Abstract

Hyperopia (farsightedness) is a common and significant cause of visual impairment, and extreme hyperopia (nanophthalmos) is a consequence of loss-of-function MFRP mutations. MFRP deficiency causes abnormal eye growth along the visual axis and significant visual comorbidities, such as angle closure glaucoma, cystic macular edema, and exudative retinal detachment. The Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mouse is used as a pre-clinical animal model of retinal degeneration, and we found it was also hyperopic. To test the effect of restoring Mfrp expression, we delivered a wild-type Mfrp to the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) of Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice via adeno-associated viral (AAV) gene therapy. Phenotypic rescue was evaluated using non-invasive, human clinical testing, including fundus auto-fluorescence, optical coherence tomography, electroretinography, and ultrasound. These analyses showed gene therapy restored retinal function and normalized axial length. Proteomic analysis of RPE tissue revealed rescue of specific proteins associated with eye growth and normal retinal and RPE function. The favorable response to gene therapy in Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice suggests hyperopia and associated refractive errors may be amenable to AAV gene therapy.

Introduction

Hyperopia (farsightedness) is a condition where distant objects can be seen more clearly than nearby ones; and an extreme form of hyperopia is caused by a rare, human genetic disorder known as nanophthalmos. Eyes of nanophthalmos patients are underdeveloped along the visual axis, causing the lens and cornea to be too close to the retina. Secondary complications are common because growth of a full-sized retina must be supported by tissues that only grow to cover less than half their normal area. This crowding in the eye leads to localized slippage between the retinal pigment epithelia (RPE) and the retina, causing deformations that further impair visual activity1. Serious complications can follow, such as angle closure glaucoma, cystic macular edema, and retinal detachment. Although the molecular mechanisms underlying hyperopia are poorly understood, gene therapy to correct a mutation that causes nanophthalmos (and extreme hyperopia) might correct the problem nonetheless. Such gene-therapy correction would have important implications not only for nanophthalmos but potentially also for ordinary cases of near- and farsightedness.

Mutations in human MFRP (membrane-type frizzled-related protein) gene cause hyperopia and nanophthalmos. Often, MFRP-deficient eyes have axial lengths ranging from 15.4 to 16.3 mm, relative to the population average of 23.5 mm, as well as spots of retinal discoloration and reduced electroretinogram (ERG) readings, brought about by the death of photoreceptors (a phenotype typical of nanophthalmos patients). These pathogenic changes may be reversible via gene therapy even without first determining how MFRP regulates eye length. MFRP is expressed in the retinal pigment epithelium; and previous studies showed the RPE regulates ocular growth2. Nanophthalmic eyes have a considerably thicker choroidal vascular bed and scleral coat, structures that provide nutritive and structural support for the retina. Thickening of these tissues is a general feature of axial hyperopia1. When hyperopia is experimentally induced by implanting myopic defocus lenses on the developing eyes of mice, they develop choroidal thickening, decreased scleral growth, and decreased vitreous chamber depth.

Modeling hyperopia in mice has been challenging, but rd6 (Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6) mice could provide an important starting point. In these mice, a 4 bp deletion in the splice donor site of Mfrp exon 4 causes it to be skipped, deleting 58 residues from the MFRP protein. MFRP functions are highly eye-specific so in its absence otherwise healthy mice display white retinal spotting, photoreceptor death, and hyperopia3. This similarity to human disease makes it an ideal model to investigate therapeutic interventions and mechanisms underlying axial eye length. In this study, we tested whether Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice can model hyperopia and whether gene therapy can rescue hyperopia. Using proteomic analysis of RPE-choroid tissue, we identified key proteins that were dysregulated in Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice.

Results

MFRP mutations cause severe human hyperopia

A 5-year old boy was evaluated for posterior microphthalmos. His best-corrected visual acuity was 20/50-3 in the right eye and 20/60 in the left. Cycloplegic refraction revealed high hyperopia of +16.00 bilaterally. Ultrasound showed this was due to shortened eye axial lengths of 16.15 mm on the right, and 16.23 mm on the left (Fig. S1; Table 1). Indirect ophthalmoscopy detected retinal folds in the maculae in both eyes, a feature also detected by optical coherence tomography. There was no retinal pigmentary degeneration. Electroretinography revealed robust scotopic and photopic function, and Goldmann perimetry revealed normal visual fields, together confirming intact photoreceptor function. Genetic testing revealed a homozygous MRFP mutation (IVS10, +5, G > A) at the splice donor site of intron 10.

Table 1.

Axial lengths and mutations of MFRP patients.

| Case | Age | Sex | MRFP mutation | Axial length OD (mm) | Axial length OS (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | M | IVS10, +5, G > A, homozygous | 16.15 | 16.23 |

| 2 | 61 | F | +492, delC, homozygous | 16.89 | 16.89 |

| 3 | 61 | F | +492, delC, homozygous | 17.26 | 16.96 |

| 4 | 19 | M | Frameshift: c.1150dupC/p.His384Profs*8; Missense: c.1615C > T/p.Arg539Cys | 15.00 | 15.06 |

This clinical presentation emphasizes how, in early stages of the disease, MFRP patients suffer visual disability from their hyperopia that is distinct from any retinitis pigmentosa-like phenotype. In contrast, patients with typical retinitis pigmentosa preserve their central macular vision. In MFRP patients, however, the short axial eye length causes structural changes in the macula, such as macular folds, macular edema, and exudative retinal detachment. Thus, despite a physiologically functional macula, their shortened eye length causes macular degenerative changes later. For example, a 19-year old man with a MRFP mutation (frameshift: c.1150dupC/p.His384Profs*8; missense: c.1615C >T/p.Arg539Cys) had high hyperopia (+17.00) with shortened axial eye lengths (Fig. 1A–C). His macula had cystoid changes that reduced his vision to 20/80. Again, there was no intraretinal pigment migration and ERG testing revealed robust photopic function and residual scotopic function. Chronic degenerative changes generally do not develop until late stages of the disease. These late-stage changes are exemplified by two 61-year-old, female twins with an MRFP mutation (+492, delC, homozygous), who had severe hyperopia, and short axial lengths and eventually developed retinal degenerative changes in their maculae that reduced their vision to 20/400 (Fig. S1). Taken together, these clinical findings suggest that the hyperopic phenotype precedes the retinitis pigmentosa phenotype, and imply that early correction of the hyperopic phenotype could improve the secondary effect of short axial eye length, which is the primary contributor to functional vision loss.

Figure 1.

Human Phenotyping. (A) Schematic representation next to an ultrasound scan of a normal eye with normal axial length and a hyperopic eye with reduced axial length (B). Illustrations provided by Lucy Evans (acknowledgements section). (C) Clinical phenotype of a normal eye compared to that of a patient with MFRP-related hyperopia. Infra-red fundus photograph revealed no intra-retinal pigment migration. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) shows cystic degeneration and edema, but photoreceptor nuclei loss in the one of the twins with severe frameshift mutations. (D) Location of known MFRP point mutations span all domains in an MFRP structural model.

Gene therapy for Mfrp-related hyperopia

We performed structural modeling of known MFRP point mutations and found that they were localized across multiple functional domains (Fig. 1D; Figs S2–3; Table S1), lowering the likelihood of developing targeted small-molecule therapy and instead pointing to whole gene replacement. Gene therapy is used to treat human retinal degenerative disease4; and adenoviral vectors can be evaluated in murine preclinical models5,6. We previously showed that gene replacement therapy in Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice reversed histological photoreceptor degeneration and normalized electrical retinal signaling7. While the patient MFRP mutations we identified were structurally-distinct from the rd6 mutation, they are all predicted to result in loss-of-function, similar to the Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mouse model (Table S1). We performed sub-retinal injections of a viral vector carrying the normal mouse Mfrp gene. The vector was composed of the self-complementary Y733F tyrosine capsid mutant AAV2/8 (scAAV). The AAV2/8(Y733F)-CBA-Mfrp were sub-retinally injected into right (OD) eyes of Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice at post-natal day 5 (P5). All left (OS) eyes, in both groups of mice, were maintained as matched controls for experimental analyses.

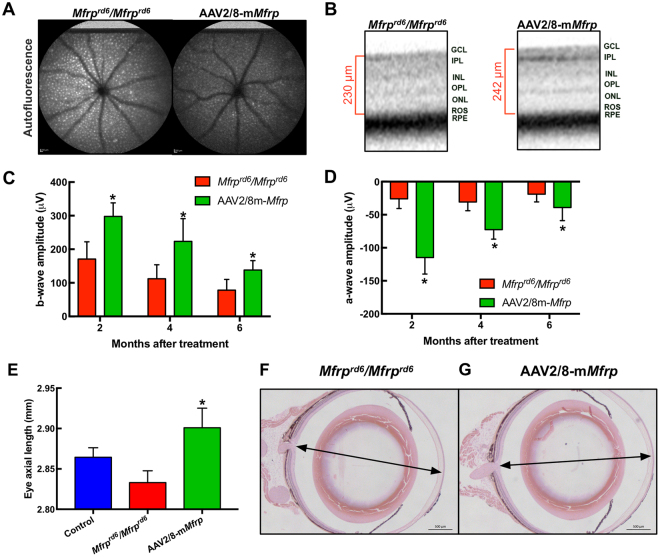

To verify rescue of the Mfrp gene function, retinas were examined using non-invasive human clinical testing, which is highly translatable for human gene therapy (unlike histological analyses)8. Fundus autofluorescence imaging confirmed a reduction in hyper-fluorescent spots, indicating rescue of RPE function (Fig. 2A; p < 0.05). In vivo spectral domain OCT imaging also indicated retinal cell rescue (Fig. 2B). Electroretinography (ERG) confirmed rescue of photoreceptor function. Two months after sub-retinal injection of gene therapy vectors, mice showed significantly increased b-wave and reduced a-wave amplitudes, confirming the function of both rod and cone photoreceptors had improved (Fig. 2C,D; p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Retinal function and axial length recovery after AAV2/8-mMfrp transduction. (A) Fundus autofluorescence (AF) of Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 versus AAV2/8-mMfrp treated eye. A fluorescence standard (an intensity comparison) appears as a bright strip at the top of each image. The AAV2/8-mMfrp eye fluoresced with reduced AF intensity. (B) SD-OCT suggests rescue of retinal cell layers. Representative SD-OCT image shows cell layer thickness was 230 µm in the untreated eye and 242 µm in the treated eye. (C) Quantification of ERG b-wave amplitude shows a significant increase in retinal bipolar cell activity 2-months following gene therapy. Data were analyzed with a pairwise Student’s t-test (p = 0.04). (D) Quantification of ERG a-wave amplitude showing significant increase in photoreceptor cell function 2-months following gene therapy (p = 0.004). (E) Eye axial length was measured using the 50 MHz ultrasound bio-microscope (UBM) probe on an AVISO A/B (Quantel Medical) and reported in millimeters (8 eyes per group). Data were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. AAV2/8-mMfrp mice had a significant increase (average of 0.1 mm) in axial length compared to Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice (p = 0.0334). Histological comparison of Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 (F) and AAV2/8-mMfrp mice (G) eye axial length.

The degree of shortening necessary to produce distorted vision in mice has not been established, but in humans, even 1 mm of shortened length can lead to 20/400 vision (legally blind). Thus, in the much smaller mouse eye, even a small amount of distortion could account for a wide range of effects, from refractive errors to more serious conditions. In our mice, we extended eye length with our gene therapy injections, as shown by ultrasound (Fig. 2E; p < 0.05)8. Wild-type mice and control injection Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice displayed normal and short eye lengths, respectively. Histological fixation of eyes confirmed these results (Fig. 2F,G). In total, gene therapy restored axial length, along with auto-fluorescence and photoreceptor survival in the Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice.

Proteomic analysis of RPE-choroid signaling pathways

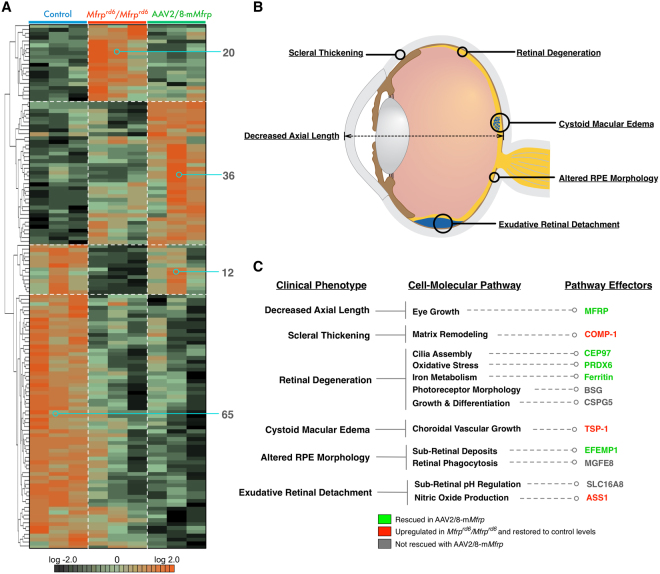

Previously, gene therapy in our Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice restored the normal hexagonal morphology of RPE cells7. We dissected the RPE-choroid tissue from control (C57BL/6), Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6, and AAV2/8-mMfrp mice, and analyzed proteomic content via liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (Fig. S4). Protein intensity data were analyzed with 1-way ANOVA and unbiased hierarchical clustering. A total of 137 proteins were differentially-expressed among the three groups (Fig. 3A; p < 0.05). Based on the hierarchal clustering, proteins were grouped into four categories: proteins upregulated in Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice (Table S2), proteins upregulated in response to AAV injection (Table S3), proteins rescued following gene therapy (Table S4), and proteins not rescued (Table S5). These proteins were queried using pathway analysis (Fig. S5). As a control, we identified 36 proteins upregulated in AAV2/8-mMfrp RPE compared to C57BL/6 (Fig. 3A). These proteins were not present at significant levels in controls, suggesting they were not rescued, but rather expressed as a response to AAV injection. Since sub-retinal injection of AAV2 vectors can induce expression of signaling pathways, we controlled for proteins by subtracting them from our ‘rescued proteins’ list (Table S3; Fig. S5)9.

Figure 3.

Proteomic analysis of Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 and AAV2/8-mMfrp RPE reveal differentially-expressed proteins. (A) Hierarchal clustering of proteins differentially-expressed in Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 and AAV2/8-mMfrp mice compared to B6 controls. Results are represented as a heatmap and display protein levels on a logarithmic scale. A total of 137 proteins were differentially-expressed among the 3 groups (p < 0.05). (B) Pathogenic features of nanophthalmos. Illustration provided by Lucy Evans (acknowledgements section). (C) Correlations between pathogenic features of high hyperopia and the molecular pathways identified in our proteomic analysis.

Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice display photoreceptor cell death and progressive retinal dysfunction. We identified downregulation of protein pathways linked to retinal degeneration: cilia assembly (CEP97), oxidative stress (PRDX6), iron metabolism (Ferritin), and cell growth (BSG and CSPG5; Fig. 3B,C)10–15. Shed rod outer segments accumulate in the sub-retinal space of Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice3,16. This suggests decreased retinal phagocytosis following loss of Mfrp function. Decreased retinal phagocytosis is implicated as a cause of age-related blindness17. MFGE8, a protein involved in retinal phagocytosis, was downregulated in Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 RPE, suggesting that MFRP signaling may be upstream of this process (Fig. 3C). In our previous study, we showed that Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice develop altered RPE morphology, which was reversed by gene therapy (Fig. S3). Levels of EFEMP1, a protein mutated in Malattia Leventinese (MLVT), were rescued following gene therapy. MLVT patients develop retinal degeneration and sub-retinal deposits like Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice18,19. This rescue of EFEMP1 may explain our previous rescue of RPE morphology in Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice.

Our proteomic analysis gave insight into other pathologic features of MFRP-related nanophthalmos. Patients develop scleral thickening, cystoid macular edema, and exudative retinal detachment (Fig. 3B). We identified proteins associated with extracellular matrix remodeling (e.g. COMP-1) in Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice20. This may explain the scleral thickening phenotype. TSP-1 was also highly expressed in Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 RPE. TSP-1 plays a role in regulating choroidal vascular permeability, which may contribute to cystoid macular edema (Fig. 3C)21. We noticed high argininosuccinate synthase-1 (ASS1) levels. ASS1 promotes the formation of nitric oxide, which causes dilation of the retinal vasculature, promoting increased vascular leakage that may cause exudative retinal detachment22.

Discussion

The retinal degeneration phenotype of Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice has been well-described: mice display white retinal spotting and photoreceptor degeneration7. However, descriptions of decreased axial length in these mice have not been described in the literature3,16. To date, there have been no regenerative medicine approaches that could reverse hyperopia in mice. A 1-mm change in the normal 24-mm axial length of human eyes is sufficient to significantly reduce visual acuity. Similar axial length changes in the mouse globe (2.8-mm average in C57BL/6 mice) would also cause significant refractive error23. Our study found an average 0.1-mm improvement in Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mouse eyes treated with gene therapy, which is a fractional change sufficient to produce vision improvement in human eyes. AAV2/8(Y733F)-CBA-Mfrp injections were found to rescue photoreceptor death, normalize retina function, reduce signs of retinal damage, and regulate eye length in adult mice (Fig. 2). These findings are promising in terms of treating the human diseases caused by MFRP mutations. Delivery of gene therapy vectors to the RPE is feasible and could influence eye growth24. With continued successful implementation of ocular gene therapy in patients, MFRP-related nanophthalmos may soon be treatable by gene therapy.

The RPE is thought to play a role in secreting signal molecules to the choroid. Previous studies have exemplified this by showing that imposed myopic defocus (inducing hyperopia) resulted in altered gene expression in the RPE and choroid25. Several molecular pathways are implicated in the development of small eyes, such as Smad4-mediated regulation of retinal Hedgehog and Wnt signaling26. However, the molecular mechanisms of nanophthalmos are poorly understood27. To this end, we used proteomic analysis of RPE-choroid tissue from Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 and AAV-transduced mice to determine differentially-expressed proteins in our mouse model. Using these results, we created a model of molecular pathways affected in MFRP-related nanophthalmos (Fig. 3C). While MFRP mutations have been linked to nanophthalmos and microphthalmia, the function of the MFRP protein is unknown. MFRP contains functional domains that are related to signal transduction, proteolysis, and endocytosis1. The function of these domains and the molecular pathways downstream of MFRP signaling have not been established. Our proteomic analysis allowed us to identify protein pathways that are dysregulated following loss of Mfrp function. These affected pathways provide initial insight into the functions of MFRP beyond the regulation of eye growth.

Methods

Study approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Research at Columbia University, was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki (IRB Protocol AAAF1849). Written informed consent was received from participants prior to inclusion in the study. Color fundus pictures, optical coherence tomography (OCT), and electroretinogram (ERG) analysis were performed on four MFRP-related nanophthalmos patients in the Department of Ophthalmology, Columbia University Medical Center/New York Presbyterian Hospital.

Ethics Statement

The mouse procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Columbia University. Mice were used in accordance with the Statement for the Use of Animals issued by the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, as well as the Policy for the Use of Animals in Neuroscience Research of the Society for Neuroscience.

Phenotypic Ascertainment in humans

The collection of data used in this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Research at Columbia University Medical Center, was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was received from participants prior to inclusion in the study. Clinical examination and testing and genetic testing was performed as previously described28. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) were obtained using Spectralis Heidelberg (Heidelberg, Germany). Genomic DNA from patients was isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes per standard methods. The entire coding sequence and exon-intron boundaries of MFRP (13 exons) were amplified by PCR using pairs of primers that were designed based on the published consensus sequences. Direct sequencing of the PCR-amplified products was analyzed by the Genwize Company (NJ). All MFRP exon data are available at Gene Expression Omnibus (MIM 606227).

Homology modeling of human MFRP

We modeled the MFRP structure using a domain assembly approach: homology models of the cubulin domains (CUB1 and CUB2) were generated using the crystal structure of cubulin (PDB: 3KQ4) as a template with MODELLER 9.14, as described previously28–31. The LDLA1 and LDLA2 domains were generated based off the LDLR structure (PDB: 3P5B). Finally, the frizzled domain (FZ) was modelled using the XWnt8-bound Frizzled-8 structure (PDB: 4F0A) as a template. The individual domains were joined using the homology-modeling protocol in the YASARA 15.7.25 software package to generate a MFRP model. The model was refined with an energy minimization in the YAMBER332 force field followed by a steepest descent minimization and simulated annealing.

Mouse lines and husbandry

Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 and C57BL/6 mice were bred and maintained at the facilities of Columbia University. Animals were housed individually and kept on a light–dark cycle (12 hour–12 hour) before the experiment. Food and water were available ad libitum.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) preparation and transduction into mice

Vectors were constructed and then sent to Penn Vector Corporation for production as previously described7. A total of 1 μl of AAV2/8(Y733F)::mMfrp (1.23e12 genome copy/ml) was transduced into the subretinal space of the right eye of Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice at postnatal day 5, which caused an ideal bleb detachment at the retinal site of the injection. The left eyes of all mice were left untouched and maintained as a control for experimental analyses. Anesthesia and surgery were performed as previously described7.

Non-invasive imaging

Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 (n = 3) and AAV2/8-mMfrp mice (n = 3) were anesthetized as previously described using intraperitoneal ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) injections7. Pupils were dilated to a mean diameter of 2.5 mm with 1% tropicamide and 2.5% phenylephrine 15 minutes before image acquisition. The fundus was aligned as previously described and the retina was pre-exposed at 488 nm in auto-fluorescence mode for 20 seconds to bleach the visual pigment. Detector sensitivity was set at an optimal range that was then used for all auto-fluorescence imaging. Retinas were imaged by SD-OCT using a Heidelberg Spectralis HRA + OCT system (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). Non-correcting contact lenses to prevent corneal desiccation. SD-OCT was taken as horizontal line scan though the central retina 0.5 mm from the optic nerve. Dark-adapted ERGs were elicited with 0.02 and 2 scot-cd.s.m−2 stimuli. Espion ERG Diagnosys equipment (Diagnosys LLC, Lowell, MA) was used for the recordings. Eye axial length was measured using the 50 MHz ultrasound bio-microscope (UBM) probe on an AVISO A/B (Quantel Medical, Bozeman, MT).

Histology of AAV transduced eyes

After subretinal injection of AAV2/8-mMfrp, Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6 mice were sacrificed. Eyes were enucleated and fixed in 1:2x Karnovsky fixative (2% Paraformaldehyde and 1.5% glutaraldehyde) for 24 hours as previously described7. Eyes were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin before being visualized by light microscopy (Leica DM 5000B, Leica Microsystems, Germany).

Proteomic analysis

Proteins were extracted from mouse RPE, precipitated in chloroform-methanol, and dissolved in 0.1% Rapigest detergent in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Shotgun proteomic mass spectrometry-based measurements were performed in triplicate on Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6, AAV2/8::mMfrp, and B6 control RPE. A liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) approach was used for the relative quantitation and simultaneous identification of proteins from all three samples, including triplicate LC/MS/MS chromatograms (technical replicates) collected for each of the three biological replicates. We used Synapt G2 quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (QTOF; Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). The data were analyzed with MSE/IdentityE algorithm (PLGS software Version 2.5 RC9) and Rosetta Elucidator software. Elucidator software detected 383,353 features across 27 LC/MS runs. Identifications were returned on 3,132 proteins with a PLGS score >300 (pass 1 data only) and 4% false discovery rate. Of the 3,132 proteins, 2,089 were represented by two or more peptides and used in further consideration and analysis. Of those 2,089 proteins, there were no missing values among the 27 LC/MS runs (56,403 protein expression quantitative determinations).

Statistical and Bioinformatics analysis

Results were also saved in Excel as.txt format and were uploaded into the Partek Genomics Suite 6.5 software package as previously described33–37. The protein intensity data were normalized to log base 2, and compared using 1-way ANOVA analysis. All proteins with non-significant (p > 0.05) changes were eliminated from the table. The significant values were mapped using the ‘cluster based on significant genes’ visualization function with the standardization option chosen. Reactome Pathway Analysis38 was utilized to determine the most significant cellular pathways affected by the proteins present in Mfrp rd6 /Mfrp rd6, AAV2/8-mMfrp, and B6 control mice RPE.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Lewis Brown, Lucy Evans, Harriet Lloyd, and Diana Colgan for technical assistance. VBM and AGB are supported by NIH grants [R01EY026682, R01EY024665, R01EY025225, R01EY024698, R21AG050437 and P30EY026877]. VBM is supported by The Doris Duke Charitable Foundation #2013103, and Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB). GV is supported by NIH grant T32GM007337. SHT is supported by the NIH [5P30EY019007, R01EY018213, R01EY024698,], NCI [5P30CA013696], RPB, RD-CURE Consortium [C029572], Foundation Fighting Blindness [C-NY05-0705-0312], Joel Hoffman Fund, Professor Gertrude Rothschild Stem Cell Foundation, and the Gebroe Family Foundation.

Author Contributions

V.B.M. initiated and oversaw the study. Study design: S.H.T., A.G.B., and V.B.M. Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: G.V., S.H.T., Y.T.T., C.W.H., A.G., A.H.A., M.M., R.H.S., J.R.S., A.G.B., V.B.M. Critical revision of the manuscript: S.H.T., A.G.B., V.B.M. Statistical analysis: G.V., V.B.M. Obtained funding: S.H.T., A.G.B., and V.B.M. Administrative, technical, and material support: S.H.T., A.G.B., M.M., and V.B.M.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-16275-8.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Stephen H. Tsang, Email: sht2@columbia.edu

Alexander G. Bassuk, Email: alexander-bassuk@uiowa.edu

Vinit B. Mahajan, Email: vinit.mahajan@stanford.edu

References

- 1.Sundin OH, et al. Extreme hyperopia is the result of null mutations in MFRP, which encodes a Frizzled-related protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9553–9558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501451102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rymer J, Wildsoet CF. The role of the retinal pigment epithelium in eye growth regulation and myopia: a review. Vis. Neurosci. 2005;22:251–261. doi: 10.1017/S0952523805223015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawes NL, et al. Retinal degeneration 6 (rd6): a new mouse model for human retinitis punctata albescens. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:3149–3157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sengillo, J. D., Justus, S., Cabral, T. & Tsang, S. H. Correction of Monogenic and Common Retinal Disorders with Gene Therapy. Genes (Basel) 8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Wert KJ, Skeie JM, Davis RJ, Tsang SH, Mahajan VB. Subretinal injection of gene therapy vectors and stem cells in the perinatal mouse eye. J Vis Exp. 2012 doi: 10.3791/4286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wert KJ, Davis RJ, Sancho-Pelluz J, Nishina PM, Tsang SH. Gene therapy provides long-term visual function in a pre-clinical model of retinitis pigmentosa. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013;22:558–567. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, et al. Gene therapy in patient-specific stem cell lines and a preclinical model of retinitis pigmentosa with membrane frizzled-related protein defects. Mol. Ther. 2014;22:1688–1697. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverman RH. High-resolution ultrasound imaging of the eye - a review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;37:54–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01892.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barker SE, et al. Subretinal delivery of adeno-associated virus serotype 2 results in minimal immune responses that allow repeat vector administration in immunocompetent mice. J. Gene Med. 2009;11:486–497. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hori K, et al. Retinal dysfunction in basigin deficiency. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:3128–3133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ochrietor JD, Linser PJ. 5A11/Basigin gene products are necessary for proper maturation and function of the retina. Dev. Neurosci. 2004;26:380–387. doi: 10.1159/000082280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dentchev T, Hahn P, Dunaief JL. Strong labeling for iron and the iron-handling proteins ferritin and ferroportin in the photoreceptor layer in age-related macular degeneration. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1745–1746. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.12.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spektor A, Tsang WY, Khoo D, Dynlacht BD. Cep97 and CP110 suppress a cilia assembly program. Cell. 2007;130:678–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cottet S, et al. Retinal pigment epithelium protein of 65 kDA gene-linked retinal degeneration is not modulated by chicken acidic leucine-rich epidermal growth factor-like domain containing brain protein/Neuroglycan C/ chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 5. Mol. Vis. 2013;19:2312–2320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chidlow G, Wood JP, Knoops B, Casson RJ. Expression and distribution of peroxiredoxins in the retina and optic nerve. Brain Struct Funct. 2016;221:3903–3925. doi: 10.1007/s00429-015-1135-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kameya S, et al. Mfrp, a gene encoding a frizzled related protein, is mutated in the mouse retinal degeneration 6. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:1879–1886. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.16.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nandrot EF, et al. Loss of synchronized retinal phagocytosis and age-related blindness in mice lacking alphavbeta5 integrin. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:1539–1545. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marmorstein LY, McLaughlin PJ, Peachey NS, Sasaki T, Marmorstein AD. Formation and progression of sub-retinal pigment epithelium deposits in Efemp1 mutation knock-in mice: a model for the early pathogenic course of macular degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:2423–2432. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerth C, Zawadzki RJ, Werner JS, Heon E. Retinal microstructure in patients with EFEMP1 retinal dystrophy evaluated by Fourier domain OCT. Eye (Lond.) 2009;23:480–483. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxne T, Heinegard D. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein: a novel marker of cartilage turnover detectable in synovial fluid and blood. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1992;31:583–591. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/31.9.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyajima-Uchida H, et al. Production and accumulation of thrombospondin-1 in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:561–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein IM, Ostwald P, Roth S. Nitric oxide: a review of its role in retinal function and disease. Vision Res. 1996;36:2979–2994. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(96)00017-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park H, et al. Assessment of axial length measurements in mouse eyes. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2012;89:296–303. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31824529e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petit L, Punzo C. Gene therapy approaches for the treatment of retinal disorders. Discov. Med. 2016;22:221–229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feldkaemper MP, Wang HY, Schaeffel F. Changes in retinal and choroidal gene expression during development of refractive errors in chicks. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:1623–1628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, et al. Requirement of Smad4 from Ocular Surface Ectoderm for Retinal Development. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khorram D, et al. Novel TMEM98 mutations in pedigrees with autosomal dominant nanophthalmos. Mol. Vis. 2015;21:1017–1023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moshfegh Y, et al. BESTROPHIN1 mutations cause defective chloride conductance in patient stem cell-derived RPE. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25:2672–2680. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bassuk AG, et al. Structural modeling of a novel CAPN5 mutation that causes uveitis and neovascular retinal detachment. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gakhar L, et al. Small-angle X-ray scattering of calpain-5 reveals a highly open conformation among calpains. J. Struct. Biol. 2016;196:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toral, M. A. et al. Structural modeling of a novel SLC38A8 mutation that causes foveal hypoplasia. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine, 10.1002/mgg3.266 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Krieger E, Darden T, Nabuurs SB, Finkelstein A, Vriend G. Making optimal use of empirical energy functions: force-field parameterization in crystal space. Proteins. 2004;57:678–683. doi: 10.1002/prot.20251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skeie JM, Mahajan VB. Proteomic interactions in the mouse vitreous-retina complex. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahajan VB, Skeie JM. Translational vitreous proteomics. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2014;8:204–208. doi: 10.1002/prca.201300062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skeie JM, Mahajan VB. Proteomic landscape of the human choroid-retinal pigment epithelial complex. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132:1271–1281. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skeie JM, Roybal CN, Mahajan VB. Proteomic insight into the molecular function of the vitreous. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Velez G, et al. Precision Medicine: Personalized Proteomics for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Idiopathic Inflammatory Disease. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:444–448. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.5934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fabregat A, et al. The Reactome pathway Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D481–487. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.