Abstract

Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides (2D TMDs) have gained great interest due to their unique tunable bandgap as a function of the number of layers. Especially, single-layer tungsten disulfides (WS2) is a direct band gap semiconductor with a gap of 2.1 eV featuring strong photoluminescence and large exciton binding energy. Although synthesis of MoS2 and their layer dependent properties have been studied rigorously, little attention has been paid to the formation of single-layer WS2 and its layer dependent properties. Here we report the scalable synthesis of uniform single-layer WS2 film by a two-step chemical vapor deposition (CVD) method followed by a laser thinning process. The PL intensity increases six-fold, while the PL peak shifts from 1.92 eV to 1.97 eV during the laser thinning from few-layers to single-layer. We find from the analysis of exciton complexes that both a neutral exciton and a trion increases with decreasing WS2 film thickness; however, the neutral exciton is predominant in single-layer WS2. The binding energies of trion and biexciton for single-layer WS2 are experimentally characterized at 35 meV and 60 meV, respectively. The tunable optical properties by precise control of WS2 layers could empower a great deal of flexibility in designing atomically thin optoelectronic devices.

Introduction

Atomic layer two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides (2D TMDs) have garnered many interests for their unique electrical and optical properties including excellent electron mobility, high photoluminescence, semiconductor at atomic scale, and tunable band gap1–3. Recent studies have shown that single-layer TMDs exhibit direct band gap property that is accompanied by strong photoluminescence (PL) emission and large exciton binding energy; thus, they are promising materials for fundamental studies as well as next-generation ultra-thin opto-electronic devices4,5. Among the 2D TMDs, most researches have focused on MoS2 in hopes of finding new properties and potential applications; however, little attention has been paid to WS2. Single-layer WS2 has a direct band gap of 2.1 eV6 and a strong quantum yield of ~6% (single-layer MoS2 yields ~0.1%)7, whereas few-layer WS2 is an indirect band gap semiconductor with a bandgap of 1.35eV8. Few attempts have been made to synthesize large scale single-layer WS2 film. Song et al.9 presented fabrication of layer-controlled WS2 by sulfurization of WO3 film using atomic layer deposition (ALD), and Yun et al.10 reported centimeter-scale single-layer WS2 on gold foil by using chemical vapor deposition (CVD). However, their PL spectra within the single-layer WS2 film were spatially nonuniform. In our previous report11, we demonstrated centimeter scale WS2 film by the two-step process of tungsten deposition followed by sulfurization in a low-pressure CVD. Despite the successful synthesis of the large scale WS2 film, the film exhibits both single- and few-layer of WS2; also, the single-layer WS2 does not show uniformity. Thus, several post-treatment approaches were attempted to control the number of layers for any 2D TMDs. For example, Castellanos-Gomez et al.12 reported the thinning of expoliated few-layer MoS2 film down to a single-layer by using a focused laser beam. Venkatakrishnan et al.13 reported a laser thinning of WS2 flake down to single-layer with revealing improvement of the fluorescence emission intensity and micro-encryption by surface modification. Ni et al.14 used a plasma technique for layer by layer etching of mechanically exfoliated MoS2 film; however, this technique requires physical mask for selective etching on TMDs film. No systematic study for fabrication of uniform single-layer WS2 and its related opto-electronic properties have been reported.

One of the peculiar features of single-layer TMDs is strong excitonic effect caused by their absence of interlayer coupling and the lack of inversion symmetry, which mostly account for the interesting PL emission property15,16. The excitons are generated by electron-hole pairs in a single-layer TMDs that has the large binding energies ranging from 0.3 to 1.0 eV, which is attributed to their strong Coulomb attraction between charged particles17,18. In particular, photoexcitation in 2D TMDs leads to the formation of multi-carrier bound states because excitons can interact with free electrons19,20. Such interaction forms the exciton complexes including trions, a localized excitons consists of three charged quasiparticles (e.g., a negative trion consists of two electrons and one hole and a positive trion consists of two holes and one electron). The interaction of charged carriers and excitons controls the optical properties of TMDs21. Hence, the first step is to understand the behavior of exciton complexes in WS2 for practical applications in opto-electronic devices as well as for the fundamental physics of emergent new materials. Furthermore, the exact values for the binding energy of the excitons in WS2 are still debated and the behavior of exciton complexes with respect to the WS2 layers remains unexplored.

In this regard, we have employed high-power laser processing to fabricate a uniform single-layer WS2 from the few-layer WS2 synthesized by a scalable two-step CVD method. Atomically uniform single-layer WS2 was successfully synthesized by the two-step CVD method followed by a laser thinning method. The behavior of exciton complexes with the number of WS2 layer was investigated during the laser thinning process. We found that the PL intensity has increased linearly (up to 6 times higher) as the number of WS2 layer decreased. In particular, the dominant exciton in single-layer WS2 is neutral exciton, while trion is dominant in few-layer WS2 as analyzed by PL spectrum. These changes of exciton intensity contribute largely to the PL spectra of WS2 film; such phenomenon is invaluable to engineer the opto-electronic properties of 2D WS2.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of few-layer WS2

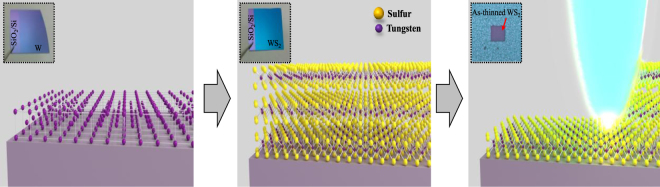

The synthesis of uniform few atomic layer 2D TMDs was presented in our previous report by the two-step method1,22. Here we introduce a large-scale single-layer WS2 film synthesis by using the two-step method followed by a laser thinning process. Schematic of the overall process and optical images of the sample in each step are presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Schematics illustrating the two-step method for few-layer WS2 film growth and the laser thinning process for single-layer WS2 fabrication (Insets show the optical images of as-deposited W film, WS2 film after sulfurization of W film, and laser thinned WS2 film on SiO2/Si substrate).

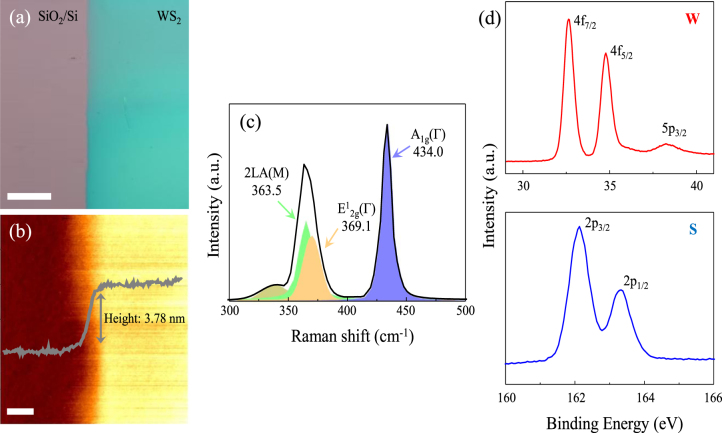

The synthesized WS2 film was characterized by AFM, Raman spectroscopy, PL, and XPS. The optical image of as-synthesized few-layer WS2 film on a SiO2/Si substrate indicates uniform and large-scale growth of WS2 film (Fig. 2a). The thickness of WS2 film is estimated to be ~3.78 nm (Fig. 2b), which is 4–5 layers of WS2, as confirmed by the AFM in the previous studies6,23. Figure 2c presents the Raman spectrum of as-synthesized few-layer WS2 film (measured at 514 nm excitation laser line). The Raman spectrum is governed by the first-order modes: E1 2g (Г) at 369.1 cm−1 and A1g (Г) at 434.0 cm−1; however, the intensity of the second order mode of 2LA (M) at 363.5 cm−1 is also very high for WS2. Even though the 2LA (M) mode is overlapped with the E1 2g mode, the peak is separated their individual contributions by the Lorentzian fitting. The frequency difference (△k) between 2LA (M) and A1g as well as E1 2g and A1g modes are 70.5 cm−1 and 64.9 cm−1, respectively. Thus, it is confirmed that the as-synthesized film is 4–5 layers of WS2 6,24. We also characterized the WS2 film using XPS (Fig. 2d). The 4 f core-level spectrum represents three peaks at 32.6, 34.8, 38.2 eV corresponding to the W 4f7/2, W 4f5/2, and W 5p3/2 state, respectively. The S 2p core-level shows two peaks at 162.1 and 163.3 eV, which match with the S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2 states, respectively. Based on the XPS data, an excellent stoichiometry of the atomic WS2 film is realized by the calculated S (66.7%) to W (33.3%) ratio of 225.

Figure 2.

(a) Optical image of the few-layer WS2 film on SiO2/Si substrate. Scale bar: 100 μm. (b) Height profile and image of the WS2 film (Scale bar: 5 μm). (c) Raman spectrum of the WS2 film using the 514 nm laser excitation and its Lorentzian peak fits. (d) XPS data of the W 4 f and S 2p core levels of the WS2 film.

Characterization of single-layer WS2 fabricated by laser thinning method

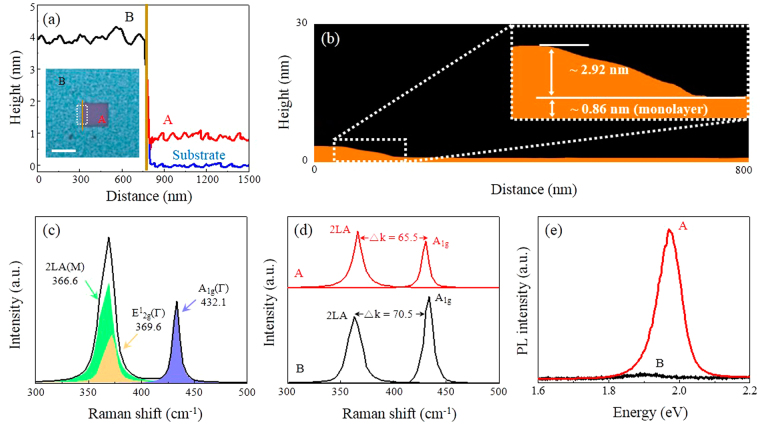

The as-synthesized WS2 film was irradiated by a scanning laser to thin the few-layer WS2 down to a single-layer. Inset of Fig. 3a shows the optical image of WS2 film after laser irradiation for 10 seconds; the image represents the laser covering 5 μm × 5 μm area. Color contrast is observed for the laser irradiated region (A) showing uniform and reduced thickness. The relative thickness difference after the laser irradiation (Fig. 3a) is ~2.88 nm; thus, the thickness of laser irradiation region is ~0.9 nm which corresponds to a single-layer WS2. The detailed surface profile of laser irradiated region is investigated by AFM (Fig. 3b). Remarkably, the laser beam can etch up to ~2.92 nm uniformly over the as-synthesized ~3.78 nm thick WS2 film. It should be noted that the edge of the sidewalls is not flat. This is attributed to the Gaussian intensity profile of the confocal laser. The sidewall could be removed by overlapping the irradiated laser spots. After laser irradiation, Raman and PL measurements were performed with a reduced laser power of 200 μW to the irradiated area of 5 μm × 5 μm (Fig. 3c). The Raman spectra show the 2LA (M), E1 2g (Г), and A1g (Г) modes at 366.6 cm−1, 369.6 cm−1, and 432.1 cm−1, respectively.

Figure 3.

(a) AFM height profile of laser irradiated region (A), non-irradiated region (B), and substrate (ground): the measured thickness between A and B is ~2.88 nm; between the substrate and A is ~0.9 nm (Inset shows the optical image of the laser irradiated area for 15 seconds on 5 × 5 μm, scale bar: 5 μm). (b) An average AFM height profile of the laser irradiated region (A) shows the etched thickness of ~2.92 nm. (c) Raman spectrum of a single-layer WS2 film (A) using the 514 nm laser excitation and its Lorentzian peak fits. (d) Raman spectra showing the peak distance (△k) between 2LA and A1g measuring at 65.5 cm−1 and 70.5 cm−1 for regions A and B, respectively. (e) PL spectra of region A and B showing ~6 times increase of PL emission intensity and ~0.05 eV shift of PL peak position by the laser irradiation.

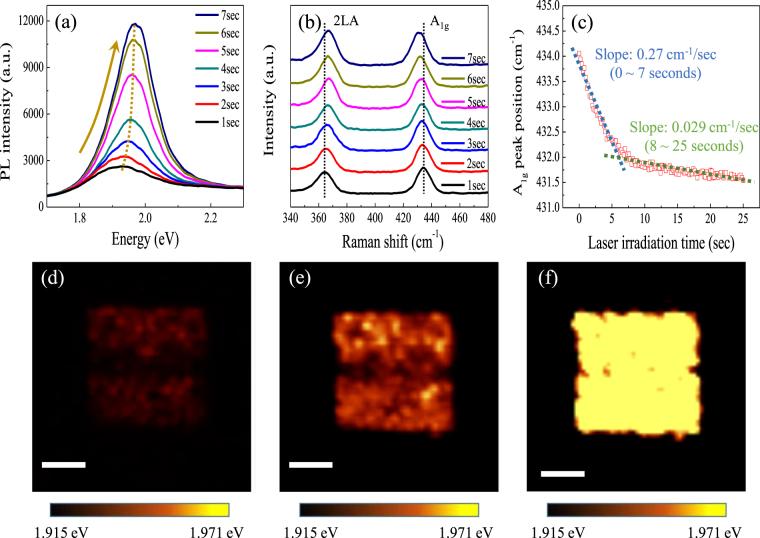

Figure 3d presents the 2LA (M) and A1g modes of both laser irradiated (A) and non-irradiated (B) regions on WS2 film. The frequency differences (△k) between two modes changed from 70.5 cm−1 to 65.5 cm−1; also, the relative intensity of I 2LA/I A1g increased from 0.77 to 1.1. Berkdemir et al.6 reported that frequency differences (△k) and the intensity ratios investigated by Raman spectra (λexc = 514 nm) for thin WS2 film are modifiable by the number of layers. Particularly, single-layer WS2 shows △k of 65.2 cm−1 and I 2LA/I A1g of 2.1; those values are slightly different from the results of our single-layer WS2 fabricated by laser irradiation. The differences are attributed to the unetched few-layer WS2 as illustrated in the height profile (Fig. 3b). Figure 3e indicates PL intensities for both regions A (laser-irradiated) and B (non-irradiated) in Fig. 3a. After laser irradiation, PL intensity increases substantially up to 6 times; in addition, the PL peak position is shifted from 1.92 eV to 1.97 eV. The 1.97 eV PL peak position corresponds to single-layer WS2 26,27. Based on this approach, wafer scale laser-thinned single-layer WS2 film could be readily fabricated by using a scanning laser beam irradiation. We employed in situ confocal PL and Raman spectroscopy to investigate the variation in the PL and Raman spectra with respect to the laser irradiation time. Figure 4a depicts the PL spectra of the WS2 film measured with laser irradiation times (from 0 to 7 seconds) under ambient conditions. The PL intensity increases steadily as a function of the laser irradiation time of up to 7 seconds in which the PL intensity reaches maximum; as a result, the PL peak position is shifted from 1.92 eV to 1.97 eV, (dotted line in Fig. 4a). Thus, the precise thinning of the as-synthesized few-layer WS2 film by the laser irradiation is evidenced by the increase in PL peak intensity and the shift in position. Figure 4b indicates Raman spectra of WS2 film recorded at different laser irradiation time. The relative intensity (I 2LA/I A1g) is gradually changed from 0.8 for 1 second to 1.1 for 7 seconds; also, the frequency difference between 2LA (M) and A1g (Г) modes is reduced to 65.5 cm−1 for 7 seconds of irradiation time. The constant change of PL and Raman spectra with laser irradiation time reveals that the few-layer WS2 film is continuously thinned with the laser time. The Raman peak position shift in A1g mode shows an interesting phenomenon with regard to self-limited etching behavior. Figure 4c shows the A1g mode shift as a function of laser irradiation time (from 0 to 25 seconds). It is noted that there exist two regimes: the region exposed for 0–7 seconds shows larger slope than the region exposed for 8–25 seconds. As a result, it is expected that the top WS2 layers are etched entirely by the laser irradiation of 7 seconds, whereas the bottom single-layer WS2 remains unetched even after 7 seconds laser irradiation. The lower slope of the A1g mode after 7 seconds is attributed to the local strains or disorders caused by the continuous laser irradiation28,29. PL and Raman spectra (Fig. 4a and b) verify that the single-layer WS2 film is already achieved after laser irradiation for 7 seconds; thus, the etching rate of WS2 film is ~0.42 nm/sec calculated by etched thickness (2.92 nm in Fig. 3b) and laser irradiation time (7 seconds).

Figure 4.

(a) PL and (b) Raman spectra as a function of the laser irradiation time from 1 to 7 seconds. (c) Raman frequencies recorded at various laser irradiation time (from 1 to 25 seconds) for A1g mode. PL peak position map of the laser irradiated area of 5 μm × 5 μm after (d) 2 seconds, (e) 5 seconds, and (f) 10 seconds of laser irradiation. Scale bar: 2 μm.

To demonstrate the fabrication of single-layer WS2 film with high uniformity, PL mapping with a PL peak position is carried out on the laser irradiated area (Fig. 4d–f). It is observed that the PL peak variation is uneven for 2 and 5 second irradiation time. However, the spatial uniformity increases significantly after laser irradiation for 10 seconds as shown in Fig. 4f. This uniform PL peak position demonstrates that the formation of uniform single-layer WS2 film was achieved by the laser irradiation; also, further undesirable damage after forming the single-layer WS2 film was prevented30. Once the normally incident laser is absorbed on WS2 layers, the WS2 layers produce local heating on the plane. Gastellanos-Gomez et al.12 reported that the generated thermal energy mostly dissipate through the planer direction to the TMDs layers rather than the perpendicular direction which is bonded by weak van der Waals forces. Similarly, as reported by Han et al.30, the generated heat by light absorption is mainly accumulated on the upper graphene layers when a laser is induced on the film, while the SiO2/Si substrate plays an important role as a heat reservoir for the single-layer graphene to remain unetched. It is also reported that the heat conduction across 2D crystals-substrate interface is not negligible31. Initially, the heat propagates mostly along the basal plane of WS2 film due to higher thermal conductivity of the basal plane (124 W/mK) than the c-axis of WS2 (1.7 W/mK)32. When the thickness is getting reduced by the laser irradiation, the heat conduction across WS2-SiO2/Si substrate becomes dominant, and the SiO2/Si substrate plays a role as a heat sink. Therefore, the flat and uniform single-layer WS2 film could be produced by laser irradiation.

Investigation on behavior of exciton complexes

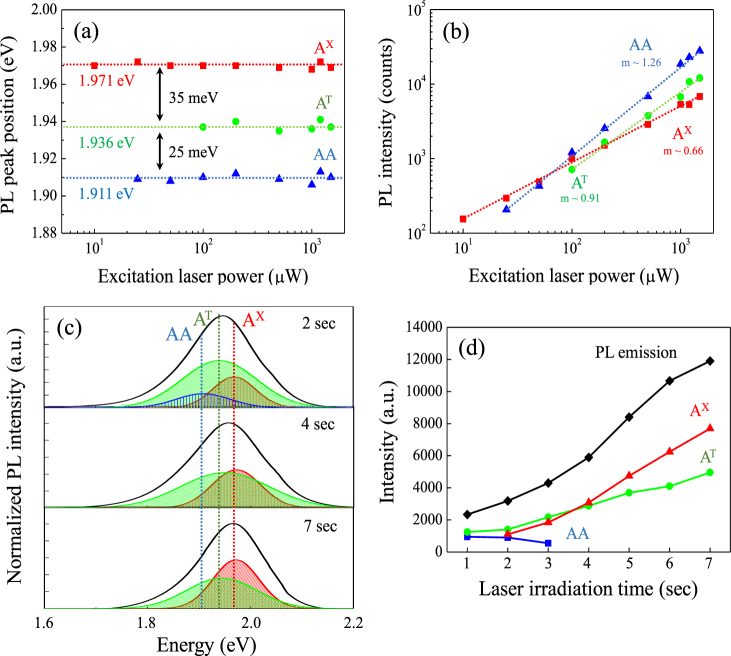

The change of PL spectra was reported to be associated with a transition from indirect band gap (few-layer WS2) to direct band gap (single-layer WS2). Because the origins of variation in relative contributions of exciton complexes (i.e. neutral exciton (AX), trion (AT), and biexciton (AA)) to PL emission have not been studied, we investigate the behavior of the exciton complexes depending on the numbers of WS2 layer. First, we analyze the PL intensities of exciton complexes as a function of laser power to determine the transition and binding energies of the exciton complexes (Fig. 5a and b) as per the definition of the energies21. These plots reveal that the estimated transition energies for AX, AT, and AA are 1.971, 1.936, and 1.911, respectively; also, the binding energies for AT, and AA are 35 meV and 60 meV, respectively. Those binding energies are consistent with the computationally simulated results of WS2 33–35. Each excitons indicates different values of slope (m) regarding the increase of PL intensity with respect to laser power (Fig. 5b). Based on previous studies, the exponent of m = 1.2–1.9 is a typical value for AA36,37; in other words, AA has super-linear slopes because of the kinetics of excitation recombination and formation38. It is also important to note that there is an indication for the exponent of the AX (m ~0.66) is half the value of the AA (m ~1.26)39. Therefore, the sub-linear values of m ~0.66 and m ~0.91 for AX and AT, respectively, and the super-linear value of m ~1.26 for AA can verify the types of exciton for WS2 40. Figure 5c and d indicates the PL spectra obtained from representative irradiation times of 1–7 seconds by decomposing them into AX, AT, and AA. For the increased laser irradiation of up to 7 seconds, the predominant exciton of the PL spectrum is changed from AT to AX (Fig. 5c). It is noted that the steady intensity of AA disappeared at 3 seconds of irradiation time; thus, only AT and AX affects the PL spectra of laser thinned WS2 film, whereas both AT and AX increase as the number of WS2 layers decrease by the longer laser irradiation time. The increased rate in the intensity of AX is higher than AT (Fig. 5d); therefore, the PL spectrum is shifted up to 1.97 eV for the single-layer.

Figure 5.

Laser power dependent PL (a) peak positions and (b) intensities of exciton complexes from the laser irradiated single-layer WS2. The m values indicate logarithmic values of each slope, and the dashed lines in (a) and (b) are guides for the eye to visualize. (c) Laser irradiation time dependent photoluminescence spectra and the deconvoluted excitation complexes for 2, 4, and 7 seconds laser irradiation and (d) the overall peak position of exciton complexes with laser irradiation time for1–7 seconds.

We expect that the intensity variation for both AT and AX is affected by the addition of charge carriers (either by an electron or hole) absorbed by oxygen molecule during laser irradiation; also, it is assumed that the variation of charge carriers can directly modify the intensity of both AT and AX 41,42. Oh et al.43 reported the intensity of exciton complexes for single-layer MoS2 with various laser irradiation time under ambient conditions; here, the intensity of AX increases dramatically in the first few minutes of laser irradiation due to the charge transfer of MoS2 to the adsorbed oxygen group induced by laser irradiation. Another report also presented a single-layer MoS2 treated by oxygen plasma that shows much improved PL spectrum because of the charge transfer from MoS2 to oxygen molecule on the sulfur vacancy44.

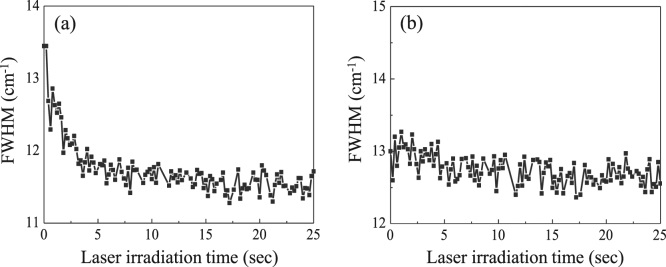

To confirm the charge transfer effect, full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the A1g mode is measured with laser irradiation time (0–25 seconds) (Fig. 6a). The reduced FWHM of the A1g mode during the WS2 film thinning is the evidence of p-doping (electron is moved from WS2 to oxygen molecule)45; otherwise, FWHM of the E1 2g mode is not widely variable as a function of laser irradiation time (Fig. 6b). Therefore, the charge transfer from WS2 to oxygen molecule induced by laser irradiation contributes to the increased ratio of AX to AT with the thinning of WS2. Interestingly, we observed the blue-shift of ~50 meV for the exciton peak as the thickness is reduced from few- to single-layer (Fig. 5c). Based on the previous experimental and theoretical studies, the quasiparticle band gap in 2D WS2 is expected to increase with thinning of 2D WS2; also, the binding energy of exciton complexes is predicted to increase with the thinning of WS2 film due to the enhanced electron-hole interaction by weak dielectric screening46–50. The increase in quasiparticle band gap and the exciton binding energy affects the exciton peak position; thus, the shift of exciton complexes is negligible with the decreasing number of WS2 layer. The blue-shifting of the exciton peak (measured ~50 meV) during the laser thinning process is consistent with the previous report15.

Figure 6.

The full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of (a) A1g mode and (b) E1 2g mode of WS2 as a function of the laser irradiation time (1–25 seconds).

Discussion

Precise control of WS2 layers is achieved by using two-step CVD synthesis method followed by a laser-thinning. The scalable synthesis of uniform single-layer WS2 film is confirmed by AFM thickness measurement (~0.9 nm), Raman frequencies difference (65.5 cm−1), and PL peak position (1.97 eV). Based on the variation of PL and Raman spectra with respect to laser irradiation time, the optimum laser irradiation time for the synthesis of a single-layer WS2 film is found to be 7 seconds. It is also realized that the single-layer WS2 is retained with additional laser irradiation time, which is attributed to the thermal energy dissipated through the substrate. The intensity of both neutral exciton and trion increases with the reduction of WS2 thickness; however, the biexciton appears to have no noticeable change. In particular, dominant exciton component in PL spectrum for the few-layer and single-layer WS2 is trion and neutral exciton, respectively. The observed binding energies of the exciton complexes for single-layer WS2 are 35 meV (trion) and 60 meV (biexciton). The tunable optical properties by precise control of WS2 layers and the understanding of their exciton complexes would lead to the design of novel optoelectronic devices.

Methods

Preparation of wafer scale thin WS2 film

Large-scale few-layer WS2 film was synthesized on a p-type silicon substrate (Boron doped; 0.001–0.005 Ω·cm) with 300 nm thick SiO2 by using two-step method involving magnetron sputtering for deposition of tungsten (W) film and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) for sulfurization of W film. For the first step, 99.99% purity W target (Plasmaterials) was used to deposit thin film of W. Sputtering W film was carried out for 10 seconds at room temperature. Subsequently, the W film was sulfurized in the CVD for 1 hour at 600 °C to transform the film into WS2. During sulfurization, the sulfur powder was heated separately at ~250 °C, and argon was used as a carrier gas to convey sulfur (S) vapor species toward the W films.

Characterization of the WS2 film

Thickness and surface analysis of as-synthesized WS2 film were performed by atomic force microscopy (AFM) (Parks system, NX-10 model). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Thermo Scientific, ESCALAB250 model) was used for the chemical binding energies of W and S orbitals. A lab-made spectrometer combined with 514 nm wavelength and 200 μW power of a solid-state confocal laser microscope was used for PL and Raman spectroscopy measurements40,51. A 0.9 NA objective was used to focus the laser light which the lateral resolution was set at approximately 300 nm. Scattered light was gathered by the 0.9 NA objective and directed to a 50 cm long monochromater equipped with a cooled CCD.

Condition of laser thinning process

A scanning laser from a lab-made spectroscope (laser wavelength of 514 nm with 2.5 mW power and 300 nm lateral resolution) was used to thin few-layer WS2 film down to single-layer by moving the laser over the WS2 film laterally by 300 nm for the next exposure. The total number of exposures is 256 times for 5 × 5 μm area, and the exposure time is 15 seconds for each laser irradiation. For a detailed study of exciton complexes variation depending on layer numbers, we used the same laser with increased laser exposure time from 0 to 25.6 seconds and measured the individual PL spectrum per each 0.2 second (total 128 measurements) under ambient conditions.

Acknowledgements

J.K. acknowledges financial support from the Institute for Basic Science (IBS-R011-D1). W.C. acknowledges partial support from the UNT SEED fund.

Author Contributions

J.P. performed the synthesis of WS2 film and chrcaterizations. J.P. and W.C. wrote the manuscrip. M.K. worked on PL measurement and exciton complexes analysis. E.C. conducted device fabrication and prepared figures. J.K. and W.C. contributed to the overall guidance, data analysis and manuscript editing. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Juhong Park and Min Su Kim contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jeongyong Kim, Email: j.kim@skku.edu.

Wonbong Choi, Email: Wonbong.Choi@unt.edu.

References

- 1.Park J, et al. Thickness modulated MoS2 grown by chemical vapor deposition for transparent and flexible electronic devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015;106:012104. doi: 10.1063/1.4905476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang QH, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kis A, Coleman JN, Strano MS. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012;7:699–712. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang R, et al. Third-harmonic generation in ultrathin films of MoS2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2013;6:314–318. doi: 10.1021/am4042542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mak KF, Lee C, Hone J, Shan J, Heinz TF. Atomically thin MoS2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010;105:136805. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.136805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Splendiani A, et al. Emerging photoluminescence in monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 2010;10:1271–1275. doi: 10.1021/nl903868w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkdemir, A. et al. Identification of individual and few layers of WS2 using Raman Spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 3 (2013).

- 7.Yuan L, Huang L. Exciton dynamics and annihilation in WS2 2D semiconductors. Nanoscale. 2015;7:7402–7408. doi: 10.1039/C5NR00383K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuc A, Zibouche N, Heine T. Influence of quantum confinement on the electronic structure of the transition metal sulfide T S 2. Phys. Rev. B. 2011;83:245213. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.83.245213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song J-G, et al. Layer-controlled, wafer-scale, and conformal synthesis of tungsten disulfide nanosheets using atomic layer deposition. ACS nano. 2013;7:11333–11340. doi: 10.1021/nn405194e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yun SJ, et al. Synthesis of centimeter-scale monolayer tungsten disulfide film on gold foils. ACS nano. 2015;9:5510–5519. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b01529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choudhary, N. et al. Centimeter Scale Patterned Growth of Vertically Stacked Few Layer Only 2D MoS2/WS2 van der Waals Heterostructure. Sci. Rep. 6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Castellanos-Gomez A, et al. Laser-thinning of MoS2: on demand generation of a single-layer semiconductor. Nano Lett. 2012;12:3187–3192. doi: 10.1021/nl301164v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venkatakrishnan A, et al. Microsteganography on WS2 monolayers tailored by direct laser painting. ACS nano. 2017;11:713–720. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b07118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y, et al. Layer-by-layer thinning of MoS2 by plasma. ACS nano. 2013;7:4202–4209. doi: 10.1021/nn400644t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chernikov A, et al. Exciton binding energy and nonhydrogenic Rydberg series in monolayer WS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014;113:076802. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.076802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye Z, et al. Probing excitonic dark states in single-layer tungsten disulphide. Nature. 2014;513:214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature13734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thilagam A. Exciton complexes in low dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. J. Appl. Phys. 2014;116:053523. doi: 10.1063/1.4892488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang DK, Kidd DW, Varga K. Excited Biexcitons in Transition Metal Dichalcogenides. Nano Lett. 2015;15:7002–7005. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b03009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pospischil A, Mueller T. Optoelectronic Devices Based on Atomically Thin Transition Metal Dichalcogenides. Applied Sciences. 2016;6:78. doi: 10.3390/app6030078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velizhanin KA, Saxena A. Excitonic effects in two-dimensional semiconductors: Path integral Monte Carlo approach. Phys. Rev. B. 2015;92:195305. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.92.195305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee HS, Kim MS, Kim H, Lee YH. Identifying multiexcitons in MoS2 monolayers at room temperature. Phys. Rev. B. 2016;93:140409. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.93.140409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choudhary N, Park J, Hwang JY, Choi W. Growth of large-scale and thickness-modulated MoS2 nanosheets. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;6:21215–21222. doi: 10.1021/am506198b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, et al. Chemical vapor deposition of monolayer WS2 nanosheets on Au foils toward direct application in hydrogen evolution. Nano research. 2015;8:2881–2890. doi: 10.1007/s12274-015-0793-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iqbal, M. Z., Iqbal, M. W., Siddique, S., Khan, M. F. & Ramay, S. M. Room temperature spin valve effect in NiFe/WS2/Co junctions. Sci. Rep. 6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Park J, et al. Layer-modulated synthesis of uniform tungsten disulfide nanosheet using gas-phase precursors. Nanoscale. 2015;7:1308–1313. doi: 10.1039/C4NR04292A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao W, et al. Evolution of electronic structure in atomically thin sheets of WS2 and WSe2. ACS nano. 2012;7:791–797. doi: 10.1021/nn305275h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gutiérrez HR, et al. Extraordinary room-temperature photoluminescence in triangular WS2 monolayers. Nano Lett. 2012;13:3447–3454. doi: 10.1021/nl3026357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang, L. et al. Lattice strain effects on the optical properties of MoS2 nanosheets. Sci. Rep. 4 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Sun L, et al. Plasma modified MoS2 nanoflakes for surface enhanced Raman scattering. Small. 2014;10:1090–1095. doi: 10.1002/smll.201300798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han GH, et al. Laser thinning for monolayer graphene formation: heat sink and interference effect. Acs Nano. 2010;5:263–268. doi: 10.1021/nn1026438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mak KF, Lui CH, Heinz TF. Measurement of the thermal conductance of the graphene/SiO2 interface. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010;97:221904. doi: 10.1063/1.3511537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pisoni A, et al. Anisotropic transport properties of tungsten disulfide. Scripta Materialia. 2016;114:48–50. doi: 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2015.11.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kylänpää I, Komsa H-P. Binding energies of exciton complexes in transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers and effect of dielectric environment. Phys. Rev. B. 2015;92:205418. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.92.205418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peimyoo N, et al. Nonblinking, intense two-dimensional light emitter: monolayer WS2 triangles. ACS nano. 2013;7:10985–10994. doi: 10.1021/nn4046002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitioglu A, et al. Optical manipulation of the exciton charge state in single-layer tungsten disulfide. Phys. Rev. B. 2013;88:245403. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.88.245403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Birkedal D, Singh J, Lyssenko V, Erland J, Hvam JM. Binding of quasi-two-dimensional biexcitons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;76:672. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phillips R, Lovering D, Denton G, Smith G. Biexciton creation and recombination in a GaAs quantum well. Phys. Rev. B. 1992;45:4308. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.45.4308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.You Y, et al. Observation of biexcitons in monolayer WSe2. Nat. Phys. 2015;11:477–481. doi: 10.1038/nphys3324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shang J, et al. Observation of excitonic fine structure in a 2D transition-metal dichalcogenide semiconductor. ACS nano. 2015;9:647–655. doi: 10.1021/nn5059908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim MS, et al. Biexciton Emission from Edges and Grain Boundaries of Triangular WS2 Monolayers. ACS nano. 2016;10:2399–2405. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu, P. et al. Control of Radiative Exciton Recombination by Charge Transfer Induced Surface Dipoles in MoS2 and WS2 Monolayers. Sci. Rep. 6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Mouri S, Miyauchi Y, Matsuda K. Tunable photoluminescence of monolayer MoS2 via chemical doping. Nano Lett. 2013;13:5944–5948. doi: 10.1021/nl403036h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oh HM, et al. Photochemical Reaction in Monolayer MoS2 via Correlated Photoluminescence, Raman Spectroscopy, and Atomic Force Microscopy. ACS nano. 2016;10:5230–5236. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b00895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nan H, et al. Strong photoluminescence enhancement of MoS2 through defect engineering and oxygen bonding. ACS nano. 2014;8:5738–5745. doi: 10.1021/nn500532f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chakraborty B, et al. Symmetry-dependent phonon renormalization in monolayer MoS2 transistor. Phys. Rev. B. 2012;85:161403. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.85.161403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keldysh L. Coulomb interaction in thin semiconductor and semimetal films. Soviet Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Physics Letters. 1979;29:658. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hanamura E, Nagaosa N, Kumagai M, Takagahara T. Quantum wells with enhanced exciton effects and optical non-linearity. Materials Science and Engineering: B. 1988;1:255–258. doi: 10.1016/0921-5107(88)90006-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raja, A. et al. Coulomb engineering of the bandgap in 2D semiconductors. arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.01204 (2017).

- 49.Cudazzo P, Tokatly IV, Rubio A. Dielectric screening in two-dimensional insulators: Implications for excitonic and impurity states in graphane. Phys. Rev. B. 2011;84:085406. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.84.085406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berkelbach TC, Hybertsen MS, Reichman DR. Theory of neutral and charged excitons in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B. 2013;88:045318. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.88.045318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park S, et al. Spectroscopic Visualization of Grain Boundaries of Monolayer Molybdenum Disulfide by Stacking Bilayers. ACS nano. 2015;9:11042–11048. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b04977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]