Abstract

Although current therapies can be successful at suppressing hepatitis B viral load, long-term viral cure is not within reach. Subsequent strategies combining pegylated interferon alfa with nucleoside/nucleotide analogues have not resulted in any major paradigm shift. An improved understanding of the hepatitis B virus (HBV) lifec ycle and virus-induced immune dysregulation has, however, revealed many potential therapeutic targets, and there are hopes that treatment of hepatitis B could soon be revolutionized. This review summarizes the current developments in HBV therapeutics—both virus directed and host directed.

Keywords: Antiviral therapy, Hepatitis B virus, Immunomodulators, Nonnucleoside antivirals, Nucleoside analogues

Introduction

Chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) remains a major healthcare problem, with an estimated 240 million persons infected worldwide [1]. In patients with untreated HBV infection the 5-year incidence of evolution to cirrhosis is 8–20%, and among those with cirrhosis the annual risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma is 2–5% [2–4]. Although the implementation of hepatitis B vaccines have been effective in reducing the incidence of HBV in vaccine recipients, significant declines in end-stage liver disease rates have not yet been seen.

Sustained virological response [i.e., hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seroconversion] is only seldom observed with currently approved HBV antiviral drugs [pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) and nucleoside/nucleotide analogues (NUCs)] because of the persistence of covalently circular closed DNA (cccDNA) in the nucleus of hepatocytes [5, 6]. Moreover, the widely used NUCs most likely have to be taken lifelong to prevent rebound [7], and while treatment with PEG-IFN does have a finite duration, the responses are suboptimal at best [7]. Novel therapeutic strategies are therefore needed.

With the recent revolutionary advances in the treatment of viral diseases such as hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (with direct-acting antivirals) and the development of multiple classes of anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) agents, the way may now be paved for similar advances in HBV therapeutics—with direct-acting antivirals and host-directed therapeutic strategies [8–10]. Improved understanding of the HBV life cycle has illustrated multiple potential antiviral targets, and there are many agents in preclinical and early clinical investigation, and other promising strategies for HBV clearance include immune modulators, whose potential is strongly supported by the fact that natural immune responses are capable of effectively preventing chronic HBV infection in 90% of infected adults.

This review aims to give a comprehensive overview of the major new drug developments in the treatment of HBV infection, specifically focusing on novel direct-acting antivirals and host-directed anti-HBV therapeutics. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Current Treatment Options for HBV Infection

The presently available antiviral treatments for HBV infection include two classes of therapeutic agents: PEF-IFN-α and NUCs. NUCs, which target HBV through inhibition of viral polymerase, are the most commonly used and have an excellent safety profile and tolerability. Most patients, however, require indefinite NUC therapy because of frequent relapse or reactivation of HBV infection after cessation of treatment, which is a hindrance for patient treatment adherence [9]. In contrast, PEG-IFN-α has predominant immunoregulatory effects along with limited direct antiviral properties [11, 12], and has a finite duration of therapy and a slightly higher occurrence of attaining anti-hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and anti-HBsAg seroconversion than with NUCs [13, 14]. However, interferon (IFN) sensitivity differs among the different HBV genotypes, and the main drawback of PEG-IFN-α is poor tolerability with frequent severe side effects, which considerably limits its use. Neither NUCs nor PEG-IFN-α is therefore optimal or results in long-term control or cure except in a minority of HBeAg-negative noncirrhotic individuals who experience durable HBsAg seroconversion, in which case therapy can be stopped under close monitoring.

There has therefore been interest in whether increased efficacy could be obtained by combination of these classes. Conceptually, combining PEG-IFN-α and NUC therapy could result in improved HBV control due to potential synergistic effects of their different mechanisms of actions, and there has been interest in simultaneous use (i.e., commencing both a NUC and PEG-IFN-α together) or sequentially or add-on administration [15, 16]. Earlier studies into simultaneous use of lamivudine with PEG-IFN-α showed more pronounced on-treatment virological response although without clear long-term benefit [14, 17]. Some newer studies investigating PEG-IFN-α combined with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) describe a significantly larger proportion of participants attaining HBsAg loss (9.1% vs 0% and 2.8%, respectively) and conversion to anti-HBsAg among patients receiving TDF plus PEG-IFN-α than in those receiving either TDF or PEG-IFN-α alone [18]. Two recent studies analyzing PEG-IFN-α therapy as an add-on to long-term entecavir (ETV) therapy demonstrated higher HBeAg seroconversion rates in the combination arm than in the ETV monotherapy arm [15, 16]. Nonetheless, a third trial examining PEG-IFN-α add-on therapy in patients receiving ETV did not establish superiority in comparison with the PEG-IFN group or patients allocated to ETV add-on treatment when receiving PEG-IFN-α [19]. A summary of recent published articles on this subject is depicted in Table 1. Overall, recent evidence suggests that in patients receiving long-term NUC therapy, both an add-on approach and sequential administration of PEG-IFN-α may have some minor advantages [15, 16, 20]. However, such combination therapy appears unlikely to lead to a paradigm shift or significant improvement for most HBV-infected individuals.

Table 1.

Summary of recent main randomized controlled trials demonstrating hepatitis B virus (HBV) virological responses in pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) and nucleoside/nucleotide analogue treatment strategies

| Study | Sample size (n) | Patient status | HBV genotype | Treatment regimen | Follow-up (weeks) | Virological response | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBeAg conversion (%) | HBsAg conversion (%) | HBV DNA suppression (%) | ||||||

| Add-on strategy | ||||||||

| Brouwer et al. [15] (ARES study) | 175 | HBeAg positive |

A 7% B 20% C 42% D 31% |

1. ETV for 48 weeks + PEG-IFN-α in weeks 24–48 2. ETV for 48 weeks |

96 |

26a 13 |

1 0 |

77 (< 202 IU/ml) 72 |

| Xie et al. [19] | 218 |

HBeAg positive Treatment naïve HBV DNA ≥ 105copies/ml |

– |

1. PEG-IFN-α for 48 weeks 2 PEG-IFN-α for 48 weeks + ETV in weeks 13–36 3. ETV for 24 weeks + PEG-IFN-α in weeks 21–68 |

72–92 |

31 25 26 |

1.4 4.1 1.4 |

40.3 (< 103 copies/ml) 31.5 37.0 |

| Sequential strategy | ||||||||

| Ning et al. [16] | 200 |

HBeAg positive ETV for 9—36 months HBV DNA < 104 copies/ml |

– |

1. PEG-IFN-α for 48 weeks 2. ETV for 48 weeks |

48 |

14.8a 6.1 |

4.3 0 |

72.0 (< 103 copies/ml) 97.8a |

| Piccolo et al. [81] | 30 |

HBeAg negative HBV DNA ≥ 203 copies/ml |

D 87% |

1. PEG-IFN-α for 24 weeks + LbT in weeks 25–48 2. LbT for 24 weeks + PEG-IFN-α in weeks 25–48 |

72 | – |

0 0 |

13.3 (< 203 IU/ml) 46.7a |

| Concomitant strategy | ||||||||

| Liu et al. [82] | 61 |

HBeAg positive HBV DNA ≥ 204 copies/ml |

– |

1 PEG-IFN-α + ADF for 52 weeks 2 PEG-IFN-α for 52 weeks |

52 |

36.7 25.8 |

3.3 0 |

76.7a (undetectable) 29.0 |

| Tangkijvanich et al. [83] | 125 |

HBeAg negative Treatment naïve HBV DNA ≥ 203 copies/ml |

B 19.8% C 78.6% Other 1.6% |

1. PEG-IFN-α + ETV for 48 weeks 2. PEG-IFN-α for 48 weeks |

96 | – |

3.2 7.9 |

38.1 (< 203 IU/ml) 41.3 |

| Marcellin et al. [84] (stopped because of adverse events) | 159 |

HBeAg positive Treatment naïve |

A 17% B 24% C 19% D 28% Other 4% Unknown 9% |

1. PEG-IFN-α + LbT for 24 weeks 2. LbT for 24 weeks 3. PEG-IFN-α for 24 weeks |

24 |

8 4 12 |

0 0 0 |

71c (< 302 copies/ml) 35 7 |

| Marcellin et al. [18] | 740 |

HBeAg positive or negative Treatment naïve HBV DNA ≥ 204 copies/ml (HBeAg positive) or ≥ 203 copies/ml (HBeAg negative) |

A 8% B 27% C 42% D 21% E–H 1% |

1. PEG-IFN-α + TDF for weeks 2. PEG-IFN-α for 16 weeks + TDF for 48 weeks 3. TDF for 120 weeks 4. PEG-IFN-α for 48 weeks |

72 |

25.0b 23.8 12.8 24.5 |

8.1 0.6 0 2.9 |

9.1 (< 15 IU/ml) 6.5 71.9d 9.2 |

PEG-IFN-α was administered at 180 mg/week or 1.5 μg/kg/week.

ADF adefovir 10 mg/day, ETV entecavir 0.5 mg/day, HBeAg hepatitis B e antigen, HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen, LdT telbivudine 600 mg/day, TDF tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg/day

a P < 0.05.

b P < 0.05 versus arm 3.

c P < 0.05 versus arms 2 and 3.

d P < 0.05 versus arms 1 and 2.

For What Should We Be Aiming?

The presently available agents can suppress plasma viremia and may occasionally change the plasma antigen profiles (HBeAg or HBsAg loss/seroconversion). They, however, have no (in the case of NUCs) or little (in the case of PEG-IFN) impact on hepatocyte HBV DNA levels, let alone in any way influence cccDNA levels intrahepatically. Therefore, these agents can control active disease, but do not lead to a radical virological cure [where all viral nucleic acid (i.e., cccDNA) is removed from the patient] or long-term control when the patient is not receiving treatment in most individuals. Even those few individuals who currently naturally or pharmacologically clear circulating HBV infection remain prone to reactivation/relapse of HBV infection if they become significantly immunosuppressed.

Therefore, paradigm shifts are required to lead to either long-term off-treatment suppression in most individuals or to complete radical virological cure. Can the newer treatments being investigated potentially lead to these end points as monotherapies or in combination?

Novel Direct-Acting Antivirals for HBV

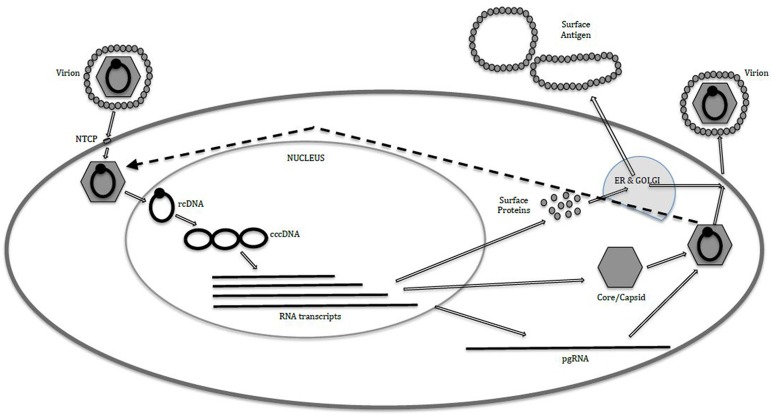

Very significant progress has been made in elucidating the life cycle of HBV and thereby identifying potential targets and agents for therapy. We will examine the major steps in the life cycle, illustrating the main potential drug classes and some of the leading contenders for direct-acting antivirals (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Life cycle of hepatitis B virus within the hepatocyte. cccDNA covalently closed circular DNA, ER endoplasmic reticulum, NTCP sodium–taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide, pgRNA pregenomic RNA, rcDNA relaxed circular DNA

Binding and Attachment of HBV to the Hepatocyte

HBV attaches initially to heparan sulfate proteoglycans on the hepatocyte cell surface, and then with high affinity binds its specific receptor—sodium–taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) [21]. This latter step can be targeted with a specific synthetic lipopeptide, myrcludex B, which has been shown to significantly inhibit viral NTCP binding and thereby reduce HBV viremia and serum surface antigen levels in humans [22, 23]. To date little toxicity has been demonstrated, although as the NTCP receptor’s natural activity is bile acid transportation, it will be of interest to determine if there will be some pharmacokinetic interactions with drugs metabolized via this route. Although seemingly potent at inhibiting the infection of uninfected hepatocytes, as a monotherapy it would not be expected to significantly influence hepatocyte HBV DNA levels (as these are replenished via pathways within the cell not requiring entry via NTCP binding; see later). It may well have an interesting role in combination, however, with other novel HBV agents and also in protecting the graft from infection in the setting of liver transplant in HBV infection.

Entry into the Cytoplasm, Nucleocapsid Release, and Entry of DNA into the Nucleus and Conversion to cccDNA

After fusion with the NTCP receptor, the virus enters the cytoplasm of the hepatocyte, is uncoated, and the HBV nucleic acid, in the form of relaxed circular DNA (rcDNA), leaves the nucleocapsid to subsequently enter the nucleus. Within the nucleus the rcDNA is converted into cccDNA. This is a vital step for the chronic nature of HBV infection as this cccDNA is highly stable and acts as a long-lived template for subsequent transcription of HBV RNA and proteins. It is the cccDNA (which effectively persists as an HBV minichromosome not integrated into the host DNA) that allows reactivation of apparently cleared HBV on significant immunosuppression, and is the major obstacle to radical cure of HBV infection.

Multiple agents are in preclinical development to target this cccDNA moiety: from zinc finger nucleases to disubstituted sulfonamide compounds, CRISPR–Cas9 technologies, and lymphotoxin beta receptor agonists [24–29]. However, to date, it is RNA interference methods that have entered human studies [30]. Mixtures of small interfering RNA molecules have shown activity in humans in decreasing serum surface antigen levels for prolonged periods after single dosing [31]. They are being developed to be pangenotypic, and some compounds are being targeted specifically at hepatocytes by combination with with ligands such as N-acetylgalactosamine, which promotes uptake via asialoglycoprotein receptor [32, 33]. However, issues remain with the development of stable delivery systems and, to date, studies have been small.

Transcription by cccDNA, Production of Viral Proteins, and Capsid Assembly

The cccDNA serves as a template for the transcription of viral RNA of two types. The first is the pregenomic RNA (pgRNA) that will produce the core and capsid proteins and also the nucleic acid template that ultimately enters the new nucleocapsid and is converted into DNA, creating a new infectious virion. The second is messenger RNA that is translated into the viral proteins—predominately the surface proteins (HBsAg and HBeAg) and X protein.

The capsid is created by multiple copies of the core protein combining. This step is one of the main targets of new HBV therapies, and current capsid assembly modulators/core inhibitors generally form one of two main classes. The first class contains compounds that promote capsid assembly but inhibit the entry of pgRNA into the immature nucleocapsid. This results in nucleocapsids that appear to be normal in geometry and size but are empty of nucleic acid and therefore noninfectious. Such compounds include phenylpropenamides and sulfamoylbenzamide derivatives [34, 35]. The other class contains compounds that directly inhibit the correct formation of the nucleocapsid itself, resulting in virus particles that are deformed with abnormal structure and size and appear noninfectious. Examples include the heteroaryldihydropyrimidines (e.g., BAY41-4109) [36] and NVR 3-778 [37, 38].

The activities of a further viral protein, the X protein, remain poorly defined. It appears to have a role in inhibiting the SMC5–6 complex and thereby promoting productive HBV gene expression [39]. Some preclinical work is ongoing at targeting this protein.

Nucleocapsid Coating and Conversion of pgRNA to rcDNA

HBV surface proteins (which have been processed within the host Golgi apparatus) now coat the nucleocapsid, and within this structure the pgRNA is converted by HBV polymerase to rcDNA. This latter step is the point of action of the currently available NUCs. There are new NUCs in development (e.g., besifovir, CMX 157, AGX-1009, and MIV-210) but it is currently unclear what advantages they will have compared with the existing agents [31, 40, 41].

Surface Protein Secretion from the Hepatocyte

It has long been recognized that large quantities of viral proteins, especially HBsAg, are secreted from the hepatocyte unassociated with virions. It is thought that this extra protein acts to absorb potentially neutralizing antibodies in the host plasma and also to induce a state of immune exhaustion and tolerance to the virus. HBsAg release inhibitors have been developed (e.g., REP 2139 and REP 2165) that appear potent in preventing the release of HBsAg in humans and thereby decreasing serum HBsAg levels and also potentially promoting surface antibody seroconversion [42, 43]. Whether these compounds may cause detrimental intrahepatocyte accumulation of HBsAg is still to be determined.

Release of Virions and Intrahepatocyte cccDNA Replenishment

Once coated in surface protein, the virions are released from the hepatocyte to infect new cells. But not all nucleocapsids are released, with some diverted to replenish the nuclear cccDNA compartment. Some agents that affect the formation of nucleocapsids, such as the capsid assembly inhibitor JNJ-379, have been shown to ultimately decrease cccDNA levels. Berke et al. [35] suggested that this is presumably by preventing the cccDNA replenishment cycle through blocking of pgRNA synthesis.

Therefore, multiple potential therapeutic targets have become apparent as a result of improved understanding of the cellular life cycle of HBV (Table 2). It is quite probable, however, that none of these agents as monotherapies will result in radical cure of HBV infection, and combination direct-acting antivirals may be required. Even with such combinations it may well be that host-directed therapies will also be required to reverse immune exhaustion and tolerance, and therefore promote viral clearance and cure.

Table 2.

Overview of ongoing clinical trials for new hepatitis B virus therapeutics

| Compound | Phase |

|---|---|

| Entry inhibitors | |

| Myrcludex B | Phase I |

| RNA interference | |

| ALN-HBV | Phase I–II |

| ARC-520 | Phase II |

| ARB-1467 | Phase II |

| Lunar-HBV | Preclinical |

| BB-HB-331 | Preclinical |

| Ionis HBVRx (GSK3228836) | Phase I |

| IONIS-HBVLRx (GSK33389404) | Phase I |

| Capsid assembly modulators/core inhibitors | |

| GLS-4 (morphothiadine mesilate) | Phase II |

| NVR 3-778 | Phase Ia |

| BAY41-4109 | Phase I |

| JNJ56136379 | Phase I |

| Core protein allosteric modifier | Phase I |

| Nucleoside/nucleotide analogues | |

| AGX-1009 (prodrug of tenofovir) | Phase III |

| LB80380 (besifovir) | Phase III |

| CMX-157 (prodrug of tenofovir) | Phase IIa |

| Surface antigen/release inhibitors | |

| REP 2139 and REP 2165 | Phase II |

| RO7020322 (RG7834) | Phase I |

| GC 1102 | Phase II |

| Therapeutic vaccines | |

| GS-4774 (recombinant antigen containing X, Env, core epitopes) | Phase II |

| ABX-203 (recombinant antigen containing HBsAg and HBcAg) | Phase II |

| TG-1050 (nonreplicative adenovirus encoding a large fusion protein (truncated core, modified Pol, and 2 Env domains) | Phase I |

| INO-1800 (DNA plasmids encoding HBsAg and HBcAg) | Phase I |

| FP-02.2 (HepTcell) (peptide encoding CD4+ and CD8+ epitopes) | Phase I |

| Innate immune defense pathway | |

| GS 9620 | Phase II |

| RO6864018 (RG7795, ANA773) | Phase II |

| SB9200 | Phase II |

This table provides a current overview of compounds in clinical development to the best of our knowledge.

HBcAg hepatitis B core antigen, HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen

Novel Immunological Targets for HBV Therapy

Cellular Immune Response

The human cellular immune response plays a key role in attaining immune control and viral clearance after HBV infection [44, 45]. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) have been identified to be the major contributing factor for HBV clearance [46]. Two signal types are mandatory to activate T cells: interaction between T-cell receptors and antigens presented by major histocompatibility complex molecules on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) on the one hand, and interaction between co-stimulatory or co-inhibitory receptors on T cells with their ligands on APCs on the other [47, 48]. The latter molecules can amplify or inhibit active immune responses and are called “immune checkpoints” [49]. Immune checkpoints are physiologically necessary for maintaining self-tolerance and minimizing collateral host tissue destruction [50].

As a consequence of persistently high antigen levels in chronic viral infections, CTLs and CD4+ cells have been observed to become functionally exhausted [51–53]. This was first discovered in mice infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infected that exhibited CTLs with reduced capability to kill infected cells and reduced cytokine secretion despite persisting indefinitely [54, 55]. To date, T-cell exhaustion, classified by the overexpression of inhibitory receptors such as programmed death 1 (PD1), CTL-associated antigen 4, and lymphocyte activation gene 3 protein, is a hallmark of chronic viral infection and has been observed in infections with HIV, HCV, human T-cell lymphotropic virus, and HBV [56, 57].

In HBV, enhanced PD1 expression by CTLs and CD4+ cells has been demonstrated in mouse models of persistent HBV infection [54] and on human HBV-specific exhausted CTLs in chronic HBV infection [58].

Therefore, targeting these inhibitory receptors and thereby reversing CTL responses (i.e., rescuing exhausted T cells) is one of the therapeutic strategies currently being explored (Table 3). For example, in chronic infection with woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV; a virus closely related to HBV), infected woodchucks were treated with a combination of ETV, therapeutic DNA vaccination, and PD1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibodies, which led to sustained immune control of the infection and even viral clearance in some woodchucks [57]. In addition, an ex vivo study using intrahepatic and peripheral T cells from patients with chronic HBV or HCV infection observed increased cytokine secretion of HBV-specific T cells in the presence of APCs treated with anti-PD-L1 in combination with stimulation of the co-stimulatory receptor CD137 [59].

Table 3.

Summary of immune checkpoint inhibitors for targets of potential interest for hepatitis B virus immunotherapy

| Target | Target function | Binding partner | Drug | Indication | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTLA4 | Inhibitory receptor | CD80, CD86 | Ipilimumab |

Melanoma Multiple malignancies |

FDA approved Phase II/phase III |

| Tremelimumab | Malignant mesothelioma | FDA approved | |||

| PD1 | Inhibitory receptor | PD-L1, PD-L2 |

Pembrolizumab Nivolumab Pidilizumab AMP-224 MDX-1106 |

Melanoma Melanoma Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma Colorectal cancer Hepatitis C virus Multiple malignancies |

FDA approved FDA approved Phase II Phase I Phase I |

| PD-L1 | PD1 ligand | PD-1 |

Avelumab BMS-936559 MPDL33280A MEDI4736 |

Multiple malignancies HIV-1, multiple malignancies Multiple malignancies Multiple malignancies |

Phase II Phase I Phase I Phase I |

| CD137 | Stimulatory receptor | CD137L |

BMS-663513 PF-05082566 |

Solid tumors Lymphoma |

Phase I/II Phase I |

CD137L CD137 ligand, CTLA4 cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated antigen 4, HIV-1 human immunodeficiency virus 1PD1 programmed death 1, PD-L1 programmed death 1 ligand 1, PD-L2 programmed death 1 ligand 2

However, some important points should be taken into account. First, sufficient presence of HBV-specific exhausted T cells may be crucial to the effectiveness of these drugs [38]. As such it may prove to be difficult to determine which patients should be treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Second, longer infection duration with excessive antigen exposure may lead to the irreversible exhaustion of T cells [52, 60]. Combined treatment with other antiviral drugs may thus be necessary to bring down antigen levels before initiation of immunotherapy [39]. Lastly, because of the mechanisms of action of immune checkpoint inhibitors, important immune-related adverse events have been observed in trials with CTL-associated antigen 4, PD1, and PD-L1 antibodies, affecting several organ systems, including the liver [51, 61–63].

Toll-like Receptor 7 and Toll-like Receptor 8 Agonists

Another HBV strategy, targeting the innate immune system, is to activate Toll-like receptors (TLRs) as activation of virus-specific TLRs leads to production of type I IFNs (mainly IFN-α and IFN-β) [54]. IFN-β in particular is capable of inhibiting HBV replication through destabilization of pgRNA capsids and interfering with their assembly. TLR7—present mainly in the endolysosomal compartment of plasmacytoid dendritic cells and B cells—can induce intrahepatic type I IFN responses without causing systemic harmful symptoms. As an activator of the innate immune response in the liver, it became a major focus in TLR agonist trials focusing on viral clearance of HBV [64].

GS-9620, an oral TLR7 agonist, was demonstrated in animal studies to activate expression of IFN-stimulating genes, while early human studies showed transient increases in the levels of IFN-γ-induced protein 10 (also known as IP-10) 8 h after GS-9620 administration, suggesting an IFN-y response [65, 66]. In a recent phase II trial, three different lengths of GS-9620 dosing (4, 8, and 12 weeks) were investigated in 156 chronic virally suppressed HBV infected patients [67]. Within each cohort, patients were randomized to receive three different doses (1, 2, or 4 mg). Although GS-9620 administration was safe and well tolerated, there was no significant decline in HBsAg levels. Additional in-depth analysis of HBV-specific T-cell and natural killer cell responses showed improved interplay between the two cell types, together with a transient improvement of T-cell response [68]. This was most notable for the highest dose of GS-9620 (4 mg).

These somewhat disappointing results are in contrast to the results of earlier animal studies in both chimpanzees and woodchucks in which GS-9620 was demonstrated to induce rapid sustained reduction in serum and liver HBV DNA levels together with loss of woodchuck hepatitis surface antigen (WHsAg) in woodchucks with chronic WHV infection [69, 70]. One possible explanation could be the difference in dosing—from 1 to 2 mg/kg in animal trials to 1–4 mg per patient in human studies. However, further research into this TLR7 agonist was subsequently discontinued.

TLR8-mediated recognition has been associated with viral infections. A first demonstration of its possible role in HBV infection came from an in vitro study by Jo et al. [71] demonstrating detectable intrahepatic IFN-γ production on stimulation of mononuclear cells by a TLR8 agonist [71]. Moreover, TLR8 expression and function was impaired in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with chronic HBV infection compared with healthy controls [72]. When these HBeAg-negative patients were treated with a 48-week course of PEG-IFN-α, TLR8 messenger RNA level could discriminate between those who achieved a complete response and those who did not. This has led to a number of drugs in development targeting TLR8.

HBV Therapeutic Vaccines

The concept behind therapeutic vaccines is the generation of new HBV-specific T cells capable of controlling chronic HBV infection. HBV therapeutic vaccines have been shown to restore both T-cell responses and IFN-γ production [73]. In patients with high levels of virus in the blood, HBV-specific CD8 T cells have been shown to be dysfunctional although they are necessary for future viral control [58, 74, 75]. Therefore, in the setting of effective oral anti-HBV therapy with NUCs, therapeutic vaccines may have a role in the restoration of T-cell control.

The first HBV therapeutic vaccine to be studied in HBV-infected humans was GS-4774, a yeast-based T-cell vaccine containing HBV core, surface, and X proteins that has been shown to be immunogenic in mouse models and healthy volunteers. In a small phase II study the effects of GS-4774 were investigated on HBV-specific T-cell responses in 12 naïve HBeAg-negative genotype D patients with chronic HBV infection [76]. They received six consecutive monthly doses of the vaccine in combination with TDF. Although T-cell function improved, mostly an effect on CD8 cells, it was insufficient to induce a substantial decline of HBsAg levels. Multiple other vaccines are currently in development (early phase). These vaccines include vaccines targeting the preS1 domain [77] and the immune-stimulant vaccine ABX203 [78].

It might be that a combination of the aforementioned strategies (directed at reversal of T-cell exhaustion and generation of new T-cell responses) in patients with HBV infection stably suppressed with NUCs might be a way forward. A recent study in WHV-infected woodchucks investigated such a triple therapy combination, consisting of therapeutic vaccine (i.e., DNA plasmids expressing woodchuck hepatitis core antigen and WHsAg), the immune checkpoint inhibitor anti-PD-L1, and ETV. Sustained immunological control with the development of antibodies against WHsAg and even viral clearance in some woodchucks was achieved [79]. Recently, a phase I trial evaluating the efficacy of anti-PD1 treatment with or without GS-4774 in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B patients was published [80]. A single dose of anti-PD1 resulted in a significant decline in HBsAg levels, but with no apparent added benefit of GS-4774.

Conclusions

Although treatment with the current nucleoside/nucleotide inhibitors is very successful in suppressing HBV DNA to undetectable levels, functional let alone sterilizing cures are not within reach for the vast majority of HBV-infected patients. New exciting advances have led to new compounds targeting multiple steps in the viral life cycle as well as approaches to attenuate virus-induced immune dysregulation. Further research into these agents remains problematic however, with key issues needing to be resolved. First, firm therapy-related end points of cure need to be establish. Second, it is likely that combination therapies will be required, and it is currently hard to envisage how the most promising combination of drug targets can be determined. Thereafter, however, the future looks bright for patients with chronic HBV infection.

Acknowledgements

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for the manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Disclosures

Joop Arends provides advisory services for MSD, Abbvie, BMS, Janssen, Gilead and Viiv. Joop Arends has also received research grants from MSD, ViiV, BMS and Abbvie. Andrew Ustianowski provides advisory services for Abbvie, Gilead, Janssen, MSD, ViiV. Faydra Lieveld and Shazaad Ahmad have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies, and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/32CCF0601C683DB1.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the prevention, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis B infection. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [PubMed]

- 2.Fattovich G. Natural history and prognosis of hepatitis B. Semin Liv Dis. 2003;23(1):47–58. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Yim HJ, Lok AS. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: what we knew in 1981 and what we know in 2005. Hepatology. 2006;43(2 Suppl 1):S173–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.McMahon BJ. The natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2009;49(5 Suppl):S45–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Moraleda G, Saputelli J, Aldrich CE, Averett D, Condreay L, Mason WS. Lack of effect of antiviral therapy in nondividing hepatocyte cultures on the closed circular DNA of woodchuck hepatitis virus. J Virol. 1997;71:9392–9399. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9392-9399.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong DK-H, Seto W-K, Fung J, Ip P, Huang F-Y, Lai C-L, et al. Reduction of hepatitis B surface antigen and covalently closed circular DNA by nucleos(t)ide analogues of different potency. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1004–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang K, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Murad MH. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63:261–283. doi: 10.1002/hep.28156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noell BC, Besur SV. Changing the face of hepatitis C management – the design and development of sofosbuvir. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2015;9:2367. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S65255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henrich TJ, Kuritzkes DR. HIV-1 entry inhibitors: recent development and clinical use. Curr Opin Virol. 2013;3:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eggink D, Berkhout B, Sanders RW. Inhibition of HIV-1 by fusion inhibitors. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:3716–3728. doi: 10.2174/138161210794079218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun J, Xie Q, Tan D, Ning Q, Niu J, Bai X, et al. The 104-week efficacy and safety of telbivudine-based optimization strategy in chronic hepatitis B patients: a randomized, controlled study. Hepatology. 2014;59:1283–1292. doi: 10.1002/hep.26885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Micco L, Peppa D, Loggi E, Schurich A, Jefferson L, Cursaro C, et al. Differential boosting of innate and adaptive antiviral responses during pegylated-interferon-alpha therapy of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2013;58:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buster EHCJ, Flink HJ, Cakaloglu Y, Simon K, Trojan J, Tabak F, et al. Sustained HBeAg and HBsAg loss after long-term follow-up of HBeAg-positive patients treated with peginterferon α-2b. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:459–467. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau GKK, Piratvisuth T, Luo KX, Marcellin P, Thongsawat S, Cooksley G, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a, lamivudine, and the combination for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2682–2695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brouwer WP, Xie Q, Sonneveld MJ, Zhang N, Zhang Q, Tabak F, et al. Adding pegylated interferon to entecavir for hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B: a multicenter randomized trial (ARES study) Hepatology. 2015;61:1512–1522. doi: 10.1002/hep.27586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ning Q, Han M, Sun Y, Jiang J, Tan D, Hou J, et al. Switching from entecavir to pegIFN alfa-2a in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: a randomized open-label trial (OSST trial) J Hepatol. 2014;61:777–784. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janssen HLA, van Zonneveld M, Senturk H, Zeuzem S, Akarca US, Cakaloglu Y, et al. Pegylated interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365:123–129. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17701-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcellin P, Ahn SH, Ma X, Caruntu FA, Tak WY, Elkashab M, et al. Combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and peginterferon alpha-2a increases loss of hepatitis B surface antigen in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(134–144):e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie Q, Zhou H, Bai X, Wu S, Chen J-J, Sheng J, et al. A randomized, open-label clinical study of combined pegylated interferon alfa-2a (40KD) and entecavir treatment for hepatitis B “e” antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1714–1723. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bourliere M, Rabiega P, Ganne-Carrie N, Serfaty L, Marcellin P, Pouget N, et al. HBsAg clearance after addition of 48 weeks of PEGIFN in HBeAg negative CHB patients on nucleos(t)ide therapy with undetectable HBV DNA for at least one year: a multicenter randomized controlled phase III trial ANRS-HB06 PEGAN study: preliminary findings. Hepatology. 2014;60:1094A–1095A. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan H, Zhong G, Xu G, He W, Jing Z, Gao Z, et al. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. Elife. 2012;1:e00049. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blank A, Markert C, Hohmann N, Carls A, Mikus G, Lehr T, et al. First-in-human application of the novel hepatitis B and hepatitis D virus entry inhibitor myrcludex B. J Hepatol. 2016;65:483–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volz T, Allweiss L, ḾBarek MB, Warlich M, Lohse AW, Pollok JM, et al. The entry inhibitor myrcludex-B efficiently blocks intrahepatic virus spreading in humanized mice previously infected with hepatitis B virus. J Hepatol. 2013;58:861–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Zimmerman KA, Fischer KP, Joyce MA, Tyrrell DLJ. Zinc finger proteins designed to specifically target duck hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA inhibit viral transcription in tissue culture. J Virol. 2008;82:8013–8021. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00366-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cai Y, Chai D, Wang R, Liang B, Bai N. Colistin resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii: clinical reports, mechanisms and antimicrobial strategies. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:1607–1615. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lucifora J, Xia Y, Reisinger F, Zhang K, Stadler D, Cheng X, et al. Specific and nonhepatotoxic degradation of nuclear hepatitis B virus cccDNA. Science. 2014;343:1221–1228. doi: 10.1126/science.1243462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong C, Qu L, Wang H, Wei L, Dong Y, Xiong S. Targeting hepatitis B virus cccDNA by CRISPR/Cas9 nuclease efficiently inhibits viral replication. Antivir Res. 2015;118:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X, Hao R, Chen S, Guo D, Chen Y. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus by the CRISPR/Cas9 system via targeting the conserved regions of the viral genome. J Gen Virol. 2015;96:2252–2261. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennedy EM, Bassit LC, Mueller H, Kornepati AVR, Bogerd HP, Nie T, et al. Suppression of hepatitis B virus DNA accumulation in chronically infected cells using a bacterial CRISPR/Cas RNA-guided DNA endonuclease. Virology. 2015;476:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gish RG, Given BD, Lai C-L, Locarnini SA, Lau JYN, Lewis DL, et al. Chronic hepatitis B: virology, natural history, current management and a glimpse at future opportunities. Antiviral Res. 2015;121:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuen M-F, Chan HLY, Liu K, Given BD, Schluep T, Hamilton J, et al. Differential reductions in viral antigens expressed from CCCDNAVS integrated DNA in treatment naïve HBEAG positive and negative patients with chronic HBV after RNA interference therapy with ARC-520. J Hepatol. 2016;64:S390–S391. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(16)00606-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sepp-Lorenzino L, Sprague AG, Mayo T. Parallel 4: hepatitis B: novel treatments and treatment targets: 36—GalNAc-siRNA conjugate ALN-HBV targets a highly conserved, pan-genotypic X-orf viral site and mediates profound and durable HBsAg silencing in vitro and in vivo. Hepatology. 2015;62:222A–225A. doi: 10.1002/hep.28171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Billioud G, Kruse RL, Carrillo M, Whitten-Bauer C, Gao D, Kim A, et al. In vivo reduction of hepatitis B virus antigenemia and viremia by antisense oligonucleotides. J Hepatol. 2016;64:781–789. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mani N, Cole AG, Ardzinski A, Cai D, Cuconati A, Dorsey BD, et al. The HBV capsid inhibitor AB-423 exhibits a dual mode of action and displays additive/synergistic effects in in vitro combination studies. Hepatology. 2016;64(Suppl S1):123A–4A.

- 35.Berke JM, Dehertogh P, Vergauwen K, van Damme E, Raboisson P, Pauwels F, et al. Capsid assembly modulator JNJ-56136379 prevents de novo infection of primary human hepatocytes with hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 2016;64(Suppl S1):124A.

- 36.Stray SJ, Zlotnick A. BAY 41‐4109 has multiple effects on hepatitis B virus capsid assembly. J Mol Recognit. 2006;19:542–548. doi: 10.1002/jmr.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuen M-F, Kim DJ, Weilert F, Chan HL-Y, Lalezari JP, Hwang SG, et al. Phase 1b efficacy and safety of NVR 3-778, a first-in-class HBV core inhibitor, in HBeAg-positive patients with chronic HBV infection. Hepatology. 2015;62:1385A–1386A. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuen M-F, Kim DJ, Weilert F, Chan H-Y, Lalezari JP, Hwang SG, et al. NVR 3-778, a first-in-class HBV core inhibitor, alone and in combination with peg-interferon (pegIFN), in treatment-naive HBeAg-positive patients: early reductions in HBV DNA and HBeAg. J Hepatol. 2016;64:S210–S211. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(16)00175-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Decorsiere A, Mueller H, Van Breugel PC, Abdul F, Gerossier L, Beran RK, et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein identifies the Smc5/6 complex as a host restriction factor. Nature. 2016;531:386–406. doi: 10.1038/nature17170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Painter GR, Almond MR, Trost LC, Lampert BM, Neyts J, De Clercq E, et al. Evaluation of hexadecyloxypropyl-9-R-[2-(phosphonomethoxy) propyl]-adenine, CMX157, as a potential treatment for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and hepatitis B virus infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3505–3509. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00460-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Michalak TI, Zhang H, Churchill ND, Larsson T, Johansson N-G, Öberg B. Profound antiviral effect of oral administration of MIV-210 on chronic hepadnaviral infection in a woodchuck model of hepatitis B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3803–3814. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00263-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bazinet M, Pantea V, Cebotarescu V, Cojuhari L, Jimbei P, Albrecht J, et al. Initial follow up results from the REP 301 trial: safety and efficacy of REP 2139-Ca and pegylated interferon alpha-2a in caucasian patients with chronic HBV/HDV co-infection. In: Hepatology. 2016;64(Suppl S1):912A.

- 43.Bazinet M, Pantea V, Cebotarescu V, Cojuhari L, Jimbei P, Albrecht J, et al. Update on the safety and efficacy of REP 2139 monotherapy and subsequent combination therapy with pegylated interferon alpha-2A in Caucasian patients with chronic HBV/HDV co-infection. J Hepatol. 2016;64:S584–S585. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(16)01073-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bertoletti A, Gehring AJ. The immune response during hepatitis B virus infection. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:1439–1449. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81920-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luckheeram RV, Zhou R, Verma AD, Xia B. CD4+T cells: differentiation and functions. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:925135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Thimme R, Wieland S, Steiger C, Ghrayeb J, Reimann KA, Purcell RH, et al. CD8+ T cells mediate viral clearance and disease pathogenesis during acute hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol. 2003;77:68–76. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.68-76.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Andrian UH, Mackay CR. T-cell function and migration—two sides of the same coin. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1020–1034. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010053431407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen L, Flies DB. Molecular mechanisms of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:227. doi: 10.1038/nri3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharon E, Streicher H, Goncalves P, Chen HX. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical trials. Chin J Cancer. 2014;33:434. doi: 10.5732/cjc.014.10122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu Y. Immune checkpoint drug goes viral: developing new treatment paradigm for chronic viral infection. J Hum Virol Retroviral. 2014;1:4. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wherry EJ. T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:492–499. doi: 10.1038/ni.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maini MK, Schurich A. The molecular basis of the failed immune response in chronic HBV: therapeutic implications. J Hepatol. 2010;52:616–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bertoletti A, Ferrari C. Innate and adaptive immune responses in chronic hepatitis B virus infections: towards restoration of immune control of viral infection. Gut. 2012;61:1754–1764. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, Robert C, Grossmann K, McDermott D, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2006–2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tiegs G, Lohse AW. Immune tolerance: what is unique about the liver. J Autoimmun. 2010;34:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hotchkiss RS, Moldawer LL. Parallels between cancer and infectious disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:380–383. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1404664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boni C, Fisicaro P, Valdatta C, Amadei B, Di Vincenzo P, Giuberti T, et al. Characterization of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-specific T-cell dysfunction in chronic HBV infection. J Virol. 2007;81:4215–4225. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02844-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fisicaro P, Valdatta C, Massari M, Loggi E, Ravanetti L, Urbani S, et al. Combined blockade of programmed death-1 and activation of CD137 increase responses of human liver T cells against HBV, but not HCV. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1576–1585. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blackburn SD, Crawford A, Shin H, Polley A, Freeman GJ, Wherry EJ. Tissue-specific differences in PD-1 and PD-L1 expression during chronic viral infection: implications for CD8 T-cell exhaustion. J Virol. 2010;84:2078–2089. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01579-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ott JJ, Stevens GA, Groeger J, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine. 2012;30:2212–2219. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Corsello SM, Barnabei A, Marchetti P, De Vecchis L, Salvatori R, Torino F. Endocrine side effects induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:1361–1375. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Postow MA. Managing immune checkpoint-blocking antibody side effects. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ B. 2015;35:76–83. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2015.35.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Funk E, Kottilil S, Gilliam B, Talwani R. Tickling the TLR7 to cure viral hepatitis. J Transl Med. 2014;12:129. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fosdick A, Zheng J, Pflanz S, Frey CR, Hesselgesser J, Halcomb RL, et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of GS-9620, a novel Toll-like receptor 7 agonist, demonstrate interferon-stimulated gene induction without detectable serum interferon at low oral doses. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;348:96–105. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.207878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gane EJ, Lim Y-S, Gordon SC, Visvanathan K, Sicard E, Fedorak RN, et al. The oral toll-like receptor-7 agonist GS-9620 in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2015;63:320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Janssen HL, Brunetto MR, Kim YJ, Ferrari C, Massetto B, Nguyen A-H, et al. Safety and efficacy of GS-9620 in Virally-suppressed patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;64(Suppl S1):913A–4A. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Boni C, Vecchi A, Rossi M, Laccabue D, Giuberti TG, Alfieri A, et al. TLR-7 agonist GS-9620 can improve HBV-specific T cell and NK cell responses in nucleos(t)ide suppressed patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;64(Suppl S1):7A.

- 69.Lanford RE, Guerra B, Chavez D, Giavedoni L, Hodara VL, Brasky KM, et al. GS-9620, an oral agonist of Toll-like receptor-7, induces prolonged suppression of hepatitis B virus in chronically infected chimpanzees. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1508–1517. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Menne S, Tumas DB, Liu KH, Thampi L, AlDeghaither D, Baldwin BH, et al. Sustained efficacy and seroconversion with the Toll-like receptor 7 agonist GS-9620 in the Woodchuck model of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2015;62:1237–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jo J, Tan AT, Ussher JE, Sandalova E, Tang X-Z, Tan-Garcia A, et al. Toll-like receptor 8 agonist and bacteria trigger potent activation of innate immune cells in human liver. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004210. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Deng G, Ge J, Liu C, Pang J, Huang Z, Peng J, et al. Impaired expression and function of TLR8 in chronic HBV infection and its association with treatment responses during peg-IFN-α-2a antiviral therapy. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2017;41:386–39. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Gaggar A, Coeshott C, Apelian D, Rodell T, Armstrong BR, Shen G, et al. Safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of GS-4774, a hepatitis B virus-specific therapeutic vaccine, in healthy subjects: a randomized study. Vaccine. 2014;32:4925–4931. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maini MK, Boni C, Lee CK, Larrubia JR, Reignat S, Ogg GS, et al. The role of virus-specific CD8+ cells in liver damage and viral control during persistent hepatitis B virus infection. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1269–1280. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.8.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Webster GJM, Reignat S, Brown D, Ogg GS, Jones L, Seneviratne SL, et al. Longitudinal analysis of CD8+ T cells specific for structural and nonstructural hepatitis B virus proteins in patients with chronic hepatitis B: implications for immunotherapy. J Virol. 2004;78:5707–5719. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5707-5719.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Boni C, Rossi M, Vecchi A, Laccabue D, Giuberti T, Alfieri A, et al. PS-050 - combined GS-4774 and tenofovir therapy can improve HBV-specific T cell responses in patients with chronic active hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2017;66:S29. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(17)30321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bian Y, Zhang Z, Sun Z, Zhao J, Zhu D, Wang Y, et al. Vaccines targeting PreS1 domain overcome immune tolerance in HBV carrier mice. Hepatology. 2017;66:1067–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Wedemeyer H, Hui AJ, Sukeepaisarnjaroen W, Tangkijvanich P, Su WW, Nieto GEG, et al. LBP-518 - therapeutic vaccination of chronic hepatitis B patients with ABX203 (NASVAC) to prevent relapse after stopping NUCs: contrasting timing rebound between tenofovir and entecavir. J Hepatol. 2017;66:S101. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(17)30463-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu J, Kosinska A, Lu M, Roggendorf M. New therapeutic vaccination strategies for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Virol Sin. 2014;29:10–16. doi: 10.1007/s12250-014-3410-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gane E, Gaggar A, Nguyen AH, Subramanian GM, McHutchison JG, Schwabe C, et al. PS-044 - a phase1 study evaluating anti-PD-1 treatment with or without GS-4774 in HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B patients. J Hepatol. 2017;66:S26–S27. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(17)30315-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Piccolo P, Lenci I, di Paolo D, Demelia L, Sorbello O, Nosotti L, et al. A randomized controlled trial of sequential pegylated interferon-alpha and telbivudine or vice versa for 48 weeks in hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther. 2013;18:57–64. doi: 10.3851/IMP2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu Y-H, Wu T, Sun N, Wang G-L, Yuan J-Z, Dai Y-R, et al. Combination therapy with pegylated interferon alpha-2b and adefovir dipivoxil in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B versus interferon alone: a prospective, randomized study. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol Med Sci. 2014;34:542–547. doi: 10.1007/s11596-014-1312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tangkijvanich P, Chittmittraprap S, Poovorawan K, Limothai U, Khlaiphuengsin A, Chuaypen N, et al. A randomized clinical trial of peginterferon alpha-2b with or without entecavir in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B: role of host and viral factors associated with treatment response. J Viral Hepat. 2016;23:427–38. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Marcellin P, Wursthorn K, Wedemeyer H, Chuang W-L, Lau G, Avila C, et al. Telbivudine plus pegylated interferon alfa-2a in a randomized study in chronic hepatitis B is associated with an unexpected high rate of peripheral neuropathy. J Hepatol. 2015;62:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]