Abstract

Background and aims

There is a well-established association between pathological gambling and substance use disorders in adolescents. The aim of this study was to shed light on the association between adolescents’ different levels of involvement in gambling activities and substance use (smoking tobacco and cannabis and drinking alcoholic beverages), based on a large sample.

Methods

A survey was conducted in 2013 on 34,746 students attending 619 secondary schools, who formed a representative sample of the Italian 15- to 19-year-old population. The prevalence of different categories of gamblers was estimated by age group and gender. A multiple correspondence analysis (CA) was conducted to explain the multivariate associations between substance use and gambling.

Results

The prevalence of problem gambling was 2.7% among the 15- to 17-year-olds, and rose to 3.6% among the 18- and 19-year-olds. Multiple CA revealed that, even when it does not reach risk-related or problem levels, gambling is associated with the use of alcohol and tobacco. In particular, the analysis showed that non-problem gambling levels were associated with alcohol and tobacco use at least once in the previous month, and that higher-risk gambling levels related to the use of cannabis and episodes of drunkenness at least once in the previous month.

Conclusion

This study found that any gambling behavior, even below risk-related or problem levels, was associated with some degree of substance use by youths, and that adolescents’ levels of gambling lay along a continuum of the categories of substance use.

Keywords: gambling, adolescent, substance use, drinking, smoking

Introduction

Alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis are the three substances most commonly used by youth, and their misuse poses a major public health problem (Barnes, Welte, Hoffman, & Tidwell, 2009). It is common knowledge that adolescents tend to be impulsive, and this is an age when they are most likely to experiment with alcohol, tobacco, and drugs, and possibly become regular users of these substances. Epidemiological data show that the prevalence of “heavy episodic drinking” among adolescents has remained unchanged over the past 20 years (Kraus et al., 2016). The same report indicated that almost one in five (21%) 15- to 19-year-old students could be defined as regular smokers, 13% reported having been drunk on alcohol in the previous month, and 16% reported having used cannabis at least once in their lifetime. The Italian Department for Drug Prevention Policies found that one in four 14- to 19-year-old students had consumed an illicit drug in 2014, and this was cannabis in 76.5% of cases (Dipartimento delle Politiche Antidroga, 2014).

Longitudinal studies have also confirmed that adolescence is a time of life when individuals are more inclined to explore new stimuli and to engage in gambling (Goudriaan, Slutske, Krull, & Sher, 2009). The severity of gambling-related problems has been divided into three categories (non-problem gambling, at-risk gambling, and problem gambling) based on a broad criterion that combines gambling frequency with South Oaks Gambling Screen – Revised for Adolescents (SOGS-RA) scores (Winters, Stinchfield, & Fulkerson, 1993, modified by Poulin, 2002). Gambling activities can be classified as belonging to three basic formats, based on style of play: lotteries, wagers, and gaming. The most common forms of gambling practiced by adolescents in Italy are scratch cards, instant lotteries, and betting on sporting events (Kraus et al., 2016). International studies have consistently shown that gambling is one of the life experiences of most young people, and their first encounter with gambling can occur at a very early age. Today’s youth have grown up in a time characterized by an abundance of gambling opportunities (Volberg, Gupta, Griffiths, Olason, & Delfabbro, 2010). Young people approach gambling for very innocent reasons, often with the endorsement of their parents and families. The readily available scratch-and-win card is the form of gambling most often used by young adolescents (Gallimberti et al., 2016), but afternoon poker games, betting on sporting events, and participation in sweepstakes and 50–50 draws also enjoy a social “stamp of approval” (Gupta & Derevensky, 1997). As in the case of alcohol and drugs, adolescents see people they respect engage in such activities, and consequently assume they must be acceptable. This makes them more likely to take up a gambling opportunity if given the chance (Griffiths, 2003). It is against the law for individuals under the age of 18 to engage in most legal forms of gambling, but it is easy to find adults willing to help or let them gamble, so the legal restriction is no obstacle to their experimenting with such activities (Gupta & Derevensky, 1997). Technology has generated new ways to gamble using Internet, mobile phones, and interactive television (Griffiths & Parke, 2010), and it has been argued that young people are particularly receptive to such modern forms of gambling because of the apparent similarity between these and other technology-based games with which they are already familiar (Delfabbro, King, Lambos, & Puglies, 2009).

Alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and illicit substance use are types of behavior that are associated with each other and with problem gambling (Barnes, Welte, Hoffman, & Dintcheff, 1999). Substance use and gambling share a temporal link in their incipit in adolescence, but recent evidence has shown that they are also related in their “etiopathogenesis.” Adolescence is a developmental stage in which impulsive behavior is more common (Clayton, 1992), and this impulsiveness is seen as an important factor linking gambling with substance use in this age group (Ellenbogen, Derevensky, & Gupta, 2007). Several studies identified a strong co-occurrence of gambling and substance use disorders in young people from 9 to 21 years old (Barnes, Welte, Hoffman, & Tidwell, 2011; Peters et al., 2015). Excessive and problem gambling were found significantly related to heavy drinking, tobacco and marijuana smoking, and problems or symptoms associated with the use of these three substances (Barnes et al., 2009; Blinn-Pike, Worthy, & Jonkman, 2010). None of these studies considered the association between gambling on a level not defined as “risky” and the use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana in adolescents. The aim of this study was to clarify the association between different levels of gambling activity and substance use.

Methods

Materials

Our sample population was drawn from the SPS-DAP Student Population Survey conducted by the Department for Drug Prevention Policies in Italy during the first half of 2013, in collaboration with the Ministry of Education, Universities and Research, and with the participation of the Regional Representatives for Health Education. Full details of the design of the SPS-DAP have been published elsewhere (Presidenza del Consiglio Dei Ministri – Dipartimento Politiche Antidroga, 2013). For the purposes of this study, the survey is briefly described below.

Sample

The sample refers to the Italian student population between 15 and 19 years of age, sampled using a two-stage procedure that selected first a set of secondary schools, and then a set of students attending the schools concerned. The units (schools) selected in the first stage were stratified by region and type of school. The statistical units for the survey were represented by all the students attending each of the classes forming part of the sample, selected using a clustering method. The survey was conducted using a Computer-Aided Self-Completed Interview method that enabled the questionnaire to be completed by students online using a non-replicable, unique, and anonymous access ID. A total of 478 schools participated in the survey (77.2% of all the schools selected), accounting for a total student population of 39,643. The questionnaires collected were examined to exclude any unreliable or irrelevant responses: 3,171 questionnaires were rejected because they were answered by students outside the age group considered in the survey (15- to 19-year-olds); another 1,415 were rejected because respondents had not completed the sections on gambling or psychotropic substance use; and a further 311 because they contained answers that were judged scarcely plausible. Thus, a total of 34,746 questionnaires were considered eligible for this study.

Variables

The following variables were considered in the analysis: tobacco smoking (S), alcohol drinking (A), episodes of drunkenness (D), and use of cannabis (C). Each variable was classified according to respondents’ self-reported usage in one of the four categories:

-

1.

“no,” i.e., the student reported never having used the corresponding substance;

-

2.

“former user, at least once in a lifetime” (LT), i.e., the respondent had at least one past experience (of any amount), but not in the previous year;

-

3.

“former user, at least last year” (LY), i.e., the adolescent had at least one experience (of any amount) in the previous year, but not in the previous month; and

-

4.

“current user, at least last month” (LM), i.e., the substance had been used at least once (in any amount) in the previous 30 days.

The SOGS-RA (Poulin, 2002; Winters et al., 1993) was used to examine respondents’ gambling behavior. This validated instrument includes 12 items (scores range from 0 to 12) measuring several aspects, such as loss of control over the game, action taken to recover monetary losses, interference with family, school, and relational life, guilt feelings about the money spent, and consequences of gambling. To be defined as gamblers, respondents had to report having been involved in a gambling activity at least once in the previous year. The SOGS-RA scale identifies three types of gambler: non-problem (SOGS-RA score = 0–1); at risk (SOGS-RA = 2–3); and problem (SOGS-RA score higher than 4). Students who reported having no experience of gambling in the previous year were defined as “not gamblers.”

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for the students’ main demographic characteristics. The prevalence (and confidence interval) of each type of gambler was estimated by gender and age group. A set of Pearson’s chi-square (χ2) tests was used to highlight any associations between gambling and the use of tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis.

Finally, multiple correspondence analysis (CA) (a multidimensional technique) was used to summarize the relationships between all the variables involved and detect the underlying structure of the data. This approach enables the data to be represented graphically in a low-dimensional Euclidean space (Greenacre, 1984; Hirschfeld, 1935). The graphical display of the relationships offers a user-friendly overview of the salient relationships between categories of variables that are not easily captured by looking at contingency tables. Inertia is a measure of the variance or dispersion of individual profiles around an average profile, representing a measure of the deviation from independence (Sourial et al., 2010). The measure of association used in CA is the χ2 distance between the response categories. The mathematical form of this measure helps to ensure that larger observed proportions do not dominate the calculation of the distance relative to smaller proportions. CA thus provides a more precise measure of association than other multivariate techniques based on the correlation coefficient, for which no such standardization is performed (Sourial et al., 2010). CA breaks down the inertia by identifying a small number of mutually independent dimensions representing the most important deviations from independence (Sourial et al., 2010). Dimensions are formed by identifying the axes for which the distance between the profiles and the axes is minimized, whereas the amount of inertia explained is maximized. Each dimension has an eigenvalue that represents its relative importance and how much of the inertia it explains. For the purposes of our analysis, the variables were represented in a two-dimensional space, and proximity between the usage modalities of two variables meant that the variables were associated (e.g., LM-drunkenness and LM-cannabis), whereas proximity between levels of the same gambling risk variable (e.g., SOGS-RA 1 and SOGS-RA 2) meant that the sets of observations associated with these two risk levels were similar. Three models were obtained:

-

–

Model 1 displays only the variables regarding the use of tobacco, alcohol and cannabis (categorized as never, LT, LY, and LM).

-

–

Model 2 adds to Model 1, displaying gambling in disaggregate form (not gamblers and SOGS-RA scores from 0 to 12).

-

–

Model 3 adds to Model 1, displaying gambling categories (not gambler, non-problem, at risk, and problem).

Ethical issues

The data analysis was performed on anonymized and aggregated data with no chance of individuals being identifiable. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and with Italian Law no. 196/2003 on the protection of personal data. The recent resolution no. 85/2012 of the Italian Guarantor for the Protection of Personal Data also confirmed that it is allowable to process personal data for medical, biomedical, and epidemiological research, and that data concerning health status may be used in aggregate form in scientific studies. Participants’ parents were informed by the school director about the aims of this study, and gave their consent when they approved the school’s annual education plan.

Results

Table 1 provides details of the study sample, which comprised a total of 34,746 students from 15 to 19 years old [mean age = 17 years (SD = 1.38)]. About one in three of them had smoked in the last month, whereas 40.4% had never smoked; more than half of the sample reported drinking alcohol in the last month, and nearly 15% had been drunk; and 15.0% of the sample had smoked marijuana at least once in the 30 days preceding the survey.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample (n = 34,745)

| % (N) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 50.2 (17,436) |

| Age | |

| Mean age (M ± SD) | 17.0 (±1.38) |

| Smokers | |

| Never smoked | 40.4 (14,053) |

| Former smokers LT | 11.8 (4,110) |

| Former smokers LY | 10.6 (3,677) |

| Current smokers | 37.1 (12,906) |

| Alcohol drinkers | |

| Never drank alcohol | 15.5 (5,400) |

| Former drinkers LT | 8.1 (2,823) |

| Former drinkers LY | 17.9 (6,213) |

| Current drinkers | 58.5 (20,310) |

| Drunkenness | |

| Never been drunk | 56.4 (19,596) |

| Former drunken episode(s) LT | 10.1 (3,509) |

| Former drunken episode(s) LY | 17.8 (6,181) |

| Current drunken episode(s) | 15.7 (5,460) |

| Cannabis smokers | |

| Never smoked cannabis | 75.7 (26,310) |

| Former cannabis smokers LT | 2.9 (1,024) |

| Former cannabis smokers LY | 6.3 (2,190) |

| Current cannabis smokers | 15.0 (5,222) |

| Gamblers | |

| Never gambled | 51.8 (18,010) |

| SOGS-RA score of 0 | 35.2 (12,245) |

| SOGS-RA score of 1 | 5.8 (2,002) |

| SOGS-RA score of 2 | 2.7 (921) |

| SOGS-RA score of 3 | 1.5 (508) |

| SOGS-RA score of 4 | 1.0 (349) |

| SOGS-RA score of 5 | 0.6 (215) |

| SOGS-RA score of 6 | 0.4 (150) |

| SOGS-RA score of 7 | 0.3 (102) |

| SOGS-RA score of 8 | 0.2 (65) |

| SOGS-RA score of 9 | 0.1 (34) |

| SOGS-RA score of 10 | 0.1 (30) |

| SOGS-RA score of 11 | 0.2 (75) |

| SOGS-RA score of 12 | 0.1 (40) |

Note. M: mean; SD: standard deviation; LT: lifetime; LY: at least 1 in the last year; SOGS-RA: South Oaks Gambling Screen – Revised for Adolescents.

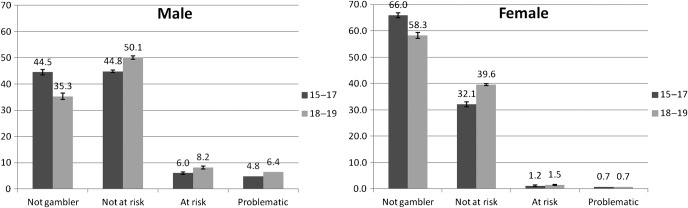

As for gambling, 48.2% (47.7–48.7) had experience of gambling in the previous year: they were classified as non-problem gamblers in 41.0% (40.5–41.5) of cases; at risk in 4.1% (3.9–4.3); and problem gamblers in 3.1% (2.9–3.3). Figure 1 shows that gambling is more prevalent among males than among females, and that there were students under 18 years old among the gamblers, although it is against the law. As expected, involvement in gambling increased with age, and this was particularly evident in the share of male respondents classified as being at risk (6% of students aged 15–17 as opposed to 8.2% of those aged 18–19) and problem gamblers (4.8% and 6.4%, respectively).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of gambling risk category by age group and sex

Table 2 contains the results of the bivariate analysis on gambling and substance use. Gambling was found associated with all the types of substance use considered. More than half of the problem gamblers had smoked and 81% had drunk alcohol at least once in the previous month.

Table 2.

Bivariate analysis of gambling and cigarette and/or marijuana smoking, alcohol drinking, and drunken episodes

| SOGS-RA | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not gambler, % (N) | Non-problem gambler, % (N) | At-risk gambler, % (N) | Problem gambler, % (N) | ||

| Never smoked | 45.5 (8,201) | 36.5 (5,202) | 27.9 (399) | 23.7 (251) | <.001 |

| Former smokers LT | 11.5 (2,064) | 12.3 (1,750) | 12.3 (176) | 11.3 (120) | |

| Former smokers LY | 9.9 (1,779) | 11.2 (1,602) | 12.5 (179) | 11.0 (117) | |

| Current smokers | 33.1 (5,966) | 40.0 (5,693) | 47.2 (675) | 54.0 (572) | |

| Never drank alcohol | 21.0 (3,777) | 10.2 (1,455) | 6.7 (96) | 6.8 (72) | <.001 |

| Former drinkers LT | 9.5 (1,714) | 7.0 (1,002) | 4.8 (68) | 3.7 (39) | |

| Former drinkers LY | 18.7 (3,368) | 17.9 (2,551) | 14.2 (203) | 8.6 (91) | |

| Current drinkers | 50.8 (9,151) | 64.8 (9,239) | 74.3 (1,062) | 80.9 (858) | |

| Never been drunk | 62.6 (11,269) | 52.0 (7,415) | 40.1 (573) | 32.0 (339) | <.001 |

| Former drunken episode(s) LT | 9.5 (1,713) | 10.6 (1,508) | 12.1 (173) | 10.8 (115) | |

| Former drunken episode(s) LY | 15.3 (2,752) | 19.8 (2,820) | 24.8 (355) | 24.0 (254) | |

| Current drunken episode(s) | 12.6 (2,276) | 17.6 (2,504) | 23.0 (328) | 33.2 (352) | |

| Never smoked cannabis | 80.3 (14,458) | 72.7 (10,354) | 63.4 (906) | 55.8 (592) | <.001 |

| Former cannabis smokers LT | 2.7 (482) | 3.1 (445) | 3.8 (55) | 4.0 (42) | |

| Former cannabis smokers LY | 5.2 (939) | 7.3 (1,039) | 9.4 (135) | 7.3 (77) | |

| Current cannabis smokers | 11.8 (2,131) | 16.9 (2,409) | 23.3 (333) | 32.9 (349) | |

Note. LT: lifetime; LY: at least 1 in the last year; SOGS-RA: South Oaks Gambling Screen – Revised for Adolescents.

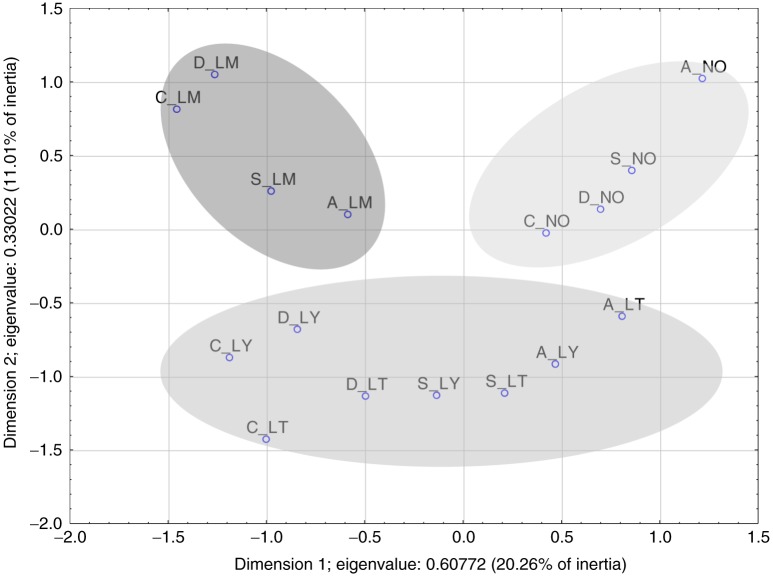

Figure 2 shows the projections for the categories of each variable on the first two dimensions resulting from the first model, which only considers substance use. Dimension 1 accounts for 20.3% of the variance in the data, and Dimension 2 for 11.0% of the variance. If we analyze the contributions to the inertia of the categories of variables better represented on the first axis, then – reading the graph from left to right – we first encounter current cannabis users and students with frequent episodes of drunkenness, followed by current users of tobacco or alcoholic beverages, whereas adolescents who have never smoked or drunk alcohol are at the opposite end of the axis. The first dimension could therefore represent the risk related to the experience associated with each addiction behavior. As for the second axis, the contributions to the inertia of the categories of variables, and their position relative to the origin of the axis, show a clear contrast between the “LY”/“LT” and the “LM”/“NO” modalities. The second dimension could therefore represent intentionality: what links students who have never experimented with any of the risk-taking behaviors considered with those who have done so more than once is their resolute and persevering attitude to the transgressive experiences of adolescence.

Figure 2.

Model 1: two-dimensional projections of substance use variables. A: alcohol drinking; S: smoking; C: cannabis smoking; D: being drunk; LT: in lifetime; LY: in last year; LM: in last month

This analysis also seems to identify three distinct groups of adolescents. One, located in the upper left-hand corner, includes the teenage students at greatest risk, who had drunk alcoholic beverages, smoked cigarettes and cannabis, and been drunk at least once in the previous month. In the upper right-hand corner, there are the students who had never smoked cigarettes or cannabis, and never drunk any alcoholic beverages. The third group occupies the lower part of the graph, representing students who had experimented with the types of behavior explored at least once in their life or in the previous year.

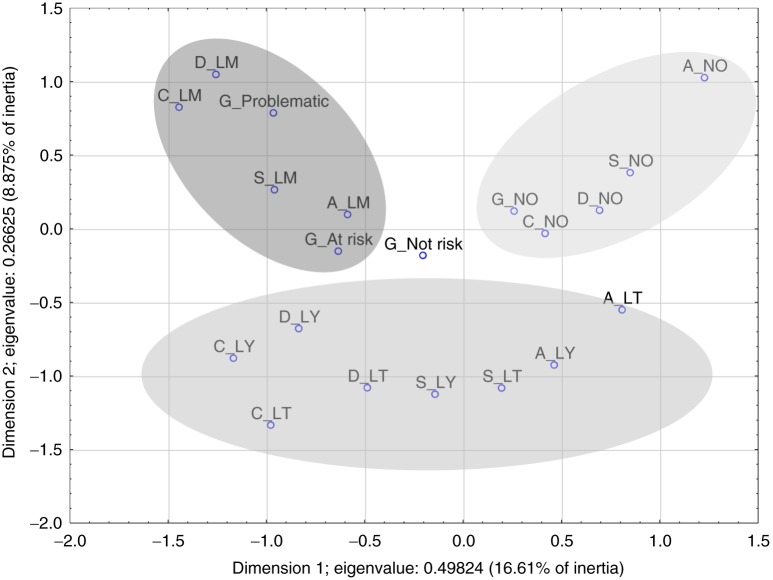

Figure 3 (x = 16.6%, y = 8.9%) was obtained by pooling the SOGS-RA scores into three categories, as explained earlier, and it reveals three clusters of the categories for each variable that correspond to three different attitudes to the risk-taking behavior in question. The first cluster comprises the students who were “not interested”: they had never tried drinking alcoholic beverages or smoking, and they had no experience of gambling in the previous year. The second cluster might be described as the “experimenters,” adolescents who had tried alcohol, cigarettes, and cannabis at least once in their life, or in the last year, but who were not classified as current users. The third cluster coincides with the “problem” category of teenage students, who were current smokers and alcohol consumers, and who had smoked cannabis and been drunk at least once in the previous 30 days. This group revealed a vertical gradient coinciding with all kinds of non-problem, at risk, and problem gambling.

Figure 3.

Model 2: adding to Model 1, it shows gambling by pooled scoring categories (not gambler, non-problem gambler, at-risk gambler, and problem gambler). A: alcohol drinking; S: smoking; C: cannabis smoking; D: being drunk; G: gambling; LT: in lifetime; LY: in last year; LM: in last month

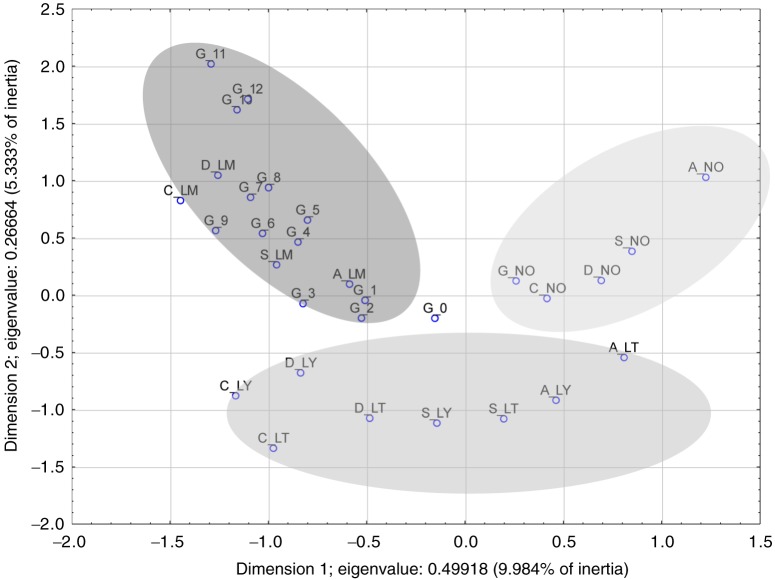

Figure 4 (x = 10.0%, y = 5.3%) shows the two-dimensional projections of the model after adding the gambling variable, and classifying the sample as either “not gamblers” or students scoring from 0 to 12, depending on their involvement in gambling activities. As with the previous model, analyzing these results seems to confirm the distinction between the same three groups. Adolescents with no experience of any gambling behavior in the previous 12 months occupied the same portion of the graph as those who had never tried cannabis and never been drunk. Starting from 0, the SOGS-RA scores were distributed along a severity gradient that rose toward the group at greatest risk, i.e., from the center to the upper left-hand corner of the graph. The axes can be interpreted in the same way as for the previous model.

Figure 4.

Model 3: adding to Model 1, it shows gambling in disaggregate form [not gamblers and gamblers with a SOGS-RA scores (G_0–G_12)]. A: alcohol drinking; S: smoking; C: cannabis smoking; D: being drunk; G: gambling; LT: in lifetime; LY: in last year; LM: in last month

Discussion

This study demonstrates that gambling, even below risk-related or problem levels, was associated with substance use by youths at least in the previous month, and that adolescents’ gambling levels lay along a continuum of the categories of substance use.

A recent meta-analysis estimated the proportion of probable pathological gamblers among college students at 10.2%. Recent studies have also indicated that, despite adolescent gambling being illegal, youths engage in gambling with a higher prevalence rate than adults (Volberg et al., 2010). In this study on a population of high-school age, the proportion of problem gamblers was low (just under 3%), but nearly half of the teenagers reported having been involved in some form of gambling during the previous year (Nowak & Aloe, 2014). Focusing on the trend in Italy, the latest Italian ESPAD reports (2009–2015) show that the proportion of adolescents who had engaged in gambling in the previous 12 months was about 47% in the years 2009–2011, then dropped to 39% up until 2014 (ESPAD Italy, 2014), before rising again in recent years (41.7% in 2015). According to a recent review on adolescent gambling, the greater availability of legal gambling opportunities seems to lead to an increase in the prevalence and in the onset of gambling problems among young people (Calado, Alexandre, & Griffiths, 2017). Several studies have also demonstrated that, given the opportunity, most adolescents will gamble to some degree, especially if they have developed the general impression that gambling is acceptable and normal (Wilber & Potenza, 2006). Risk-taking is also a typical feature of adolescence (Jessor, 1992), making this age group more vulnerable than adults to the appeal of gambling (Shaffer & Hall, 1996). Despite legal age restrictions, adolescents can easily access lawful gambling opportunities, such as electronic gambling machines in bars and restaurants, and products such as instant scratch cards and sports-themed lotteries (Derevensky & Gupta, 2001; Gupta & Derevensky, 1998). Self-organized gambling activities such as card games, dice games, and sports pools are common among youth, but online gambling represents the fastest-growing segment of non-legalized gambling activities (Griffiths, Parke, & Derevensky, 2011). Internet gambling sites are not only readily accessible, convenient, and anonymous, but they also provide an alternative reality and an immediate gratification that appeal to adolescents (Griffiths & Barnes, 2008). Online gambling is one of the major concerns because it has been demonstrated that adolescent problem gambling rates were five times higher among online gamblers than among other gamblers (Canale, Griffiths, Vieno, Siciliano, & Molinaro, 2016).

Based on the hypothesis of a link between problem gambling and the vulnerability to loss of control typical of adolescence (Chambers & Potenza, 2003), previous studies found that pathological gambling was often associated with high comorbidity rates for alcohol-related disorders and nicotine dependence, suggesting that each of these types of behavior may serve as a primer for the others (McGrath & Barrett, 2009; Peters et al., 2015). Previous research thus focused on the relationship between problem gambling and other risk-related behaviors, showing that problem gamblers are greater risk-takers, and that adolescent problem gamblers are at higher risk of acquiring other addictions and becoming involved in delinquent activities.

Our findings in Italian adolescents on the association between substance use and gambling prove that even moderate experiences of so-called “non-problem” gambling are associated with the ongoing consumption (at least in the previous month) of alcohol and cigarettes. Going into detail, students who avoided using any substances also avoided gambling. Low levels of gambling, commonly considered as “non-problem gambling,” were associated with the use of tobacco and alcohol at least once in the previous month, whereas “problem” gambling was associated with the use of cannabis or drunkenness at least once in the previous month. Not current substance use does not seem to be associated with any specific gambling level, however. The SOGS-RA scores measuring adolescents’ involvement in gambling were distributed along a straight line that also represented their substance use. Alcohol and tobacco were at the lower end of the line, cannabis and drunkenness at the higher end. These results show that any amount of gambling, even when it is not considered at “problem” level, is associated with substance use in adolescents. Such findings are particularly important because it has been demonstrated in the literature that adolescents can move quickly from non-problem to problem gambling (Gupta & Derevensky, 2000), and relatively few adolescents seek help for gambling problems.

Lesieur et al. (1991) made the point that it is hard to say whether these various forms of inappropriate adolescent behavior follow one another in a particular sequence, develop at the same time, or are causally connected in some way. They nonetheless noted that “gambling, getting drunk, and illegal drug abuse are indicators of a global pattern of risk-taking and antisocial behavior.” For decades, social theorists have posited that various types of problem behavior, such as substance abuse and other forms of risk-taking may co-exist in adolescents, constituting what Jessor and Jessor (1977a) termed a problem behavior syndrome. Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) explained this connection as being due to the fact that adolescents find these types of behavior easily and immediately gratifying, while they have no concern for any long-range consequences. Gambling fits this bill too, as it provides an instant pleasure. This interpretation is supported by the shared underlying risk factors (Jessor & Jessor, 1997b). Since adolescence is considered a developmental phase in which impulsive behavior is more likely (Clayton, 1992), impulsiveness – as manifested by the inability to stop or inhibit a behavior regardless of its consequences, the tendency to act without anticipating the consequences of the action, excessive sensitivity to immediate reinforcement, and a relative insensitivity to punishment (Vitaro, Brendgen, Ladouceur, & Tremblay, 2001) – may be an important common denominator linking gambling with illicit substance abuse in adolescence (Ellenbogen et al., 2007).

It may be that the use of certain substances prompts a stronger tendency to gamble because it decreases the user’s vigilance and inhibitory mechanisms or maybe drinking alcohol or taking drugs makes individuals less concerned about spending their money on gambling, and thus more likely to become problem gamblers. Another possibility is that drug or alcohol users need money and they use gambling as a means to procure it (Vitaro et al., 2001). The directionality of the relationship between alcohol use, illicit substance abuse, and gambling behavior nonetheless remains debatable.

This study has several limitations, primarily relating to the fact that our data were obtained from a sample of adolescents attending school, which means that those who dropped out of school at 16 years old (on completing their compulsory education in Italy) – who might be at greater risk of substance use disorders – were not considered, so our sample was only representative of Italian school students. A second limitation lies, as with other national prevalence studies, in that the findings are based on self-reports and may consequently underestimate substance use. On the other hand, assuring respondents’ anonymity and confidentiality, and administering the survey in a controlled environment enhance the likelihood of obtaining accurate information (Winters, Stinchfield, Henly, & Schwartz, 1991). Third, the cross-sectional design of this study prevented us from identifying any cause–effect relationships between the variables, though the consistency of our findings with those of other studies on the associations considered should suffice to support the development of a greater public health awareness of the need to prevent any involvement of adolescents in gambling. Finally, the analysis did not use a complex survey approach; given the large sample size, the Bernoulli’s simple random sampling approach was adopted.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that any gambling behavior, however minimal, correlates with ongoing substance use in young people. It also shows that adolescents’ “level of gambling risk” lies along a continuum, and even low levels of gambling are associated with alcohol and tobacco use in adolescents.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments that greatly contributed to improving the final version of the paper.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: This study was sponsored and financed by the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, realized from EXPLORA Center Associate of the University Consortium of Industrial and Managerial Economics (CUEIM), custodial institution for the survey year.

Authors’ contribution

PV obtained funding, coordinated all study phases, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. MS and MS carried out the statistical analyses, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. BG obtained funding and designed the data collection instruments, coordinated and supervised data collection. CL wrote the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. FV and ES conceptualized the study and involved in data collection. AB reviewed and revised the manuscript, data interpretation, critically reviewed, and revised the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article.

References

- Barnes G. M., Welte J. W., Hoffman J. H., Dintcheff B. A. (1999). Gambling and alcohol use among youth: Influences of demographic, socialization, and individual factors. Addictive Behaviors, 24(6), 749–767. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(99)00048-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G. M., Welte J. W., Hoffman J. H., Tidwell M. C. O. (2009). Gambling, alcohol, and other substance use among youth in the United States. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70(1), 134–142. doi:10.15288/jsad.2009.70.134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G. M., Welte J. W., Hoffman J. H., Tidwell M. C. O. (2011). The co‐occurrence of gambling with substance use and conduct disorder among youth in the United States. The American Journal on Addictions, 20(2), 166–173. doi:10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00116.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blinn-Pike L., Worthy S. L., Jonkman J. N. (2010). Adolescent gambling: A review of an emerging field of research. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47(3), 223–236. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calado F., Alexandre J., Griffiths M. D. (2017). Prevalence of adolescent problem gambling: A systematic review of recent research. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(2), 397–424. doi:10.1007/s10899-016-9627-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canale N., Griffiths M. D., Vieno A., Siciliano V., Molinaro S. (2016). Impact of Internet gambling on problem gambling among adolescents in Italy: Findings from a large-scale nationally representative survey. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 99–106. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.020 [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R. A., Potenza M. N. (2003). Neurodevelopment, impulsivity, and adolescent gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 19(1), 53–84. doi:10.1023/A:1021275130071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton R. R. (1992). Transitions in drug use: Risk and protective factors. In Glantz M., Pickens R. (Eds.), Vulnerability to drug abuse (pp. 15–51). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Delfabbro P., King D., Lambos C., Puglies S. (2009). Is video-game playing a risk factor for pathological gambling in Australian adolescents? Journal of Gambling Studies, 25(3), 391–405. doi:10.1007/s10899-009-9138-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derevensky J. L., Gupta R. (2001). Lottery ticket purchases by adolescents: A qualitative and quantitative examination. Report prepared for the Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- Dipartimento delle Politiche Antidroga. (2014). Relazione annuale al Parlamento 2014. Uso di sostanze stupefacenti e tossicodipendenze in Italia [Annual Report to Parliament 2014. Use of drugs and addictions in Italy]. Retrieved from http://www.politicheantidroga.gov.it/media/646882/relazione%20annuale%20al%20parlamento%202014.pdf (October 10, 2016).

- Ellenbogen S., Derevensky J., Gupta R. (2007). Gender differences among adolescents with gambling-related problems. Journal of Gambling Studies, 23(2), 133–143. doi:10.1007/s10899-006-9048-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESPAD Italy. (2014). Tables. Retrieved from https://www.epid.ifc.cnr.it/AreaDownload/Report/ESPAD/standard_table02/Standard_Table02_2014.pdf (October 10, 2016).

- Gallimberti L., Buja A., Chindamo S., Terraneo A., Marini E., Perez L. J. G., Baldo V. (2016). Experience with gambling in late childhood and early adolescence: Implications for substance experimentation behavior. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 37(2), 148–156. doi:10.1097/DBP.0000000000000252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson M. R., Hirschi T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goudriaan A. E., Slutske W. S., Krull J. L., Sher K. J. (2009). Longitudinal patterns of gambling activities and associated risk factors in college students. Addiction, 104(7), 1219–1232. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02573.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenacre M. J. (1984). Theory and applications of correspondence analysis. London, UK: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. D. (2003). Internet gambling: Issues, concerns, and recommendations. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 6(6), 557–568. doi:10.1089/109493103322725333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. D., Barnes A. (2008). Internet gambling: An online empirical study among student gamblers. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 6(2), 194–204. doi:10.1007/s11469-007-9083-7 [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. D., Parke J. (2010). Adolescent gambling on the Internet: A review. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 22, 59–75. doi:10.1007/s11469-011-9318-5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. D., Parke J., Derevensky J. L. (2011). Remote gambling in adolescence. In Derevensky J. L., Shek D. T. L., Merrick J. (Eds.), Youth gambling: The hidden addiction (pp. 125–142). Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R., Derevensky J. L. (1997). Familial and social influences on juvenile gambling behavior. Journal of Gambling Studies, 13(3), 179–192. doi:10.1023/A:1024915231379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R., Derevensky J. L. (1998). Adolescent gambling behavior: A prevalence study and examination of the correlates associated with problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 14(4), 319–345. doi:10.1023/A:1023068925328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R., Derevensky J. L. (2000). Adolescents with gambling problems: From research to treatment. Journal of Gambling Studies, 16, 315–342. doi:10.1023/A:1009493200768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld H. (1935). A connection between correlation and contingency. Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 31(4), 520–524. doi:10.1017/S0305004100013517 [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. (1992). Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Developmental Review, 12(4), 374–390. doi:10.1016/0273-2297(92)90014-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R., Jessor S. L. (1977a). Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R., Jessor S. L. (1977b). Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus L., Guttormsson U., Leifman H., Arpa S., Molinaro S., Monshouwer K., Trapencieris M., Vicente J., Arnarsson A. M., Balakireva O., Bye E. K., Chileva A., Ciocanu M., Clancy L., Csémy L., Djurisic T., Elekes Z., Feijão F., Florescu S., Franelić I. P., Kocsis E., Anna Kokkevi A., Lambrecht P., Lazar T. U., Nociar A., Oncheva S., Raitasalo K., Rupšienė L., Sierosławski J., Skriver M. V., Spilka S., Strizek J., Sturua L., Toçi E., Veresies K., Vorobjov S., Weihe P., Noor A., Matias J., Seitz N.-N., Piontek D., Svensson J., Anna A., Hibell B.ESPAD. (2016). ESPAD Report 2015. Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; Retrieved from http://www.espad.org/report/about-report.pdf (October 10, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur H. R., Cross J., Frank M., Welch M., White C. M., Rubenstein G., Moseley K., Mark M. (1991). Gambling and pathological gambling among university students. Addictive Behaviors, 16(6), 517–527. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(91)90059-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath D. S., Barrett S. P. (2009). The comorbidity of tobacco smoking and gambling: A review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Review, 28(6), 676–681. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00097.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak D. E. Aloe A. M. (2014). The prevalence of pathological gambling among college students: A meta-analytic synthesis, 2005–2013. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30(4), 819–843. doi:10.1007/s10899-013-9399-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters E. N., Nordeck C., Zanetti G., O’Grady K. E., Serpelloni G., Rimondo C., Blanco C., Welsh C., Schwartz R. P. (2015). Relationship of gambling with tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use among adolescents in the USA: Review of the literature 2000–2014. The American Journal on Addictions, 24(3), 206–216. doi:10.1111/ajad.12214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin C. (2002). An assessment of the validity and reliability of the SOGS-RA. Journal of Gambling Studies, 18(1), 67–93. doi:10.1023/A:1014584213557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presidenza del Consiglio Dei Ministri – Dipartimento Politiche Antidroga. (2013). 2013 National Report (2012 data) to the EMCDDA by the Reitox Italian Focal Point. Retrieved from http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/933/Italy%20National%20Report%202013.pdf (October 10, 2016).

- Shaffer H. J., Hall M. N. (1996). Estimating the prevalence of adolescent gambling disorders: A quantitative synthesis and guide toward standard gambling nomenclature. Journal of Gambling Studies, 12(2), 193–214. doi:10.1007/BF01539174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sourial N., Wolfson C., Zhu B., Quail J., Fletcher J., Karunananthan S., Bandeen-Roche K., Béland F., Bergman H. (2010). Correspondence analysis is a useful tool to uncover the relationships among categorical variables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(6), 638–646. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F., Brendgen M., Ladouceur R., Tremblay R. E. (2001). Gambling, delinquency, and drug use during adolescence: Mutual influences and common risk factors. Journal of Gambling Studies, 17(3), 171–190. doi:10.1023/A:1012201221601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volberg R., Gupta R., Griffiths M. D., Olason D., Delfabbro P. H. (2010). An international perspective on youth gambling prevalence studies. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 22, 3–38. doi:10.1515/IJAMH.2010.22.1.3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilber M. K., Potenza M. N. (2006). Adolescent gambling: Research and clinical implications. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 3(10), 40–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters K. C., Stinchfield R., Henly G. A., Schwartz R. H. (1991). Validity of adolescent self-report of alcohol and other drug involvement. International Journal of the Addictions, 25, 1379–1395. doi:10.3109/10826089009068469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters K. C., Stinchfield R. D., Fulkerson J. (1993). Toward the development of an adolescent gambling problem severity scale. Journal of Gambling Studies, 9(1), 63–84. doi:10.1007/BF01019925 [Google Scholar]