Abstract

Importance

Prescription opioids play an important role in the treatment of post-operative pain, yet unused opioids may be diverted for non-medical use and contribute to opioid-related injuries and deaths.

Objective

To quantify how commonly post-operative opioids are unused, why they remain unused, and practices regarding their storage and disposal after surgery.

Evidence Review

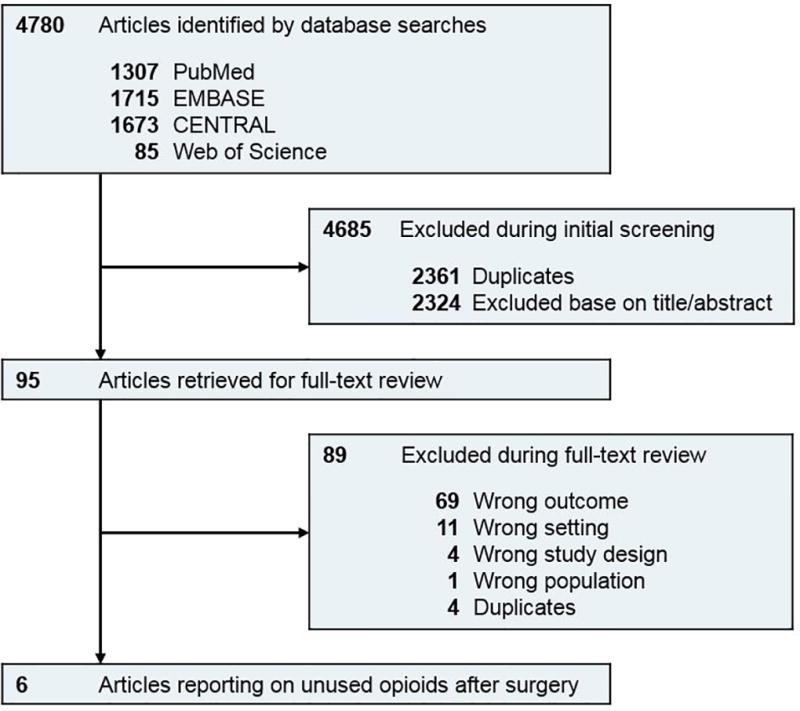

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from inception to 18 October 2016 for studies describing opioid over-supply for adults after any surgery or procedure. We defined our primary outcome, opioid over-supply, as the number of patients with either filled prescriptions with unused opioids or unfilled opioid prescriptions. Two reviewers independently screened studies for inclusion, extracted data, and assessed study quality.

Findings

Six eligible studies reported on a total of 810 patients (range 30–250) undergoing seven different procedure types. Across the six studies, between two-thirds (67%) to nine-tenths (92%) of patients reported unused opioids. Among opioids obtained by surgical patients, 42% to 71% of all tablets went unused. A majority of patients stopped or used no opioids due to adequate pain control, while 16% to 29% of patients reported opioid-induced side effects. In two studies examining storage safety, 73% to 77% of patients reported that their prescription opioids were not stored in locked containers. All studies reported low rates of anticipated or actual disposal, while no study reported FDA-recommended disposal methods in more than 9% of patients.

Conclusions & Relevance

Post-operative prescription opioids often go unused, unlocked, and undisposed, suggesting an important reservoir of opioids contributing to non-medical use of these products.

INTRODUCTION

Opioids play an important role as a safe and effective method for pain relief when used appropriately. Despite this, the benefits of opioids in treating pain have to be balanced with their risks, including tolerance, dependence, and respiratory depression. Non-medical use of opioids, defined as taking medication for a purpose other than as prescribed, often leads to more serious harms such as abuse, addiction or life-threatening overdose. To address the opioid epidemic, efforts have largely focused on opioid prescribing among those with chronic non-cancer pain.1 In contrast, the risks and evidence for patients with acute pain following surgery are less well characterized.2

Surgery often serves as the inaugural event for many patients to obtain a prescription for opioids, fill it at the pharmacy, and take opioid medications on a frequent basis. Prescriptions may go unfilled for reasons including adequate pain control after surgery. When prescriptions are filled, opioid naïve patients may inadvertently transition into long-term opioid users.3, 4 Low-risk surgical procedures give rise to a majority of opioid-naïve patients receiving and filling prescriptions for oxycodone, hydrocodone, or another opioid.5 Patients may fill the prescription but not use all of the medication, leading to a reservoir of pills that can potentially contribute to the non-medical use of opioids.

Given the lack of data-driven approaches to opioid prescribing after surgery, we conducted a systematic review to examine the prevalence of unused prescription opioids among home-going adults following inpatient or outpatient surgery. We defined our primary outcome as the number of patients reporting any unused opioids, defined as the number of patients who either elected to not fill an opioid prescriptions or who had unused opioid medications after filling an opioid prescription following surgery. We also examined the volume of unused opioids, reasons for not taking the medication, and storage and disposal practices.

METHODS

Data Sources and Search

We adhered to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses guidelines, including protocol registration with PROSPERO on June 9, 2016 (#42016042656).6 We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library without language restriction from inception to July 20, 2016, and updated the search on October 18, 2016. For studies fulfilling inclusion criteria, we also searched citation lists and citing studies using Web of Science to the same date. We created a search strategy using controlled vocabulary of known studies meeting inclusion criteria and focused on specific terms related to the concepts of adults (population), opioids (intervention), surgery/procedure (intervention), and medication use and prescription (outcome; eMethods).

Inclusion Criteria and Outcome Definition

We included cross-sectional and cohort studies and randomized controlled trials of adult surgical patients who were prescribed an oral opioid medication by a medical provider at time of post-surgical discharge. We included both inpatient and outpatient procedures and did not apply any restrictions regarding surgery type. We required studies to report on unused opioid medication defined as filled prescriptions or unused tablets. We excluded retrospective studies, those that described non-surgical or pediatric (age <18 years) patients, and studies that did not report the outcome of unused opioids.

We calculated the percent of patients who had an over-supply of a prescription opioid as the sum of patients not filling opioid prescriptions and patients filling opioid prescriptions who reported unused opioids. For the denominator, we used the number of patients provided an opioid prescription after surgery. Secondary outcomes included the number of opioid tablets (or volume of solution) unused by the patient, morphine-equivalents of prescription opioid medication unused by the patients, reasons for not using or stopping opioids, and storage and disposal characteristics of opioids.

Two reviewers independently assessed 2,419 non-duplicate studies, with 2,324 studies failing title and abstract screening. Of the 95 studies retrieved and assessed by two authors, six fulfilled inclusion criteria (eFigure 1, kappa 0.78).

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two authors independently extracted relevant study characteristics using a data extraction template. Data included study design, setting, patient population, type of surgery, opioid prescription characteristics, unused opioid tablets, reasons for stopping or not using opioids, and storage and disposal characteristics. Storage characteristics included location and use of lock to secure opioids based on FDA and CDC guidelines.1, 7 For disposal, FDA-recommended methods included return to pharmacy/drug take-back program or flushing medication down sink/toilet. Two reviewers assessed the quality of studies and potential bias using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale8 adapted for observational studies or the Cochrane risk of Bias Tool9 for clinical trials. Disagreements between reviewers regarding data extraction and quality assessment ratings were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Data Synthesis

We aggregated extracted data by type of surgery, reporting on study characteristics, opioid utilization, reasons for opioid cessation, and storage and disposal characteristics. We qualitatively summarized outcomes across surgery type due to differences in patient populations, which precluded quantitative data pooling.

RESULTS

After full-text review, six studies met our pre-specified inclusion criteria, with all studies describing populations in the United States (Table 1, eTable).10–15 Among the prospective studies considered for this review, we identified duplicate reports for one study15, 16 and excluded three others17–19 because of an inability to distinguish surgical from non-surgical reports of unused opioid medications.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies assessing unused opioids after surgery

| Study, year | Study design | Setting | Procedure types | Population | Patients n |

Female n (%) |

Study length days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bartels et al, 2016 | Cross-sectional | Univ. of Colorado | Cesarean section | Inpatient | 30 | 30 (100) | 30 ± 12 |

| Bartels et al, 2016 | Cross-sectional | Univ. of Colorado | Thoracic surgery | Inpatient | 31 | 16 (52) | 32 ± 14 |

| Bates et al, 2013 | Cross-sectional | Univ. of Utah | Urologic surgery | Mixed | 226 | - | - (14 to 28) |

| Harris et al, 2013 | Prospective cohort | Univ. of Utah | Dermatologic surgery | Outpatient | 72 | 20 (28) | - (3 to 4) |

| Hill et al, 2016 | Cross-sectional | Dartmouth Medical Ctr. | General surgery | Outpatient | 127 | - | - (- to 180) |

| Maughan et al, 2016 | RCT | Univ. of Pennsylvania | Dental surgery | Outpatient | 74 | - | 21 |

| Rodgers et al, 2012 | Cross-sectional | Private practice, Iowa | Orthopedic surgery | Outpatient | 250 | 167 (67) | 11 (7 to 14) |

Ctr. = Center; RCT = randomized controlled trial; Univ. = University

Six eligible studies prospectively evaluated the over-supply of opioids after seven types of surgery, including obstetrical, thoracic, orthopedic, and urologic surgery. Practice settings described surgeons employed by four institutions and one private practice between the years 2011 and 2016. Studies primarily evaluated outpatient procedures (n = 4), with fewer reports of inpatient (n = 2) or mixed (n = 1) procedures. In all, 810 patients received at least one opioid prescription after surgery. Patient samples ranged in size from 30 for cesarean section to 250 for orthopedic surgery. Duration of follow up most commonly ranged from 1 to 5 weeks after surgery.

All six studies were rated as of intermediate quality. Reporting of baseline characteristics important for comparability, such as pre-procedural use of opioid medications, varied among the studies: three studies excluded patients based on pre-procedural opioid use (within 7 or 30 days),13–15 one study assessed and reported pre-procedural use via self-report,10 and two studies neither excluded such patients nor recorded this characteristic.11, 12

Opioid over-supply

The prevalence of unused opioids after surgery was high for all seven procedures examined, with 67% to 92% of patients reporting unused opioids (Figure 1). Table 2 highlights the primary outcome and related secondary outcomes. Patients reported large amounts of unused opioids following both outpatient (77% to 92%) and inpatient surgery (67% to 90%). In five of the seven surgical settings examined, more than 80% of patients reported unused opioids. Three studies examined reports of filling a prescription with no opioid use and reports of not filling the opioid prescription, while two studies examined only the latter outcome. A small number of patients either did not fill their opioid prescription (0% to 21%) or filled the prescription but did not take any opioids (7% to 14%). A significant number of opioid tablets went unused after surgery, ranging from 42% to 71% of pills dispensed.

Figure 1. Prevalence of unused opioids prescribed after surgery.

Percentage reporting use of ≤ 15 tablets was used for Rodgers et al, 2012.

Table 2.

Utilization in studies assessing unused opioids after surgery

| Study, year | Patients, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Any unused opioids |

Unfilled opioid prescriptions |

Filled prescription with no opioid use |

Unused opioid tablets | ||

|

| |||||

| n(%) | mean | ||||

| Bartels et al, 2016 | 27/30 (90) | 4/30 (13) | 2/30 (7) | - | - |

| Bartels et al, 2016 | 25/31 (81) | 0/31 (0) | 3/31 (10) | - | - |

| Bates et al, 2013 | - (67) | 13/226 (6) | - | - (42) | - |

| Harris et al, 2013 | 64/72 (89) | 15/72 (21) | 10/72 (14) | - (68) | 5 ± 4 |

| Hill et al, 2016 | 117/127 (92) | - | - | 2527/3545 (71) | 20 |

| Maughan et al, 2016 | 67/74 (91) | 2/74 (3) | - | 1102/2051 (54) | 15 |

| Rodgers et al, 2012 | 193/250 (77)A | - | - | 4639/ - | 19 |

Percentage reporting use of ≤ 15 tablets; “- “ = not reported

Reasons for not consuming opioid medications were reported for three types of procedures (Table 3). Most patients (71% to 83%) described not taking opioids due to adequate pain control, while fewer reported concern for side effects induced by opioids (16% to 29%). Only one study examined patients’ concern about addiction, with 8% of thoracic surgery patients avoiding opioids for this reason.10

Table 3.

Patient-reported reasons for not using or stopping opioids after surgery

| Study, year | Patients, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Adequate pain control |

Side effects | Concern for addiction |

Other | |

| Bartels et al, 2016 | 19/23 (83) | 4/23 (17) | - | 4/23 (17) |

| Bartels et al, 2016 | 17/24 (71) | 7/24 (29) | 2/24 (8) | 4/24 (17) |

| Rodgers et al, 2012 | - | 40/250 (16) | - | - |

Storage and Disposal

Patients’ storage of prescription opioids was characterized for two types of surgery, focusing on cesarean section and thoracic surgery (Table 4). A majority of patients stored opioids in a medicine cabinet or other box (54% to 70%), followed by a cupboard or wardrobe (21% to 26%). Notably, a high percentage of patients stored opioids in unlocked locations (73% to 77%). Five studies examined patients’ opioid disposal practices, with a minority of patients (4% to 30%) planning to or actually disposing of their unused prescription opioids. Even fewer patients (4% to 9%) considered or employed a method recommended by the Food and Drug Administration.

Table 4.

Storage and disposal characteristics for unused opioids after surgery

| Study, year | Patients, n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Storage | Disposal | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Location | Unlocked storage |

Performed or planned |

FDA- recommended method used |

No disposal instructions |

||

| Bartels et al, 2016 | 6/23 (26) | Cupboard/wardrobe | 17/22 (77) | 1/23 (4) | 1/23 (4) | - |

| 16/23 (70) | Medicine cabinet/other box | |||||

| Bartels et al, 2016 | 5/24 (21) | Cupboard/wardrobe | 16/22 (73) | 2/24 (8) | 1/24 (4) | - |

| 13/24 (54) | Medicine cabinet/other box | |||||

| Bates et al, 2013 | - | - | 15/164 (9) | 5/164 (3) | 213/231 (92) | |

| Harris et al, 2013 | - | - | 9/49 (18) | 2/49 (4) | - | |

| Hill et al, 2016 | - | - | - (26) | - (9) | - | |

| Maughan et al, 2016 | - | - | 8/27 (30)A | - | - | |

Based on control group

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, more than two-thirds of patients reported unused prescription opioids following surgery. These findings were consistent across several studies of general, orthopedic, thoracic and obstetric inpatient and outpatient surgeries. Of the five studies examining storage and disposal practices, three in four patients reported failing to store opioids in a locked location and planned or actual safe disposal of opioids rarely occurred. These findings are important because of the magnitude of injuries and deaths attributable to the non-medical use of prescription opioids in the United States, and the contribution that the over-supply of these products makes to this epidemic.

There are several factors that likely contribute to how commonly patients report unused opioid medications. Providers may not be aware of how commonly opioids go unused2, and heterogeneous patient populations and procedure types complicate the development of evidence-based prescribing guidelines in these settings. However, some patient reported outcomes and psychological profiles may inform pain intensity and subsequent analgesic use after surgery. For example, Thomazeau et al. correlated post-operative pain for total knee arthroplasty with preoperative pain at rest, anxiety levels and symptoms of neuropathic pain.20 In another example, Carvalho et al. associated pain scores and analgesic use for women after cesarean delivery with psychological questionnaires and simple patient-reported ratings.21

We recommend a data-driven approach to prescribing of opioids after surgery. An inappropriate response to the problem of unused opioids would be to pursue a reflexive, “one size fits all” tactic that indiscriminately curtails opioid prescribing after invasive procedures, given the critical consequences of pain under-treatment, the possibility of inducing drug-seeking behavior, and the important role that opioid medications serve in controlling post-operative pain.2, 22 As providers encounter new regulations such as prescription drug monitoring programs in most states and electronic prescribing requirements in New York,23 the evidence associated with these interventions continues to evolve.24 At a national level, guidelines emphasize the importance of non-opioid analgesics such as acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and gabapentoids, as well as non-pharmacologic approaches such as exercise, cold, and heat.2, 25

We also found that opioids were seldom stored and disposed of correctly. Safe storage practices mitigate risks for other household members, such as adolescents at risk of misusing medication accessible in the house.26, 27 The failure to properly dispose of opioids highlights the role of stockpiling as an important contributor to their non-medical use. Stockpiling is common, given the time and energy involved with proper disposal practices. Besides cost, patients may perceive a future utility for opioids, in that pain medication will relieve acute pain should it return in the future. Medication take-back programs help to address the over-supply of tablets sitting around the house.28 Pharmacies and health systems facilitate the capture of an enormous amount of drug products during DEA-sanctioned take back days, community-based collection events,29 and coordinated programs such as National Prescription Drug Drop-Off Day in Canada.30 Yet these events secure only a small fraction of opioids available for non-medical use and remain in rudimentary stages of implementation.31 Pharmacies appear as one possible solution but assume unwanted costs and liabilities in taking back scheduled medications. Few commercial solutions (e.g., disposal bags) exist, relegating patients to flushing opioids down the sink or toilet, which may reduce individual risk at the expense of the environment.

The combination of unused opioids, poor storage practices, and lack of disposal sets the stage for the diversion of opioids for non-medical use. Based on the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, an estimated 3.8 million Americans engage in the non-medical use of opioids every month.32 More than half of people (54%) who misused an opioid medication in the past year obtained opioids from a friend or relative.33 Most of these pills were either given for free, bought, or taken without asking. The second largest source of misused opioids (36%) was directly via a prescription from one or more healthcare providers.33 Because more than 90% of opioids originate from medical providers, family, or friends, the over-supply of opioids in healthcare environments that appear otherwise innocuous deserves additional scrutiny.

Despite the importance of our findings, our review had several limitations. First, the studies we examined were of intermediate rather than high methodological quality, and questionnaires completed by patients varied in form, structure, phrasing, and timing across the studies. Many studies also failed to ascertain history of opioid use among respondents and did not describe essential features for cross-sectional and cohort studies such as non-respondents and missing data. Evidence gaps also exist for surgical subspecialties besides the seven types reported here, as well as for individual surgeries. Second, we were not able to estimate leftover morphine equivalents for these patients, since this information was not reported in any of the studies examined, or examine more granular data regarding unused opioid pill counts to determine a consistent, clinically relevant definition of unused opioids. Data on additional surgical subspecialties would enhance the generalizability of these findings, which largely agree with most estimates of non-surgical opioid prescribing in acute, chronic, or both types of pain. For example, Porucznik et al. showed similarly high rates of leftover opioids among adults prescribed opioids.18 Regarding storage, Reddy et al. showed similar rates of unlocked medication in cancer patients prescribed opioids.19 Finally, heterogeneity across the studies precluded any quantitative pooling of the results.

In conclusion, the majority of patients undergoing surgery in these studies had unused prescription opioids, while safe storage and disposal of unused medicines rarely occurred. Increased efforts are needed to develop and disseminate best practices to reduce the over-supply of opioids after surgery, especially given how commonly opioid analgesics prescribed by clinicians are diverted for non-medical use.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question

How commonly are post-surgical prescription opioids unused among adults after discharge?

Findings

Between two-thirds to nine-tenths of patients reported unused opioids following a diverse group of orthopedic, thoracic, obstetric and general surgeries. Rates of safe storage and/or disposal of unused prescription opioids were low.

Meaning

Opioids prescribed for patients after surgery are an important reservoir of these products available for non-medical use.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Alexander is Chair of the FDA’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee; serves as a paid consultant to PainNavigator, a mobile startup to improve patients’ pain management; serves as a paid consultant to QuintilesIMS, and serves on an QuintilesIMS Health scientific advisory board.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. Mark Bicket, Jane Long, Peter Pronovost, and Christopher Wu declare that they have no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

Access to Data and Data Analysis: Mark Bicket had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis

References

- 1.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624–1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of Postoperative Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists' Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2016;17(2):131–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Bell CM. Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Archives of internal medicine. 2012;172(5):425–430. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Chronic Opioid Use Among Opioid-Naive Patients in the Postoperative Period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1286–1293. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wunsch H, Wijeysundera DN, Passarella MA, Neuman MD. Opioids Prescribed After Low-Risk Surgical Procedures in the United States, 2004–2012. Jama. 2016;315(15):1654–1657. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Food and Drug Administration. Disposal of unused medicines: what you should know. [Accessed January 17, 2016]; http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsingMedicineSafely/EnsuringSafeUseofMedicine/SafeDisposalofMedicines/ucm186187.htm#Flush_List.

- 8.Herzog R, Alvarez-Pasquin MJ, Diaz C, Del Barrio JL, Estrada JM, Gil A. Are healthcare workers' intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartels K, Mayes LM, Dingmann C, Bullard KJ, Hopfer CJ, Binswanger IA. Opioid Use and Storage Patterns by Patients after Hospital Discharge following Surgery. PloS one. 2016;11(1):e0147972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bates C, Laciak R, Southwick A, Bishoff J. Overprescription of postoperative narcotics: a look at postoperative pain medication delivery, consumption and disposal in urological practice. The Journal of urology. 2011;185(2):551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris K, Curtis J, Larsen B, et al. Opioid pain medication use after dermatologic surgery: a prospective observational study of 212 dermatologic surgery patients. JAMA dermatology. 2013;149(3):317–321. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodgers J, Cunningham K, Fitzgerald K, Finnerty E. Opioid consumption following outpatient upper extremity surgery. The Journal of hand surgery. 2012;37(4):645–650. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill MV, McMahon ML, Stucke RS, Barth RJ., Jr Wide Variation and Excessive Dosage of Opioid Prescriptions for Common General Surgical Procedures. Ann Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maughan BC, Hersh EV, Shofer FS, et al. Unused opioid analgesics and drug disposal following outpatient dental surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maughan BC, Hersh E, Shofer FS, et al. Leftover opioid analgesics and prescription drug disposal following outpatient dental surgery: Results of a pilot randomized controlled trial. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2016;23(SUPPL. 1):S168–S169. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis ET, Cucciare MA, Trafton JA. What Do Patients Do With Unused Opioid Medications? Clinical Journal of Pain. 2014;30(8):654–662. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000435447.96642.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porucznik CA, Sauer BC, Johnson EM, et al. Adult Use of Prescription Opioid Pain Medications - Utah, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59(6):153–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reddy A, de la Cruz M, Rodriguez EM, et al. Patterns of Storage, Use, and Disposal of Opioids Among Cancer Outpatients. Oncologist. 2014;19(7):780–785. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomazeau J, Rouquette A, Martinez V, et al. Acute pain Factors predictive of post-operative pain and opioid requirement in multimodal analgesia following knee replacement. Eur J Pain. 2016;20(5):822–832. doi: 10.1002/ejp.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carvalho B, Zheng M, Harter S, Sultan P. A Prospective Cohort Study Evaluating the Ability of Anticipated Pain, Perceived Analgesic Needs, and Psychological Traits to Predict Pain and Analgesic Usage following Cesarean Delivery. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2016;2016:7948412. doi: 10.1155/2016/7948412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu CL, Raja SN. Treatment of acute postoperative pain. Lancet. 2011;377(9784):2215–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60245-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.New York State Department of Health. Electronic Prescribing. [Accessed January 17, 2017]; https://www.health.ny.gov/professionals/narcotic/electronic_prescribing/

- 24.Rutkow L, Chang HY, Daubresse M, et al. Effect of Florida's Prescription Drug Monitoring Program and Pill Mill Laws on Opioid Prescribing and Use. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1642–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(2):248–73. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823c1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross-Durow PL, McCabe SE, Boyd CJ. Adolescents' access to their own prescription medications in the home. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(2):260–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCabe SE, West BT, Cranford JA, et al. Medical misuse of controlled medications among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(8):729–735. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray JA, Hagemeier NE. Prescription drug abuse and DEA-sanctioned drug take-back events: characteristics and outcomes in rural Appalachia. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(15):1186–1187. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perry LA, Shinn BW, Stanovich J. Quantification of ongoing community-based medication take-back program. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 2014;54(3):275–279. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2014.13143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu PE, Juurlink DN. Unused prescription drugs should not be treated like leftovers. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2014;186(11):815–816. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perry LA, Shinn BW, Stanovich J. Quantification of an ongoing community-based medication take-back program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2014;54(3):275–279. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2014.13143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. [Accessed 27 Oct, 2016];2016 http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015.pdf.

- 33.Hughes AWM, Lipari RN, Bose J, Copello EAP, Kroutil LA. Prescription drug use and misuse in the United States: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. [Accessed 26 Oct, 2016];NSDUH Data Review. 2016 http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR2-2015/NSDUH-FFR2-2015.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.