Abstract

Periodontitis is a global health problem and the 6th most common infectious disease worldwide. Porphyromonas gingivalis is considered a keystone pathogen in the disease and is capable of elevating the virulence potential of the periodontal microbial community. Strategies that interfere with P. gingivalis colonization and expression of virulence factor are therefore attractive approaches for preventing and treating periodontitis. We have previously reported that an 11-mer peptide (SAPP) derived from Streptococcus cristatus arginine deiminase (ArcA) was able to repress the expression and production of several well-known P. gingivalis virulence factors including fimbrial proteins and gingipains. Herein we expand and develop these studies to ascertain the impact of this peptide on phenotypic properties of P. gingivalis related to virulence potential. We found that growth rate was not altered by exposure of P. gingivalis to SAPP, while monospecies and heterotypic biofilm formation, and invasion of oral epithelial cells were inhibited. Additionally, SAPP was able to impinge the ability of P. gingivalis to dysregulate innate immunity by repressing gingipain-associated degradation of interleukin-8 (IL8). Hence, SAPP has characteristics that could be exploited for the manipulation of P. gingivalis levels in oral communities and preventing realization of virulence potential.

Introduction

Periodontitis is one of the most common infectious and inflammatory processes of humans and is a leading cause of tooth loss1. Based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the disease affects 47% of adults aged 30 years and older in the United States with different severities2,3. Periodontitis is characterized by destruction of the supporting tissues of the teeth including gingiva, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone, which is caused by uncontrolled host inflammatory responses to the pathogenic oral microbiota. Periodontal diseases and oral bacteria are also physically and epidemiologically associated with severe systemic conditions such as coronary artery disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and diabetes4–6. Although the current treatment for periodontitis significantly improves gingival inflammation, the relief is often temporary and recurrence of the disease is common7,8, due, at least in part, to incomplete elimination of the pathogens9, and failure to restore a health-associated microbial community10.

Dental plaque is a complex multispecies biofilm that is a direct precursor of periodontal diseases. Although several specific oral bacteria are associated with periodontitis, a new model of pathogenesis proposes that polymicrobial synergy among organisms in periodontal microbial communities initiates dysbiotic and destructive immune responses11. In this model, transition from a commensal to a pathogenic microbial community requires the colonization of keystone pathogens such as P. gingivalis. The colonization of oral microbial communities by P. gingivalis depends on its interaction and co-adhesion with antecedent colonizers of oral microbial biofilms. For example, the interaction between P. gingivalis and Streptococcus gordonii, a common inhabitant of oral biofilms, is mediated by both major and minor fimbrial subunit proteins (FimA and Mfa1)12,13. P. gingivalis interspecies interactions subsequently elevate the virulence of the entire microbial community14–17. This phenomenon is evident in murine models, in which low levels of P. gingivalis can initiate alveolar bone loss, but only in the context of a microbial community14. Furthermore, studies using primate models have shown that a gingipain-based vaccine reduces both the number of P. gingivalis cells and total subgingival bacterial load, as well as inhibits bone loss18. Several reports have also documented that the combinations of P. gingivalis and other oral bacteria such as Treponema denticola, Fusobacterium nucleatum or S. gordonii leads to synergistic pathogenicity in animal models19–22. Therefore, inhibiting the colonization and accumulation of P. gingivalis in a polymicrobial community is an attractive strategy for disrupting the transition of a periodontally healthy community into a destructive one.

We have previously reported that arginine deiminase (ArcA) of S. cristatus can repress the expression of the FimA major fimbrial subunit protein in several P. gingivalis strains, including strains expressing fimA types I, II, and III23,24. In an in vitro study, we demonstrated that S. cristatus ArcA significantly inhibited biofilm formation by P. gingivalis 25 and using a mouse model, we found that S. cristatus ArcA can interfere with the colonization and pathogenesis of P. gingivalis 26. More recently, we showed that an 11-mer peptide with the native sequence of ArcA (NIFKKNVGFKK, molecular-weight 1322.62), and theoretical pI 10.48, which we designated as SAPP (Streptococcal-derived Anti-P. gingivalis Peptide), represses the expression of several well-established P. gingivalis virulence-associated genes including fimA, mfa1, rgpA/B, and kgp 27.

In this study, we further tested whether SAPP interferes with virulence-associated phenotypic properties of P. gingivalis. A series of functional assays was performed to assess the impact of SAPP on bacterial growth, biofilm formation, invasion, and gingipain activity, as well as ability of P. gingivalis to manipulate host immune responses. Our data show that SAPP does not affect the growth rate of P. gingivalis strains, but inhibits its ability to form monotypic and heterotypic biofilms, and to invade oral epithelial cells, which are key events of establishing P. gingivalis infection. In addition, arginine- and lysine-specific activities of gingipain were reduced in P. gingivalis cells and its growth media in the presence of SAPP. Our findings demonstrate the potential of SAPP as a lead compound for the development of therapeutic agents designed to inhibit P. gingivalis colonization and pathogenicity.

Results

Effect of SAPP on biofilm formation of P. gingivalis

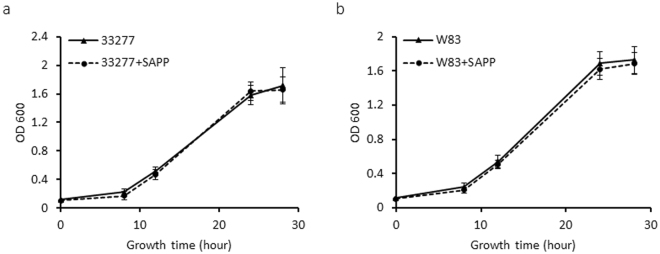

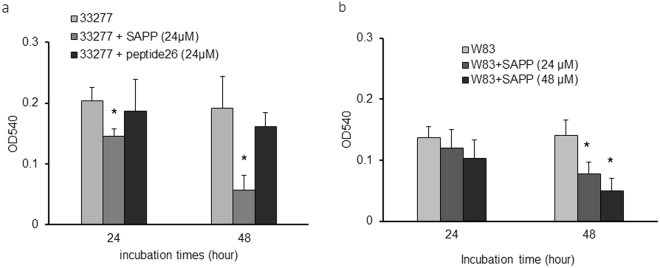

P. gingivalis strains 33277 and W83 obtained from ATCC were selected as representatives of fimbriated, non-encapsulated and non-fimbriated, encapsulated lineages, respectively, to examine alteration of phenotypic properties of P. gingivalis in response to SAPP. As shown in Fig. 1a,b, growth rates of P. gingivalis 33277 or W83 were not significantly changed in the presence of SAPP (24 µM) compared to growth without SAPP. This observation suggests a killing-independent mechanism of SAPP action, which is in agreement with our earlier finding that SAPP represses expression and production of fimbrial proteins and gingipains in P. gingivalis 28. While the predominant niche of P. gingivalis is the subgingival area, the organism also colonizes supragingival plaque and oral mucosal surfaces29. Indeed these sites, which are exposed to the salivary fluid phase, may represent early colonization events. Hence, P. gingivalis strains grown with or without SAPP were then tested for their ability to attach to saliva-covered surfaces. After a 24 h incubation, an approximate 25% decrease of attachment was detected with P. gingivalis 33277 grown with SAPP (24 µM) compared to the control without SAPP (Fig. 2a), while the decrease in attachment reached 70% after 48 h. A control peptide (peptide26 with 11 amino acids located immediately down stream of SAPP) was also tested for its role in biofilm formation of P. gingivalis, and it did not significantly affect the biofilm formation. The effect of W83 on monotypic biofilm formation was also tested with the bacterial cells grown with 24 or 48 µM SAPP. The ability of W83 to form biofilms was lower than that of 33277, and an impact of SAPP on biofilm formation by W83 was not observed after 24 h. However, after 48 h a 33% and 54% reduction in biofilm formation was observed for bacteria grown with 24 or 48 µM SAPP, respectively (Fig. 2b). These results indicate that SAPP can suppress biofilm formation by both 33277 and W83, with a more efficient inhibition occurring with 33277, likely due to the involvement of fimbrial adhesins in biofilm formation by 33277.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the growth curves of P. gingivalis strains grown in the presence or absence of SAPP. P. gingivalis 33277 (a) and W83 (b) were grown in TSB media in the presence or absence of SAPP (24 μM). OD600 was measured over a period of 30 h. Curves are means of triplicate samples, with error bars representing the standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Quantitation of P. gingivalis attachment to a saliva-coated surface. Adherence assays were conducted in 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates. The wells were precoated with human whole saliva and inoculated with P. gingivalis 33277 (a) or W83 (b) grown with SAPP (24 or 48 µM) or control peptide at 37 °C anaerobically. The ability of P. gingivalis to attach and form microcolonies on the surface was quantified by crystal violet staining. Each bar represents the mean ± standard deviation of binding capability from three independent experiments.

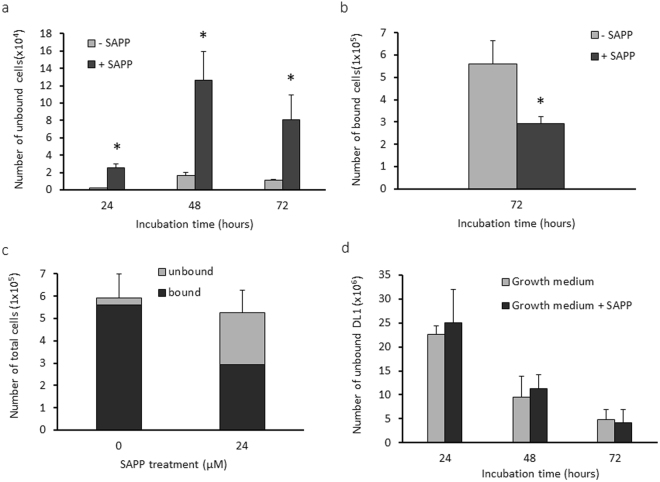

P. gingivalis and S. gordonii dual-species communities are one of the best-documented examples of synergistic oral bacterial interactions. The surface molecules involved in co-adhesion are well characterized and include FimA and Mfa1 of P. gingivalis and streptococcal glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and SspA/B30. We postulated that SAPP could prevent the formation of heterotypic P. gingivalis-S. gordonii biofilms by repressing the expression of fimA and mfa1. To test this, S. gordonii DL1 substrata were first established on saliva-coated wells and reacted with P. gingivalis grown with or without SAPP (24 µM). The amount of P. gingivalis 33277 bound to the S. gordonii DL1 biofilms was determined using qPCR. The number of P. gingivalis grown without SAPP was 2.5-fold higher than that of the bacteria grown with SAPP (Fig. 3). Not surprisingly, binding of P. gingivalis W83, an afrimbriated strain, to S. gordonii DL1 biofilms was not observed (data not shown), which further confirms the role of FimA and Mfa1 fimbriae in the interaction of P. gingivalis and S. gordonii.

Figure 3.

Formation of P. gingivalis 33277-S. gordonii DL1 heterotypic biofilms. S. gordonii DL1 biofilms were established on polystyrene surfaces coated with human whole saliva. P. gingivalis 33277 grown with or without SAPP (24 µM) was reacted with the DL1 biofilms for 4 h. The bound 33277 in the biofilms was quantitated using qPCR. Each bar represents the number of 33277 cells detected in the biofilms. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

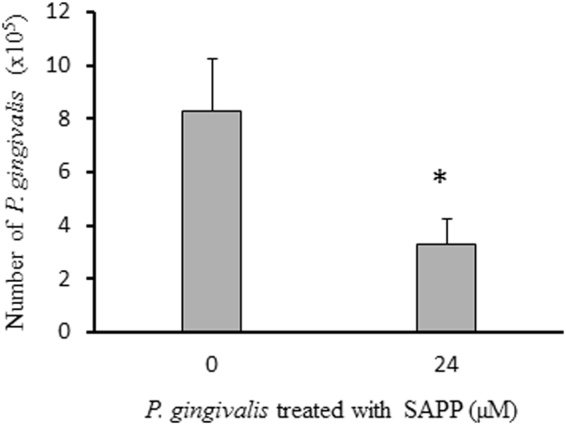

We then tested whether SAPP could reduce the numbers of P. gingivalis cells in established heterotypic biofilms. To do this, we first generated heterotypic biofilms of S. gordonii-P. gingivalis that were grown without SAPP. After the removal of unbound bacteria, SAPP (24 µM) was added. Planktonic P. gingivalis was collected three times in a 24 h interval, and the biofilm was collected after 72 h. The numbers of planktonic or sessile P. gingivalis were determined using qPCR. Levels of planktonic P. gingivalis cells were significantly increased following SAPP treatment (Fig. 4a). Consistent with this, the number of P. gingivalis in the heterotypic biofilms was negatively correlated with that in the planktonic phase, and introduction of SAPP to P. gingivalis-S. gordonii heterotypic biofilms reduced the number of P. gingivalis by approximately 50% after 72 h (Fig. 4b). There was no significant difference in the total P. gingivalis cell numbers with or without SAPP (Fig. 4c), and numbers of S. gordonii in the growth media did not alter in the presence or absence of SAPP (Fig. 4d). These data suggest that SAPP does not affect bacterial viability; rather, it promotes detachment of P. gingivalis cells in the heterotypic biofilms and inhibits their re-entry into the biofilm. Furthermore, SAPP does not impact colonization of the health-related microbiota in this model system.

Figure 4.

Dispersion of P. gingivalis from the heterotypic biofilms by SAPP. P. gingivalis 33277 grown without SAPP was introduced into wells of six-plates covered with S. gordonii DL1 biofilms to form the heterotypic biofilms. SAPP (24 µM) was then added to the wells. The numbers of P. gingivalis cells in the growth media (a), bound on S. gordonii biofilms (b), total number of 33277 in the wells (c), and numbers of S. gordonii in the growth media (d) were determined using qPCR. Numbers of bacterial cells in the wells with or without SAPP were compared, and an asterisk indicates a significant difference in numbers of P. gingivalis cells in the wells in the presence or absence of SAPP (t test, p < 0.05).

Impact of SAPP on intracellular invasion of P. gingivalis

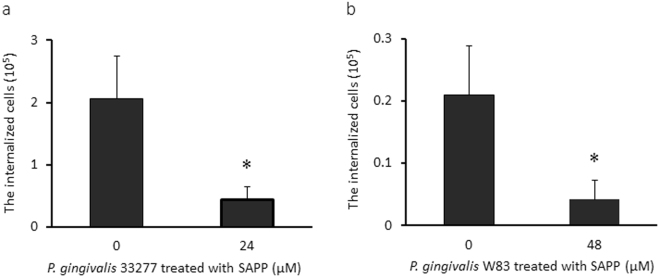

The adherence of P. gingivalis to epithelial cells is mediated primarily by FimA and adhesive domains of gingipains31–34. Adherence subsequently initiates bacterial internalization of host cells35. Since SAPP represses FimA and gingipain production, we postulated that it may also inhibit P. gingivalis invasion of human oral keratinocytes (HOKs). We conducted antibiotic protection assays to compare the invasive ability of P. gingivalis 33277 and W83 grown with or without SAPP. Consistent with previous reports36,37, P. gingivalis W83 was much less efficient than strain 33277 in invading HOKs (Fig. 5a,b). Moreover, the invasion efficiency of 33277 grown with SAPP (24 µM) was reduced by approximate 4.8 fold compared to the control without SAPP, while a 5.2-fold difference in invasion efficiency was observed with W83 grown in the presence or absence of SAPP (48 µM). The differential potencies of SAPP on invasion inhibition of these two strains may due to different adhesins involved in their invasion process. P. gingivalis 33277 may mainly use its long and/or short fimbriae in the process, while W83 does not express these fimbriae and likely depends on other cell surface adhesins such as gingipains38,39.

Figure 5.

SAPP-mediated inhibition of oral keratinocyte invasion by P. gingivalis. Invasion of human oral keratinocytes (HOKs) by P. gingivalis was determined by an antibiotic protection assay. P. gingivalis 33277 (a) or W83 (b) were grown with 24 or 48 µM SAPP, respectively. The number of internalized P. gingivalis cells was represented with means ± SD of triplicates. An asterisk indicates a significant difference between invasive levels observed for P. gingivalis cells grown with or without SAPP (p < 0.05; t test).

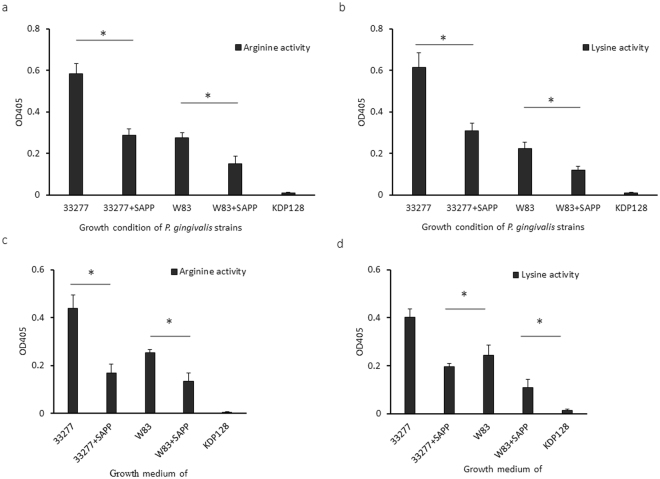

Effect of SAPP on gingipain enzymatic activity

P. gingivalis gingipains are multi-functional proteins with adhesive and catalytic domains. We have previously shown that the expression of genes encoding the arginine- and lysine-specific gingipains was repressed in P. gingivalis grown with SAPP28. Thus, we further tested and compared arginine-specific or lysine-specific activities in P. gingivalis strains grown with or without SAPP. An rgpA −, rgpB −, and kgp − triple mutant (KDP128) was used as a negative control, and as expected, no arginine- or lysine-specific enzyme activities were detected in the mutant (Fig. 6). Cell-associated arginine-specific protease activity of P. gingivalis 33277 grown with SAPP (48 µM) was decreased by 50%, while a 46% reduction was found in W83 under the same experimental conditions, compared to the control without SAPP (Fig. 6a). SAPP inhibited cell-associated lysine-specific protease activity of P. gingivalis 33277 and W83 to a similar degree (Fig. 6b). Rgp and Kgp activities in the growth media of 33277 and W83 were also monitored to determine the levels of secreted gingipains. After exposure to SAPP (48 µM), P. gingivalis 33277 exhibited a greater than 2.5-fold decrease in Rgp activity, and 2-fold less in Kgp activity (Fig. 6c,d). Rgp and Kgp activity in culture supernatants was also 50% lower after W83 was exposed to SAPP (48 µM). Significantly lower protease activities of Rgp and Kgp induced by SAPP may be predicted to reduce the virulence potential of P. gingivalis.

Figure 6.

Comparison of P. gingivalis gingipain protease activities. Rgp or Kgp activities associated with P. gingivalis cells (a,b) or in the culture media of P. gingivalis (c,d) were tested. P. gingivalis 33277 or W83were grown with or without SAPP (48 µM) for 24 h, and the bacterial cells and the growth media were separated by centrifugation. Gingipain activity of KDP128 (an rgpA −, rgpB −, and kgp − mutant) was evaluated, which served as a negative control. Asterisks indicate a statistical difference of protease activity levels in P. gingivalis strains grown with or without SAPP (p < 0.05; t test).

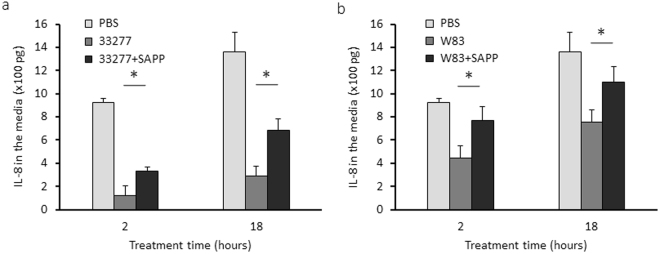

Modulation of IL-8 levels by SAPP

P. gingivalis is known to selectively impair the production of certain cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-8. Thus, we compared the accumulation of IL-8 in the growth media of HOKs exposed to P. gingivalis grown with or without SAPP (48 µM) using an ELISA. The results showed that the ability of P. gingivalis 33277 or W83 to reduce the accumulation of Il-8 was significantly diminished by SAPP (Fig. 7a,b). These data indicate that SAPP has the potential to modulate manipulation of the innate immune response by P. gingivalis.

Figure 7.

Determination of IL-8 level in the grown media of HOKs. HOKs were exposed to P. gingivalis 33277 or W83, at a MOI of 10 for 2 and 18 h, and the culture supernatants and HOKs were collected, respectively. IL-8 levels in the culture media (a,b) were measured using an ELISArray Kit. Each bar represents means of IL-8 concentration, and standard deviations were calculated from three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate statistical difference of IL-8 concentration in the culture supernatants of HOKs treated with P. gingivalis grown with or without SAPP (p < 0.05; t-test).

Discussion

Treatment of chronic and other forms of periodontitis usually involves physical removal of the plaque biofilm sometimes supplemented by systemic or local administration of antibiotics, especially in the cases of severe and refractory manifestations of the disease40–42. While the adjunctive use of antibiotics may improve the results of the mechanical therapy, meta-analyses suggest that the benefits of antibiotic treatment must be balanced against their side effects. Concerns regarding the use of antibiotics include breaking the symbiotic or mutualistic relationships between host and commensal microbiota43, and emerging oral bacterial resistance to antibiotics44. Therefore, targeting specific pathogenic bacteria, rather than non-selectively inhibiting both pathogens and commensal bacteria, has emerged as a strategic goal for maintaining a healthy oral microbiota.

Fimbrial proteins, FimA and Mfa1, and gingipains, RgpA, RgpB, and Kgp, are well-established virulence factors of P. gingivalis. Genes for mfa1 and fimA are present in the genomes of 20 of 21P. gingivalis strains isolated worldwide over a 25 year time period45, and thus far, all tested P. gingivalis strains produce gingipains that are both membrane associated and secreted in soluble form46. The primary role of FimA and Mfa1 is to promote the bacterial attachment to various oral surfaces, which leads to biofilm formation and internalization of epithelial cells47,48. The gingipains include two arginine and one lysine specific cysteine proteinases (RgpA, RgpB, and Kgp)49. Gingipains are multi-functional proteins that have important roles in nutrient acquisition and protein processing, and can also degrade host matrix proteins and immune effector molecules50. Gingipains play an important role in biofilm formation, especially for the strains lacking FimA expression, through the C-terminal adhesive regions of RgpA and Kgp, or through processing profimbrillin51,52. Animal studies with a murine lesion model using gingipain mutants found that gingipains, Kgp in particular, are primary contributors to the formation of skin abscesses53. Moreover, using the same animal model, pretreatment of P. gingivalis with a Kgp inhibitor also decreased bacterial virulence54, which demonstrates an essential role of gingipains in P. gingivalis infection. A previous study by Wilensky et al. also showed that alveolar bone loss was only observed in mice orally infected with RgpA-expressing P. gingivalis strains55. Therefore, inhibition of these P. gingivalis virulence factors has become the focus of therapeutic strategies for prevention and treatment of periodontitis, and a long list of gingipain inhibitors has been discovered, including synthetic compounds, proteins and peptides, and extracts from plants56. Nonetheless, the therapeutic potential of disruption of other pathogenic processes of P. gingivalis is also under investigation. Several molecules derived from marine natural products were identified as inhibitors of P. gingivalis-S. gordonii heterotypic community formation through repression of expression of mfa1 and fimA 57. Other promising biofilm inhibitors are small peptides representing the binding domain (BAR) of S. gordonii SspB, which has been shown to disrupt P. gingivalis-S. gordonii communities and prevent bone loss in a mouse model21,58. One limitation of these inhibitors is that each of them only targets a single virulence factor of P. gingivalis, either a fimbrial protein or gingipains. In this report, we show that SAPP derived from S. cristatus ArcA has a much broader spectrum and is able to impede several virulence factors simultaneously. Such multiplicity of action greatly increases the value of this peptide as a potent inhibitor capable of eliminating P. gingivalis strains expressing virulence factors differentially.

In this study, we have demonstrated that SAPP does not impact growth of P. gingivalis but significantly reduces the numbers of P. gingivalis cells in both monotypic biofilms and P. gingivalis-S. gordonii heterotypic biofilms. A reduction of P. gingivalis cell number may be predicted to lead to a loss of competitive edge and a disruption of polymicrobial synergy. Another significant finding is that SAPP not only inhibits P. gingivalis biofilm formation but also disrupts established biofilms. Although the mechanism is unclear, we speculate that SAPP disrupts attachment and inhibits re-entry of the detached bacteria to the biofilm. The dispersed P. gingivalis cells may be eliminated from the oral cavity due to reduced ability to attach to oral surfaces and to invade host cells. Directly targeting P. gingivalis attachment by SAPP should therefore stabilize a healthy microbiota and maintain homeostasis between the oral microbiota and host immune systems. Hence, it may be sufficient to prevent and treat P. gingivalis associated-periodontitis.

It has been reported that the expression of IL1-α, IL1-β, IL6, IL-8, IL-10, and NF-ƙB is modulated in oral epithelial cells infected with P. gingivalis 59–64. In contrast to many periodontal colonizers that induce expression of IL-8 in gingival epithelial cells, P. gingivalis can inhibit IL-8 production, suggesting a unique role for P. gingivalis in regulating epithelial cell chemokine responses65,66. The ability of P. gingivalis to modulate IL-8 levels could play a pivotal role in initiating periodontitis, as this chemokine is involved in sustaining a healthy periodontium by maintaining a gradient for neutrophil recruitment into the gingival crevice67. The SAPP peptide attenuate the ability of P. gingivalis to reduce the accumulation of IL-8 in epithelial cell culture supernatants, suggesting that SAPP is able to partially restore the impairment of host immunity by P. gingivalis, which may facilitate maintenance of periodontal tissue homeostasis.

In conclusion, we have assessed the inhibitory role of SAPP in biofilm formation, invasion, and gingipain activity of P. gingivalis. We demonstrate that a unique aspect of this peptide is that it efficiently reduced all of these virulence-associated properties of P. gingivalis. It should be pointed out that effective inhibitory activity of SAPP reported here is found in standard culture media and buffers, and it is not known how SAPP works in vivo where SAPP is dissolved in saliva and/or gingival crevicular fluid with wide range of pH68. In addition, more than 200 distinct bacterial species inhabit the human oral cavity of any given individual69,70. Future studies will be designed to determine the efficacy of SAPP under much more complex conditions. Nevertheless, the ability of SAPP to selectively disperse P. gingivalis from dental plaque and attenuate its virulence potential makes it an attractive agent for controlling the composition of microbial communities and maintaining a healthy microbiota.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

P. gingivalis 33277 and W83 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA), and cultured from frozen stocks in either Trypticase soy broth (TSB) or on TSB blood agar plates supplemented with yeast extract (1 mg/ml), hemin (5 μg/ml), and menadione (1 μg/ml), and incubated at 37 °C in an anaerobic chamber (85% N2, 10% H2, and 5% CO2). S. gordonii DL1 was grown in Trypticase peptone broth (TPB) supplemented with 0.5% glucose at 37 °C under aerobic conditions.

Peptide synthesis and activity

SAPP and a control peptide (peptide26 with 11 amino acids located immediately down stream of SAPP) were synthesized by Biomatik (Wilmington, DE) and purified with high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to achieve ≥ 95% purity. The purified peptide was resuspended in nuclease/proteinase-free PBS, aliquoted, and stored at −20 °C.

Monotypic biofilm assay

Attachment of P. gingivalis to saliva-coated surfaces was evaluated as described previously71. Briefly, P. gingivalis strains were grown to mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.8) and collected by centrifugation. Bacterial cells (108) were resuspended in TSB, transferred to the wells of a 96-well polystyrene plate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) that were precoated with human whole saliva that was diluted 2 times with PBS, and incubated at 37 °C. After washing, the biofilms were stained with 1% crystal violet and destained with 95% ethanol. The absorbance of the ethanol de-staining solution at 540 nm was then determined with the Ultrospec 2100 Pro spectrophotometer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ).

Heterotypic biofilm assay

Heterotypic biofilms of P. gingivalis and S. gordonii were generated on a polystyrene six-well plate. S. gordonii DL1 cells (2 × 109) were first incubated aerobically in saliva-coated wells at 37 °C for 3 h, and the unbound cells were removed by washing with PBS three times. P. gingivalis cells (2 × 109) grown in TSB with or without SAPP were collected, re-suspended in ¼ TSB (1:3 TSB and PBS), added to the wells containing streptococcal biofilms, and incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 4 h. The number of sessile P. gingivalis in S. gordonii biofilms was determined using qPCR. The bacterial cells were lysed with lysis solution (solution A; Invitrogen, Waltham, MA), and DNA was extracted using an Easy-DNA kit (Invitrogen). P. gingivalis cells in the biofilms were enumerated using a QuantiTect SYBR green PCR kit with 16S rRNA gene primers of P. gingivalis 25. Standards used to determine numbers of P. gingivalis in the heterotypic biofilms were prepared using genomic DNA from P. gingivalis 33277. A fresh culture of 33277 was serially diluted in PBS and plated on TSB plates to obtain the colony forming units (CFUs) per milliliter for each dilution.

To determine whether SAPP promotes the release of P. gingivalis cells from the heterotypic biofilms and/or inhibits their re-entry, a modified biofilm assay was conducted. P. gingivalis grown without SAPP was first added to wells of six-well polystyrene plates containing S. gordonii DL1 and incubated for 4 h. After removing the unbound P. gingivalis, fresh ½ TSB (1:1 TSB and PBS) containing SAPP and gentamicin (50 μg/ml) was then added and the plates were incubated with gentle shaking under anaerobic conditions. Planktonic P. gingivalis were collected at three 24 h intervals, while the sessile bacterial cells were collected at the 72-h time point. Bacterial DNA was purified using an Easy-DNA kit (Invitrogen), and the P. gingivalis cells were quantitated using qPCR.

Arg- and Lys-specific proteinase activities

Gingipain activities of P. gingivalis whole cells were measured in 96-well plates as described previously53,72. P. gingivalis 33277 or W83 were anaerobically grown in 2 ml TSB with or without SAPP to stationary phase (OD600 = 1.2). Bacterial cells and growth media were separated by centrifugation, and the cells were re-suspended in 2 ml ice-cold TC150 buffer (pH 8.0, 5 mM cysteine, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, and 5 mM CaCl2). The P. gingivalis cell suspension (2.5 × 106 cells in 2.5 µl) or 100 µl of P. gingivalis growth media were resuspended in TC150 buffer and mixed with 100 µl substrate solution (2 mM N-a-benzoyl-Arg-p-nitroanilide (BApNA) or N-(p-tosyl)-Gly-Pro-Lys 4-nitroanilide ace-tate salt (GPK-NA), 30% isopropanol (vol/vol), 400 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 100 mM NaCl, and 2 mM cysteine) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The reaction solutions were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h, and the absorbance at 405 nm was measured by a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Bacterial invasion assay

The invasive ability of P. gingivalis was determined using an antibiotic protection assay73. P. gingivalis strains were grown in TSB for 16 h with or without SAPP to reach mid-log phase. The bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation. Human oral keratinocytes (HOKs, 5 × 105) (ScienCell Research Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA) were seeded in a six-well plate. After reaction with P. gingivalis 33277 or W83 for 1 h, the HOKs were washed with PBS to remove unbound bacteria and then continually cultured for another 4 h in the presence of antibiotics gentamicin (300 µg/ml) and metronidazole (200 µg/ml) to eliminate extracellular bacteria. The HOKs were then washed three times with PBS and lysed with sterile distilled dH2O. The internalized bacteria were plated on TSB blood agar plates. The plates were incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 7 days, and CFUs of P. gingivalis were enumerated.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISA was performed using a human IL-8 Single Analyte ELISArray Kit (Qiagen, Redwood City, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. HOKs (1 × 105) were exposed to P. gingivalis (1 × 106) grown with or without SAPP for 2 and 18 h. The culture media of HOKs were collected and analyzed by ELISA. IL-8 was quantitated using a standard curve of the cytokine.

Statistical analyses

A Student’s t-test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences in functions and growth rates of P. gingivalis strains grown in the presence or absence of SAPP. A p < 0.05 was considered significant. All assays were performed with three biological replicates.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants DE022428 and 025332 (HX) and DE012505 and DE023193 (RJL) from NIDCR, and by MD007593 and MD007586 from NIMHD. The project described was also supported by NCRR grant UL1 RR024975, which is now mediated by the NCATS (2 UL1 TR000445). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We thank the Meharry Office for Scientific Editing and Publications for scientific editing support (S21MD000104).

Author Contributions

H.X. and R.J.L. designed the project. M.H.H. and H.X. performed the experiments. H.X. and R.J.L. analyzed the data. H.X. and R.J.L. wrote the main manuscript text. All the authors contributed to the discussion and provided comments on the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-16522-y.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Eke, P. I., Dye, B. A., Wei, L., Thornton-Evans, G. O. & Genco, R. J. Prevalence of Periodontitis in Adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res 91, 914–920, 10.1177/0022034512457373. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Eke PI, et al. Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. Journal of dental research. 2012;91:914–920. doi: 10.1177/0022034512457373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eke PI, et al. Update on Prevalence of Periodontitis in Adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. Journal of periodontology. 2015;86:611–622. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajishengallis G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2015;15:30–44. doi: 10.1038/nri3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linden GJ, Lyons A, Scannapieco FA. Periodontal systemic associations: review of the evidence. Journal of periodontology. 2013;84:S8–S19. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.1340010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar PS. Oral microbiota and systemic disease. Anaerobe. 2013;24:90–93. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher S, et al. Progression of periodontal disease in a maintenance population of smokers and non-smokers: a 3-year longitudinal study. Journal of periodontology. 2008;79:461–468. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Claffey N, Polyzois I, Ziaka P. An overview of nonsurgical and surgical therapy. Periodontology 2000. 2004;36:35–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2004.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uzel NG, et al. Microbial shifts during dental biofilm re-development in the absence of oral hygiene in periodontal health and disease. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2011;38:612–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abusleme L, et al. The subgingival microbiome in health and periodontitis and its relationship with community biomass and inflammation. The ISME journal. 2013;7:1016–1025. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Molecular oral microbiology. 2012;27:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2012.00663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demuth DR, Irvine DC, Costerton JW, Cook GS, Lamont RJ. Discrete protein determinant directs the species-specific adherence of Porphyromonas gingivalis to oral streptococci. Infection and immunity. 2001;69:5736–5741. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5736-5741.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park Y, et al. Short fimbriae of Porphyromonas gingivalis and their role in coadhesion with Streptococcus gordonii. Infection and immunity. 2005;73:3983–3989. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.3983-3989.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajishengallis G, et al. Low-abundance biofilm species orchestrates inflammatory periodontal disease through the commensal microbiota and complement. Cell host & microbe. 2011;10:497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. Breaking bad: manipulation of the host response by Porphyromonas gingivalis. European journal of immunology. 2014;44:328–338. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajishengallis G, Darveau RP, Curtis MA. The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 2012;10:717–725. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darveau RP, Hajishengallis G, Curtis MA. Porphyromonas gingivalis as a potential community activist for disease. Journal of dental research. 2012;91:816–820. doi: 10.1177/0022034512453589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page RC, et al. Immunization of Macaca fascicularis against experimental periodontitis using a vaccine containing cysteine proteases purified from Porphyromonas gingivalis. Oral microbiology and immunology. 2007;22:162–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2007.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nahid MA, Rivera M, Lucas A, Chan EK, Kesavalu L. Polymicrobial infection with periodontal pathogens specifically enhances microRNA miR-146a in ApoE-/- mice during experimental periodontal disease. Infection and immunity. 2011;79:1597–1605. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01062-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polak D, et al. Mouse model of experimental periodontitis induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis/Fusobacterium nucleatum infection: bone loss and host response. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2009;36:406–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daep CA, Novak EA, Lamont RJ, Demuth DR. Structural dissection and in vivo effectiveness of a peptide inhibitor of Porphyromonas gingivalis adherence to Streptococcus gordonii. Infection and immunity. 2011;79:67–74. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00361-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verma RK, et al. Virulence of major periodontal pathogens and lack of humoral immune protection in a rat model of periodontal disease. Oral diseases. 2010;16:686–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie H, et al. Intergeneric communication in dental plaque biofilms. Journal of bacteriology. 2000;182:7067–7069. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.24.7067-7069.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang BY, Wu J, Lamont RJ, Lin X, Xie H. Negative correlation of distributions of Streptococcus cristatus and Porphyromonas gingivalis in subgingival plaque. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2009;47:3902–3906. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00072-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu J, Xie H. Role of arginine deiminase of Streptococcus cristatus in Porphyromonas gingivalis colonization. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2010;54:4694–4698. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00284-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie H, Hong J, Sharma A, Wang BY. Streptococcus cristatus ArcA interferes with Porphyromonas gingivalis pathogenicity in mice. J Periodontal Res. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2012.01469.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho MH, Lamont RJ, Xie H. Identification of Streptococcus cristatus peptides that repress expression of virulence genes in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Scientific reports. 2017;7:1413. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01551-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meng-Hsuan H, R. J. L. A. H. X. Identification of Streptococcus cristatus peptides that repress expression of virulence genes in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Sci Rep. (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Griffen AL, Becker MR, Lyons SR, Moeschberger ML, Leys EJ. Prevalence of Porphyromonas gingivalis and periodontal health status. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1998;36:3239–3242. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3239-3242.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamont RJ, Hajishengallis G. Polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis in inflammatory disease. Trends in molecular medicine. 2015;21:172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakagawa I, et al. Functional differences among FimA variants of Porphyromonas gingivalis and their effects on adhesion to and invasion of human epithelial cells. Infection and immunity. 2002;70:277–285. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.277-285.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yilmaz O, Watanabe K, Lamont RJ. Involvement of integrins in fimbriae-mediated binding and invasion by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Cellular microbiology. 2002;4:305–314. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen T, Nakayama K, Belliveau L, Duncan MJ. Porphyromonas gingivalis gingipains and adhesion to epithelial cells. Infection and immunity. 2001;69:3048–3056. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3048-3056.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen T, Duncan MJ. Gingipain adhesin domains mediate Porphyromonas gingivalis adherence to epithelial cells. Microbial pathogenesis. 2004;36:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tribble GD, Lamont RJ. Bacterial invasion of epithelial cells and spreading in periodontal tissue. Periodontology 2000. 2010;52:68–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suwannakul S, Stafford GP, Whawell SA, Douglas CW. Identification of bistable populations of Porphyromonas gingivalis that differ in epithelial cell invasion. Microbiology. 2010;156:3052–3064. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.038075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mantri CK, Chen C, Dong X, Goodwin JS, Xie H. Porphyromonas gingivalis-mediated Epithelial Cell Entry of HIV-1. Journal of dental research. 2014;93:794–800. doi: 10.1177/0022034514537647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stathopoulou PG, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis induce apoptosis in human gingival epithelial cells through a gingipain-dependent mechanism. BMC microbiology. 2009;9:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamont RJ, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis invasion of gingival epithelial cells. Infection and immunity. 1995;63:3878–3885. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.3878-3885.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walters J, Lai PC. Should Antibiotics Be Prescribed to Treat Chronic Periodontitis? Dental clinics of North America. 2015;59:919–933. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santos RS, et al. The use of systemic antibiotics in the treatment of refractory periodontitis: A systematic review. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2016;147:577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jepsen K, Jepsen S. Antibiotics/antimicrobials: systemic and local administration in the therapy of mild to moderately advanced periodontitis. Periodontology 2000. 2016;71:82–112. doi: 10.1111/prd.12121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blaser MJ, Falkow S. What are the consequences of the disappearing human microbiota? Nature reviews. Microbiology. 2009;7:887–894. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Villedieu A, et al. Prevalence of tetracycline resistance genes in oral bacteria. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2003;47:878–882. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.3.878-882.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dashper SG, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis Uses Specific Domain Rearrangements and Allelic Exchange to Generate Diversity in Surface Virulence Factors. Frontiers in microbiology. 2017;8:48. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mikolajczyk-Pawlinska J, et al. Genetic variation of Porphyromonas gingivalis genes encoding gingipains, cysteine proteinases with arginine or lysine specificity. Biological chemistry. 1998;379:205–211. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1998.379.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshimura F, Murakami Y, Nishikawa K, Hasegawa Y, Kawaminami S. Surface components of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Journal of periodontal research. 2009;44:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2008.01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lamont RJ, Jenkinson HF. Life below the gum line: pathogenic mechanisms of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews: MMBR. 1998;62:1244–1263. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1244-1263.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Curtis MA, et al. Molecular genetics and nomenclature of proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Journal of periodontal research. 1999;34:464–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1999.tb02282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Potempa J, Banbula A, Travis J. Role of bacterial proteinases in matrix destruction and modulation of host responses. Periodontology 2000. 2000;24:153–192. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2000.2240108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kadowaki T, et al. Arg-gingipain acts as a major processing enzyme for various cell surface proteins in Porphyromonas gingivalis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:29072–29076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.29072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shi Y, et al. Genetic analyses of proteolysis, hemoglobin binding, and hemagglutination of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Construction of mutants with a combination of rgpA, rgpB, kgp, and hagA. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:17955–17960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Brien-Simpson NM, et al. Role of RgpA, RgpB, and Kgp proteinases in virulence of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50 in a murine lesion model. Infection and immunity. 2001;69:7527–7534. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7527-7534.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Curtis MA, et al. Attenuation of the virulence of Porphyromonas gingivalis by using a specific synthetic Kgp protease inhibitor. Infection and immunity. 2002;70:6968–6975. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6968-6975.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilensky A, Polak D, Houri-Haddad Y, Shapira L. The role of RgpA in the pathogenicity of Porphyromonas gingivalis in the murine periodontitis model. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2013;40:924–932. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Olsen, I. & Potempa, J. Strategies for the inhibition of gingipains for the potential treatment of periodontitis and associated systemic diseases. Journal of oral microbiology6, 10.3402/jom.v6.24800 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Wright CJ, Wu H, Melander RJ, Melander C, Lamont RJ. Disruption of heterotypic community development by Porphyromonas gingivalis with small molecule inhibitors. Molecular oral microbiology. 2014;29:185–193. doi: 10.1111/omi.12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daep CA, James DM, Lamont RJ, Demuth DR. Structural characterization of peptide-mediated inhibition of Porphyromonas gingivalis biofilm formation. Infection and immunity. 2006;74:5756–5762. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00813-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ji S, Kim Y, Min BM, Han SH, Choi Y. Innate immune responses of gingival epithelial cells to nonperiodontopathic and periodontopathic bacteria. Journal of periodontal research. 2007;42:503–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2007.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Milward MR, et al. Differential activation of NF-kappaB and gene expression in oral epithelial cells by periodontal pathogens. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2007;148:307–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stathopoulou PG, Benakanakere MR, Galicia JC, Kinane DF. The host cytokine response to Porphyromonas gingivalis is modified by gingipains. Oral microbiology and immunology. 2009;24:11–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2008.00467.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stathopoulou PG, Benakanakere MR, Galicia JC, Kinane DF. Epithelial cell pro-inflammatory cytokine response differs across dental plaque bacterial species. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2010;37:24–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kebschull M, Papapanou PN. Periodontal microbial complexes associated with specific cell and tissue responses. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2011;38(Suppl 11):17–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Milward, M. R., Chapple, I. L., Carter, K., Matthews, J. B. & Cooper, P. R. Micronutrient modulation of NF-kappaB in oral keratinocytes exposed to periodontal bacteria. Innate immunity, 10.1177/1753425912454761 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Darveau RP, Belton CM, Reife RA, Lamont RJ. Local chemokine paralysis, a novel pathogenic mechanism for Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infection and immunity. 1998;66:1660–1665. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1660-1665.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hasegawa Y, et al. Role of Porphyromonas gingivalis SerB in gingival epithelial cell cytoskeletal remodeling and cytokine production. Infection and immunity. 2008;76:2420–2427. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00156-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tonetti MS, Imboden MA, Lang NP. Neutrophil migration into the gingival sulcus is associated with transepithelial gradients of interleukin-8 and ICAM-1. Journal of periodontology. 1998;69:1139–1147. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Galgut PN. The relevance of pH to gingivitis and periodontitis. Journal of the International Academy of Periodontology. 2001;3:61–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Keijser BJ, et al. Pyrosequencing analysis of the oral microflora of healthy adults. Journal of dental research. 2008;87:1016–1020. doi: 10.1177/154405910808701104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bik EM, et al. Bacterial diversity in the oral cavity of 10 healthy individuals. The ISME journal. 2010;4:962–974. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.O’Toole GA, Kolter R. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Molecular microbiology. 1998;28:449–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dashper SG, et al. Lactoferrin inhibits Porphyromonas gingivalis proteinases and has sustained biofilm inhibitory activity. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2012;56:1548–1556. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05100-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xie H, Cai S, Lamont RJ. Environmental regulation of fimbrial gene expression in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infection and immunity. 1997;65:2265–2271. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2265-2271.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.