Abstract

Psychrophiles are extremophilic organisms capable of thriving in cold environments. Proteins from these cold-adapted organisms can remain physiologically functional at low temperatures, but are structurally unstable even at moderate temperatures. Here, we report the crystal structure of adenylate kinase (AK) from the Antarctic fish Notothenia coriiceps, and identify the structural basis of cold adaptation by comparison with homologues from tropical fishes including Danio rerio. The structure of N. coriiceps AK (AKNc) revealed suboptimal hydrophobic packing around three Val residues in its central CORE domain, which are replaced with Ile residues in D. rerio AK (AKDr). The Val-to-Ile mutations that improve hydrophobic CORE packing in AKNc increased stability at high temperatures but decreased activity at low temperatures, suggesting that the suboptimal hydrophobic CORE packing is important for cold adaptation. Such linkage between stability and activity was also observed in AKDr. Ile-to-Val mutations that destabilized the tropical AK resulted in increased activity at low temperatures. Our results provide the structural basis of cold adaptation of a psychrophilic enzyme from a multicellular, eukaryotic organism, and highlight the similarities and differences in the structural adjustment of vertebrate and bacterial psychrophilic AKs during cold adaptation.

Introduction

Extremophiles are organisms that can thrive in extreme environmental conditions of various physical and chemical parameters such as temperature, pressure, pH, and salinity1–3. Among the extremophiles, psychrophiles and thermophiles, which are tolerant of low and high temperatures, respectively, have been of particular interest as they have potential in biotechnological applications2–5. Proteins isolated from psychrophilic and thermophilic organisms can remain physiologically functional at extreme temperatures, which are detrimental to mesophilic proteins from organisms living at moderate temperatures6–9. Hence, psychrophilic and thermophilic proteins are desirable for use in many academic and industrial settings that require biological activity at the extreme temperatures8,10–12.

To evaluate the molecular basis for the temperature adaptation of psychrophilic and thermophilic proteins, numerous comparative studies have performed comparisons with their mesophilic homologues13–18. Modifications of intramolecular interactions such as hydrogen bonds, electrostatic interactions, and hydrophobic contacts have been identified as the main structural mechanisms of cold and heat adaptation, but the various individual structural features change unpredictably to different extents in different proteins13–18. The alterations of intramolecular interactions are the results of structural adjustments that allow for appropriate flexibility to ensure physiological function at different temperatures6–8,18–21. Psychrophilic proteins tend to exhibit fewer intramolecular interactions than their mesophilic homologues, which, at low temperatures, would become too inflexible to perform the dynamic movements required for their biological functions8,11,16–18,21,22.

Previously, we reported the crystal structures, thermal denaturation midpoints (Tm’s), temperature-activity profiles, and molecular dynamics trajectories of homologous adenylate kinases (AKs) from psychrophilic, mesophilic, and thermophilic bacteria23–26. The thermal stabilities and temperature optima for catalytic activities of the enzymes scaled with the environmental temperatures of their source organisms23,25,26. The psychrophilic AK revealed the lowest apolar buried surface area of the trio23, suggesting that a reduction in the number of hydrophobic contacts played a role in cold adaptation, which is generally defined as high catalytic activity at low temperatures8,11,16,17. However, the residue substitution(s) responsible for its decreased thermal stability have not been identified.

AK is a small enzyme that catalyzes a reversible phosphoryl transfer reaction between ATP/AMP and two ADPs. The tertiary structure of AK can be subdivided into three domains: CORE, AMPbind, and LID27. The static CORE domain provides substrate-binding sites, and the dynamic AMPbind and LID domains close over the AMP and ATP sites, respectively, upon substrate binding28–30. AK is ubiquitous in all three kingdoms of life. Bacterial AKs are monomeric with a long LID domain31, whereas archaeal AKs form trimers containing a short LID domain32. Vertebrates have several AK isoforms. AK1 is the most abundant cytosolic AK isozyme, exists in a monomeric state, and contains a short LID domain33,34.

In this study, we solved the crystal structure of AK1 from the Antarctic fish Notothenia coriiceps (AKNc)35, and characterized its thermal stability and temperature–activity profile. To identify the structural adjustments important for its cold adaptation, AKNc was compared with homologous AKs from the following tropical fishes: Poecilia reticulata (AKPr)36, Xiphophorus maculatus (AKXm)37, and Danio rerio (AKDr)38, whose crystal structure was also determined in the present study. The habitat temperature of the Antarctic N. coriiceps (−1.5 to +1 °C)39 is significantly lower than typical living temperatures of the tropical species (>15 °C)40–42. Our results also highlight the similarities and differences in the structural changes related to temperature adaptation in vertebrate and bacterial AKs, indicating that the reduced thermal stability of psychrophilic enzymes may or may not be an adaptive trait depending on structural mechanism of catalytic activity.

Results

AKs from Antarctic and tropical fishes exhibited high sequence similarities but disparate thermal stabilities

The amino acid sequence of AKNc has been aligned with those of the three homologous AKs from tropical fishes in Fig. 1. The sequences of the Antarctic and tropical AKs exhibit high-level similarity. The sequence identity between AKNc and AKDr is 92%, and AKNc shares 94% sequence identities with the other two tropical AK homologues, AKXm and AKPr. These two tropical AKs are identical except at only one position (residue 184) and, interestingly, share lower sequence identities (90%) with the tropical AKDr than with the Antarctic AKNc. Notably, the N- and C-terminal regions are the most variable in the sequence alignment of the AKs. AKNc and AKDr differ by 15 residues, more than two thirds of which are located within 30 residues from the N- and C-termini of the amino acid sequence. Only 11 residues differ between AKNc and the other two tropical AKs, and six of them are found in the N- and C-terminal regions.

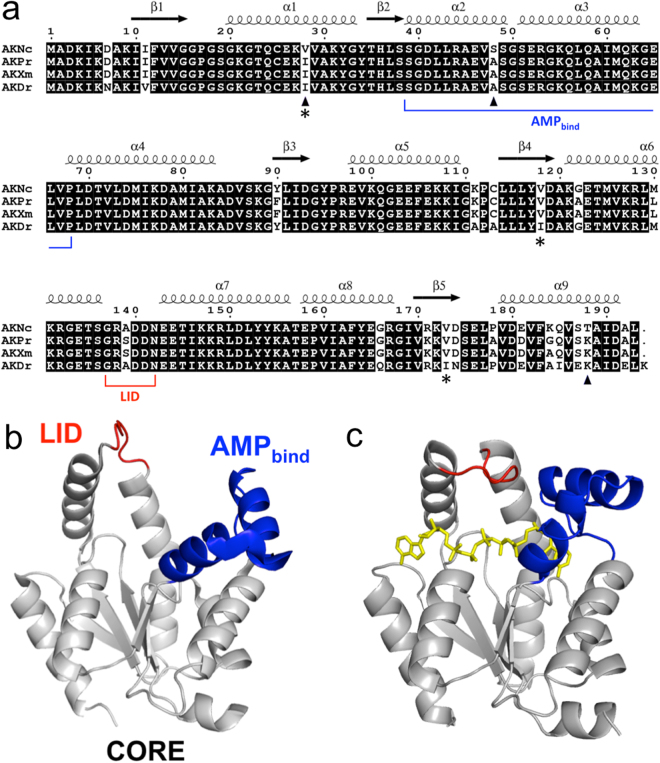

Figure 1.

Sequence and dynamics of AKs. (a) Sequence alignment of AKNc from the Antarctic fish N. coriiceps and its homologues from tropical fishes including AKDr. Secondary structural elements are indicated based on AKNc. Three positions (residues 28, 48, and 188) at which the amino acid is conserved in the three tropical AKs but not in AKNc are indicated by triangles. The three Val residues (Val28, Val118, and Val173) around which hydrophobic packing is not optimal in the AKNc are indicated by asterisks. Residues of the AMPbind domain (residues 39–68) and the LID (residues 137–142) are also indicated. The other residues belong to the CORE domain (residues 1–38, 69–136, and 143–193). (b,c) Structural dynamics of AK during a catalytic cycle. Open (b) and closed (c) conformations of AK are depicted using the crystal structures of porcine (Protein Data Bank code 3ADK) and human (Protein Data Bank code 1Z83) AK1 homologues, respectively. The CORE, AMPbind, and LID domains are shown in grey, blue, and red, respectively. Ap5A molecule bound to the active site is shown in yellow.

The Tm values of the AKs were measured by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy (Fig. S1). The Tm of AKNc was significantly lower than those of homologues from tropical fishes (Table 1), indicating the thermal stability of AKNc is substantially reduced compared with those of the other three AKs. Among the tropical AKs, AKDr was the most thermally stable. The difference in Tm between AKDr and AKNc was 11.3 °C. The Tm values of AKXm and AKPr were 9.2 °C and 7.0 °C, respectively, higher than that of AKNc. In a previous study of bacterial AKs, the Tm difference was only 4.3 °C between psychrophilic and mesophilic homologues23. These results suggest that the thermal stabilities of the fish AKs reflect the temperature preferences of their source organisms, as the thermal transition of the Antarctic AKNc occurred at a substantially lower temperature than those of its homologues from tropical fishes.

Table 1.

Tm values of WT and mutant AKs from the Antarctic and tropical fishes.

| AK | Mutation(s) | Tm (°C) | ΔTm (°C)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| AKNc | WT | 33.8 | 0.0 |

| V28I | 38.8 | 5.0 | |

| S48A | 36.0 | 2.2 | |

| V118I | 36.6 | 2.8 | |

| V173I | 36.2 | 2.4 | |

| T188K | 30.7 | −3.1 | |

| V118I/V173I | 41.4 | 7.6 | |

| V28I/V118I/V173I | 45.1 | 11.3 | |

| AKPr | WT | 40.8 | 7.0 |

| AKXm | WT | 43.0 | 9.2 |

| AKDr | WT | 45.1 | 11.3 |

| I28V/I118V/I173V | 36.2 | 2.4 |

aDifference from the Tm of WT AKNc.

Structural analyses revealed suboptimal hydrophobic packing in the central CORE domain of AKNc

To assess the structural basis of cold adaptation, we determined the crystal structures of AKNc and AKDr to resolutions of 1.99 and 1.75 Å, respectively, using molecular replacement. Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 2. The asymmetric units of both structures contain two independent AK monomers. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) values of the Cα atomic positions between the two monomers were only ~0.6 Å for both AKNc and AKDr, indicating that the two monomeric structures in the same asymmetric units are very similar. We hereafter describe only those (chain A’s), which exhibit lower average B factors.

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statisticsa.

| AKNc | AKDr | AKNc V28I/V118I/V173I | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | P41212 | C2 | P41212 |

| Unit cell parameters (Å) | a = b = 105.5, c = 84.3 | a = 100.6, b = 52.5, c = 89.3, | a = b = 105.4, c = 83.8 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0000 | 0.9793 | 0.9793 |

| Data collection statistics | |||

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.00-1.99 (2.06-1.99) | 50.00-1.75 (1.81-1.75) | 50.00-1.90 (1.97-1.90) |

| Number of reflections | 33142 (3227) | 41960 (4159) | 37833 (3703) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (100.0) | 99.8 (99.7) | 99.9 (100.0) |

| Rmerge b | 0.078 (0.491) | 0.115 (0.756) | 0.090 (0.781) |

| Redundancy | 14.1 (12.8) | 7.1 (7.0) | 7.1 (7.1) |

| Mean I/σ | 49.4 (7.5) | 19.6 (3.8) | 24.9 (3.5) |

| Refinement statistics | |||

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.00-1.99 | 50.00-1.75 | 50.00-1.90 |

| Rcryst c/Rfree d (%) | 17.1/20.8 | 18.6/22.9 | 17.5/21.1 |

| RMSD bonds (Å) | 0.022 | 0.020 | 0.022 |

| RMSD angles (deg) | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.4 |

| Average B factor (Å2) | 33.6 | 31.3 | 27.8 |

| Number of water molecules | 173 | 108 | 129 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 98.6 | 97.6 | 98.1 |

| Ramachandran allowed (%) | 1.4 | 2.4 | 1.9 |

aValues in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

bRmerge = ∑h∑|Ii(h) − < I(h) >|/∑h∑iIi(h), where Ii(h) is the intensity of an individual measurement of the reflection and < I(h) > is the mean intensity of the reflection.

cRcryst = ∑h||Fobs| − |Fcalc||/∑h|Fobs|, where Fobs and Fcalc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

dRfree was calculated as Rcryst using 5% of the randomly selected unique reflections that were omitted from structure refinement.

The chain folds of AKNc and AKDr are essentially identical to those of its homologues (Figs 2a, 3a and S2). The structures comprised the characteristic three-domain arrangement: the CORE (residues 1–38, 69–136, and 143–193), AMPbind (residues 39–68), and LID (residues 137–142) domains. The CORE domain consists of a five-stranded parallel β-sheet (β1–5) and seven α-helices (α1, α4–9), and the AMPbind domain includes two α-helices (α2, α3). The LID domain is a short loop connecting α6 and α7 helices, as is true of other AK1 structures. The co-crystallized ligand P1,P5-di(adenosine 5′)-pentaphosphate (Ap5A), which mimics both AMP and ATP substrates, is bound to the active site and covered by the AMPbind and LID domains, indicating that the crystal structures of AKNc and AKDr adopt the closed conformational state of AK28.

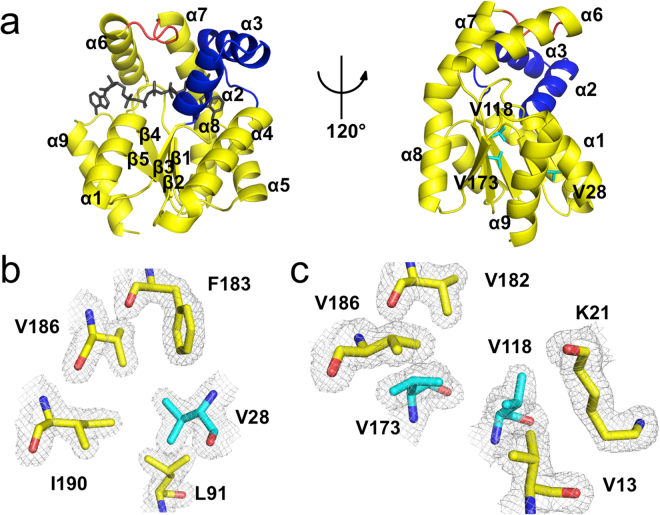

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of the Antarctic AKNc. (a) Overall structure of AKNc. The CORE (residues 1–38, 69–136, and 143–193), AMPbind (residues 39–68) and LID (residues 137–142) domains are shown in yellow, blue, and red, respectively. The co-crystallized Ap5A molecule bound to the active site is shown in black (left), but not in the 120°-rotated model (right), to reveal the AK structure more clearly. The three Val residues for which hydrophobic contacts are suboptimal are highlighted in cyan in stick representations (right). (b,c) Close-up views of the hydrophobic environment around Val28 (b) and Val118/Val173 (c). The Val residues interact hydrophobically with other residues in the CORE domain, but there is room for improvement in hydrophobic packing. The 2mFobs − DFcalc map is contoured at 1.0 σ.

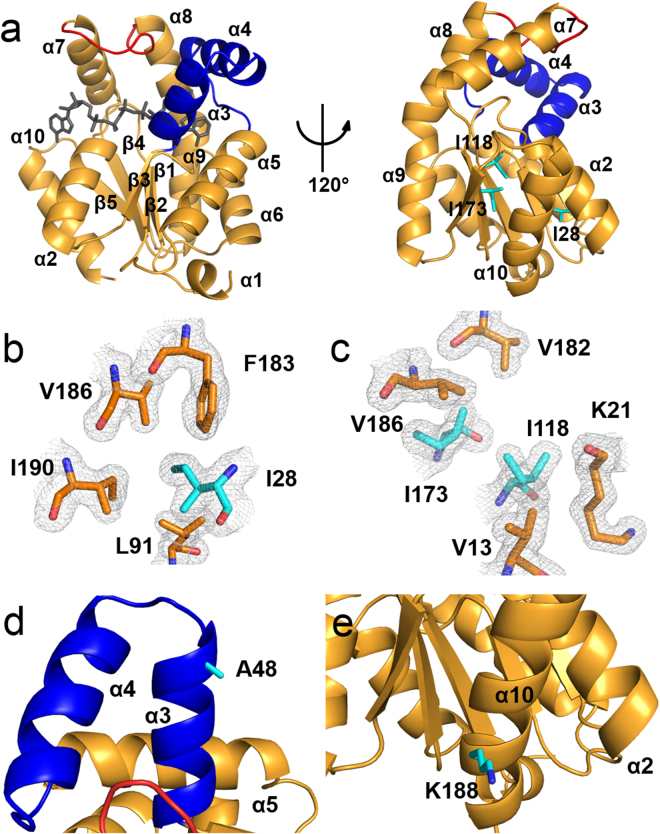

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of the tropical AKDr. (a) Overall structure of AKDr. The CORE (residues 1–38, 69–136, and 143–194), AMPbind (residues 39–68) and LID (residues 137–142) domains are shown in orange, blue, and red, respectively. The co-crystallized Ap5A molecule is shown in black. (b,c) Hydrophobic contacts of Ile28 (b) and Ile118/Ile173 (c) in the CORE domain of the AKDr structure. The three Ile residues are substituted to Val residues in AKNc. The 2mFobs−DFcalc map is contoured at 1.0 σ. (d,e) Close-up views of Ala48 (d) and Lys188 (e) in the crystal structure of AKDr. Ala48 and Lys188 are conserved among the three tropical AKs including AKDr, but not in AKNc. The side chains of Ala48 and Lys188 are exposed to the solvent, and do not interact closely with residues that are located distantly in the amino acid sequence.

To identify key structural features for the cold adaptation of AKNc, we focused on amino acid residues conserved among the three tropical AKs, but not in the Antarctic AKNc. We found three such positions (residues 28, 48, and 188) in the sequence alignment (Fig. 1a). The three AKs from the tropical fishes including AKDr have Ile28, Ala48, and Lys188 at these positions, whereas AKNc has Val28, Ser48, and Thr188. We thought that these residue substitutions might be related to the temperature adaptation of the AKs. In the structure of AKNc, Val28 in the N-terminal α1 helix interacts closely (<4 Å) with conserved hydrophobic residues in the β3 strand (Leu91) and the C-terminal α9 helix (Phe183, Val186, and Ile190) (Fig. 2b). Moreover, the Val-to-Ile mutation at this position (residue 28) found in the tropical homologues is expected to improve the hydrophobic packing in the CORE domain. In the structure of AKDr, the longer side chain of Ile28 enhances the hydrophobic contacts with the residues in β3 and α9, and interacts more closely with hydrophobic residues in β1 and β4 (Fig. 3b). In contrast, Ala48 and Lys188 are largely exposed to the solvent in the AKDr structure, and do not make close contacts with residues that are located distantly in the polypeptide (Fig. 3d,e), indicating that mutations at these two positions in AKNc may not exert significant effects on the intramolecular interactions.

In the CORE domain of AKNc, we found two additional Val residues (Val118 and Val173), around which hydrophobic packing could be improved by mutations (Fig. 2c). At these positions, AKXm and AKPr also have Val residues, but AKDr, which is the most thermally stable of the three tropical AKs, has Ile residues. Val118 and Val173 of AKNc are adjacent to each other (<4 Å) in β4 and β5, respectively. Their side chains are found in the hydrophobic interior of the CORE domain, making contacts with residues in β1, α1, and α9 such as Val13, Lys21, Val182, and Val186. However, there is room for improvement in hydrophobic packing around the two Val residues (Val118 and Val173). Val-to-Ile mutations at these positions would most likely result in closer hydrophobic contacts with residues in the β strands (β1, β4, β5) and the two terminal helices (α1, α9). In the crystal structure of AKDr, Ile118 and Ile173 improve CORE packing cooperatively by increasing hydrophobic interactions between them as well as with other residues (Fig. 3c). Taken together, the structural analyses of AKNc and AKDr suggest that hydrophobic CORE packing is not optimal in AKNc, and is important in thermal stability of fish AKs.

Improvement in hydrophobic CORE packing increased thermal stability of AKNc

To investigate the role of hydrophobic packing around the three Val residues in temperature adaptation, we generated a series of AKNc mutants, in which the Val residues were substituted to Ile residues individually or collectively, and measured their Tm values by CD spectroscopy (Table 1 and Fig. S1). The V28I mutation increased the thermal stability of AKNc considerably, as indicated by a 5.0 °C increase in Tm compared with that in the wild-type (WT). The enhancement of thermal stability resulting from the other two individual Val-to-Ile mutations was relatively modest. The V118I and V173I mutations increased the Tm of AKNc by 2.8 °C and 2.4 °C, respectively. However, the AKNc mutant with both the V118I and the V173I mutations exhibited an increase in Tm of 7.6 °C relative to the WT AKNc. This value is greater than the sum of Tm increases conferred by the V118I and V173I mutations individually, indicating a synergistic effect of the two mutations on the overall thermal stability. This is consistent with the structural analyses since the two residues are located close to each other (<4 Å) in the crystal structures (Fig. 2c).

The three Val-to-Ile mutations in combination resulted in the greatest thermal stability of AKNc (Table 1 and Fig. S1). The Tm value of the V28I/V118I/V173I mutant was 11.3 °C higher than that of the WT AKNc, and was identical to that of AKDr, the most thermally stable homologue of the three tropical AKs. This observation suggests that the suboptimal hydrophobic packing around the three Val residues in the CORE domain is important for the reduced thermal stability of AKNc compared with that of its homologues from tropical fishes. We also tested the role of the hydrophobic CORE packing in thermal stability in the opposite direction. We produced an AKDr mutant in which Ile28, Ile118 and Ile173 residues were replaced with Val residues, and determined its Tm value (Table 1 and Fig. S1). The reverse triple mutation significantly reduced the thermal stability of AKDr, as indicated by a decrease in Tm of 8.9 °C relative to the WT enzyme, confirming the importance of the CORE packing in the overall stability of the fish AKs.

We also measured the thermal stabilities of S48A and T188K mutants of AKNc to test the effect of residue substitution at these positions. The three tropical AKs have Ala48 and Lys188, but AKNc has Ser48 and Thr188. The Tm value of the S48A mutant was 2.2 °C higher than that of the WT AKNc, and the T188K mutation decreased the thermal stability of AKNc by 3.1 °C (Table 1). These results support the hypothesis that residues at these two positions may not be critical for overall thermal stability as they are not involved in intramolecular interactions connecting distant regions of the polypeptide, and suggest that the three Val residues play more important roles in the cold adaptation of AKNc.

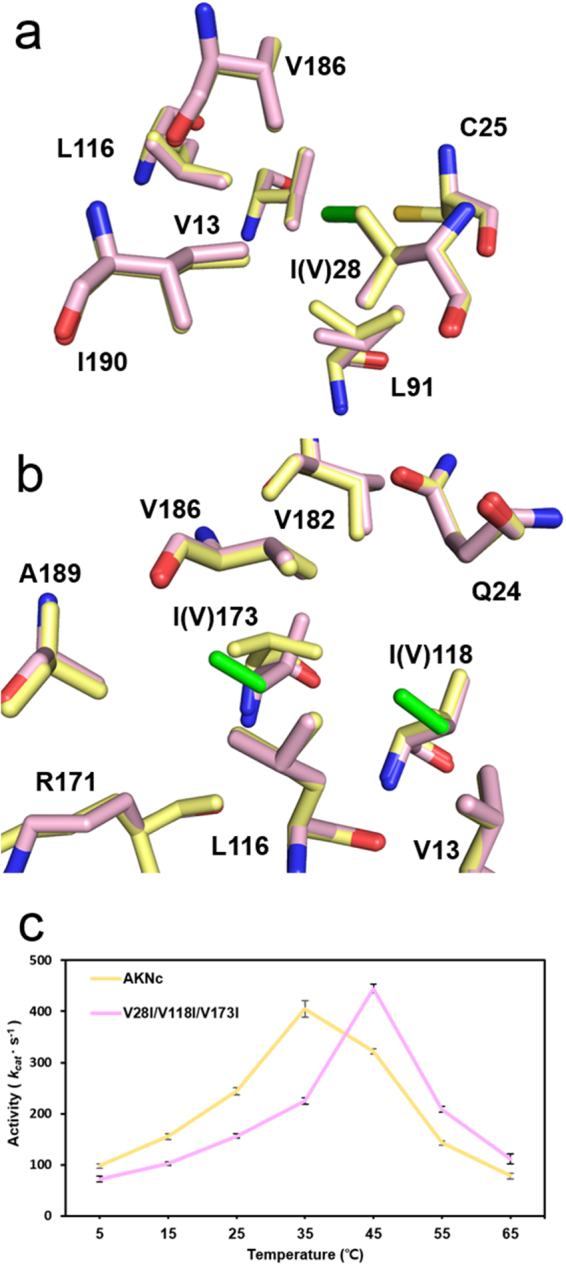

To confirm that thermal stabilization caused by the Val-to-Ile mutations resulted from the optimized hydrophobic CORE packing, we determined the crystal structure of a V28I/V118I/V173I mutant of AKNc (Fig. S3). Data collection and refinement statistics are listed in Table 2. The overall tertiary structure of the mutant was essentially identical to that of the WT. The RMSD value of Cα atoms between the WT AKNc and the mutant was 0.15 Å. In the mutant structure, the conformations of the residues neighboring the mutated Ile28 residue were almost indistinguishable from those around Val28 in the WT AKNc structure (Fig. 4a). This allows the added terminal methyl group (Cδ1) of the Ile28 side chain to interact hydrophobically with other residues in the CORE domain—such as Val13, Cys25, Leu91, Leu116, Val186, and Ile190—indicating the enhancement of the hydrophobic packing by the V28I mutation. The crystal structure of the AKNc mutant also revealed that the V118I and V173I mutations optimized the hydrophobic packing in the CORE of AKNc (Fig. 4b). The conformation of Ile118 was essentially identical to that of Val118 in the WT structure, with the exception of the extra methyl group (Cδ1) in its side chain, which makes additional hydrophobic contacts with Val13, Gln24, Leu116, and Val186 in β1, α1, β4, and α9, respectively, in the mutant structure. In contrast, the side chain conformation of the mutated Ile173 residue was distinct from that of Val173 in WT AKNc. The χ1 dihedral angle along the bond between the Cα and Cβ atoms of Ile173 was rotated ~120° relative to that of Val173 in the WT AKNc structure. The flipped side chain of Ile173 interacts hydrophobically with residues in β4, β5, and α9, including Leu116, Arg171, Val182, Val186, and Ala189. The hydrophobic contact between the two mutated residues (Ile118 and Ile173) is enhanced by the extension and conformational change of their side chains. The structural comparison of the WT and mutant AKNc revealed that the three Val-to-Ile mutations optimized the packing of the hydrophobic interior of the CORE domain.

Figure 4.

Optimization of hydrophobic CORE packing by Val-to-Ile substitutions in AKNc. (a,b) V28I (a) and V118I/V173I (b) substitutions improve CORE packing with other hydrophobic residues in the crystal structure of the V28I/V118I/V173I mutant of AKNc (pink). The three mutated Ile residues are highlighted in green. The structure of WT AKNc (yellow) is aligned with that of the mutant. (c) Temperature dependence of activity of WT AKNc and the V28I/V118I/V173I mutant. The activities in the direction of ATP formation were measured at various temperatures. The Val-to-Ile mutations reduced the catalytic activity at low temperatures (5–35 °C). At each temperature, three independent measurements were made. Data are represented as mean ± standard error of mean.

Since our structural analyses are based on the Ap5A-bound structures, we also made Tm measurements of the WT and the triple mutant AKs in the presence of Ap5A (Table 3 and Fig. S1). The addition of Ap5A caused significant Tm increases for the AKs, indicating that the Ap5A binding stabilized the enzymes. Notably, the order in Tm was maintained for the WT and mutant enzymes regardless of the presence of Ap5A, but the Tm difference between them was reduced. For example, the V28I/V118I/V173I mutant of AKNc displayed higher Tm than the WT AKNc by 11.3 °C without Ap5A, whereas the mutant was more thermally stable than the WT enzyme only by 4.5 °C in the presence of Ap5A. In the previous studies of bacterial AK variants, the effects of Tm increase by applying multiple stabilization principles together were not strictly cumulative, and the magnitude of the Tm enhancement varied depending on the backgrounds to which the stabilizing factors were added24,26,43. Thus, the results from the Tm measurements with Ap5A seem to be consistent with the previous analyses, and, more importantly, confirm the validity of our structural analyses for the structural determinants of thermal stability.

Table 3.

Tm values of fish AKs in the presence of Ap5A.

| AK | Mutations | Tm (°C) | ΔTm (°C)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| AKNc | WT | 55.8 | 0.0 |

| V28I/V118I/V173I | 60.3 | 4.5 | |

| AKDr | WT | 61.8 | 6.0 |

| I28V/I118V/I173V | 56.5 | 0.7 |

aDifference from the Tm of WT AKNc in the presence of Ap5A

Optimization of hydrophobic CORE packing also affected catalytic function of AKNc

To examine the temperature dependence of the catalytic activity, we performed activity assays of WT AKNc and the mutant containing the three Val-to-Ile mutations (V28I/V118I/V173I) at various temperatures (Fig. 4c). The catalytic activity of the WT enzyme in terms of kcat peaked at 35 °C and decreased afterwards, compared to 45 °C for the mutant AKNc, which was more catalytically active than the WT AKNc at high temperatures (45 °C and 55 °C). The increase of the activity at high temperature could be a consequence of the enhanced thermal stability of the mutant AKNc. The inactivation of the enzymes at high temperatures most likely resulted from thermal denaturation. However, the mutant showed considerably decreased activity at low temperatures (5–35 °C) compared to the WT enzyme, which cannot be explained by the difference in thermal stability between the WT and mutant AKs. It seems that the improvement in hydrophobic CORE packing by the Val-to-Ile mutations increased the structural stability at high temperatures and decreased the catalytic activity at low temperatures. The stabilizing mutations might make the enzyme too rigid, and the dynamic motion required for its catalytic function might be impeded at low temperatures due to the reduced flexibility.

The activity assays of AKDr and its I28V/I118V/I173V mutant also showed consistent results (Fig. S4). The AKDr mutant exhibited increased catalytic activities at low temperatures (5 °C and 35 °C) compared to the WT enzyme, and the temperature of maximum activity decreased (35 °C). However, the magnitude of the activity change at low temperatures by mutation was not as significant as in AKNc. This suggests that AKDr contains extra structural feature(s) maintaining the rigidity of its structure in addition to the hydrophobic interactions involving the Ile residues. In the crystal structure of AKDr, we identified a salt bridge connecting between Arg171 and Glu192 (Fig. S5), which is substituted to Ala192 in AKNc. Consistently, the Tm increase (11.3 °C) of AKNc by the three Val-to-Ile mutations was greater than the Tm decrease (8.9 °C) of AKDr by the reverse triple mutation (Table 1), supporting the role of the salt bridge. Taken together, our results suggest that activity and stability of fish AKs are inversely correlated, and disruption of hydrophobic packing may be a structural mechanism of cold adaptation as it could increase catalytic activity at low temperatures.

Discussion

AKNc is useful for research on cold adaptation of psychrophilic enzymes for several reasons. The source organism of AKNc is the Antarctic fish N. coriiceps; therefore, the enzyme originated from a multicellular, eukaryotic psychrophile, whereas most previously characterized psychrophilic proteins were from psychrophilic microorganisms4,5. The conformational switching required for its enzymatic function also makes AKNc an attractive system to study the role of protein dynamics in cold adaptation as the maintenance of appropriate local and/or global motion is crucial for functioning at extreme temperatures. AK is a small protein that undergoes relatively large conformational changes upon substrate binding and product release (Fig. 1b), and has long been used as a model system for studying connections between structure, function, and dynamics28–30,32,44–49.

The ‘corresponding state’ hypothesis first proposed by Somero postulates that homologous proteins originated from organisms living at different environmental temperatures have comparable flexibilities and activities at their physiologically relevant temperatures20,50. Although this hypothesis has widely been accepted by the scientific community, whether the reduced stability of psychrophilic proteins is a consequence of maintaining the conformational flexibility necessary for functional activity at low temperatures, or a result of a lack of evolutionary pressure, remains unclear51. In previous studies of bacterial AKs, the AK variants generated exhibited both thermal stability at high temperatures and sufficient catalytic activity at low temperatures, suggesting that activity at low temperatures can be achieved without sacrificing stability, and thus the low stability of psychrophilic proteins is not an adaptive trait46,52. However, in this study, the stabilizing Val-to-Ile mutations in AKNc reduced the activity at low temperatures, indicating that stability and activity are coupled, and the decreased thermal stability of AKNc might be required for sufficient catalytic activity in cold environments.

This contradiction likely results from structural differences in the LID domain of AKNc and its bacterial homologues. In AKNc, the LID is a short loop of less than 10 residues (Figs 1a and 2a), whereas the bacterial AKs have LID domains of >30 residues that include several β-strands (Fig. S6). The long LID domain is crucial for the function of bacterial AKs, as LID opening was the rate-limiting step in catalysis47, and conformational heterogeneity within the LID domain was important in functional adaptation53,54. Hence, it is conceivable that stability and activity are governed independently by different domains of bacterial AKs with the large LID domains, but not in short isoforms such as AKNc. In a previous study, swapping of the CORE domains of AKs from mesophilic and thermophilic bacteria affected Tm values significantly, but did not affect the temperature dependence of activity, highlighting the spatial separation of stability and activity control in bacterial AKs52. Hence, for cold adaptation of bacterial AKs, residue substitutions in the LID domain are likely required to alter the LID dynamics, which are closely related to catalytic activity.

In the sequence alignment (Fig. 1a), the N- and C-terminal regions exhibited the greatest variability between AKNc and its homologues from tropical fishes. This observation suggests that these areas play more crucial roles in the temperature adaptation of AKs. The important role of the N- and C-terminal residues in overall thermal stability has already been noted for archaeal and bacterial AKs23,24,44,55. The chain folds of the AK homologues revealed that the first and last α helices (α1 and α9 in AKNc, respectively) in the amino acid sequence are located in close proximity28,31,32. Numerous polar and hydrophobic intramolecular interactions have been identified between the two terminal regions or involving residues from one of them23,24,44. In a previous study of archaeal AKs from the genus Methanococcus, chimeric AKs were constructed by exchanging the N- and C-terminal residues between mesophilic and hyperthermophilic homologues, and exhibited significant changes in Tm values (~20 °C) compared to the WT proteins55. Experimental evolution for thermal stabilization of a mesophilic bacterial AK by Shamoo and co-workers resulted in the generation of stable AK variants containing mutations at six different positions, five of which were located within the first or last 30 residues of the amino acid sequence56.

The Ile-to-Val mutations in the CORE domain of AKDr resulted in a significant decrease in thermal stability (Table 1). Several previous studies of the stabilization of the mesophilic Bacillus subtilis AK (AKBs) have reported the importance of hydrophobic CORE packing in thermal stability26. Comparative analyses with a thermophilic homologue enabled identification of a residue substitution (T179M) that enhanced hydrophobic interactions in the CORE domain23, which increased thermal stability when introduced to AKBs26. The experimental evolution of AKBs also generated several mutations (Q16L, T179I, and A193V)56 that stabilized the mesophilic target by improving the CORE packing57. Stable AKBs variants were previously designed based on a bioinformatic method of optimizing local structural entropy, an empirical descriptor of sequence heterogeneity58. The resulting AKBs mutants displayed increased apolar buried surface areas in the CORE domain, indicating the enhancement of hydrophobic contacts43. In a computational prediction followed by experimental validation, Wilson and co-workers tested 100 AKBs mutants and demonstrated that substantial thermal stabilization could be achieved by repacking of the hydrophobic CORE59.

In the present study, we discovered suboptimal hydrophobic packing in the CORE domain of the Antarctic fish AK. Comparative and mutational analyses demonstrated that imperfect hydrophobic CORE packing indeed results in reduced thermal stability and a shift in the temperature-activity profile. Our results suggest that modification of hydrophobic contacts is a key structural feature important for the cold adaptation of psychrophilic proteins, and may be used to engineer psychrophilicity in mesophilic enzymes.

Methods

Cloning, expression, and purification

Synthetic genes of the WT fish AK1 proteins were cloned into a pET28a vector with an N-terminal (His)6-maltose binding protein (MBP) tag and a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site. Mutant genes were generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using mismatched primers. Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells containing these constructs were cultured in LB medium at 37 °C until the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.7. Protein expression was then induced by the addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside, followed by incubation at 17 °C for 16 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in purification buffer (500 mM NaCl, 3 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% (w/v) glycerol, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0). After sonication and centrifugation, the supernatant was loaded onto a 5 mL HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare, USA) equilibrated with purification buffer. The column was washed with purification buffer, and bound proteins were eluted by applying a linear gradient of imidazole (up to 500 mM). The (His)6-MBP tag was cleaved by TEV protease and separated using a HisTrap HP column. The proteins were further purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare, USA) equilibrated with size-exclusion chromatography buffer (300 mM NaCl, 3 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 5% (w/v) glycerol, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.0).

Measurement of Tm values

Tm values of AKs were determined by CD spectroscopy, as described previously26. CD traces at 220 nm were measured for 0.5 mg/mL AKs in 10 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.0 with or without 0.2 mM Ap5A. A Chirascan-plus CD Spectrometer (Applied Photophysics, UK) was used with a scanning rate of 1 °C/min. CD data were analyzed based on the protocol developed by John and Weeks60. Average values of three CD measurements at each temperature were differentiated to yield differential denaturation curves, which were fitted to parameters including Tm using a two-state transition model.

Crystallization and structure determination

The WT and mutant AKNc proteins were crystallized under identical conditions. Their crystals were grown at 4 °C by the sitting-drop method from 18 mg/mL protein and 4 mM Ap5A in buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.0) mixed with an equal amount of reservoir solution (50% (v/v) polyethylene glycol 400, 200 mM lithium sulfate, 100 mM sodium acetate pH 4.5). The crystals were cryoprotected in the reservoir solution supplemented with 15% (v/v) ethylene glycol and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The AKDr crystals were obtained at 20 °C by the sitting-drop method from 20 mg/mL protein and 4 mM Ap5A in buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.0) mixed with an equal amount of reservoir solution (2.5 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M sodium acetate pH 4.6). The crystals were cryoprotected in the reservoir solution supplemented with 20% (v/v) ethylene glycol and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Diffraction data from the AKNc and AKDr crystals were collected at 100 K at the beamlines 5 C and 7 A of the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory. Diffraction images were processed with HKL200061. PHASER was used for molecular replacement phasing62. The structure of human AK1 (Protein Data Bank code 1Z83) was used as a starting model for the WT AKNc. Molecular replacement solutions for AKDr and the AKNc mutant were found with the WT AKNc structure. The final structures were completed using alternate cycles of manual fitting in COOT63 and refinement in REFMAC564. The stereochemical quality of the final models was assessed using MolProbity65.

Temperature-dependent activity assay

AK activity was measured at multiple temperatures in the direction of ATP formation as described previously, with minor modifications52. The enzymatic reaction was started by the addition of AK (1.1 ng/mL final concentration) to the reaction mixture (2.5 mM ADP, 1 mM glucose, 0.4 mM NADP+, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4). After incubation at the indicated temperatures for 5 min, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.5 mM Ap5A. The amount of ATP produced by the reaction was determined by ATP-dependent NADP+ reduction to NADPH using hexokinase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase at room temperature. Average values of three independent measurements were reported with standard errors.

Data availability

The atomic coordinates and structure factors were deposited in the Protein Data Bank66. The Protein Data Bank accession codes of AKNc, AKDr, and the V28I/V118I/V173I mutant of AKNc are 5X6 K, 5XZ2, and 5XRU, respectively.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the beamlines 5 C and 7 A of the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory for their support with data collection. This work was supported by the Cooperative Research Program for Agricultural Science & Technology Development funded by Rural Development Administration (PJ01111201) and the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2016R1D1A1A09916821).

Author Contributions

E.B. conceived and supervised the research. S.M. and J.K. performed the experiments. All authors analyzed the results, and wrote the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Sojin Moon and Junhyung Kim contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-16266-9.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rothschild LJ, Mancinelli RL. Life in extreme environments. Nature. 2001;409:1092–1101. doi: 10.1038/35059215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raddadi N, Cherif A, Daffonchio D, Neifar M, Fava F. Biotechnological applications of extremophiles, extremozymes and extremolytes. Applied microbiology and biotechnology. 2015;99:7907–7913. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalmaso GZ, Ferreira D, Vermelho AB. Marine extremophiles: a source of hydrolases for biotechnological applications. Marine drugs. 2015;13:1925–1965. doi: 10.3390/md13041925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Margesin R, Miteva V. Diversity and ecology of psychrophilic microorganisms. Research in microbiology. 2011;162:346–361. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Amico S, Collins T, Marx JC, Feller G, Gerday C. Psychrophilic microorganisms: challenges for life. EMBO reports. 2006;7:385–389. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feller G. Protein stability and enzyme activity at extreme biological temperatures. Journal of physics. Condensed matter: an Institute of Physics journal. 2010;22:323101. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/22/32/323101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reed CJ, Lewis H, Trejo E, Winston V, Evilia C. Protein adaptations in archaeal extremophiles. Archaea. 2013;2013:373275. doi: 10.1155/2013/373275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santiago M, Ramirez-Sarmiento CA, Zamora RA, Parra LP. Discovery, Molecular Mechanisms, and Industrial Applications of Cold-Active Enzymes. Frontiers in microbiology. 2016;7:1408. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarmiento F, Peralta R, Blamey JM. Cold and Hot Extremozymes: Industrial Relevance and Current Trends. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology. 2015;3:148. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2015.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siddiqui KS. Some like it hot, some like it cold: Temperature dependent biotechnological applications and improvements in extremophilic enzymes. Biotechnology advances. 2015;33:1912–1922. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feller G. Psychrophilic enzymes: from folding to function and biotechnology. Scientifica. 2013;2013:512840. doi: 10.1155/2013/512840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavicchioli R, et al. Biotechnological uses of enzymes from psychrophiles. Microbial biotechnology. 2011;4:449–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2011.00258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unsworth LD, van der Oost J, Koutsopoulos S. Hyperthermophilic enzymes–stability, activity and implementation strategies for high temperature applications. The FEBS journal. 2007;274:4044–4056. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Razvi A, Scholtz JM. Lessons in stability from thermophilic proteins. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1569–1578. doi: 10.1110/ps.062130306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vieille C, Zeikus GJ. Hyperthermophilic enzymes: sources, uses, and molecular mechanisms for thermostability. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews: MMBR. 2001;65:1–43. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.1.1-43.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerday C. Psychrophily and catalysis. Biology. 2013;2:719–741. doi: 10.3390/biology2020719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Struvay C, Feller G. Optimization to low temperature activity in psychrophilic enzymes. International journal of molecular sciences. 2012;13:11643–11665. doi: 10.3390/ijms130911643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lockwood BL, Somero GN. Functional determinants of temperature adaptation in enzymes of cold- versus warm-adapted mussels (Genus Mytilus) Molecular biology and evolution. 2012;29:3061–3070. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniel RM, Danson MJ. A new understanding of how temperature affects the catalytic activity of enzymes. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2010;35:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Somero GN. Adaptation of enzymes to temperature: searching for basic “strategies”. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Part B, Biochemistry & molecular biology. 2004;139:321–333. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feller G. Life at low temperatures: is disorder the driving force? Extremophiles. 2007;11:211–216. doi: 10.1007/s00792-006-0050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gianese G, Bossa F, Pascarella S. Comparative structural analysis of psychrophilic and meso- and thermophilic enzymes. Proteins. 2002;47:236–249. doi: 10.1002/prot.10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bae E, Phillips GN., Jr. Structures and analysis of highly homologous psychrophilic, mesophilic, and thermophilic adenylate kinases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28202–28208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bae E, Phillips GN., Jr. Identifying and engineering ion pairs in adenylate kinases. Insights from molecular dynamics simulations of thermophilic and mesophilic homologues. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30943–30948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504216200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bae E, Moon S, Phillips GN. Molecular dynamics simulation of a psychrophilic adenylate kinase. J Korean Soc Appl Bi. 2015;58:209–212. doi: 10.1007/s13765-015-0033-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moon S, Jung DK, Phillips GN, Jr, Bae E. An integrated approach for thermal stabilization of a mesophilic adenylate kinase. Proteins. 2014;82:1947–1959. doi: 10.1002/prot.24549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulz GE. Structural and functional relationships in the adenylate kinase family. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1987;52:429–439. doi: 10.1101/SQB.1987.052.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerstein M, Schulz G, Chothia C. Domain closure in adenylate kinase. Joints on either side of two helices close like neighboring fingers. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:494–501. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller CW, Schlauderer GJ, Reinstein J, Schulz GE. Adenylate kinase motions during catalysis: an energetic counterweight balancing substrate binding. Structure. 1996;4:147–156. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(96)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vonrhein C, Schlauderer GJ, Schulz GE. Movie of the structural changes during a catalytic cycle of nucleoside monophosphate kinases. Structure. 1995;3:483–490. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller CW, Schulz GE. Structure of the complex between adenylate kinase from Escherichia coli and the inhibitor Ap5A refined at 1.9 A resolution. A model for a catalytic transition state. J Mol Biol. 1992;224:159–177. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90582-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vonrhein C, Bonisch H, Schafer G, Schulz GE. The structure of a trimeric archaeal adenylate kinase. J Mol Biol. 1998;282:167–179. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukami-Kobayashi K, Nosaka M, Nakazawa A, Go M. Ancient divergence of long and short isoforms of adenylate kinase: molecular evolution of the nucleoside monophosphate kinase family. FEBS Lett. 1996;385:214–220. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panayiotou C, Solaroli N, Karlsson A. The many isoforms of human adenylate kinases. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2014;49:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shin SC, et al. The genome sequence of the Antarctic bullhead notothen reveals evolutionary adaptations to a cold environment. Genome biology. 2014;15:468. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0468-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kunstner A, et al. The Genome of the Trinidadian Guppy, Poecilia reticulata, and Variation in the Guanapo Population. PloS one. 2016;11:e0169087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schartl M, et al. The genome of the platyfish, Xiphophorus maculatus, provides insights into evolutionary adaptation and several complex traits. Nature genetics. 2013;45:567–572. doi: 10.1038/ng.2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howe K, et al. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature. 2013;496:498–503. doi: 10.1038/nature12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnston II, Guderley H, Franklin C, Crockford T, Kamunde C. Are Mitochondria Subject to Evolutionary Temperature Adaptation? The Journal of experimental biology. 1994;195:293–306. doi: 10.1242/jeb.195.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laudien H, Schlieker V. Temperature-Dependence of Courtship Behavior in the Male Guppy, Poecilia-Reticulata. J Therm Biol. 1981;6:307–314. doi: 10.1016/0306-4565(81)90019-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matthews M, Trevarrow B, Matthews J. A virtual tour of the Guide for zebrafish users. Lab animal. 2002;31:34–40. doi: 10.1038/5000140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Portner HO, Peck MA. Climate change effects on fishes and fisheries: towards a cause-and-effect understanding. Journal of fish biology. 2010;77:1745–1779. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moon S, Bannen RM, Rutkoski TJ, Phillips GN, Jr., Bae E. Effectiveness and limitations of local structural entropy optimization in the thermal stabilization of mesophilic and thermophilic adenylate kinases. Proteins. 2014;82:2631–2642. doi: 10.1002/prot.24627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Criswell AR, Bae E, Stec B, Konisky J, Phillips GN., Jr. Structures of thermophilic and mesophilic adenylate kinases from the genus. Methanococcus. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:1087–1099. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00655-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eisenmesser EZ, Bosco DA, Akke M, Kern D. Enzyme dynamics during catalysis. Science. 2002;295:1520–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.1066176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen V, et al. Evolutionary drivers of thermoadaptation in enzyme catalysis. Science. 2017;355:289–294. doi: 10.1126/science.aah3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolf-Watz M, et al. Linkage between dynamics and catalysis in a thermophilic-mesophilic enzyme pair. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:945–949. doi: 10.1038/nsmb821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henzler-Wildman KA, et al. A hierarchy of timescales in protein dynamics is linked to enzyme catalysis. Nature. 2007;450:913–916. doi: 10.1038/nature06407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Henzler-Wildman KA, et al. Intrinsic motions along an enzymatic reaction trajectory. Nature. 2007;450:838–844. doi: 10.1038/nature06410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Somero GN. Temperature Adaptation of Enzymes - Biological Optimization through Structure-Function Compromises. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1978;9:1–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.09.110178.000245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldstein RA. The evolution and evolutionary consequences of marginal thermostability in proteins. Proteins. 2011;79:1396–1407. doi: 10.1002/prot.22964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bae E, Phillips GN., Jr. Roles of static and dynamic domains in stability and catalysis of adenylate kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2132–2137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507527103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schrank TP, Bolen DW, Hilser VJ. Rational modulation of conformational fluctuations in adenylate kinase reveals a local unfolding mechanism for allostery and functional adaptation in proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16984–16989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906510106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schrank TP, Wrabl JO, Hilser VJ. Conformational heterogeneity within the LID domain mediates substrate binding to Escherichia coli adenylate kinase: function follows fluctuations. Topics in current chemistry. 2013;337:95–121. doi: 10.1007/128_2012_410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haney PJ, Stees M, Konisky J. Analysis of thermal stabilizing interactions in mesophilic and thermophilic adenylate kinases from the genus Methanococcus. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28453–28458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Counago R, Chen S, Shamoo Y. In vivo molecular evolution reveals biophysical origins of organismal fitness. Molecular cell. 2006;22:441–449. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miller C, et al. Experimental evolution of adenylate kinase reveals contrasting strategies toward protein thermostability. Biophys J. 2010;99:887–896. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.04.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bae E, Bannen RM, Phillips GN., Jr. Bioinformatic method for protein thermal stabilization by structural entropy optimization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9594–9597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800938105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Howell SC, Inampudi KK, Bean DP, Wilson CJ. Understanding thermal adaptation of enzymes through the multistate rational design and stability prediction of 100 adenylate kinases. Structure. 2014;22:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.John DM, Weeks K. M. van’t Hoff enthalpies without baselines. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1416–1419. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.7.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. In Methods in Enzymology Vol. 276 (eds C. W. Jr. Carter & R. M. Sweet) 307-326 (Academic Press, 1997). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. Journal of applied crystallography. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berman HM, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The atomic coordinates and structure factors were deposited in the Protein Data Bank66. The Protein Data Bank accession codes of AKNc, AKDr, and the V28I/V118I/V173I mutant of AKNc are 5X6 K, 5XZ2, and 5XRU, respectively.