Abstract

Background

The concepts of impulsivity and compulsivity are commonly used in psychiatry. Little is known about whether different manifest measures of impulsivity and compulsivity (behavior, personality, and cognition) map onto underlying latent traits; and if so, their inter-relationship.

Methods

A total of 576 adults were recruited using media advertisements. Psychopathological, personality, and cognitive measures of impulsivity and compulsivity were completed. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to identify the optimal model.

Results

The data were best explained by a two-factor model, corresponding to latent traits of impulsivity and compulsivity, respectively, which were positively correlated with each other. This model was statistically superior to the alternative models of their being one underlying factor (‘disinhibition’) or two anticorrelated factors. Higher scores on the impulsive and compulsive latent factors were each significantly associated with worse quality of life (both p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

This study supports the existence of latent functionally impairing dimensional forms of impulsivity and compulsivity, which are positively correlated. Future work should examine the neurobiological and neurochemical underpinnings of these latent traits; and explore whether they can be used as candidate treatment targets. The findings have implications for diagnostic classification systems, suggesting that combining categorical and dimensional approaches may be valuable and clinically relevant.

Key words: Addiction, cognition, compulsive, habit, impulsive

Introduction

There is a growing realization that the careful elucidation and measurement of intermediate biological characteristics is central to refining and improving existing psychiatric classification and treatment. As highlighted in the NIMH Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) strategic plan, it is necessary to identify intermediate markers, cutting across related psychiatric disorders, and continuous with relevant markers of variability in the general population (Cuthbert & Insel, 2013). The concepts of impulsivity and compulsivity are highly relevant clinically, but also represent fruitful heuristics in the search for intermediate markers of psychiatric disease. Impulsivity refers to behaviors or actions that are inappropriate, premature, unduly thought out, risky, and that lead to untoward outcomes (Evenden, 1999). Compulsivity refers to a tendency toward repetitive, habitual actions, repeated despite adverse consequences (Robbins et al. 2012). It has been suggested that impulsivity and compulsivity might constitute opposite ends of a spectrum (Stein et al. 1993). However, impulsive and compulsive symptoms can co-occur within the same individual, hence the suggestion that they may be driven by common neurobiological processes (such as lack of top–down executive control, or ‘disinhibition’) (Chamberlain et al. 2005). Impulsivity–compulsivity constitutes one of several candidate dimensional models in psychiatry. Other key examples include internalizing (depression, generalized anxiety) v. externalizing (e.g. substance use, antisocial personality) symptoms (Khan et al. 2005); and depression v. mania (the ‘mood spectrum’) (McElroy et al. 1996). These different frames of references can be viewed as being partly related.

At the level of symptoms, impulsive behaviors are explicitly listed in the diagnostic criteria for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and several other conditions formally listed as ‘Impulse Control Disorders’ in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Version 5 (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Symptoms reaching formal diagnostic criteria for ADHD are evident in up to 7% of children and 2.5% of adults (Simon et al. 2009). Compulsivity is well represented in obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD; intrusive thoughts and/or repetitive rituals) and in obsessive–compulsive personality disorder (OCPD; e.g. rigid, perfectionistic approach to life with reluctance to delegate) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Formal OCD affects 1–3% of the population, and OCPD up to 8% (Grant et al. 2014; Diedrich & Voderholzer, 2015). Obsessive–compulsive traits exist in milder forms and can be quantified using questionnaires designed for this purpose (Sanavio, 1988). Compulsivity is also a core behavioral feature in gambling disorder or substance use disorders – conditions now listed together in the DSM-5 category of ‘Substance Related and Addictive Disorders’. These disorders are also common (prevalence of 8.5% for alcohol use disorder and up to 3.1% for gambling disorder) (Grant et al. 2004a; Ferguson et al. 2011).

Impulsivity and compulsivity can be conceptualized not only in terms of overt psychopathology, such as described above, but also in terms of personality- and laboratory-based neurocognitive measures. There is an extensive literature on the development and validation of questionnaire-based measures of personality related to impulsivity (e.g. the Barratt Impulsiveness Questionnaire), and compulsivity (e.g. the Padua Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory) (Barratt, 1965; Sanavio, 1988). These measures are well suited for use at the level of the general population, but are also sensitive to more extreme levels of impulsivity and compulsivity as manifested in ADHD and OCD, respectively (Malloy-Diniz et al. 2007; van den Heuvel et al. 2008). From a cognitive perspective, facets of impulsivity can be captured using tests of premature motor response (stop-signal tasks), and gambling paradigms examining tendency for making risky decisions (Grant & Chamberlain, 2014). Similarly, aspects of compulsivity can be fractionated using tests of flexible responding, especially set-shifting (Robbins et al. 2012), and measures of rigidity on other tests. Inroads have been made in eliciting the neural and neurochemical substrates underlying normal performance on these tasks across species (Robbins, 2005; Dalley et al. 2011; Bari & Robbins, 2013; Fineberg et al. 2014). Dysfunction of these fronto-striatal systems is central to neurobiological models and treatment of impulsive and compulsive conditions (Denys et al. 2004; Biederman & Faraone, 2005; Del Campo et al. 2011; Seixas et al. 2012).

The concepts of impulsivity and compulsivity have contributed to the latest nosological classification systems in psychiatry, and are critical concepts when considering treatments for mental disorders. Yet, it is not yet known whether latent phenotypes of impulsivity and compulsivity exist; if so, whether they are related; and if so, how. Therefore, we quantified whether impulsive and compulsive data were optimally explained by there being one underlying latent factor, two underlying unrelated latent factors, or two underlying related latent factors. It was hypothesized that impulsive and compulsive variables would load onto two largely separable, but positively correlated latent traits.

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants, aged 18–29 years, were recruited using media advertisements in two US cities. Adverts asked subjects to participate in a research study exploring impulsive/compulsive behaviors. Subjects were excluded if they were unable to give informed consent, were unable understand/undertake the study procedures, or were seeking treatment for any mental disorders. All study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Boards of the Universities of Minnesota and Chicago approved the study and the consent statement. Participants were compensated with a $50 gift card for a local department store for taking part.

Clinical assessments

Assessments were conducted in a quiet testing room with a trained rater, and included objective clinical interview, completion of questionnaires, and neuropsychological assessment using a touch-screen computer. An overview of the measures is provided in Table 1 below. We focused on measures of impulsivity and compulsivity, categorized as such a priori on the basis of current psychiatric models and nosology.

Table 1.

Overview of outcome measures collected as part of the study

| Measurement category | Instrument used | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Age | – | – | – |

| Gender | – | – | – |

| Education | – | – | – |

| Quality of life | Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI) | Quality of life t-score, based on responses to 32 items, encompassing well-being and life satisfaction | Frisch et al. (1992) |

| Impulsivity | |||

| Psychopathology | |||

| Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms | World ADHD Rating Scale (ASRS v1.1), Part A | Gives total score, which indicates risk of underlying ADHD diagnosis | Kessler et al. (2005) |

| Suicidality | Mini International Neuropsychiatric Inventory (MINI) | Generates total score related to history of self-endangerment, suicidal thoughts, and suicide attempt(s). Score held to reflect current suicide risk | Sheehan et al. (1998) |

| Personality | |||

| Antisocial personality disorder | MINI | Binary measure as to whether criteria met for antisocial personality disorder, based on structured clinical interview | Sheehan et al. (1998) |

| Motor, non-planning, and attentional impulsivity | Barratt Impulsiveness Questionnaire (BIS-11) | Yields three total sub-scores based on previous factor analysis | Barratt (1965), Patton et al. (1995) |

| Impulsiveness, venturesomeness, and extraversion | Eysenck Personality Inventory | Yields three total sub-scores based on previous factor analysis | Eysenck & Eysenck (1978), Eysenck & Eysenck (1977) |

| Cognition | |||

| Response inhibition | CANTAB Stop-Signal Task (SST) | Estimates time taken for individual's brain to suppress a pre-potent response (stop-signal reaction time) | Aron et al. (2007), Logan et al. (1984) |

| Quality of decision-making | CANTAB Cambridge Gamble Task (CGT) | Measures tendency of individual to make impulsive decisions contrary to logic | Rogers et al. (1999) |

| Compulsivity | |||

| Psychopathology | |||

| Gambling disorder | Minnesota Impulse Disorders Inventory (MIDI) module | Binary presence/absence of gambling disorder, based on structured clinical interview | Grant et al. (2004b) |

| Gambling frequency | Structured interview | Person asked how many times they gamble in a typical week | – |

| Gambling severity | Pathological-Gambling Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (PG-YBOCS) | Total score, based on thoughts and behaviors related to problem/pathological gambling | Pallanti et al. (2005) |

| Alcohol use disorder (AUD) | MINI | Binary measure as to presence or absence of AUD (dependence/abuse), based on structured clinical interview | Sheehan et al. (1998) |

| Alcohol frequency | Structured interview | Person asked how many times they consume one or more alcoholic beverages per week | – |

| Substance use disorder (SUD) | MINI | Binary measure as to presence or absence of SUD (dependence/abuse, any substance besides alcohol), based on structured clinical interview | Sheehan et al. (1998) |

| Marihuana consumption | In-person interview | Person asked how many times they consume cannabis per week | |

| Nicotine consumption | In-person interview | Person asked how much they smoke; responses converted to ‘packs per day’ equivalent | |

| Problematic use of the Internet | Young's Diagnostic Questionnaire | Gives total score as to how many criteria met for problematic Internet use (max 8) | Young (2009) |

| Eating disorder | MINI | Binary as to presence/absence of any eating disorder, based on structured clinical interview | Sheehan et al. (1998) |

| Personality | |||

| Obsessive–compulsive (OC) symptoms | Padua Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory Revised | Thirty-nine-item questionnaire, which yields five scores for different OC factors | Burns et al. (1996), Sanavio, (1988) |

| Obsessive–compulsive personality disorder score | DSM-IV symptom tick-list | Total score as to how many of eight symptom criteria met | American Psychiatric Association (2000) |

| Cognition | |||

| Extra-dimensional set-shifting | CANTAB Intra-Dimensional/Extra-Dimensional Set-Shift Task (IED) | Errors made during the crucial extra-dimensional shift stage of the test | Pantelis et al. (1999) |

| Reversal learning | CANTAB IED | Total number of errors made for all reversal learning stages of the test | Pantelis et al. (1999) |

| Risk adjustment | CANTAB CGT | Measures the extent to which participants modulate their behavior depending on risk level (flexible decision-making) | Rogers et al. (1999) |

Psychopathological measures of impulsivity comprised ADHD symptom scores, occurrence of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), and suicidal tendencies. Impulsive symptoms are listed explicitly in the diagnostic criteria for ADHD and ASPD, whereas many studies have reported strong – even heritable – associations between impulsivity and suicide-related behaviors (Chistiakov et al. 2012). For personality-related measures of impulsivity, we included the Barratt Impulsivity and Eysenck personality questionnaires, which are widely used and accepted for such purposes (Gomez & Corr, 2014; Stanford et al. 2016). For cognitive measures of impulsivity, we focused on the inhibition of pre-potent motor responses on the Stop-Signal Test (SST), and the tendency to make irrational decisions to the detriment of longer term performance on the Cambridge Gamble Test (CGT). Decisional and motor impulsivity are widely recognized as distinct cognitive manifestations of impulsivity (Dalley et al. 2011; MacKillop et al. 2016). See online Supplementary file for more detailed description of the cognitive tasks.

Compulsive measures of psychopathology included those reflecting gambling, substance use, compulsive use of the Internet, and eating disorders. Compulsivity is central to understanding the neurobiology of gambling and substance use disorders, in that they are characterized by maladaptive repetitive engagement in habitual behaviors that are reinforcing (implicating dysfunctional reward circuitry) (Grant & Chamberlain, 2016). Symptoms of dependence and withdrawal are extremely common in substance and gambling disorders, serving to perpetuate narrowing of the behavioral repertoire (Wareham & Potenza, 2010). While not yet regarded as a formal psychiatric disorder, problematic Internet use is relatively commonplace. Its working diagnostic criteria incorporate compulsive use (based on parallels with substance use disorders) (Young, 2009). Based on an extensive review of available literature, compulsive use has been highlighted as a core symptom of Internet addiction (Kuss et al. 2014). Compulsivity has emerged as a key construct in understanding eating disorders – pathological overeating (Degortes et al. 2014; Moore et al. 2017), as well as in anorexia nervosa (Tenconi et al. 2010; Degortes et al. 2014; Treasure et al. 2015). For compulsive personality, obsessive–compulsive symptom traits on the Padua Inventory revised (Burns et al. 1996; Sanavio, 1988), and OCPD traits (based on number of DSM criteria met), were quantified. We used Padua Inventory rather than the OCD Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Scale (YBOCS) because the Padua Inventory is designed to explore obsessive–compulsive traits and symptoms at the population level; using the YBOCS in a normative population would likely have yielded very limited variation in scores, with most participants scoring zero. For compulsive cognition, we measured reversal learning and extra-dimensional set-shifting on the Intra-Dimensional/Extra-Dimensional Set-Shift Task (IED); along with risk adjustment on the Cambridge Gamble Task (CGT). Reversal learning and extra-dimensional set-shifting are two key, separable components of behavioral flexibility germane to understanding compulsivity (Clarke et al. 2005; Clarke et al. 2007; Chamberlain & Menzies, 2009; Dalley et al. 2011). It was hypothesized that difficulty adjusting behavior as a function of risk on the CGT would constitute a measure of decision-making sensitive to rigid response styles. See online Supplementary file for more detailed description of the cognitive tasks.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were undertaken using R software, MPlus, and IBM SPSS (v22.0) (Muthén & Muthén, 2016; R Core Team, 2016).

Impulsive and compulsive measures of interest were analyzed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to compare three models: one in which impulsive and compulsive measures were underpinned by a single underlying latent factor; one in which covariances among impulsive and compulsive measures were explained by two underlying unrelated latent factors; and one in which covariances were explained by two underlying related latent factors. Our aim was to test the relationship between these latent factors, rather than to explore the possible existence of other additional latent factors. As such, and in view of the extensive literature supporting the existence of these two latent types of measurement (impulsivity and compulsivity) (Robbins et al. 2012; Guo et al. 2017), CFA rather than exploratory factor analysis was appropriate. We included behavioral, personality, and cognitive measures on the same conceptual plane to maintain simplicity of the examined models but also because the distinction between these categories of measure is far from clear. DSM-5 places personality disorders and disorders formally regarded as being on ‘axis-I’ on the same conceptual plane, in recognition of overlap between them. Many measures can be argued to be in one category or another depending on vantage point. To assure comparability, the model fit was evaluated using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) (Akaike, 1974; Schwarz, 1978).

Results

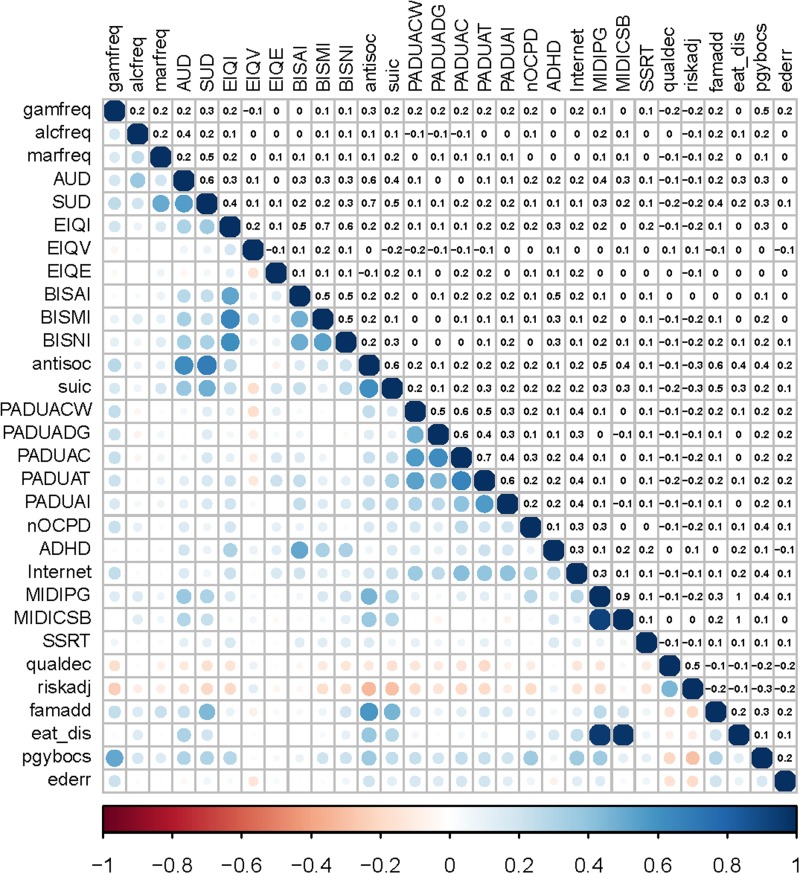

The sample comprised 576 individuals [mean age (s.d.) = 22.3 (3.6) years; 65.5% male]. The average quality of life, Barratt impulsiveness scores, Padua obsessive–compulsive scores, and cognitive scores were similar to those reported in previous normative datasets (for further discussion and distribution of individual measures see online Supplementary file). Correlations between individual measures of interest are summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Heat map showing correlations between variables of interest. Left: positive correlations are shown in blue, and negative in red; larger dots are indicative of stronger correlations. Right: correlation coefficients (rounded to one decimal place in the interests of clarity). gamfreq, gambling frequency per week; alcfreq, alcohol frequency per week; marfreq, marihuana frequency per week; AUD, alcohol use disorder; SUD, substance use disorder; EIQI, Eysenck Inventory Impulsiveness; EIQV, Eysenck Inventory Venturesomeness; EIQE, Eysenck Inventory Extraversion; BISAI, Barratt Attentional Impulsiveness; BISMI, Barratt Motor Impulsiveness; BISNI, Barratt Non-Planning Impulsiveness; antisoc, antisocial personality disorder; suic, suicidality on the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Inventory; PADUACW, Padua Inventory Contamination and Washing subscale; PADUADG, Padua Inventory Dressing/Grooming subscale; PADUAC, Padua Inventory Checking subscale; PADUAT, Padua Inventory Thoughts of Harm to Self-others subscale; PADUAI, Padua Inventory Impulses to Harm Self/Others subscale; nOCPD, number of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder criteria met; ADHD, total score on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder screen; Internet, total score on Young's Internet Addiction Test; MIDIPG, gambling disorder; SSRT, stop-signal reaction time on Stop-Signal Test; qualdec, quality of decision-making on the Cambridge Gamble Test; riskadj, risk adjustment on the Cambrige Gamble Test; eat_dis, eating disorder; pgybocs, Pathological Gambling Yale Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder Scale; ederr, extra-dimensional errors on the set-shifting task.

Confirmatory factor analysis

Fit indices for the different confirmatory factor models are summarized in Table 2; it can be seen that the model with two correlated latent factors had the best fit (lowest information criteria scores). This model was re-estimated using weighted least squares to assess its absolute fit, which yielded parameters as follows: global fit index 0.977, root mean square error of approximation 0.064, and comparative fit index 0.86. These values are considered to indicate reasonably good fit, in view of conventional criteria, taking into consideration the sample size (Hu & Bentler, 2009). Comparing the hypothesized models using weight of evidence, the two-factor correlated model was the best fit (>99.9% probability).

Table 2.

Maximum likelihood-based fit indices

| Model | AIC | BIC | aBIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-factor | 53 978 | 54 301 | 54 066 |

| Two-factor uncorrelated | 53 212 | 53 535 | 53 300 |

| Two-factor correlated | 53 186 | 53 513 | 53 275 |

Lower scores indicate better model fit, and a reduction of 10 or more units from one model to another is generally held to indicate a superior model (Raftery, 1995).

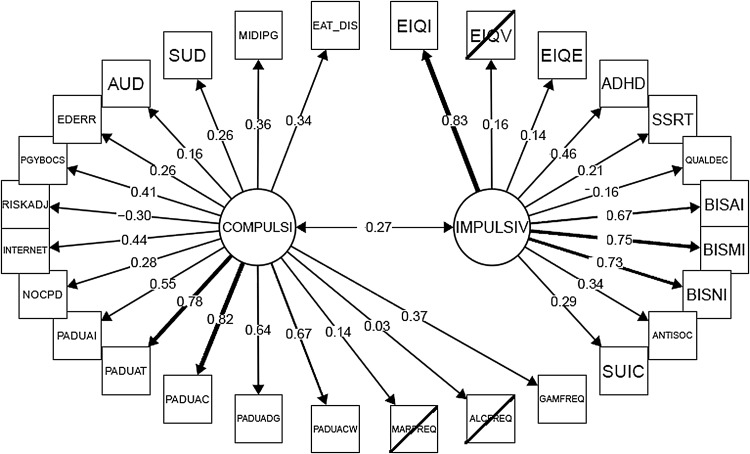

The loadings of manifest measures onto the optimal two-factor model are shown in Fig. 2. Variable loadings were in the expected direction, such that higher impulsivity factor scores were associated with higher personality measures of impulsivity, higher impulsive symptomatology (ASPD, ADHD, suicidality), and worse quality of decision-making on the gambling task; and higher compulsivity factor scores were associated with higher personality measures of compulsivity (Padua Inventory), higher compulsive symptomatology (gambling, problematic Internet use, OCPD, substance use disorders), more extra-dimensional set-shifting errors on the set-shifting task, and less risk adjustment on the gambling task.

Fig. 2.

Two-factor correlated model, showing factor loadings. Variables with non-statistically significant loading (p > 0.05) are shown in strike-through. Abbreviations – see footer to Fig. 1.

Higher scores on the impulsivity and compulsivity factors, respectively, were significantly correlated with worse quality of life on the Quality of Life Inventory (r = 0.27, p < 0.00001; and r = 0.30, p < 0.000001).

Discussion

Mental disorders characterized by impulsive or compulsive symptoms constitute a huge burden for patients, family members, and society at large. Psychiatry is seeking methods of refining the definition of mental disorders, and of better understanding their etiology and neurobiological substrates. One way of tackling this challenge (Cuthbert & Insel, 2013), is to use a multi-tiered approach examining not just categorical mental disorders but also dimensional psychopathology, personality, and neurocognitive functioning (Chamberlain & Menzies, 2009). Here, we examined such multi-tiered measures in a sample of young adults who were not treatment seeking. We found that impulsive and compulsive manifest measures were underpinned by distinct latent traits of impulsivity and compulsivity, which were positively correlated with each other. Furthermore, higher scores on each of these latent traits were significantly correlated with worse quality of life, thereby confirming their clinical relevance. The two correlated factor model was a better fit to the data than alternative conceptual models in which impulsive and compulsive manifest measures were mediated by a single latent factor of ‘disinhibition’; and the alternative conceptualizations that impulsive and compulsive latent traits were in opposition to each other (negatively correlated) or independent of each other. We focused on impulsivity and compulsivity, which we view as being complementary to other suggested frameworks for understanding mental disorders, such as the idea of externalizing v. internalizing symptoms; or the existence of a bipolar mood spectrum. Impulsivity and compulsivity are related to these other models but are not the same thing (Eisenberg et al. 2009). Ultimately, psychiatry may benefit from a more cohesive model that integrates multiple of these ideas (Lara & Akiskal, 2006).

Manifest measures loading most strongly and significantly on the latent trait of impulsivity (see Fig. 2) were (in descending order of statistical significance): impulsiveness on the Eysenck Inventory, impulsiveness on the Barratt questionnaire, dimensional ADHD symptoms, presence of ASPD, suicide risk, longer stop-signal reaction times, and extraversion on the Eysenck Inventory. As a caveat, it should be noted that some of these loadings, while statistically significant, were relatively small in magnitude. These findings are consistent with studies in clinical populations, which have reported positive associations between such personality-based measures of impulsivity, and ADHD (Malloy-Diniz et al. 2007); and between such personality-based measures and ASPD (Swann et al. 2009). There is also evidence that Barratt impulsiveness was associated with suicidality in the context of depressive symptoms (Swann et al. 2008). Stop-signal reaction time impairment has been observed in meta-analysis of available cognitive studies comparing ADHD groups to healthy volunteers (Lijffijt et al. 2005; Chamberlain et al. 2011). In non-treatment-seeking adults with ASPD, stop-signal deficits were observed v. healthy controls (Heritage & Benning, 2013; Chamberlain et al. 2016).

In contrast to research regarding impulsivity, the exploration of compulsivity has received relatively little research attention (Robbins et al. 2012). Manifest measures of compulsivity that loaded significantly onto the latent factor of compulsivity were as follows (in descending order of statistical significance): obsessive–compulsive symptoms on the Padua Inventory, problematic Internet use, problem gambling symptoms, presence of an eating disorder, less risk adjustment on the CGT, OCPD traits, more extra-dimensional set-shift errors on the Set-Shift Task (IED), and presence of substance/alcohol use disorder. Again, some of these variables had relatively low loading onto the latent construct, albeit they were significant. Compulsivity has been defined, hypothetically, as an intermediate phenotype or trait characterized by persistence of habitual/repetitive actions despite untoward consequences (Robbins et al. 2012). Our data are supportive of the view that compulsivity can be conceptualized as such a trait, and demonstrate that it is largely separable from impulsivity. Relatively impaired set-shifting has been identified in patients with OCD (Veale et al. 1996; Watkins et al. 2005; Chamberlain et al. 2007), and in those with eating disorders (Kanakam & Treasure, 2013; Aloi et al. 2015; Perpina et al. 2016), compared with healthy controls. Set-shifting errors, and reduction of behavioral adjustment as a function of risk, are both indicative of inflexible or habitual response styles. One interpretative model is that these response patterns may be due to a tendency toward habitual behaviors at the expense of goal-directed behaviors (Gillan & Robbins, 2014). In a large-scale Internet-based study, deficits in goal-directed control were strongly associated with compulsive behaviors and intrusive thoughts, but were also associated to a lesser degree with impulsivity on the Barratt questionnaire (Gillan et al. 2017).

Problematic Internet use is not yet considered a mental disorder in DSM-5, but has been highlighted as a concept in need of further study (in this and other narrower guises, such as ‘Internet Gaming Disorder’) (Grant & Chamberlain, 2016). Studies report high rates of mental disorders including OCD in people with pathological Internet use (Carli et al. 2013; Durkee et al. 2016). In an Internet-based survey, some types of obsessive–compulsive symptoms (impulses to harm self/others and checking compulsions) were the most important variables across impulsive–compulsive measures in terms of classifying participants as having moderate–severe Internet addiction (Ioannidis et al. 2016). Research into OCPD is scant, but data indicate disproportionately worse set-shifting impairment in OCD patients with this comorbidity (Fineberg et al. 2007; Fineberg et al. 2015). Our finding that substance use disorders loaded significantly and positively onto the latent compulsivity factor is unsurprising. Criteria for substance use disorders includes features such as narrowing of the behavioral repertoire, persistently engaging in use despite negative consequences, and unsuccessful attempts to cut back, which fit the concept of compulsivity closely.

To our knowledge, no previous studies have explored the latent structure of impulsivity and compulsivity measures within one setting, using such a broad range of measures. However, there is an extensive body of literature, mostly focusing on psychopathology, suggesting the existence of an underlying ‘internalizing’ dimension (predisposition to anxiety/depressive disorders) and an ‘externalizing’ dimension (predisposition to, e.g. substance use, antisocial personality, ADHD) (Caspi et al. 2014). OCD symptoms have not been consistently included in studies exploring the structure of psychopathology (Caspi et al. 2014). In a large sample of adolescents (IMAGEN consortium), the best-fit model for selected psychopathological measures comprised two factors (compulsivity and externalizing behaviors) (Montigny et al. 2013). The compulsivity factor showed strong associations with OCD and eating disorders, whereas the externalizing behaviors factor showed strong associations with substance misuse, conduct disorder, and (to a lesser degree) ADHD symptoms. In another paper by the same research consortium (IMAGEN), psychopathological measures were first entered into initial CFA (Castellanos-Ryan et al. 2016). The relationships between resulting factors and other measures, such as cognitive functioning were then explored. The authors opted for a bi-factor model incorporating three factors. It was found that a general psychopathology factor correlated with worse response inhibition and greater temporal discounting; an externalizing factor correlated with high risk taking on a gambling task; and that an internalizing factor correlated with attentional bias toward negatively valenced verbal stimuli. This study measured impulsivity with a go/no-go task (rather than a stop-signal task), and did not quantify attentional set-shifting.

The current study has several limitations, which merit consideration. Our sample did not exclude people with mental disorders. This can be viewed as being beneficial to exploring latent traits of impulsivity and compulsivity since it would have yielded a broader set of data for the purposes of measuring covariance, and is also parsimonious with the RDoc concept. Our sample showed average impulsive and compulsive personality questionnaire scores, and cognitive performance, akin to that reported in previous normative populations. However, the findings may not generalize to other populations, such as patients in clinical settings. We treated personality, symptoms, and cognition as being on the same conceptual plane, with a view to maintaining model simplicity and avoiding unnecessary assumptions. We used confirmatory rather than exploratory factor analysis because the concepts of impulsivity and compulsivity are well established in the literature (Hollander & Cohen, 1996; Robbins et al. 2012) and our research question pertained to the relationship between them, rather than the separate issue of whether more latent factors exist. For pragmatic reasons, we did not include all possible measures of relevance to impulsivity and compulsivity. For example, we did not assess reflection–impulsivity, or tasks of ‘incremental’ habit learning (Gillan & Robbins, 2014; Hauser et al. 2016). It would be valuable to include such parameters in future work. Lastly, some recent studies of personality and psychopathology have explored bi-factor models. In bi-factor models, a general factor or ‘p’ (analogous to the historical ‘g’ factor in intelligence quotient research) is included, on the assumption that a proportion of covariance across all measures may measure a common trait (Caspi et al. 2014). The findings from the two correlated factor model suggest against using a bi-factor structure for the current data, because the proportion of shared variance between the impulsivity and compulsivity factors was only ~7%. Furthermore, bi-factor models may be intrinsically biased toward yielding superior model fit parameters over non bi-factor models, as a consequence of unmodeled complexity (Murray & Johnson, 2013). In post hoc analysis, furthermore, we found that the ω coefficient was inferior when a bi-factor model fit was applied to the data (ω < 0.7 for the general factor), v. the two correlated factor model (ωimpulsivity = 0.74; ωcompulsivity = 0.79) (Reise, 2012). The biological and clinical plausibility and interpretation of ‘g’ or ‘p’ factor may be problematic (Vanheule et al. 2008) – for example, ‘p’ could represent response style rather than containing substantial meaning.

In summary, this study used a range of psychopathological, personality, and cognitive measures to demonstrate the existence of two separable but positively correlated latent traits of impulsivity and compulsivity, in a sample of young adults recruited from the background population. Higher scores on each latent trait was significantly correlated with worse quality of life, and was associated with greater risk of having one or more relatives with a behavioral or substance addiction, supporting the clinical relevance of these traits.

We do not suggest that all manifest measures of impulsivity and compulsivity are ‘two things’; there is evidence, for example, that different measures of impulsivity can be fractionated (Meda et al. 2009; MacKillop et al. 2016). However, the current findings do support the notion that latent forms of impulsivity and compulsivity exist in a dimensional or continuous sense that they are largely separable from each other, and that higher impulsivity tends to associate with higher compulsivity (rather than the opposite). Treatments targeting impulsivity and compulsivity at the conceptual level, or in terms of specific manifest forms (such as neurocognitive impairment), would be potentially valuable. Future work should identify neural and neurochemical underpinnings of these latent dimensions with a view to informing nosological and neurobiological models; and should also attempt to integrate multiple candidate dimensions besides impulsivity and compulsivity.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a Wellcome Trust Clinical Fellowship to Dr Chamberlain (UK; Reference 110049/Z/15/Z) and by a Center of Excellence in Gambling Research grant from the National Center for Responsible Gaming to Dr Grant (USA). Dr Stochl was partly supported by Charles University PRVOUK program number P38. The authors would like to thank all study participants.

Declaration of Interest

Dr Chamberlain consults for Cambridge Cognition. Dr Grant has received research grants from NIMH, National Center for Responsible Gaming, and Forest and Roche Pharmaceuticals. He receives yearly compensation from the Springer Publishing for acting as Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Gambling Studies and has received royalties from the Oxford University Press, American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., Norton Press, and McGraw Hill.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002185.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- Akaike H (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar]

- Aloi M, Rania M, Caroleo M, Bruni A, Palmieri A, Cauteruccio MA, De Fazio P, Segura-Garcia C (2015). Decision making, central coherence and set-shifting: a comparison between binge eating disorder, anorexia nervosa and healthy controls. BMC Psychiatry 15, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.) (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Aron AR, Durston S, Eagle DM, Logan GD, Stinear CM, Stuphorn V (2007). Converging evidence for a fronto-basal-ganglia network for inhibitory control of action and cognition. Journal of Neuroscience 27, 11860–11864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari A, Robbins TW (2013). Inhibition and impulsivity: behavioral and neural basis of response control. Progress in Neurobiology 108, 44–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt ES (1965). Factor analysis of some psychometric measures of impulsiveness and anxiety. Psychological Reports 16, 547–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV (2005). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet 366, 237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns GL, Keortge SG, Formea GM, Sternberger LG (1996). Revision of the Padua Inventory of obsessive compulsive disorder symptoms: distinctions between worry, obsessions, and compulsions. Behaviour Research and Therapy 34, 163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carli V, Durkee T, Wasserman D, Hadlaczky G, Despalins R, Kramarz E, Wasserman C, Sarchiapone M, Hoven CW, Brunner R, Kaess M (2013). The association between pathological internet use and comorbid psychopathology: a systematic review. Psychopathology 46, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Goldman-Mellor SJ, Harrington H, Israel S, Meier MH, Ramrakha S, Shalev I, Poulton R, Moffitt TE (2014). The p factor: one general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clinical Psychological Science 2, 119–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos-Ryan N, Briere FN, O'Leary-Barrett M, Banaschewski T, Bokde A, Bromberg U, Buchel C, Flor H, Frouin V, Gallinat J, Garavan H, Martinot JL, Nees F, Paus T, Pausova Z, Rietschel M, Smolka MN, Robbins TW, Whelan R, Schumann G, Conrod P, IMAGEN Consortium (2016). The structure of psychopathology in adolescence and its common personality and cognitive correlates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 125, 1039–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Blackwell AD, Fineberg NA, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ (2005). The neuropsychology of obsessive compulsive disorder: the importance of failures in cognitive and behavioural inhibition as candidate endophenotypic markers. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 29, 399–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Derbyshire KL, Leppink EW, Grant JE (2016). Neurocognitive deficits associated with antisocial personality disorder in non-treatment-seeking young adults. Journal of American Academic Psychiatry Law 44, 218–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Fineberg NA, Menzies LA, Blackwell AD, Bullmore ET, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ (2007). Impaired cognitive flexibility and motor inhibition in unaffected first-degree relatives of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 164, 335–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Menzies L (2009). Endophenotypes of obsessive-compulsive disorder: rationale, evidence and future potential. Expert Reviews in Neurotherapeutics 9, 1133–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Robbins TW, Winder-Rhodes S, Muller U, Sahakian BJ, Blackwell AD, Barnett JH (2011). Translational approaches to frontostriatal dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder using a computerized neuropsychological battery. Biological Psychiatry 69, 1192–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chistiakov DA, Kekelidze ZI, Chekhonin VP (2012). Endophenotypes as a measure of suicidality. Journal of Applied Genetics 53, 389–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke HF, Walker SC, Crofts HS, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Roberts AC (2005). Prefrontal serotonin depletion affects reversal learning but not attentional set shifting. Journal of Neuroscience 25, 532–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke HF, Walker SC, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Roberts AC (2007). Cognitive inflexibility after prefrontal serotonin depletion is behaviorally and neurochemically specific. Cerebral Cortex 17, 18–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN, Insel TR (2013). Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Medicine 11, 126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW (2011). Impulsivity, compulsivity, and top-down cognitive control. Neuron 69, 680–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degortes D, Zanetti T, Tenconi E, Santonastaso P, Favaro A (2014). Childhood obsessive-compulsive traits in anorexia nervosa patients, their unaffected sisters and healthy controls: a retrospective study. European Eating Disorders Review 22, 237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Campo N, Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW (2011). The roles of dopamine and noradrenaline in the pathophysiology and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry 69, e145–e157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denys D, Zohar J, Westenberg HG (2004). The role of dopamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder: preclinical and clinical evidence. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65(Suppl 14), 11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diedrich A, Voderholzer U (2015). Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder: a current review. Current Psychiatry Reports 17, 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkee T, Carli V, Floderus B, Wasserman C, Sarchiapone M, Apter A, Balazs JA, Bobes J, Brunner R, Corcoran P, Cosman D, Haring C, Hoven CW, Kaess M, Kahn JP, Nemes B, Postuvan V, Saiz PA, Varnik P, Wasserman D (2016). Pathological internet use and risk-behaviors among European adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 13, 294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Liew J, Zhou Q, Losoya SH, Reiser M, Cumberland A (2009). Longitudinal relations of children's effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Developmental Psychology 45, 988–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL (1999). Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 146, 348–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG (1978). Manual for the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. Hodder & Stoughton: London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SB, Eysenck HJ (1977). The place of impulsiveness in a dimensional system of personality description. The British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 16, 57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ, Coulson M, Barnett J (2011). A meta-analysis of pathological gaming prevalence and comorbidity with mental health, academic and social problems. Journal of Psychiatric Research 45, 1573–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg NA, Chamberlain SR, Goudriaan AE, Stein DJ, Vanderschuren LJ, Gillan CM, Shekar S, Gorwood PA, Voon V, Morein-Zamir S, Denys D, Sahakian BJ, Moeller FG, Robbins TW, Potenza MN (2014). New developments in human neurocognition: clinical, genetic, and brain imaging correlates of impulsivity and compulsivity. CNS Spectrums 19, 69–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg NA, Day GA, de Koenigswarter N, Reghunandanan S, Kolli S, Jefferies-Sewell K, Hranov G, Laws KR (2015). The neuropsychology of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder: a new analysis. CNS Spectrums 20, 490–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg NA, Sharma P, Sivakumaran T, Sahakian B, Chamberlain SR (2007). Does obsessive-compulsive personality disorder belong within the obsessive-compulsive spectrum? CNS Spectrums 12, 467–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch MB, Cornell J, Villanueva M, Retzlaff PJ (1992). Clinical validation of the Quality of Life Inventory: a measure of life satisfaction for use in treatment planning and outcome assessment. Psychological Assessment 4, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Gillan CM, Fineberg NA, Robbins TW (2017). A trans-diagnostic perspective on obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychological Medicine 47, 1528–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillan CM, Robbins TW (2014). Goal-directed learning and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Science 369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez R, Corr PJ (2014). ADHD and personality: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review 34, 376–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP (2004a). The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 74, 223–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Chamberlain SR (2014). Impulsive action and impulsive choice across substance and behavioral addictions: cause or consequence? Addictive Behaviors 39, 1632–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Chamberlain SR (2016). Expanding the definition of addiction: DSM-5 vs. ICD-11. CNS Spectrums 21, 300–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Chamberlain SR, Odlaug BL (2014). Clinical Guide to Obsessive Compulsive and Related Disorders. Oxford University Press: New York, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Steinberg MA, Kim SW, Rounsaville BJ, Potenza MN (2004b). Preliminary validity and reliability testing of a structured clinical interview for pathological gambling. Psychiatry Research 128, 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo K, Youssef GJ, Dawson A, Parkes L, Oostermeijer S, Lopez-Sola C, Lorenzetti V, Greenwood C, Fontenelle LF, Yucel M (2017). A psychometric validation study of the Impulsive-Compulsive Behaviours Checklist: a transdiagnostic tool for addictive and compulsive behaviours. Addictive Behaviors 67, 26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser TU, Eldar E, Dolan RJ (2016). Neural mechanisms of harm-avoidance learning: a model for obsessive-compulsive disorder? JAMA Psychiatry 73, 1196–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heritage AJ, Benning SD (2013). Impulsivity and response modulation deficits in psychopathy: evidence from the ERN and N1. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 122, 215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander E, Cohen LJ (1996). Impulsivity and Compulsivity. American Psychiatric Press Inc, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM (2009). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis K, Chamberlain SR, Treder MS, Kiraly F, Leppink EW, Redden SA, Stein DJ, Lochner C, Grant JE (2016). Problematic internet use (PIU): associations with the impulsive-compulsive spectrum. An application of machine learning in psychiatry. Journal of Psychiatric Research 83, 94–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanakam N, Treasure J (2013). A review of cognitive neuropsychiatry in the taxonomy of eating disorders: state, trait, or genetic? Cognitive Neuropsychiatry 18, 83–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, Demler O, Faraone S, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Jin R, Secnik K, Spencer T, Ustun TB, Walters EE (2005). The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychological Medicine 35, 245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AA, Jacobson KC, Gardner CO, Prescott CA, Kendler KS (2005). Personality and comorbidity of common psychiatric disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry 186, 190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD, Karila L, Billieux J (2014). Internet addiction: a systematic review of epidemiological research for the last decade. Current Pharmaceutical Design 20, 4026–4052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara DR, Akiskal HS (2006). Toward an integrative model of the spectrum of mood, behavioral and personality disorders based on fear and anger traits: II. Implications for neurobiology, genetics and psychopharmacological treatment. Journal of Affective Disorders 94, 89–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lijffijt M, Kenemans JL, Verbaten MN, van Engeland H (2005). A meta-analytic review of stopping performance in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: deficient inhibitory motor control? Journal of Abnormal Psychology 114, 216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan GD, Cowan WB, Davis KA (1984). On the ability to inhibit simple and choice reaction time responses: a model and a method. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance 10, 276–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Weafer J, C Gray J, Oshri A, Palmer A, de Wit H (2016). The latent structure of impulsivity: impulsive choice, impulsive action, and impulsive personality traits. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 233, 3361–3370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malloy-Diniz L, Fuentes D, Leite WB, Correa H, Bechara A (2007). Impulsive behavior in adults with attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder: characterization of attentional, motor and cognitive impulsiveness. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 13, 693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL, Pope HG Jr., Keck PE Jr., Hudson JI, Phillips KA, Strakowski SM (1996). Are impulse-control disorders related to bipolar disorder? Comprehensive Psychiatry 37, 229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda SA, Stevens MC, Potenza MN, Pittman B, Gueorguieva R, Andrews MM, Thomas AD, Muska C, Hylton JL, Pearlson GD (2009). Investigating the behavioral and self-report constructs of impulsivity domains using principal component analysis. Behavioural Pharmacology 20, 390–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montigny C, Castellanos-Ryan N, Whelan R, Banaschewski T, Barker GJ, Buchel C, Gallinat J, Flor H, Mann K, Paillere-Martinot ML, Nees F, Lathrop M, Loth E, Paus T, Pausova Z, Rietschel M, Schumann G, Smolka MN, Struve M, Robbins TW, Garavan H, Conrod PJ, Consortium I (2013). A phenotypic structure and neural correlates of compulsive behaviors in adolescents. PLoS ONE 8, e80151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CF, Sabino V, Koob GF, Cottone P (2017). Pathological overeating: emerging evidence for a compulsivity construct. Neuropsychopharmacology 42, 1375–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray AL, Johnson W (2013). The limitations of model fit in comparing the bi-factor versus higher-order models of human cognitive ability structure. Intelligence 41, 407–422. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B (2016). Mplus User's Guide. Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pallanti S, DeCaria CM, Grant JE, Urpe M, Hollander E (2005). Reliability and validity of the pathological gambling adaptation of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (PG-YBOCS). Journal of Gambling Studies 21, 431–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelis C, Barber FZ, Barnes TR, Nelson HE, Owen AM, Robbins TW (1999). Comparison of set-shifting ability in patients with chronic schizophrenia and frontal lobe damage. Schizophrenia Research 37, 251–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES (1995). Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology 51, 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perpina C, Segura M, Sanchez-Reales S (2016). Cognitive flexibility and decision-making in eating disorders and obesity. Eating and Weight Disorders [epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2016). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria: (https://www.R-project.org/). [Google Scholar]

- Raftery AE (1995). Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological Methodology 25, 111–163. [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP (2012). Invited paper: the rediscovery of bifactor measurement models. Multivariate Behavioral Research 47, 667–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW (2005). Chemistry of the mind: neurochemical modulation of prefrontal cortical function. Journal of Comparative Neurology 493, 140–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, Gillan CM, Smith DG, de Wit S, Ersche KD (2012). Neurocognitive endophenotypes of impulsivity and compulsivity: towards dimensional psychiatry. Trends I Cognitive Science 16, 81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RD, Everitt BJ, Baldacchino A, Blackshaw AJ, Swainson R, Wynne K, Baker NB, Hunter J, Carthy T, Booker E, London M, Deakin JF, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW (1999). Dissociable deficits in the decision-making cognition of chronic amphetamine abusers, opiate abusers, patients with focal damage to prefrontal cortex, and tryptophan-depleted normal volunteers: evidence for monoaminergic mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology 20, 322–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanavio E (1988). Obsessions and compulsions: the Padua Inventory. Behaviour Research and Therapy 26, 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz GE (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Seixas M, Weiss M, Muller U (2012). Systematic review of national and international guidelines on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Psychopharmacology 26, 753–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59(Suppl 20), 22–33; quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon V, Czobor P, Balint S, Meszaros A, Bitter I (2009). Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry 194, 204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford MS, Mathias CW, Dougherty DM, Lake SL, Anderson NE, Patton JH (2016). Fifty years of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale: an update and review. Personality and Individual Differences 47, 385–395. [Google Scholar]

- Stein DJ, Hollander E, Liebowitz MR (1993). Neurobiology of impulsivity and the impulse control disorders. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 5, 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Lijffijt M, Lane SD, Steinberg JL, Moeller FG (2009). Trait impulsivity and response inhibition in antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research 43, 1057–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Steinberg JL, Lijffijt M, Moeller FG (2008). Impulsivity: differential relationship to depression and mania in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 106, 241–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenconi E, Santonastaso P, Degortes D, Bosello R, Titton F, Mapelli D, Favaro A (2010). Set-shifting abilities, central coherence, and handedness in anorexia nervosa patients, their unaffected siblings and healthy controls: exploring putative endophenotypes. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 11, 813–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure J, Cardi V, Leppanen J, Turton R (2015). New treatment approaches for severe and enduring eating disorders. Physiology & Behavior 152, 456–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Heuvel OA, Remijnse PL, Mataix-Cols D, Vrenken H, Groenewegen HJ, Uylings HB, van Balkom AJ, Veltman DJ (2008). The major symptom dimensions of obsessive-compulsive disorder are mediated by partially distinct neural systems. Brain 132, 853–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanheule S, Desmet M, Groenvynck H, Rosseel Y, Fontaine J (2008). The factor structure of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: an evaluation. Assessment 15, 177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veale DM, Sahakian BJ, Owen AM, Marks IM (1996). Specific cognitive deficits in tests sensitive to frontal lobe dysfunction in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychological Medicine 26, 1261–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wareham JD, Potenza MN (2010). Pathological gambling and substance use disorders. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 36, 242–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins LH, Sahakian BJ, Robertson MM, Veale DM, Rogers RD, Pickard KM, Aitken MR, Robbins TW (2005). Executive function in Tourette's syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychological Medicine 35, 571–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K (2009). Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsycholology & Behavior 1, 237–244. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002185.

click here to view supplementary material