Abstract

The presence of splicing sequence variants in genes responsible for sex development in humans may compromise correct biosynthesis of proteins involved in the normal development of gonads and external genitalia. In a cohort of Brazilian patients, we identified mutations in HSD17B3 and SRD5A2 which are both required for human sexual differentiation. A number of these mutations occurred within regions potentially critical for splicing regulation. Minigenes were used to validate the functional effect of mutations in both genes. We evaluated the c.277 + 2 T > G mutation in HSD17B3, and the c.544 G > A, c.548-44 T > G and c.278delG mutations in SRD5A2. We demonstrated that these mutations altered the splicing pattern of these genes. In a genomic era these results illustrate, and remind us, that sequence variants within exon-intron boundaries, which are primarily identified for diagnostic purposes and have unknown pathogenicity, need to be assessed with regards to their impact not only on protein expression, but also on mRNA splicing.

Introduction

Discovered in the late 1970s, the splicing process is a crucial step in the biogenesis of eukaryotic mRNA1,2. The chemistry of the splicing reaction is mediated by the spliceosome, a ribonucleoprotein complex assembled from five subcomplexes called snRNP’s (U1snRNP, U2, U4, U5 and U6)3 which interact with specific sequences at the exon/intron boundaries to direct intron excision and exon ligation to produce the mature mRNA4.

The first core splicing signal sequence is the 5′ splice site, which is present at the 5′ end of the intron and includes a universally conserved GU dinucleotide (the donor site AG/GURAGU, where R is a purine). The second consensus sequence is the 3′ splice site, located at the 3′ end of the intron and defined by three conserved elements: the branch point (composed of the sequence YNYURAC, where Y is a pyrimidine), polypyrimidine tract, and terminal AG at the extreme 3′ end of the intron (the acceptor site YAG/RNNN)5,6.

Auxiliary cis-elements, known as exonic and intronic splicing enhancers (ESEs and ISEs) and silencers (ESSs and ISSs), are essential sequences which increase splicing fidelity7. Many ESEs and ISEs contain binding sites for members of the SR protein family. SR proteins are often involved in positive regulation of the splicing process and promote early spliceosomal complex assembly8. Whereas, the best characterized splicing silencers are recognized by heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs)9.

Cis-acting mutations can disrupt the use of essential splice sites resulting in loss of gene expression or activation of alternative splice sites, which force the expression of alternative mRNA isoforms. Importantly, if the expression of alternative splicing isoforms occurs at an inappropriate developmental stage this may result in disease10. Alterations in the spliceosome machinery and point mutations located at intron-exon boundaries can result in severe changes to the splicing processe and thus impact on the appearance of disease11. It has been shown that 15–62% of all splicing mutations result in the expression of aberrant mRNA products that directly result in disease12–14.

In the present study we have evaluated the effect of mutations within two genes critical for human sexual development: HSD17B3 and SRD5A2. These genes are involved in the biosynthesis of steroid hormones, testosterone (T) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) respectively. The HSD17B3 gene produces the 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 3 (17beta-HSD3) enzyme, which catalyzes the synthesis of T from androstenedione (A). The SRD5A2 gene encodes the 5alpha-reductase type 2 enzyme, which converts T to DHT, a more active metabolite15,16. Individuals with 17beta-HSD3 or 5alpha-reductase type 2 deficiencies will experience undermasculinization with predominantly female external genitalia or may present hypospadias. They are often raised as girls despite the fact that they carry a 46,XY karyotype. Deficiencies in either 17beta-HSD3 or 5alpha-reductase type 2 enzymes are inherited as autosomal recessive disorders17,18. A limited number of mutations within 5′ and 3′ splice sites have been described for these genes19–22.

The aim of this study was to functionally evaluate the effect of sequence variants of unknown significance (VUS) within these genes which were predicited to affect splicing: c.277 + 2 T > C in HSD17B3, and c.278delG, c.183-44 T > G and c.544 G > A in SRD5A2. For this purpose we developed hybrid minigenes containing either wild-type (WT) DNA sequences or DNA from patients carrying the sequence variants. Assessment of the splicing pattern of either WT or mutant minigenes enabled us to determine the effect of the VUS on the splicing mechanism.

Results

To functionally validate whether the identified sequence variants disrupted splicing, minigenes containing the mutation of interest or the WT sequence were constructed. Each minigene construct was transfected, in triplicate, into HEK-293 cells. 48 hours later cells were harvested, RNA purified and the effect on splicing determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR and sequencing.

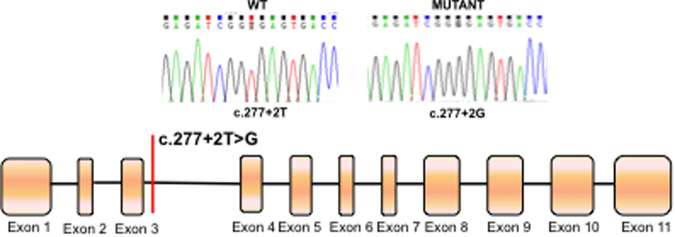

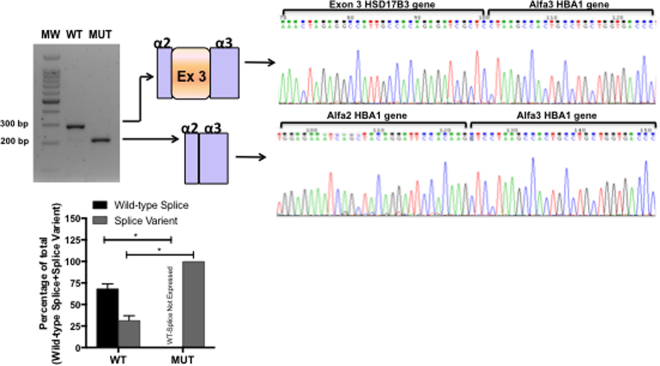

The c.277 + 2 T > G HSD17B3 mutation located in the 5′ splice site of intron 3 (Fig. 1) was previously described in compound heterozygosis with the c.277 + 4 A > T mutation in a 46,XY female patient23. As aberrant splicing had already been described for the c.277 + 4 A > T HSD17B3 mutation19, we investigated the affect of the c.277 + 2 T > G mutation on splicing. RT-PCR results showed that the c.277 + 2 T > G mutation enhanced skipping of exon 3 compared to WT (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram showing the location of the c.277 + 4 A > T mutation in the HSD17B3 gene. Boxes represent exons, lines represent introns.

Figure 2.

RT-PCR results from transfections of wild-type HSD17B3 or c.277 + 2 T > G HSD17B3 minigenes. A representative agarose gel (n = 3) showing the results of RT-PCR of wild-type (WT) and mutant (MUT) minigene splicing is shown and quantified for the accompanying graph. Schematic diagrams identifying wild-type splicing (293 bp) and exon 3 skipping (217 bp) are shown. The panel on the right shows electropherograms of cDNA splicing isoforms generated from wild-type and mutant minigenes. The histogram shows the relative percentage expression of each isoform calculated against total intensity of the bands representing each isoform. Student t test analysis shown; *p < 0.01.

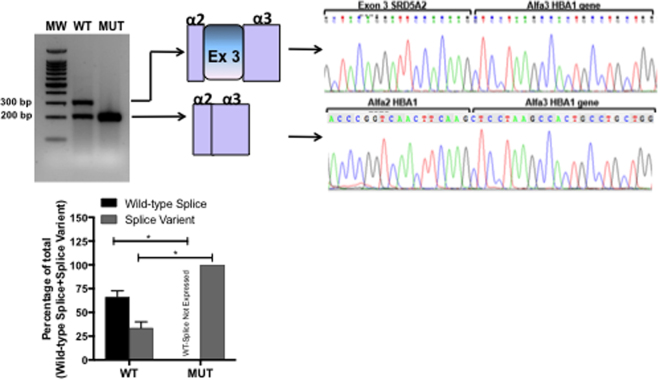

The c.544 G > A SRD5A2 mutation is located in the last nucleotide of exon 3 (5′ splice site) (Fig. 3). The DNA used for this assay was obtained from a homozygous 46,XY female patient described elsewhere24. Assessment of c.544 G > A minigene splicing showed that this mutation promoted skipping of exon 3 (Fig. 4), which may result in an alteration of 5α-reductase type 2 protein expression and lead to the disease phenotype.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram showing the location of c.278delG, c.183-44 T > G and c.544 G > A mutations in the SRD5A2 gene. Boxes represent exons, lines represent introns.

Figure 4.

RT-PCR results from transfections of wild-type SRD5A2 or c.544 G > A SRD5A2 minigenes. A representative agarose gel (n = 3) showing the results of RT-PCR of wild-type (WT) and mutant (MUT) minigene splicing is shown and quantified for the accompanying graph. Schematic diagrams identifying wild-type splicing (317 bp) and exon 3 skipping (217 bp) are shown. The panel on the right shows electropherograms of cDNA splicing isoforms generated from wild-type and mutant minigenes. The histogram shows the relative percentage expression of each isoform calculated against total intensity of the bands representing each isoform. Student t test analysis shown; *p < 0.01.

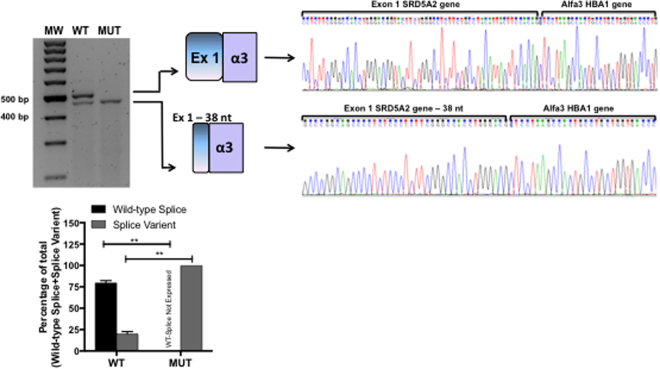

The c.278delG SRD5A2 mutation is located within the 5′ splice site of exon 1 (Fig. 3). This mutation was identified in compound heterozygosis with p.Gly196Ser21 in a 46,XY patient with ambiguous genitalia24. Analysis of the amino acid sequence showed that the c.278delG mutation resulted in a frameshift that generates a premature stop codon at position 121 (p.Val81Leufs*121). Additionally, RT-PCR and sequencing results showed that c.278delG promoted the use of a cryptic 5′ splice site at c.243 resulting in a transcript with a 38-nucleotide deletion at the 3′ end of exon 1 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

RT-PCR results from transfections of wild-type SRD5A2 or c.278delG SRD5A2 minigenes. A representative agarose gel (n = 3) showing the results of RT-PCR of wild-type (WT) and mutant (MUT) minigene splicing is shown and quantified for the accompanying graph. Schematic diagrams identifying wild-type splicing (479 bp) and a transcript with the deletion of 38 nucleotides (441 bp) are shown. The panel on the right shows electropherograms of cDNA splicing isoforms generated from wild-type and mutant minigenes. The histogram shows the relative percentage expression of each isoform calculated against total intensity of the bands representing each isoform. Student t test analysis shown; **P ≤ 0.001.

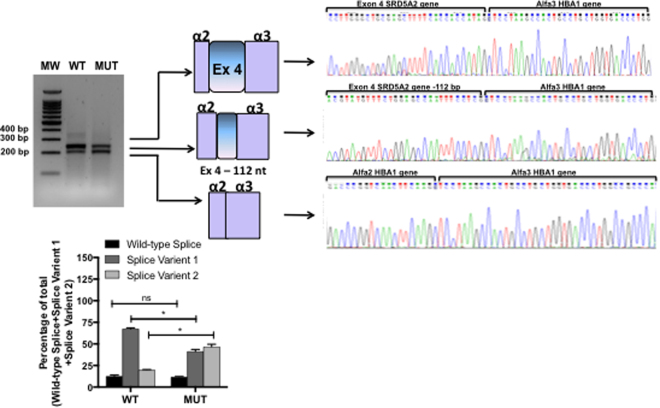

We evaluated the SRD5A2 sequence variant c.548-44 T > G, located at the 3′ splice site of intron 3 (Fig. 3). This mutation was identified in a heterozygous 46,XY DSD patient that had palpable gonads in the labioscrotal folds and male genitalia. RT-PCR results showed that both WT and mutant minigenes produced three transcripts. Sequencing identified that they corresponded to: the WT transcript sequence (369 bp); a transcript with deletion of 112 nucleotides at the 3′ splice site of exon 4 (Splice Variant 1 = 257 bp); and a transcript with exon 4 skipping (Splice Variant 2 = 217 bp). The band intensity of the 3 transcripts differed between the WT and mutant c.548-44 T > G minigenes. In the WT minigene Splice Variant 1 was most prevalent (66%), whereas the mutant minigene produced both Splice Variant 1 and 2 with similar band intensity (42% and 40%, respectively) (Fig. 6) indicating that the c.548-44 T > G alteration results in an imbalance of these 3 transcripts. As it was found in simple heterozygosis, it is difficult to estimate if this contributes to the less penetrant phenotype of the patient.

Figure 6.

RT-PCR results from transfection of wild-type SRD5A2 or c.548-44 T > G SRD5A2 minigenes. A representative agarose gel (n = 3) showing the results of RT-PCR of wild-type (WT) and mutant (MUT) minigene splicing is shown and quantified for the accompanying graph. Schematic diagrams identifying the wild-type transcript (369 bp), a transcript with deletion of 112 nucleotides (257 bp), and a third transcript with exon 4 skipping are shown (217 bp). The panel on the right shows electropherograms of cDNA splicing isoforms generated from wild-type and mutant minigenes. The histogram shows the relative percentage expression of each isoform calculated against total intensity of the bands representing each isoform. Student t test analysis shown; *p < 0.01.

Discussion

Genetic analysis of several genes, including ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), neurofibromin 1 (NF1), von Willebrand factor (VWF) and cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR), has shown that many exonic and intronic alterations, that are classified as neutral/synonymous or missense, have been subsequently found to affect the splicing process25,26.

It is well established that one of the earliest events in eukaryotic exon recognition by the spliceosome machinery is binding of U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) to the 5′ splice site27,28. U1 snRNP binds to the 5′ exon-intron junction of pre-mRNA through base pairing between the single stranded terminal sequence of the U1 RNA molecule and the loosely conserved stretch of nucleotides at the exon-intron boundary (CAG/GURAGU)29. Subsequent to U1 snRNP binding, ordered assembly of the four remaining snRNPs occurs to form the spliceosome, which then undergoes extensive conformational and compositional remodeling to become catalytically active5.

The patient bearing the c.277 + 2 T > G mutation in HSD17B3 was compound heterozygous with the c.277 + 4 A > T and was referred to us at the age of 14 years due to lack of female secondary sexual features and signs of virilization. The patient presented with a 3-cm phallus, perineal urethral opening, and a vaginal introitus and absence of uterus indicated by ultrasound. The gonads were not palpable. The patient also had hirsutism and pubic hair stage 4 with karyotype 46,XY. Molecular findings and minigene experiments confirmed the 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 3 deficiency as the ethiology for 46,XY DSD in this case.

Because c.544 G > A in SRD5A2 is located at the last nucleotide on exon 3, we wanted to identify whether its pathogenic effect could be due to aberrant splicing rather than disruption of SRD5A2 enzymatic activity caused by the missense mutation, p.Gly183Ser, as previously considered21. The patient, homozygous for the mutation c.544 G > A, was referred to us with 22 days of age due to genital ambiguity. The patient’s parents were first cousins and there were no other cases of genital ambiguity in the family. On physical examination the patient had a 1-cm phallus, perineal urethral opening and a vaginal introitus; there was a slight posterior labioscrotal fusion. Both gonads were palpable in the labioscrotal folds. The patient’s karyotype was 46,XY and sex assignment was female. The molecular study confirmed 5-alpha reductase type 2 gene deficiency and analysis of minigene splicing identified that the pathogenicity of this mutation may, at least partly, be the result of aberrant splicing which resulted in exon 3 skipping of SRD5A2.

The results so far described here support the conclusion that c.277 + 2 T > G in HSD17B3 and c.544 G > A in SRD5A2 potentially disrupt binding of U1snRNP to the 5′ splice site therefore inhibiting splicing initiation29,30. These mutations highlight the importance of a conserved 5′ splice site sequence for correct binding of U1 snRNP and spliceosome machinery assembly, and show that disruption of this process may result in human disease30,31.

Exonic and intronic variants may also affect splicing either by creation of new splice sites, activation of existing cryptic splice sites, or disruption/creation of other splicing regulators such as enhancers and silencers32. This was the case for the TP53 c.672 G > A mutation that results in activation of a cryptic 5′ splice site and the expression of an alternative splicing isoform producing a frameshift and activating a premature stop codon33. In this study we have described the c.278delG SRD5A2 mutation, which sees firstly, the activation of a cryptic 5′ splice site, and secondly a frameshift that activates a premature stop codon. The patient was carrying the c.278delG mutation in compound heterozygosis with p.Gly196Ser. This patient was referred to us at the age of 5 years due to genital ambiguity. At physical examination, the patient had a 3-cm phallus, penoscrotal hypospadia, the right gonad was not palpable and the left gonad was palpable in the inguinal channel. The karyotype was 46,XY, therefore the patient was diagnosed with idiopathic 46,XY DSD. As the c.278delG minigene produced a short aberrant splicing isoform compared to WT, and also activated a premature stop codon, we can conclude that the c.278delG mutation may contribute to the observed genital ambiguity and 5alpha-reductase type 2 deficiency in this case.

Although the analysis of intronic sequence variants has been over looked for diagnostic purposes, their importance cannot be neglected as they may also affect the splicing process3. This study highlights the relevance of splicing analysis to verify the pathogenicity of such variants, especially those that are rare. Intronic splicing variants are often located within 50 base pairs of splice sites, but they have also been reported deep within introns where they can be more than 100 base pairs away from exon–intron boundaries34. For example, the deletion of 4 base pairs (GTAA) in intron 20 of ATM, ~3 kb from exon 20 and 0.8 kb from exon 21, leads to the activation of a pseudo exon, producing an aberrant mRNA and consequently the disease phenotype35. In addition, the NF1 deep intronic single nucleotide change, c.31–279 A > G, which results in creation of a 3′ splice site, illustrate how such variants can activate cryptic 5′ splice sites and partial inclusion of a pseudoexon36. Mutations that inactivate or activate alternatively used splice sites could force the expression of one alternative splicing pattern over another, thus potentially favoring the expression of protein isoforms which could be incompatible with a certain cell type, developmental stage, or result in disease37. This was probably the case for the variant c.548–44 T > G, a very rare variant (0.2%, unpublished data) described here in a heterozygous 46,XY DSD patient. The patient was referred to us at the age of 4 years due to unilateral cryptorchidism and the older brother also had cryptorchidism. The patient presented a 4-cm phallus and typical male genitalia; the left gonad was palpable in the inguinal channel and the right gonad in the labioscrotal fold. His karyotype was 46,XY. Because of the heterozygosis of this mutation screening of other genes that could be potentially involved in the phenotype of the patient was performed. Sequencing of exons and intron/exon boundaries of AR, HSD17B3, and NR5A1 genes did not identify any significant sequence variants. Therefore we concluded that the c.548-44 T > G mutation may cause the phenotype by mediating an imbalance of isoform expression which leads directly to genital ambiguity.

Research is still unraveling many of the basic mechanisms that underlie the pre-mRNA splicing process. Clinical cases that identify mutations affecting splicing are useful for highlighting these mechanisms and how they can be disrupted in disease, which is important in diagnostic and therapeutic research. Clinically important mutations that affect the splicing process have been difficult to characterize using current diagnostic algorithms and techniques, particularly in SRD5A2, HSD17B3 and other genes associated with disorders of sex development. Our findings have not only contributed to the phenotypic understanding of these patients but have also highlighted that analysis of sequence variants, not classically affecting protein function, should be assessed for their effect on splicing function to confirm pathogenicity. If RNA is readily available this analysis can be undertaken by RT-PCR, but if not available, as in this study, further confirmation can be achieved by minigene splicing assays. Analysis of splicing mutations is important for both clinical diagnosis and management, and for developing our understanding of underlying pathogenic splicing mechanisms, which will in-turn expand our knowledge of endocrine regulation in sexual differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Minigene construction

Patient or control DNA was used for PCR amplification with oligonucleotides carrying a non-complementary tail for specific restriction enzyme digestion. PCR products were sub-cloned into the pGEM vector (Promega) following manufacturer’s instructions. Sub-cloned PCR fragments and a pCDNA3(+) vector (Invitrogen) containing exons and introns 1–3 of the human alpha globin (HBA1) gene were digested using BamHI, EcoRI and KpnI before ligation38. The sequence of all minigenes were checked by sequencing.

Cell Culture

Human Embryonic Kidney cell lines (HEK-293), were grown in DMEM medium supplemented with 1% streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum, and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Transfection

Minigenes were transfected into HEK-293 cell lines using FuGENE HD (Roche). A mix of 100 μl of DMEM serum-free medium containing 1 ug of vector DNA and 3 μl of FuGENE reagent was incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature before being added to 6 cm-well cell cultures (60% confluent) in the presence of 10% fetal bovine serum.

RNA Extraction and RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from cells 48 hours after transfection using an RNeasy® Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen), following manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA sysntheis was performed on 1 μg total RNA using random primers and Promgea M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega). PCR was performed on resulting cDNA using specific primers to the α-globin gene: forward primer 5′ GGACCCGGTCAACTTCAA 3′; reverse primer 5′ AGCTCTAGCATTTAGGTGACACTAT 3′, with the exception of the c.278delG mutation (SRD5A2 gene) where the forward primer used was: 5′TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG 3′. PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels and band intensity quantified using IMAGEJ. To account for differences in product length, band intensities of each splicing isoform were normalized to the length of the wild-type splice for each minigene. The relative band intensity of each isoform was then calculated as a percentage of the total expression of all isoforms following normalization. Statistical analysis (student’s t test) was performed using GraphPad Prism software.

cDNA Sequencing

Individual PCR fragments were purified using the GeneJET Gel Extraction Kit (Thermo Scientific). Confirmatory sequencing of RT-PCR products was performed with primers used in the PCR reaction. Chromas Lite 2.0 (Technelysium Pty) and CLC Sequence Viewer v.6.8.1 (Qiagen) were used to align and analyse cDNA and amino acid sequences against reference sequences available through the Ensembl database (SRD5A2:ENSG00000277893; HSD17B3: ENSG0000013094839.

In silico analysis

Splicing regulatory sequences in SRD5A2 and HSD17B3 genes were predicted using the computational tools SpliceAid, and Human Splicing Finder version 2.4.140,41.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES)/CAPES “Sandwich” Fellowship: PDSE-0211/13-3 to F.L.Calais. and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq – Brasil) to G.Guerra-Júnior and M.P.Mello. Grant # 2011/24119-1 from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) to M.P. de Mello. HEFCE (NACSLA05) to D. Baralle. Newlife Foundation for disabled children Grant to D. Baralle.

Author Contributions

F.L.C., L.D.S., and M.R. performed experiments and analysed data. F.L.C., L.D.S., M.P.M. and D.B. designed experiments and planned the research. G.G.J. and A.T.M. provided patient samples, and collated and analysed clinical data. F.L.C., L.D.S. and D.B. wrote the manuscript. M.P.M. and D.B. provided critical review and edited the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Flavia Leme de Calais and Lindsay D. Smith contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Berget SM, Moore C, Sharp P. Spliced segments at the 5′ terminus of adenovirus 2 late mRNA. Rev. Med. Virol. 1977;10:356–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black DL. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003;72:291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baralle D, Baralle M. Splicing in action: assessing disease causing sequence changes. J. Med. Genet. 2005;42:737–748. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.029538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z, Burge CB. Splicing regulation: From a parts list of regulatory elements to an integrated splicing code. RNA. 2008;14:802–813. doi: 10.1261/rna.876308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Will, C. L., Lührmann, R. Spliceosome structure and function. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Lewandowska M. A The missing puzzle piece: splicing mutations. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2013;6:2675–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gazzara MR, Vaquero-Garcia J, Lynch KW, Barash Y. In silico to in vivo splicing analysis using splicing code models. Methods. 2014;67:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matera AG, Wang Z. A day in the life of the spliceosome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:108–121. doi: 10.1038/nrm3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busch A, Hertel KJ. Evolution of SR protein and hnRNP splicing regulatory factors. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2012;3:1–12. doi: 10.1002/wrna.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faustino NA, Cooper T. Pre-mRNA splicing and human disease. Genes Dev. 2003;17:419–437. doi: 10.1101/gad.1048803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cartegni L, Chew SL, Krainer AR. Listening to silence and understanding nonsense: exonic mutations that affect splicing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:285–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baralle D, Lucassen A, Buratti E. Missed threads. The impact of pre-mRNA splicing defects on clinical practice. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:810–816. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stenson PD, et al. Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD): 2003 Update. Hum. Mutat. 2003;21:577–581. doi: 10.1002/humu.10212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.López-Bigas N, Audit B, Ouzounis C, Parra G, Guigó R. Are splicing mutations the most frequent cause of hereditary disease? FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1900–1903. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chuang J, et al. Complexities of gender assignment in 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenasetype 3 deficiency: is there a role for early orchiectomy? Int. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2013;1:15. doi: 10.1186/1687-9856-2013-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang H, Imperato-McGinley J, Zhu Y, Rosenwaks Z. 5α-reductase-2 Deficiency’s Effect on Human Fertility. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.11.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen-Kettenis PT. Gender change in 46,XY persons with 5α-reductase-2 deficiency and 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-3 deficiency. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2005;34:399–410. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-4339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Der Zanden, L. F., Van Rooij, I. A., Feitz, W. F., Franke, B., Knoers, N. V., Roeleveld, N. Aetiology of hypospadias: a systematic review of genes and environment. 18, 260–283 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Geissler WM, et al. Male pseudohermaphroditism caused by mutations of testicular 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 3. Nat. Genet. 1994;7:34–39. doi: 10.1038/ng0594-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boehmer AL, et al. 17β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase-3 Deficiency: diagnosis, phenotypic variability, population genetics, and worldwide distribution of ancient and de novo mutations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999;84:4713–4721. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.12.6174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thigpen AE, et al. Molecular Genetics of Steroid 5a-Reductase 2 Deficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;90:799–809. doi: 10.1172/JCI115954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hackel C, et al. New mutations, hotspots, and founder effects in Brazilian patients with steroid 5alpha-reductase deficiency type 2. J. Mol. Med. 2005;83:569–576. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castro CC, et al. Clinical and molecular spectrum of patients with 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 3 (17β-HSD3) deficiency. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol Metabol. 2012;56:533–539. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27302012000800012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veiga-Junior NV, et al. Clinical and Laboratorial features that may differentiate 46,XY DSD due to Partial Androgen Insensitivity and 5α-Reductase Type 2 Deficiency. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2012;2012:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2012/964876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pagani F, Baralle F. Genomic variants in exons and introns: identifying the splicing spoilers. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:389–396. doi: 10.1038/nrg1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yadegari H, et al. Intron retention resulting from a silent mutation in the VWF gene that structurally influences the 5′ splice site. Blood. 2016;128:2144–2152. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-02-699686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mount SM, Pettersson I, Hinterberger M, Karmas A, Steitz JA. The U1 small nuclear RNA-protein complex selectively binds a 5′ splice site in vitro. Cell. 1983;33:509–518. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buratti E, Baralle D. Novel roles of U1 snRNP in alternative splicing Regulation. RNA Biol. 2010;7:412–419. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.4.12153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kondo Y, Oubridge C, Van Roon AM, Nagai K. Crystal structure of human U1 snRNP, a small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle, reveals the mechanism of 5′ splice site recognition. Elife. 2015. 2015;4:e04986. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yelskaya W, et al. CDH1 Missense Variant c.1679C >G (p.T560R) Completely Disrupts Normal Splicing through Creation of a Novel 5′ Splice Site. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brillen A, et al. Succession of splicing regulatory elements determines cryptic 5′ss functionality. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:4202–4216. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Klift HM, et al. Splicing analysis for exonic and intronic mismatch repair gene variants associated with Lynch syndrome confirms high concordance between minigene assays and patient RNA analyses. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2015;3:327–345. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Austin F, Oyarbide U, Massey G, Grimes M, Corey SJ. Synonymous mutation in TP53 results in a cryptic splice site affecting its DNA-binding site in an adolescent with two primary sarcomas. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64:e26584. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaz-Drago, R., Custódio, N., Carmo-Fonseca, M. Deep intronic mutations and human disease. Hum. Genet. 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Pagani F, et al. A new type of mutation causes a splice defect in the ATM. Nature Genet. 2002;30:426–429. doi: 10.1038/ng858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raponi M, et al. Polypyrimidine tract binding protein regulates alternative splicing of an aberrant pseudoexon in NF1. FEBS J. 2008;275:6101–6108. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baralle FE, Giudice J. Alternative splicing as a regulator of development and tissue identity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017;18:437–451. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raponi M, Douglas AGL, Tammaro C, Wilson DI, Baralle D. Evolutionary constraint helps unmask a splicing regulatory region in BRCA1 exon 11. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yates A, et al. Ensembl 2016. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D710–D716. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piva F, Giulietti M, Ballone BA, Principato G. SpliceAid 2: A database of human splicing factors expression data and RNA target motifs. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:81–85. doi: 10.1002/humu.21609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Desmet FO, et al. Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acid Research. 2009;37:e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]