Abstract

In this data article, monthly records (datasets) of total delivery, normal delivery, delivery through Caesarean section and number of still births from pregnant women in Akure, the capital city of Ondo state Nigeria, for a period of ten years, between January 2007 and December 2016 were considered. Correlational and time series analyses were conducted on the monthly records of total delivery, normal delivery (delivery through woman virginal), delivery through Caesarean section, and number of still births, in order to observe the patterns each of these indicators follows and to recommend appropriate model for forecasting their future values. The data were obtained in raw form from State Specialist Hospital (SSH), Akure, Ondo state, Nigeria. A clear description and variation in each of these indicators (total delivery, normal delivery, caesarean section, and still births) were considered separately using descriptive statistics and box plots. Different models were also proposed for each of these indicators using time series models.

Keywords: ARIMA, Caesarean section, Normal delivery, Data, Still birth, Time series, Akure

Specification Table

| Subject area | Medicine |

| More specific subject area | Child Birth Delivery, epidemiology of delivery patterns, Biostatistics |

| Type of data | Table and figure |

| How data was acquired | Unprocessed secondary data |

| Data format | Processed as Monthly counts from 2007 to 2016 for Four different indicators on Child Birth Delivery |

| Experimental factors | Data obtained from State Specialist Hospital, Akure |

| Experimental features | Computational Analysis: Time Series Analysis, Time plot, ARIMA Models and Correlation Analysis. |

| Data source location | Ondo State Specialist Hospital, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria |

| Data accessibility | All the data are in this data article |

| Software | R Statistical program and Microsoft Excel |

Value of the Data

-

•

The data on total delivery is a good indicator to monitor the population growth over the previous years.

-

•

The data on still birth is a good indicator for the policy makers in the health sector to improve health facilities in the specialist hospitals and encourage pregnant women to attend anti-natal clinic regularly for necessary medical check-up.

-

•

Data on still birth is also an indicator to create good access to maternal healthcare for all pregnant women at low or no cost.

-

•

Data on still birth can be used to obtain still birth rate (SBR), post neonatal mortality rate (PNMR) and perinatal mortality rate (PMR) of a state or locality.

-

•

Data on Caesarea Section is a good indicator for the government to encourage all pregnant women with any form of challenges on normal delivery to opt for Caesarea section with low or no cost in specialist hospitals.

-

•

The data are for educational purposes and health assessment studies for example gynaecology, obstetrics, nursing and so on.

-

•

The data on normal delivery can as well give a picture of whether there was improvement in the maternal healthcare in the previous years or not.

-

•

The data is useful in the study of epidemiology of child delivery, computational gynaecology and public health studies.

-

•

Several known models for example simple regression and probability fit can be applied to the data which provides alternative to analysis with time series. For example the use of linear, logistic or Poisson regression.

1. Data

The data for this paper was obtained from Ondo State Specialist Hospital, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria. The data are on monthly total delivery, normal delivery, still birth, and delivery by Caesarean Section of pregnant women in the government owned State Specialist Hospital Akure, the capital city of Ondo State, for ten years; between January 2007 and December 2016.

Statistical summary of the monthly averages for each of the indicators (total delivery, normal delivery, still birth and Caesarean section) from January 2007 to December 2016 was given in Table 1. It was observed that the highest monthly total delivery of 436 were recorded in March 2010, while the highest monthly counts for still birth of 29, were recorded in both January and July 2008. However, in terms of proportion, the highest of 0.08815 (8.82%) were recorded in July 2008. Yearly total still births was 158 in 2007 and reduced to 30 in 2016, which amounts to 81% reduction in ten years. In addition, the highest number of Caesarean section of 64 was recorded in both October 2007 and February 2010.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for the four delivery indicators for pregnant women in Akure.

| Indicators | Minimum | 1st Quartile | Median | Mean | 3rd Quartile | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total delivery | 107.0 | 236.80 | 270.00 | 275.90 | 303.20 | 436.00 |

| Normal delivery | 90.00 | 208.00 | 241.50 | 242.00 | 269.80 | 383.00 |

| Still birth | 1.00 | 2.00 | 4.50 | 7.99 | 12.00 | 29.00 |

| Caesarean section | 7.00 | 25.00 | 33.00 | 33.87 | 41.00 | 64.00 |

Correlational results were shown in Table 2 and the result of the time series analysis is contained in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6.

Table 2.

4×4 correlation matrix for the four indicators.

| Indicators | Total delivery | Normal delivery | Still birth | Caesarean section |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total delivery | 1 | |||

| Normal delivery | 0.98098 | 1 | ||

| Still birth | 0.62108 | 0.64250 | 1 | |

| Caesarean section | 0.60594 | 0.43990 | 0.24032 | 1 |

Table 3.

ARIMA output for total delivery of pregnant women in Akure.

| Model | ARIMA(0,1,1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | MA1 | ||

| Coefficients | −0.6238 | ||

| Standard error | 0.0719 | RMSE | 42.6400 |

| σ2 estimate | 1834 | Log-likelihood | −616.1800 |

| AIC | 1236.3700 | BIC | 1241.9300 |

Table 4.

ARIMA output for normal delivery of pregnant women in Akure.

| Model | ARIMA(0,1,1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | MA1 | ||

| Coefficients | −0.6222 | ||

| Standard error | 0.0713 | RMSE | 37.0900 |

| σ2 estimate | 1399 | Log-likelihood | −599.6000 |

| AIC | 1203.2000 | BIC | 1208.7600 |

Table 5.

ARIMA output for still birth delivery by pregnant women in Akure.

| Model | ARIMA(0,1,1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | MA1 | ||

| Coefficients | −0.6806 | ||

| Standard error | 0.0667 | RMSE | 4.2200 |

| σ2 estimate | 17.9900 | Log-likelihood | −341.1000 |

| AIC | 686.2100 | BIC | 691.7700 |

Table 6.

ARIMA output for delivery of pregnant women through Caesarean section in Akure.

| Model | ARIMA(3,0,0) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | AR1 | AR2 | AR3 | Mean | ||

| Coefficients | 0.1208 | 0.1183 | 0.2057 | 33.9664 | ||

| Standard error | 0.0892 | 0.0935 | 0.0935 | 1.9175 | RMSE | 11.8300 |

| σ2 estimate | 144.7000 | Log-likelihood | −466.8100 | |||

| AIC | 943.6200 | BIC | 957.5500 | |||

The raw monthly data for the aforementioned indicators are presented in Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10.

Table 7.

Total monthly delivery of pregnant women between 2007 and 2016.

| Month/Year | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 350 | 342 | 257 | 425 | 259 | 165 | 270 | 232 | 281 | 255 |

| February | 340 | 335 | 240 | 357 | 191 | 245 | 229 | 216 | 202 | 203 |

| March | 306 | 395 | 303 | 436 | 243 | 223 | 299 | 212 | 266 | 238 |

| April | 340 | 379 | 335 | 372 | 229 | 249 | 292 | 290 | 254 | 270 |

| May | 270 | 353 | 305 | 362 | 107 | 278 | 317 | 236 | 291 | 268 |

| June | 287 | 341 | 390 | 286 | 206 | 260 | 255 | 258 | 268 | 270 |

| July | 357 | 329 | 367 | 296 | 206 | 236 | 237 | 276 | 282 | 276 |

| August | 265 | 281 | 302 | 243 | 170 | 210 | 260 | 262 | 262 | 266 |

| September | 370 | 289 | 316 | 256 | 186 | 286 | 268 | 247 | 290 | 275 |

| October | 353 | 357 | 402 | 277 | 213 | 334 | 298 | 286 | 294 | 298 |

| November | 304 | 283 | 357 | 227 | 215 | 259 | 257 | 196 | 225 | 206 |

| December | 301 | 236 | 252 | 196 | 219 | 223 | 182 | 277 | 232 | 251 |

Table 8.

Total monthly normal delivery of pregnant women between 2007 and 2016.

| Month/Year | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 311 | 316 | 208 | 366 | 240 | 150 | 242 | 202 | 257 | 229 |

| February | 277 | 293 | 229 | 293 | 168 | 213 | 208 | 184 | 181 | 182 |

| March | 296 | 355 | 275 | 383 | 208 | 203 | 263 | 174 | 246 | 210 |

| April | 307 | 332 | 293 | 324 | 200 | 224 | 261 | 255 | 219 | 237 |

| May | 245 | 307 | 252 | 305 | 90 | 239 | 277 | 206 | 256 | 231 |

| June | 278 | 312 | 338 | 256 | 168 | 228 | 211 | 229 | 258 | 243 |

| July | 299 | 306 | 316 | 246 | 167 | 215 | 200 | 233 | 257 | 245 |

| August | 256 | 247 | 252 | 205 | 146 | 188 | 220 | 230 | 238 | 234 |

| September | 317 | 266 | 277 | 216 | 160 | 252 | 226 | 219 | 259 | 239 |

| October | 289 | 314 | 352 | 249 | 189 | 293 | 241 | 246 | 255 | 250 |

| November | 259 | 268 | 309 | 189 | 186 | 222 | 223 | 155 | 192 | 173 |

| December | 252 | 220 | 245 | 174 | 203 | 195 | 159 | 248 | 198 | 223 |

Table 9.

Monthly number of pregnant women still birth between 2007 and 2016.

| Month/Year | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 11 | 29 | 12 | 20 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 3 |

| February | 8 | 23 | 8 | 14 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| March | 18 | 22 | 15 | 17 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3 |

| April | 8 | 22 | 25 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| May | 20 | 21 | 18 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| June | 12 | 28 | 16 | 12 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| July | 19 | 29 | 17 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| August | 8 | 11 | 26 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| September | 8 | 17 | 17 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| October | 13 | 26 | 14 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| November | 18 | 21 | 15 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| December | 15 | 11 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

Table 10.

Monthly number of pregnant women with Caesarean section between 2007 and 2016.

| Month/Year | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 39 | 26 | 49 | 59 | 19 | 15 | 28 | 30 | 24 | 26 |

| February | 63 | 42 | 11 | 64 | 23 | 32 | 21 | 32 | 21 | 21 |

| March | 10 | 40 | 28 | 53 | 35 | 20 | 36 | 38 | 20 | 28 |

| April | 33 | 47 | 42 | 48 | 29 | 25 | 31 | 35 | 35 | 33 |

| May | 25 | 46 | 53 | 57 | 17 | 39 | 40 | 30 | 35 | 37 |

| June | 9 | 29 | 52 | 30 | 38 | 32 | 44 | 29 | 10 | 27 |

| July | 58 | 23 | 51 | 50 | 39 | 21 | 37 | 43 | 25 | 31 |

| August | 9 | 34 | 50 | 38 | 24 | 22 | 40 | 32 | 24 | 32 |

| September | 53 | 23 | 39 | 40 | 26 | 34 | 42 | 28 | 31 | 36 |

| October | 64 | 43 | 50 | 28 | 24 | 41 | 57 | 40 | 39 | 48 |

| November | 45 | 15 | 48 | 38 | 29 | 37 | 34 | 41 | 33 | 33 |

| December | 49 | 16 | 7 | 22 | 16 | 28 | 23 | 29 | 34 | 28 |

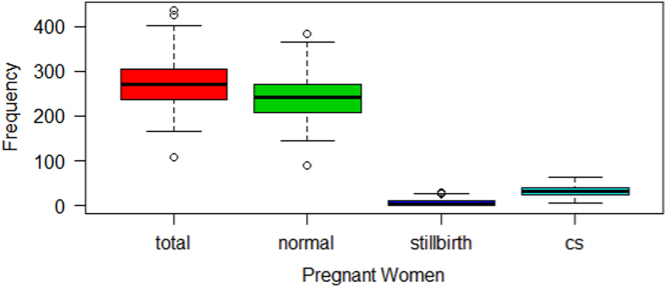

The boxplot in Fig. 1 gives the description and variation in each of the indicators examined in this work. It shows that total and normal deliveries are very close to one another, as well as still birth and caesarean section. The boxplot is a chart presentation of Table 1, with extreme cases of delivery, evident from the outliers above and below each box representing the indicators, except for caesarean section (CS), which possesses no outlier.

Fig. 1.

Boxplot for the four indicators on delivery of pregnant women in Akure.

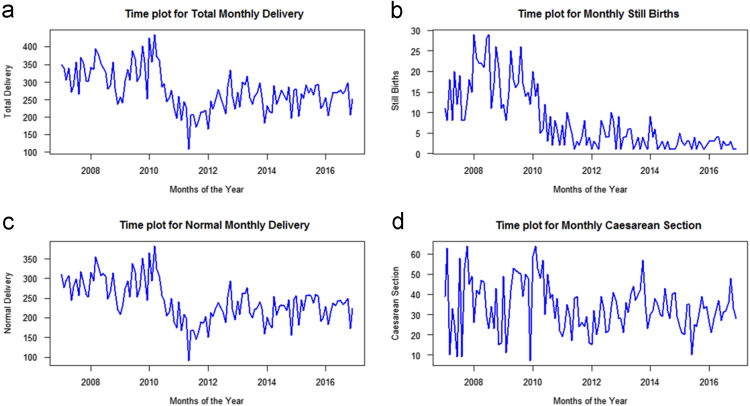

Time Plot for each of the indicators in this paper is presented in Fig. 2a, b, c and d. This is designed to reveal the patterns observed in the given time interval.It can be observed from Fig. 2a and c that the total monthly and normal deliveries of pregnant women across the years under consideration were almost the same pattern.

Fig. 2.

Time plots showing delivery states of pregnant women in Akure between 2007 and 2016.

The progression of pregnant women having still births, dropped drastically when compared with past years (2007–2009) as shown in Fig. 2a, b, c. The focus is on the trend and not on the year's interval.

Between 2014 and 2016, a steady trend was observed, which was stationary. This obviously resulted to the series being constant over studied time frame (period). In Fig. 2d, a trend surfaces between 2010 and 2016 which declines in the first month of every year. Furthermore, the number of pregnant women who underwent Caesarean section, from 2008 to 2016 is evidently declining, which could likely indicate the increasing fear of pregnant women and most especially the cost of being subjected to such mode of delivery.

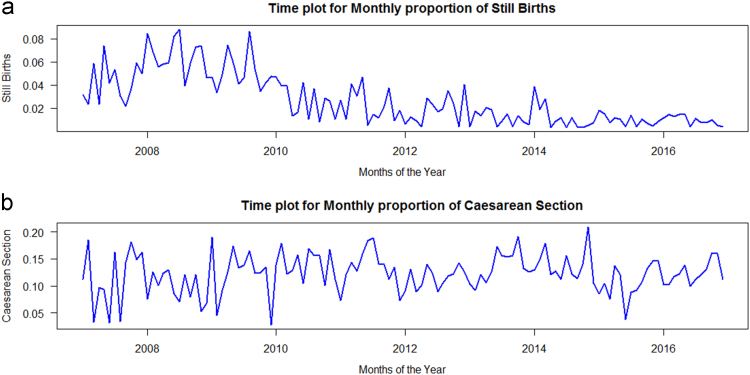

It was observed from Fig. 3a, that the proportion of still birth dropped drastically towards year 2016, when compared with the first two or three years under consideration, that is from 2007 to 2009. It was also observed that, the total number of still births in year 2016 (30) was almost the same as the highest monthly (29) earlier recorded in both January and July 2008 respectively. This may be attributed to government efforts in the state to improve maternal and child healthcare is yielding dividends which eventually reduced the rate of monthly still birth in the state to the point of one or even zero as times goes on. The differences in the proportion of pregnant women undergoing Caesarean section across the years under investigation are not significant in pattern as seen in Fig. 3b. Furthermore, the plot showed that within 15.00% to 20.00% of the total number of pregnant women deliver through Caesarean section yearly and within these years drop to as low as 5.00%.

Fig. 3.

Monthly proportion for still birth and Caesarean delivery by pregnant women in Akure between 2007 and 2016.

2. Methods and materials

Several studies have been conducted on the issues affecting normal delivery, still birth incidences and epidemiology of Caesarean section child delivery among women in Nigeria [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. Similar data articles on medicine that applied statistical tools could be helpful, readers are refer to [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29].

Correlation and time series tools are used to explore the data of child delivery in Akure, Nigeria. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for the each pairs of total delivery, normal delivery, still birth and Caesarean section. Furthermore, autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) was used in describing and modeling the pattern of child delivery. The correlation was done using the Microsoft Excel while the time series analysis was done with the aid of the R software.

2.1. Correlational study

The correlation coefficient shows the degree of linear relationship that exists between two variables; this was presented in Table 2. There is a very high correlation between total and normal delivery (0.98098), followed by normal delivery and still birth (0.64250), while the least is between Caesarean section and still birth (0.24032).

2.2. Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA)

ARIMA is a time series statistical tool used in describing and modeling the pattern of a given seasonal and non-seasonal time series data. Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 present the appropriate ARIMA models for each of the indicators under consideration. It was observed that ARIMA (0, 1, 1) is best for describing and forecasting the future counts for three of the indicators: total delivery, normal delivery and still birth, while ARIMA (3, 0, 0) is most appropriate for the number of delivery through Caesarean section.

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by Centre for Research, Innovation and Discovery, Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria. Also the authors thank the management of State Specialist Hospital, Akure, for making the data available.

Footnotes

Transparency data associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2017.11.041.

Transparency document. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Oluwafemi R.O., Abiodun M.T. Incidence and outcome of preterm deliveries in Mother and Child Hospital Akure, Southwestern Nigeria. Sri Lanka J. Child Health. 2016;45(1):11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawan U.M., Takai I.U., Ishaq H. Perceptions about eclampsia, birth preparedness, and complications readiness among antenatal clients attending a specialist hospital in Kano, Nigeria. J. Trop. Med. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/431368. (Article number 431368) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebuehi O.M., Akintujoye I.A. Perception and utilization of traditional birth attendants by pregnant women attending primary health care clinics in a rural Local Government Area in Ogun State, Nigeria. Int. J. Women Health. 2012;4(1):25–34. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S23173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azuh D.E., Azuh A.E., Iweala E.J., Adeloye D., Akanbi M., Mordi R.C. Factors influencing maternal mortality among rural communities in southwestern Nigeria. Int. J. Women. Health. 2017;9:179–188. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S120184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muhammad H.U., Giwa F.J., Olayinka A.T., Balogun S.M., Ajayi I., Ajumobi O., Nguku P. Malaria prevention practices and delivery outcome: a cross sectional study of pregnant women attending a tertiary hospital in northeastern Nigeria. Malar. J. 2016;15(1) doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1363-x. (Article 326) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tukur I., Cheekhoon C., Tinsu T., Muhammed-Baba T., Aderemi Ijaiya M. Why women are averse to facility delivery in Northwest Nigeria: a qualitative inquiry. Iran. J. Public Health. 2016;45(5):586–595. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wollum A., Burstein R., Fullman N., Dwyer-Lindgren L., E. Gakidou E. Benchmarking health system performance across states in Nigeria: a systematic analysis of levels and trends in key maternal and child health interventions and outcomes, 2000–2013. BMC Med. 2015;13(1) doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0438-9. (Article 208) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawani L.O., Eze J.N., Anozie O.B., Iyoke C.A., N.N. Ekem N.N. Obstetric analgesia for vaginal birth in contemporary obstetrics: a survey of the practice of obstetricians in Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-140. (Article 140) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ronsmans C., Holtz S., Stanton C. Socioeconomic differentials in caesarean rates in developing countries: a retrospective analysis. Lancet. 2006;368(9546):1516–1523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69639-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawn J.E. Stillbirths: where? When? Why? How to make the data count? Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1448–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abiodun O.O., Francis B. Factors associated with spontaneous preterm delivery in a Nigerian Teaching Hospital. Bangladesh. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016;29(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nwankwo T.O., Aniebue U.U., Ezenkwele E., Nwafor M.I. Pregnancy outcome and factors affecting vaginal delivery of twins at University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2013;16(4):490–495. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.116895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erim D.O., Kolapo U.M., Resch S.C. A rapid assessment of the availability and use of obstetric care in Nigerian healthcare facilities. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fleming V., Meyer Y., Frank F., Gogh S.V., Schirinzi L., Michoud B., de Labrusse C. Giving birth: expectations of first time mothers in Switzerland at the mid point of pregnancy. Women Birth. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.04.002. (In Press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zgheib S.M., Kacim M., Kostev K. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with cesarean section in Lebanon — A retrospective study based on a sample of 29,270 women. Women Birth. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.05.003. (In Press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koshida S., Ono T., Tsuji S., Murakami T., Arima H., Takahashi K. Excessively delayed maternal reaction after their perception of decreased fetal movements in stillbirths: population-based study in Japan. Women Birth. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.04.005. (In Press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.S. Wickham, Appraising Research into Childbirth – 1st Edition, 2006.

- 18.Homer C.S.E., Leap N., Edwards N., Sandall J. Midwifery continuity of carer in an area of high socio-economic disadvantage in London: a retrospective analysis of Albany Midwifery Practice outcomes using routine data (1997–2009) Midwifery. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.02.009. (In Press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.T.O. Takpor, A.A. Atayero, Advances in current techniques for monitoring the progress of child delivery, Lecture Notes in Engineering and Computer Science, volume 2, 2014, pp. 781–784. World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science 2014, WCECS 2014, San Francisco, United States, 22 October 2014 through 24 October 2014.

- 20.Lobysheva I.I., van Eeckhoudt S., Dei Zotti F., Rifahi A., Pothen L., Beauloye C., Balligand J.L. Clinical and biochemical characterization of endothelial function in women consuming combined contraceptives. Data Brief. 2017;13:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingoglia G. Data demonstrating the anti-oxidant role of hemopexin in the heart. Data Brief. 2017;13:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roubille F. Data on nation-wide activity in Intensive Cardiac Care Units in France in 2014. Data Brief. 2017;13(2017):166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan Z., Zhao J., Liu J., Zhang M., Chen R., Xie K., Dai J. Data on eleven sesquiterpenoids from the cultured mycelia of Ganoderma capense. Data Brief. 2017;12:361–363. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panieri E., Santoro M.M. Data on metabolic-dependent antioxidant response in the cardiovascular tissues of living zebrafish under stress conditions. Data Brief. 2017;12:427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Satagopan J.M., Iasonos A., Kanik J.G. A reconstructed melanoma data set for evaluating differential treatment benefit according to biomarker subgroups. Data Brief. 2017;12:667–675. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zyubin A., Lavrova A., Demin M., Pankina A., Babak S. The data obtained during the analysis of clinical blood samples for children acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients with severe side-effects. Data Brief. 2017;11:522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adejumo A.O., Ikoba N.A., Suleiman E.A., Okagbue H.I., Oguntunde P.E., Odetunmibi O.A., Job O. Quantitative exploration of factors influencing psychotic disorder ailments in Nigeria. Data Brief. 2017;14:175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King P.L., Troitzsch U., Jones T. Characterization of mineral coatings associated with a Pleistocene‐Holocene rock art style: the Northern running figures of the East Alligator River region, western Arnhem Land, Australia. Data Brief. 2017;10:537–543. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2016.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oguntunde P.E., Adejumo A.O., Okagbue H.I. Breast cancer patients in Nigeria: data exploration approach. Data Brief. 2017;15:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material