Abstract

The purpose of the study is to describe epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) with special focus on the disease in nonusers of contact lenses (CLs). This study was a perspective based on authors’ experience and review of published literature. AK accounts for 2% of microbiology-proven cases of keratitis. Trauma and exposure to contaminated water are the main predisposing factors for the disease. Association with CLs is seen only in small fraction of cases. Contrary to classical description experience in India suggests that out of proportion pain, ring infiltrate, and radial keratoneuritis are seen in less than a third of cases. Majority of cases present with diffuse infiltrate, mimicking herpes simplex or fungal keratitis. The diagnosis can be confirmed by microscopic examination of corneal scraping material and culture on nonnutrient agar with an overlay of Escherichia coli. Confocal microscopy can help diagnosis in patients with deep infiltrate; however, experience with technique and interpretation of images influences its true value. Primary treatment of the infection is biguanides with or without diamidines. Most patients respond to medical treatment. Corticosteroids play an important role in the management and can be used when indicated after due consideration to established protocols. Surgery is rarely needed in patients where definitive management is initiated within 3 weeks of onset of symptoms. Lamellar keratoplasty has been shown to have good outcome in cases needing surgery. Since the clinical features of AK in nonusers of CL are different, it will be important for ophthalmologists to be aware of the scenario wherein to suspect this infection. Medical treatment is successful if the disease is diagnosed early and management is initiated soon.

Keywords: Acanthamoeba keratitis, deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty, in vivo confocal microscopy, nonusers of contact lens, radial keratoneuritis, ring infiltrate, sclerokeratitis

Acanthamoeba are ubiquitous microorganisms and are considered opportunistic pathogens in humans. These have been implicated in a variety of systemic infections including the eye. The first case of Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) was described in the year 1974 from the UK.[1] From India, Sharma et al. published the first case.[2,3] Since then, many authors have published their experience with this disease and information has been compiled in review articles.[4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] Thus, there has been substantial growth in the knowledge about the disease. However, nearly all review articles on this topic have been published from the Western world with primary focus on contact lens (CL)-associated keratitis. In India and most developing countries where CLs are not popular trauma is the most common predisposing factor and patients of AK suffer from prolonged and significant morbidity from delay in diagnosis due to lack of awareness and misunderstanding about clinical signs and symptoms among physicians and non-availability of anti-Acanthamoeba drugs. Therefore, we decided to write this review article with the following learning objectives:

Summarize key features of AK and highlight differences between CL- and non-CL-associated keratitis

Describe clinical situations under which to suspect infection by Acanthamoeba

Describe ancillary clinical and laboratory tests for confirmation of the diagnosis including the role and limitations of in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM)

Discuss medical management including the indications and management of corticosteroid therapy

Summarize indications of surgical treatment including the role and limitations of deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK)

Discuss management of sclerokeratitis – a painful complication of the disease.

We recently analyzed 231 cases of AK managed at our center from 2012 to 2015 (unpublished data). In this article, we will present the data from this large series as well as review of the published literature to give practical perspective of the disease with primary focus on the disease in non-CL users.

Epidemiology

Classically, AK is described to be associated with CLs. However, the experience in India and other developing countries as well as countries with high prevalence of CL-related keratitis clearly suggests that the disease occurs even without associated use of CLs.[11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]

In India, Acanthamoeba accounts for 2% of all cases of culture-positive corneal ulcers at tertiary eye care centers.[12,13,14] Trauma and exposure to contaminated water or soil are the important predisposing factors of AK not associated with CL use.[15,16,17,18] Additional risk factors are the use of contaminated water as home water supply,[19,20,21,22] warmer weather,[21,23] and poor socioeconomic conditions.[15] AK has also been reported after surgical trauma including penetrating keratoplasty (PK) and radial keratotomy and laser refractive surgery.[4,24,25]

Acanthamoeba keratitis in contact lens users

Although AK comprises of <5% of CL-related microbial keratitis, 80–85% cases of AK in the UK, the United States, and other developed Asian countries with high prevalence of CL uses are associated with CL uses.[9,26,27,28] The incidence is much higher in conventional soft CL users compared to those using daily wear rigid gas permeable lenses or planned replacement soft lenses. It is probably related to lens hygiene.[23,29] AK has also been reported with the use of orthokeratology lenses.[30]

AK is usually unilateral; however, there are reports of simultaneous affection of both eyes.[29,31] The cases occur all through the year, but there is some association with weather with increase in number of cases in summer and rainy season probably related to the increased contamination of water with the parasite. In India, the middle-aged individuals primarily engaged in outdoor activity and agriculture are most often affected by this disease.[14,15,16]

Clinical Features

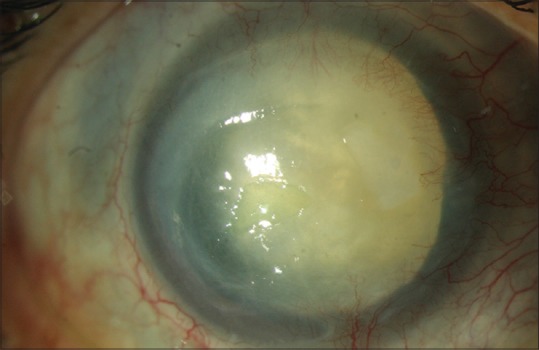

A textbook description of AK comprises of history of CL-wear, out of proportion pain, radial keratoneuritis, and ring infiltrate [Fig. 1]. However, one must remember that all patients with Acanthamoeba keratitis do not present with these classical symptoms and signs. Acanthamoeba infection of cornea is seen even in individuals with no history of CL wear as highlighted in epidemiology section. Reports from the Indian subcontinent and South America suggest that trauma and consequent exposure to contaminated water are the most important risk factors of AK in developing nations. Analysis of 231 cases (unpublished data) managed at our center between 2008 and 2013 showed that CL wear was the risk factor in only 3.5% cases. The population at risk of this infection, therefore, primarily comprised of agricultural workers and manual laborers. Publications from other centers in India also observed similar trends.[14,15,17]

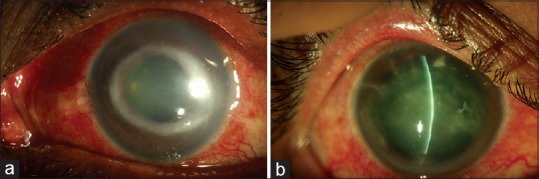

Figure 1.

Classical clinical features of Acanthamoeba keratitis – radial keratoneuritis (a); ring infiltrate (b)

The clinical presentation of AK is also highly variable. Out of proportion pain was not a prominent feature in our series and was seen in only one-fourth (n = 52, 23%) of patients. Radial keratoneuritis was seen in 6 (2.7%) cases while ring infiltrate was seen in 74 (33%) cases. Our case series as well as cases published from other centers suggest that corneal signs vary depending partly on the duration of the disease. Early cases present with punctuate epithelial erosions, anterior stromal haze, nummular keratitis, and variable stromal edema associated with keratic precipitates on endothelium [Fig. 2]. It is not surprising that many early cases are misdiagnosed as herpes simplex viral keratitis and treated accordingly. The presence of inflamed corneal nerves (radial keratoneuritis) is a pathognomonic clinical sign and should prompt the diagnosis of Acanthamoeba. If undiagnosed early, the disease progresses to develop classical ring-shaped infiltrate, necrotizing keratitis or diffuse infiltrative keratitis (features described in delayed presentation).

Figure 2.

Nonclassical clinical features of Acanthamoeba keratitis – epitheliopathy with geographic or dendritic configuration (a and b); nummular keratitis (c); nonulcerative stromal keratitis (d)

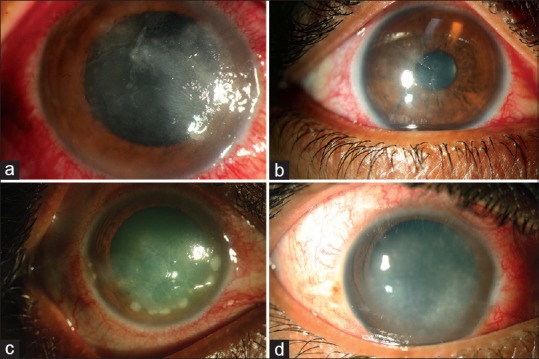

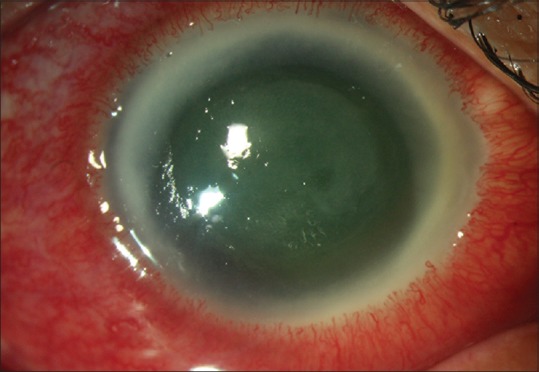

The clinical picture in patients presenting with advanced disease is characterized by ring infiltrate; dry-looking infiltrate mimicking fungal keratitis; diffuse infiltrate or ulcerative keratitis [Fig. 3]. In our case series, 74 (33%) patients presented with ring infiltrate while 141 (64%) cases presented with diffuse infiltrate. Two most common misdiagnosis made on the 1st day were herpes simplex virus (HSV) stromal keratitis and fungal keratitis. The series along with other published case series clearly highlight that absence of out of proportion pain, history of CL wear, radial keratoneuritis, or ring infiltrate do not rule out Acanthamoeba. This knowledge is very important in making clinical diagnosis of this relatively rare disease.

Figure 3.

Corneal picture of cases presenting late with advanced disease – ring infiltrate (a); necrotizing stromal keratitis (b); dry raised infiltrate mimicking fungal keratitis (c)

Clinical diagnosis

Since AK is often misdiagnosed, it will be important to be familiar with clinical scenario wherein to suspect Acanthamoeba etiology. They are as follows:

Patient presenting with corneal infiltrates associated with inflamed corneal nerves – these are linear structures with inflammation of adjoining stroma continuous with limbus and may have branching at central end [Fig. 1a]

Patients of chronic keratitis (history in weeks or months) associated with ring infiltrate [Fig. 1b]

Patients with suspected HSV keratitis not responding to anti-HSV therapy

Patients with ulcerative keratitis not responding to antibacterial or antifungal therapy.

All these patients must be subjected to laboratory tests for establishing the diagnosis.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Conventional laboratory procedures

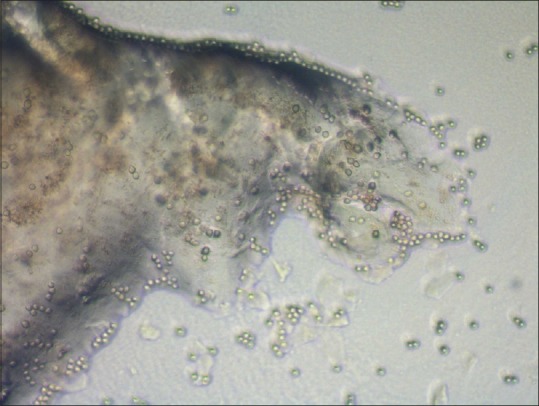

The laboratory diagnosis of Acanthamoeba is performed using the same protocol as used for detection of bacteria and fungi with minor modifications. The protocol includes a combination of microscopic examination of smears and inoculation of scraped specimen on various culture media that allow growth of bacteria, fungi, and Acanthamoeba and is described in detail in our earlier publication.[32] The Acanthamoeba cysts are seen as double-walled structure with inner wall being hexagonal on microscopic examination of smears stained with calcofluor-white or Gram stain and provide immediate diagnosis [Fig. 4]. The culture confirmation on nonnutrient agar with Escherichia coli overlay may take 1–3 days [Fig. 5]. The medium, however, should be incubated for up to 2 weeks before concluding it as a negative culture.[4]

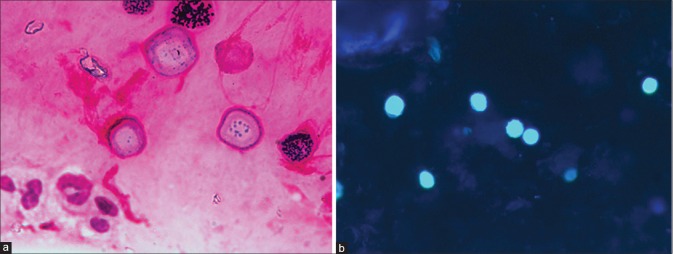

Figure 4.

Microscopic features of Acanthamoeba cyst in corneal scraping – Gram stain (a) and calcofluor-white (b). Note hexagonal inner wall of the cysts

Figure 5.

Culture of Acanthamoeba on nonnutrient agar with an overlay of Escherichia coli. Clear tracks on the lawn of Escherichia coli suggests migrating trophozoites that feed on bacteria

Patients with deep infiltrate and negative corneal scrapings might need corneal biopsy. The biopsy material is processed similar to corneal scrapings in microbiology laboratory. For histopathology sections, a variety of staining protocols have been described in the literature. However, most staining procedures such as calcofluor-white, Gram, Giemsa, fluorescein-conjugated lectin, hematoxylin, and eosin delineate the cyst of Acanthamoeba very well showing the characteristic morphology of polygonal, double-walled structure with central nucleus.[33,34,35] Trophozoites, on the other hand, may be difficult to distinguish from inflammatory cells.[16,36] Immunostaining with either indirect fluorescent antibody[37,38] or immunoperoxidase technique[36,39] has also been described. These stains can be used on corneal scrapings as well as corneal tissue sections.

Molecular methods of diagnosis

A number of molecular methods for the diagnosis of AK have been described. Most of these methods are based on amplification of 18S rDNA. Evaluation of molecular methods with conventional microbiology showed that the molecular methods are effective but have sensitivity similar to conventional microbiology.[40] Therefore, these tests have not been very popular in clinics. These are often used for identification of the parasite to subspecies level for understanding pathobiology and epidemiology.

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification, a newly developed highly specific, efficient, and less time-consuming DNA amplification technique which rapidly amplifies target DNA sequences under isothermal conditions, was evaluated, using 18S rDNA gene for specific detection of Acanthamoeba from corneal scraping samples, and was found particularly suitable for a rapid and accurate diagnosis of AK.[41] It takes 2–3 h lesser than polymerase chain reaction and thus offers a rapid, highly sensitive and specific, simple, and affordable diagnostic modality for patients suspected of AK, especially in resource-limited settings.

Confocal microscopy for Acanthamoeba keratitis

In past decade, a lot of enthusiasm has been seen for the use of IVCM for etiological diagnosis of corneal infections.[42,43,44,45,46,47] IVCM is a noninvasive imaging technique that allows direct visualization of pathogens including Acanthamoeba cysts within the patient's corneal tissue. Two machines currently in clinical use are scanning slit IVCM (Confoscan, Nidek, Fremont, USA) and laser scanning IVCM (HRT3/RCM, Heidelberg, Germany). Using microbiology as gold standard, the reported sensitivity and specificity of the technique for the diagnosis of Acanthamoeba varies between 80% and 100%.[42] American academy of ophthalmology published a technology assessment report on the value of confocal microscopy and concluded that confocal microscopy holds the potential to provide instantaneously a diagnosis, especially in cases of Acanthamoeba and fungal keratitis.[48] IVCM is particularly useful for detecting organisms in deep corneal infiltrates inaccessible to scraping. More recently, IVCM findings have also been correlated to the prognosis – the presence of clusters or chains of cysts has been found to be independently associated with a poor prognosis.

However, one needs to exercise caution – the diagnostic accuracy is strongly dependent on the experience of the observer.[49] Further, the technique requires cooperation of patients, which at times becomes difficult in patients suffering from painful condition such as keratitis.

Treatment

Medical management

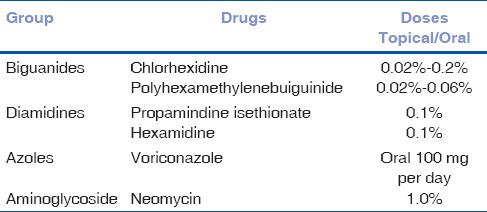

Table 1 lists drugs that have been used in the management of AK. However, none of the drugs effective in medical management are licensed for the use for AK treatment. The goals of medical therapy include the eradication of viable cysts and trophozoites and rapid resolution of the associated inflammatory response.

Table 1.

List of Anti-acanthamoeba drugs and doses

As regards in vitro activity, Acanthamoeba trophozoites are sensitive to most available chemotherapeutic agents (antibiotics, antiseptics, antifungals, antiprotozoals including metronidazole, antivirals, and antineoplastic agents). However, persistent infection is related to the presence of Acanthamoeba cysts, against which very few of these agents are effective.[50,51] Biguanides and diamidines have the best in vitro cysticidal activity and their use in clinical practice for the treatment of AK is supported by the vast in vivo experience in peer-reviewed literature.[4,5,6,7,8,52,53,54,55,56,57]

Therefore, topical biguanides with or without the addition of diamidines are the main stay of medical management of this disease. At our center, a combination of PHMB 0.02% and chlorhexidine 0.02% is used as the primary therapy.[16] Concentration of chlorhexidine and PHMB can be varied from 0.02% to 0.2% and from 0.02% to 0.06%, respectively. However, one needs to be aware of toxicity. The drops are administered every hour, day, and night, for 48 h initially, followed by hourly drops by day till the clinical signs of resolution are observed. Intensive early treatment is given because organisms may be more susceptible before cysts have fully matured. The frequency is reduced subsequently based on the clinical response. However, the impression of no response should be made only after adequate time has been allowed for anti-Acanthamoeba therapy, as duration of medical treatment is usually prolonged. Mean duration of treatment among patients cured of infection in our series was 128 days. In a multicenter study from the United Kingdom, the average duration of medical therapy was 6 months (range, 0.5–29 months).[23]

One should also be cautious about the toxicity of drugs, especially if preparations not meant of ophthalmic use are prescribed to patients.

Other drugs including neomycin and antifungal drugs are not effective and should not be relied on as sole therapy in the management of this disorder. There are reports of beneficial effect of concomitant use of antibiotics. The rationale for the use of antibiotics is the parasites thrive on bacteria, and phagosomes-containing bacteria have been demonstrated in the cytoplasm of the parasitic cells.[58,59,60] Similarly, there are reports on successful treatment of infection with the addition of voriconazole in patients not responding to conventional anti-Acanthamoeba treatment.[61] One can consider these additional therapies in patients not responding to conventional medical management.

Role of corticosteroids in the management of Acanthamoeba keratitis

The role of corticosteroid therapy in the management of AK is controversial.[62,63,64] While corticosteroids help control inflammation, in laboratory, they lead to transformation of cyst forms into trophozoites with consequent risk of worsening or recurrence of clinical disease.[65] On the other hand, trophozoites are more susceptible to anti-Acanthamoeba drugs. Despite this conflict, it is widely believed that corticosteroids have a definitive and beneficial role in the management of specific cases of AK provided these are used appropriately. The following are the indications of the use of corticosteroids in AK:

Occurrence and progressive increase in deep vascularization of cornea

Inflammatory complications of AK – scleritis, anterior chamber inflammation, persistent chronic keratitis

Severe out of proportion pain.

Take the following precautions while using corticosteroids: (a) Corticosteroid therapy is not commenced until 2 weeks of biguanide treatment has been completed. (b) Antiamoebic therapy is maintained throughout and continued after the steroids have been withdrawn. (c) Watch for recurrence of infection from viable cysts in follow-up visits. (d) Continue corticosteroid therapy until good control of inflammation is achieved. (e) Continue biguanides in low doses (four times per day) after discontinuation of corticosteroid therapy. (f) When the eye has been free of inflammation for 4 weeks, while using a biguanide alone, the condition is labeled as cured and all therapies are discontinued.

Surgical treatment

With achievement of high-cure rates with anti-Acanthamoeba therapy, the need for keratoplasty in active disease has reduced significantly.[52] However, a delay in diagnosis and initiation of specific therapy or its misdiagnosis as viral keratitis in the initial stages leads to more extensive disease. These cases may become too fulminant to be controlled medically or may develop descemetocele/perforation (which is not amenable to gluing) and may have to undergo surgical treatment.

The current indications for surgical treatment are (a) large infiltrate extending or threatening to involve limbus; (b) worsening on medical treatment; and (c) gross thinning or actual perforation.

Full-thickness PK has become less popular and is preferred only in cases of pre- and intra-operative corneal perforation.[66,67,68,69] Deep lamellar keratoplasty has been shown to be associated with better prognosis both for eradicating infection as well as graft survival.[70,71] We analyzed 23 cases of AK that underwent DALK at our center (unpublished data). There were no cases of recurrence of infection. However, 4 cases had detached Descemet membrane and required rebubbling. One patient had primary graft failure. Fifteen (65%) individuals had clear graft at the last follow-up. Three patients developed graft infiltrate of bacterial etiology, and 4 patients were lost to follow-up. Anshu et al. achieved successful eradication of infection in 8 out of the 9 eyes with therapeutic DALK in the first attempt and with a repeat procedure in the remaining eye with disease recurrence.[70] Sarnicola et al. performed deep lamellar keratoplasty in 11 cases early in the course of therapy with no episodes of failure or recurrence in follow-up.[71]

In view of success with medical therapy, keratoplasty should largely be avoided in active stages, and even if there is extensive corneal involvement, an attempt should be made to achieve control of infection medically as far as possible.[7] Further, all patients undergoing surgery should be started on antiamoebic therapy before surgery, which than is continued postoperatively to prevent recurrence of infection. We use PHMB and chlorhexidine eight time per day along with corticosteroids for 3 weeks after the surgery at which time anti-Acanthamoeba drugs can be discontinued if there is no recurrence of infection. Follow-up care and complications otherwise are similar to that for other cases of keratoplasty in inflamed eyes.

Complications

AK can be associated with extracorneal complications. Important ones are as follows:

Cataract

Cataract is seen in patients with severe and prolonged keratitis[72] [Fig. 6]. There are various theories of cataractogenesis in AK-toxicity from the use of topical anti-Acanthamoeba drugs, chronic inflammation, corticosteroids, and vascular thrombosis.

Figure 6.

Complication of Acanthamoeba keratitis: deep vascularization; cataract; dilated fixed pupil with peripheral anterior synechiae

Iris atrophy and persistent dilated fixed pupil

This is seen in some patients and is again attributed to severe inflammation and vascular thrombosis[73] [Fig. 6].

Scleritis

Scleritis in patients with AK is an painful agonizing but an uncommon complication that generally occurs in otherwise immune-competent individuals.[74] It is unrelated to direct invasion of Acanthamoeba and attributable to an inflammatory response. Dying organisms and degenerating amoebic cyst walls have been shown to elicit an adaptive immune response in the animal model of keratitis and are proposed to cause persistent corneal and scleral inflammation. Other theories for scleritis and other posterior segment inflammatory reactions are AK induced autoimmunity through molecular mimicry and T-cell response from corneal antigen-presenting cells resulting in inflammatory response in vascularized ocular tissues.[75,76] Patients who receive topical steroids before the diagnosis of AK, usually following misdiagnosis as herpes simplex keratitis, tend to develop scleritis more commonly than those who do not.

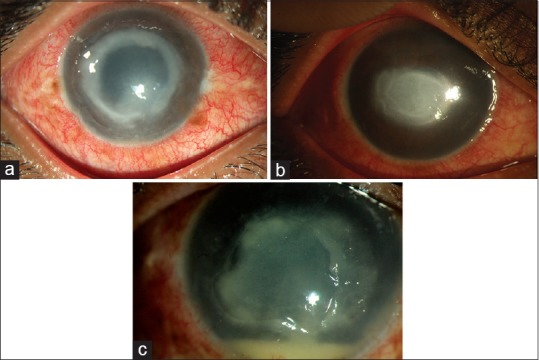

The clinical picture of scleritis is characterized by severe deep pain, globe tenderness, engorgement of episcleral and scleral vessels, and in advanced cases by nodular of diffuse thickening of sclera [Fig. 7]. The pain of scleritis is usually very severe and was one of the indications of enucleation before the treatment with immunosuppressive therapy was in practice. Iovieno et al. described a stepladder approach to the treatment of Acanthamoeba sclerokeratitis.[75] While milder form of scleritis gets controlled with topical steroids and oral NSAIDs, patients with severe disease require systemic immunosuppression in the form of oral steroids and steroid-sparing agents. The treatment is begun with intravenous methyl prednisolone 1-gram daily for 2–3 days along with oral prednisolone in the doses of 0.5–1 mg/kg/day. Unless there is rapid control of symptoms with oral prednisolone, steroid-sparing agents such as cyclosporine (3–7.5 mg/kg/day), mycophenolate (usually 1 g twice per day), or azathioprine (usually 100 mg oral daily) are added. In addition, all patients on systemic corticosteroid or immunosuppressive therapy are given oral antifungal therapy as prophylaxis against scleral invasion by trophozoites.[74,75] Treatment may last for months and is given in conjunction with antiamoebic medications, which are continued after discontinuation of immunosuppressive treatment.

Figure 7.

Clinical picture of a case of Acanthamoeba sclerokeratitis

Intraocular spread

Although there are cases showing Acanthamoeba cysts in choroid and vitreous,[76,77] it is believed that in most cases, the parasite remains restricted to cornea and it is rare to see extracorneal spread. The mechanism of extracorneal spread in the absence of perforation is unknown.

Prognosis

The prognosis of AK depends on the severity of the disease and the time duration between onset of symptoms and initiation of definitive treatment with anti-Acanthamoeba drugs.[78,79,80,81] Cases diagnosed and treated early respond well to medical treatment. Two large series from the UK suggest that outcomes are good in patients where treatment was initiated within 3 weeks of onset of symptoms. We also had similar experience.

Conclusion

Acanthamoeba is an uncommon cause of keratitis. However, the outcome of medical management is good if the disease is diagnosed early and definitive treatment is initiated. The epidemiology and clinical features of AK in India are different than what is described in the Western world. Ophthalmologists are advised to be familiar with these differences. Routine laboratory tests are good enough for its diagnosis. Unfortunately, the drugs are not available and need to be prepared from chemical solutions that are not approved for ophthalmic use. However, these have good safety records, and enough experience suggests that these can be dispensed with reasonable confidence.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jones DB, Visvesvara GS, Robinson NM. Acanthamoeba polyphaga keratitis and Acenthamoeba uveitis associated with fatal meningoencephalitis. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1975;95:221–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma S, Srinivasan M, George C. Acanthamoeba keratitis in non-contact lens wearers. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:676–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070070062035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma S, Srinivasan M, George C. Diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis – A report of four cases and review of literature. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1990;38:50–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Illingworth CD, Cook SD. Acanthamoeba keratitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42:493–508. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(98)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammersmith KM. Diagnosis and management of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:327–31. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000233949.56229.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Awwad ST, Petroll WM, McCulley JP, Cavanagh HD. Updates in Acanthamoeba keratitis. Eye Contact Lens. 2007;33:1–8. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e31802b64c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dart JK, Saw VP, Kilvington S. Acanthamoeba keratitis: Diagnosis and treatment update 2009. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:487–9900. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maycock NJ, Jayaswal R. Update on Acanthamoeba keratitis: Diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Cornea. 2016;35:713–20. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin J, Young AL, Hui M, Jhanji V. Acanthamoeba keratitis: 10-year study at a tertiary eye care center in Hong Kong. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2015;38:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2014.11.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qian Y, Meisler DM, Langston RH, Jeng BH. Clinical experience with Acanthamoeba keratitis at the cole eye institute, 1999-2008. Cornea. 2010;29:1016–21. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181cda25c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanhehco T, Colby K. The clinical experience of Acanthamoeba keratitis at a tertiary care eye hospital. Cornea. 2010;29:1005–10. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181cf9949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gopinathan U, Sharma S, Garg P, Rao GN. Review of epidemiological features, microbiological diagnosis and treatment outcome of microbial keratitis: Experience of over a decade. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2009;57:273–9. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.53051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basak SK, Basak S, Mohanta A, Bhowmick A. Epidemiological and microbiological diagnosis of suppurative keratitis in Gangetic West Bengal, Eastern India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2005;53:17–22. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.15280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lalitha P, Lin CC, Srinivasan M, Mascarenhas J, Prajna NV, Keenan JD, et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis in South India: A longitudinal analysis of epidemics. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012;19:111–5. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2011.645990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mascarenhas J, Lalitha P, Prajna NV, Srinivasan M, Das M, D’Silva SS, et al. Acanthamoeba, fungal, and bacterial keratitis: A comparison of risk factors and clinical features. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma S, Garg P, Rao GN. Patient characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment of non-contact lens related Acanthamoeba keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1103–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.10.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manikandan P, Bhaskar M, Revathy R, John RK, Narendran V, Panneerselvam K, et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis – A six year epidemiological review from a tertiary care eye hospital in South India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2004;22:226–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bashir G, Rizwi A, Shah A, Shakeel S, Fazili T. Acanthamoeba keratitis in Kashmir. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2005;48:417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kilvington S, Gray T, Dart J, Morlet N, Beeching JR, Frazer DG, et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis: The role of domestic tap water contamination in the United Kingdom. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:165–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houang E, Lam D, Fan D, Seal D. Microbial keratitis in Hong Kong: Relationship to climate, environment and contact-lens disinfection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95:361–7. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(01)90180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathers WD, Sutphin JE, Lane JA, Folberg R. Correlation between surface water contamination with amoeba and the onset of symptoms and diagnosis of amoeba-like keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:1143–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.10.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joslin CE, Tu EY, McMahon TT, Passaro DJ, Stayner LT, Sugar J, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of a Chicago-area Acanthamoeba keratitis outbreak. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:212–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radford CF, Lehmann OJ, Dart JK. Acanthamoeba keratitis: Multi-centre survey in England 1992–1996. National Acanthamoeba Keratitis Study Group. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:1387–92. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.12.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garg P, Chaurasia S, Vaddavalli PK, Muralidhar R, Mittal V, Gopinathan U, et al. Microbial keratitis after LASIK. J Refract Surg. 2010;26:209–16. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20100224-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balasubramanya R, Garg P, Sharma S, Vemuganti GK. Acanthamoeba keratitis after LASIK. J Refract Surg. 2006;22:616–7. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20060601-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butler TK, Males JJ, Robinson LP, Wechsler AW, Sutton GL, Cheng J, et al. Six-year review of Acanthamoeba keratitis in new South Wales, Australia: 1997-2002. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;33:41–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2004.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stapleton F, Keay L, Edwards K, Naduvilath T, Dart JK, Brian G, et al. The incidence of contact lens-related microbial keratitis in Australia. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1655–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Acharya NR, Lietman TM, Margolis TP. Parasites on the rise: A new epidemic of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:292–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radford CF, Minassian DC, Dart JK. Acanthamoeba keratitis in England and Wales: Incidence, outcome, and risk factors. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:536–42. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.5.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watt KG, Swarbrick HA. Trends in microbial keratitis associated with orthokeratology. Eye Contact Lens. 2007;33:373–7. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e318157cd8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee WB, Gotay A. Bilateral Acanthamoeba keratitis in Synergeyes contact lens wear: Clinical and confocal microscopy findings. Eye Contact Lens. 2010;36:164–9. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e3181db3508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma S, Athmanthan S. Diagnostic procedures in infectious keratitis. In: Nema HV, Nema N, editors. Diagnostic Procedures in Ophthalmology. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 2002. pp. 232–53. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilhelmus KR, Osato MS, Font RL, Robinson NM, Jones DB. Rapid diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis using calcofluor white. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:1309–12. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050210063026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robin JB, Chan R, Andersen BR. Rapid visualization of Acanthamoeba using fluorescein-conjugated lectins. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106:1273–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060140433047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas PA, Kuriakose T. Rapid detection of Acanthamoeba cysts in corneal scrapings by lactophenol cotton blue staining. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:168. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070040018011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma S, Athmanathan S, Ata-Ur-Rasheed M, Garg P, Rao GN. Evaluation of immunoperoxidase staining technique in the diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2001;49:181–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Epstein RJ, Wilson LA, Visvesvara GS, Plourde EG., Jr Rapid diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis from corneal scrapings using indirect fluorescent antibody staining. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:1318–21. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050210072028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Visvesvara GS, Mirra SS, Brandt FH, Moss DM, Mathews HM, Martinez AJ, et al. Isolation of two strains of Acanthamoeba castellanii from human tissue and their pathogenicity and isoenzyme profiles. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:1405–12. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.6.1405-1412.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blackman HJ, Rao NA, Lemp MA, Visvesvara GS. Acanthamoeba keratitis successfully treated with penetrating keratoplasty: Suggested immunogenic mechanisms of action. Cornea. 1984;3:125–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pasricha G, Sharma S, Garg P, Aggarwal RK. Use of 18S rRNA gene-based PCR assay for diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis in non-contact lens wearers in India. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3206–11. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.3206-3211.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mewara A, Khurana S, Yoonus S, Megha K, Tanwar P, Gupta A, et al. Evaluation of loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2017;35:90–4. doi: 10.4103/ijmm.IJMM_16_227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaddavalli PK, Garg P, Sharma S, Sangwan VS, Rao GN, Thomas R, et al. Role of confocal microscopy in the diagnosis of fungal and Acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chidambaram JD, Prajna NV, Larke NL, Palepu S, Lanjewar S, Shah M, et al. Prospective study of the diagnostic accuracy of thein vivo laser scanning confocal microscope for severe microbial keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:2285–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Labbé A, Khammari C, Dupas B, Gabison E, Brasnu E, Labetoulle M, et al. Contribution ofin vivo confocal microscopy to the diagnosis and management of infectious keratitis. Ocul Surf. 2009;7:41–52. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tu EY, Joslin CE, Sugar J, Booton GC, Shoff ME, Fuerst PA, et al. The relative value of confocal microscopy and superficial corneal scrapings in the diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea. 2008;27:764–72. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31816f27bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kobayashi A, Ishibashi Y, Oikawa Y, Yokogawa H, Sugiyama K. In vivo and ex vivo laser confocal microscopy findings in patients with early-stage Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea. 2008;27:439–45. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318163cc77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alomar T, Matthew M, Donald F, Maharajan S, Dua HS. In vivo confocal microscopy in the diagnosis and management of Acanthamoeba keratitis showing new cystic forms. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;37:737–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2009.02128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaufman SC, Musch DC, Belin MW, Cohen EJ, Meisler DM, Reinhart WJ, et al. Confocal microscopy: A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:396–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hau SC, Dart JK, Vesaluoma M, Parmar DN, Claerhout I, Bibi K, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of microbial keratitis within vivo scanning laser confocal microscopy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:982–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.175083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elder MJ, Kilvington S, Dart JK. A clinicopathologic study ofin vitro sensitivity testing and Acanthamoeba keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:1059–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schuster FL, Visvesvara GS. Opportunistic amoebae: Challenges in prophylaxis and treatment. Drug Resist Updat. 2004;7:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duguid IG, Dart JK, Morlet N, Allan BD, Matheson M, Ficker L, et al. Outcome of Acanthamoeba keratitis treated with polyhexamethyl biguanide and propamidine. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:1587–92. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Larkin DF, Kilvington S, Dart JK. Treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis with polyhexamethylene biguanide. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:185–91. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31994-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seal D, Hay J, Kirkness C, Morrell A, Booth A, Tullo A, et al. Successful medical therapy of Acanthamoeba keratitis with topical chlorhexidine and propamidine. Eye (Lond) 1996;10(Pt 4):413–21. doi: 10.1038/eye.1996.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Azuara-Blanco A, Sadiq AS, Hussain M, Lloyd JH, Dua HS. Successful medical treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Int Ophthalmol. 1997;21:223–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1006055918101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lim N, Goh D, Bunce C, Xing W, Fraenkel G, Poole TR, et al. Comparison of polyhexamethylene biguanide and chlorhexidine as monotherapy agents in the treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:130–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mathers W. Use of higher medication concentrations in the treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:923. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.6.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakagawa H, Hattori T, Koike N, Ehara T, Fujita K, Takahashi H, et al. Investigation of the role of bacteria in the development of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea. 2015;34:1308–15. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sharma R, Jhanji V, Satpathy G, Sharma N, Khokhar S, Agarwal T, et al. Coinfection with Acanthamoeba and pseudomonas in contact lens-associated keratitis. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90:e53–5. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31827f15b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lambrecht E, Baré J, Chavatte N, Bert W, Sabbe K, Houf K, et al. Protozoan cysts act as a survival niche and protective shelter for foodborne pathogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:5604–12. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01031-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tu EY, Joslin CE, Shoff ME. Successful treatment of chronic stromal Acanthamoeba keratitis with oral voriconazole monotherapy. Cornea. 2010;29:1066–8. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181cbfa2c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Park DH, Palay DA, Daya SM, Stulting RD, Krachmer JH, Holland EJ, et al. The role of topical corticosteroids in the management of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea. 1997;16:277–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rahimi F, Hashemian SM, Tafti MF, Mehjerdi MZ, Safizadeh MS, Pour EK, et al. Chlorhexidine monotherapy with adjunctive topical corticosteroids for Acanthamoeba keratitis. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2015;10:106–11. doi: 10.4103/2008-322X.163782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carnt N, Robaei D, Watson SL, Minassian DC, Dart JK. The impact of topical corticosteroids used in conjunction with antiamoebic therapy on the outcome of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:984–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.John T, Lin J, Sahm D, Rockey JH. Effects of corticosteroids in experimental Acanthamoeba keratitis. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(Suppl 5):S440–2. doi: 10.1093/clind/13.supplement_5.s440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kashiwabuchi RT, de Freitas D, Alvarenga LS, Vieira L, Contarini P, Sato E, et al. Corneal graft survival after therapeutic keratoplasty for Acanthamoeba keratitis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86:666–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ficker LA, Kirkness C, Wright P. Prognosis for keratoplasty in Acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:105–10. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31707-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kitzmann AS, Goins KM, Sutphin JE, Wagoner MD. Keratoplasty for treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:864–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Robaei D, Carnt N, Minassian DC, Dart JK. Therapeutic and optical keratoplasty in the management of Acanthamoeba keratitis: Risk factors, outcomes, and summary of the literature. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Anshu A, Parthasarathy A, Mehta JS, Htoon HM, Tan DT. Outcomes of therapeutic deep lamellar keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty for advanced infectious keratitis: A comparative study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:615–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sarnicola E, Sarnicola C, Sabatino F, Tosi GM, Perri P, Sarnicola V, et al. Early deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK) for Acanthamoeba keratitis poorly responsive to medical treatment. Cornea. 2016;35:1–5. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Herz NL, Matoba AY, Wilhelmus KR. Rapidly progressive cataract and iris atrophy during treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:866–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Awwad ST, Heilman M, Hogan RN, Parmar DN, Petroll WM, McCulley JP, et al. Severe reactive ischemic posterior segment inflammation in Acanthamoeba keratitis: A new potentially blinding syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:313–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee GA, Gray TB, Dart JK, Pavesio CE, Ficker LA, Larkin DF, et al. Acanthamoeba sclerokeratitis: Treatment with systemic immunosuppression. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1178–82. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iovieno A, Gore DM, Carnt N, Dart JK. Acanthamoeba sclerokeratitis: Epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:2340–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Arnalich-Montiel F, Jaumandreu L, Leal M, Valladares B, Lorenzo-Morales J. Scleral and intraocular amoebic dissemination in Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea. 2013;32:1625–7. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31829ded51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moshari A, McLean IW, Dodds MT, Damiano RE, McEvoy PL. Chorioretinitis after keratitis caused by Acanthamoeba: Case report and review of the literature. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:2232–6. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00765-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Robaei D, Carnt N, Minassian DC, Dart JK. The impact of topical corticosteroid use before diagnosis on the outcome of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1383–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Claerhout I, Goegebuer A, Van Den Broecke C, Kestelyn P. Delay in diagnosis and outcome of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:648–53. doi: 10.1007/s00417-003-0805-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bacon AS, Dart JK, Ficker LA, Matheson MM, Wright P. Acanthamoeba keratitis. The value of early diagnosis. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:1238–43. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31499-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tu EY, Joslin CE, Sugar J, Shoff ME, Booton GC. Prognostic factors affecting visual outcome in Acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1998–2003. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]