Abstract

Photosynthetic unicellular organisms, known as microalgae, are key contributors to carbon fixation on Earth. Their biotic interactions with other microbes shape aquatic microbial communities and influence the global photosynthetic capacity. So far, limited information is available on molecular factors that govern these interactions. We show that the bacterium Pseudomonas protegens strongly inhibits the growth and alters the morphology of the biflagellated green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. This antagonistic effect is decreased in a bacterial mutant lacking orfamides, demonstrating that these secreted cyclic lipopeptides play an important role in the algal–bacterial interaction. Using an aequorin Ca2+-reporter assay, we show that orfamide A triggers an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ in C. reinhardtii and causes deflagellation of algal cells. These effects of orfamide A, which are specific to the algal class of Chlorophyceae and appear to target a Ca2+ channel in the plasma membrane, represent a novel biological activity for cyclic lipopeptides.

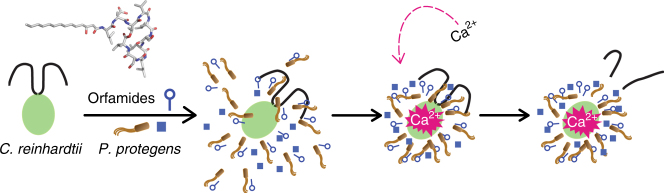

Predatory or competitive interactions between microbes are poorly understood but likely influence global nutrient cycles. Here, the authors show that Pseudomonas bacteria could immobilize algal cells, potential prey, by releasing secondary metabolites that induce a Ca2+ signal and algal deflagellation.

Introduction

Carbon fixation by photosynthetic organisms is a crucial step in the global carbon cycle, converting CO2 and light into valuable, energy-rich organic molecules. Apart from higher plants, prokaryotic and eukaryotic microalgae in aquatic environments are responsible for approximately 50% of all carbon fixation annually1. In addition, these photosynthetic microorganisms are at the base of aquatic food webs, thus playing a key role in diverse ecosystems. In their freshwater and marine habitats, microalgae also naturally coexist with a large variety of other microorganisms. In analogy to the terrestrial plant environment, these complex interactions may influence the fitness and performance of the microalgae and even lead to their death. However, compared to the large body of knowledge on the effects of mutualists or parasites on higher plants2, there is limited information on biotic interactions of photosynthetic microbes. Only recently, an increasing number of studies were reported on the characterization of algicidal bacteria and of natural products or enzymes that directly affect algal fitness3–7. In most cases, diffusible algicidal agents are secreted by the bacteria that inhibit cell growth, disrupt the cell envelope, and/or rapidly lyse target cells7. Other algicidal bacteria require direct contact with the algae to exert their destructive effects. In these cases, they employ enzymes to cleave polysaccharides or proteins that are present on the cell wall of the algae, thereby disrupting cell integrity and causing lysis7. However, most algicidal factors, their effects, and the involved signaling pathways remain to be elusive8. This lack of knowledge is surprising in light of the well-known relevance of microalgae for life on Earth and their emerging importance for biofuel production.

The poor knowledge on the mediators of microalgal–microbial communities may—at least in part—be attributable to the lack of interacting species that are genetically tractable. To evaluate the factors governing the interaction between bacteria and microalgae, we thus focused on a fully sequenced model organism, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, for which molecular tools are available9–11. This biflagellate unicellular green alga is ubiquitously distributed in habitats such as fresh water and moist soil, and has been extensively used to study light perception, photosynthesis, and flagellar function, and also with regard to human diseases9, 12, 13. However, C. reinhardtii is usually grown axenically in the laboratory, and only a few studies have explored how this algal genus responds to changes in biotic factors14–16. Here, we report on the biological function of secondary metabolites from the bacteria Pseudomonas protegens in their interplay with the motile microalga C. reinhardtii. P. protegens (formerly known as P. fluorescens)17 also lives in aquatic and soil environments, where it either promotes plant growth18 or leads to the cell death of the photosynthetic organism3. By means of high-resolution mass spectrometry and a tailor-made reporter system, we found that P. protegens employs chemical mediators, including cyclic lipopeptides to deflagellate the C. reinhardtii cells and alter cytosolic Ca2+ levels. Immobilization and disruption of algal cells by P. protegens and its secondary metabolites appears to provide an advantage to the bacteria when deprived of micronutrients.

Results

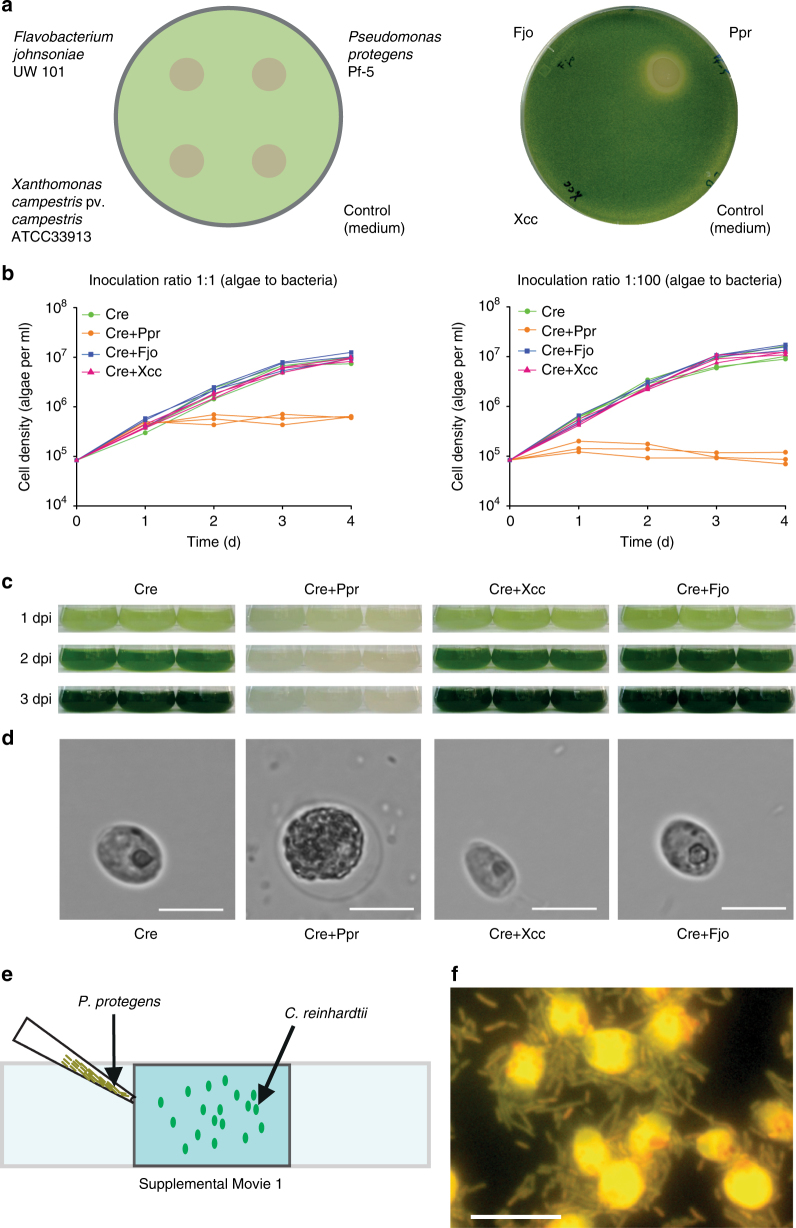

P. protegens Pf-5 arrests the growth of C. reinhardtii

To investigate whether heterotrophic bacteria sharing the same habitat as C. reinhardtii affect algal growth, we selected Flavobacterium johnsoniae, Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris, and P. protegens. Specifically, we used sequenced strains of bacterial species previously isolated from a microalgal culture14 and applied the bacteria to a restricted area on a plate that contains C. reinhardtii cells (Fig. 1a). In coculture with F. johnsoniae or X. campestris, the growth of C. reinhardtii appeared to be unaffected, i.e., comparable to that on the medium control. In contrast, P. protegens strongly inhibited the growth of C. reinhardtii. Likewise, in liquid cultures (inoculation ratio of 1:1 and 1:100 algae to bacteria), only P. protegens substantially decreased the cell density of C. reinhardtii compared to pure algal cultures (Fig. 1b). Algal growth was stopped within the first day in coculture (1:100 ratio) or starting 1 day after inoculation (1:1 ratio). Photographs taken of the cultures in a replete medium show that the typical green color of the algal culture is absent when cocultivated with P. protegens (1:100 ratio) (Fig. 1c), indicating the arrest of the algal growth. Furthermore, in contrast to the other bacteria, P. protegens altered the morphology of the algal cells within 1 day in coculture. The usually oval algal cells were enlarged and almost circular, and their inner structure became granular (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

P. protegens swarms to C. reinhardtii and leads to growth arrest and changes in algal morphology. a Co-cultivation of C. reinhardtii and bacteria on agar plates after 3 days reveals the inhibitory effect of P. protegens. Suspensions of different bacteria were applied to restricted areas of a plate that contains C. reinhardtii within a top layer of TAP agar. LB medium was used as control. b Liquid co-cultivation at indicated ratios of algae to bacteria used for inoculation shows algal growth arrest in the presence of P. protegens. Cultures were inoculated to obtain initial cell densities of 8.3 × 104 algae per ml, and in coculture 8.3 × 104 (1:1) or 8.3 × 106 (1:100) bacteria per ml were added. Values of triplicate cultures are shown. c Photographs of the experiment depicted in b (1:100 ratio) show algal growth arrest by the color change. d Morphology change of algal cells in the presence of P. protegens after 24 h in mixed culture as compared to an axenic culture by bright-field microscopy using a magnification of ×630. Scale bar: 10 µm. e P. protegens swarms around the algal cells and surrounds them within minutes. Scheme depicting the experimental procedure used to visualize live interaction of P. protegens with C. reinhardtii (Supplementary Movie 1). Overall, 10 µl of an overnight culture of P. protegens in LB medium were introduced from one corner of the coverslip as shown in the scheme. f Cells of C. reinhardtii and P. protegens were immobilized after 10 min in coculture on a coated glass slide and stained with acridine orange. Cells were visualized using fluorescence microscopy at ×1000 magnification. Scale bar: 10 µm. Cre Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Fjo Flavobacterium johnsoniae, Xcc Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris, Ppr Pseudomonas protegens, dpi days post inoculation. a–e All experiments were performed in three biological replicates and representative pictures (d) and a representative Supplementary Movie 1 are shown. f shows a representative section of an acridine orange-stained sample as treated in e, but for 10 min. The experiments were replicated three (a) or two times (e) or performed once (b, d)

It is known that the depletion of micronutrients such as iron or zinc can affect the biocontrol properties of P. protegens 19, 20. To test whether P. protegens may benefit from C. reinhardtii under nutrient-limiting conditions, we omitted the trace elements (Fe, Zn, Cu, Co, Mn, and Mo) from the growth medium. While bacterial growth was largely unaffected in a replete medium (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b), it was enhanced in coculture in a medium lacking micronutrients, as compared to the axenic bacterial culture grown in the same medium (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Algal cells also showed an altered morphology after 1 day in coculture in the medium depleted of micronutrients, and they had lost their flagella (Supplementary Fig. 2b).

To learn more about the dynamics of the interaction of C. reinhardtii with P. protegens, we recorded a video (Supplementary Movie 1). Initially, the algal cells swim freely in the medium. After 19 s, the bacteria were introduced from one corner of the slide (Fig. 1e). Within only 1.5 min, the bacteria start to surround the algal cells that already appear to be immobilized. Two minutes later, the intensity of the swarming reaches a maximum, and algal cells are completely encircled by bacteria. The physical contact of the bacteria and the algae was independently confirmed using an acridine orange-stained fluorescent micrograph after a 10-min incubation time (Fig. 1f).

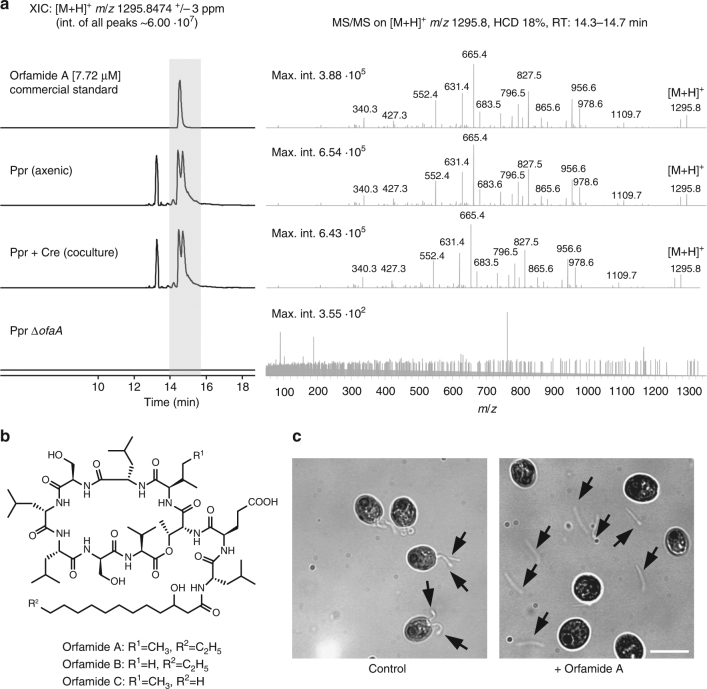

Orfamide A immobilizes several Chlorophyceae

P. protegens biosynthesizes a wide range of natural products, including medium-size molecular weight compounds such as polyketides and nonribosomal peptides21 that could have a role in the bacterial–algal interplay. To study the chemical mediators of the interaction, we monitored two-dimensional patterns of diffusible metabolites between mixed bacterial and algal cultures by MALDI-imaging mass spectrometry (MALDI-IMS)22–24. Organisms were directly grown on disposable indium tin oxide-coated glass slides that were overlaid with a layer of solidified growth medium (Supplementary Fig. 3a). These experiments revealed a cluster of very intense ions, in the range of m/z 1300–1360, localized mainly to the area surrounding the P. protegens growth (Supplementary Figs. 3b and 4). To identify these ions, we analyzed extracts from culture supernatants of P. protegens grown axenically and in coculture with C. reinhardtii by liquid chromatography–high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry (LC–HRMS/MS). The ions detected by MALDI-IMS were also found in the extracts by LC–HRMS, and their exact masses fitted to the natural products orfamides (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 5). We used the commercial standard of orfamide A as a reference and a P. protegens ΔofaA mutant lacking all orfamides25 to confirm the identity of orfamide A (Fig. 2a). Orfamides B and C were also detected in the extracts (Supplementary Fig. 5). Moreover, the extracted-ion chromatogram of m/z 1295.8474 ±3 ppm (orfamide A [M+H]+) showed two additional chromatographic peaks at different retention times compared to orfamide A (even when the mass tolerance window was reduced to 1 ppm), suggesting the presence of undescribed isomers of orfamide A in the extracts (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Orfamide A is released by P. protegens and leads to deflagellation of the algal cells. a Detection of orfamide A by high-resolution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–HRMS/MS). Extracted-ion chromatograms (XIC) of orfamide A (C64H114N10O17, accurate mass 1294.836345 u) [M+H]+ m/z 1295.8474 ±3 ppm and its MS/MS fragmentation pattern are shown for orfamide A commercial standard and different extracts from culture supernatants including an extract of P. protegens in axenic culture, an extract of P. protegens in coculture with C. reinhardtii, and an extract of P. protegens ΔofaA in axenic culture (orfamide deletion mutant). In MS/MS spectra, only the first decimal of m/z values is shown to improve figure legibility. One independent experiment, with one biological replicate and two technical replicates was conducted. b Structures of orfamide A, B, and C. c Orfamide A deflagellates C. reinhardtii. Wild-type cells of C. reinhardtii were grown in TAP medium. A drop of 20 µl culture was applied on the slide. The cells were visualized in a bright-field microscope at ×200 magnification (scale bar: 10 µm); the cell movement was recorded before and after application of 35 µM orfamide A or methanol as control (Supplementary Movies 2–5). To visualize cells that retained or lost their flagella, cells were treated with orfamide A or methanol (control) for 30 s, fixed with 8% potassium iodide and visualized using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy at ×630 magnification. The orfamide and control treatments were done in biological triplicates (see also Supplementary Movies 2–5); a representative picture is shown. The experiment was replicated twice

We next analyzed whether orfamide A (Fig. 2b) alone has an effect on the algal cells. A drop of C. reinhardtii cell suspension was placed on a glass slide, and a video was recorded before adding orfamide A or methanol (negative control), which were carefully applied from the top (Supplementary Movies 2–5). Whereas no effect was observed for the negative control, upon the addition of orfamide A, the cells stopped moving within 30–40 s. Light micrographs from orfamide A treated and untreated cells revealed that exposure to orfamide A results in the rapid deflagellation of algal cells (Fig. 2c). These results suggest that the bacteria employ orfamide A as a tool to incapacitate the algal cells, and thus the algal cells lose the ability to evade the bacteria by swimming away.

The specificity of orfamide A-triggered loss of motility was further tested with flagellated algae other than C. reinhardtii. Therefore, a drop of algal cell suspension was placed in each case on a glass slide, and the cells were visualized using bright-field microscopy. A video was recorded before and after adding orfamide A. Negative controls with methanol that were carried out as well did not influence motility in any case (not shown). Other Chlorophyceae, such as the closely related marine Chlamydomonas sp. SAG 25.89 (Supplementary Fig. 6), Haematococcus pluvialis of the order of Chlamydomonadales, as well as the colony-forming Gonium pectorale of the order of Volvocales lost motility to a large extent upon orfamide A treatment (Table 1; Supplementary Movies 6–11). In contrast, Pedinomonas minor, a Chlorophyte more distantly related to C. reinhardtii from the class of Pedinophyceae as well as the Euglenophyte, Euglena gracilis, retained motility upon orfamide A exposure (Table 1; Supplementary Movies 12–15). These data indicate that orfamide A specifically affects the motility of algae from the Chlorophyceae, whereas tested algae outside this taxonomic class are not vulnerable to this bacterial secondary metabolite.

Table 1.

Loss of motility of exemplary flagellate algae upon treatment with orfamide A

| Species | Class | Phylum | Habitat | Loss of motility | Supplementary videos |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | Chlorophyceae | Chlorophyta | FW/WS | Yes | 2–5 |

| Chlamydomonas sp. | Chlorophyceae | Chlorophyta | Marine | Yes | 6, 7 |

| Haematococcus pluvialis | Chlorophyceae | Chlorophyta | FW/WS | Yes | 8, 9 |

| Gonium pectorale | Chlorophyceae | Chlorophyta | FW/WS | Yes | 10, 11 |

| Pedinomonas minor a | Pedinophyceae | Chlorophyta | FW/WS | No | 12, 13 |

| Euglena gracilis | Euglenophyceae | Euglenophyta | FW/WS | No | 14, 15 |

FW Freshwater, WS wet soil

Orfamide A was applied at a concentration of 35 µM

aNon-axenic strain

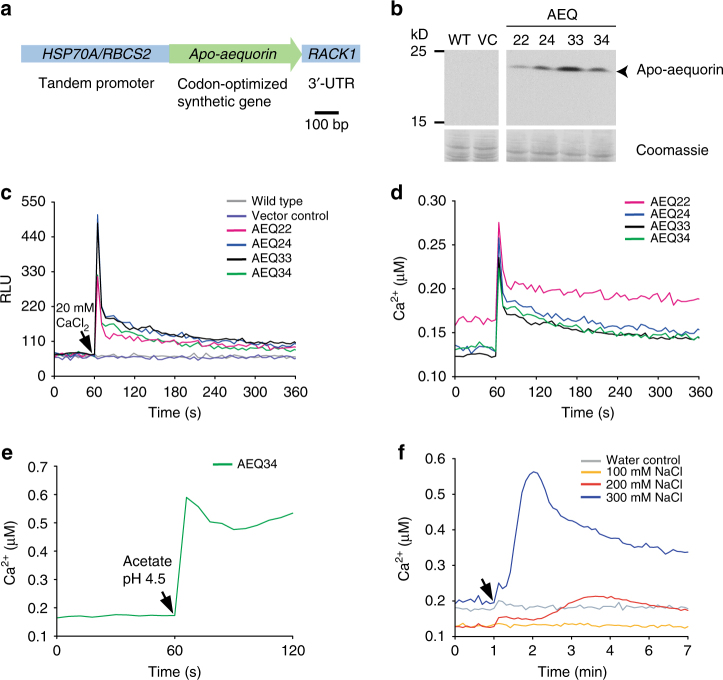

Establishment of an aequorin reporter in C. reinhardtii

Since it is known that Ca2+ spikes can cause flagellar excision in C. reinhardtii 26, we aimed at monitoring cytosolic Ca2+ changes in situ during the microbial interaction. For this purpose, we established an aequorin reporter system in C. reinhardtii. We constructed a gene cassette containing the apo-aequorin gene of Aequoria victoria 27, which was codon optimized for efficient expression in C. reinhardtii, and introduced it into the algal cells (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 7). Several transgenic lines (AEQ22, AEQ24, AEQ33, and AEQ34) expressed the 22-kD apo-aequorin successfully (Fig. 3b) and were selected for further examination.

Fig. 3.

Establishment of an aequorin-based calcium assay in C. reinhardtii and its applicability for abiotic stresses. a The apo-aequorin expression cassette includes a codon optimized gene and cis-acting elements for efficient expression (Supplementary Fig. 7). b Immunoblot showing the expression of apo-aequorin (22 kD) in transgenic lines AEQ22, AEQ24, AEQ33, and AEQ34 compared to wild type (WT) and a vector control (VC). As a loading control, selected protein bands from the Coomassie-stained PVDF membrane are shown. Another biological replicate showed qualitatively identical results. c, d External calcium triggers luminescence in aequorin-expressing lines. After measuring the resting Ca2+ concentration in relative light units (RLU), 20 mM of external CaCl2 were added as indicated by the black arrowhead. Obtained RLU values (c) were converted to relative Ca2+ concentrations (d) by triggering maximal luminescence (Supplementary Fig. 8). e Acidification of the medium causes a prompt increase in cytosolic Ca2+ ions. After measurement of the resting Ca2+ concentration, sodium acetate buffer pH 4.5 was added to a final concentration of 20 mM (black arrowhead) to AEQ34 cells in HEPES buffer pH 7.4. f Salt stress results in an increase in Ca2+ ions. Coelenterazine loaded cells of transgenic aequorin reporter line AEQ34 were treated with increasing concentrations of NaCl (black arrowhead) as indicated. As a control, an equivalent volume of deionized water was used. c–f Each line in the graphs represents the mean of three biological replicates and each biological replicate includes three technical replicates. All experiments were replicated twice except for e, which was done once

As high extracellular Ca2+ concentrations reportedly cause an increase of cytosolic Ca2+ levels28, we initially analyzed aequorin activities by providing external Ca2+ to the AEQ cell lines. Notably, upon addition of excess of external Ca2+, all four transgenic AEQ lines immediately showed a luminescence spike (Fig. 3c). This response was neither observed in the wild type nor in the negative control containing the vector only. In order to estimate the intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, cell lysis was performed at the end of the measurement using an ethanol-containing saturating solution of Ca2+ to trigger the maximum luminescence (Supplementary Fig. 8; Fig. 3d). We also compared maximum luminescence values dependendent on the age of the cells, which was the highest during the exponential growth phase (Supplementary Fig. 9). To further validate our reporter system, abiotic stimuli (abrupt acidification29 and salt stress30) previously demonstrated to increase intracellular Ca2+ levels were applied to the transgenic strains. In both cases, the luminescence increased as expected (Fig. 3e, f).

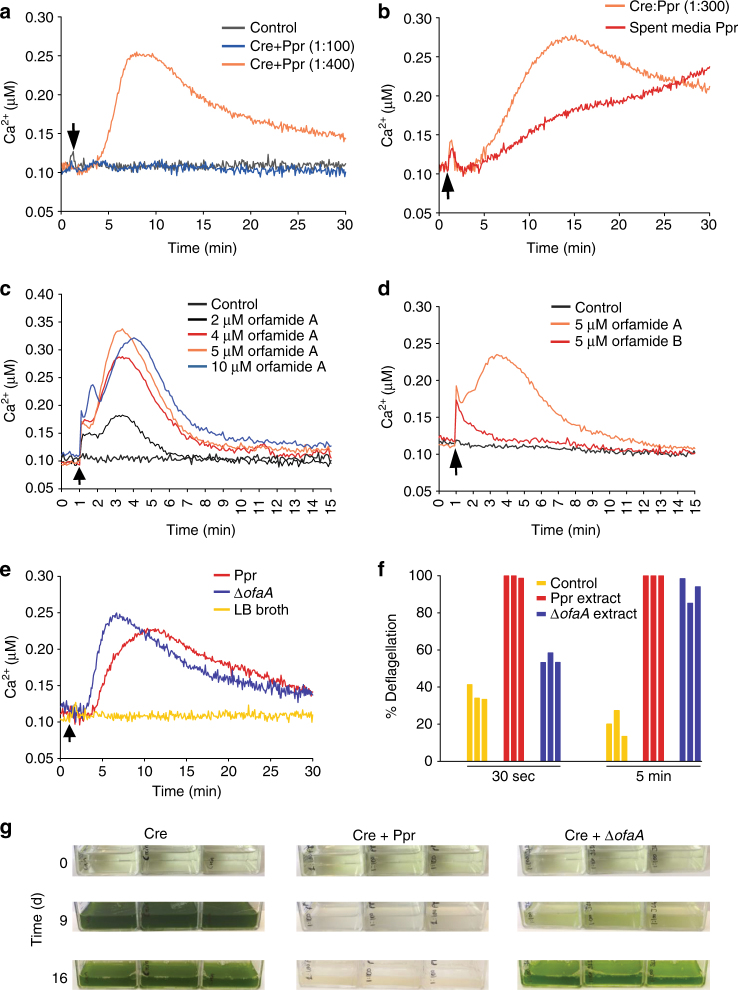

Orfamides trigger a Ca2+ signal and influence algal growth

With a reliable aequorin reporter system at hand, we next studied the biotic interactions of C. reinhardtii. The Ca2+ response in aequorin-expressing C. reinhardtii cells was measured in the presence of P. protegens cells at different ratios (algae:bacteria 1:100 and 1:400). At a 1:100 ratio, no changes in cytosolic Ca2+ levels could be observed within the first 30 min of incubation (Fig. 4a), whereas a strong Ca2+ signal occurred at a ratio of 1:400 after just 5 min. These results show that the interaction between C. reinhardtii and P. protegens cells results in a very fast alteration of the intracellular Ca2+ level, once a critical number of bacterial cells surrounding the algae (Supplementary Movie 1) is reached. In contrast, when adding X. campestris or F. johnsoniae cells at the same ratios, no Ca2+ release was triggered (Supplementary Fig. 10a and b). Even a 4500-fold excess of X. campestris or F. johnsoniae did not trigger a Ca2+ signal, demonstrating that the response of C. reinhardtii is not generally caused by the presence of bacteria, but it is specific to P. protegens.

Fig. 4.

Orfamides cause a rapid increase in cytosolic Ca2+ and contribute to deflagellation and algal growth arrest. a P. protegens is able to trigger Ca2+ changes in C. reinhardtii. Time course of cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations after addition of bacteria to AEQ34 cells. For the Ca2+ measurements, the bacterial cell density was adjusted to the indicated cell ratios. As control, LB broth was added (black arrowhead). b Effect of P. protegens spent medium on cytosolic Ca2+ levels in C. reinhardtii. Aequorin-expressing cells (AEQ34) were incubated with P. protegens in a ratio of 1:300 and used for the measurement. Further, sterile-filtered spent medium from an overnight culture of P. protegens (black arrowhead) was used. c Orfamide A elicits dose-dependent Ca2+ changes. Orfamide A that was dissolved in methanol and further diluted in TAP medium was added to cells at the indicated concentrations. As control, methanol proportional to that of the highest concentration of orfamide A was used. d Ca2+ measurement upon treatment with 5 μM orfamide A or B. As control, methanol was used. e Ca2+ measurements with wild-type P. protegens or ΔofaA mutant at a ratio of 1:400 of algae to bacteria. f Extracts prepared from supernatants of P. protegens and the ΔofaA mutant cultures, respectively, having similar cell densities (around 3.14 × 108 and 3.16 × 108 cells ml−1, respectively) were incubated with C. reinhardtii at a 1% concentration for 30 s or 5 min in triplicates. A 1% extract of TAP medium was taken as control. g Liquid co-cultivation of C. reinhardtii together with wild-type P. protegens or ΔofaA mutant compared to axenic algal cultures. A 1:100 ratio of algae to bacteria was used for inoculation with an initial concentration of 105 algal cells per ml. The corresponding growth curves are depicted in Supplementary Fig. 12. a–e Each line in the graph represents the mean of three biological replicates, and each biological replicate includes three technical replicates. All experiments were replicated twice except for f that was performed once with one biological and three technical replicates. The experiment in g was performed twice with three biological replicates

We also found that a direct contact of P. protegens with the algal cells is not required to trigger the Ca2+ release. The cell-free supernatant of the bacterial culture also caused a signal in the aequorin reporter line (Fig. 4b), thus showing that a diffusible signal is responsible for the Ca2+ release. Next, we tested the capability of orfamide A to cause alterations in cytosolic Ca2+ in a manner similar to the coculture and the supernatant of P. protegens. Solutions of pure orfamide A at different concentrations were added to the algal aequorin reporter line. Whereas the control with the solvent alone showed no alteration, we observed a dose-dependent change in the Ca2+ levels up to ~5 µM orfamide A within the first 5 min after the addition of orfamide A. Higher levels of orfamide A (10 µM) resulted in saturation (Fig. 4c). These data unequivocally show that orfamide A affects Ca2+ homeostasis in the bacterial–microalgal interaction. In addition, the concentration-dependent response up to ca. 5 µM orfamide A mirrors the effect of the bacterial cell density when surrounding the algae, thus causing a high orfamide A concentration in the vicinity of the microalgae.

The extended response of C. reinhardtii to the spent media of P. protegens (Fig. 4b) suggested that chemical mediators other than orfamide A may also contribute to the signal. As orfamide B was also identified in P. protegens (Supplementary Fig. 5) and is commercially available, we analyzed if it has a similar effect as orfamide A. We observed that orfamide B triggers a Ca2+ release, whose signature, however, differs from that of orfamide A (Fig. 4d). A sharp peak of low amplitude observed immediately after the addition of orfamide A was also present with orfamide B, but the larger and broader response found with orfamide A was missing. Yet, orfamide B deflagellates the algal cells (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Orfamides are biosynthesized from an operon consisting of three structural genes known as ofaA, ofaB, and ofaC, encoding nonribosomal peptide synthetases31, 32. To investigate the in vivo role of orfamides in algal–bacterial mixed cultures, we used a ΔofaA mutant25 that lacks all orfamides. The observation that this mutant is still able to elicit a Ca2+ signal (Fig. 4e) indicates that P. protegens produces infochemicals other than the orfamides with the capacity to influence the cytosolic Ca2+ levels in C. reinhardtii. However, a 1% extract from the culture supernatant of the ΔofaA mutant deflagellated algal cells after 30 s only at a relatively low rate compared to the supernatant from a P. protegens culture (Fig. 4f). After a longer incubation time (5 min), the rate of deflagellation was high in both cases (Fig. 4f). These data show that the orfamides contribute to the rapid deflagellation event of algal cells. We also looked at the growth of algal cells in coculture with the mutant. Although the ΔofaA mutant initially suppressed algal growth in a coculture assay, the algae recovered and started to grow after 9–10 days (Fig. 4g; Supplementary Fig. 12). In contrast, wild-type P. protegens suppressed algal growth over a period of 19 days. Although these data provide strong evidence that further secondary metabolites contribute to the complex interplay between P. protegens and the algae, they clearly suggest at the same time that the orfamides are involved in the antagonistic effect exerted by P. protegens on the algae.

Orfamide induces channel-based influx of extracellular Ca2+

In the next step, we focused further on the effect of orfamide A and examined if it is able to alter the morphology of C. reinhardtii, as observed after 24-h incubation of the algae with P. protegens (Fig. 1d). Exposure of algal cells to 35 µM orfamide A resulted in deflagellation, as described before, but the oval shape of the cells was largely unaffected (Fig. 5a, left image). In a few cases, a circular and enlarged morphology was also visible after 24 h (Fig. 5a, medium and right images) that was not observed in the control. These data show that orfamide A has the capability to alter the morphology and suggest that a coordinated action of orfamides as well as of other chemical compounds is needed for large-scale changes in morphology after 24 h.

Fig. 5.

Orfamide A induces influx of extracellular Ca2+, probably through an unidentified channel. a Cell morphology of C. reinhardtii exposed to 35 µM of orfamide A after 24 h. The density of algal cells was 4 × 106 cells ml−1. Algal cells were observed by bright-field microscopy using a magnification of ×400 (scale bar: 10 µm). b Evans blue staining of wild-type C. reinhardtii (strain SAG 73.72) upon treatment with orfamide A and mastoparan at the indicated concentrations. As controls, methanol or water were used at equivalent concentrations. c Deflagellation of wild-type C. reinhardtii upon treatment with orfamide A and mastoparan at the indicated concentrations. As control, methanol or water were used at equivalent concentrations. d Orfamide A triggers Ca2+ changes mostly from external pools. AEQ34 cells were grown in TAP medium for 72 h. Before incubation with coelenterazine, the TAP medium was replaced with TAP lacking Ca2+ and the cells were incubated with 50 µM EGTA for 5 minutes before commencing the Ca2+ measurement. As negative control, AEQ34 cells in TAP lacking Ca2+ were treated with methanol. e Deflagellation of wild-type C. reinhardtii upon treatment with 35 µM of orfamide A in TAP medium or TAP lacking Ca2+ (see d). In the latter case, the cells were washed three times with TAP lacking Ca2+ supplemented with 50 µM EGTA before the treatment with orfamide A. f Deflagellation in the adf-1 mutant and its underlying wild type (WT, strain CC-620) upon treatment of cells with 35 µM of orfamide A. g Lanthanum (La3+) inhibits orfamide-induced Ca2+ signaling. Overall, 20 µM LaCl3 were added to the cells in HEPES buffer, pH 7.4, 1 min before the Ca2+ measurement was started. In b, c, e, and f, all experiments were performed with three biological replicates and were replicated twice (b, c, f) or once (e). Error bars represent the standard deviation. In d and g, each line in the graph represents the mean of three biological replicates, and each biological replicate includes three technical replicates. Except for a, which was performed once, all experiments were replicated twice. In a, representative pictures are shown

We further checked if the deflagellation and the increase in Ca2+ in the algal cells are caused by permeabilization effects by orfamide A using the vital stain Evans blue. In the positive control, 10 µM mastoparan, known as a permeabilization agent33, leads to an efficient staining of approximately 80% of the Chlamydomonas cells with Evans blue (Fig. 5b) and concomitant high rates of deflagellation (Fig. 5c). In contrast, 35 µM (used in Fig. 2c) as well as 10 µM orfamide A, which still causes ~80% of deflagellation (Fig. 5c) did not result in an increased staining of Chlamydomonas cells compared to the control (Fig. 5b). Algal cells treated with 10 µM orfamide B did not show increased permeability to Evans blue either (Supplementary Fig. 11). These data show that orfamides do not provoke a major permeabilization of the algal cells—at least not on a short term—for orfamide-induced deflagellation in Chlorophyceae as observed with orfamide A (Table 1, see Discussion).

To investigate whether the orfamide-mediated rise in cytosolic Ca2+ is due to an influx of Ca2+ from the extracellular medium or if it is released from intracellular Ca2+ stores, we resuspended the cells in a medium lacking Ca2+ ions that had been additionally supplemented with 50 µM EGTA to sequester any possibly existing residual Ca2+ ions. Upon exposure of the cells to orfamide A, we observed only a very small increase in Ca2+ in this case, indicating that the orfamide-triggered rise in Ca2+ requires an influx of Ca2+ from outside the cell (Fig. 5d). We also investigated the link between the presence of Ca2+ in the medium, the action of orfamide A, and deflagellation. For this purpose, we examined the rate of orfamide-induced deflagellation in C. reinhardtii in a medium with or without Ca2+. Clearly, orfamide A-based deflagellation depends on the presence of Ca2+ in the medium (Fig. 5e). These findings link the Ca2+ uptake caused by the presence of orfamide A and consequently triggered deflagellation, pointing to the cytosolic Ca2+ elevation as the trigger for deflagellation.

In the next step, we used a mutant known as adf-1, which encodes for a Ca2+ channel shown to be responsible for deflagellation via influx of Ca2+ upon acid shock. The involved Ca2+ channel was recently identified as TRP1529, 34. The adf-1 mutant was efficiently deflagellated upon orfamide A treatment (Fig. 5f), suggesting that the TRP15 channel is not involved (or is at least not the only Ca2+ channel) in the orfamide A signaling pathway. If the Ca2+ channel blocked in the adf-1 mutant was the sole channel mediating the Ca2+ influx, orfamide A would not cause a significant increase in Ca2+ in this mutant and the mutant would not deflagellate. In contrast, if another Ca2+ channel of Chlamydomonas is involved, deflagellation would occur.

To test this possibility, we used lanthanum (La3+), a well-known inhibitor of Ca2+ channels29, 35. The addition of orfamide A in the presence of La3+ resulted in a massively reduced level of Ca2+ compared to the absence of La3+ (Fig. 5g). Altogether, our results indicate that orfamide A from P. protegens induces the influx of extracellular Ca2+ through an unidentified Ca2+ channel (other than TRP15) in the algal plasma membrane.

Discussion

Ca2+ signaling has been implicated in early stages of higher plant–microbe interactions of both symbiotic and antagonistic nature36. Likewise, in marine diatoms, environmental signals and intraspecies interactions can activate Ca2+ signaling37, 38. By means of an aequorin reporter line, we have demonstrated that bacteria substantially perturb the cytosolic Ca2+ levels in C. reinhardtii at different time scales, within minutes (Fig. 4a) to hours (Supplementary Fig. 13). The changes in Ca2+ do not necessarily result in deflagellation of a C. reinhardtii cell, but are also involved in light-signaling pathways from the eyespot to the flagella, thus controlling algal movements39. Similarly, elevated salt concentrations evoke an increase in Ca2+, but not deflagellation30. The strong rise in Ca2+ in response to acidification and salt stress26, 29, 30 was confirmed with the aequorin assay in this study (Fig. 3e, f), and a rapid increase in Ca2+ is also evident upon orfamide A and B treatment (Fig. 4d).

Experiments with calcium-sensitive dyes have shown that localization of Ca2+ primarily in the apical part of the algal cell and the timing of the Ca2+ signals are important factors in acid-induced deflagellation26. In agreement with this regulatory role of Ca2+ signals in deflagellation, we observed that both orfamide-induced Ca2+ elevation (Fig. 5d) and deflagellation (Fig. 5e) depend on the presence of extracellular Ca2+ ions. Although stresses often elicit Ca2+ responses in C. reinhardtii that can lead to deflagellation29, 30, our results point to a more specific role of orfamides. We show that orfamide A exposure results in cytosolic Ca2+ increase, which requires a Ca2+ influx from outside the cell without causing a major permeabilization of the plasma membrane (Figs. 4c and 5b, d). The fact that this Ca2+ signal is inhibited by La3+ (Fig. 5g), a Ca2+ channel blocker29, 35, suggests that orfamide A targets a Ca2+ channel in the algal plasma membrane. In the light of these findings, an alternative mode of action of orfamides as Ca2+ carriers or small Ca2+-selective pores that are not permeable to Evans blue seems to be less likely, but remains to be tested.

In this context, it is also of interest that Chlamydomonas has an unusually high number (>30 predicted by its genome) of Ca2+ channels, especially of the TRP type40, most of which have not been characterized so far. It seems likely that one of them is part of the orfamide-signaling pathway. Since the well-characterized Chlamydomonas TRP15 Ca2+ channel34 is not involved in orfamide A-triggered Ca2+ uptake (or is not the only Ca2+ channel involved in this process) (Fig. 5f), the target of orfamide remains to be identified. Orfamide A may bind directly to its Ca2+ channel target, or induce channel opening indirectly, for example, by binding to another protein or lipid component of the plasma membrane. The distinct response of orfamide B (Fig. 4d) that differs from orfamide A by only one methyl group (Fig. 2b) might indicate that orfamide B may even trigger a different pathway than orfamide A. The specificity of orfamide A in immobilizing Chlorophyceae algae, but not two species from the Pedinophyceae and Euglenophytes, respectively (Table 1), further supports a specific mechanism and a signaling role of these cyclic lipopeptides that involves specialized membrane components unique to Chlorophyceae.

The majority of characterized lipopeptides interacts with lipid components of membranes, such a daptomycin, which was recently found to interfere with fluid membrane microdomains41. In some cases, however, protein targets were also identified42. In addition to the deflagellating and Ca2+-eliciting activities associated with orfamide A, which manifest themselves within minutes (Figs. 2c and 4c), this secondary metabolite also starts to disturb the morphology of C. reinhardtii over a time scale of 24 h (Fig. 5a). While staining with Evans blue indicates that orfamide A does not disrupt the algal cell membrane on the short term (Fig. 5b), membrane disruption may occur on the long term. Whether the different effects of orfamide A on C. reinhardtii are based on a single or multiple molecular interactions with components of the algal plasma membrane needs to be addressed in future work. In zoospores of the oomycete Phytophthora ramorum, a nonphotosynthetic member of the Heterokontophyta, orfamide A causes both immobilization and cell lysis within minutes31. The structure of the cell wall, which is absent from P. ramorum zoospores, and also the composition of the plasma membrane may explain why orfamide A exerts different effects on P. ramorum 31 and different photosynthetic algae (Table 1; Figs. 1d and 2c).

Mutation of ofaA in P. protegens results in the stop of orfamide production and defects in swarming (movement on soft agar) of the bacteria31. Bacterial lipopeptides, specifically orfamides, have been known to play different roles, e.g., as biosurfactants, as antifungal biocontrol agents, or as insecticides31, 43. We have now revealed an interkingdom function of orfamides A and B as precise saboteurs of eukaryotic signaling pathways, resulting in the immobilization of flagellated algal cells by interference with intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis. These cyclic lipopeptides thus represent novel biotic factors that cause Ca2+-dependent deflagellation in microalgae. Experiments with the ΔofaA mutant (Fig. 4e, f, g) showed that orfamides are not essential for P. protegens to induce Ca2+ signaling and deflagellation in C. reinhardtii. The algal Ca2+ signal elicited by the ΔofaA mutant was slightly faster than the signal elicited by the wild type (Fig. 4e), whereas deflagellation was delayed when an extract from the ΔofaA mutant was used (Fig. 4f). Although the reason for these different effects is currently unclear, not every Ca2+ signal triggers deflagellation (as mentioned above), and different Ca2+ signatures may induce different downstream responses with different efficiencies. Our findings with the ΔofaA mutant further show that P. protegens also produces other chemical mediators in addition to orfamides that possess Ca2+-eliciting and deflagellating activities, albeit rapid deflagellation (within 30 s) seems to be mainly associated with exposure to orfamides (Fig. 4f). Although these mediators may employ the same or alternative signaling pathways compared to orfamide A, the observed redundancy may indicate that Ca2+ elicitors and deflagellating compounds could aid to improve the fitness of P. protegens. In any case, the recovery of algal growth in the presence of the ΔofaA mutant after ~10 days (Fig. 4g) indicates that a few algae survive the encounter when orfamides are absent, highlighting that orfamides help P. protegens to compete with C. reinhardtii.

The strategy used by P. protegens (Fig. 6) differs markedly from previously reported tactics of bacteria that secrete algicidal agents and results in high concentrations of orfamides around the algal cells simply by the accumulation of the bacteria around the algae, as visualized in Supplementary Movie 1. This behavior results in the stop of the algal growth and altered cell morphology (Fig. 1b, d). We hypothesize that immobilization of the algal cells helps the bacteria to acquire nutrients from the algae. Bacterial growth is enhanced in coculture when the surrounding medium lacks trace elements (Supplementary Fig. 2), which are most likely delivered by the algal cells. However, the evidence for a benefit for the bacteria is currently limited, and further experiments are necessary to identify the specific nutrients obtained from the compromised algal cells. In addition to one or more trace elements, phosphate or sources of carbon or nitrogen that are present in the used medium may also have a role in the algal–bacterial interplay.

Fig. 6.

Proposed model of paralysis of algal cells by P. protegens. During the antagonistic interaction of P. protegens with C. reinhardtii, the cyclic lipopeptide orfamide A as well as yet unknown other chemical mediator(s) (indicated by blue squares) produced by the bacteria accumulate around the algal cells. Orfamides and the other compound(s) elicit a cytosolic Ca2+ signal in the green algae by triggering the influx of external Ca2+, at least in the case of orfamide A. Algal cells then become paralyzed by deflagellation, which seems to help P. protegens to acquire micronutrients

Beyond the new molecular insights, our findings also seem to be relevant from an ecological perspective because they contribute to a better mechanistic understanding of algal blooms that are part of phytoplankton. Algal blooms can affect the environment in two ways; they are not only major contributors to global photosynthesis, but can also be highly toxic, poisoning fish and shellfish44. Unicellular flagellated algae and colony-forming algae such as Gonium or Pleodorina, which are related to C. reinhardtii, can also form blooms45. Our data show that closely related wet soil and freshwater, as well as marine Chlorophyceae are likely subject to a similar deflagellation mechanism as C. reinhardtii because they get immobilized by orfamide A (Table 1). P. protegens is found in all these environments17, 46, and P. protegens and a closely related P. fluorescens strain have been reported to control algal blooms in freshwater and marine ecosystems, respectively3, 44. Therefore, the microbial interaction that we unraveled seems to be transferable to other flagellate Chlorophyceae algae, thus providing new tools to interfere with algal blooms of such species.

Methods

Strains and culture conditions

C. reinhardtii strain SAG 73.72 (mt+) was used as a wild type for most of the performed experiments. In some cases, mutant adf-1 (CC-2919) with a defect TRP15 Ca2+ channel was used together with its parental strain CC-620. SAG 73.72 was obtained from the algal culture collection in Göttingen and CC-620, as well as the mutant CC-2919 from the Chlamydomonas Center at the University of Minnesota, USA. C. reinhardtii cells were grown in Tris-acetate-phosphate (TAP) medium47 in a light dark regime of 12:12 (unless otherwise indicated) with a light intensity of 50 µmol photons m−2 s−1 and stirring (250 rpm). The bacterial strains F. johnsoniae UW10148, X. campestris pv. campestris ATCC33913 49, and P. fluorescens Pf-550 renamed to P. protegens Pf-517 were usually grown in LB medium at 28 °C with orbital shaking (200 rpm). The ΔofaA deletion mutant25 was kindly provided by H. Gross (University of Tübingen), which he had obtained in turn from J.E. Loper (Oregon State University, USA) and B.T. Shaffer (OSU and UCSD-ARS). For the agar-based coculture assay, algal cells were grown under continuous light conditions (50 µmol photons m−2 s−1). Bacterial cells were grown in TAP medium for this coculture assay. Transgenic cell lines expressing the apo-aequorin reporter (AEQ, see below) were maintained on TAP agar plates (2% agar) with hygromycin B (20 µg ml−1). For Ca2+ measurement experiments, algal cells were grown in TAP medium without any antibiotics and the bacteria were grown in LB medium.

Other flagellate algae were obtained from the culture collection of algae and protozoa of the Scottish Marine Institute in United Kingdom (Haematococcus pluvialis, strain CCAP 34/8 and Gonium pectorale, strain CCAP 32/4), from the culture collection in Göttingen, Germany (Chlamydomonas sp., strain SAG 25.89 that was identified as CCMP 235, see Supplementary Fig. 6 and Euglena gracilis, strain SAG 1224-5/25) or were kindly provided by C. Wilhelm (Pedinomonas minor, SAG 1965-3), University of Leipzig, Germany. These flagellate algae were grown in media whose recipes are provided by the mentioned algal collections. Briefly, H. pluvialis, G. pectorale, and P. minor were grown in 3N-BBM + V medium, E. gracilis in 3N-BBM+V supplemented with 1 g l−1 sodium acetate trihydrate, 1 g l−1 meat extract, 2 g l−1 tryptone, and 2 g l−1 yeast extract, and Chlamydomonas sp. SAG 25.89 in a modified version of 3N-BBM+V where 32 g l−1 NaCl had been added and the NaNO3 had been replaced with 7 mM NH4Cl.

Co-cultivation of C. reinhardtii and bacteria

For mixed cultivation of algae and bacteria on agar plates, a TAP plate (2% agar, 92 mm diameter) was overlaid with 3.3 ml 0.5% TAP agar (cover agar) containing 2 × 106 C. reinhardtii cells. Overall, 15 µl of an overnight bacterial culture (containing between 2.1 and 2.5 × 106 cells) were then applied to the surface of the solidified plate. The plates were incubated under continuous light (50 µmol photons m−2 s−1) at 20 °C and documented by scanning. For the mixed cultivation of algae and bacteria in liquid culture, C. reinhardtii and bacteria were grown in 100 ml conical flasks containing 50 ml TAP medium under continuous light (50 µmol photons m−2 s−1) and stirring (200 rpm) at 20 °C. Algal cell densities were determined by counting using an improved Neubauer chamber (no. T729.1, Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). Bacterial cell densities were determined as colony-forming units (CFU) by plating diluted bacterial culture on LB agar plates and counting CFUs.

For recording the cell densities of algae (C. reinhardtii) alone and in coculture with bacteria (P. protegens or the ΔofaA mutant) (Supplementary Fig. 12), cells were grown in 50 ml NUNC cell culturing flasks containing 20 ml of TAP medium on a rotary shaker (200 rpm) at 23 °C. For each time-point, 1 ml of culture was transferred into a 2 ml Eppendorf tube, cooled down to 4 °C and centrifuged for 2.5 min at 200×g. The supernatant containing the bacteria was transferred to a new Eppendorf tube and the pellet bearing the algal cells was resuspended in 1 ml of TAP medium. OD was then measured at 700 nm and the cell density was estimated using a calibration curve done with the axenic cultures of C. reinhardtii.

For mixed cultivation of C. reinhardtii and P. protegens in liquid TAP medium free of trace elements (TAP-TE), bacteria were washed three times in TAP-TE medium and used to inoculate 50 ml TAP-TE in 100 ml conical flasks to an initial density of 106 cells ml−1. Bacteria were grown under continuous light (50 µmol photons m−2 s−1) and stirring (200 rpm) at 20 °C. After 24 h, algae were added at a ratio of ~1:100 algae to bacteria, and the growth of the bacteria was determined by plating different dilutions on LB agar plates and counting CFUs.

To record Supplementary Movie 1, wild-type cells of C. reinhardtii were grown to a cell density of 3–4 × 106 cells ml−1. 20 µl of algal cells in TAP medium were dripped on a glass slide and a coverslip was placed gently over the spot. A total of 10 µl of a bacterial culture grown overnight (in LB medium) were introduced from the corner of the coverslip. The cells were observed under the microscope at ×400 magnification using the software Zen (blue edition, Carl Zeiss).

To record Supplementary Movies 2–15 (documentation of the effect of orfamide A on the motility of C. reinhardtii and other flagellate algae), 18 µl of algal culture (3 × 106 ml−1) were placed as drop on an 8 well diagnostic glass slide (Thermo scientific) except for E. gracilis, where a concentration of 6 × 105 ml−1 cells was used due to its large cell size. Overall, 2 µl of orfamide A in the corresponding medium were carefully added to the droplet to reach a final concentration of 35 µM orfamide A. The cells were visualized and recorded in movie using the software Zen (Blue edition, Carl Zeiss) before and after 30–60 s adding orfamide A. In case of P. minor and E. gracilis, movies were taken after 5 min to verify that orfamide A still has no effect after a longer period. All experiments for the Supplementary Movies were replicated twice.

Acridine orange staining and fluorescence microscopy

C. reinhardti (4 × 106 cells ml−1) and P. protegens (1.7 × 109 CFU ml−1) cells were mixed in a ratio of algae to bacteria of ~1:400. 50 µl of the mixed cell suspension were applied on glass slides coated with poly-l-lysine. The suspension was allowed to stand for 10 min at room temperature. After incubation, the slide was dipped in ice cold methanol for 20 s followed by drying. Using a modified protocol51, the slide was stained with 100 µg ml−1 acridine orange in 1% (v/v) acetic acid for 2 min followed by gentle washing with deionized water. The cells were visualized using a fluorescence microscope (Axiophot, Carl Zeiss) equipped with suitable filters (excitation at 450–490 nm and emission at 520 nm). The images were recorded using Axiocam ICc1 camera along with the software Zen (blue edition) at a magnification of 1000 x.

MALDI-imaging mass spectrometry

The main challenge for microbial MALDI-imaging mass spectrometry is to ensure complete contact between the sample and the conductive surface where the measurements take place52. While microbes can be cultured on non-disposable MALDI target slides52, we used indium tin oxide (ITO) coated glass slides that allowed storage of samples for several months and re-analysis if needed. Furthermore, our sample preparation method avoids transfer of delicate samples before MALDI-imaging mass spectrometry measurements, and it prevented flaking of the agar layer during the drying step, measurement, and storage.

For mixed cultivation of algae and bacteria, sterilized ITO coated glass slides (Bruker Daltonics) were placed inside petri dishes and overlaid with 3.3 ml 0.5% TAP agar containing C. reinhardtii at a density of ~9 × 105 cells ml−1. 10 µl of P. protegens (~1 × 109 cells ml−1) washed in TAP medium were then applied to the surface of the solidified agar medium. For comparison, axenic samples were prepared in the same way, but by omitting either algal or bacterial cells. The petri dishes were closed and wrapped with parafilm. The cultures were incubated at 20 °C and continuous light (50 µmol photons m−2 s−1). After 3 days, the parafilm and any condensed water were removed, and the petri dishes were wrapped with Micropore tape (3 M). In this way, the slides were stored at room temperature for additional 3 days until the agar was dried.

Matrix preparation followed the protocol proposed in Hoffman and Dorrestein, 201553. Samples were coated with a saturated solution (20 mg ml−1) of universal MALDI matrix (1:1 mixture of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid [DHB] and α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid [HCCA]; Sigma Aldrich) dissolved in ACN/MeOH/H2O (70:25:5, v/v/v). The matrix was sprayed using the automatic system ImagePrep device 2.0 (Bruker Daltonics) in 60 cycles (2 s spraying, 10 s incubation time, and 40 s of active drying using nitrogen gas), rotating the sample 180° after 30 cycles.

The samples were analyzed in an UltrafleXtreme MALDI TOF/TOF (Bruker Daltonics), which was operated in positive reflector mode using flexControl 3.0. The analysis was performed in two ranges: 0–2000 Da range, with 30% laser intensity (laser type 3), accumulating 1000 shots by taking 50 random shots at every raster position; and 700–3500 Da range, with 40% laser intensity (laser type 3), accumulating 1000 shots by taking 50 random shots at every raster position. Raster width was set at 200 µm. Calibration of the acquisition method was performed externally using Peptide Calibration Standard II (Bruker Daltonics) containing bradykinin 1–7, angiotensin II, angiotensin I, substance P, bombesin, ACTH clip 1-17, ACTH clip 18–39, and somatostatin 28.

In addition, spectra obtained in the 0–2000 Da range were processed with baseline subtraction in flexAnalysis 3.3 and corrected internally using the peaks of HCCA (from the matrix; [M+H]+ m/z 190.0499 and [2 M+H]+ m/z 379.0925). Processed spectra were uploaded in flexImaging 3.0 for visualization and SCILS Lab 2015b for analysis and representation. Chemical images were obtained using total ion count (TIC) normalization and weak denoising.

Extraction of extracellular compounds from P. protegens

To prepare spent media extracts for LC-high-resolution MS measurements, starter cultures of P. protegens were grown in 5 ml LB broth in test tubes for 24 h at 28 °C and orbital shaking at 200 rpm. ~7 × 108 cells from 0.5 ml of starter culture were washed three times with TAP medium and used to inoculate 250 ml of TAP medium in a 1 liter conical flask. The culture was grown at room temperature with shaking at 110 rpm. To prepare cocultures, C. reinhardtii cells were added after 24 h in a ratio of 1:100 (algae to bacteria) and incubated for further 24 h. The cells were removed by centrifugation (20 min, 16,000×g, 4 °C). The supernatant was sterile filtrated (CHROMAFIL® CA-20/25 (S), pore size 0.20 µm), extracted three times with ethyl acetate (250 ml), and the extract was dried by rotary evaporation at 40 °C. The dried residue was dissolved in 250 µl of methanol (HPLC grade), and the solution passed through a filter with a pore size of 0.45 µm.

LC-high-resolution MS

The analyses were performed on a Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer coupled to an Accela AS LC system (Thermo Fisher, San José, USA). Organic solvents (LC-MS grade) and reagents used for LC-MS analysis were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. An Accucore C18 column (2.6 µm, 100 × 2.1 mm; Thermo Fisher) was eluted at 0.2 ml min−1 with water (eluent A) and acetonitrile (eluent B) both containing 0.1% formic acid. Gradient elution used was: 5–98% B over 10 min, hold 12 min, 98–5% B in 0.1 min, and hold 6.9 min. Injection volume was 10 µl and the oven temperature was 30 °C. Pure orfamide A and B (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was dissolved in methanol/water (1:1, v/v) to a concentration of 100 ng ml−1. High-resolution full MS experiments (positive ionization) were acquired in the range of m/z 150–2000. The following source settings were used: spray voltage = 3.5; capillary temperature = 250 °C; capillary voltage = 50 V; sheath gas flow = 49 and auxiliary gas flow = 5 (arbitrary units); tube lens voltage = 130 V. Resolving power was set at 35,000 (FWHM at m/z 400). For fragmentation experiments, precursors were selected by the quadrupole with an isolation window of 1 Da, a target value of 2 × 105, and a maximum ion injection time of 200 ms. Precursor ions were subjected to fragmentation with 18 and 22% normalized collision energy in the higher energy collisional dissociation (HCD) cell, and the resulting fragment ions were detected in the Orbitrap mass analyzer at a resolution of 70,000 (FWHM at m/z 400).

Aequorin expression and transformation of C. reinhardtii

The pHD-AEQ2 vector was used for transformation. Its complete sequence is shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. This vector carries a codon optimized apo-aequorin gene27 that was synthesized by GeneArt Life Technologies. The apo-aequorin gene was put under control of the HSP70A/RBCS2 tandem promoter along with the first intron of RBCS2 54 and was set in front of the RACK1 3′-UTR representing a constitutive reference transcript55. The vector also carries the hygromycin B resistance from the Hyg3 vector56 for selection in C. reinhardtii as well as an ampicillin resistance (selection marker for E. coli). C. reinhardtii wild-type cells (strain SAG 73.72) were transformed with the autolysin method as described earlier57. SAG 73.72 cells were transformed with either pHyg3 (vector control) or pHD-AEQ2 (AEQ lines). Hygromycin-resistant colonies were further examined in immunoblots (see below) for expression of apo-aequorin.

Crude extract and immunoblotting

Preparation of crude extracts to detect the apo-aequorin protein was done as described57. For immunoblotting, 50 µg of proteins of a crude extract from cells harvested in the middle of the day were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and the proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidine difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Blocking and detection was done as published before58. The primary antibody used for immunoblotting was anti-aequorin (Covalab, France); it was used at a dilution of 1:2000 in the blocking solution. The secondary antibody was anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase used at a dilution of 1:6666 (Sigma Aldrich). Full blots and stained membranes are presented in Supplementary Fig. 14.

Intracellular Ca2+ measurement using an aequorin reporter

Cells expressing apo-aequorin (SAG 73.72::pHD-AEQ2, abbreviated as AEQ cells) as well as the control cells used for the Ca2+ measurement were grown in TAP medium for 72 h up to a cell density of 3–4 × 106 cells ml−1. The cells were counted using a Thoma cell counting chamber. Prior to the Ca2+ measurement, 1 ml of cells were incubated together with 23 µM of coelenterazine (Synchem, Germany) in the dark for 2 h at room temperature. For the measurement, 96 well plates (white with clear bottom, Berthold technologies #60705) were used. Each well was loaded with 100 µl of coelenterazine-treated cell suspension. The microplate luminometer (LB-941, Mithras Berthold Technologies) was used for the luminescence measurement. The machine was programmed using the software Mikrowin2000 (provided by the manufacturer). The counting time was set between 0.2 and 1 s and the delay between each count was set between 5 and 7 s. For measuring the Ca2+ elevation under the influence of 20 mM CaCl2, 190 µl of cells (AEQ22, AEQ24, AEQ33, or AEQ34) incubated with coelenterazine were loaded in a 96 well microplate; after measurement of background, 10 µl of 400 mM CaCl2 solution was injected followed by RLU measurement for 300 s. Maximal luminescence (full discharge) was determined by adding 100 µl of discharge solution (2 M CaCl2, 10% ethanol) to each well59. Obtained relative luminescence unit (RLU) values were exported to Microsoft Excel and values were converted to molar Ca2+ concentrations using the equation pCa = 0.332588(–log k) + 5.5593 as in ref.59.

Induction of pH and salt stress

Acid-induced deflagellation was done as described26. 100 µl of 40 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5 (40 mM sodium acetate, pH adjusted using acetic acid) were added to 100 µl coelenterazine pretreated AEQ34 cells in HEPES buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 1 mM CaCl2, 50 µM MgCl2, and 1 mM KCl). For salt stress measurements, 100 µl of NaCl (in ddH2O) were added to 100 µl of AEQ34 cells to reach a final concentration of 100, 200, or 300 mM.

Ca2+ measurement under the influence of orfamide A and B

Algal cells were grown in TAP medium for 72 h, the cell density was adjusted to 4 × 106 cells ml−1, and then the cells were pre-incubated with coelenterazine. P. protegens was grown in LB medium overnight. Orfamide A or B (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were dissolved in methanol. For the Ca2+ measurement, this stock solution was diluted in 100 µl of TAP medium before commencing the measurement. To block the Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane, AEQ34 cells grown in TAP medium were suspended in HEPES buffer (see above) after washing the cells three times with the same. Overall, 20 µM lanthanum chloride (LaCl3) was added to the cells before starting the experiment in the 96 well microplate. For preparing TAP medium lacking Ca2+, the salt solution mix for TAP deficient of calcium chloride was used.

Deflagellation and Evans blue staining

Cells were taken at a cell density of 3–4 × 106 cells ml−1. For Evans blue staining, the cells were treated with 10 or 35 µM of orfamide A, 10 µM orfamide B, or 10 µM of mastoparan (Sigma Aldrich, product number M5280) for 30 s followed by brief washing three times for 10 s with TAP medium at room temperature. As control, the samples were treated with an equivalent volume of methanol for orfamides and water in the case of mastoparan. After washing the cells, they were resuspended in 0.1% (w/v) Evans blue stain in TAP medium for 5 min followed by microscopy and cell counting. For deflagellation studies, the cells were treated in similar manner mentioned above, but the washing steps were skipped as the cells were fixed with 4–8% (v/v) potassium iodide after treatment with orfamide and mastoparan. The cells were imaged using DIC microscopy (Axioplan 2 from Zeiss), and counting was performed using Image J (Version 1.48) cell counter.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request. Plasmids and transgenic lines are available from MM on basis of a Material Transfer Agreement.

Electronic supplementary material

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

P.A., D.S., M.G.-A., C.H., S.S., and M.M. are grateful for financial support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for Grant SFB 1127 (ChemBioSys). H.D. and M.M. are thankful for DFG Grant Mi 373-10 and M.G.-A. for an ERC grant for a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship (IF-EF, Project Reference 700036). P.A. has a fellowship from the International Leibniz Research School ILRS (Project Number 321020) in Jena and D.C.F. from the Jena School for Microbial Communication JSMC; P.A. and D.S. are PhD students associated with the JSMC. We thank U. Holtzegel for her suggestion to use the aequorin reporter to study algal–bacterial interactions; A. Mrozinska and R. Oelmüller for advice with the aequorin assay, M. Wich for her help with the vector control transformation, C. Wilhelm for providing Pedinomonas minor as well as H. Gross, J.E. Loper, and B.T. Shaffer for providing the ΔofaA mutant. We are grateful to K. Dunbar and E. Molloy for proofreading the manuscript and valuable comments.

Author contributions

C.H., S.S., and M.M. designed the experiments. P.A., D.S., M.G.-A., D.C.F., and H.D. conducted the experiments. P.A., D.S., M.G.-A., D.C.F., C.H., S.S., and M.M. wrote the article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01547-8.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Severin Sasso, Email: severin.sasso@uni-jena.de.

Maria Mittag, Email: M.Mittag@uni-jena.de.

References

- 1.Field CB, Behrenfeld MJ, Randerson JT, Falkowski P. Primary production of the biosphere: integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science. 1998;281:237–240. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kusari S, Hertweck C, Spiteller M. Chemical ecology of endophytic fungi: origins of secondary metabolites. Chem. Biol. 2012;19:792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung SW, Kim BH, Katano T, Kong DS, Han MS. Pseudomonas fluorescens HYK0210-SK09 offers species-specific biological control of winter algal blooms caused by freshwater diatom Stephanodiscus hantzschii. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008;105:186–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leão PN, et al. Synergistic allelochemicals from a freshwater cyanobacterium. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:11183–11188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914343107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paul C, Pohnert G. Interactions of the algicidal bacterium Kordia algicida with diatoms: regulated protease excretion for specific algal lysis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seyedsayamdost MR, Case RJ, Kolter R, Clardy J. The Jekyll-and-Hyde chemistry of Phaeobacter gallaeciensis. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:331–335. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demuez M, Gonzalez-Fernandez C, Ballesteros M. Algicidal microorganisms and secreted algicides: new tools to induce microalgal cell disruption. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015;33:1615–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hom EF, Aiyar P, Schaeme D, Mittag M, Sasso S. A chemical perspective on microalgal-microbial interactions. Trends Plant Sci. 2015;20:689–693. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merchant SS, et al. The Chlamydomonas genome reveals the evolution of key animal and plant functions. Science. 2007;318:245–250. doi: 10.1126/science.1143609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blaby IK, et al. The Chlamydomonas genome project: a decade on. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19:672–680. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jinkerson RE, Jonikas MC. Molecular techniques to interrogate and edit the Chlamydomonas nuclear genome. Plant J. 2015;82:393–412. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petroutsos D, et al. A blue-light photoreceptor mediates the feedback regulation of photosynthesis. Nature. 2016;537:563–566. doi: 10.1038/nature19358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidts M, et al. TCTEX1D2 mutations underlie Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy with impaired retrograde intraflagellar transport. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7074. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delucca R, McCracken MD. Observations on interactions between naturally-collected bacteria and several species of algae. Hydrobiologia. 1977;55:71–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00034807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kazamia E, et al. Mutualistic interactions between vitamin B12-dependent algae and heterotrophic bacteria exhibit regulation. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;14:1466–1476. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hom EFY, Murray AW. Niche engineering demonstrates a latent capacity for fungal-algal mutualism. Science. 2014;345:94–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1253320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramette A, et al. Pseudomonas protegens sp. nov., widespread plant-protecting bacteria producing the biocontrol compounds 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol and pyoluteorin. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2011;34:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hol WH, Bezemer TM, Biere A. Getting the ecology into interactions between plants and the plant growth-promoting bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens. Front. Plant Sci. 2013;4:81. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim CK, Hassan KA, Tetu SG, Loper JE, Paulsen IT. The effect of iron limitation on the transcriptome and proteome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim CK, Hassan KA, Penesyan A, Loper JE, Paulsen IT. The effect of zinc limitation on the transcriptome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;15:702–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loper JE, Gross H. Genomic analysis of antifungal metabolite production by Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2007;119:265–278. doi: 10.1007/s10658-007-9179-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esquenazi E, Yang YL, Watrous J, Gerwick WH, Dorrestein PC. Imaging mass spectrometry of natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:1521–1534. doi: 10.1039/b915674g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graupner K, et al. Imaging mass spectrometry and genome mining reveal highly antifungal virulence factor of mushroom soft rot pathogen. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:13173–13177. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stasulli NM, Shank EA. Profiling the metabolic signals involved in chemical communication between microbes using imaging mass spectrometry. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2016;40:807–813. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuw032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hassan KA, et al. Inactivation of the GacA response regulator in Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 has far-reaching transcriptomic consequences. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;12:899–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wheeler GL, Joint I, Brownlee C. Rapid spatiotemporal patterning of cytosolic Ca2+ underlies flagellar excision in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J. 2008;53:401–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inouye S, et al. Cloning and sequence analysis of cDNA for the luminescent protein aequorin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:3154–3158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun FJ, Hegemann P. Direct measurement of cytosolic calcium and pH in living Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1999;78:199–208. doi: 10.1016/S0171-9335(99)80099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quarmby LM, Hartzell HC. Two distinct, calcium-mediated, signal transduction pathways can trigger deflagellation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J. Cell Biol. 1994;124:807–815. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.5.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bickerton P, Sello S, Brownlee C, Pittman JK, Wheeler GL. Spatial and temporal specificity of Ca2+ signalling in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii in response to osmotic stress. N. Phytol. 2016;212:920–933. doi: 10.1111/nph.14128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gross H, et al. The genomisotopic approach: a systematic method to isolate products of orphan biosynthetic gene clusters. Chem. Biol. 2007;14:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gross H, Loper JE. Genomics of secondary metabolite production by Pseudomonas spp. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:1408–1446. doi: 10.1039/b817075b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yordanova ZP, Woltering EJ, Kapchina-Toteva VM, Iakimova ET. Mastoparan-induced programmed cell death in the unicellular alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Ann. Bot. 2013;111:191–205. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcs264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hilton LK, Meili F, Buckoll PD, Rodriguez-Pike JC, Choutka CP, Kirschner JA, Warner F, Lethan M, Garces FA, Qi J, Quarmby LM. A forward genetic screen and whole genome sequencing identify deflagellation defective mutants in Chlamydomonas, including assignment of ADF1 as a TRP channel. G3. 2016;6:3409–3418. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.034264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knight. H, Trewavas J, Knight MR. Calcium signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana responding to drought and salinity. Plant J. 1997;12:1067–1078. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.12051067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trempel F, et al. Altered glycosylation of exported proteins, including surface immune receptors, compromises calcium and downstream signaling responses to microbe-associated molecular patterns in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16:31. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0718-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Falciatore A, d’Alcala MR, Croot P, Bowler C. Perception of environmental signals by a marine diatom. Science. 2000;288:2363–2366. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vardi A, et al. A stress surveillance system based on calcium and nitric oxide in marine diatoms. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hegemann, P. & Berthold, P. in The Chlamydomonas Sourcebook 2nd edn (eds Harris, E.A., Stern, D. B. & Witman, G. B.) 395–429 (Academic, Oxford, 2009).

- 40.Verret F, Wheeler G, Taylor AR, Farnham G, Brownlee C. Calcium channels in photosynthetic eukaryotes: implications for evolution of calcium-based signaling. N. Phytol. 2010;187:23–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Müller A, et al. Daptomycin inhibits cell envelope synthesis by interfering with fluid membrane microdomains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E7077–E7086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611173113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee B-G, et al. Structures of ClpP in complex with acyldepsipeptide antibiotics reveal its activation mechanism. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:471–479. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma Z, et al. Biosynthesis, chemical structure, and structure-activity relationship of orfamide lipopeptides produced by Pseudomonas protegens and related species. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:382. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim J-D, Kim B, Lee C-G. Alga-lytic activity of Pseudomonas fluorescens against the red tide causing marine alga Heterosigma akashiwo (Raphidophyceae) Biol. Control. 2007;41:296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2007.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Znachor P, Jezberová J. The occurrence of a bloom-forming green alga Pleodorina indica (Volvocales) in the downstream reach of the River Malše (Czech Republic) Hydrobiologia. 2005;541:221–228. doi: 10.1007/s10750-004-5710-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi J-C, Tiedje JM. Biogeography and degree of endemicity of fluorescent Pseudomonas strains in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;66:5448–5456. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.12.5448-5456.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harris, E. H. (ed.). The Chlamydomonas Sourcebook (Academic, San Diego, CA, 1989).

- 48.McBride MJ, et al. Novel features of the polysaccharide-digesting gliding bacterium Flavobacterium johnsoniae as revealed by genome sequence analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:6864–6875. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01495-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Da Silva AC, et al. Comparison of the genomes of two Xanthomonas pathogens with differing host specificities. Nature. 2002;417:459–463. doi: 10.1038/417459a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCarthy LR, Senne JE. Evaluation of acridine orange stain for detection of microorganisms in blood cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1980;11:281–285. doi: 10.1128/jcm.11.3.281-285.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paulsen IT, et al. Complete genome sequence of the plant commensal Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:873–878. doi: 10.1038/nbt1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang JY, et al. Primer on agar-based microbial imaging mass spectrometry. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:6023–6028. doi: 10.1128/JB.00823-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoffmann T, Dorrestein PC. Homogeneous matrix deposition on dried agar for MALDI imaging mass spectrometry of microbial cultures. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2015;26:1959–1962. doi: 10.1007/s13361-015-1241-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sizova I, Fuhrmann M, Hegemann PA. Streptomyces rimosus aphVIII gene coding for a new type phosphotransferase provides stable antibiotic resistance to Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Gene. 2001;277:221–229. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00616-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mus F, Dubini A, Seibert M, Posewitz MC, Grossman AR. Anaerobic acclimation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: anoxic gene expression, hydrogenase induction, and metabolic pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:25475–25486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701415200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berthold P, Schmitt R, Mages W. An engineered Streptomyces hygroscopicus aph 7” gene mediates dominant resistance against hygromycin B in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Protist. 2002;153:401–412. doi: 10.1078/14344610260450136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iliev D, et al. A heteromeric RNA-binding protein is involved in maintaining acrophase and period of the circadian clock. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:797–806. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.085944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beel B, et al. A flavin binding cryptochrome photoreceptor responds to both blue and red light in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2992–3008. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.098947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Knight H, Trewavas AJ, Knight MR. Cold calcium signaling in Arabidopsis involves two cellular pools and a change in calcium signature after acclimation. Plant Cell. 1996;8:489–503. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.3.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request. Plasmids and transgenic lines are available from MM on basis of a Material Transfer Agreement.