EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The 2015-2017 American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Special Taskforce on Diversifying our Investment in Human Capital was appointed for a two-year term, due to the rigors and complexities of its charges. This report serves as a white paper for academic pharmacy on diversifying our investment in human capital. The Taskforce developed and recommended a representation statement that was adapted and adopted by the AACP House of Delegates at the 2016 AACP Annual Meeting. In addition, the Taskforce developed a diversity statement for the Association that was adopted by the AACP Board of Directors in 2017. The Taskforce also provides recommendations to AACP and to academic pharmacy in this white paper.

Keywords: Diversity, human capital, inclusion, health equity, recruitment

INTRODUCTION AND COMMITTEE CHARGES

The 2013-2014 Argus Commission was charged by 2013-2014 American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) President Peggy Piascik, to respond to the following strategic question: “How can we more effectively address and serve the diversity in our membership at both the institutional and individual levels and prepare our learners to serve an increasingly diverse population of consumers?”1

The Commission assessed the status of academic pharmacy with respect to diversity and inclusion in the broadest sense, and in all elements of the academic mission. Two policy statements were forwarded to the House of Delegates for adoption and seven recommendations were made for a significantly expanded effort in support of our members’ goals in this area.1 In need of a “game changer,” a Special Taskforce on Diversifying Our Investment in Human Capital was appointed for the period of 2015-2017 by 2015-2016 AACP President Cynthia Boyle, to address these recommendations and further assess successful practices of members and colleague organizations.

Previous studies and the work of similar AACP Taskforces provided a base of understanding and offered insight into the unique challenges present in matters of diversity and human capital in academic and professional pharmacy. This Taskforce considered a myriad of available resources and current recommendations within the construct of human capital,2 including the lenses of climate, people, and financial implications, frameworks that impact our investment in the people who make up academic pharmacy – students, faculty, administrators, and staff. The Taskforce was charged to: 1) identify barriers that inhibit the diversification of human capital in colleges and schools of pharmacy; 2) find “game changers” in professional education, healthcare or related areas where substantial improvements have been achieved, and; 3) recommend strategies, vetted through the AACP Councils for input, for short and long-term solutions.3

What has become evident both through the study of existing scholarship and the investigation of this Taskforce is that critical components of the diversification of our investment in human capital will not be served through the examination by committees, nor strategic planning, alone. Member institutions, and indeed AACP itself, must broadly commit to evidence-based, holistic solutions with dedicated institutional, financial, and human resources to support and sustain them.

Following the consideration of the Argus Commission’s analyses regarding underrepresentation, in addition to widely held definitions of underrepresentation in academic health sciences,4,5 the Taskforce agreed that a more contemporary approach to diversity and inclusion is needed and should be used long-term. Rather than defining who is not included in academic pharmacy, the Taskforce believed in taking a more positive position by stating who should be represented. Based on the AACP Core Values,6 and in consideration of the policies previously passed by the AACP House of Delegates, the Taskforce developed and recommended a representation statement that was adapted and adopted by the AACP House of Delegates:

AACP recognizes that a diverse student body, faculty, administration, and staff contribute to improvements in health equity and therefore encourages member institutions to develop faculty, staff, pharmacists and scientists whose background, perspectives, and experiences reflect the diverse communities they serve.7

In addition, the AACP Board of Directors asked the Taskforce to develop and propose a diversity statement to guide the work of the Association. In November 2016, the AACP Board adopted the following:

AACP affirms its commitment to foster an inclusive community and leverage diversity of thought, background, perspective, and experience to advance pharmacy education and improve health.6

This white paper, drawing on a broad body of research and practice, focuses on the implications of investing in our human capital, by identifying the impact of alignment and intentionality with respect to leadership, admissions and recruitment, climate, resources, and metrics to assess effectiveness.

BACKGROUND

Diversity can be leveraged to identify, develop, and advance talent, as well as foster innovations in health equity through education, practice, and research. AACP’s vision of “improve[ing] health for all” will be further enhanced by strategies that involve diversity of thought, opinions, and actions, throughout all levels of its institutions.6

AACP is not alone in emphasizing the advantages of prioritizing diversity and inclusion as a strategic measure. Across healthcare disciplines, professionals and educational organizations recognize that efforts to diversify human capital are fundamental to advancing academic institutions, in training of healthcare professional and scientists, and for the provision of safe and effective patient care. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) supports diversity and inclusion in the governance and teaching at all colleges and schools of pharmacy,8 and together with the Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) affirms that graduates should be capable of providing effective, team-based care for diverse populations.9 The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) published a statement in 2005 that emphasized the importance of workplace diversity and cultural competence in reducing racial and ethnic healthcare disparities.10 The American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) in its 2013 White Paper on Cultural Competence in Health Care and Its Implications for Pharmacy, suggests a model curriculum for providing culturally-sensitive care that also encompasses consideration of disabilities, sexual orientation and gender identity, religion and spirituality, health disparities, and social justice.11

Improvements in health outcomes and narrowing the gap in healthcare disparities represent the most compelling arguments for the development of a diverse composition of human capital in colleges and schools of pharmacy. A diverse and collaborative healthcare workforce enhances the perceived quality of care by facilitating communication and interactions between providers and the populations they serve.12

LEADERSHIP AND INSTITUTIONAL CLIMATE

Leadership in the 21st century demands that health sciences faculty and administrators move beyond diversity alone to capture the potential that comes from inclusion. “If diversity is “the mix,” then inclusion is making the mix work by leveraging the wealth of knowledge, insights, and perspectives in an open, trusting, and diverse educational environment.”13 Diversity, inclusion and climate in academic settings are matters of current discourse and scholarship, however the profession of pharmacy has not capitalized on the opportunity to engage these issues in comparison to other health professions, such as medicine and nursing. Peterson and Spencer defined campus climate in 1990 as the common patterns of important dimensions of organizational life or its member perceptions of and attitudes toward those dimensions.14 Williams defined diversity in 2010 as the very presence of individuals from different backgrounds, with climate as the experience of individuals and groups on a campus — and the quality and extent of the interaction between those various groups and individuals.15 A more modern definition of campus climate is the current attitudes, behaviors, standards and practices of an institution's employees and students and how this impacts success and retention of all community members. A positive, healthy climate, free of negativity and discrimination, offers an environment in which all community members can thrive.16

HUMAN CAPITAL

People make up academic pharmacy: administrators with excellent leadership skills; faculty committed to teaching, scholarship, and service; students dedicated to becoming life-long learners; and staff with the organizational skills to keep the organization moving forward. Ensuring the right people with the right skills, backgrounds, perspectives, and experiences (the “mix”) fill these roles will help colleges and schools of pharmacy not only prepare the next generation of pharmacists and scientists, but will also provide an inclusive environment to develop a diverse healthcare workforce. This diverse workforce whose backgrounds, perspectives, and experiences reflect the diverse communities they serve will lead to improvements in health equity.17

Recruitment and Student Admissions

There are many efforts that must work cohesively in order to diversify the pharmacy workforce, including health profession advising and selection during the admissions process, which are critical factors in bringing individuals from varied backgrounds into the profession. Data available to admissions committees have a direct impact on selection. The methodology used to collect data, and how that data is utilized by the admission committee (eg, weighing lived experiences, vs. relying solely on standardized test scores) also have a direct impact on selection.18-21 The Pharmacy College Application Service (PharmCAS), the centralized application service for pharmacy schools, is used by the majority of pharmacy schools (126 of 139). Given the large percentage of participation by colleges and schools of pharmacy, the data collected by PharmCAS plays a significant role in the selection process of future student pharmacists. PharmCAS receives all of the desired applicant information in an electronic format, including colleges attended, prior coursework, biographical information, admission test scores, personal information, honors and scholarships, a personal essay, publications, and extracurricular and work activities. Applicants enter this information and then select one or more pharmacy programs to which they would like to apply. Further, faculty and health professions advisors’ knowledge and/or perception of pharmacy admission processes form the foundation of the guidance provided to prospective students. Applicants may opt out of the process if the information they receive makes the goal appear to be unattainable.22

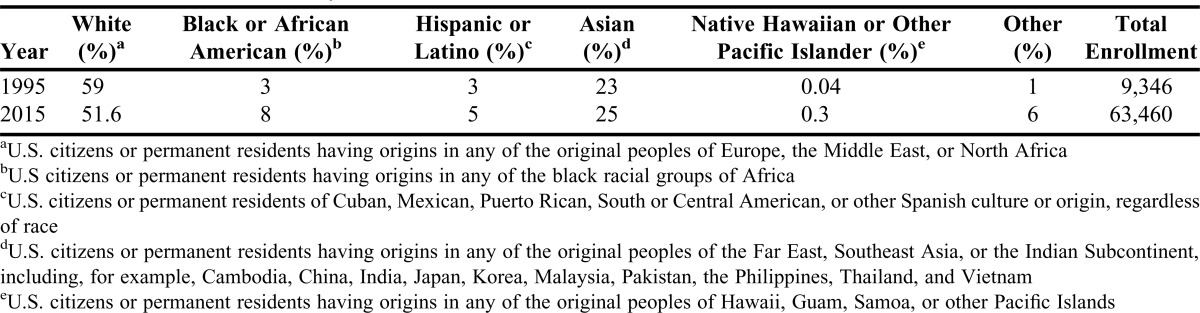

AACP’s statistics indicate that despite monumental growth in ACPE-accredited Doctor of Pharmacy programs, the shift in the demographic profile has been small by comparison between 1995 and 2015 (Table 1).23,24 As a result, it can be surmised that the change in the demographic profile may be attributed to the proliferation of programs in diverse geographic regions rather than the result of a proactive diversity and inclusion plan of action.

Table 1.

Programs created to prepare underrepresented minority students for the rigor of Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) and health professional programs have yielded some success.25,26 The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Interprofessional Health Post-Baccalaureate Certificate Program, a year-long program designed for those needing a stronger academic foundation than their current undergraduate coursework has provided, is recommended for applicants who have previously been unsuccessful in gaining admission to a college or school of pharmacy. The program targets students from disadvantaged backgrounds, underserved communities, and those individuals whose backgrounds are traditionally underrepresented in the pharmacy profession. The program uses a combination of upper-division academic coursework, personalized support with monitored progress by UCSF School of Pharmacy staff and faculty. Additionally, the program offers Pharmacy College Admissions Test (PCAT) preparation, workshops on academic and professional development, and seminars on various health and career-related topics.27 Another example in a related health profession is The University of Michigan post-baccalaureate program targeting individuals who either did not gain admission to medical school, are interested in changing their careers, are economically disadvantaged, or are underrepresented in medicine. The year-long curriculum includes basic science courses, research experience, academic counseling, reading and study skills development, and mentoring. A component of the program also includes support in applying for admission and financial aid. The program reports that 80% of participants entered medical school.28,29 The University of Maryland, Baltimore County, developed the Meyerhoff Scholars Program for undergraduates, integrating thirteen key components: recruitment, financial aid, summer bridge, program values, study groups, community, advising/counseling, tutoring, research internships, mentors, faculty involvement, administrative involvement, and family involvement to increase the number of minority students succeeding in STEM fields.30 Additionally, the Morgan State University promotes collaborative degree programs between historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and other state universities to prevent inequities that perpetuate segregation and potentially disadvantage minorities.31

Further, the definition of diversity is trending beyond simple demographics.32 Increasingly, researchers say it is more about building cultural dexterity, achieving outcomes, and enhanced opportunities for innovation. Clearly defined metrics render the accountability and focus needed to optimize impact and return on investment and further continuous improvement of diversity-related initiatives. The progress of these trends is hampered by barriers in recruitment and retention of underrepresented groups, gaps in access to resources, and institutional climate issues impacting the ability to perform.

Recruitment and Retention of the Faculty Workforce

It is necessary to be realistic in our efforts to diversify the academic pharmacy workforce. Although goodwill and commitment to participate are required, they are not enough to guarantee that people will implement diversity initiatives if time and resources are not allocated. Successful programs have assigned full-time personnel to be in charge of leading the vision, conducting strategic planning and assessment, as well as defining initiatives and ensuring diversity efforts are not diluted.

Both recruitment and retention programs are important components of cultivating diverse faculty and staff. A systematic review from our colleagues in medicine showed that in order for schools to be successful in diversifying their faculty, intentional programs for recruitment and retention must be in place.33 A study of two health science schools suggested that programs for women and underrepresented minorities must be vigilant and address the needs of the individual faculty members.34 Other perceived barriers include promotion and tenure advancement criteria that are not applied in a consistent and equitable manner. The literature indicates that a primary source of minority workforce dissatisfaction and attrition is the lack of strong mentoring and professional development programs at the institution.35

INFRASTRUCTURE AND RESOURCE COMMITMENT

Strategic planning alone does not guarantee results of diversity initiatives. Commitment at all organizational levels is required to execute the move from rhetoric and plans to reality. It is, likewise, not sufficient to appoint a Diversity Officer or Chief to independently execute these plans. Functional, comprehensive diversity initiatives require a dedicated and defined infrastructure to build and sustain them. High-impact initiatives require members of the university community and others, such as facilitators, consultants and peer advisors, as well as financial, facility, and time allocations.

Student Financial Aid

Financial barriers that are identified for underrepresented students pursuing careers in health sciences include costs associated with applying to programs, tuition, understanding of how financial aid and scholarships are obtained, and obligations to support family.35 Students considering pursuing medicine or dentistry identified the costs of preparation courses for entrance exams, travel for interviews while applying for admission and during the residency match process as concerns. The rigor of the prerequisite requirements may limit the amount of time available to work, leaving students with fewer financial resources.36 A review of studies examining underrepresented nursing student barriers identified several challenges. The first was that underrepresented students are more likely to work outside of school. This outside work may interfere with academic success resulting in prolonging the length of time needed to complete their degrees.37 Additionally, the cost of four year programs results in some students choosing two year community colleges which may not provide all the prerequisite coursework that is required for professional education resulting in extending the time and cost to complete the program.38 Underrepresented students are more likely to be unfamiliar with accessing financial aid or pursuing scholarships.37 There is a declining trend in need-based aid towards merit-based aid.39 This shift may result in less access for underrepresented students. Pell Grant funding has significantly increased from 2008-2016 providing more students access to Pell Grants; however, the current administration has proposed potential cuts to the Pell Grant program, which may further negatively impact access for underrepresented students.40 High achieving low income students are less likely to apply for admission at selective institutions due to concerns of affordability and a lack of accurate guidance. This results in high achieving, low income students under-matching and selecting schools where the student body average academic capacity is lower.41 Appendix I outlines “game changers” in the area of diversity and inclusion identified by the Taskforce, and includes potential solutions to financial barriers for students.

Faculty Equitable Compensation and Benefits Packages

While there are legitimate reasons for the wide range of compensation packages between individual faculty members at colleges and schools of pharmacy, such as the focus of research, scholarly activities, and clinical practice of the individual, studies have shown that salaries for female faculty and those belonging to underrepresented populations are paid at lower levels than their male and white counterparts.42 Colleges and schools of pharmacy face challenges of providing adequate start-up packages for research faculty or faculty in general. Additionally, the economic challenges (increased housing costs, cost of living, decreased retirement benefits, costs of quality and conveniently located childcare services, increasing healthcare costs that include dental and vision) and the overall perception of a lack of job security, is a challenge in recruiting not only faculty from underrepresented groups, but all faculty.43

Scholarship

Ironically, due to the variety of disciplines represented within colleges and schools of pharmacy, faculty may not find the academic environment supportive of academic and scholarly activities related to diversity and inclusion. The climate of a particular institution may also marginalize the research and scholarly efforts of faculty who seek out what are considered nontraditional areas of research. Such attitudes may implicitly discourage such activities, particularly when these are not considered areas of research or academic work that are valued in the promotion process.44 Encouragement of scholarship on the topics of diversity and inclusion, as well as emphasis on the value of such scholarship as an institutional and professional priority in pharmacy, is essential.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Taskforce collected promising practices in the areas discussed in this white paper, but received only one response, so the Taskforce conducted a thorough literature review to identify promising practices and “game changers”. The Taskforce defines “game changers” as intentional institutional actions, commitments, or initiatives undertaken to address issues relating to diversification of our investment in human capital that are continuously assessed to yield measurable efficacy and impact. Appendix I outlines “game changers” in the area of diversity and inclusion identified by the Taskforce. In addition, the Taskforce had recommendations intended to further the Association’s work toward diversifying our investment in human capital.

Recommendation 1, 2, & 3

In order for AACP to achieve the goals in its strategic plan related to diversity45 and to begin to work within the new AACP Diversity Statement guiding the work of the Association, the Taskforce recommends:

1. AACP increase staffing in the area of diversity and inclusion. (The Taskforce is pleased to see that at time of publication, AACP has created a new staff position devoted to diversity and recruitment.)

2. AACP implement a culture and climate survey across all schools that may be added to the yearly AACP surveys.

3. AACP consider diversity and inclusion topics for future Association meetings and committee work.

Recommendation 4

AACP’s Strategic Plan Goal 1.3 of Priority 1, Enriching the Applicant Pipeline, is to appropriately measure and increase diversity (broadly defined) in the applicant pipeline, calling for collection of appropriate information about applicant backgrounds to better assess and define diversity of the applicant pool.45 Colleges and schools of pharmacy have been charged to recruit and admit students with backgrounds, perspectives, and experiences that reflect the diverse communities they serve and so desire to have information that allows for a more complete picture of the diverse characteristics of the applicant.7 In order for the Association to accomplish these goals, the Taskforce recommends:

• AACP study the data collection process used in the AACP Application Services (PharmCAS, PharmGrad, PharmDirect) to improve the information collected allowing for more holistic reviews of applicants.

CONCLUSION

AACP and its member institutions must engage in rigorous scholarly examination and intentional programmatic initiatives to correct course if we are truly committed to investing in diversifying human capital beyond demographics. As previously mentioned, the breadth and depth of scholarship in this area for pharmacy and pharmaceutical sciences is scant, therefore we must include complementary fields to examine game-changing best practices. To truly achieve the goal of advancing health equity, academic pharmacy must be purposeful in its efforts and investments toward diversifying the people who make up academic pharmacy.

Appendix 1. GAME CHANGER – MEYERHOFF SCHOLARS PROGRAM

Institution: University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Contact Person (at time of publication): Keith Harmon

Program Profile: The Meyerhoff Scholars program is open to prospective undergraduates of all backgrounds who plan to pursue doctoral study in the sciences or engineering, and who are interested in the advancement of underrepresented minorities (URM) in those fields. Instituted in 1988 with a gift from Robert and Jane Meyerhoff, the first cohort enrolled in 1989. There are now 1,000 Meyerhoff alumni out working in STEM and health.

Program Outcomes:

Since 1993, the program has graduated over 1,000 students. As of April 2016, the program has achieved the following results:

• Alumni from the program have earned 231 PhDs, which includes 45 MD/PhDs, 1 DDS/PhD and 1 DVM/PhD. Graduates have also earned 107 M.D. degrees, as well as 247 Master’s degrees, primarily in engineering, and computer science and related areas. Meyerhoff graduates have received these degrees from such institutions as Harvard, Stanford, Duke, M.I.T., Berkeley, University of Michigan, Yale, Georgia Tech, Johns Hopkins, Carnegie Mellon, Rice, University of Pittsburgh, NYU, and the University of Maryland.

• Over 300 alumni are currently enrolled in graduate and professional degree programs.

• An additional 270 students are currently enrolled in the program for the 2016-2017 academic year, of whom 57% are African American, 15% Caucasian, 15% Asian, 12% Hispanic, 1% Native American.

• The program is having a dramatically positive impact on the number of minority students succeeding in STEM fields; students were 5.3 times more likely to have graduated from or be currently attending a STEM PhD or MD/PhD program than those students who were invited to join the program but declined and attended another university.

Change, past 5-10 years: In 1996, the Meyerhoff Graduate Fellows Program was instituted, focusing on promoting cultural diversity in the biomedical sciences at the graduate level. It began with an MBRS-IMSD (Minority Biomedical Research Support – Initiative for Maximizing Student Diversity) grant from the National Institute of General Medical Science. The goal of the program is to increase diversity among students pursuing PhD degrees in the biomedical and behavioral sciences.

Program Strategies:

13 Key Components of the Meyerhoff Program

1. Recruitment – The Meyerhoff Scholars Program currently receives approximately 2,000 nominations and enrolls approximately 50 new students each year. The top 100-150 applicants and their families are invited to attend an on-campus selection weekend where faculty, administration, program staff, and current Meyerhoff Scholars meet with the applicants in both formal and informal circumstances. This in-depth screening process helps identify students who are a good fit for UMBC, students who are not only academically prepared for a science, engineering, or math major, but also are genuinely committed to a postgraduate research-based degree and career.

2. Financial Aid – Meyerhoff Scholars receive a comprehensive, four-year financial-aid package, including tuition, and room and board; Meyerhoff finalists receive more limited support. Continued support is contingent upon maintaining a B average in a science or engineering major.

3. Summer Bridge – Once selected for the program, each cohort of incoming Meyerhoff Scholars attends a mandatory pre-freshman six-week Summer Bridge Program, during which they take courses in math, science, and the humanities. They also learn time management, problem-solving, and study skills and take part in social and cultural events. Summer Bridge prepares scholars for the new expectations and requirements of college courses, and helps develop a close-knit peer group.

4. Program Values – Beginning at the recruitment phase, the Meyerhoff Scholars Program emphasizes the goal of achieving a research-based PhD. Other values consistently emphasized include striving for outstanding academic achievement, seeking help (tutoring, advising) from a variety of sources, and supporting one’s peers. Scholars are also expected to participate in community service projects.

5. Study Groups – Studying in groups is strongly and consistently encouraged by program staff, as it is viewed as an important part of succeeding in a science, math, or engineering major. Meyerhoff Scholars consistently rank study groups as one of the most positive, beneficial aspects of the program.

6. Program Community – The Meyerhoff Scholars Program provides a family-like, campus-based social and academic support system for students. Students live in the same residence hall during their first year and are required to live on campus during subsequent years. Staff regularly hold group meetings called family meetings with students.

7. Personal Advising and Counseling – A full-time academic advisor, along with the programs executive director, director, and assistant director, regularly monitors and advises students. Counselors are not only concerned with academic planning and performance, but also with any personal problems students may have.

8. Tutoring – All Meyerhoff Scholars are encouraged to take advantage of departmental and university tutoring resources to maximize academic achievement students are expected to excel, and are encouraged to seek not just A’s, but high A’s. Many Meyerhoff Scholars serve as peer tutors, working with both Meyerhoff and non-Meyerhoff students.

9. Summer Research Internships – All Meyerhoff Scholars are exposed to research early on in order to gain hands-on experience and to develop a clearer understanding of what studying science entails. Program staff use an extensive network of contacts to arrange summer science and engineering internships, opportunities that maintain intrinsic interest in science, math, or engineering careers and create mentoring relationships.

10. Mentors – Each scholar is paired with a mentor, recruited from among Baltimore- and Washington-area professionals in science, engineering, and health. In addition, scholars have faculty mentors in research labs both on and off campus, across the nation, and in other countries.

11. Faculty Involvement – Department chairs and faculty are involved in all aspects of the program, including recruitment, teaching, mentoring research, and special events and activities. Faculty involvement promotes an environment with ready access to academic help and encouragement, fosters inter-personal relationships, and raises faculty expectations for minority student’s academic performance.

12. Administrative Involvement and Public Support – The Meyerhoff Scholars Program is supported at all levels of the university, one factor researchers have cited as important for the success of any intervention program. Funding partners to date include the National Science Foundation, NASA, IBM, AT&T, and the Sloan, Lilly, and Abel foundations.

13. Family Involvement – Parents are kept informed of their child’s progress, are invited to special counseling sessions if problems emerge, and are included in various special events. The parents have formed the Meyerhoff Parents Association, which serves as a fundraising and mutual support resource.

Assessment and Evaluation:

• Alumni of the program are tracked to see which colleges they attend, which degree programs they enroll in and the likelihood the alumni will enroll, graduate from, and work in a STEM field.

• Feedback from scholars, mentors, and faculty.

• Each component of the program involves a rigorous, in-depth selection process that evaluates the student’s commitment to community service and a postgraduate research-based degree and career.

GAME CHANGER – UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO/NEW MEXICO STATE UNIVERSITY COOPERATIVE PHARMACY PROGRAM

Institution: University of New Mexico College of Pharmacy

Contact Person (at time of publication): Donald A. Godwin

Program Profile: Underrepresented high school students in southern New Mexico who are interested in pharmacy school. Ten students are selected annually for the program. Selected students complete their three years of pharmacy pre-requisites at New Mexico State University (NMSU) and then transfer to the University of New Mexico (UNM) for their PharmD studies. Students are required to complete their IPPEs (summers after P1 and P2 years) in or near their hometowns as well as a majority of their APPEs. Students are introduced to the southern New Mexico pharmacy community during their undergraduate years through seminars, community service, and job shadowing and maintain those connections during their pharmacy training through experiential education.

Program Outcomes:

• Increase the number of pharmacy students from southern New Mexico enrolled in College of Pharmacy

• Increase diversity of the pharmacy profession in southern New Mexico by increasing the number of pharmacists who are sensitive to the unique needs of a significant Hispanic population

• Enhance accessibility of pharmacy education for the people of southern New Mexico

• Serve the pharmaceutical care needs of the underserved in the southern New Mexico region

Change, past 5-10 years: Overall, the co-op program is very well established now and has increased awareness of the pharmacy profession in southern New Mexico. The presence of UNM COP faculty at NMSU has also increased awareness of pharmacy among college students resulting in a higher number of students accepted from that school. With only 2 graduating classes so far, it is too early to determine if the program will lead to enhanced care for the underserved of southern New Mexico or will increase the overall diversity of the pharmacy profession. The program has, however, made great progress in increasing the number of pharmacy students from southern New Mexico and increased the accessibility of pharmacy education to the people of that region.

Program Strategies:

• Secure support from New Mexico pharmacy professional organizations and New Mexico Board of Pharmacy for the program as well as a partner school (NMSU).

• Secure funding from the New Mexico Legislature for faculty lines, administrative support, operating costs, and student scholarships.

• Complete Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with New Mexico State University to include office space for UNM faculty at NMSU.

• Create articulation agreement with NMSU to allow Cooperative Pharmacy Program students to earn a baccalaureate degree from NMSU following the students’ second year of pharmacy school.

Assessment and Evaluation:

-

• Number of pharmacy students from southern New Mexico

-

○ Increase from 67 southern students in 2010 to 83 in 2016 in a time of overall declining enrollment

▪ A 24% increase in students from southern New Mexico with a 6% decrease in overall enrollment

-

-

• Racial/ethnic diversity of cooperative pharmacy students

○ American Indian 4%, Black 2%, Asian 6%, Hispanic 51%, White 37%

-

• 4-year graduation rate

○ Co-op students have a 100% 4-year graduation rate vs. 92% for all PharmD students

-

• Percentage of co-op graduates working in southern New Mexico or rural/underserved areas in other states

-

○ 64% success

▪ 50% of graduates practicing in southern New Mexico

▪ 14% of graduates practicing in other states

-

GAME CHANGER – THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL ESHELMAN SCHOOL OF PHARMACY OFFICE OF INNOVATIVE LEADERSHIP & DIVERSITY

Institution: The University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill Eshelman School of Pharmacy

Contact Person (at time of publication): Carla White

Program Profile: The UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy strives to be a diverse community of people, and has the core value that a diversity of views, genders, races, ethnic backgrounds, and experiences of its faculty, staff and students is vital to allow the school to execute its mission to develop leaders who have a positive impact on human health worldwide. A primary mission of the Office of Innovative Leadership and Diversity (OILD) at the School is to recruit, retain, and develop the next generation of pharmacy leaders. We envision a school that reflects, in all its dimensions, the population it serves.

Program Outcomes:

• Annually, approximately 600 prospective students engage with OILD. An average of 320 prospective students participate in OILD Program Initiatives: Leadership Excellence and Development (LEAD) Program – college program 80 students and high school program 80 students; Mentoring Future Leaders in Pharmacy (M-FLIP) – 60 college students; Leadership Academy – 30 college and 30 high school students, and Undergraduates for Diversity in Pharmacy (USDP) – 40 college students.

• Ninety percent of Doctor of Pharmacy Program Students who had a high level of engagement with OILD and applied were admitted, producing a yield of 47% of the student body (classes of 2017-2020).

• Sixty percent of the PharmD program’s underrepresented talent attended one or more programs and received mentoring and guidance through the Office prior to admission.

• Twenty percent of prospective students participating OILD program initiatives were first generation college students, 2016-2017.

• Historically underrepresented students in the professional program (African American/Black, Hispanic/Latino, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander) reflected 15%, 8% 20% , and 12% for the of the Class of 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020, respectively.

• Approximately one half of the states within the US are represented in the PharmD Program (Classes 2017-2020).

• All graduate students (112) were required to attend the Cross Cultural Leadership Workshops (2015-2017), and 141 professional students completed the Cross Cultural Interactions Module within the new curriculum.

• Approximately, 250-300 students faculty and staff attend each International Hour,

• Health Communication Courses - the undergraduate course doubled in enrollment from 30 to 60 seats to meet demand, and currently the communication elective for professional and graduate students is of high interest and the fills close to capacity.

• OILD contributed to 29 publications and 72 presentations and is regarded as a leading, award-winning entity in advancing diversity and inclusion in the health sciences.

Data accessed 4-18-2017 School Website, Quickfacts, Fast Fasts, OILD

Change, past 5-10 years: Increased inclusion: high levels of student, faculty and staff cross cultural engagement and preparation; and expanded global education, research, and practice opportunities through the Office of Global Engagement have maximized potential to advance diversity and inclusion at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy. The most notable shift is the development of a pharmacy workforce similar to University, State, and US demographics in the PharmD program.

Program Strategies:

A purposeful multilayered and multifaceted approach aimed at the development of a sustainable infrastructure that was conceptualized and implemented by the Office of Innovative Leadership and Diversity. Office functionality spans across the School and intersects with multiple units.

Prospective Students

• Recruitment Ambassadors Program (RAP) 2008 – to executive an aggressive outreach effort, and Pre-Pharmacy Club 2009 – increase campus exposure for undergraduates and opportunities to learn through faculty and student engagement. These initiatives are managed by the Office of Student and Curricular Affairs.

• LEAD Program 2009 – an application is required based on leadership potential, intellectual vitality, community engagement, and academic performance. LEAD is designed to cultivate leadership abilities of participants by offering a one day experience to discover and network with trailblazers of the profession. Following LEAD, program participants receive invitations to Leadership Academy 2011- a leadership development program held over a four month period, consisting of seminars, specialized projects, and networking opportunities, and M-FLIP 2011– provides an individualized and highly structured mentorship between Student Pharmacists and prospective college students. These connections foster building professional relationships, and increasing access to knowledge and confidence for those pursuing a career in pharmacy.

• USDP 2013 – encourages and supports underrepresented college students seeking careers in pharmacy and the pharmaceutical sciences. Students receive support in attaining their academic, social, and professional goals.

• Contemporary Communications in Healthcare 2013 – undergraduate course to expose learners to approaches and strategies that optimize diverse communications in healthcare.

Professional Students

• Contemporary and Applied Communications in Healthcare 2015 – course elective for professional and graduate students designed to develop health communication skills across a broad range of constituents and key stakeholders.

• Cultural Competence Communication Module 2016 – principals, ethics, and skills necessary to be responsive and work effectively across cultures.

• OILD Leadership Opportunities Ongoing – Twenty seven leadership opportunities are reserved for admitted students that participated in LEAD, M’FLIP, and Leadership Academy. They serve in various roles centered around program refinement and facilitation.

Graduate Students

• Cross Cultural Leadership Development Workshops 2015 – facilitated by Pharmaceutical Science PhD Candidates. These workshops provide strategies on how to become a better leaders by encouraging the understanding of various cultural perspectives, providing an opportunity for self-reflection, and developing skills to implement in their professional career. The workshops are held during the pharmacy graduate program’s required division seminars. These efforts are being further developed by graduate students with faculty guidance.

Postdoctoral Students

• Postdoctoral Education Fellowship 2011 – the primary focus is diversity and inclusion scholarship, ranging from institutional effectiveness to program and student- centered assessment.

School Climate

• International Hour 2015 – established with School of Pharmacy Staff to celebrate the School’s rich cultures through music and food tastings.

• Inclusive Engagement Seminar Series 2016 – implemented in collaboration with Carolina Association of Pharmacy Students and the School of Pharmacy HR Dept. Both initiatives are spaces for faculty, students and staff to engage, learn, and increase opportunities for collaboration.

Assessment and Evaluation: Compositional, engagement, and performance metrics are utilized to assess program initiatives.

GAME CHANGER – THE URBAN PIPELINE PROGRAM (UPP) SUMMER HIGH SCHOOL PHARMACY ENRICHMENT PROGRAM

Name of Institution: The University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) College of Pharmacy (COP)

Contact Person (at time of publication): Clara Okorie-Awé

Program Profile: The UPP Summer High School Pharmacy Enrichment Program targets Chicago Public School (CPS) and South Suburban students who are juniors. Approximately 35 to 40 students are selected to participate after been vetted by teachers and subjected to interviews by UIC-COP faculty and students, and the Chicago Public School’s Department of College and Career Preparation staff. Duration: 8 weeks of comprehensive, academic, experiential, mentoring, hands-on activities with faculty preceptors, and professional, and social development seminars. Students participate in a 6-week experiential/pharmacy technician/shadowing at CVS and Walgreens.

Program Outcomes:

• From 2005 to 2016, 92% UPP participants responded that they were influenced/motivated to pursue pharmacy as a career.46

• Currently, thirteen UPP participants are enrolled at UIC-COP and other pharmacy schools. So far, eight have graduated from UIC-COP with an additional twelve in the pipeline to graduate.

• Appreciable increase in the number of underrepresented student body diversity from 9% to 15%.

Change past 5-10 years:

• Increase in the number of underrepresented student body diversity from 9% to 15%.

• Diversity and inclusion now leveraged as one of the hallmarks of the college.

• Teaching and learning takes into account all aspects of cultural competency.

• College commitment to diversity and inclusion; dean as diversity champion.

Program Strategies:

• Faculty commitment and buy-in of the program goal. Shared responsibilities in the College’s diversity and inclusion outcomes, and success of the program.

• More pipeline partnerships with CPS and charter schools in the Chicagoland area.

• Building of strong community relations partnerships and alliances with neighborhoods about UIC-COP health initiatives to benefit the communities.

• Linking the goals of the program to the health needs of the great city of Chicago in bridging health disparities.

Assessment and Evaluation:

• Participants are tracked longitudinally through high school, college, and matriculation into UIC-COP or pharmacy schools.

• Student focus group

• Surveys (pre-, mid- and post)

• UIC-COP staff act as secondary pre-pharmacy advisor to UPP students at UIC or other institutions ensuring that they are taking required courses and on track with their pre-pharmacy curriculum.

GAME CHANGER – CENTER OF EXCELLENCE (XUCOP/COE)

Institution: Xavier University of Louisiana (XULA) College of Pharmacy

Contact Person (at time of publication): Kathleen B. Kennedy

Program Profile: XULA is one of four designated Historically Black College and Universities (HBCUs) with a Centers of Excellence (COE) Program. The focus of this COE program is on the recruitment, training and retention of African American faculty and students identified as underrepresented minorities in the pharmacy profession.

Program Outcomes:

• During 2013-2015 a total of 122 African American high school students participated in the COE Student Enrichment Program. From the total of graduating seniors during this period, as of fall 2015, twenty-six (21.3%) have enrolled at Xavier University majoring in the sciences with twenty of them (77%) declaring a Pre-Pharmacy major.

• Percentages of African American high school students admitted to the CAP and consequently enrolled in XUCOP have been consistent: 72% in 2013, 71% in 2015 and 50% in 2016.

• The university was recently ranked #6 in the entire country for social mobility and student transformation and was one of only two private institutions in the top 10.47

Change past 5-10 years:

• During the last decade XULA has been among the nation's top four colleges of pharmacy in graduating African Americans with Doctor of Pharmacy degrees.48

• The Academic Enrichment Program (AEP) started in 2009 with the primary objective of identifying students early who are at-risk of academic failure and to assist them by providing AEP intervention services. AEP services include: individual or group tutoring, Comprehensive Study Schedule (CSS) development, student counseling/referral service, seminars on test-taking strategies, and faculty/tutor facilitated examination reviews. The percentage of African American AEP enrollees increased from 42% in fall 2014 to 53% in fall 2016. As result of this program, the percentage of first-year African American students who earned one or more failing grades during the first semester has decreased from 31% in 2012 to 9% in 2016.

• XULA is one of ten colleges and universities to receive a Building Infrastructure Leading to Diversity (BUILD) award. These awards are part of a larger initiative by the NIH, committed to enhancing the diversity of the NIH-funded workforce.

Program Strategies:

The XUCOP/COE program addresses main issues affecting the development of a competitive pipeline of African Americans in the pharmacy profession. Primary components of the XULA/COE program related to recruitment and retention of African American pharmacy students along the pipeline are:

-

• For High School Students:

○ The “START” Program introduces selected high school students to fundamental concepts in mathematics (MathStar), science (BioStar and ChemStar), and analytical reasoning (SOAR) that provide a framework for high school courses in these areas.

○ The COE Student Enrichment Program was established to develop a pipeline of quality local high school students who are academically prepared for the rigors of college. Year-round program activities providing pre-induction experiences to pharmacy and health profession careers.

○ The Contingent Admit Program (CAP) was developed to identify and attract high-performing high school seniors to XULA College of Pharmacy (XUCOP) upon graduation from high school. Those who qualify and are accepted into the CAP will be guaranteed a seat in the professional pharmacy program if they satisfactorily complete all of their pre-requisite courses in two years and an on-site interview.

-

• For Pre-Pharmacy Students:

○ The Chemistry/Pre-Pharmacy Summer Program (CPPSP) which has two objectives: 1) Students work with Xavier faculty in order to prepare them for the academic challenges they will face in their first year of the pre-pharmacy program, and 2) Participants are inculcated to the pharmacy profession through seminars and meetings with pharmacy professionals.

-

• For Pharmacy Students:

○ The Pharmacy Pre-Matriculation Summer Program (PPMSP) was implemented to expose incoming first-year pharmacy students to the rigors of the first semester course work while introducing them to the XUCOP professional school culture. The content presented during the PPMSP provides students with a preview of first semester courses and aids them in developing strategies to understand and study course material.

-

• For Post-graduate Students

○ The Research Scholars Program was developed to encourage qualified African American pharmacy students to pursue post-graduate studies. Students are actively engaged in research, participate in seminars and workshops, present their research at national meetings, and prepare for interviews for residency programs.

Assessment and Evaluation:

The XUCOP Office of Student Affairs (OSA) organizes and oversees all activities and programs to boost student engagement through a system of monitoring and mentoring for the academic progress of all students. The XUCOP Director of Assessment is tasked with monitoring and evaluation of program outcomes.

GAME CHANGER – FOCUSED DIVERSITY RECRUITING EFFORTS INCLUDING DIRECT ADMIT PROGRAM

Institution Name: University of the Incarnate Word Feik School of Pharmacy

Contact Person (at time of publication): Amy Diepenbrock

Program Profile: As a Hispanic serving institution in South Texas, UIW Feik School of Pharmacy has brought in a diverse pool of applicants from the region, and has tailored recruiting efforts over the years to focus on South Texas, yielding an average of 20-30 program participants. As part of this effort, the Direct Admit program was created, offering extra incentives to Texas public high school students in the Top 5% of their graduating class.

Program Outcomes: Since 2012, approximately 100 students have come through this program thereby enhancing the diversity of this program and meeting the University’s mission to service South Texas.

Change past 5-10 years: Since inception, the program has helped to cultivate a diverse pool of pre-pharmacy students seeking to serve South Texas after matriculating and completing the PharmD program.

Throughout the 11-year history of the pharmacy program the profile has remained consistent. The balanced profile of ethnicities, having young and older students, a large number of first generation college graduates, and the male to female ratio shows little fluctuation from year to year.

Program Strategies:

• Extensive recruitment into population areas with innovative high school programs that had been overlooked by larger institutions.

• The Dean created the Office of Student Affairs as the first building block of the program. Part of the charge given to that office was to embrace diversity, learning as much as possible about cultural competency and sensitivity. It is this office that has helped set the tone for cultural awareness throughout the school.

• A Pre-Pharmacy program that has structure both academically and socially. A dedicated advisor for the pre-pharmacy students makes their transition from high school to college and then into pharmacy (or out of pharmacy) much smoother.

• To continue the tide of acquiring the brightest students from all walks of life, in 2014, the school adopted a ‘Direct Admit.’ For these students the PCAT is waived in order to solidify the process for acceptance; there are additional requirements to participate actively in the Pre-Pharmacy Association; significant scholarship dependent on GPA.

Assessment and Evaluation:

• The success of the pharmacy school Direct Admit spurred the expansion of the program to the main campus of the University for all majors.

• One of the most telling parameters by which success is measured is the consistent profile of pharmacy students. Each year, the numbers remain about the same.

• Assessment and evaluation is ongoing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yanchick VA, Baldwin JN, Bootman JL, Carter RA, Crabtree BL, Maine LL. Report of the 2013-2014 Argus Commission: Diversity and Inclusion in Pharmacy Education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(10):Article S21. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7810S21. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7810S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aviant Group. What is Human Capital. http://aviantgroup.com/humancapital.asp. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- 3.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Special Task Force on Diversifying Our Investment in Human Capital. http://www.aacp.org/governance/COMMITTEES/Special_Committees_ and_Task_Forces/Special_Task _Force_on_Diversifying_Our_Investment_in_Human_Capital/Pages/default.aspx. Updated March 13, 2016. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- 4.Association of American Medical Colleges. Definition of Underrepresented in Medicine. https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/urm/. Accessed November 10, 2015.

- 5.American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine. Definition of Underrepresented Minorities. https://www.aacom.org/become-a-doctor/diversity/diversity-data/applicants. Accessed November 10, 2015.

- 6.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Mission, Vision, Values. http://www.aacp.org/about/Pages/AACPMissionandVision.aspx. Updated February 27, 2017. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- 7.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. House of Delegates Cumulative Policies 1980-2016. http://www.aacp.org/governance/HOD/Documents/Cumulative%20Policy%201980-2016.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2015.

- 8.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Key Elements for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree: Standards 2016. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Released February 2, 2015. Accessed November 10, 2015.

- 9.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, Robinson ET, DeLander G, Beck DE, et al. Center for Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 Educational Outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):Article 162. doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162. doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanderpool HK. Report of the ASHP Ad Hoc Committee on Ethnic Diversity and Cultural Competence. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2005;62:1924–1930. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez M, Poirier T, Karaoui LR, Echeverri M, Chen AM, Lee SY, Vyas D, O’Neil CK, Jackson AN. (2013). Cultural Competency in Health Care and Its Implications for Pharmacy, Part 3A: Emphasis on Pharmacy Education Curriculums and Future Directions. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(12):e347–e367. doi: 10.1002/phar.1353. doi: 10.1002/phar.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White C, Louis B, Persky A, et al. Institutional strategies to achieve diversity and inclusion in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(5):97–104. doi: 10.5688/ajpe77597. doi: 10.5688/ajpe77597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tapia, A. The Inclusion Paradox: The Obama Era and the Transformation of Global Diversity (pp. 12). Lincolnshire, IL: Hewitt Associates; 2009.

- 14. Peterson MW, Spencer MG. Understanding academic culture and climate. In W. G. Tierney (Ed.), Assessing academic climates and cultures. New directions for institutional research (No. 68, pp. 3–18). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1990.

- 15. Williams DA. Campus Climate & Culture Study: Taking Strides toward A Better Future, Final Report, Gloriday Gulf Coast University, Center for Strategic Diversity Leadership & Change Inc.; 2010.

- 16.The Professional Studies Program at Notre Dame de Namur University. Campus Climate Survey. https://ndnuprofessionalstudies.wordpress.com/2015/05/05/campus-climate-survey/. Published on May 5, 2015. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- 17. Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity and Inclusion in Academic Medicine: A Strategic Planning Guide. Second edition. Washington, DC: AAMC;2016.

- 18.Woods-Giscombe CL, Rowsey PJ, Kneipp SM, Owens CW, Sheffield KM, Galbraith KV, et al. Underrepresented students' perspectives on institutional climate during the application and admission process to nursing school. J Nurs Educ. 2015;54(5):261–269. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20150417-03. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20150417-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aalboe JA, Harper C, Beeman CS, Paaso BA. Dental school application timing: Implications for full admission consideration and improving diversity of dental students. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(4):575–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. PharmCAS Resources. 2016-2017 PharmCAS School Manual. http://www.aacp.org/resources/studentaffairspersonnel/admissionsguidelines/pharmcasdata/Pages/default.aspx. Updated March 27, 2017. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- 21.Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The Role of Socioeconomic Status in Medical School Admissions: Validation of a Socioeconomic Indicator for Use in Medical School Admissions. Academic Medicine. 2015;90(7):953–960. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lopez N, Wadenya R, Berthold P. Effective recruitment and retention strategies for underrepresented minority students: Perspectives from dental students. J Dent Educ. 2003;67(10):1107–1112. [PubMed]

- 23. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Institutional Research Report Series. Profile of Pharmacy Students Fall 1995. Alexandria, VA: AACP;1996.

- 24. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Institutional Research Report Series. Profile of Pharmacy Students Fall 2015. Alexandria, VA: AACP;2016.

- 25.Etowa JB, Foster S, Vukic AR, Wittstock L, Youden S. Recruitment and retention of minority students: Diversity in nursing education. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2005;2:Article 13. doi: 10.2202/1548-923x.1111. doi: 10.2202/1548-923x.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersen RM, Friedman JA, Carreon DC, Bai J, Nakazono TT, Afifi A, et al. Recruitment and retention of underrepresented minority and low-income dental students: Effects of the pipeline program. J Dent Educ. 2009;73(2 Suppl):S238–58. S375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.University of California. San Francisco School of Pharmacy. Interprofessional Health Post-Baccalaureate Certificate Program. https://pharmd.ucsf.edu/admissions/postbacc. Accessed April 3, 2017.

- 28.Giordani B, Edwards AS, Segal SS, Gillum LH, Lindsay A, Johnson N. Effectiveness of a formal post-baccalaureate pre-medicine program for underrepresented minority students. Acad Med. 2001;76(8):844–848. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200108000-00020. Aug. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Figueroa O. The significance of recruiting underrepresented minorities in medicine: an examination of the need for effective approaches used in admissions by higher education institutions. Med Educ Online. 2014;19 doi: 10.3402/meo.v19.24891. 10.3402/meo.v19.24891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.University of Maryland. Baltimore County. Meyerhoff Scholars Program. http://meyerhoff.umbc.edu/about/model/. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- 31.Woodhouse K. Collaboration or Merger? Inside Higher Ed. November 23, 2015. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/11/23/maryland-says-collaboration-not-merger-best-solution-end-higher-education. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- 32.U.SDepartment of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration. Bureau of Health Workforce, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Sex, Race, and Ethnic Diversity of U.S. Health Occupations (2010-2012). January 2015. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/diversityushealthoccupations.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- 33. Rodriguez JE, Campbell KM, Fogarty, JP, Williams RL. Underrepresented Minority Faculty in Academic Medicine: A Systematic Review of URM Faculty Development. Family Medicine. 2014 Feb; 46(2). [PubMed]

- 34.Kosoko-Lasaki O, Sonnino RE, Voytko ML. Mentoring for women and underrepresented minority faculty and students: experience at two institutions of higher education. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(9):1449–1459. Sep. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cropsey KL, Masho SW, Shiang R, Sikka V, Kornstein SG, Hampton CL, et al. Why Do Faculty Leave? Reasons for Attrition of Women and Minority Faculty from a Medical School: Four-Year Results. Journal of Women's Health. 2008;17(7):1111–1118. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0582. Sept. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freeman BK, Landry A, Trevino R, Grande D, Shea JA. Understanding the Leaky Pipeline: Perceived Barriers to Pursuing a Career in Medicine or Dentistry Among Underrepresented-in-Medicine Undergraduate Students. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):987–989. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001020. Jul. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loftin C, Newman SD, Dumas BP, Gilden G, Bond ML. Perceived Barriers to Success for Minority Nursing Students: An Integrative Review. ISRN Nurs. 2012;2012:806543. doi: 10.5402/2012/806543. doi: 10.5402/2012/806543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holden L, Rumala B, Carson P, Siegel E. Promoting careers in health care for urban youth: What students, parents and educators can teach us. Inf Serv Use. 2014;34(3-4):355–366. doi: 10.3233/ISU-140761. Jan 1. doi: 10.3233/ISU-140761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doyle WR. Does Merit-Based Aid “Crowd Out” Need-Based Aid? Research in Higher Education. 2010;51(5):397–415. Aug. doi: 10.1007/s11162-010-9166-3. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albarazi H. White House Proposes Immediate Cuts To Pell Grants, HIV Research, Food Assistance. CBS San Francisco Bay Area. March 2017. http://sanfrancisco.cbslocal.com/2017/03/29/congresswoman-rebukes-white-house-proposal-to-cut-2017-pell-grants-hiv-research/. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- 41.Giancola J, Kahlenberg RD. True Merit: Ensuring Our Brightest Students Have Access to Our Best Colleges and Universities. Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, January 2016. http://www.jkcf.org/assets/1/7/JKCF_True_Merit_Report.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- 42.August L, Waltman J. Culture, Climate, and Contribution: Career Satisfaction Among Female Faculty. Research in Higher Education. 2004;45(2):177–192. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosser VJ. Measuring the Change in Faculty Perceptions over Time: An Examination of Their Worklife and Satisfaction. Research in Higher Education. 2005;46(1):81–107. Feb. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smesny AL, Williams JS, Brazeau GA, Weber RJ, Matthews HW, Das SK. Barriers to Scholarship in Dentistry, Medicine, Nursing, and Pharmacy Practice Faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(5):Article 91. doi: 10.5688/aj710591. doi: 10.5688/aj710591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Strategic Plan 2016–2019: Mission Driven Priorities. http://www.aacp.org/about/Pages/StrategicPlan.aspx. Updated March 17, 2017. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- 46.Awe C, Bauman L. Theoretical and conceptual framework for a high school pathways to pharmacy program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(8):Article 149. doi: 10.5688/aj7408149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leonhardt D American’s Great Working-Class Colleges. New York Times, Sunday Review. January 18, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/18/opinion/sunday/americas-great-working-class-colleges.html?smid=tw-share&_r=0. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- 48.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Student Applications, Enrollments and Degrees Conferred. http://www.aacp.org/resources/research/institutionalresearch/Pages/StudentApplications,EnrollmentsandDegreesConferred.aspx. Updated April 5, 2016. Accessed October 18, 2016.