Abstract

Background

To compare the efficacy and toxicity of anti-programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) versus docetaxel in previously treated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Materials and methods

Phase III randomised clinical trials (RCTs) were identified after systematic review of databases and conference proceedings. A random-effect model was used to determine the pooled HR for overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS) and duration of response. The pooled OR for overall response and treatment-related side effects were calculated using the inverse-variance method. Heterogeneity was measured using the τ2 and I2 statistics.

Results

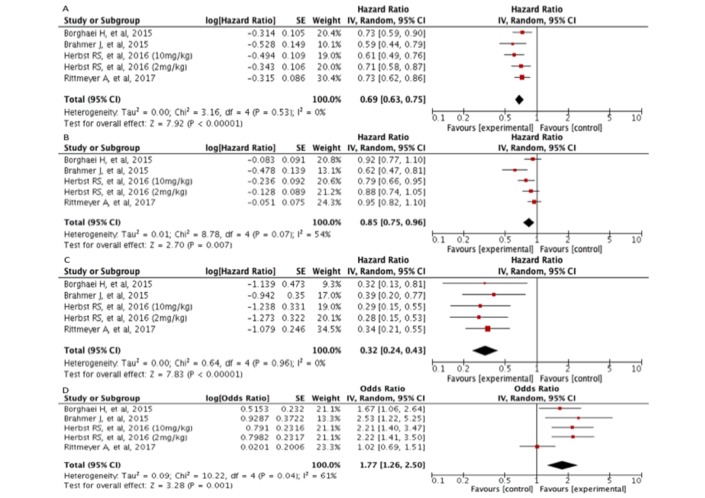

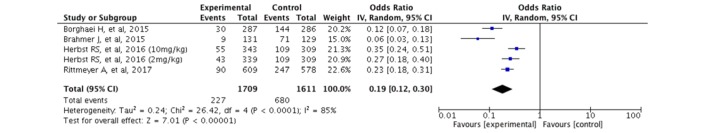

After the systematic review, we included four phase III RCTs (n=2737) in this meta-analysis. The use of anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 agents (atezolizumab, nivolumab and pembrolizumab) was associated with better OS in comparison with docetaxel alone (HR: 0.69; 95% CI 0.63 to 0.75; p<0.00001). Similarly, the PFS and duration of response was significantly longer for patients receiving immunotherapy (HR: 0.85; 95% CI 0.75 to 0.96; p=0.007 and HR:0.32; 95% CI 0.24 to 0.43; p<0.00001, respectively) versus single agent chemotherapy. The overall response rate was also higher for patients who received any anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 therapy in comparison with docetaxel (OR: 1.77; 95% CI 1.26 to 2.50; p=0.001). Regarding treatment-related side effects grade 3 or higher, patients who received immunotherapy experienced less events than patients allocated to docetaxel (OR: 0.19; 95% CI 0.12 to 0.30; p<0.00001)

Conclusion

The use of anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 therapy in patients with progressive advanced NSCLC is significantly better than the use of docetaxel in terms of OS, PFS, duration of response and overall response rate.

Keywords: non-small-cell lung cancer, atezolizumab, pembrolizumab, nivolumab, meta-analysis

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Recent trials have acknowledged the survival benefit of checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced and progressive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

What does this study add?

This systematic review and meta-analysis resumes the available data on immunotherapy from randomised clinical trials and summarises the overall efficacy and safety of anti-programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1)/anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) agents.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Our findings supports the current clinical evidence regarding the overall survival benefit derived from anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 agents in comparison with docetaxel for previously treated patients with advanced NSCLC.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, estimated to be responsible of 1.59 millions deaths in 2012.1 2 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 85% of cases, and the majority of patients are diagnosed with locally advanced or metastatic disease.3 Despite the significant therapeutic advances with the introduction of molecularly targeted therapies, antiangiogenics and new chemotherapeutic agents, the prognosis of the majority of these patients is still poor.1 Relapses are frequent after first-line chemotherapy or molecular-targeted agents against epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 and anaplastic lymphoma kinase fusion gene (EML4-alk), and most patients will not experience sustained disease control with second-line agents.4 For relapsing patients, docetaxel was approved as a second-line treatment based on two phase III trials.5

It has been recently acknowledged that cancer cells can induce immune tolerance in the tumour microenvironment by blocking coinhibitory signals of cytotoxic T-cells, also known as immune checkpoints.6 The programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1)/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) interaction inhibits T-cell response, promotes differentiation of CD4 T cells into T regulatory cells, induces apoptosis of tumour-specific T cells and causes T cell resistance.6 Besides, cancer cells can also change the tumour microenvironment to induce an immunosuppressive state through expression of inhibitory cytokines and recruitment of regulatory T lymphocytes and myeloid-derived suppressor cells.7

Antibodies against PD-1 (nivolumab and pembrolizumab) and PD-L1 (atezolizumab) have demonstrated activity against chemotherapy-refractory NSCLC tumours in several phase III trials.8–11 These recent trials have questioned the paradigm of treatment for previously treated metastatic NSCLC. For this reason, we aimed to determine the overall efficacy and safety of these agents versus docetaxel.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and study selection

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement for reporting systematic reviews was followed (checklist available as online supplementary file 1).12 First, four authors (AR-E, AvdL, MJ and RR-V) independently scrutinised the titles and abstracts retrieved by a search strategy in electronic databases (MEDLINE, Embase and The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) from May 2007 to 1 May 2017 (online supplementary file 2). The search was done in May 2017. Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer World Conference on Lung Cancer annual meeting and European Society of Medical Oncology annual meeting were also searched from 2012 to 2017 for relevant abstracts. In case of reports of the same trial, we included only the most recent results (corresponding to longer follow-up). Then, the authors examined full-text articles of potential eligible studies according to the eligibility criteria. Disagreements were resolved in discussion with another author (LC-R). Data extraction tables were designed specifically for this review to aid data collection. Data from relevant studies were extracted and included information on trial design, participants, interventions and outcomes.

esmoopen-2017-000236supp001.jpg (57.8KB, jpg)

esmoopen-2017-000236supp002.jpg (41.6KB, jpg)

Eligibility criteria

We decided to include published and unpublished phase III randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that enrolled patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). We included the reported comparisons of chemotherapy versus any anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 agent used as monotherapy. We excluded trials with incomplete data and those studies published in non-English languages. In case of finding a trial with more than two comparisons, we decided to count each intervention separately.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was overall survival (OS), calculated from the date of randomisation to the date of death. Secondary outcomes included: (1) progression-free survival (PFS): defined by the RECIST 1.1. criteria13; (2) objective response rate: defined as the percentage of patients with complete or partial response as per RECIST 1.1; and (3) duration of response, defined as time from first evidence of partial and complete response until disease progression or death.

We also evaluated the safety of each drug in all patients who received at least one dose of the study treatment. Adverse drug reactions were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0.

Quality assessment

The risk of bias was evaluated by three reviewers using the Cochrane Collaboration Tool,12 including: sufficient sequence generation, adequate allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data addressed and freedom from selective reporting. Publication bias was visually examined in a funnel plot. The risk of bias was categorised as ‘low risk’, ‘high risk’ or ‘unclear risk’.

Data collection and statistical analysis

For time-to-event outcomes, the treatment efficacy was measured using the HR with its corresponding 95% CI. For the association of the risk of overall response, we employed the OR and its corresponding 95% CI. We used a random-effect model for the efficacy measures according to the DerSimonian-Laird method. The pooled HR and pooled risk ratio were calculated according to the inverse-variance method, as described by Parmar et al.14

Heterogeneity was determined by the τ2 and I2 statistics. Data analysis was performed using RevMan V.5.3 software.

Results

Study selection

Through the search strategy, we identified four trials8–11 that enrolled 2737 patients with progressive disease for advanced non-small cell lung cancer who were treated with an anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 antibody or docetaxel (the PRISMA flow diagram for study inclusion is available as online supplementary file S1).

Description of studies and patients

Table 1 resumes the main characteristics of each trial. One trial explored the effect of pembrolizumab in two different doses. Therefore, we show the results for each specific dose. The primary outcome was OS in all trials. Of note, the majority of patients had wild-type EGFR non-squamous NSCLC. All patients had measurable disease per RECIST 1.1 criteria.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the included trials

| First author (trial) | Rittmeyer et al

(OAK)9 |

Herbst et al

(KEYNOTE-010)8 |

Borghaei et al (CheckMate 057)11 | Brahmer et al

(CheckMate 017)10 |

| Immunotherapy | Atezolizumab | Pembrolizumab | Nivolumab | Nivolumab |

| Patient’s characteristics and definition of treatment | ||||

| Median age (years) (range) | 64.0 (30–85) | 62.66 (56-69) | 62 (21–85) | 63 (39–85) |

| Disease stage (n (%)) | IIIB and IV (non-specified) | Advanced (non-specified) | IIIB: 44 (8) IV: 538 (92) |

IIIB: 53 (19) IV: 217 (80) Not reported: 2 (1) |

| Performance status (n (%)) | ECOG 0: 315 (37) ECOG 1: 535 (63) |

ECOG 0: 49 (32) ECOG 1: 102 (67) ECOG 2: 1 (1) |

ECOG 0: 179 (31) ECOG 1: 402 (69) Unknown: 1 (<1) |

ECOG 0: 64 (24) ECOG 1: 206 (76) Unknown: 1 (<1) |

| Histology (n (%)) | Non-squamous: 628 (74) Squamous: 222 (26) |

Non-squamous: 724 (70.1) Squamous: 222 (21.5) Other: 25 (2.4) Unknown: 62 (6.0) |

Non-squamous: 582 (100) | Squamous: 272 (100) |

| EGFR mutation negative (n (%)) | 628 (74) | 875 (84.70) | 500 (86) | Not reported |

| EGFR mutant (n (%)) | 85 (10) Unknown: 137 (16) |

86 (8.32) Unknown: 72 (6.96) |

82 (14) | Not reported |

| Positive ALK translocation (n (%)) | 2 (<1) | 8 (<1) | 21 (4) | Not reported |

| Positive KRAS mutation (n (%)) | 59 (7) | Not reported | 62 (11) | Not reported |

| Previous treatment | Chemotherapy: 1011 (97.9) Immunotherapy: 4 (<1) EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor: 143 (13.8) ALK inhibitor: 10 (<1) |

Chemotherapy: 1011 (86.5) Immunotherapy: 4 (<1) EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor: 143 (12.24) ALK inhibitor: 10 (<1) |

Platinum-based therapy: 582 (100) EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor: 53 (9) ALK inhibitor: 3 (1) |

Platinum duplet chemotherapy: (Paclitaxel 34%, gemcitabine 44%, etoposide 13%) EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor: 3 (1) |

| Inclusion criteria | Older than 18 years. Measurable disease per RECIST 1.1. One or more previous cytotoxic chemotherapy, including platinum-based chemotherapy or previous use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

Older than 18 years. Progression after two or more cycles of platinum-doublet chemotherapy or tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Measurable disease per RECIST 1.1. PD-L1 expression on at least 1% of tumour cells |

Older than 18 years. Documented IIIB or IV disease or recurrent non-squamous NSCLC after radiation therapy or surgical resection. Disease recurrence or progression during or after one prior platinum-based doublet chemotherapy regimen. EGFR mutation or ALK translocation allowed to have received or be receiving an additional line of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy and a continuation of or switch to maintenance therapy with pemetrexed, bevacizumab or erlotinib |

Older than 18 years. Disease recurrence after one prior platinum-containing regimen in squamous NSCLC. Prior maintenance therapy including an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor was allowed. |

| Exclusion criteria | Autoimmune diseases. Previous treatment with docetaxel or therapies targeting the PD-L1 and PD-1 pathway. | Autoimmune disease requiring systemic steroids. Previous treatment with PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors or docetaxel. Known active brain metastases or carcinomatous meningitis. Active interstitial lung disease or history of pneumonitis requiring systemic steroids. |

Autoimmune disease Symptomatic interstitial lung disease Systemic immunosuppression. Prior therapy with T cell costimulation or checkpoint targeted agents or prior docetaxel therapy. |

Autoimmune disease Symptomatic interstitial lung disease Systemic immunosuppression. Prior therapy with T cell costimulation or checkpoint targeted agents or prior docetaxel therapy. |

| Immunotherapy dose | 1200 mg intravenous every 3 weeks | 2 mg/kg intravenous every 3 weeks. 10 mg/kg intravenous every 3 weeks |

3 mg/kg every 2 weeks | 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks |

| Docetaxel dose | 75 mg/m2 intravenous every 3 weeks | 75 mg/m2 intravenous every 3 weeks | 75 mg/m2 intravenous every 3 weeks | 75 mg/m2 intravenous every 3 weeks |

| PD-L1 staining subgroups/antibody clone and method (n (%)) | 1% or less: 379 (45) >1%: 463 (54) >5%: 265 (31) >50%: 137 (16) SP-142 (Ventana Medical Systems, Oro Valley, Arizona, USA) |

1%–49%: 591 (57.2) ≥50%: 442 (42.8) 22C3 (Dako, Carpinteria California, USA) |

<1%: 209 (36.0) >1%: 246 (42.3) Not quantifiable: 127 (21.7) 28–8 (Dako) |

<1%: 106 (39.0) >1%: 119 (43.7) Not quantifiable: 47 (17.3) 28–8 Dako |

| Number of previous lines for advanced disease (n (%)) | 1: 640 (75) 2: 201 (25) |

1: 713 (69.02) 2: 210 (20.32) ≥3: 90 (8.71) Unknown: 2 (<1) |

1: 515 (88) 2: 66 (11) 3: 1 (<1) |

1: 271 (99) 2: 1 (1) |

| Enrolment time and sample size | From March 2011 to November 2014. n=850 |

From August 2013 to February 2015. n=1033. |

From November 2012 to December 2013. n=582 | From October 2012 to December 2013. n=272 |

| Primary end point | Overall survival | Overall survival and progression-free survival | Overall survival | Overall survival |

| Secondary end points | Progression-free survival. Proportion of patients who had an objective response. Duration of response Safety |

Response rate Duration of response Safety |

Objective response rate Progression-free survival Patient-reported outcomes |

Objective response rate Progression-free survival Patient-reported outcomes |

ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase gene; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; KRAS, K-ras gene; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PD-1, programmed cell death receptor 1; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1.

Outcomes

Table 2 summarises the main outcomes of each trial.

Table 2.

Overall results of the included trials

| First author | Rittmeyer et al

(OAK)9 |

Herbst et al

(KEYNOTE-010)8 |

Borghaei et al (CheckMate 057)11 | Brahmer et al

(CheckMate 017)10 |

| Immunotherapy | Atezolizumab | Pembrolizumab | Nivolumab | Nivolumab |

| Number of patients on immunotherapy (experimental group) | 425 | 690 (2 mg/kg=344, 10 mg/kg=346) |

292 | 135 |

| Number of patients on chemotherapy (control group) |

425 | 343 | 290 | 137 |

| Follow-up (months) | 21 (median) | 13.1 (median) | 13.1 (minimum) | 11.0 (minimum) |

| Median number of chemotherapy cycles | 2.1 months | 2.0 months (0.8–3.6) | Four cycles (range: 1–23) | Three cycles (range: 1–29) |

| Overall survival (OS) | Events: Atezolizumab: 271 Docetaxel: 298 Median OS: 13.8 months (experimental) versus 9.6 months (docetaxel) HR=0.73 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.87) p=0.0003 |

Events: Pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg: 172 Pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg: 156 Docetaxel: 193 Median OS: 10.4 months (pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg), 12.7 months (pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg) versus 8.5 months (docetaxel) HR for pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg versus docetaxel=0.71 (95% CI 0.58 to 0.88) p=0.0008) HR for pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg versus docetaxel=0.61 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.75) p<0.0001 |

Events: Nivolumab: 190 Docetaxel: 223 Median OS: 12.2 months (experimental) versus 9.4 months (docetaxel) HR=0.73 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.89) p=0.002 |

Events: Nivolumab: 86 Docetaxel: 113 Median OS: 9.2 months (experimental) versus 6.0 months (docetaxel) HR=0.59 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.79) p<0.001 |

| Progression-free survival (PFS) | Events: Not reported Median PFS: 2.8 months (experimental) versus 4.0 months (docetaxel) HR=0.95 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.10) p=0.493 |

Events: Experimental: Pembrolizumab (2 mg/kg): 266 Pembrolizumab (10 mg/kg): 254 Docetaxel: 256 Median PFS: 3.9 months (pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg), 4.0 months (pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg) versus 4.0 months in the docetaxel group HR=0.88 for pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg versus docetaxel (95% CI 0.74 to 1.05) p=0.07: HR=0.79 for pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg versus docetaxel (95% CI 0.66 to 0.94) p=0.004 |

Events: Experimental: 234 Docetaxel: 245 Median PFS: 2.3 months (nivolumab) versus 4.2 months (docetaxel) HR=0.92 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.10) p=0.39 |

Events: Experimental: 105 Docetaxel: 122 Median PFS: 3.5 months (experimental) versus 2.8 months (docetaxel) HR=0.62 (95% CI 0.47 to 0.81) p<0.001 |

| Overall response rate (n (%)) | Experimental: 58 (14) Docetaxel: 57 (13) |

Experimental: 62 (18). p=0.0005 for 2 mg/kg. 64 (18). p=0.0002 for 10 mg/kg Docetaxel: 32 (9) |

Experimental: 56 (19) Docetaxel: 36 (12) |

Experimental: 27 (20%) Docetaxel: 12 (9%). |

| Duration of response | Median: 16.3 months (atezolizumab) versus 6.2 months (docetaxel) HR=0.34 (95% CI 0.21 to 0.55) p<0.00001 |

Median: not reached (both doses of pembrolizumab) versus 8 months (docetaxel). HR*=0.28 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.53) For pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg versus docetaxel, p<0.0001 HR*:0.29 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.55) For pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg versus docetaxel, p<0.0001 |

Median: 17.2 months (nivolumab) versus 5.6 months (docetaxel) HR*=0.32 (95% CI 0.13 to 0.83) p=0.02 |

Median: Not reached (nivolumab) versus 8.4 months (docetaxel) HR*=0.39 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.79) p=0.008 |

| Treatment-related adverse event (grades III–V) (n (%)) | Atezolizumab: 90 (15): Fatigue 17 (2.8) Dyspnoea: 15 (2.5) Anaemia: 14 (2.3) Docetaxel: 247 (43): Neutropaenia: 75 (13). Febrile neutropaenia: 62 (10.7) Anaemia: 33 (5.7) |

Pembrolizumab: 2 mg/kg: 43 (13) 10 mg/kg: 55 (16): Fatigue: 2 mg/kg: 4 (1) 10 mg/kg: 6 (2) Pneumonitis: 2 mg/kg: 7 (2) 10 mg/kg: 7 (2) Severe skin reactions: 2 mg/kg: 3 (1) 10 mg/kg: 6 (2) Docetaxel: 109 (35): Fatigue: 11 (4) Diarrhoea: 7 (2) Asthenia: 6 (2) Anaemia: 5 (2) Neutropaenia: 38 (12) |

Nivolumab: 30 (10): Fatigue: 3 (1) Nausea: 2 (1) Diarrhoea: 2 (1) Docetaxel: 144 (54): Neutropaenia: 83 (31) Febrile neutropaenia: 26 (10) Leucopaenia: 22 (8) |

Nivolumab: 9 (7): Fatigue: 1 (1) Decrease appetite: 1 (1) Leucopaenia: 1 (1) Docetaxel: 71 (55): Neutropaenia: 38 (30) Febrile neutropaenia: 13 (10) Fatigue: 10 (8) |

| Discontinuation rate (n (%)) | Atezolizumab: 46 (8) Docetaxel: 108 (19) |

Pembrolizumab (2 mg/kg): 15 (4) Pembrolizumab (10 mg/kg): 17 (5) Docetaxel: 31 (10) |

Nivolumab: (5) Docetaxel: (15) |

Nivolumab: (3) Docetaxel: (10) |

*Calculated from data.

Overall survival

As shown in table 2 and figure 1A, there was an OS improvement of anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 therapy in comparison with docetaxel (pooled HR=069; 95% CI 0.63 to 0.75). There was no evidence of significant heterogeneity among the included trials regarding this outcome (τ2: 0.00; I2: 0%; p=0.53).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of HRs for overall survival (A), progression-free survival (B), duration of response (C) and ORs for overall response (D).

Progression-free survival

Patients with immunotherapy experienced less progression events than those patients receiving docetaxel (pooled HR: 0.85; 95% CI 0.75 to 0.96). There was evidence of moderate heterogeneity among the included trials for this specific outcome (τ2: 0.01; I2: 54%; p=0.07) (figure 1B).

Duration of response

The duration of response was significantly longer for patients receiving immunotherapy in comparison to docetaxel (pooled HR: 0.32; 95% CI 0.24 to 0.43). For this outcome we detected no significant heterogeneity (τ2: 0.00; I2: 0%; p=0.96) (figure 1C).

Overall response

The odds of overall response significantly increased with use of anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 therapy versus docetaxel alone (pooled OR: 1.77; 95% CI 1.26 to 2.50). There was significant heterogeneity found among the included trials (τ2: 0.09; I2: 61%; p=0.04) (figure 1D).

Treatment-related side effects

Regarding adverse drug reactions grade 3 or higher, use of docetaxel significantly increased the burden of therapy, with 42.2% of patients experiencing any treatment-related side effect, particularly neutropaenia and febrile neutropaenia (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of ORs for treatment-related side effects.

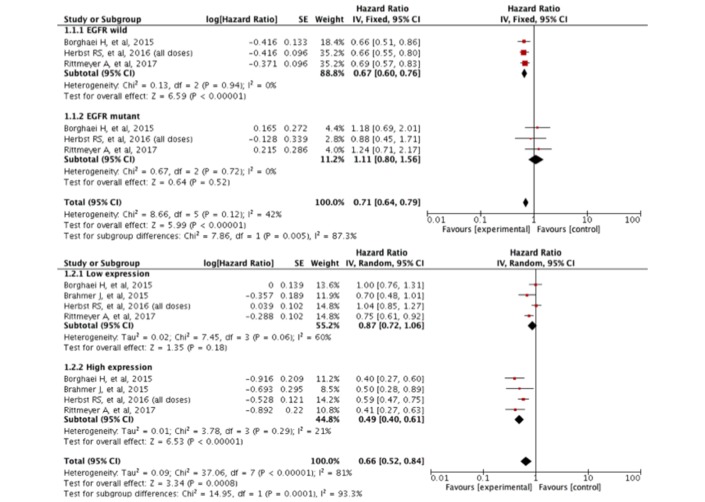

Subgroup analyses

Figure 3 shows the OS assessment according to EGFR mutation status and PD-L1 expression. We found heterogeneity between these two groups. Patients with wild-type EGFR were more likely to obtain an OS benefit from immunotherapy in contrast to patients with any EGFR mutation (p=0.005). Similarly, patients with high PD-L1 expression on immunohistochemistry had better OS than their counterparts (p=0.0001). Of note, the definition of high PD-L1 expression varied in each trial.

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis of OS according to EGFR mutation status and PD-L1 expression. EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; OS, overall survival; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias assessment is presented as online supplementary file S2. All included trials were open-label with high risk of performance and detection bias. Selection bias was likely to occur in one trial due to unmask allocation.9 We did not detect evidence of substantial publication bias in the funnel plot analysis (online supplementary file S3).

esmoopen-2017-000236supp003.jpg (18.9KB, jpg)

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis resumes the available data from published phase III RCT regarding the OS benefit of anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 agents versus docetaxel in patients with progressive advanced NSCLC. In summary, patients receiving these checkpoint inhibitors live longer and had better responses than patients allocated to docetaxel. Although this meta-analysis includes three different drugs with similar mechanism of action (atezolizumab, nivolumab and pembrolizumab), we did not detect any significant heterogeneity in the OS assessment. However, these trials share some differences in the inclusion criteria. Specifically, the KEYNOTE-010 trial included patients with a cut-off of at least 1% PD-L1 positive staining.8 In contrast, use of atezolizumab and nivolumab was associated with an OS improvement regardless of the PD-L1 status.9–11 Besides, the OAK Trial allowed the inclusion of patients with PD-L1 expression on tumour cells or tumour-infiltrating immune cells.9 It has been previously demonstrated that PD-L1 is expressed in the cytoplasmic membrane of T-lymphocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells, and this expression may confer prognostic information.15 Furthermore, PD-L1 determination was different in each trial using different antibody clones and detection methods. Recent studies have determined that PD-L1 expression in NSCLC can be discordant due to different antibody affinities, limited specificity or distinct epitopes.16 These different methods could contribute to some of the heterogeneity found in our analysis. Still, efforts have been done to determine if a specific antibody confers a difference in the selection of any specific checkpoint inhibitor.17

Our findings confirm previous results showing that patients with high expression of PD-1/PD-L1 on immunohistochemistry derived the greatest benefit from immunotherapy in terms of OS. For example, the POPLAR study showed that the increased improvement in OS was associated with increased PD-L1 expression with use of atezolizumab in patients with previously treated NSCLC.18 This association between PD-L1 expression and response to therapy has been described in several clinical trials, including NSCLC and patients with melanoma,19 renal cell carcinoma,20 bladder carcinoma21 and gastric cancer.22 However, some other trials have not shown consistently shown between PD-L1 expression and the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors23 24

Although the PD-1/PD-L1 expression seems to be a useful biomarker, there are multiple challenges regarding its use as a predictive marker of immunotherapy efficacy. First, the expression of these proteins is a dynamic and heterogeneous process.25 Besides, previous studies have described some discrepancies in the expression of these proteins between the primary tumour and the metastatic site.26 Furthermore, other inflammatory cells can also express these proteins and may alter the pathologist’s interpretation.27 Other authors argue that different patterns of staining confer different prognosis.26 Despite these controversies, our data support current evidence that PD-L1 expression could be a useful biomarker to predict better responses to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

Our findings also showed that patients with EGFR wild-type NSCLC derived better OS improvement with anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 than tumours harbouring common EGFR mutations. Of note, the total proportion of patients with EGFR mutations was low (11.2%), and we cannot exclude the possibility of a type II error due to the small size of this particular subgroup in the whole sample. Besides, some of the included RCTs did not assess the EGFR status in the recruited patients. Despite these caveats, our findings are in line with previous studies showing that EGFR-mutated NSCLC has low mutation burden in comparison with wild-type EGFR tumours,28 and this low mutation burden can relate to a decreased sensitivity to checkpoint inhibitors. The mechanisms behind this association may be related to the overexpression of cytoplasmic neoantigens formed as consequence of somatic mutations that can be recognised by effector T-cells.29 30 Further analyses are warranted to determine the efficacy of immunotherapy in patients with common EGFR mutations as well as in patients harbouring ALK rearrangements.

The assessment of the secondary outcomes of this meta-analysis also favoured the immunotherapy arm in terms of PFS, overall response, duration of response and fewer side effects than chemotherapy with docetaxel. The overall HR for PFS was mainly derived from data from the CheckMate 017 Trial that showed a significant benefit in terms of progression for patients who received nivolumab in squamous NSCLC.10 Since treatment with checkpoint inhibitors was allowed beyond disease progression in all included trials, we considered that this finding is not clinically relevant.

However, we detected some heterogeneity between trials in the assessment of these secondary outcomes. Some sources of heterogeneity can be attributed to differences in the proportion of patients with PD-1/PD-L1 expression across the included trials. As previously described, the rate of response is highly dependent on PD-L1 positivity.23 24

Regarding side effects, trials assessing the efficacy of nivolumab in squamous and non-squamous NSCLC reported less grade 3 or higher toxicity (from 7% to 10%) in the experimental arm than trials using pembrolizumab or atezolizumab. Conversely, the included RCTs with nivolumab reported more toxicity from docetaxel use than the two remaining trials. Therefore, we suggest that the OR of treatment-related side effect is quite low among trials using nivolumab in comparison with RCTs using pembrolizumab and atezolizumab. However, the rate of discontinuation was very similar among the included trials, and the pattern of side effects was very similar among anti PD-1/PD-L1 therapies.

Our findings must be interpreted cautiously since all included studies have high risk of bias, especially performance and detection bias. These systematic errors could overestimate or underestimate the association measures of each trial. Besides, the aforementioned heterogeneity found in the secondary outcomes deserves further study to determine if there are efficacy differences among atezolizumab, nivolumab and pembrolizumab. However, our findings confirm the class effect of anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 therapy as a mainstay of treatment for patients with progressive advanced NSCLC.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings show an OS improvement of anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 therapy versus docetaxel in previously treated advanced NSCLC. PFS, overall response and duration of response also favoured the use of checkpoint inhibitors when compared with chemotherapy. In terms of side effects, even though the toxicity profile is different between checkpoint inhibitors and chemotherapy, grade 3 or higher adverse events were more likely seen with docetaxel.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data analysis. All authors contributed to the study concept and design. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding: This work was partially supported by Roche (no grant number is applicable).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2016;66:7–30. 10.3322/caac.21332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. International Agency for Research on Cancer. GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Default.aspx (accessed May 30, 2017).

- 3.Molina JR, Yang P, Cassivi SD, et al. . Non-small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorship. Mayo Clin Proc 2008;83:584–94. 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60735-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novello S, Barlesi F, Califano R, et al. . ESMO Guidelines Committee. Metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2016;27:v1–v27. 10.1093/annonc/mdw326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He X, Wang J, Li Y. Efficacy and safety of docetaxel for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of Phase III randomized controlled trials. Onco Targets Ther 2015;8:2023–31. 10.2147/OTT.S85648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khanna P, Blais N, Gaudreau PO, et al. . Immunotherapy Comes of Age in Lung Cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2017;18:13–22. 10.1016/j.cllc.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Mello RA, Veloso AF, Esrom Catarina P, et al. . Potential role of immunotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther 2017;10:21–30. 10.2147/OTT.S90459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, et al. . Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387:1540–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. . Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017;389:255–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. . Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:123–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. . Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1627–39. 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 1st ed: John Wiley & Sons, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. . New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228–47. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med 1998;17:2815–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, et al. . Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature 2014;515:563–7. 10.1038/nature14011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLaughlin J, Han G, Schalper KA, et al. . Quantitative Assessment of the Heterogeneity of PD-L1 Expression in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:46–54. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirsch FR, McElhinny A, Stanforth D, et al. . PD-L1 Immunohistochemistry Assays for Lung Cancer: Results from Phase 1 of the Blueprint PD-L1 IHC Assay Comparison Project. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:208–22. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.11.2228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M, et al. . Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387:1837–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00587-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kefford R, Ribas A, Hamid O, et al. . Clinical efficacy and correlation with tumor PD-L1 expression in patients (pts) with melanoma (MEL) treated with the anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody MK-3475. J Clin Oncol 2014;32. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motzer RJ, Rini BI, McDermott DF, et al. . Nivolumab for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: Results of a Randomized Phase II Trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1430–7. 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.0703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powles T, Eder JP, Fine GD, et al. . MPDL3280A (anti-PD-L1) treatment leads to clinical activity in metastatic bladder cancer. Nature 2014;515:558–62. 10.1038/nature13904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muro K, Bang Y-J, Shankaran V, et al. . Relationship between PD-L1 expression and clinical outcomes in patients (Pts) with advanced gastric cancer treated with the anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody pembrolizumab (Pembro; MK-3475) in KEYNOTE-012. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2015;33:3 10.1200/jco.2015.33.3_suppl.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellmunt J, de Wit R, Vaughn DJ, et al. . Pembrolizumab as Second-Line Therapy for Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1015–26. 10.1056/NEJMoa1613683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. . Nivolumab versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1803–13. 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meng X, Huang Z, Teng F, et al. . Predictive biomarkers in PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Cancer Treat Rev 2015;41:868–76. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meng X, Huang Z, Teng F, et al. . Predictive biomarkers in PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Cancer Treat Rev 2015;41:868–76. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, et al. . PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 2014;515:568–71. 10.1038/nature13954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spiegel DR, Schrock AB, Fabrizio D, et al. . Total mutation burden (TMB) in lung cancer (LC) and relationship with response to PD-1/PD-L1 targeted therapies. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:9017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. . Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 2015;348:124–8. 10.1126/science.aaa1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science 2011;331:1565–70. 10.1126/science.1203486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

esmoopen-2017-000236supp001.jpg (57.8KB, jpg)

esmoopen-2017-000236supp002.jpg (41.6KB, jpg)

esmoopen-2017-000236supp003.jpg (18.9KB, jpg)