens with greater emotional and cognitive resources available to invest in successfully meeting the developmental challenges of adolescence (Dykas & Cassidy, 2011; McElhaney et al., 2009). As another example, researchers have pointed to the importance of sensitive parenting for promoting adaptive coping and stress responses when adolescents are faced with subsequent challenges (Kobak, Cassidy, Lyons-Ruth, & Ziv, 2005; Spangler & Zimmerman, 2014). Although effective safe haven behaviors might appear to be the logical parental source of regulatory support, in the context of adolescents’ growing emotion regulation capacities parents’ ability to push adolescents to persist in the face of mild stressors may be providing a developmentally appropriate opportunities to test and refine these capabilities.

Secure exploration, in turn, explained the indirect effect linking maternal secure base and adolescents’ psychological and social adjustment. As a behavioral marker for attachment security (Grossman et al., 2008; McElhaney et al., 2009), secure exploration was reflected in an overarching pattern whereby adolescents were able to (a) modulate their emotions to promote engagement in the task; (b) approach the exploratory challenge with persistence, flexibility, and resourcefulness; and (c) balance this agency by freely seeking assistance from their mother as needed. The concept of a balance between attachment and exploratory goals harkens back to early attachment theory (e.g., Bowlby 1969). Healthy development requires the child to balance appropriate fears (i.e., safety) while also engaging and mastering new environments and skills (i.e., exploration). Secure exploration therefore provides a distinction between pure independence (i.e., dismissing the attachment figure) from autonomy that is facilitated by cooperative partnership between the adolescent and the attachment figure (Allen et al., 2003; Grossman et al., 2008). Although no studies to date have explicitly observed secure exploration in adolescence, prior studies have shown that a parent–adolescent relationship characterized by a balance of autonomy and relatedness predicts healthy psychological adjustment across a range of indices (Allen et al., 2002; Allen, Porter, McFarland, McElhaney, & Marsh, 2007).

We propose that secure exploration, as assessed in the current study, represents a behavioral expression of attachment security that marks adolescents’ competency in meeting novel socioemotional challenges. Developmental psychopathology models emphasize the importance of successfully completing stage-salient developmental tasks in promoting children’s adaptation across domains (e.g., Cicchetti, 1993; Sroufe, 2005). As children enter adolescence, they are presented with new challenges, such as forming close friendships, navigating increasingly complex peer relationships, and establishing their identity. When their underlying confidence in their parents’ availability is shaken, perhaps by repeated experiences in which parents fail to provide secure base support, concerns for security deplete adolescents’ of important psychological resources needed to adapt to these developmental challenges (Allen, 2008; McElhaney et al., 2009). Ultimately, these difficulties set the stage for maladaptive adjustment across domains.

Limitations and future directions

Together, these findings support our proposed process model (Figure 1), in which disruptions in the coparenting relationship spillover to undermine parenting in the attachment domain (Path a). Poor secure base was in turn associated with less adolescent secure exploration (Path b2), which in turn served to explain the indirect link between mothers’ secure base and adolescent’s social and psychological adjustment (Path c). However, interpretation of the results must be considered in light of several study limitations. First, our sample consisted of predominantly white, middle-class, two-parent families. Caution should be exercised in applying these findings to other types of families. Second, although this was a two-wave multimethod study, that each assessment was only available at one time point precludes us from making strong conclusions regarding the directionality of the findings. Based on the extensive literature suggesting that disruptions in the coparenting relationship pose a risk for child adjustment problems by undermining parenting (e.g., Teubert & Pinqart, 2010), we focused on a similar pattern here. However, researchers have also found evidence for reciprocal associations between child adjustment difficulties and coparenting and between parent–child and interparental relationships (Cox & Paley, 1997; Cui, Donnellan, & Conger, 2007). Therefore, alternative models are possible. Examining these processes within a longitudinal model equipped to test for change is a critical next step.

Third, our assessments of parenting only included mothers. Although research on the caregiving system in fathers or adolescents is limited, there is evidence to suggest that mothers and fathers may serve different roles in providing safe haven and secure base support for children (Grossman et al., 2008; Kerns et al., 2015). The results of the current study seem to suggest that mothers are important sources of secure base, at least in adolescence, and this is corroborated by prior research suggesting that adolescents continue to turn to their mothers for secure base support over fathers, and best friends (Markiewicz et al., 2006; Nickerson & Nagle, 2005). However, future research should directly examine and compare parenting across mothers and fathers to provide a more complete picture of the caregiving context in adolescence. The association between coparenting conflict and parenting may differ for mothers and fathers as well. For example, fathers’ parenting was found to be more susceptible to conflict in the interparental relationship, including conflict over childrearing, in studies of families with young children (Brown et al., 2010; Davies et al., 2009; Holland & McElwain, 2013).

Fourth, although this study represents an advancement over the previous literature regarding the consequences of disruptions in the coparenting relationship, our parent-report assessment of coparenting conflict did not provide a nuanced picture of the interparental dynamics involved. Parents reported on their disagreements across multiple aspects of childrearing, including being too lenient and being too strict. Future research may benefit from providing a more complete assessment of this construct, in order to figure out whether and how different configurations of coparenting disruptions may be more or less problematic for parental caregiving. For example, our assessment of coparenting conflict did not provide enough information to determine whether fathers viewed mothers as being too strict with their adolescent or vice versa. Potentially, different configurations of coparenting conflict may pose unique problems for each parents’ interactions with their adolescent (Erel & Burman, 1995; Pedro, Ribeiro, & Shelton, 2012). Further advancing our goal of developing a more comprehensive and process-oriented understanding of the role of interparental coparenting conflict in shaping family dynamics and adolescent adjustment will require a more nuanced understanding of the nature of these disagreements.

Translational implications

Recently, studies have begun to demonstrate the efficacy of attachment-based therapeutic interventions tailored specifically for adolescents and their parents (e.g., Kobak & Kerig, 2015). Each of these programs seeks to reduce adolescent problems by improving the quality of the caregiving environment. Several programs (e.g., Dozier & Roben, 2015; Moretti & Obsuth, 2009) share a common focus on parenting as a primary force for change. The results thus far have been promising, demonstrating positive effects for attachment-based therapy in families coping with adolescent depression (Diamond, Diamond, & Levy, 2014), suicidality (Diamond et al., 2010), aggression (Moretti & Obsuth, 2009; Moretti, Obsuth, Mayseless, & Scharf, 2012), and incarceration (Keiley, 2002). However, there remains a need for better understanding of the precise mechanisms of effect (Kobak & Kerig, 2015; Moretti, Obsuth, Craig, & Bartolo, 2015).

Although firm conclusions will require replication, the results of this study have some translational implications. First, the findings confirm the importance of considering spillover processes across multiple family subsystems in characterizing the family contexts that ultimately support or undermine adolescent adjustment. That conflict in the coparenting relationship served to undermine multiple aspects of maternal parenting, even in the face of adolescents’ bids for support, suggests that fostering a quality coparenting relationship may disrupt or even prevent this pathogenic cascade. Consistent with this notion, prior research suggests that adult romantic relationships serve as the training ground for the development of a sensitive and well-developed caregiving system (Collins & Ford, 2010; Davies et al., 2009). Moreover, psychosocial prevention programs designed to strengthen the coparenting relationship have had positive effects for both parenting and child functioning during the transition to parenthood (Feinberg et al., 2016; Feinberg & Kan, 2008). Failing to take into account toxic interparental dynamics could sustain dysfunctional parenting even in the face of an otherwise effective treatment approach. Second, the unique role of maternal secure base in promoting secure exploration and supporting healthy adjustment may offer a precise target for clinical intervention. Improving parental sensitivity is a central component to many attachment-based interventions, with both children and teens (Bakersman-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, 2005; Kobak, Zajac, Herres, & Krauthamer Ewing, 2015). This study suggests that there may be value in moving beyond global conceptualizations of sensitive parenting and toward a better understanding of the specific behaviors that are most important in promoting adolescent wellness.

Conclusion

Despite limitations, this study broke new ground in several ways. This was the first study to compare multiple aspects of parenting in mediating the link between coparenting difficulties and adolescent social and psychological adjustment. Drawing on the behavioral systems perspective, we introduced a new method for assessing parental caregiving using observations of parent–adolescent interactions in a support-seeking context. The unique role of maternal secure base support in this process model contributes to the growing literature aimed at improving specificity in the definition of parental sensitivity. Moreover, this was the first study to include an observational assessment of adolescent secure exploration as a developmental outgrowth of the exploratory system in infancy. Ultimately, the results represent an initial step toward understanding the unfolding consequences of interparental coparenting conflict for adolescents.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant 5R01HD06078905 (to M.L.S.-A. and P.T.D.). We are grateful to the teens and parents who participated in this project. Our gratitude is expressed to the staff on the project and the graduate and undergraduate students at the University of Rochester.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: An integrated multi-informant assessment. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Bell SM. Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development. 1970;41:49–67. doi: 10.2307/1127388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Bell SM, Stayton DJ. Infant-mother attachment and social development: “Socialization” as a product of reciprocal responsiveness to signals. In: Richards PM, editor. The integration of a child into a social world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1974. pp. 99–135. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP. The attachment system in adolescence. In: Cassidy Js, Shaver PR., editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 419–435. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Marsh P, McFarland C, McElhaney KB, Land DJ, Jodl KM, Peck S. Attachment and autonomy as predictors of the development of social skills and delinquency during midadolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:56–66. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, McElhaney KB, Land DJ, Kuperminc GP, Moore CW, O’Beirne-Kelly H, Kilmer SL. A secure base in adolescence: Markers of attachment security in the mother-adolescent relationship. Child Development. 2003;74:292–307. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Miga EM. Attachment in adolescence: A move to the level of emotion regulation. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2010;27:181–190. doi: 10.1177/0265407509360898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Porter M, McFarland C, McElhaney KB, Marsh P. The relation of attachment security to adolescents’ paternal and peer relationships, depression, and externalizing behavior. Child Development. 2007;78:1222–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01062.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F. Less is more: Meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:195–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F. Disorganized infant attachment and preventative interventions: A review and meta-analysis. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2005;26:191–216. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Mesman J, Alink LR, Juffer F. Effects of an attachment-based intervention on daily cortisol moderated by dopamine receptor D4: A randomized control trial on 1- to 3-year-olds screened for externalizing behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:805–820. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, editor. Intrusive parenting: How psychological control affects children and adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Beijersbergen MD, Juffer F, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzen-doorn MH. Remaining or becoming secure: Parental sensitive support predicts attachment continuity from infancy to adolescence in a longitudinal adoption study. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48:1277–1282. doi: 10.1037/a0027442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Putnam S, Crnic K. Coparenting, parenting, and early emotional development. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 1996;74:45–55. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219967405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth-LaForce C, Groh AM, Burchinal MR, Roisman GI, Owen MT, Cox MJ. Caregiving and contextual sources of continuity and change in attachment security from infancy to late adolescence. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2014;79(3, Serial No. 314):67–84. doi: 10.1111/mono.12114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GL, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Mangelsdorf SC, Neff C. Observed and reported supportive coparenting as predictors of infant-mother and infant-father attachment security. Early Child Development and Care. 2010;180:121–137. doi: 10.1080/03004430903415015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, Benson MJ, Gerard JM. Interparental hostility and early adolescent problem behavior: The mediating role of specific aspects of parenting. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:265–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00132.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caldera YM, Lindsey EW. Coparenting, mother-infant interaction, and infant-parent attachment relationships in two-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:275–283. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Jones JD, Shaver PR. Contributions of attachment theory and research: A framework for future research, translation, and policy. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25:1415–1434. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Johnston C. Interparent childrearing disagreement, but not dissimilarity, predicts child problems after controlling for parenting effectiveness. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41:189–201. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.651997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. Developmental psychopathology: Reactions, reflections, projections. Developmental Review. 1993;13:471–502. doi: 10.1006/drev.1993.1021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Feeney BC. Working models of attachment shape perceptions of social support: Evidence from experimental and observational studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:363–383. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Ford MB. Responding to the needs of others: The caregiving behavioral system in intimate relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2010;27:235–244. doi: 10.1177/0265407509360907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ge X, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development. 1994;65:541–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B. Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:243–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Donnellan MB, Conger RD. Reciprocal influences between parents’ marital problems and adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1544–1552. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Davidov M, Grusec JE. Untangling the links of parental responsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Development. 2006;77:44–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT. Children’s Reactions to Interparental Disagreements (CRID) coding system. University of Rochester; 2015. Unpublished coding manual. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Manning LG, Cicchetti D. Tracing the cascade of children’s insecurity in the interparental relationship: The role of stage-salient tasks. Child Development. 2013;84:297–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01844.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Martin MJ. The reformulation of emotional security theory: The role of children’s social defense in developmental psycho-pathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25:1435–1454. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML, Woitach MJ, Cummings EM. A process analysis of the transmission of distress from interparental conflict to parenting: Adult relationship security as an explanatory mechanism. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1761–1773. doi: 10.1037/a0016426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wolff MS, van IJzendoorn MH. Sensitivity and attachment: A meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Development. 1997;68:571–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb04218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond GS, Diamond GM, Levy SA. Attachment-based family therapy for depressed adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond GS, Wintersteen MB, Brown GK, Diamond GM, Gallop R, Shelef K, Levy S. Attachment-based family therapy for adolescents with suicidal ideation: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey S, Forehand R, Brody G. Coparenting conflict and parenting behavior in economically disadvantaged single parent African American families: The role of maternal psychological distress. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:621–630. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9114-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Roben CK. Attachment-related preventive interventions. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and research: New directions and emerging themes. New York: Guilford Press; 2015. pp. 374–392. [Google Scholar]

- Dykas MJ, Cassidy J. Attachment and the processing of social information across the life span: Theory and evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137:19–46. doi: 10.1037/a0021367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykas MJ, Woodhouse SS, Cassidy J, Waters HS. Narrative assessment of attachment representations: Links between secure base scripts and adolescent attachment. Attachment& Human Development. 2006;8:221–240. doi: 10.1080/14616730600856099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. The impact of nonnormality on full information maximum-likelihood estimation for structural equation models with missing data. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:352–370. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.6.4.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]