Abstract

Purpose

The purposes of this study were to evaluate public opinion regarding fertility treatment and gamete cryopreservation for transgender individuals and identify how support varies by demographic characteristics.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional web-based survey study completed by a representative sample of 1111 US residents aged 18–75 years. Logistic regression was used to calculate odd ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of support for/opposition to fertility treatments for transgender people by demographic characteristics, adjusting a priori for age, gender, race, and having a biological child.

Results

Of 1336 people recruited, 1111 (83.2%) agreed to participate, and 986 (88.7%) completed the survey. Most respondents (76.2%) agreed that “Doctors should be able to help transgender people have biological children.” Atheists/agnostics were more likely to be in support (88.5%) than Christian–Protestants (72.4%; OR = 3.10, CI = 1.37–7.02), as were younger respondents, sexual minorities, those divorced/widowed, Democrats, and non-parents. Respondents who did not know a gay person (10.0%; OR = 0.20, CI = 0.09–0.42) or only knew a gay person without children (41.4%; OR = 0.29, CI = 0.17–0.50) were more often opposed than those who knew a gay parent (48.7%). No differences in gender, geography, education, or income were observed. A smaller majority of respondents supported doctors helping transgender minors preserve gametes before transitioning (60.6%) or helping transgender men carry pregnancies (60.1%).

Conclusions

Most respondents who support assisted and third-party reproduction also support such interventions to help transgender people have children.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10815-017-1035-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Transgender, Fertility preservation, Assisted reproduction, Trans health, Transitioning

Introduction

Transgender men and women have a gender identity that is different from their sex assigned at birth. There are approximately 700,000–1,000,000 transmasculine and transfeminine people living in the USA, and several studies have shown that a large proportion (40–50%) of transgender individuals wish to have children [1–8]. Many transgender people “transition” to their identified gender over time, some with the help of hormonal and surgical interventions. There are several questions surrounding biological childbearing in this community, including the optimal time to preserve their reproductive potential prior to or during their transition, if desired [5, 9–11]. For example, a transgender male who has transitioned from female may desire removal of ovaries; if eggs are not cryopreserved before this surgical intervention, the opportunity to have a biological child in the future is no longer possible [12, 13]. While hormonal treatments almost always have reversible effects on spermatogenesis and oocyte maturation, they occasionally can result in permanent loss of fertility, and the psychological effects of reversing hormone therapy are difficult to measure [14, 15]. Given these complexities, it has been recommended that all transgender individuals, regardless of age, be counseled regarding their fertility before initiation of treatment [15].

While many people have come to accept gay and lesbian couples as potential parents, the transgender community has long faced discrimination, including from the medical community [16–21]. As many as one in four transgender adults has reported being denied medical treatment, harassed, or disrespected by a health care provider in a 2010 study by the National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force [22]. People who hold discriminatory beliefs about transgender people may similarly oppose childrearing within this group, and some physicians may be uncomfortable with the idea of caring for this group of patients or feel that they are not adequately trained to do so. Personal biases, both from the lay community and from medical professionals, may create potential barriers to access to care for transgender individuals.

Public opinion, meanwhile, can profoundly impact medical policy [23, 24] and insurance benefits [25], and in the reproductive medicine field, where insurance coverage remains a controversial issue, public support may promote consequential change. Moreover, public opinion affects media coverage, which in turn influences what the public (including the transgender community) may see as viable options for their care. Several previous studies have evaluated public opinion on various reproductive medicine therapies, but none has evaluated public perception of fertility treatments for the transgender community [26–29].

The purposes of this study were therefore to evaluate the public’s opinion of fertility treatment and fertility preservation for the transgender community and to identify characteristics among people who are more or less likely to support fertility preservation in this marginalized group. Our primary hypothesis was that (1) there is public support for fertility preservation for the transgender community. Our secondary hypotheses were that (2) people who support gay and lesbian parenting are more likely to support fertility treatments for transgender patients and 3) support for doctors providing fertility treatment for transgender patients varies by political party and geographic location. By recognizing demographic factors that may act as barriers in access to care, we hope to identify areas where more education is needed and increase the availability of fertility treatment for the transgender community.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition

Data for this cross-sectional web-based survey were collected using SurveyMonkey Audience, a professional online platform with > 30 million volunteer participants, in which investigators can purchase a number of responses with demographic requirements. Individuals who complete SurveyMonkey Audience surveys can receive one of two awards: (1) a donation of $0.50 to a charity of their choice or (2) entry into a sweepstakes to win $100. There is one winner per week. Data sent to investigators from SurveyMonkey is de-identified.

For this study, US residents aged 18–75 years were recruited and screened by SurveyMonkey to obtain a population of respondents representative of recent census data based on distributions of age and gender. Identical surveys were sent to four comparably sized groups: men age 18–44 years, men age 45–75 years, women age 18–44 years, and women age 45–75 years. Respondents were from 49 US states (all but North Dakota), and a precise demographic breakdown of the respondents can be found in the “Results” section. Inclusion in this study required participants to be literate in English and to have access to a computer. This study was found to be exempt by the Partners HealthCare Institutional Review Board.

The survey was distributed in April 2016. Respondents were asked to read a summary page introducing the purpose and content of the survey prior to starting the survey, at which time they could decline to participate. The introduction page included information on infertility treatments such as gamete cryopreservation and gestational surrogacy, as well as definitions of transgender and transitioning. Respondents who agreed to take the survey were then asked a series of 15 multiple-choice questions regarding their opinion of fertility treatment and preservation in the transgender community and an additional 16 demographic questions. Participants were able to type in text if the multiple-choice answers provided did not include their preferred answer. Respondents who opposed in vitro fertilization (IVF), gamete cryopreservation, or use of a gestational carrier under any circumstance were excluded from the final analysis to distinguish those objecting to these assisted reproduction techniques from those opposed to treating the transgender community.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each survey item. Demographic characteristics were compared using logistic regression to calculate unadjusted and adjusted odd ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of support for fertility treatments for transgender people, adjusting a priori for age, gender, race (white, other), and being a biological parent. Representative demographic characteristics evaluated included age, race, gender, parity, geographical location, political party affiliation, religion, income, and knowing someone who has used infertility treatment. For the complete list of evaluated parameters, see the Supplementary Material for the full questionnaire.

Referent groups were considered either as the lowest tail of the distribution for ordinal variables or as the largest group for nominal variables. Respondents who chose “other” as an answer choice were asked to type in a response. Free-text answers were then either manually re-categorized to an existing answer choice (if applicable) or kept as “other” if no existing answer choice sufficed.

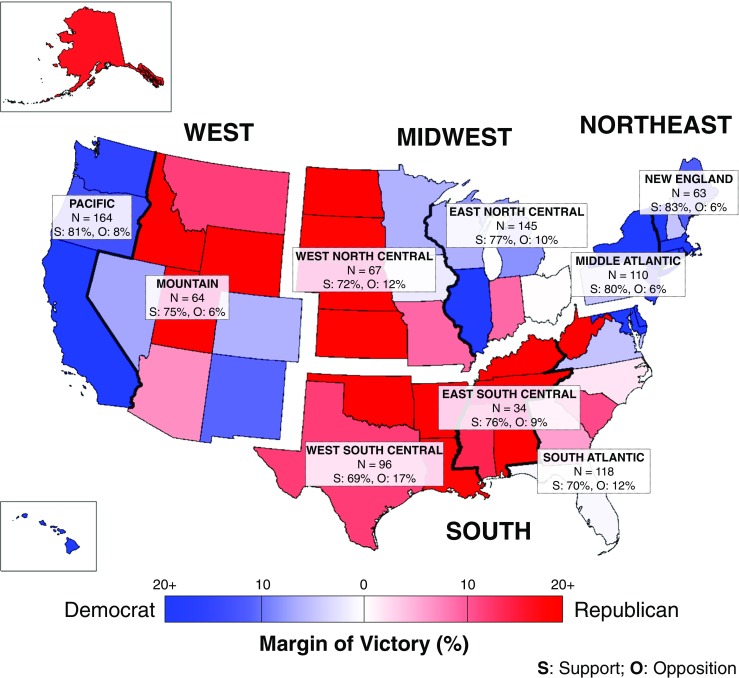

A map was created denoting US census regions and the average margin of victory (i.e., the percentage difference in the popular vote) for each state over the three most recent presidential elections (2008, 2012, and 2016)1 , 2 , 3. States shaded red leaned Republican, and states shaded blue leaned Democrat; deeper shades of each color indicate a larger average margin of victory, with > 20% margin represented as the deepest shades. Support for and opposition to physicians being able to help transgender people have biological children are indicated for each census region.

p values for linear trend were calculated for age and annual household income. SAS 9.3 statistical software (Cary, NC, USA) was used for all analyses, and p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Of 1336 people recruited, 1111 (83.2%) agreed to participate, of which 986 (88.7%) completed the survey. Among these, 3.2, 5.0, and 9.6% were excluded because the respondent opposed IVF, gamete cryopreservation, or use of a gestational carrier under any circumstance, respectively. Demographic characteristics of the remaining 873 participants are shown in Table 1. The largest proportion of respondents were between 45–59 years of age, 56.7% were women, 84.1% considered themselves straight, 49.3% reported being married or in a civil union, and 48.9% had biological children.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of survey respondents; No. (%)

| Demographics | Men n = 368 (42.1) | Women n = 494 (56.6) | Transgender women n = 1 (0.1) | Transgender men n = 5 (0.6) | Other n = 5 (0.6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| 18–29 | 74 (20.3) | 120 (24.3) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (20) | 4 (80) |

| 30–44 | 108 (29.6) | 132 (26.8) | – | 2 (40) | 1 (20) |

| 45–59 | 121 (33.2) | 151 (30.6) | – | 1 (20) | – |

| 60–65 | 62 (17.0) | 90 (18.3) | – | 1 (20) | – |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 289 (78.5) | 419 (84.8) | 1 (100) | 4 (80) | 5 (100) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 18 (4.9) | 22 (4.5) | – | – | – |

| Black | 22 (6.0) | 17 (3.4) | – | – | – |

| Other | 39 (10.6) | 36 (7.3) | – | 1 (20) | – |

| Income (US dollars) | |||||

| ≤ 20,000 | 45 (12.2) | 57 (11.5) | 1 (100) | 2 (40) | 1 (20) |

| 20,001–40,000 | 47 (12.8) | 74 (15.0) | – | – | 3 (60) |

| 40,001–60,000 | 49 (13.3) | 87 (17.6) | – | 1 (20) | – |

| 60,001–80,000 | 56 (15.2) | 82 (16.6) | – | 1 (20) | – |

| 80,001–100,000 | 41 (11.1) | 65 (13.2) | – | – | – |

| 100,001–150,000 | 78 (21.2) | 61 (12.4) | – | 1 (20) | 1 (20) |

| > 150,000 | 52 (14.1) | 68 (13.8) | – | – | – |

| US regions | |||||

| Pacific | 29 (45.3) | 34 (6.9) | – | – | 1 (20) |

| New England | 45 (12.2) | 65 (13.2) | – | – | 1 (20) |

| Middle Atlantic | 61 (16.6) | 84 (17.0) | – | – | 1 (20) |

| East North Central | 36 (9.8) | 29 (5.9) | 1 (100) | – | 1 (20) |

| West North Central | 54 (14.7) | 66 (13.4) | – | 1 (20) | 1 (20) |

| South Atlantic | 10 (2.7) | 24 (4.9) | – | – | – |

| East South Central | 39 (10.6) | 56 (11.3) | – | 1 (20) | – |

| West South Central | 26 (7.1) | 38 (7.7) | – | – | – |

| Mountain | 68 (18.5) | 98 (19.8) | – | 3 (60) | – |

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Gay | 33 (9.0) | 1 (0.2) | – | – | 1 (20) |

| Lesbian | 0 | 21 (4.3) | – | – | – |

| Straight | 317 (86.1) | 416 (84.2) | – | 1 (20) | – |

| Bisexual | 11 (3.0) | 44 (8.9) | 1 (100) | 1 (20) | 2 (40) |

| I don’t know | 6 (1.6) | 4 (0.8) | – | 3 (60) | – |

| Other | 1 (0.3) | 8 (1.6) | – | – | 2 (40) |

| Religion | |||||

| Christian–Protestant | 115 (31.3) | 202 (40.9) | – | – | – |

| Christian–Catholic | 74 (20.1) | 89 (18.0) | – | – | – |

| Jewish | 12 (3.3) | 14 (2.8) | – | – | – |

| Muslim | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.4) | – | – | – |

| Hindu | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.6) | – | – | – |

| Buddhism | 10 (2.7) | 9 (1.8) | – | 1 (20) | – |

| Atheist/agnostic | 129 (35.1) | 143 (29.0) | – | 3 (100) | 4 (80) |

| Other | 21 (5.7) | 32 (6.5) | 1(100) | 1 (20) | 1 (20) |

| Education | |||||

| Grade school | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | – | – | – |

| High school | 25 (6.8) | 34 (6.9) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | – |

| Some college | 66 (17.9) | 90 (18.2) | – | 2 (40) | 1 (20) |

| Technical/associates degree | 38 (10.3) | 69 (14.0) | – | – | – |

| Bachelor’s degree | 136 (37.0) | 185 (37.5) | – | – | 2 (40) |

| Graduate degree | 101 (27.5) | 114 (23.1) | – | 2 (40) | 2 (40) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Never married | 96 (26.1) | 106 (21.5) | 1 (100) | 2 (40) | 1 (20) |

| Married/civil union | 198 (53.8) | 230 (46.6) | – | 1 (20) | 1 (20) |

| Long-term relationship | 42 (11.4) | 84 (17.0) | – | 1 (20) | 3 (60) |

| Separated | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.4) | – | – | – |

| Divorced | 23 (6.3) | 52 (10.5) | – | – | – |

| Widowed | 6 (1.6) | 20 (4.1) | – | 1 (20) | – |

| Know someone with infertility | |||||

| Yes | 188 (51.1) | 308 (62.4) | 1 (100) | 3 (60) | 4 (80) |

| Number of biological children | |||||

| 0 | 190 (51.6) | 248 (50.2) | 1 (100) | 2 (4) | 5 (100) |

| 1 | 55 (15.0) | 77 (15.6) | – | – | – |

| 2 | 74 (20.1) | 105 (21.3) | – | 3 (60) | – |

| ≥ 3 | 49 (13.4) | 64 (12.9) | – | – | – |

| Has adopted/step-children | |||||

| Yes | 52 (14.1) | 98 (19.9) | – | – | – |

| Know someone gay, lesbian, or bisexual | |||||

| Yes, with children | 164 (41.6) | 264 (53.4) | 1 (100) | 4 (80) | 3 (60) |

| Yes, without children | 174 (47.3) | 185 (37.5) | – | – | – |

| No | 41 (11.1) | 45 (9.1) | – | 1 (20) | 2 (40) |

| Know someone transgender | |||||

| Yes, with children | 25 (6.8) | 44 (8.9) | 1 (100) | 4 (80) | 1 (20) |

| Yes, without children | 88 (23.9) | 133 (26.9) | – | – | – |

| No | 255 (69.3) | 317 (64.2) | – | 1 (20) | 4 (80) |

Table 1 demonstrates demographic characteristics of study respondents, excluding those who disagreed with IVF, gamete cryopreservation, or use of a gestational carrier under any circumstance

The proportion of respondents who reported knowing a transgender person was 34.4%, with a distribution across the country ranging from 22.5% in the East South Central and West North Central regions to 35.2%, and 35.8% in the New England and South Atlantic regions, respectively. The majority of respondents agreed with the statement that “Doctors should be able to help transgender people have biological children” (76.2%), and another 14.1% were neutral (Table 2). Of the 9.7% of respondents who opposed, the most common reasons were that “Children could be negatively affected” (63.1%) and “It’s not natural” (46.4%). Atheist or agnostic respondents were significantly more likely to support doctors providing fertility services for transgender people (88.5%) compared to Christian–Protestants (72.4%) (aOR = 3.10, CI = 1.37–7.02), as were younger respondents compared to those aged 45–59 years (85.3 vs. 68.9%), sexual minorities (88.8 vs. 74.0%), those divorced/widowed (84.1 vs. 69.8%), Democrats (86.1 vs. 55.4% and 71.4% for Republicans and Libertarians, respectively), and non-parents of biological children (82.0 vs. 70.0%) in the multivariable-adjusted regression model. Respondents who did not know a gay person (10.0%; aOR = 0.20, CI = 0.09–0.42) or only knew a gay person without children (41.4%; aOR = 0.29, CI = 0.17–0.50) were more often opposed than those who knew a gay parent (48.7%). Similarly, respondents who supported gay parenting of biological children were more likely to support doctors helping transgender people have biological children (651/742; 87.7%) compared with those opposed to gay parenting (4/49; 8.2%). The US census region with the highest number of respondents in support was New England (82.8%); the lowest was West South Central (68.8%), as seen in Fig. 1. Respondents from the Northeast or West were more likely to be in support than those from the South (p = 0.01 and p = 0.03, respectively). Averaging the margin of victory over the last three US presidential elections (2008, 2012, and 2016), the areas associated with most support tended to vote more heavily democratic.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics associated with respondents who “agree” with the statement: “Doctors should be able to help transgender people have biological children”

| Doctors should be able to help transgender people have biological children | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No. (%) disagree 85 (9.7%) |

No. (%) neutral 123 (14.1%) |

No. (%) agreea

665 (76.2%) |

OR (95% CI) unadjusted | OR (95%CI) multivariateb |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 44 (12.0) | 58 (15.8) | 266 (72.3) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Female | 41 (8.3) | 64 (13.0) | 389 (78.7) | 1.57 (1.00–2.47) | 1.55 (0.98–2.46) |

| Transgender male | 0 | 1 (100.0) | |||

| Transgender female | 0 | 5 (100.0) | |||

| Other | 0 | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | ||

| Age group (years) | p = 0.07c | p = 0.40c | |||

| 18–29 | 11 (5.4) | 19 (9.3) | 174 (85.3) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| 30–44 | 25 (10.3) | 32 (13.2) | 186 (76.5) | 0.47 (0.23–0.99) | 0.68 (0.31–1.50) |

| 45–59 | 36 (13.2) | 49 (18.0) | 188 (68.9) | 0.33 (0.16–0.67) | 0.46 (0.22–0.99) |

| ≥ 60 | 13 (8.5) | 23 (18.7) | 117 (76.5) | 0.67 (0.25–1.31) | 0.77 (0.31–1.90) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 62 (8.6) | 89 (12.4) | 567 (79.0) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 9 (10.6) | 13 (32.5) | 18 (45.0) | 0.22 (0.09–0.51) | 0.38 (0.18–0.83) d |

| Black | 4 (4.7) | 6 (15.4) | 29 (74.4) | 0.79 (0.27–2.33) | 0.88 (0.29–2.65) |

| Other | 10 (11.8) | 15 (19.7) | 51 (67.1) | 0.56 (0.27–1.15) | 0.48 (0.23–1.02) |

| Region | |||||

| West | 33 (10.0) | 45 (13.7) | 251 (76.3) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Northeast | 12 (6.9) | 22 (12.6) | 141 (80.6) | 1.54 (0.77–3.09) | 1.24 (0.61–2.53) |

| Midwest | 23 (10.8) | 29 (13.6) | 161 (75.6) | 0.92 (0.52–1.62) | 0.86 (0.48–1.54) |

| South | 17 (10.9) | 27 (17.3) | 112 (71.8) | 0.87 (0.46–1.62) | 0.79 (0.42–1.50) |

| Yearly household income ($US) | P = 0.19c | P = 0.53c | |||

| Religion | |||||

| Christian–non-Catholic | 18 (11.0) | 27 (16.6) | 118 (72.4) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Christian–Catholic | 51 (16.1) | 57 (18.0) | 209 (65.9) | 0.62 (0.35–1.12) | 0.55 (0.30–1.00) |

| Jewish | 1 (3.9) | 4 (15.4) | 21 (80.8) | 3.20 (0.41–25.30) | 2.95 (0.37–23.60) |

| Atheist/Agnostic | 10 (3.6) | 22 (7.9) | 247 (88.5) | 3.77 (1.69–8.42) | 3.10 (1.37–7.02) |

| Other | 5 (5.7) | 13 (14.8) | 70 (79.6) | 2.14 (0.76–6.01) | 2.12 (0.74–6.09) |

| Number of biological children | |||||

| 0 | 29 (6.5) | 51 (11.4) | 366 (82.0) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| 1 or more | 56 (13.1) | 72 (16.9) | 299 (70.0) | 0.42 (0.26–0.68) | 0.48 (0.29–0.80) d |

| Political party | |||||

| Democratic | 12 (3.4) | 37 (10.5) | 304 (86.1) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Republican | 31 (21.0) | 35 (23.7) | 82 (55.4) | 0.10 (0.05–0.21) | 0.09 (0.04–0.20) |

| Libertarian | 4 (11.4) | 6 (17.1) | 25 (71.4) | 0.25 (0.07–0.82) | 0.18 (0.05–0.63) |

| None/other | 38 (11.3) | 45 (13.4) | 254 (75.4) | 0.26 (0.14–0.52) | 0.25 (0.12–0.49) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 51 (11.8) | 79 (18.4) | 300 (69.8) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Single/never married | 20 (9.7) | 19 (9.2) | 167 (81.1) | 1.42 (0.82–2.46) | 0.82 (0.42–1.59) |

| Long-term partner | 9 (6.9) | 13 (10.6) | 108 (83.1) | 2.04 (0.97–4.28) | 1.01 (0.45–2.27) |

| Divorced or widowed | 5 (4.7) | 12 (9.8) | 90 (84.1) | 3.06 (1.19–7.90) | 3.14 (1.19–8.27) |

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Straight | 81 (11.0) | 110 (15.0) | 543 (74.0) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Sexual minoritye | 4 (2.9) | 13 (9.4) | 122 (88.8) | 4.55 (1.64–12.65) | 3.61 (1.27–10.22) |

| Know someone gay, lesbian, or bisexual | |||||

| Yes, with children | 20 (4.7) | 45 (10.6) | 360 (84.7) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Yes, and they do not have children | 50 (13.9) | 55 (15.2) | 256 (70.9) | 0.28 (0.26–0.94) | 0.29 (0.17–0.50) |

| No | 15 (17.2) | 23 (26.4) | 49 (56.3) | 0.18 (0.09–0.38) | 0.20 (0.09–0.42) |

Analyses do not include respondents who were “neutral.” Bolded results indicate those that are statistically significant

aNumbers may not sum to 100

bAdjusted for age, white vs. non-white, gender, having biological children

cTest for linear trend

dAdditionally adjusted for atheist/agnostic religion

eSexual minority refers to respondents who did not identify as straight/heterosexual

Fig. 1.

Percentage of respondents who either support (S) or oppose (O) physicians helping transgender people have biological children according to US census region. This map denotes the US census regions and the political party voted for by each state by average margin of victory over the last three presidential elections (2008, 2012, and 2016). States that leaned Republican are shaded red; states that leaned Democratic are shaded blue. Deeper shades of each color indicate a larger average margin of victory, with > 20% margin represented as the deepest shades. The no. (%) of respondents in each census region who support and oppose physicians being able to help transgender people have biological children are indicated

Respondents were more likely to support doctors helping transgender adults preserve gametes prior to their gender transition (77.1%) compared with transgender minors (60.6%) (Table 3). Female respondents were more likely than male respondents to be in support of doctors helping both adult (81.0 vs. 71.5%; aOR = 1.68, CI = 1.04–2.72) and minor (65.6 vs. 56.0%; aOR = 1.55, CI = 1.10–2.20) transgender people cryopreserve gametes, as were atheist or agnostic respondents compared with Christian–Protestants (adults: 89.6 vs. 71.2%; aOR = 6.11, CI = 2.16–17.31; minors: 73.8 vs. 59.5%; aOR = 2.35, CI = 1.29–4.29). Christian–Catholic respondents were significantly less likely to support gamete cryopreservation for transgender minors (49.2%) compared to Christian–Protestants (59.5%) (aOR = 0.43, CI = 0.27–0.71). Compared with white respondents, Hispanic or Latino respondents were significantly less likely to support gamete cryopreservation at any age, as were Republicans or Libertarians, and parents compared with non-parents. If a respondent did not know a gay person or only knew a gay person who did not have children, they were less likely to be in support than those who knew a gay parent. Approximately half of the respondents who disagreed with gamete preservation for transgender minors (20.3%) chose to write in answers; many of their statements included the sentiment that “Minors are too immature to make this type of life-altering decision.”

Table 3.

Percentage of respondents by demographic characteristics who “agree” with the following statements: (1) “Doctors should be allowed to help transgender adult men and women (≥ 18 years old) freeze eggs or sperm before their transition to the other gender so that they can have a biological child in the future;” (2) “Doctors should be allowed to help transgender minors (< 18 years old) freeze eggs or sperm before their transition to the other gender so that they can have a biological child in the future, if approved by a parent/guardian;” and (3) “Doctors should be able to help a transgender man who has kept his uterus carry a pregnancy in the future”

| Doctors should be allowed to help transgender adults freeze eggs or sperm before their transition | Doctors should be allowed to help transgender minors freeze eggs or sperm before their transition | Doctors should be able to help a transgender man carry a pregnancy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No. (%) agreea

673 (77.1%) |

No. (%) disagree 76 (8.7%) |

No. (%) agreea

529 (60.6%) |

No. (%) disagree 177 (20.3%) |

No. (%) agreea

525 (60.1%) |

No. (%) disagree 139 (15.9%) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 263 (71.5) | 40 (10.9) | 206 (56.0) | 90 (24.5) | 219 (59.5) | 61 (16.6) |

| Female | 400 (81.0) | 36 (7.3) | 314 (63.6) | 87 (17.6) | 296 (59.9) | 77 (15.6) |

| Transgender male | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | |||

| Transgender female | 5 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | |||

| Other | 4 (80.0) | 3 (60.0) | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | ||

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 18–29 | 169 (82.8) | 10 (4.9) | 136 (66.7) | 29 (14.2) | 143 (70.1) | 21 (10.3) |

| 30–44 | 186 (76.5) | 25 (10.3) | 146 (60.1) | 54 (22.2) | 156 (64.2) | 33 (13.6) |

| 45–59 | 196 (71.8) | 32 (11.7) | 152 (55.7) | 64 (23.4) | 147 (53.9) | 59 (21.6) |

| ≥ 60 | 122 (79.7) | 9 (5.9) | 95 (62.1) | 30 (17.0) | 79 (51.6) | 26 (16.7) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 569 (79.3) | 56 (7.8) | 449 (62.5) | 138 (19.2) | 447 (62.3) | 110 (15.3) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 22 (55.0) | 9 (22.5) | 16 (40.0) | 14 (35.0) | 18 (45.0) | 8 (20.0) |

| Black | 31 (79.5) | 3 (7.7) | 24 (61.5) | 10 (25.6) | 23 (59.0) | 4 (10.3) |

| Other | 51 (67.1) | 8 (10.5) | 40 (52.6) | 15 (19.7) | 37 (48.7) | 17 (22.4) |

| Religion | ||||||

| Christian–non-Catholic | 116 (71.2) | 16 (9.8) | 97 (59.5) | 30 (18.4) | 88 (54.0) | 28 (17.2) |

| Christian–Catholic | 218 (68.8) | 48 (15.1) | 156 (49.2) | 101 (31.9) | 149 (47.0) | 78 (24.6) |

| Jewish | 22 (84.6) | 1 (3.9) | 16 (61.5) | 5 (19.2) | 21 (80.8) | 3 (11.5) |

| Atheist/agnostic | 250 (89.6) | 5 (1.8) | 206 (73.8) | 24 (8.6) | 214 (76.7) | 22 (7.9) |

| Other | 67 (76.1) | 6 (6.8) | 54 (61.4) | 17 (19.3) | 53 (60.2) | 8 (9.1) |

| Number of biological children | ||||||

| 0 | 362 (81.2) | 27 (6.1) | 289 (64.8) | 69 (15.5) | 297 (66.6) | 59 (13.2) |

| 1 or more | 311 (72.8) | 49 (11.5) | 240 (56.2) | 108 (25.3) | 228 (53.4) | 80 (18.7) |

| Political party | ||||||

| Democratic | 312 (88.4) | 14 (4.0) | 254 (72.0) | 37 (10.5) | 256 (72.5) | 31 (8.9) |

| Republican | 83 (56.1) | 28 (18.9) | 59 (39.9) | 53 (35.8) | 53 (35.8) | 50 (33.8) |

| Libertarian | 24 (68.6) | 3 (8.9) | 20 (57.1) | 9 (25.7) | 23 (65.7) | 3 (8.6) |

| None/other | 254 (75.4) | 31 (9.2) | 196 (58.2) | 78 (23.2) | 193 (57.3) | 55 (16.3) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 311 (72.3) | 42 (9.8) | 249 (57.9) | 97 (22.6) | 240 (55.8) | 74 (17.2) |

| Single/never married | 163 (79.1) | 19 (9.2) | 129 (62.6) | 38 (18.5) | 135 (65.5) | 37 (18.0) |

| Long-term partner | 109 (83.9) | 9 (6.9) | 84 (64.6) | 24 (18.5) | 92 (70.8) | 13 (10.0) |

| Divorced or widowed | 90 (84.1) | 6 (5.6) | 67 (62.6) | 18 (16.8) | 58 (54.2) | 15 (14.0) |

| Sexual orientation | ||||||

| Straight | 549 (62.9) | 73 (10.0) | 425 (57.9) | 163 (22.2) | 415 (56.5) | 126 (17.2) |

| Sexual minorityb | 124 (89.2) | 3 (2.2) | 104 (74.8) | 14 (10.1) | 110 (79.1) | 13 (9.4) |

| Know someone gay, lesbian, or bisexual | ||||||

| Yes, with children | 363 (85.4) | 18 (4.2) | 295 (69.4) | 60 (14.1) | 291 (68.5) | 41 (9.7) |

| Yes, without children | 257 (71.2) | 43 (11.9) | 194 (53.7) | 94 (26.0) | 195 (54.0) | 75 (20.8) |

| No | 53 (60.9) | 15 (17.2) | 40 (46.0) | 23 (26.4) | 39 (44.8) | 23 (26.4) |

Does not include respondents who were “neutral”

aNumbers may not sum to 100

bSexual minority refers to respondents who did not identify as straight/heterosexual

Of all the questions posed on the survey, respondents were least likely to support doctors helping a transgender man who kept his uterus carry a pregnancy (60.1%); an additional 23.9% were neutral (Table 3). There was a significant inverse trend toward decreasing support with increasing age (test for linear trend, p = 0.01). The most common reason for opposition was that “The children could be negatively affected” (57.6%). As with the questions above, similar demographic associations were seen, with Democrats, sexual minorities, and atheist or agnostic respondents most likely to be in support. There were no significant differences in household income, perceived importance of having a biological child, or education level for these survey items in the multivariate analysis.

Overall, 41.2% of respondents agreed that insurance companies should cover the medical costs of transitioning, while 55.4% agreed that insurance should cover the costs of gamete cryopreservation prior to a transition. Approximately one third and one quarter of respondents disagreed with insurance companies covering the costs of transitioning and gamete cryopreservation, respectively. There was a minimal difference in the percentage of respondents who agreed with allowing transgender people to have children based on gender of their partners (72.1 and 71.5% for partners of the opposite and same genders, respectively).

Discussion

The media’s portrayal of transgender people has increased, prompting many to form their own opinions about the transgender community. Life for a transgender person can be challenging, with the general lay public having distinct viewpoints on access to health care and childrearing for transgender individuals [7]. This has been particularly highlighted by recent reports of transgender men who have kept their uteri and carried a pregnancy, bringing this topic to the forefront of public debate [5, 30].

The present study, to our knowledge, is the first to evaluate public opinion of fertility treatment and preservation for the transgender community. This study confirmed our primary hypothesis that there is general support for doctors helping transgender individuals have biological children and for providing fertility treatment for the transgender community. In fact, over 90% of all respondents either agreed with or were neutral to doctors providing fertility care to transgender individuals, and overall differences between subgroups were small. This is encouraging, as it is recommended that prior to initiation of hormonal or surgical treatment for transitioning, there should be a discussion of the impact on fertility [15]. As the number of transgender people who opt to transition medically and/or surgically increases, and as they learn about childrearing options, it is likely that access to fertility treatment and preservation will improve for this group [31–33].

We were surprised at the relatively high percentage of respondents who reported knowing a transgender person (> 1/3). At least 20% of respondents from each US census region reported knowing a transgender person, with the highest proportions of respondents living on the country’s coasts (New England, Mid Atlantic, South Atlantic, and Pacific). Respondents who knew a gay parent were more likely to support fertility treatment and preservation for the transgender community than respondents who only knew gay non-parents. This was true for all major questions asked and may be due to positive interactions with sexual minorities or familiarity with parenting in the LGBTQ+ community as a whole. In support of our secondary hypothesis, respondents who supported gay parenting of biological children were ten times more likely to support doctors helping transgender people have biological children than those opposed to gay parenting (87.7 vs. 8.2%, respectively). We believe that this may be due to increased acceptance toward others’ lifestyles.

Interestingly, even after adjusting for age in the multivariate analysis, respondents who were biological parents were less likely to support fertility treatment and preservation for transgender people than non-parents. Similarly, respondents who were Hispanic or Latino were less likely to be in support. This may be due to the fact that both biological parents (23%) and adoptive parents (19%), as well as Hispanic/Latino respondents (18%), were less likely to be atheist/agnostic than non-parents (29%) or non-Hispanic whites (34%), which was consistently related to higher levels of support; however, while adjusting for religion attenuated these effects, being a parent or being Hispanic/Latino remained significantly associated with less support. Thus, religious affiliation is not the only driver of these relationships.

There was less support for fertility treatment for transgender minors than for adults. Participants who supported treatment for transgender adults but not minors expressed concern about the maturity of minors in making what could be permanent decisions regarding their fertility. In most cases, gamete preservation would maintain this choice to later in life, so the respondents may have been showing their lack of support for early transition, not early fertility care per se. Many respondents reported that they would support doctors providing fertility care for transgender individuals once they reached the age of 18. Only 60% of respondents supported doctors helping transgender men who have kept their uteri carry a pregnancy. Common write-in comments included that “People could not both be a transgender man and carry a pregnancy [sic] at the same time.” This is likely due to lack of knowledge about the definition of transgender, which does not require any medical or surgical intervention to achieve, but is rather a sense of one’s own gender identity, including that such an identity may not conform to a traditional binary paradigm. Interestingly, a higher number of respondents agreed that insurance companies should cover the cost of gamete cryopreservation prior to a transition (55.4%) than should cover the costs of transitioning itself (41.2%). This may be due to increased knowledge about oocyte or sperm cryopreservation for indications other than fertility preservation in the transgender population among the general public.

As shown in Fig. 1, the US census regions with the highest percentage of respondents in support of doctors helping transgender people have children were New England and Pacific. These regions comprised the states that are most heavily Democratic, which was similarly associated with higher levels of support, and may be responsible for these findings [34, 35]. In contrast, respondents from the West South Central region were least likely to be in support; correspondingly, residents of these states are more likely to be Republican. These findings are in support of our secondary hypothesis.

It has been estimated that approximately 0.3% of the US population is transgender [1, 2, 7]; interestingly, the proportion of individuals who reported being transgender (0.7%) or “other gender” (0.6%) was higher among study respondents. This may be due to the screening process prior to survey initiation in which participants could decline completing the questionnaire, as well as our exclusion criteria. It is possible that given the sensitive topic and personal relevance, a higher percentage of transgender people opted to complete the survey.

This study has several limitations. As with all national surveys, there is the possibility of survey selection bias and issues of generalizability. After reading an introductory paragraph, respondents had the choice to complete the survey or not, and demographic characteristics of respondents who chose to participate may be inherently different than those who declined. Of note, individuals who declined to take the survey were more likely to be male (54.2%) and > 44 years old (57.3%). To decrease bias, the survey was distributed to potential respondents according to US census distribution by age and gender. Furthermore, respondents may not necessarily have provided accurate information in this survey, a limitation of all surveys. This survey was given electronically to English-speaking US residents and may be biased toward the computer literate. Respondent anonymity should have encouraged candid responses, as the investigators were entirely blinded to the respondents’ personal identifying information. A major strength of this study was its large number of participants. Furthermore, this study helps to fill a void in the literature, in which there is a paucity of information regarding transgender health.

Public perception has an important influence on medical insurance policy and coverage. This large public opinion survey confirms that a majority of US residents who support assisted reproductive technologies similarly support transgender people having biological children. Most respondents endorse physicians providing medical care to help the transgender community achieve this goal via fertility treatment and gamete cryopreservation, and the knowledge that this is generally supported is meaningful. There are many demographic characteristics associated with more or less support, and we hope that by identifying factors that may act as barriers against access to treatment, we can provide education to those who have misconceptions about transgender people and transitioning and reach more members of the transgender community to provide necessary fertility care.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 27 kb)

Acknowledgements

Funding information

This study was funded by an intramural grant from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. This funding provided monetary support for data collection.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

E.G. receives royalties from UpToDate, Springer, and BioMed Central and receives research funding from Serono unrelated to this work. R.A. is a consultant for the New England Cryogenic Center. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

The findings from this study were presented as a poster at the 72nd American Society for Reproductive Medicine annual meeting in Salt Lake City, UT from October 15 to 19, 2016.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10815-017-1035-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Conron KJ, Scott G, Stowell GS, Landers SJ. Transgender health in Massachusetts: results from a household probability sample of adults. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):118–122. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collin L, Reisner SL, Tangpricha V, Goodman M. Prevalence of transgender depends on the “case” definition: a systematic review. J Sex Med. 2016;13(4):613–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wierckx K, Van Caenegem E, Pennings G, Elaut E, Dedecker D, Van de Peer F, et al. Reproductive wish in transsexual men. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(2):483–487. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Sutter P, Kira K, Verschoor A, Hotimsky A. The desire to have children and the preservation of fertility in transsexual women: a survey. Int J Transgenderism. 2002;6(3):215–221. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obedin-Maliver J, Makadon HJ. Transgender men and pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2016;9(1):4–8. doi: 10.1177/1753495X15612658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gates GJ. How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender? Available at: http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-How-Many-People-LGBT-Apr-2011.pdf. (2011). Accessed 12 Mar 2017.

- 7.Stroumsa D. The state of transgender health care: policy, law, and medical frameworks. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):e31–e38. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tornello SL, Bos H. Parenting intentions among transgender individuals. LGBT Health. 2017;4(2):115–120. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Sutter P. Gender reassignment and assisted reproduction: present and future reproductive options for transsexual people. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(4):612–614. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.4.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.T’Sjoen G, Van Caenegem E, Wierckx K. Transgenderism and reproduction. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20(6):575–579. doi: 10.1097/01.med.0000436184.42554.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace SA, Blough KL, Kondapalli LA. Fertility preservation in the transgender patient: expanding oncofertility care beyond cancer. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014;30(12):868–871. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2014.920005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy TF. The ethics of fertility preservation in transgender body modifications. J Bioeth Inq. 2012;9(3):311–316. doi: 10.1007/s11673-012-9378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shires DA, Jaffee K. Factors associated with health care discrimination experiences among a national sample of female-to-male transgender individuals. Health Soc Work. 2015;40(2):134–141. doi: 10.1093/hsw/hlv025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Roo C, Tilleman K, T’Sjoen G, De Sutter P. Fertility options in transgender people. Int Rev psychiatry. 2016;28(1):112–119. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1084275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis P, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, Gooren LJ, Meyer WJ, Spack NP, et al. Endocrine treatment of transsexual persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(9):3132–3154. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James-Abra S, Tarasoff LA, Green D, Epstein R, Anderson S, Marvel S, et al. Trans people’s experiences with assisted reproduction services: a qualitative study. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(6):1365–1374. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaffee KD, Shires DA, Stroumsa D. Discrimination and delayed health care among transgender women and men: implications for improving medical education and health care delivery. Med Care. 2016;54(11):1010–1016. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unger CA. Care of the transgender patient: the role of the gynecologist. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(1):16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scout Transgender health and well-being: gains and opportunities in policy and law. Am J Orthop. 2016;86(4):378–383. doi: 10.1037/ort0000192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White Hughto JM, Murchison GR, Clark K, Pachankis JE, Reisner SL. Geographic and individual differences in healthcare access for U.S. transgender adults: a multilevel analysis. LGBT Health. 2016;3(6):424–433. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landers S, Kapadia F. The health of the transgender community: out, proud, and coming into their own. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(2):205–206. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, With DM, Herman JL, Harrison J, et al. National transgender discrimination survey report on health and healthcare: findings of a study by the national center for transgender equality and national gay and lesbian task force. 2010. Available at: http://www.thetaskforce.org/static_html/downloads/resources_and_tools/ntds_report_on_health.pdf. Accessed 12 Mar 2017.

- 23.Burstein P. The impact of public opinion on public policy: a review and an agenda. Polit Res Q. 2003;56(1):29–40. doi: 10.1177/106591290305600103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blendon RJ, Benson JM. Americans’ views on health policy: a fifty-year historical perspective. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20(2):33–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.2.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pacheco J, Maltby E. The role of public opinion—does it influence the diffusion of ACA decisions? J Health Polit Policy Law. 2017;42(2):309–340. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3766737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee MS, Farland LV, Missmer SA, Ginsburg ES. Limitations on the compensation of gamete donors: a public opinion survey. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(6):1355–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mok-Lin E, Missmer S, Berry K, Lehmann LS, Ginsburg ES. Public perceptions of providing IVF services to cancer and HIV patients. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(3):722–727. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis EI, Missmer SA, Farland LV, Ginsburg ES. Public support in the United States for elective oocyte cryopreservation. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(5):1183–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adashi EY, Cohen J, Hamberger L, Jones HW, de Kretser DM, Lunenfeld B, et al. Public perception on infertility and its treatment: an international survey. The Bertarelli Foundation Scientific Board. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(2):330–334. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Light AD, Obedin-Maliver J, Sevelius JM, Kerns JL. Transgender men who experienced pregnancy after female-to-male gender transitioning. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(6):1120–1127. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dekker MJHJ, Wierckx K, Van Caenegem E, Klaver M, Kreukels BP, Elaut E, et al. A European network for the investigation of gender incongruence: endocrine part. J Sex Med Elsevier. 2016;13(6):994–999. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.03.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fugate SR, Apodaca CC, Hibbert ML. Gender reassignment surgery and the gynecological patient. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 2001;8(1):22–24. doi: 10.1016/S1068-607X(00)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dhejne C, Öberg K, Arver S, Landén M. An analysis of all applications for sex reassignment surgery in Sweden, 1960-2010: prevalence, incidence, and regrets. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(8):1535–1545. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S. Census Bureau. Statistical abstract of the United States. 2012. Available at: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2011/compendia/statab/131ed/elections.html. Accessed 12 Mar 2017.

- 35.Saad L. Heavily Democratic states are concentrated in the East. 2012. Available from: http://www.gallup.com/poll/156437/heavily-democratic-states-concentrated-east.aspx. Accessed 12 Mar 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 27 kb)