Abstract

Glucosinolates (GSLs) and their hydrolysis products present in Brassicales play important roles in plants against herbivores and pathogens as well as in the protection of human health. To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the formation of species-specific GSLs and their hydrolysed products in Raphanus sativus L., we performed a comparative genomics analysis between R. sativus and Arabidopsis thaliana. In total, 144 GSL metabolism genes were identified, and most of these GSL genes have expanded through whole-genome and tandem duplication in R. sativus. Crucially, the differential expression of FMOGS-OX2 in the root and silique correlates with the differential distribution of major aliphatic GSL components in these organs. Moreover, MYB118 expression specifically in the silique suggests that aliphatic GSL accumulation occurs predominantly in seeds. Furthermore, the absence of the expression of a putative non-functional epithiospecifier (ESP) gene in any tissue and the nitrile-specifier (NSP) gene in roots facilitates the accumulation of distinctive beneficial isothiocyanates in R. sativus. Elucidating the evolution of the GSL metabolic pathway in R. sativus is important for fully understanding GSL metabolic engineering and the precise genetic improvement of GSL components and their catabolites in R. sativus and other Brassicaceae crops.

Introduction

Glucosinolates (GSLs), a large class of sulfur-rich secondary metabolites whose hydrolysis products display diverse bioactivities, function both in defence and as an attractant in plants, play a role in cancer prevention in humans and act as flavour compounds1–4. GSLs are present in the pungent plants of the order Brassicales, which consists of sixteen families5, including Brassicaceae, Capparidaceae, Caricaceae and Euphorbiaceae (specifically the genus Drypetes)6. There is great variation in GSL components and contents from species to species, with more than 200 types of GSLs identified5,7. These diverse GSLs have been classified into three major groups based on the structures of their various amino acid precursors: the aliphatic GSLs, derived from methionine, isoleucine, leucine or valine; the aromatic GSLs, derived from phenylalanine or tyrosine; and the indole GSLs, derived from tryptophan2,8. The basic biosynthesis pathway of aliphatic and aromatic GSLs comprises three phases: side-chain elongation, core structure formation and secondary modifications9.

The glucosinolate–myrosinase system involved in Brassicales secondary metabolism has been well studied. GSLs and myrosinase (thioglucoside glucohydrolase, EC 3.2.1.1471) are normally separated into the partitioned spaces of cells. GSLs can be enzymatically hydrolysed into several different types of breakdown products, such as isothiocyanates (ITCs), epithionitriles, and nitriles, which differ among species10, depending on the enzyme, substrate, pH, and presence of iron ions, while GSLs and myrosinase are encountered when tissues have been disrupted11. ITC, a pungent compound specific to Brassicaceae plants, is well known to exert antimicrobial activity against bacteria and fungi in plants12,13 and to effectively decrease the carcinogenic risk of colon and lung cancer14,15. In contrast, epithionitriles and nitriles have been shown to have little potential for conferring health-benefits16,17.

Radish (Raphanus sativus L., 2n = 2x = 18), a member of the Brassiceae tribe in the plant family Brassicaceae14, is a historically cultivated crop worldwide. R. sativus is a relative of B. rapa and B. oleracea. The main GSLs in the seeds of B. rapa and B. oleracea are progoitrin and gluconapin18,19, both of which are aliphatic; however, in the roots of B. rapa and B. oleracea, the predominant GSL is gluconasturtiin, which is aromatic19. Glucoraphenin, which accounts for 70–95% of the total GSLs in seeds of R. sativus, and glucoraphasatin, which can account for 50–90% of the total GSLs in roots, are aliphatic GSLs specific to R. sativus 20–22. Aliphatic GSLs are predominant in the seeds of R. sativus, which has also been demonstrated in B. rapa and B. oleracea 18,19. In B. rapa and B. oleracea, the major GSL hydrolysis products are nitriles and epithionitriles rather than ITCs23,24. In contrast, ITCs are preferentially produced in R. sativus, whereas a small amount of nitriles and epithionitriles are formed25.

In the model plant A. thaliana, many genes have been investigated in the context of controlling GSL biosynthesis2,26. Furthermore, in comparative studies with A. thaliana, the genes that control GSL biosynthesis in Brassicaceae vegetables have been identified and characterized. One hundred two and 105 GSL biosynthesis genes were identified in B. rapa 27 and B. oleracea 28, respectively. Moreover, 87 and 104 GSL biosynthesis genes were reported in two R. sativus genomes29,30, respectively. The greatest variation between the GSL profiles of B. rapa, B. oleracea and R. sativus is mainly attributed to the duplication or loss of two genes, GRS1 and AOP 28,29,31. GRS1 catalyses the dehydrogenation reaction to generate the unsaturated 4-carbon GSL from glucoerucin or glucoraphanin to obtain glucoraphasatin or glucoraphenin, respectively; these reactions are specific to R. sativus 31. AOP2 and AOP3 catalyse the formation of alkenyl and hydroxyalkyl GSLs, respectively28. Only one AOP2 is functional in B. oleracea, and no AOP2 homologue has been identified in R. sativus; however, three copies of AOP2 have been identified in B. rapa, and no AOP3 homologue has been identified in these three vegetables. Therefore, low amounts of sinigrin and gluconapin were found in R. sativus 27–29. Epithiospecifier protein (ESP) and nitrile-specifier protein (NSP) can catalyse GSL to produce nitriles and epithionitriles, respectively32,33, but the enzyme cofactor ESP is inactivated in R. sativus 34. Although several studies on R. sativus genes have involved GSL biosynthetic and degradation pathways29–31, the mechanism responsible for the existence and distribution of both species-specific GSLs and the hydrolysis products of these GSLs remains unclear, which leads to the questions of why R. sativus seeds show substantial accumulation of aliphatic GSLs rather than aromatic and indole GSLs and why low amounts of nitriles exist in R. sativus. Furthermore, the tissue-specific distribution of the two dominating GSLs (glucoraphenin and glucoraphasatin) remains to be elucidated in R. sativus.

In this study, we systematically identified GSL metabolism genes in R. sativus. Furthermore, we present several interesting observations that may explain the formation and distribution of species-specific GSLs and their hydrolysed products in R. sativus. The results of this study contribute to a more thorough understanding of how to precisely genetically modify and improvement of the the GSL metabolism pathway in R. sativus and its relatives.

Results

Identification and analysis of GSL genes in R. sativus

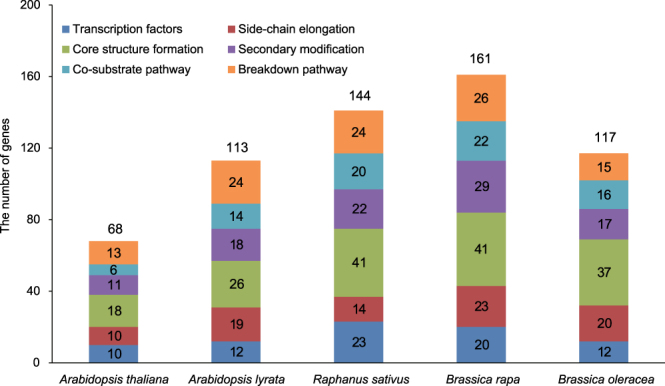

By comparing the draft R. sativus genome35 with the A. thaliana genome, we discovered 144 GSL genes, which were slightly fewer than the 161 GSL genes present in B. rapa, greater than the 113 GSL genes of Arabidopsis lyrata and the 117 GSL genes of B. oleracea, and two-fold higher than the 68 found in A. thaliana (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Notably, R. sativus homologues corresponding to 17A. thaliana GSL genes were not identified in this study. These A. thaliana genes include MAM3, IPMI-SSU3, IPMDH3, CYP79F2, three FMOGS-OX genes and two transcription factors (Supplementary Table S1). In addition, TGG2 was not found in the ‘XYB36-2’ genome, but two TGG2 genes were reported by Jeong et al.30. Regarding gene numbers, there was less variation, with 40% more side-chain elongation genes observed in R. sativus compared to A. thaliana, whereas in the co-substrate pathway, the number of genes found in R. sativus was 2.33 times the number present in A. thaliana (Fig. 1). As aliphatic GSLs are the major GSLs present in R. sativus, the loss, retention and expansion of the GSL genes may have led to the accumulation of species-specific GSLs in R. sativus (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Numbers of GSL genes in R. sativus and related species. The numbers in the colour blocks represent the gene numbers in the corresponding sub-pathway categories. The numbers above the columns represent the total gene numbers in the corresponding species.

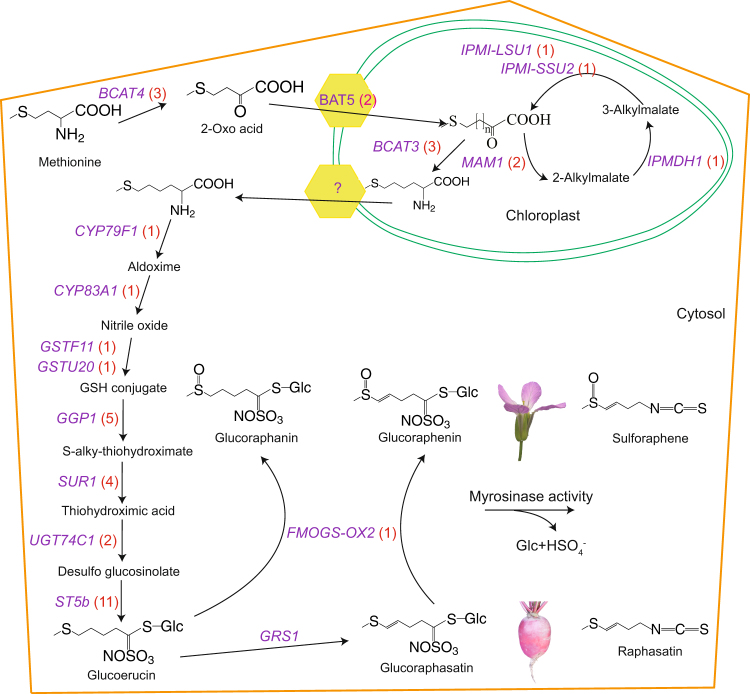

Figure 2.

Putative aliphatic GSL biosynthetic and degradation pathways in R. sativus. Glucoraphasatin is principally found in the root of R. sativus, whereas glucoraphenin is detected mainly in the flowers. The genes shown in purple represent the genes involved in aliphatic GSL biosynthesis in R. sativus, and the numbers in the red brackets are the numbers of corresponding genes in R. sativus. The yellow polygon stands for the translocator on the chloroplast membrane. The symbol ‘?’ represents unknown genes.

Expansion of the GSL metabolic genes in R. sativus

Gene copy numbers can be expanded in four major ways: genome duplication, segmental duplication, tandem duplication and via transposable elements36. Most of the retained genes (36 out of 51) were present as multi-copies in R. sativus (Supplementary Table S1), which may have resulted from tandem duplication or whole-genome triplication (WGT) occurring after the divergence of R. sativus and A. thaliana. Of the 36 expanded genes, 25 AtGSL genes have syntenic relationships to 51 RsGSL genes (Supplementary Table S2). Furthermore, 16 of the 36 over-retained AtGSL genes were tandemly duplicated and distributed in 17 tandem arrays in R. sativus (Supplementary Table S3). These data showed that tandem duplication and WGT substantially contributed to the expansion of GSL metabolic genes in R. sativus.

We analysed the number and the ratio of single-copy to multi-copy homologous genes to reveal the retention status of the three types of GSL core structure formation genes in R. sativus after the WGT. The gene copy number ratios between R. sativus and A. thaliana were 2 (6:3), 0.8 (5:4) and 1 (4:4) for aliphatic, indole and aromatic GSL core structure formation genes, respectively (Table 1). Furthermore, the downstream genes (GGP1, SUR1, UGT74C1 and ST5b), which retained more than one copy, were more frequently duplicated than upstream genes in the pathway for aliphatic GSL core structure biosynthesis in R. sativus (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Number and ratio of single-copy to multi-copy homologues of GSL core structure formation genes in R. sativus.

| Types of GSLs | Number of homologues with different copies | Ratio of single to multiple copies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | Total | ||

| aliphatic GSLs | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 3:6 |

| indole GSLs | 0 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 5:4 |

| aromatic GSLs | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 4:4 |

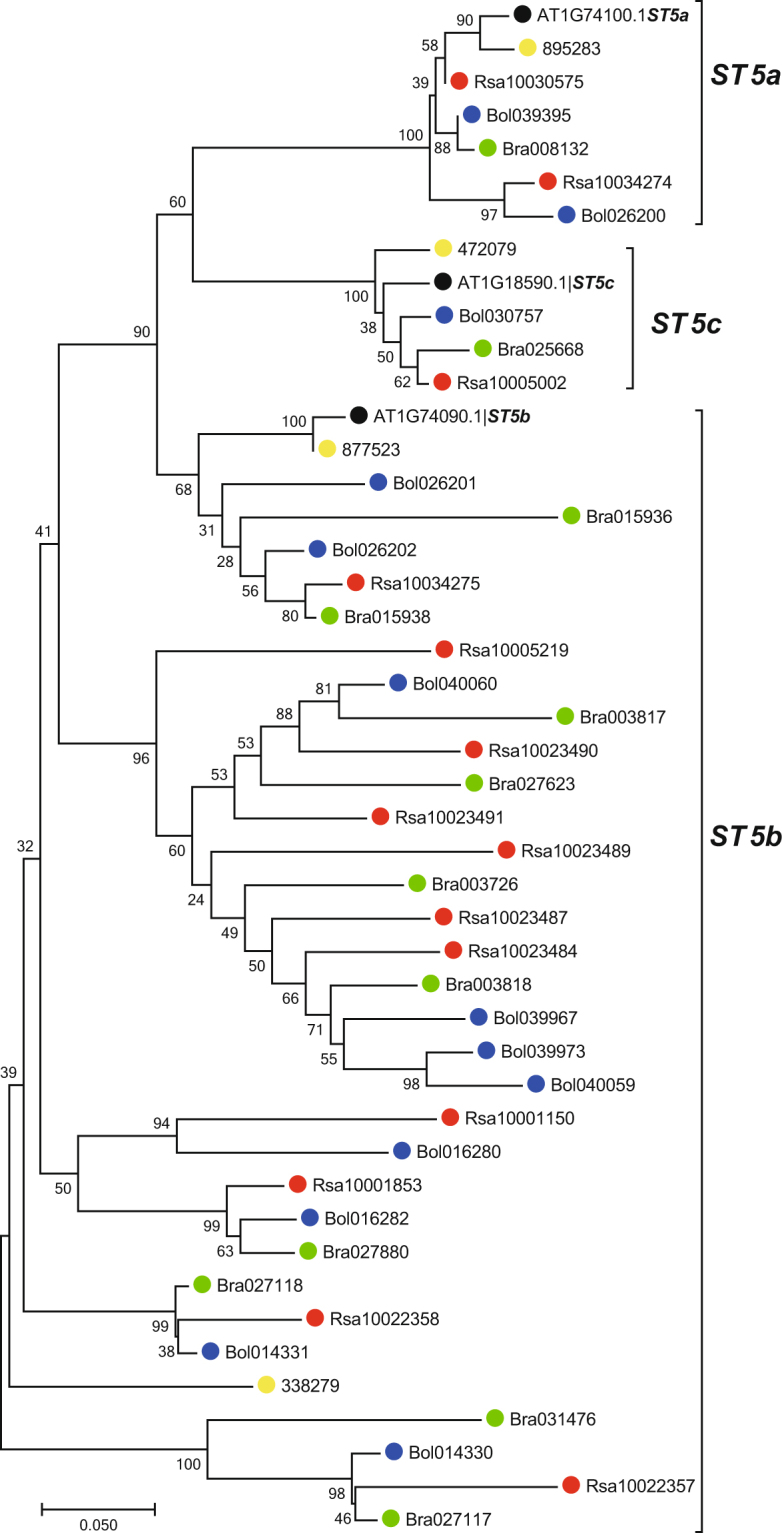

Notably, the ST genes were found to be highly expanded in R. sativus, and most of the ST copies (8 out of 14) in R. sativus were tandemly duplicated. R. sativus contained 11 copies of the ST5b gene, which encodes desulfoglucosinolate sulfotransferase, which is involved in the final step of GSL core structure biosynthesis37. The phylogenetic tree of the ST genes in R. sativus and its closely related species revealed that ST5a and ST5b, especially the latter, have undergone the greatest amount of expansion in R. sativus, B. rapa and B. oleracea. The copies of ST5b were clustered into three groups, two of which included only ST5b copies from R. sativus, B. rapa and B. oleracea, implying that they were inherited from a common ancestor and diverged via tandem duplication (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree of the ST genes in R. sativus and four related species. The full-length amino acid sequences were aligned with ClustalW, and the NJ tree was constructed with MEGA using 1000 bootstrap replicates. Each ST gene is indicated along the lines on the right. R. sativus proteins are marked with solid red dots. The solid black, yellow, green and blue dots represent A. thaliana, A. lyrata, B. rapa and B. oleracea, respectively.

Expression patterns of FMOGS-OX and MYB118 genes in R. sativus

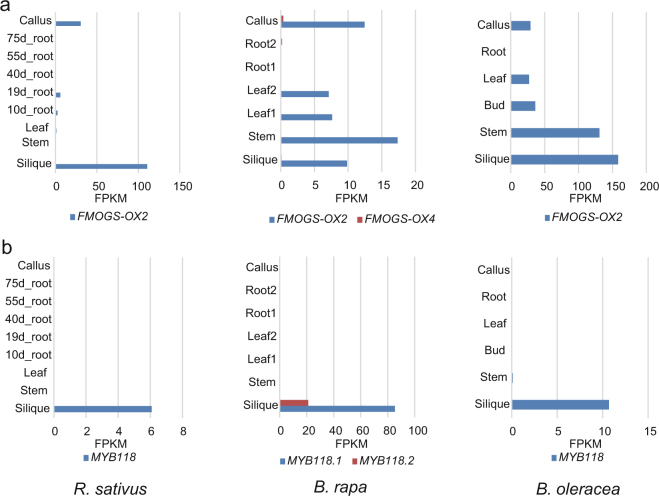

FMOGS-OX1-4 S-oxygenates both short- and long-chain methylthioalkyl GSLs to produce the corresponding methylsulfinylalkyl GSL38. Only FMOGS-OX2 was identified as a single copy gene in R. sativus. Transcriptome analysis indicated that FMOGS-OX2 is highly expressed in the silique but minimally expressed in the other tissues of R. sativus. FMOGS-OX2 was also retained as one copy in B. rapa and B. oleracea and is expressed in all tissues except the roots. In addition, one FMOGS-OX4 gene was identified in B. rapa, but this gene was minimally expressed in all tissues (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

Expression levels of FMOGS-OX2 and MYB118. (a) Expression levels of FMOGS-OX genes in various tissues of R. sativus, B. rapa and B. oleracea. (b) Expression levels of MYB118 in various tissues of R. sativus, B. rapa and B. oleracea. The coloured scale bar represents the FPKM values.

MYB115 and MYB118 play key roles in the aliphatic GSL biosynthetic pathway, acting as negative regulators in the benzoyloxy GSL pathway39. We have found that MYB115 is lost but that MYB118 is present in 1, 2 and 1 copies in R. sativus, B. rapa and B. oleracea, respectively. Interestingly, MYB118 was expressed only in the silique in B. rapa and R. sativus and was expressed highly in the silique but at low levels in other tissues in B. oleracea (Fig. 4b).

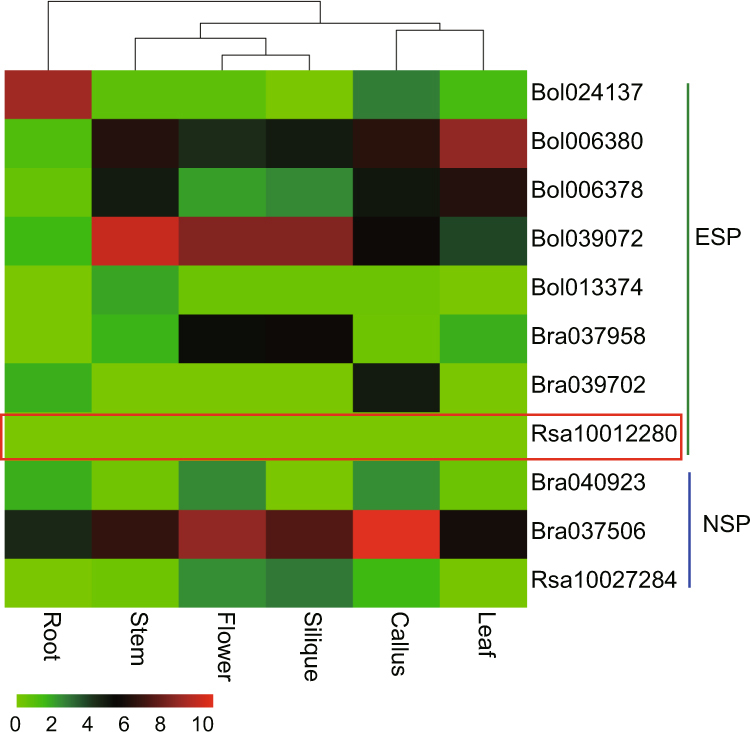

Putative non-functional ESP and tissue-specific expression of NSP genes in R. sativus

When tissues of Brassicales plants are damaged, myrosinase is released, and glucosinolates are degraded to isothiocyanate, thiocyanate, or nitrile derivatives. Although two R. sativus myrosinase genes have been cloned by Hara et al.40 and a total of 11R. sativus myrosinase genes were identified by Mitsui et al.29, it remains unclear why non-nitrile products exist in R. sativus. We found one ESP gene in R. sativus; we also identified two copies of ESP in B. rapa and five copies in B. oleracea. The RNA-seq data indicated that the ESP genes were not expressed in R. sativus but were expressed in both B. rapa and B. oleracea (Fig. 5). NSP, whose product promotes the breakdown of glucosinolates into nitrile derivatives, was found to be retained as one copy in R. sativus and as two copies in B. rapa. Interestingly, in R. sativus, the NSP5 gene was expressed at a minimal level in the flowers, seedpods and callus and was not expressed in the roots, but one of the copies in B. rapa was highly expressed (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Expression of the ESP and NSP genes in R. sativus, B. oleracea, B. rapa and A. thaliana. Expression analysis of the ESP and NSP genes in: root, stem, flower, silique, callus and leaf tissues. The coloured scale bar in the upper right corner of the figure represents the log2 of FPKM values.

Discussion

We identified the counterparts of most of the A. thaliana GSL metabolic genes, which are present in various copy numbers in R. sativus. Compared with the GSL genes identified in two previously reported genomes, the copy numbers were the same for most of the identified genes29,30, with the exception of TGG2. The two R. sativus TGG2 genes reported by Jeong et al.30 are not considered to be homologues, since these two genes were identified by using homologue searches based on the sequence of AT4G11150, which does not encode the TGG2 gene in A. thaliana. The corresponding homologue of TGG2 (Rs303830) identified by Jeong et al.30 were identified in the ‘XYB36-2’ and ‘Aokubi’ genomes, but they represented the homologues of TGG1 in these two genomes29.

The qualitative and quantitative changes in the GSL profiles of R. sativus may be due to the loss, expansion, non/neo-functionality and tissue/stage-specific expression of GSL genes. According to our comprehensive and comparative analysis based on genome and transcriptome data from this study and previous research, these changes corresponded to the evolution of the R. sativus genome29–31,35. In terms of side-chain elongation, the absence of MAM3 led to a lack of long-chain aliphatic GSLs in R. sativus, and this result is consistent with Mitsui et al.29. We also found that the loss of CYP79F2, of which the knockout decreases the abundance of long-chain aliphatic GSLs in A. thaliana, may also result in short-side-chain aliphatic GSLs in R. sativus 41,42. Considering that functional MAM3 genes were found in B. rapa and B. oleracea, the loss of CYP79F2 might be the main reason for the predominance of short-side-chain aliphatic GSLs observed in these two species. In addition, no homologues of IPMI-SSU3 or IPMDH3 from A. thaliana were found in R. sativus. The IPMIs, which are composed of a large subunit and a small subunit, catalyse the isomerization reaction. IPMI-SSU3 encodes the small subunit. However, knockout mutants of IPMI-SSU3 result in small changes in GSL levels in A. thaliana 43. IPMDH3 is a predicted enzyme that has a similar function to IPMDH144, which promotes glucosinolate accumulation45,46. Therefore, the loss of IPMI-SSU3 and IPMDH3 is likely to be offset by IPMI-LSU1, IPMI-LSU2 and IPMDH1.

Moreover, duplicated genes may enhance the potential for the quantitative variation of a particular trait47. Interestingly, most of the GSL genes were present in multiple copies. Syntenic analysis demonstrated that GSL genes have increased their copy numbers through WGT. In addition to WGT, some genes also expanded in number through tandem duplication, such as ST5b, which is present in 11 copies in R. sativus. Notably, expansion was observed for more aliphatic GSL core structure formation genes than for indole and aromatic GSL genes. Further, the biosynthesis genes for the core structures of aliphatic GSLs that were present in downstream locations were more over-retained than those in upstream locations. The redundancy of the downstream genes may guarantee products for successful synthesis of aliphatic GSLs.

Furthermore, with respect to the secondary modification step, three FMOGS-OX genes (FMOGS-OX1, FMOGS-OX3 and FMOGS-OX4) and two AOP genes (AOP2 and AOP3) were lost. FMOGS-OX1-4 S-oxygenates both short- and long-chained methylthioalkyl GSLs to produce the corresponding methylsulfinylalkyl GSLs38. In R. sativus, we identified one copy of FMOGS-OX2, which catalyses the S-oxygenation of glucoraphasatin and converts glucoraphasatin into glucoraphenin. The results of the GSL content analyses performed in previous studies21,22,48–50 demonstrated that glucoraphasatin is predominant in the roots and leaves of R. sativus, whereas glucoraphenin accumulates heavily in the seeds. Correspondingly, FMOGS-OX2 was highly expressed in the silique and minimally expressed in roots. The tissue-specific differential expression of FMOGS-OX2 clearly results in the different predominant GSLs in various tissues of R. sativus. The FMOGS-OX2 gene of R. sativus shows biotechnological potential, as the cancer-preventive properties of the plant involve sulforaphene, which is the catabolite of glucoraphenin51. Additionally, we found no AOP2 or AOP3 genes in R. sativus, as reported by Mitsui et al.29. The loss of these two genes prevents the conversion of S-oxygenated and hydroxyalkyl GSLs into downstream GSLs, which is the reason for the accumulation of glucoraphasatin and glucoraphenin in R. sativus.

In addition, two transcription factors (MYB76, MYB115) were lost in R. sativus. Although aliphatic GSL levels will increase with increased MYB76 expression levels, a knockout mutant of MYB76 was reported to exhibit no significant change in GSLs in A. thaliana 52. MYB115 and MYB118 are functionally redundant and interact to control the expression of GLS genes39. Therefore, the loss of MYB76 and MYB115 does not completely abolish GSL biosynthesis. While MYB115 and MYB118 negatively regulate aliphatic GSLs in A. thaliana 39, the double myb115-myb118 mutant exhibits increased levels of most of the short-chain aliphatic GSLs with the exception of 4-methylthiobutyl GSL (glucoerucin, GER)39. Moreover, GER content increased in the single myb115 mutant but significantly decreased in the myb118 mutant39. That is, MYB118 promotes the accumulation of GER but decreases the levels of other aliphatic GSLs in A. thaliana. GER is a precursor of the predominant aliphatic GSLs in R. sativus, B. rapa and B. oleracea 53. Several studies have shown that aliphatic GSLs, especially GER and its downstream products, are highly predominant in seeds in the three Brassica vegetables. In addition, in other organs, the percentages of aliphatic GSLs are decreased18,19,53. Considering that MYB118 was expressed only in the silique, we inferred that its silique-specific expression results in the high accumulation of aliphatic GSLs in seeds of these three vegetables. Nonetheless, further work is required to elucidate the molecular basis of the regulation of GSL biosynthesis through MYB118.

The ESP and NSP proteins divert the myrosinase-catalysed hydrolysis of an aliphatic GSL from the formation of ITC to the production of epithionitrile and nitrile54. O’Hare et al. found that there were no ESP proteins in R. sativus 34. We identified one ESP gene showing no detectable expression in any organ of R. sativus, indicating that its function might have been lost in R. sativus. We also observed one NSP5 gene with no expression profile in the roots and minimal expression in other organs, and we found no NSP1-4 genes within the R. sativus genome. The non-expression of the ESP gene and the lack of expression of the NSP gene in the roots and the leaves were inferred to be the major reasons for the accumulation of distinctive beneficial isothiocyanates, such as sulforaphene, rather than epithionitriles or nitriles.

Materials and Methods

Data resources

The A. thaliana genome and annotation data were downloaded from TAIR10 (http://www.arabidopsis.org/)55. B. rapa and B. oleracea assembly and annotation data were downloaded from the BRAD database (http://brassicadb.org/brad/)56. The genome data for A. lyrata were obtained from the JGI database. The three whole-genome sequences of R. sativus sequenced by Zhang et al.35, Mitsui et al.29 and Jeong et al.30 were downloaded from the BRAD database56, NODAI Radish genome database (http://www.nodai-genome-d.org/)29 and Radish Genome database (http://www.radish-genome.org/)30, respectively. B. rapa and B. oleracea RNA-seq data were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database with accession numbers GSE43245 and GSE42891, respectively. R. sativus RNA-seq data35 are available at EMBL/NCBI/SRA (PRJNA413464).

GSL gene identification in R. sativus

The GSL genes of A. thaliana have been reported previously9,27,57,58 and were aligned with corresponding protein sets from R. sativus 35, B. rapa 59, B. oleracea 28 and A. lyrata 60 using BLASTP (E-value ≤ 1 × 10−10, identity ≥55).

Analysis of GSL genes in R. sativus

To detect the generation mechanism of the expanded genes, we identified syntenic orthologues using SynOrths based on both sequence similarity and the collinearity of flanking genes61. We identified tandem duplicate genes using the same standard with GSL gene identification, and only one unrelated gene was allowed to exist between the two genes in a tandem array62. CLUSTALW63 was employed for sequence alignment. The phylogenetic tree of the ST gene family members of R. sativus and other species was constructed using the neighbour-joining method with MEGA (version 7.0.21) software64.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Plan of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2016YFD0100204-02, 2013BAD01B04), the 973 Program (2013CB127000), the 863 program (2012AA021801-04, 2012AA100101) and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-XTCX2016017, 2016016-4-4, 2016001-5-3).

Author Contributions

X.L. conceived the research and designed the experiments. J.W. and Y.Q. conducted the experiments. J.W. and X.Y. analysed the data, J.W. and Y.Q. wrote the paper. X.C., X.Z., D.S., H.W., J.S. and H.H. participated in the experiment. X.L., Z.Y. and X.W. were involved in manuscript preparation. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Jinglei Wang and Yang Qiu contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-16306-4.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Brader G, Mikkelsen MD, Halkier BA, Tapio Palva E. Altering glucosinolate profiles modulates disease resistance in plants. Plant J. 2006;46:758–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halkier BA, Gershenzon J. Biology and biochemistry of glucosinolates. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006;57:303–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JH, Lee BW, Schroeder FC, Jander G. Identification of indole glucosinolate breakdown products with antifeedant effects on Myzus persicae (green peach aphid) Plant J. 2008;54:1015–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Kensler TW, Cho C-G, Posner GH, Talalay P. Anticarcinogenic activities of sulforaphane and structurally related synthetic norbornyl isothiocyanates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:3147–3150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fahey JW, Zalcmann AT, Talalay P. The chemical diversity and distribution of glucosinolates and isothiocyanates among plants. Phytochemistry. 2001;56:5–51. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodman, J. E., Karol, K. G., Price, R. A. & Sytsma, K. J. Molecules, morphology, and Dahlgren’s expanded order Capparales. Syst. Bot. 289–307 (1996).

- 7.Clarke DB. Glucosinolates, structures and analysis in food. Anal. Methods-UK. 2010;2:310–325. doi: 10.1039/b9ay00280d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sønderby IE, et al. A systems biology approach identifies a R2R3 MYB gene subfamily with distinct and overlapping functions in regulation of aliphatic glucosinolates. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sønderby IE, Geu-Flores F, Halkier BA. Biosynthesis of glucosinolates-gene discovery and beyond. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenwick GR, Heaney RK, Mullin WJ, VanEtten CH. Glucosinolates and their breakdown products in food and food plants. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 1983;18:123–201. doi: 10.1080/10408398209527361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bones AM, Rossiter JT. The myrosinase-glucosinolate system, its organisation and biochemistry. Physiol. Plantarum. 1996;97:194–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1996.tb00497.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chumala P, Suchy M. Phytoalexins from Thlaspi arvense, a wild crucifer resistant to virulent Leptosphaeria maculans: structures, syntheses and antifungal activity. Phytochemistry. 2003;64:949–956. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00441-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zasada I, Ferris H. Nematode suppression with brassicaceous amendments: application based upon glucosinolate profiles. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2004;36:1017–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2003.12.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banga, O. Radish: Raphanus sativus (Cruciferae). Evolution of Crop Plants. NW Simmonds, ed (1976).

- 15.Baenas N, et al. Metabolic activity of radish sprouts derived isothiocyanates in drosophila melanogaster. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:251. doi: 10.3390/ijms17020251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matusheski NV, Jeffery EH. Comparison of the bioactivity of two glucoraphanin hydrolysis products found in broccoli, sulforaphane and sulforaphane nitrile. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2001;49:5743–5749. doi: 10.1021/jf010809a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanschen FS, et al. The Brassica epithionitrile 1-cyano-2, 3-epithiopropane triggers cell death in human liver cancer cells in vitro. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015;59:2178–2189. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong E, Kim SJ, Kim GH. Identification and quantitative determination of glucosinolates in seeds and edible parts of Korean Chinese cabbage. Food chem. 2011;128:1115–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.11.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhandari SR, Jo JS, Lee JG. Comparison of glucosinolate profiles in different tissues of nine Brassica crops. Molecules. 2015;20:15827–15841. doi: 10.3390/molecules200915827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maldini, M. et al. Identification and quantification of glucosinolates in different tissues of Raphanus raphanistrum by liquid chromatography tandem-mass spectrometry. J. Food Compos. Anal. (2016).

- 21.Carlson DG, Daxenbichler M, VanEtten C, Hill C, Williams P. Glucosinolates in radish cultivars. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1985;110:634–638. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciska E, Honke J, Kozłowska H. Effect of light conditions on the contents of glucosinolates in germinating seeds of white mustard, red radish, white radish, and rapeseed. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2008;56:9087–9093. doi: 10.1021/jf801206g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashimoto S, Miyazawa M, Kameoka H. Volatile flavor sulfur and nitrogen constituents of Brassica rapa L. J. Food Sci. 1982;47:2084–2085. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1982.tb12958.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanschen, F. S., & Schreiner, M. Isothiocyanates, nitriles, and epithionitriles from glucosinolates are affected by genotype and developmental stage in Brassica oleracea varieties. Front. Plant Sci. 8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Blažević I, Mastelić J. Glucosinolate degradation products and other bound and free volatiles in the leaves and roots of radish (Raphanus sativus L.) Food Chem. 2009;113:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.07.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sønderby IE, Geu-Flores F, Halkier BA. Biosynthesis of glucosinolates–gene discovery and beyond. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang H, et al. Glucosinolate biosynthetic genes in Brassica rapa. Gene. 2011;487:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, S. et al. The Brassica oleracea genome reveals the asymmetrical evolution of polyploid genomes. Nat. Commun. 5 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Mitsui, Y. et al. The radish genome and comprehensive gene expression profile of tuberous root formation and development. Sci Rep. 5 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Jeong YM, et al. Elucidating the triplicated ancestral genome structure of radish based on chromosome-level comparison with the Brassica genomes. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2016;129:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00122-016-2708-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kakizaki, T. et al. A 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase mediates the biosynthesis of glucoraphasatin in radish. Plant Physiol. pp-01814 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Kissen R, Bones AM. Nitrile-specifier proteins involved in glucosinolate hydrolysis in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol. Chem. 2009;284:12057–12070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807500200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lambrix V, Reichelt M, Mitchell-Olds T, Kliebenstein DJ, Gershenzon J. The Arabidopsis epithiospecifier protein promotes the hydrolysis of glucosinolates to nitriles and influences Trichoplusia ni herbivory. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2793–2807. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.12.2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Hare, T. J. et al. International symposium on plants as food and medicine: the utilization. XXVII international horticultural congress-IHC2006. 765, 237–244.

- 35.Zhang X, et al. A de novo genome of a Chinese radish cultivar. Hortic. Plant J. 2015;1:155–167. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sémon M, Wolfe KH. Consequences of genome duplication. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2007;17:505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrándiz C, Liljegren SJ, Yanofsky MF. Negative regulation of the SHATTERPROOF genes by FRUITFULL during Arabidopsis fruit development. Science. 2000;289:436–438. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5478.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hansen BG, Kliebenstein DJ, Halkier BA. Identification of a flavin-monooxygenase as the S-oxygenating enzyme in aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2007;50:902–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, Li B, Huai D, Zhou Y, Kliebenstein DJ. The conserved transcription factors, MYB115 and MYB118, control expression of the newly evolved benzoyloxy glucosinolate pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:343. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hara M, Fujii Y, Sasada Y, Kuboi T. cDNA cloning of radish (Raphanus sativus) myrosinase and tissue-specific expression in root. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000;41:1102–1109. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcd034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen S, et al. CYP79F1 and CYP79F2 have distinct functions in the biosynthesis of aliphatic glucosinolates in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003;33:923–937. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hansen CH, et al. Cytochrome p450 CYP79F1 from Arabidopsis catalyzes the conversion of dihomomethionine and trihomomethionine to the corresponding aldoximes in the biosynthesis of aliphatic glucosinolates. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:11078–11085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knill T, Reichelt M, Paetz C, Gershenzon J, Binder S. Arabidopsis thaliana encodes a bacterial-type heterodimeric isopropylmalate isomerase involved in both Leu biosynthesis and the Met chain elongation pathway of glucosinolate formation. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;71:227–239. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9519-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He Y, et al. A redox-active isopropylmalate dehydrogenase functions in the biosynthesis of glucosinolates and leucine in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;60:679–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gigolashvili T, et al. The plastidic bile acid transporter 5 is required for the biosynthesis of methionine-derived glucosinolates in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2009;21:1813–1829. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.066399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wentzell AM, et al. Linking Metabolic QTLs with network and cis-eQTLs controlling biosynthetic pathways. Plos Genet. 2007;3:1687–1701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li J, et al. Subclade of flavinmonooxygenases involved in aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:1721–1733. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.125757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barillari J, et al. Isolation of 4-methylthio-3-butenyl glucosinolate from Raphanus sativus sprouts (Kaiware Daikon) and its redox properties. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2005;53:9890–9896. doi: 10.1021/jf051465h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barillari J, Iori R, Rollin P, Hennion F. Glucosinolates in the subantarctic crucifer Kerguelen Cabbage (Pringlea antiscorbutica) J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:234–236. doi: 10.1021/np049822q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ishida M, et al. Small variation of glucosinolate composition in Japanese cultivars of radish (Raphanus sativus L.) requires simple quantitative analysis for breeding of glucosinolate component. Breeding Sci. 2012;62:63–70. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.62.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Juge N, Mithen RF, Traka M. Molecular basis for chemoprevention by sulforaphane: a comprehensive review. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007;64:1105–1127. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6484-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gigolashvili T, Engqvist M, Yatusevich R, Müller C, Flügge UI. HAG2/MYB76 and HAG3/MYB29 exert a specific and coordinated control on the regulation of aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2008;177:627–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yi G, et al. Root Glucosinolate profiles for screening of radish (Raphanus sativus L.) genetic resources. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2015;64:61–70. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kong XY, Kissen R, Bones AM. Characterization of recombinant nitrile-specifier proteins (NSPs) of Arabidopsis thaliana: Dependency on Fe(II) ions and the effect of glucosinolate substrate and reaction conditions. Phytochemistry. 2012;84:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huala E, et al. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): a comprehensive database and web-based information retrieval, analysis, and visualization system for a model plant. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:102–105. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cheng F, et al. BRAD, the genetics and genomics database for Brassica plants. BMC Plant biol. 2011;11:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bednarek P, et al. A glucosinolate metabolism pathway in living plant cells mediates broad-spectrum antifungal defense. Science. 2009;323:101–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1163732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grubb CD, Abel S. Glucosinolate metabolism and its control. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang X, et al. The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:1035–1039. doi: 10.1038/ng.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hu TT, et al. The Arabidopsis lyrata genome sequence and the basis of rapid genome size change. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:476–481. doi: 10.1038/ng.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Feng C, Jian W, Lu F, Wang X. Syntenic gene analysis between Brassica rapa and other Brassicaceae species. Front. Plant Sci. 2012;3:198. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu J, et al. Genome-wide comparative analysis of NBS-encoding genes between Brassica species and Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:3–3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Larkin MA, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.