Abstract

Introduction

Fatigue is a frequent, disabling, and difficult to treat symptom in neurological disease and in other stress-related conditions; Integrated Imaginative Distention (IID) is a therapy combining muscular and imaginative relaxation, feasible also in disabled subjects; the DIMMI SI trial was planned to evaluate IID efficacy on fatigue.

Methods

The design was a parallel, randomised 1:1 (intervention:waiting list), controlled, open-label trial. Participants were persons with multiple sclerosis (pwMS), persons with insomnia (pwINS), and health professionals (HP) as conditions related to fatigue and stress. The primary outcome was the post-intervention change of fatigue; secondary outcomes were changes in insomnia, stress, and quality of life (QoL). Eight IID weekly training group sessions were delivered by a skilled psychotherapist. The study lasted 12 months.

Results

One hundred and forty-four subjects were enrolled, 48 for each condition. The mean change in Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS) score among exposed was 7.7 [95% CI 1.1, 14.4] (P = 0.023) in pwMS; 7.1 [1.9, 12.3] (P = 0.007) among pwINS, and 11.3 [4.3, 18.2] among HP (P = 0.002). At the last follow-up, the benefit was confirmed on physical fatigue for pwMS, on total fatigue for pwINS and HP.

Conclusions

DIMMI SI is the first randomized controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of IID on fatigue. IID resulted a complementary intervention to reduce fatigue in stress-related conditions, in both health and disease status. NCT02290990ClinicalTrials.gov.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40120-017-0081-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Behaviour/addiction, Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases, Sleep disorders

Introduction

Complex to define and quantify for its subjective and multidimensional nature, fatigue is a normal phenomenon referred to both physical and mental processes that is considered pathological when disabling [1]. Fatigue can frequently affect different neurological conditions presenting specific features, and its intensity is not associated with the nature and severity of underlying disease [2]. Its multifactorial pathogenesis includes neurological dysfunctions and hormonal imbalances, whereas psychological and sleep disorders could act as triggers [3–5]. In multiple sclerosis (MS), fatigue represents a main symptom and one of the major reasons for disability, unemployment, and impaired work, being often associated with poor sleep [6, 7]. In insomniac persons, fatigue represents one of the first reasons to ask for treatment [8]. Also, in other chronic, stress-related conditions, such as health professions, fatigue is a frequent symptom, that in association with poor sleep can worsen job performances [9, 10].

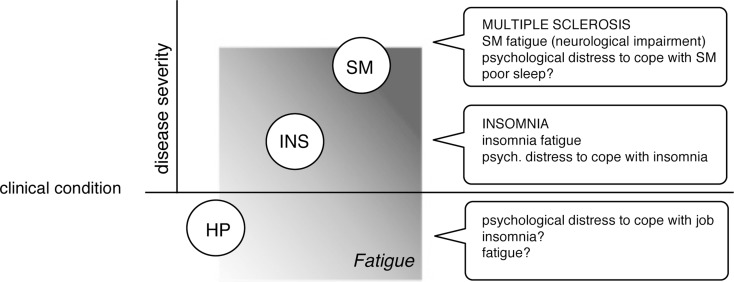

Effective treatments for fatigue are not available [2]. Some promising and discussed evidence in MS comes from non-pharmacological interventions (n-PI) [11–13] that are still insufficient to support or refute their implementation. Among n-PI, the Integrated Imaginative Distention (IID) [14–16] is a therapy that joins interventions previously proven effective on MS fatigue: relaxation, self-awareness, and psychotherapy [12, 17]. We decided to perform a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the IID effectiveness on fatigue, selecting three chronic, and stress related conditions which present this symptom responsive to n-PI: MS, insomnia (Ins), and health professions (Hp) [18–20]. MS was considered the target of the trial as the most complex status, while Ins and Hp were selected as parallel comparison conditions, potentially sharing fatigue, distress, and poor sleep. In our assumption IID therapy response could be differentiated in the three conditions based on the efficacy on psychological distress, sleep disorder, and fatigue (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Trial assumption

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The trial design was prospective, randomized (intervention vs. waiting list), controlled with three parallel conditions, open-label. Treating physician and data entry operator were blind to intervention assignment. Randomization was centrally performed using a computer-generated central allocation list 1:1, stratified by sex and condition. The trial lasted 12 months, including 1 month for enrollment, 2 months for intervention, 6 months for follow-up, and 3 months for final satisfaction questionnaire. The investigators designed the protocol and collected the data, which were analyzed by the University of Milan. The trial, registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02290990), after local EC approval was performed in accordance with the protocol, with the Declaration of Helsinki, with Good Clinical Practice and with local regulations.

Participants

Participants were persons with (pw) MS, pw insomnia (pwINS), and health professionals (HP). General inclusion criteria were: 18–75 years of age. Exclusion criteria were: presence of severe co-morbidities, inability to practice Italian language, and inability to provide informed consent. The specific inclusion criteria were MS diagnosis and 1 month relapse free in pwMS [21], diagnosis of insomnia in pwINS [22], working at Niguarda Hospital, regardless of the job role, in HP.

Intervention

IID was delivered by a single skilled psychotherapist through eight weekly training group sessions in 2 months. Each session lasted 60 min and involved eight people, homogeneous for condition. Heart rate and pulse ox were recorded pre- and post-session. IID training consists of four practical steps, twice repeated: a selection of Jacobson relaxation exercises with breath awareness, motor imaging, body imaginative scan, imaginative experience. In each session, after the practice, the participants were invited to a group discussion, managed by the psychotherapist. Participants were invited to repeat the IID steps at home.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was the post intervention change of fatigue (2 months), measured with Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS) [23]. Secondary outcomes were the change of insomnia, stress and QoL, respectively evaluated with Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Rapid Stress Assessment (VRS), and MS Quality of life-54 (MSQOL-54) [24–26]. The questionnaires were self-administered and identified by a personal secret code.

Sample Size

The sample size was calculated on available MS literature data [27]. Assuming an MFIS baseline score of approximately 13 ± 4 and anticipating a change after intervention of approximately 4 units with correlation among repeated measures ≤0.6, a total sample of 144 subjects (24 subjects per intervention/condition group) had a power ≥90% to detect with alpha error ≤0.025 an effect of the intervention explaining at least 12.5% of the total variance. In case of violation of the ANOVA assumptions, a Wilcoxon test for repeated measures would have had a power of 85%.

Statistical Analysis

The data have been described as central tendency with 95% confidence interval, stratified by condition and time of observation.

Baseline comparison of normally distributed variables were performed with the univariate ANOVA, using as factors condition and group of randomization. The primary endpoint, consisting in the fatigue change between pre- and post-intervention, was analyzed as a change at 2 months vs. baseline, compared between randomization groups with the univariate ANOVA using condition and observation as factors and baseline value as covariate. Missing changes due to blank questionnaires were set to zero. This procedure yields, for two measures, the same results as the repeated measures analysis. The overall time trend was analyzed with the general linear models for repeated measures, using condition and observation as factors, and baseline value as covariate. Potential confounders were included in the model and missing questionnaire answers were replaced with the last observation carried forward procedure. Point comparisons of continuous variables between exposure groups were performed by condition with the Welch–Satterthwaite modification of the t test.

Distribution of nominal variables at baseline was compared between randomization groups by condition with the Chi square test. Changes over time were tested with the Chi square test. Point comparisons of ordinal variables were performed with the Wilcoxon or Mann–Whitney or Friedman test. Analyses were performed with SPSS version 17 integrated with sections in R [28]. Results with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Study Conduction

Enrollment

The study was performed between September 2014–September 2015. Enrollment took place at Niguarda Hospital, Milan, Italy. Outpatients afferent to the specialized MS and Sleep Disorders Centres had been informed about the study through an unselective proposal by the neurologist who was able to verify the criteria for inclusion/exclusion. HP had been informed about the trial by an intranet announcement. Interested subjects signed the informed consent and filled out the baseline questionnaires.

Intervention Procedure

After the baseline visit for the questionnaires compilation, the study coordinator communicated the allocation of each participant. Nine intervention subgroups of eight people, homogeneous for condition (SM, insomnia, health profession), were scheduled. The participants attended to the eight weekly sessions guided by the psychotherapist to complete the IID training. For the controls, IID was planned 9 months later, after the end of follow-up.

Surveillance and Follow-up

At baseline, participants filled out all the questionnaires; the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) was assessed and the Brief International Cognitive Assessment for Multiple Sclerosis (BICAMS) was collected in pwMS and re-scored at 5 months [29, 30]. After IID therapy, three control visits were planned at 2–5–8 months from training onset to fill out the questionnaires and three month later for a satisfaction questionnaire.

Results

Participants

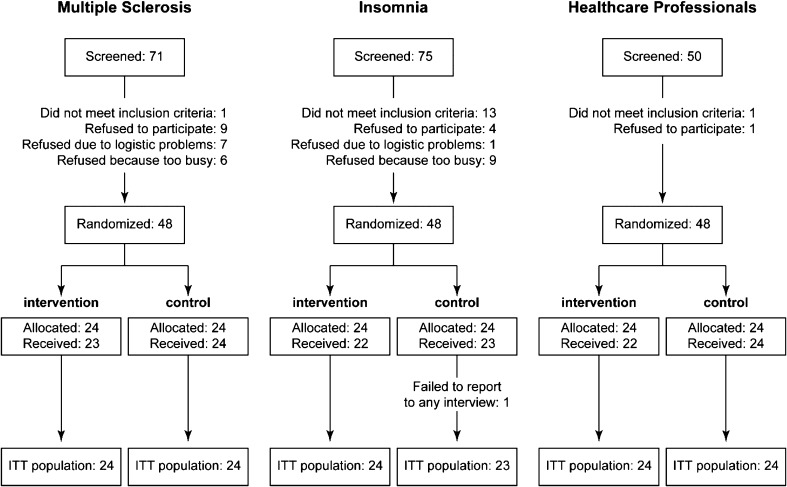

One hundred and ninety-six cases were screened: 71 pwMS, 75 pwINS, and 50 HP; 15 people did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 37 declined to participate. Forty-eight cases for each group were enrolled, and the total number of participants was 144 (Fig. 2). Baseline clinical features are reported in Tables 1 (pwMS) and 2 (pwINS). Disease duration and severity were homogeneous between treated and controls within each condition. The median age of HP was 50 years (range 27–61) and the job duration 20 years (1–38).

Fig. 2.

Enrollment and randomization

Table 1.

PwMS baseline data

| Exposed (N = 24) | Controls (N = 24) | Total (N = 48) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease type | ||||

| PP | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.2%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.235a |

| RR | 20 (83.3%) | 22 (91.7%) | 42 (87.5%) | |

| SP | 4 (16.7%) | 1 (4.2%) | 5 (10.4%) | |

| Years from onset | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 10.5 ± 8.2 | 16.1 ± 11.1 | 13.3 ± 10.1 | 0.054b |

| Median [range] | 9 [0, 27] | 14 [3, 43] | 13 [0, 43] | 0.070c |

| Years from diagnosis | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 8.2 ± 7.3 | 10.5 ± 8.5 | 9.3 ± 7.9 | 0.312b |

| Median [range] | 7 [0, 27] | 9 [0, 33] | 8 [0, 33] | 0.269c |

| EDSS grade prestudy | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 3.15 ± 1.97 | 3.44 ± 2.01 | 3.29 ± 1.97 | 0.666d |

| Median [range] | 2.75 [1.0, 6.5] | 3.50 [0.0, 7.5] | 3.50 [0.0, 7.5] | |

| Therapy pre-study, N (%) | ||||

| None | 6 (25.0%) | 7 (29.2%) | 13 (27.1%) | |

| First line (immunomodulatory) | 15 (62.5%) | 12 (50.0%) | 27 (56.2%) | |

| Second line | 3 (12.5%) | 5 (20.8%) | 8 (16.7%) | |

| Antispastic ± fatigue | 3 (12.5%) | 3 (12.5%) | 6 (12.5%) | |

| Analgesic | 6 (25.0%) | 3 (12.5%) | 9 (18.7%) | |

| Antidepressant ± benzodiazepine | 8 (16.7%) | 6 (25.0%) | 14 (29.2%) | |

aChi square

bWelch–Satterthwaite t test

cMann–Whitney U test

d P from ANOVA, adjusted for sex, age, and years from onset

Table 2.

pwINS baseline

| Exposed (N = 24) | Controls (N = 23) | Total (N = 47) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illness duration (years) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 11.6 ± 12.3 | 19.7 ± 17.9 | 15.6 ± 15.6 | 0.080a |

| Median [range] | 6.2 [0.0, 39.3] | 15.1 [1.1, 55.3] | 9.9 [0, 55.3] | |

| Familiarity for insomnia, N (%)c | ||||

| No | 19 (79.2%) | 13 (59.1%) | 32 (69.6%) | 0.139b |

| Yes | 5 (20.8%) | 9 (40.9%) | 14 (30.4%) | |

| Sleep hygiene in use, N (%) | ||||

| No | 8 (33.3%) | 10 (43.5%) | 18 (33.3%) | 0.474b |

| Yes | 16 (66.7%) | 13 (56.5%) | 29 (61.7%) | |

| Therapy pre-study, N (%) | ||||

| None | 6 (25.0%) | 2 (8.7%) | 8 (17.0%) | |

| Melatonin ± anxiolytic | 3 (12.5%) | 4 (17.4%) | 7 (14.9%) | |

| Benzodiazepines | 9 (37.5%) | 8 (34.8%) | 17 (14.9%) | |

| Antidepressant ± analgesic | 3 (12.5%) | 4 (17.4%) | 7 (14.9%) | |

| Antidepressant + benzodiazepine | 3 (12.5%) | 5 (21.7%) | 8 (17.0%) | |

aWelch–Satterthwaite t test

bChi square test

c1 N/A among control

Outcomes

Significant differences among conditions, reflecting their peculiar discomfort, were detected in the baseline scores (please see Table S1 in the supplementary material for details).

The primary outcome, consisting of fatigue, was evaluated with the MFIS scale score. After IID, the score significantly improved in exposed vs controls, in each out of the three conditions (Table 3).

Table 3.

MFIS scores and 2 months change

| MS | Insomnia | Health professionals |

Global

P |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated (N = 24) | Controls (N = 24) | P | Treated (N = 24) | Controls (N = 23) | P | Treated (N = 24) | Controls (N = 24) | P | ||

| MFIS physical score baseline, mean ± SD | 20.1 ± 9.4 | 20.4 ± 6.7 | 16.2 ± 7.0 | 16.3 ± 8.1 | 15.6 ± 8.6 | 13.0 ± 9.1 | ||||

| MFIS physical score 2 months, mean ± SD | 16.2 ± 9.3 | 20.4 ± 8.1 | 12.9 ± 6.7 | 14.6 ± 5.7 | 11.0 ± 7.1 | 13.0 ± 8.5 | ||||

| MFIS physical score change, mean ± SD | 4.0 ± 5.2 | 0.0 ± 6.7 | 0.018a | 3.3 ± 4.5 | 0.9 ± 4.9 | 0.100a | 4.9 ± 6.2 | 0.0 ± 4.6 | 0.009a | 0.119b |

| MFIS cognitive score baseline, mean ± SD | 16.7 ± 10.0 | 15.4 ± 5.3 | 19.5 ± 7.4 | 20.1 ± 7.4 | 15.5 ± 7.8 | 16.3 ± 7.8 | ||||

| MFIS cognitive score 2 months, mean ± SD | 14.0 ± 8.8 | 15.8 ± 7.7 | 15.0 ± 7.2 | 18.5 ± 5.8 | 10.5 ± 6.5 | 16.0 ± 6.3 | ||||

| MFIS cognitive score change, mean ± SD | 3.2 ± 5.7 | −0.4 ± 5.9 | 0.052a | 4.5 ± 5.7 | 0.9 ± 5.1 | 0.021a | 5.0 ± 7.4 | −0.1 ± 4.9 | 0.001a | 0.443b |

| MFIS total score baseline, mean ± SD | 40.0 ± 19.5 | 39.3 ± 12.0 | 38.9 ± 14.1 | 39.7 ± 14.1 | 33.9 ± 16.2 | 31.7 ± 17.7 | ||||

| MFIS total score 2 months, mean ± SD | 33.0 ± 17.0 | 39.4 ± 16.2 | 30.4 ± 14.0 | 36.7 ± 9.8 | 23.1 ± 13.0 | 31.7 ± 15.7 | ||||

| MFIS total score change, mean ± SD | 7.6 ± 9.3 | −0.1 ± 13.3 | 0.023a | 8.5 ± 9.0 | 1.4 ± 8.7 | 0.007a | 11.1 ± 14.2 | −0.2 ± 9.2 | 0.002a | 0.148b |

a P for the multivariate time-treatment interaction, repeated-measures ANOVA adjusted for baseline value

b P for the effect of condition, ANOVA adjusted for baseline value and exposure to intervention

After treatment, the mean reduction on total 21 items MFIS score among exposed was 7.7 [95% CI 1.1, 14.4] (P = 0.023) in pwMS; 7.1 [1.9, 12.3] (P = 0.007) among pwINS, and 11.3 [4.3, 18.2] (P = 0.002) among HP. No differences among the three conditions were found (P = 0.148). Table S2 in the supplementary material reports additional analyses on proportion of clinically fatigued subjects.

The post intervention fatigue reduction (Table 3) seemed to be more evident for physical than cognitive fatigue in pwMS and this was confirmed up to 8 months (P = 0.039) (Please see Table S3 in the supplementary material).

In pwINS the gain was significant for cognitive fatigue and for the total score; this last maintained up to 8 months of follow-up (P = 0.030) (Please see Table S3 in the supplementary material).

In HP the IID effect was similar in both components of fatigue and was confirmed for the total score (P = 0.007) and for the cognitive score (P = 0.002) at 8 months of follow-up (Please see Table S3 in the supplementary material).

No severe scores or improvement in sleep condition (Table 4) was seen in pwMS (exposed 2.0 ± 4.7; controls 0.8 ± 5.4; P = 0.146). Conversely, the ISI score improved significantly in treated pwINS (4.9 ± 3.0 vs. 1.3 ± 4.0; P = 0.006) and in treated HP (3.3 ± 4.1 vs. −0.1 ± 3.1; P = 0.001) and was also maintained up to 8 months (pwINS P < 0.001; HP P = 0.001) (Please see Table S4 in the supplementary material). Pharmacological therapy was reduced in nine treated subjects vs. four controls and, conversely, it was increased or restored in 2 vs. 5. No adverse events were detected.

Table 4.

ISI score and 2 months change

| ISI score | MS | Insomnia | Health professionals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated (N = 24) | Controls (N = 24) | Treated (N = 24) | Controls (N = 23) | Treated (N = 24) | Controls (N = 24) | |

| Baseline, mean ± SD | 7.4 ± 5.9 | 9.3 ± 5.3 | 18.3 ± 5.5 | 16.8 ± 3.8 | 8.6 ± 6.6 | 9.3 ± 6.9 |

| 2 months, mean ± SD | 5.5 ± 4.2 | 8.5 ± 6.7 | 13.4 ± 5.3 | 14.9 ± 4.7 | 5.2 ± 5.0 | 9.2 ± 7.0 |

| Change, mean ± SD | 2.0 ± 4.7 | 0.8 ± 5.4 | 4.9 ± 3.0 | 1.3 ± 4.0 | 3.3 ± 4.1 | −0.1 ± 3.1 |

| P within conditiona | 0.146a | 0.006a | 0.001a | |||

| P between conditionsb | <0.001b | |||||

a P for the multivariate time-treatment interaction, repeated-measures ANOVA adjusted for baseline value

b P for the effect of condition, ANOVA adjusted for baseline value and exposure to intervention

Discussion

This is the first randomized controlled trial evaluating the usefulness of IID in the treatment of fatigue in three conditions that share discomfort in real daily life. DIMMI SI is a pragmatic study without strict inclusion criteria and, as expected, the baseline clinical features were heterogeneous, although selection bias was mitigated by the randomization with no differences between arms within conditions. IID resulted effective on fatigue in all groups at the end of the intervention, with different impact according to trial assumption and baseline features. In pwMS, the improvement was exclusively associated with the intervention itself, without confounding elements due to changes in sleeping conditions, stress perception or QoL. IID effect was of some relevance, entailing a median improvement of 29% of the baseline value (95% CI 16%, 32%). The physical fatigue continued to show a significant improvement over time. Since pwMS usually experience the body as non-performing and a source of chronic discomfort, this result is particularly relevant to explain IID effect. The treatment could have effectively promoted the improvement of relaxation and spontaneous wellbeing self-research due to better body awareness, rather than cognitive control. At the same time, according to the neurocognitive theory of rehabilitation, the motor imagery exercises could have improved the motor planning [31]. In a rehabilitation approach, the exercise therapy, especially endurance, mixed or mind–body practices, can reduce self reported fatigue [13, 32]. Among others psychological approaches studied for the treatment of MS-related fatigue, cognitive behavioral therapies (CBTs) are focused on problem solving and energy conservation strategies also combined with relaxation or Mindfulness-Based Interventions with the aim of acceptance of unwanted thoughts. CBTs treatments showed a positive short-term effect on fatigue, even if the proposals, the outcomes and the results are still very heterogeneous [17, 32, 33]. We did not find a consistent change of QoL in pwMS, probably due to the high variability of the sample, the dissociation between the two scores [34, 35] or because IID could not help enough to cope with MS. PwINS reported a significant improvement on cognitive fatigue, the highest at baseline. A durable benefit was noticed on sleep as well as on psychological stress and QoL. A reduction of drug use was also observed. The IID effectiveness on sleep was expected based on the relaxation step [36], and the results on fatigue could support that the cognitive fatigue has different basis in MS respect to insomnia. Fatigue improved for HP with a significant benefit on sleep and QoL up to the last follow-up. IID efficacy when fatigue is secondary to insomnia/job conditions could confirm its effect to promote sleep and active coping with psychological distress.

IID proved to be well accepted from all participants, as confirmed by the assiduous participation. Group delivering was preferred to activate empathy, social support and cohesion. The limitations of DIMMI SI trial, being an exploratory study, are the small sample enrolled and the open-label design as blinding to intervention the participants was impossible. The positive effect may be also be related to a performance bias, although active involvement of the control groups was maintained.

Conclusion

DIMMI SI results prompt us to consider IID as a complementary intervention advisable to reduce fatigue in MS and in other stress-related conditions, in health and disease status, in addition to conventional therapies. Taught and administered at first by a skilled psychotherapist, IID can after be self-performed at home. IID can moreover be easily practiced also by persons with physical disability. IID could be considered among the symptomatic treatments for fatigue in MS. Furthermore, IID could be explored as a potential therapy for insomnia. Finally, IID could represent a promising tool to cope with over work symptoms and, hopefully, to increase performance in health care professionals. Anyway, larger studies are needed.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Melania Daolio for study coordination; to Valentina Prone for enrollment; to Valentina Sangalli and Maria Pia Zagaria for cognitive evaluation; to Maria Pia Amato and Benedetta Goretti for BICAMS support. A special thanks to Alessandra Solari for comments and to Neuroradiology and Day Hospital staff for motivation. Our gratitude to all DIMMI SI participants for their active attendance.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Compliance with Ethics Guidleines

The trial, registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02290990), after local EC approval was performed in accordance with the protocol, with the Declaration of Helsinki, with the Good Clinical Practice and with local regulations.

Disclosures

Annalisa Sgoifo, Angelo Bignamini, Loredana La Mantia, Maria G. Celani, Piero Parietti, Maria A. Ceriani, Maria R. Marazzi, Paola Proserpio, Lino Nobili, Alessandra Protti and Elio C. Agostoni have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/C8F8F06014D57B5F.

References

- 1.Giovannoni G. Multiple sclerosis related fatigue. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:2–3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.074948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kluger BM, Krupp LB, Enoka RM. Fatigue and fatigability in neurologic illnesses: proposal for a unified taxonomy. Neurology. 2013;80:409–416. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827f07be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhuri A, Behan BO. Fatigue in neurological disorders. Lancet. 2004;363:978–988. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15794-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veauthier C, Hasselmann H, Gold SM, Paul F. The Berlin Treatment Algorithm: recommendations for tailored innovative therapeutic strategies for multiple sclerosis-related fatigue. EPMA J. 2016;7:25. doi: 10.1186/s13167-016-0073-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudroff T, Kindred JH, Ketelhut NB. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: misconceptions and future research directions. Front Neurol. 2016;7:122. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uccelli MM, Specchia C, Battaglia M, et al. Factors that influence the employment status of people with multiple sclerosis: a multi-national study. J Neurol. 2009;256:1989–1996. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braley TJ, Chervin RD. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: mechanisms, evaluation, and treatment. Sleep. 2010;33:1061–1067. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.8.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandlund C, Westman J, Hetta J. Factors associated with self-reported need for treatment of sleeping difficulties: a survey of the general Swedish population. Sleep Med. 2016;22:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richter K, Acker J, Adam S, Niklewski G. Prevention of fatigue and insomnia in shift workers—a review of non-pharmacological measures. EPMA J. 2016;7:16. doi: 10.1186/s13167-016-0064-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blouin AS, Smith-Miller CA, Harden J, Li Y. Caregiver fatigue: implications for patient and staff safety, part 1. J Nurs Adm. 2016;46:329–335. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas PW, Thomas S, Hillier C, et al. Psychological interventions for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD004431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Senders A, Wahbeh H, Spain R, et al. Mind–body medicine for multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Autoimmun Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/567324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heine M, van de Port I, Rietberg MB, et al. Exercise therapy for fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9:)CD009956. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009956.pub2.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Parietti P. The hypnotic technique. In: DelCorno F, Lang M, editors. Clinical psychology. Individual setting treatments. Milan: Franco Angeli; 1999. pp. 128–157. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brian CC, Niladri KM, Masato N, et al. The power of the mind: the cortex as a critical determinant of muscle strength/weakness. J Neurophysiol. 2014;15:3219–3226. doi: 10.1152/jn.00386.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cichy RM, Heinzle J, Haynes JD. Cerebral imagery and perception share cortical representations of content and location. Cortex. 2012;22:372–380. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simpson R, Booth J, Lawrence M. Mindfulness based interventions in multiple sclerosis—a systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-14-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yadav V, Bowling A, Weinstock-Guttman B, et al. Summary of evidence-based guideline: complementary and alternative medicine in multiple sclerosis: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;82:1083–1092. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neuendorf R, Wahbeh H, Chamine I, Yu J, Hutchison K, Oken BS. The effects of mind–body interventions on sleep quality: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2015;2015:902708. doi: 10.1155/2015/902708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruotsalainen JH, Verbeek JH, Mariné A, et al. Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;CD002892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:292–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Academy of Sleep Medicine . International classification of sleep disorders. 3. Darien: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kos D, Kerckhofs E, Carrea I, et al. Evaluation of the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale in four different European countries. Mult Scler. 2005;11:76–80. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1117oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarsitani L, Biondi M. Development and validation of the VRS, a rating scale for rapid stress assessment. Med Psicosom. 1999;44:163–177. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solari A, Filippini G, Mendozzi L, et al. Validation of Italian multiple sclerosis quality of life 54 questionnaire. J Neurol Neurosurg Psichiatry. 1999;67:158–162. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.2.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moss-Morris R, McCrone P, Yardley L, et al. A pilot randomised controlled trial of an Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy self-management programme (MS Invigor8) for multiple sclerosis fatigue. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50:415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 17.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc. Released 2008.

- 29.Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS) Neurology. 1983;33:1444–1452. doi: 10.1212/WNL.33.11.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goretti B, Niccolai C, Hakiki B, et al. The brief international cognitive assessment for multiple sclerosis (BICAMS): normative values with gender, age and education corrections in the Italian population. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:171. doi: 10.1186/s12883-014-0171-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Catalan M, De Michiel A, Bratina A, et al. Treatment of fatigue in multiple sclerosis patients: a neurocognitive approach. Rehabil Res and Pract. 2011; Article ID 670537, 5 pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Khan F, Amatya B, Galea M. Management of fatigue in persons with multiple sclerosis. Front Neurol. 2014;5:177. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van den Akker LE, Beckerman H, Collette EH, Eijssen IC, Dekker J, de Groot V. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2016;90:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollmann W, Busch C, Voltz R. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Measures, relevance, problems, and perspectives. Nervenarzt. 2005;76:154–169. doi: 10.1007/s00115-004-1790-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Etemadifar M, Sayahi F, Alroughani R, et al. Effects of prolonged fasting on fatigue and quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2016;37:929–933. doi: 10.1007/s10072-016-2518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgenthaler T, Kramer M, Alessi C, Friedman L, et al. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: an update. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep. 2006;29:1415–1419. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.9.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.