Abstract

Background

Optimal graft versus host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis prevents severe manifestations without excess immunosuppression. Standard prophylaxis includes a calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) with low-dose methotrexate. However, single-agent CNI may be sufficient prophylaxis for a defined group of patients. Single-agent CNI has been used for GVHD prophylaxis for human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched sibling donor (MSD) bone marrow transplants (BMTs) in young patients at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for over 20 years. Here, we describe outcomes using this prophylactic strategy in a recent cohort.

Procedure

We performed a single-institution chart review and retrospective analysis of consecutive children undergoing MSD BMT who received single-agent CNI for GVHD prophylaxis between January 2002 and December 2014.

Results

Fifty-two children with a median age of 6.1 years (interquartile range [IQR] 2.5–8.3) and donor age of 6 years (IQR 3–10), with malignant and nonmalignant diseases (n = 35 and 17, respectively) were evaluated. Forty-three (82.6%) received oral prophylaxis with single-agent tacrolimus after initial intravenous therapy. Rates of GVHD were consistent with reported rates on dual prophylaxis: the overall incidence of grades 2–4 acute GVHD was 25.5%, grades 3–4 GVHD 9.8%, and chronic GVHD 10.4%. The cumulative incidence of relapse among children with malignancy was 20% at a median of 237 days (IQR 194–318) post-transplant. Two-year overall survival was 82.7% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 69.4–90.6%) and event-free survival was 78.9% (95% CI: 65.1–87.7%). No patient experienced graft failure.

Conclusions

Single-agent CNI is a safe, effective approach to GVHD prophylaxis in young patients undergoing HLA-identical sibling BMT. Additionally, single-agent oral tacrolimus is a reasonable alternative to cyclosporine in this population.

Keywords: BMT, calcineurin inhibitor, graft versus host disease, matched sibling donor BMT, pediatric hematology/oncology, tacrolimus

1 INTRODUCTION

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a potentially curative option for patients with hematologic malignancies, bone marrow failure syndromes, primary immunodeficiencies, and hemoglobinopathies. Graft versus host disease (GVHD) remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality and occurs in as many as half of allogeneic HSCT recipients.1 Currently, the most common pharmacologic prophylactic regimen to prevent GVHD is a calcineurin inhibitor (CNI), either cyclosporine A (CSA) or tacrolimus, in conjunction with methotrexate (MTX), administered as three or four doses in the first 2-weeks post-transplant.2–4 This regimen is based on studies that demonstrated improved survival compared to those who received either agent alone.5–8

However, the inclusion of MTX as a second agent is associated with increased mucosal and hepatic toxicity, delayed engraftment, and increased infectious risk.2,5,9 Moreover, when employing HSCT for the treatment of hematologic malignancies, several studies have demonstrated that acute GVHD is associated with a decreased risk of leukemic relapse, and has a positive impact on leukemia-free survival due to a graft-versus-leukemia effect.10–12 Thus, in these cases, the ideal GVHD prophylactic regimen should effectively prevent severe GVHD while avoiding excess immunosuppression that might contribute to relapse or toxicity.

In general, pediatric patients have a lower incidence and decreased severity of GVHD than their adult counterparts and may warrant a less intensive approach to prophylaxis.6,13 There is early evidence to suggest that single-agent prophylaxis may be sufficient for the prevention of GVHD in patients undergoing transplantation for malignant indications and that less immunosuppression has a positive impact on event-free survival.9,14–17 There are less data on the use of single-agent GVHD prophylaxis in patients undergoing HLA-matched sibling donor (MSD) HSCT for nonmalignant indications, particularly the use of single-agent tacrolimus. We hypothesized that GVHD prophylaxis with single-agent CNI would be safe and effective in pediatric patients undergoing MSD bone marrow transplant (BMT), particularly when both recipient and donor are young. This descriptive study contributes to the literature on the optimal pharmacologic GVHD prophylaxis in children.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

We identified a retrospective cohort of consecutive pediatric patients who underwent first MSD BMT for any indication between 2002 and 2014 at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and performed a manual review of their records. As per the institutional standards, since 2004 all patients less than 14 years with donors less than 14 years undergoing MSD BMT received a single-agent CNI for GVHD prophylaxis. The age determination was arbitrary, but based on the studies that showed higher risk of GVHD in older teens.18–20 This study was approved by the CHOP Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent.

2.2 Conditioning regimen

Conditioning regimen was chosen based on the best available evidence at the time of transplant. Among patients with malignancy, the pretransplant conditioning regimen included cyclophosphamide (200 mg/kg) with total body irradiation (TBI) (1,200 cGy) and thiotepa (120 mg/kg) for 15 (42.9%) patients and cyclophosphamide with busulfan (target AUC 900–1,500 μmol min/l) for 20 (57.1%) patients. Patients with immunodeficiency and hemoglobinopathy were conditioned with busulfan and cyclophosphamide as above and patients with severe aplastic anemia (sAA) were conditioned with a reduced intensity regimen that included cyclophosphamide alone with the addition of fludarabine (150 mg/kg) in two cases.

A subset of patients received thymoglobulin (ATG) 3 mg/kg/day for 3 days to prevent graft rejection, including all patients with sAA, two patients with primary immunodeficiency, a single patient with hemoglobinopathy, and one patient with myelodysplastic syndrome. Patients received steroid premedication with ATG infusions that completed 48 hr after ATG (prior to the start of transplant).

2.3 GVHD prophylaxis

As per institution standards, CSA or tacrolimus is administered as a continuous infusion from day −1 and patients are transitioned to an oral CNI twice daily once oral administration can be tolerated. In most cases, tacrolimus was the preferred oral CNI at CHOP due to its more favorable side effect profile with decreased hirsutism and gingival hyperplasia. Doses were adjusted to target through levels of 300–400 ng/ml for CSA and 5–10 ng/ml for tacrolimus. In patients with malignant disease without evidence of GVHD, the oral medication was tapered 10–20% weekly beginning 100 days post-transplant. For those with nonmalignant disease, the taper began on days 150–180 post-transplant.

2.4 Statistical analysis and study endpoint definitions

The following data were included for description and analysis: (i) demographic information, (ii) donor age and sex, (iii) transplant-related variables including indication for transplant and conditioning regimen, (iv) agents and duration of prophylaxis for GVHD, (v) development and maximum grade of GVHD, (vi) engraftment kinetics, (vii) relapse, and (viii) mortality and cause of death.

Acute GVHD was graded by standard clinical criteria and staged according to the Glucksberg criteria, and was collected as maximum documented grade prior to day +100 post-transplant.21 Chronic GVHD was diagnosed and staged according to the Seattle clinical grading and staging system and was captured if documented anytime in 2 years post-transplant.22 Biopsies were obtained when clinically indicated, but were not required for a patient to be determined to have acute or chronic GVHD.

Transplant-related mortality (TRM) was defined as any nonrelapse cause of death after BMT. Engraftment of neutrophils and platelets was defined as the first of three consecutive days with an absolute neutrophil count >0.5 × 109/l and unsupported platelet count >20 × 109/l.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata/1C (version 14.2 for Mac). Patient characteristics were summarized with descriptive statistics using percentages for categorical variables and median and range or interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. Comparisons between groups of patients were made using logistic regression, Pearson’s χ2 or Mann–Whitney test as applicable. The Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test were used for survival or probability estimates. A P-value of 0.05 was considered significant. Patients who died prior to 21 days post-transplant were excluded from all GVHD analyses; those who died or relapsed prior to 100 days post-transplant were excluded from chronic GVHD analyses.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study population

The cohort comprised 52 children who underwent MSD BMT. No patient was lost to follow-up; all patients had data for 2 years post-transplant. Patient characteristics are described in Table 1. Due to a change in institutional standards in 2004, only four patients and two donors were more than 14 years of age at the time of transplantation. Patients received stem cells from bone marrow with a mean cell dose of 3.1 × 108 nC/kg.

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

| Age at transplant in years, median (range) | 6.1(0.2–18.1) |

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 21 (40.4%) |

| Donor age in years, median (range) | 6 (0.4–14) |

| Female donor, n (%) | 25 (48.1%) |

| Sex match (recipient/donor) | |

| Matched | 26 (50%) |

| Male/female | 15 (28.9%) |

| Female/male | 11 (21.1%) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Malignanta | 35 (67.3%) |

| AML/MDS | 23 (44.2%) |

| ALL | 10 (19.2%) |

| CML | 1 (1.9%) |

| Nonmalignant | 17 (32.7%) |

| sAA | 11 (21.2%) |

| Primary immunodeficiency | 4 (7.7%) |

| Hemoglobinopathy | 1 (1.9%) |

| HLH | 1 (1.9%) |

| Conditioning, n (%) | |

| Myeloablative | |

| TBI-based | 15 (28.8%) |

| Busulfan-based | 26 (50%) |

| Reduced intensity conditioning | 11(21.2%) |

| Receipt of ATG, n (%) | 15 (28.8%) |

| GVHD prophylaxis, n (%) | |

| CSA → CSA | 6 (11.5%) |

| CSA → Tacrolimus | 42 (80.7%) |

| Tacrolimus → Tacrolimus | 1 (1.9%) |

| IV CSAonlyb | 3 (5.8%) |

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; sAA, severe aplastic anemia; CSA, cyclosporine A.

CR1 = 20, ≥CR2 = 7, MDS = 7.

Patients died prior to transitioning to oral medications.

3.2 GVHD prophylaxis

Most patients received intravenous CSA and transitioned to oral tacrolimus. All the patients who received oral cyclosporine were transplanted prior to 2004, reflecting the institutional change in practice to use oral tacrolimus. Three patients died while still receiving intravenous prophylaxis.

Among patients without GVHD, the median duration of immunosuppression with a CNI was 98 days (IQR 69–124) in patients with malignant transplant indications and 184 days (IQR 107–233) among those with nonmalignant indications. The median duration for the entire cohort was 111 days (IQR 76–183). Several patients did not complete their planned duration of therapy with a CNI. The reasons for stopping therapy with a CNI prior to the planned date were as follows: to aid engraftment in six patients (11.5%), renal toxicity in four patients (7.7%), relapse in one patient (1.9%), infection in one patient (1.9%), and death in three patients (5.8%). There was no significant difference in length of time on oral medication between tacrolimus and CSA (median 111 days vs. 168.5 days, P = 0.47).

3.3 GVHD

The incidence of GVHD is shown in Table 2. These rates were similar in a subanalysis by oral agent (Supplementary Table S2). Among patients who did not receive ATG as part of their conditioning, rates of acute GVHD were higher than in the cohort as a whole (29.7%), but rates of chronic GVHD were only 8.1% (Supplementary Table S1).

TABLE 2.

Incidence of GVHD

| Overall | Malignant | Nonmalignant | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute GVHD, n (%) | ||||

| None | 30 (58.8%) | 16 (47%) | 14 (82.4%) | 0.019 |

| Grades 2–4 | 13 (25.5%) | 11 (32.4%) | 2 (11.7%) | 0.18 |

| Grades 3–4 | 5 (9.8%) | 3 (8.8%) | 2 (11.7%) | 1 |

| Chronic GVHD | ||||

| None | 43 (89.6%) | 30 (90.9%) | 13 (86.7%) | 0.642 |

| Limited | 4 (8.3%) | 3 (9.1%) | 1 (6.7%) | 1 |

| Extensive | 1 (2.1%) | 0 | 1 (6.7%) | 0.31 |

| Inevaluablea | 4 (7.7%) | 2 (5.7%) | 2 (11.8%) | – |

Patients who died prior to day 100.

Patients with malignant indications for transplant experienced more GVHD than those without malignancy (odds ratio [OR] 4.96, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.2–20.4). This effect remained, however the association was no longer significant when we controlled for the receipt of ATG (OR 1.66, 95% CI: 0.19–14.7). The loss of significance was likely due to the small sample size and strong collinearity of ATG with nonmalignant indications for transplantation. Otherwise there were no statistically significant predictors of GVHD including recipient or donor age, sex concordance between donor and recipient, or conditioning.

3.4 Hematopoietic recovery (Table 3)

TABLE 3.

Engraftment kinetics, relapse, and mortality

| Overall | Malignant | Nonmalignant | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days of initial hospitalization, median (IQR) | 23.5 (21.5–28.5) | 22 (21–26) | 25 (22–34) | 0.10 |

| Days to engraftment, median (IQR) | ||||

| Neutrophils | 18 (14–22) | 18 (16–20) | 17 (14–22) | 0.77 |

| Platelets | 24 (20–32) | 23.5 (19–27) | 27 (22–35) | 0.14 |

| Relapse | – | 7 (20%) | – | – |

| Days to relapse, median (range) | – | 237.5 (110–496) | – | – |

| Death | 9 (17.3%) | 7 (20%) | 2 (11.7%) | 0.7 |

| Days to death, median (range) | 191 (15–600) | 237.5 (110–496) | 70.5 (64–77) | 0.24 |

| Transplant-related mortality (TRM) | 4 (7.7%) | 2 (5.7%) | 2 (11.8%) | 0.59 |

| Days to TRM, median (range) | 70 (15–77) | 76 (15–77) | 70.5 (64–77) | 0.44 |

| Relapse-related | 5 (9.6%) | 5 (14.3%) | – | – |

| Days to death, median (range) | 375 (191–600) | 375 (191–600) | – | – |

| Other clinical complications, n (%) | ||||

| Venoocclusive disease of the liver | 4 (7.7%) | 2 (5.7%) | 2 (11.8%) | 0.589 |

| Bleeding | 3 (5.8%) | 2 (5.7%) | 1 (5.9%) | 1 |

| Transplant-associated microangiopathy | 2 (3.8%) | 1 (2.9%) | 1 (5.9%) | 1 |

Median times to engraftment were 18 days (IQR 14–22) for neutrophils and 24 days (IQR 20–32) for platelets; this was similar for both malignant and nonmalignant subgroups. All patients engrafted their neutrophils by 31 days post-transplant. Of those who engrafted their platelets (n = 49), all did so by 61 days post-transplant; three patients died prior to platelet engraftment. No patient experienced primary or secondary graft failure.

3.5 Relapse and mortality

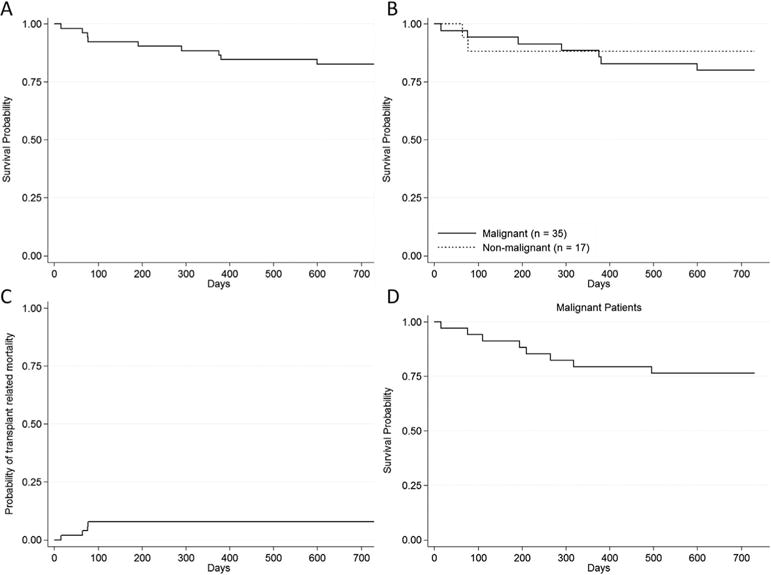

Two-year overall survival (OS) was 82.7% (95% CI: 69.4–90.6%, Fig. 1A) and event-free survival was 78.9% (95% CI: 65.1–87.7%); OS for patients with malignant and nonmalignant conditions was 80.0% and 88.3%, respectively (Fig. 1B, log-rank test P = 0.50). TRM occurred in four patients, all less than 100 days post-transplant: three from venoocclusive disease of the liver and one from infection. Five patients relapsed at a median of 237 days post-transplant (IQR 194–318), with a cumulative incidence of relapse of 20%. The TRM and relapse curves are shown in Figures 1C and 1D, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Estimated survival: (A) overall cumulative survival for all patients; (B) overall survival of patients with malignant disease versus patients with nonmalignant disease; (C) probability of TRM for all patients; (D) probability of relapse for patients with malignant disease

4 DISCUSSION

The primary objective of this retrospective study was to evaluate the efficacy of single-agent prophylaxis for prevention of GVHD in pediatric patients undergoing MSD BMT. Data from prospective randomized trials in adults have demonstrated that dual prophylaxis with CSA and MTX leads to lower incidence and decreased severity of GVHD than in those receiving CSA alone.5,23 However, these studies do not include pediatric patients. Because young age is associated with lower rates of GVHD, the optimal degree of immunosuppression to prevent GVHD while minimizing toxicity, risk of infection, and relapse rates in these lower risk patients is not fully understood.6,7,18 Our data demonstrate that a CNI alone effectively prevents severe GVHD in this population: the overall incidence of grades 2–4 acute GVHD and chronic GVHD in this cohort were comparable to those reported in studies of children using dual prophylactic regimens.2,12,24–27

Results of the phase three randomized trial ASCT0431 demonstrate that among pediatric patients transplanted for acute leukemia, acute GVHD is significantly associated with improved event-free survival and a decreased rate of relapse.12 In contrast, chronic GVHD is associated with significant morbidity and is the primary factor associated with poor quality of life post-transplant.28,29 Therefore, for patients with malignant conditions, the goal of a GVHD prophylactic strategy is to prevent extensive chronic GVHD but allows for mild to moderate acute and chronic GVHD.30,31

A few studies have used single-agent prophylaxis in pediatric patients with a malignant indication for transplant to maximize a graft-versus-leukemia effect. The Children’s Cancer Group study 2891 leveraged a single-agent strategy in 150 children with acute myeloid leukemia undergoing MSD BMT. Using single-agent MTX as prophylaxis, they found overall low rates of severe acute GVHD, especially in children younger than 10 years in whom the rate of grades 3–4 acute GVHD was only 4.6%. However, the rate of chronic GVHD was 21.3%.31 Koga et al. prospectively compared single-agent MTX to single-agent CSA in a small, heterogeneous cohort of patients and found similar rates of GVHD and relapse in both groups. Overall grades 2–4 GVHD occurred in one-third of patients and chronic GVHD in 20%.14

More recently, Bleyzac et al. described a single-agent CSA approach to immunosuppression in 109 children with acute leukemia that resulted in 30% of patients with acute GVHD and much lower rates of chronic GVHD (8.2%).16 Additionally, Weiss et al. compared CSA alone in 16 children with leukemia to a historical control group that received CSA with MTX and found similar rates of acute and chronic GVHD in the two groups, but improved 5-year event-free survival in patients who received single-agent CSA compared to those who received dual prophylaxis (85% vs. 42%).17

In the current study, which included 35 children with malignant indications for transplantation, the rate of grades 2–4 acute GVHD (32.4%) is acceptable given the very low rates of grades 3–4 acute GVHD and chronic GVHD (8.8% and 9.1%, respectively). The low rate of relapse in patients with malignancy may be partially attributable to the rate of grades 1–2 acute GVHD observed in these patients (44.2%). These results contribute to this new body of data suggesting that single-agent prophylaxis with a CNI is adequate for the prevention of severe GVHD in young children and donors and may improve relapse-free survival.

Among those with nonmalignant indications for transplant, who do not stand to benefit from the graft-versus-leukemia effect, rates of GVHD were lower than those transplanted for malignancy. Age and frequency of sex concordance between recipient and donor were similar between malignant and nonmalignant patients, however nonmalignant patients received prophylactic immunosuppression for a longer duration. In addition, the majority of the nonmalignant patients received lymphodepleting serotherapy with ATG as part of conditioning to facilitate engraftment. The inclusion of this agent contributed to the lower rates of GVHD in the patients without malignancy.24,32,33

In the subset of patients with sAA, no patient (0/11) developed GVHD. Moreover, among this cohort, no patient died or experienced graft failure. Reported rates of GVHD in sAA range from 0% to 60% and utilize a variety of multiagent GVHD prophylactic strategies.34–37 A single prospective study has compared single-agent CNI to combination therapy with MTX in both adults and children with aplastic anemia and found similar rates of acute GVHD in the two groups (30% vs. 38%).38 Compared to this study, the sAA patients in our cohort had a lower median age (8 years compared to 18 years) and received ATG, both of which may account for the much lower rates of GVHD that we found. Though the sample size is small, the results described here suggest that more study is warranted, and less immunosuppression may suffice to facilitate engraftment and prevent GVHD in children with sAA.

There are no published data on the use of single-agent prophylaxis in patients with primary immunodeficiencies, hemoglobinopathies, or hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; however, there were so few patients transplanted for these indications in our cohort that we are unable to generalize our results beyond reporting that this approach was used in this small group.

In contrast to the previously performed analyses of monotherapy in either malignant or nonmalignant cohorts, the majority of the patients in this cohort transitioned to oral tacrolimus upon discharge. This macrolide immunosuppressant, which has a mechanism of action similar to that of cyclosporine, effectively prevents GVHD but has a more favorable side effect profile including less hirsuitism and gingival hyperplasia, and better oral tolerability.39 Since its introduction, tacrolimus has been used in combination therapy for the prevention of GVHD in both malignant and nonmalignant populations.24,35,40,41 The data presented here demonstrate rates of GVHD with tacrolimus monotherapy are comparable to prophylactic regimens that include CSA. More research is needed to understand the best agent and dosing regimen for single-agent therapy.

The OS among those with malignant and nonmalignant diseases was excellent: 79% and 83%, respectively. TRM was clustered toward the earlier years in the cohort (three of four transplant-related deaths occurred from 2002 to 2005), likely reflecting improvements in supportive care over this time frame, particularly the use of defibrotide for the treatment of venoocclusive disease of the liver. No patient experienced graft failure, and all patients engrafted neutrophils by 1 month post-transplant. However, because of the heterogeneity of diagnoses and conditioning intensity, comparison of these metrics to other studies is difficult.

The limitations of this study are due to its retrospective and single-center nature. It includes a heterogeneous group of patients with different underlying diseases and different conditioning regimens. Importantly, the majority of recipients and donors in our study were younger than 14 years old, and results should not be extrapolated beyond this age group.

Our results indicate that a GVHD prophylaxis regimen for MSD BMT based on single-agent CNI in young children with young donors is safe and effective, with rates of GVHD, relapse and graft failure similar to that reported with other prophylactic strategies. Additionally, oral tacrolimus is a reasonable alternative to CSA in this population. Based on the results presented here, consideration should be given to a single-agent approach in pediatric patients with malignancy and those with sAA who also receive ATG as part of their conditioning. Prospective, randomized studies are needed to optimize the use of single-agent CNI prophylaxis, particularly with regards to the oldest age of recipient or donor in which this strategy is appropriate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a training grant from the National Institutes of Health, Clinical Pharmacoepidemiology Training grant, #T32-GM075766 (CWE); an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scientist grant in Applied and Clinical Research, grant number: MRSG-12-215-01-LIB (AES); an Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation Epidemiology Award, grant number: 37553 (AES); and the Richard and Sheila Sanford Endowed Chair in Pediatric Oncology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (AES).

Abbreviations

- ATG

thymoglobulin

- BMT

bone marrow transplant

- CHOP

The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

- CI

confidence interval

- CNI

calcineurin inhibitor

- CSA

cyclosporine A

- GVHD

graft versus host disease

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- HSCT

hematopoietic stem cell transplant

- IQR

interquartile range

- MSD

matched sibling donor

- MTX

methotrexate

- OR

odds ratio

- sAA

severe aplastic anemia

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ferrara JL, Levine JE, Reddy P, Holler E. Graft-versus-host disease. Lancet. 2009;373(9674):1550–1561. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60237-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton BK, Rybicki L, Dean R, et al. Cyclosporine in combination with mycophenolate mofetil versus methotrexate for graft versus host disease prevention in myeloablative HLA-identical sibling donor allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(2):144–148. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watanabe N, Matsumoto K, Yoshimi A, et al. Outcome of bone marrow transplantation from HLA-identical sibling donor in children with hematological malignancies using methotrexate alone as prophylaxis for graft-versus-host disease. Int J Hematol. 2008;88(5):575–582. doi: 10.1007/s12185-008-0211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters C, Minkov M, Gadner H, et al. Statement of current majority practices in graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis and treatment in children. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26(4):405–411. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Storb R, Deeg HJ, Whitehead J, et al. Methotrexate and cyclosporine compared with cyclosporine alone for prophylaxis of acute graft versus host disease after marrow transplantation for leukemia. New Engl J Med. 1986;314(12):729–735. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198603203141201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ringden O, Horowitz MM, Sondel P, et al. Methotrexate, cyclosporine, or both to prevent graft-versus-host disease after HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplants for early leukemia? Blood. 1993;81(4):1094–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin P, Bleyzac N, Souillet G, et al. Clinical and pharmacological risk factors for acute graft-versus-host disease after paediatric bone marrow transplantation from matched-sibling or unrelated donors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32(9):881–887. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holler E. Progress in acute graft versus host disease. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14(6):625–631. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3282f08dd9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JH, Lee JH, Choi SJ, et al. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)-specific survival and duration of systemic immunosuppressive treatment in patients who developed chronic GVHD following allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2003;122(4):637–644. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, Storb R, et al. Influence of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease on relapse and survival after bone marrow transplantation from HLA-identical siblings as treatment of acute and chronic leukemia. Blood. 1989;73(6):1720–1728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ringden O, Hermans J, Labopin M, Apperley J, Gorin NC, Gratwohl A. The highest leukaemia-free survival after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation is seen in patients with grade I acute graft-versus-host disease. Acute and Chronic Leukaemia Working Parties of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Leuk Lymphoma. 1996;24(1–2):71–79. doi: 10.3109/10428199609045715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pulsipher MA, Langholz B, Wall DA, et al. The addition of sirolimus to tacrolimus/methotrexate GVHD prophylaxis in children with ALL: a phase 3 Children’s Oncology Group/Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium trial. Blood. 2014;123(13):2017–2025. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-534297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weisdorf D, Hakke R, Blazar B, et al. Risk factors for acute graft-versus-host disease in histocompatible donor bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation. 1991;51(6):1197–1203. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199106000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koga Y, Nagatoshi Y, Kawano Y, Okamura J. Methotrexate vs cyclosporin A as a single agent for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in pediatric patients with hematological malignancies undergoing allogeneic bone marrow transplantation from HLA-identical siblings: a single-center analysis in Japan. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32(2):171–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Locatelli F, Zecca M, Rondelli R, et al. Graft versus host disease prophylaxis with low-dose cyclosporine-A reduces the risk of relapse in children with acute leukemia given HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation: results of a randomized trial. Blood. 2000;95(5):1572–1579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bleyzac N, Cuzzubbo D, Renard C, et al. Improved outcome of children transplanted for high-risk leukemia by using a new strategy of cyclosporine-based GVHD prophylaxis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51(5):698–704. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss M, Steinbach D, Zintl F, Beck J, Gruhn B. Superior outcome using cyclosporin A alone versus cyclosporin A plus methotrexate for post-transplant immunosuppression in children with acute leukemia undergoing sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141(6):1089–1094. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1885-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisner MD, August CS. Impact of donor and recipient characteristics on the development of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease following pediatric bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15(5):663–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkinson K, Horowitz MM, Gale RP, et al. Risk factors for chronic graft-versus-host disease after HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1990;75(12):2459–2464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kondo M, Kojima S, Horibe K, Kato K, Matsuyama T. Risk factors for chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation in children. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27(7):727–730. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glucksberg H, Storb R, Fefer A, et al. Clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of marrow from HL-A-matched sibling donors. Transplantation. 1974;18(4):295–304. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197410000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man. A long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. Am J Med. 1980;69(2):204–217. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee KH, Choi SJ, Lee JH, et al. Cyclosporine alone vs cyclosporine plus methotrexate for post-transplant immunosuppression after HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation: a randomized prospective study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;34(7):627–636. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Offer KK. Efficacy of tacrolimus/mycophenolate mofetil as acute graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis and the impact of subtherapeutic tacrolimus levels in children after matched sibling donor allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood marrow Transplant. 21(3):496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.11.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eapen M, Horowitz MM, Klein JP, et al. Higher mortality after allogeneic peripheral-blood transplantation compared with bone marrow in children and adolescents: the Histocompatibility and Alternate Stem Cell Source Working Committee of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(24):4872–4880. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw PJ, Kan F, Woo Ahn K, et al. Outcomes of pediatric bone marrow transplantation for leukemia and myelodysplasia using matched sibling, mismatched related, or matched unrelated donors. Blood. 2010;116(19):4007–4015. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-261958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe N, Matsumoto K, Muramatsu H, et al. Relationship between tacrolimus blood concentrations and clinical outcome during the first 4 weeks after SCT in children. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45(7):1161–1166. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu YM, Jaing TH, Chen YC, et al. Quality of life after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in pediatric survivors: comparison with healthy controls and risk factors. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39(6):502–509. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berbis J, Michel G, Chastagner P, et al. A French cohort of childhood leukemia survivors: impact of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation on health status and quality of life. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(7):1065–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grupp SA, Dvorak CC, Nieder ML, et al. Children’s Oncology Group’s 2013 blueprint for research: stem cell transplantation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(6):1044–1047. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neudorf S, Sanders J, Kobrinsky N, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for children with acute myelocytic leukemia in first remission demonstrates a role for graft versus leukemia in the maintenance of disease-free survival. Blood. 2004;103(10):3655–3661. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atta EH, de Oliveira DC, Bouzas LF, Nucci M, Abdelhay E. Less graft-versus-host disease after rabbit antithymocyte globulin conditioning in unrelated bone marrow transplantation for leukemia and myelodysplasia: comparison with matched related bone marrow transplantation. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuriyama K, Fuji S, Inamoto Y, et al. Impact of low-dose rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin in unrelated hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2016;103(4):453–460. doi: 10.1007/s12185-016-1947-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okamoto YY. Successful bone marrow transplantation for children with aplastic anemia based on a best-available evidence strategy. Pediatr Transplant. 14(8):980–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inamoto Y, Flowers ME, Wang T, et al. Tacrolimus versus cyclosporine after hematopoietic cell transplantation for acquired aplastic anemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(10):1776–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahmoud HK, Elhaddad AM, Fahmy OA, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for non-malignant hematological disorders. J Adv Res. 2015;6(3):449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guardiola P, Socie G, Li X, et al. Acute graft-versus-host disease in patients with Fanconi anemia or acquired aplastic anemia undergoing bone marrow transplantation from HLA-identical sibling donors: risk factors and influence on outcome. Blood. 2004;103(1):73–77. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Locatelli F, Bruno B, Zecca M, et al. Cyclosporin A and short-term methotrexate versus cyclosporin A as graft versus host disease prophylaxis in patients with severe aplastic anemia given allogeneic bone marrow transplantation from an HLA-identical sibling: results of a GITMO/EBMT randomized trial. Blood. 2000;96(5):1690–1697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobson P, Uberti J, Davis W, Ratanatharathorn V. Tacrolimus: a new agent for the prevention of graft-versus-host disease in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;22(3):217–225. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yanik G, Levine JE, Ratanatharathorn V, Dunn R, Ferrara J, Hutchinson RJ. Tacrolimus (FK506) and methotrexate as prophylaxis for acute graft-versus-host disease in pediatric allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26(2):161–167. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park SS, Jun SE, Lim YT. The effectiveness of tacrolimus and minidose methotrexate in the prevention of acute graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children: a single-center study in Korea. Korean J Hematol. 2012;47(2):113–118. doi: 10.5045/kjh.2012.47.2.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.