Abstract

Line bisection has long been a routine test for unilateral neglect, along with a range of tests requiring cancellation, copying or drawing. However, several studies have reported that line bisection, as classically administered, correlates relatively poorly with the other tests of neglect, to the extent that some authors have questioned its status as a valid test of neglect. In this article, we re-examine this issue, employing a novel method for administering and analysing line bisection proposed by McIntosh et al. (2005). We report that the measure of attentional bias yielded by this new method (EWB) correlates significantly more highly with cancellation, copying and drawing measures than the classical line bisection error measure in a sample of 50 right-brain damaged patients. Furthermore when EWB was combined with a second measure that emerges from the new analysis (EWS), even higher correlations were obtained. A Principal Components Analysis found that EWB loaded highly on a major factor representing neglect asymmetry, while EWS loaded on a second factor which we propose may measure overall attentional investment. Finally, we found that tests of horizontal length and size perception were related poorly to other measures of neglect in our group. We conclude that this novel approach to interpreting line bisection behaviour provides a promising way forward for understanding the nature of neglect.

Keywords: Attention, Unilateral neglect, Line bisection, Cancellation

Highlights

-

•

We used novel measures of attentional allocation to study line bisection behaviour in 50 right-brain damaged patients.

-

•

These measures were more sensitive to neglect than was directional bisection error, and they correlated more highly with other core tests of neglect.

-

•

We propose that one measure (EWB) reflects a lateral bias of attention, and the other measure (EWS) reflects overall attention.

-

•

Perceptual biases on size-matching and landmark tasks did not correlate highly with line bisection, or any other core tests of neglect.

1. Introduction

Horizontal line bisection is a simple task used widely in the diagnosis and study of visual neglect (Axenfeld, 1915, Schenkenberg et al., 1980). The brain-damaged patient is asked to mark the midpoint of a presented line, and substantial deviation from the true centre is taken to indicate neglect for the opposite side of space. This task requires minimal materials, is quick to administer, and in its classical form of analysis, in which an average directional error is taken, yields a single continuous measure of asymmetry. In developing their standardised battery of diagnostic tests for neglect, Halligan et al. (1989) included line bisection as a core test, along with target cancellation, figure copying and free drawing.

A common assumption has been that line bisection is a test of length perception, tapping into the visuospatial experience of the patient (e.g. Schenkenberg, 1980). Under this assumption, the average directional bisection error is an estimate of the patient's subjective midpoint, and therefore of any perceptual asymmetry. [It is true that during the 1990s some research groups suggested that extreme bisection errors can sometimes reflect a motoric rather than (or in addition to) a perceptual bias (Bisiach et al., 1990; Bisiach et al., 1998; Coslett et al., 1990; Harvey et al., 1995a, Harvey et al., 1995b; Milner et al., 1993; Tegnér and Levander, 1991). Nonetheless, average directional error was always the standard measure taken to characterise behaviour.]

1.1. A novel approach

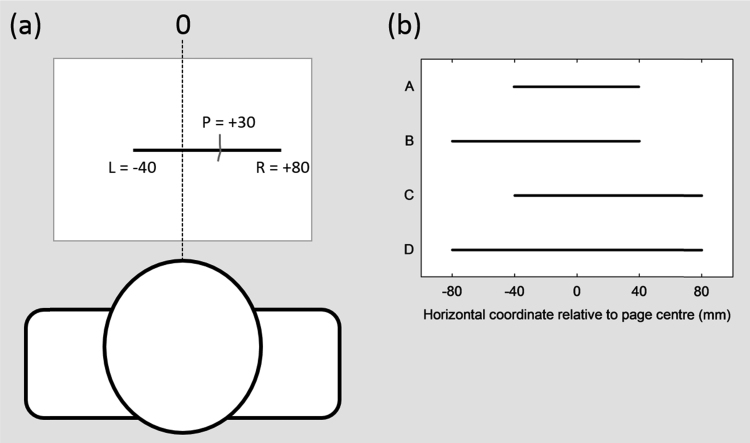

There is an alternative way to elicit and analyse bisection data, one that emphasizes the trial-to-trial variations of behaviour rather than taking an average score. This novel approach, proposed by McIntosh et al. (2005) avoids the assumption that the patient's response reflects a meaningful subjective midpoint; that is, no special status is given to the deviation from the true midpoint (i.e. directional bisection error). Instead, as illustrated in Fig. 1a, each response is coded simply as a horizontal coordinate relative to a fixed environmental location (such as the midline of the sheet). The analysis then focuses on how this response position varies from trial-to-trial as a consequence of changes in the positions of the left and right endpoints of the line. Across trials, the left and right endpoint positions are manipulated orthogonally, for instance using a set of four stimulus lines created by crossing two possible locations of each endpoint (Fig. 1b). The influence of each endpoint on the response (the ‘endpoint weighting’) can then be calculated: the right endpoint weighting is the average change in the response that accompanies the change in the right endpoint, expressed as a proportion of the endpoint change, and vice-versa for the left endpoint.

Fig. 1.

The endpoint weightings format of line bisection. (a) The stimulus sheet with a single line is placed directly in front of the patient, who is asked to bisect the line by marking a position (P). In the traditional task analysis, the line in this example would be considered as 120 mm long, displaced 20 mm towards the right hemispace, and the patient's response would be scored as a +10 mm deviation from the true midpoint of the line. In the endpoint weightings analysis, the positions of the response (P) and of the left (L) and right (R) endpoints are coded as horizontal coordinates relative to a fixed environmental reference, in this case the centre of the page (0). The patient in this example has responded at +30 mm, with L at −40 mm and R at +80 mm. (b) In a basic version of the endpoints line bisection task, a set of stimulus lines (A-D) is generated by crossing two positions of L (−40, −80) with two positions of R (+40, +80). Each line is presented individually, with eight repetitions for each stimulus line. The analysis focuses on how P varies as a consequence of changes in L (lines A&C vs B&D) or changes in R (lines A&B vs C&D). See Methods for full details.

If the bisection task were performed perfectly, then a shift in one endpoint location would be accompanied by a shift in the response half as large in the same direction (e.g. moving the right endpoint to the right by 40 mm would cause the bisection response to shift to the right by 20 mm). Perfect performance would thus yield symmetrical right and left endpoint weightings of 0.5. McIntosh et al. (2005) reported that a group of 30 healthy older participants approached this ideal, albeit with a slightly but significantly higher weighting for the left endpoint than for the right (0.51 vs 0.48). In contrast, in 30 patients with left neglect, the left endpoint weighting was almost always lower than the right, indicating that the response was more influenced by the right endpoint than by the left. In extreme cases, the left endpoint weighting approached zero and the right endpoint weighting approached one, meaning that the response essentially maintained a constant distance from the right endpoint (cf. Koyama et al., 1997). These patterns have now been replicated in a further 12 patients with left neglect (McIntosh, 2017).

This novel analysis of line bisection has some noteworthy properties. First, a simple measure of lateral asymmetry, the endpoint weightings bias (EWB), given by the subtraction of the left endpoint weighting from the right endpoint weighting, identifies neglect in a higher proportion of patients than does the standard measure of bisection error (McIntosh et al., 2005; McIntosh, 2017). That is, EWB can expose an under-weighting of the left relative to the right endpoint in patients who bisect within normal limits, or even in patients who bisect abnormally leftwards. Similarly, the linear combination of these left and right endpoint weightings accurately predicts that some left neglect patients will make leftward (“crossover”) bisections for short lines and/or for lines presented toward the right side of the sheet (McIntosh et al., 2005). In other words, some apparently ‘anomalous’ bisections are no longer anomalous when viewed within an endpoint weightings framework. As originally articulated by Kinsbourne (1993), rightward or leftward errors of bisection can result from a lack of awareness of the left endpoint of the line (p. 72).

A second noteworthy property is that, because the ideal value of each endpoint weighting is known (0.5), we may state whether each endpoint receives too much or too little weight in absolute terms. It is therefore potentially informative to calculate the total weighting across the two endpoints: the endpoint weightings sum (EWS). Healthy older participants score close to one on this index, but patients with neglect very often score lower (McIntosh et al., 2005; McIntosh, 2017). If we propose that an endpoint weighting reflects the attention allocated to each side of the line, then a reduced EWS would indicate reduced overall attentional allocation. Regardless of its precise theoretical interpretation, EWS is a non-lateralised measure that can again discriminate patients from controls (McIntosh et al., 2005). These two measures, EWB and EWS, fall readily from the ‘endpoint weightings’ format of the line bisection task, in which left and right endpoint positions are varied independently.1

1.2. Relation to other measures of neglect

There has been disagreement over the extent to which the classical directional bisection error correlates with other measures of neglect. Initially, Halligan et al. (1989) reported that bisection performance correlated strongly with their other core tests (r = 0.67 correlation with star cancellation; 0.73 with copying; 0.63 with drawing). A Principal Components Analysis (PCA) found that all core tests loaded strongly (0.85) onto a single factor accounting for 73% of the total variance, leading to the conclusion that visual neglect is – to a large extent – a single phenomenon. Since then, however, this conclusion has been seriously disputed, even by Halligan and Marshall (1992) themselves, who went so far as to declare left visual neglect ‘a meaningless entity’.

In particular, the less than perfect relationship between bisection and cancellation has been a focus of interest. Binder et al. (1992) reported a correlation of only r = 0.39 amongst 21 (of 34) right-brain damaged patients who met criteria for neglect on one or both tasks of bisection and letter cancellation. Later studies have yielded diverse estimates for the correlation between line bisection and various versions of target cancellation in neglect, ranging from r = 0.37 (Guariglia et al., 2014) to r = 0.76 (Molenberghs and Sale, 2011). This last correlation, however, was driven by three patients with strong asymmetries on both tasks: a more appropriate nonparametric correlation for their tabulated data would have returned a much less impressive Spearman ρ of only 0.26. Other estimates include r = 0.40 (Sperber and Karnath, 2016), and r = 0.49 (Ferber and Karnath, 2001), while Azouvi et al. (2002) reported a correlation of only 0.19 for 5 cm lines, but of 0.62 for 20 cm lines. These estimates, though varied, are weaker than one would expect for two core tests of a single construct.

This impression has been supported by the continued use of PCA to probe the component structure of neglect test batteries (Azouvi et al., 2002, Kinsella et al., 1993, McGlinchey-Berroth et al., 1996, Sperber and Karnath, 2016, Verdon et al., 2010). The details of these studies differ depending upon the tests and the patients sampled, but none has replicated the single-component solution that Halligan and colleagues reported in 1989, and the majority of them have assigned cancellation and bisection to separate components (Azouvi et al., 2002, McGlinchey-Berroth et al., 1996, Sperber and Karnath, 2016, Verdon et al., 2010). The most recent of these studies concluded forcefully that line bisection is not a valid task to diagnose neglect (Sperber and Karnath, 2016).

All of these previous studies used directional bisection error as their measure, derived from the classical format of the bisection task. We have argued that this approach is based on assumptions that are inappropriate for patients with neglect, and that directional bisection error may give a distorted view of neglect behaviour (McIntosh, 2006, 2017; McIntosh et al., 2005). If this is correct, then the evidence suggesting that bisection behaviour is distinct from other core aspects of the neglect syndrome needs to be re-evaluated.

1.3. The present study

We address here the status of line bisection as a test of neglect by using our measures, EWB and EWS, in place of the traditional directional bisection error. Our guiding hypothesis was that EWB should index the asymmetrical aspects of neglect, whilst EWS may index the overall strength of the person's attentional resource. Our aim was to investigate how these novel measures relate to the other core tests of neglect in a cohort of 50 right brain-damaged patients. Following previous investigators, we also used PCA to explore the underlying structure of impairments measured across our main diagnostic tasks. Finally, we re-examined the assumption that line bisection effectively tests spatial misperception in neglect. In previous research, individual comparisons between line bisection and tests of length perception have been made, with some discrepancies noted (Harvey et al., 1995a; Ishiai et al., 1994a,1994b; Marshall and Halligan, 1995). However, these relationships have not been systematically studied in larger patient groups, despite their importance for the interpretation of bisection impairment. In the present cohort of patients, we assessed the relation between line bisection and two tasks specifically targeting horizontal size and length perception.

2. Methods

2.1. Recruitment and sample

Suitable right-brain damaged patients were recruited from National Health Service (NHS) stroke units in the North East of England and in Edinburgh. Candidate patients identified by local rehabilitation staff and/or from medical records were approached to provide information about the study, then re-approached one to three days later for a decision on participation. Only patients with unilateral right hemisphere stroke, as indicated by clinical symptoms and confirmed by clinical brain imaging (as reported in the clinical notes) were considered suitable. Exclusion criteria were: previous stroke; aphasia or severe dysphasia; dementia; significant neurological comorbidity; history of alcohol abuse. There was no strict age limit, but patients more than 80 years of age were considered only where there were clear signs of neglect, and generally good cognitive function. Preference was given to patients for whom signs of neglect or extinction were recorded in the clinical notes, or suspected from researcher interactions during the information session. This means that, if practical constraints limited the number of patients that could be tested in a given timeframe, then those with suspected neglect were prioritised. This strategy was adopted to maximise the informativeness of the data about the symptoms of interest, and to limit the statistical compression effects that would result from including large numbers of patients without such symptoms.

Recruitment and testing was carried out in accordance with a protocol approved by the Northern and Yorkshire Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee, with informed consent taken at the first testing session. In total, fifty patients were tested on the complete set of tasks. Basic patient details and test scores are included in Table 1. Twelve patients additionally took part in a related experiment studying the effect of cueing on the endpoint weightings measures. These patients, listed as RBD01-RBD12 in Table 1, correspond to patients VN01-VN12 in McIntosh (2017).

Table 1.

Basic patient characteristics and scores on all tests. † appended to the patient code indicates the finding of a visual field deficit by confrontation. Time post-stroke is given in days. Lines (L/R): % omissions in each half of line crossing sheet. Stars (L/R): % omissions in each half of star cancellation sheet. Copy (sym/it): number of items copied symmetrically/number of items attempted, followed by the copying summary score. Draw (0–3): number of drawings with evidence of left neglect. Multi-bisect: mean directional bisection error on the multiple line bisection task. Bisect DBE: directional bisection error for line bisection task. Bisect EWB: endpoint weightings bias for line bisection task. Bisect EWS: endpoint weightings sum for line bisection task. Size-matching: % of ‘left-is-smaller’ responses. Landmark PSE: point of subjective equality in landmark test. Bold values indicate left neglect, and starred values indicate right neglect (see methods for cut-off criteria).

| Patient code |

Age /sex |

Post-stroke (days) |

Lines L/R |

Stars L/R |

Copy sym/it (total) |

Draw (0-3) |

Multi-bisect (mm) | Bisect DBE (mm) |

Bisect EWB |

Bisect EWS |

Size-matching (%) |

Landmark PSE (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBD01 | 68/M | 17 | 0/0 | 4/4 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | 8.9 | 2.2 | 0.01 | 1.04 | 53 | 0.0 |

| RBD02† | 59/M | 257 | 100/28 | 100/44 | 1/1 (8) | 1 | 34.0 | 12.2 | 0.50 | 0.69 | 35 | −30.3 |

| RBD03 | 67/M | 32 | 6/0 | 59/15 | 2/3 (5) | 1 | 11.9 | 1.7 | 0.26 | 0.94 | 82 | 9.8 |

| RBD04 | 59/M | 43 | 6/0 | 100/4 | 5/5 (0) | 2 | −2.1 | −0.2 | 0.02 | 0.88 | 80 | −0.2 |

| RBD05 | 87/M | 45 | 39/0 | 59/30 | 4/4 (2) | 1 | −0.4 | 4.4 | 0.12 | 0.96 | 65 | 6.3 |

| RBD06 | 74/M | 127 | 0/0 | 63/0 | 4/5 (1) | 0 | 19.4 | 9.0 | 0.33 | 0.95 | 90 | 22.1 |

| RBD07 | 78/M | 111 | 0/0 | 7/11 | 4/5 (1) | 0 | 6.7 | 4.8 | 0.09 | 0.75 | 62 | 9.5 |

| RBD08 | 70/M | 336 | 6/0 | 19/26 | 1/2 (7) | 1 | 21.3 | 5.4 | 0.19 | 0.93 | 55 | 15.6 |

| RBD09 | 72/F | 40 | 33/0 | 100/44 | 1/2 (7) | 3 | 19.9 | 3.2 | 0.11 | 0.81 | 42 | −6.5 |

| RBD10 | 66/F | 63 | 6/0 | 63/11 | 1/2 (7) | 0 | 48.4 | 11.4 | 0.28 | 0.66 | 57 | 24.0 |

| RBD11† | 65/M | 443 | 11/0 | 85/59 | 1/2 (7) | 1 | 30.2 | 28.2 | 0.69 | 0.87 | 95 | 21.5 |

| RBD12† | 65/M | 46 | 100/0 | 100/59 | 1/2 (7) | 3 | 48.4 | 40.2 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 87 | 45.0 |

| RBD13 | 74/F | 41 | 11/0 | 4/4 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | 11.8 | 12.9 | 0.30 | 0.82 | 83 | 0.0 |

| RBD14† | 61/M | NA | 100/0 | 93/4 | 2/2 (6) | 1 | 37.1 | 30.7 | 0.96 | 1.16 | 70 | 12.8 |

| RBD15 | 66/M | 21 | 0/0 | 4/4 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | 5.5 | 1.0 | 0.03 | 0.95 | 33 | 0.0 |

| RBD16† | 60/M | 160 | 100/0 | 67/15 | 3/5 (2) | 1 | 56.4 | 39.6 | 0.78 | 0.97 | 70 | 75.0 |

| RBD17 | 63/F | 67 | 0/0 | 4/4 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.01 | 0.98 | 62 | 0.4 |

| RBD18 | 74/M | 2 | 0/0 | 19/33* | 2/2 (6) | 0 | 6.9 | 3.3 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 57 | −1.3 |

| RBD19 | 68/M | 11 | 0/0 | 7/4 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | 6.3 | 1.9 | 0.11 | 0.99 | 65 | −1.6 |

| RBD20 | 77/F | 21 | 0/0 | 30/4 | 5/5 (0) | 1 | 12.7 | 12.0 | 0.28 | 0.88 | 52 | 4.3 |

| RBD21 | 75/M | 46 | 0/0 | 4/4 | 4/5 (1) | 1 | 2.7 | 0.1 | −0.03 | 0.98 | 47 | 3.8 |

| RBD22 | 62/M | 27 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 5/5 (0) | 1 | 4.9 | −1.3 | 0.02 | 0.98 | 70 | −0.5 |

| RBD23 | 78/M | 40 | 100/22 | 81/4 | 0/3 (7) | 1 | 30.6 | 3.8 | 0.18 | 0.92 | 72 | 7.5 |

| RBD24† | 47/F | 68 | 6/0 | 52/0 | 5/5 (0) | 1 | 20.1 | −0.5 | 0.29 | 0.83 | 85 | 11.5 |

| RBD25 | 50/M | 59 | 0/0 | 15/4 | 4/5 (1) | 2 | 3.9 | 8.6 | 0.23 | 0.77 | 77 | 10.0 |

| RBD26 | 41/M | 63 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | −1.3 | −1.5 | −0.03 | 1.00 | 65 | 0.6 |

| RBD27 | 66/M | 55 | 6/0 | 0/0 | 2/5 (3) | 1 | −3.1 | −0.7 | 0.07 | 1.02 | 87 | 0.5 |

| RBD28 | 74/F | 105 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | 1.6 | −2.1 | −0.03 | 0.99 | 55 | 2.5 |

| RBD29 | 50/F | 81 | 0/0 | 67/11 | 3/3 (4) | 1 | 15.1 | 2.5 | 0.07 | 0.85 | 80 | 1.4 |

| RBD30 | 62/M | 105 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | 2.8 | 5.7 | 0.20 | 0.98 | 70 | −7.5 |

| RBD31 | 51/M | 60 | 0/0 | 4/0 | 4/5 (1) | 0 | 8.1 | 1.8 | 0.03 | 0.95 | 52 | 1.0 |

| RBD32† | 81/M | 32 | 100/17 | 67/37 | 1/2 (7) | 2 | 13.4 | 7.0 | 0.24 | 0.70 | 77 | 25.3 |

| RBD33 | 62/M | 72 | 100/0 | 100/41 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | 22.3 | 0.9 | 0.13 | 0.89 | 75 | 9.5 |

| RBD34† | 81/M | 74 | 0/0 | 26/4 | 4/5 (1) | 0 | 9.4 | 4.8 | 0.05 | 0.91 | 52 | −0.9 |

| RBD35 | 77/M | 314 | 0/0 | 30/19 | 2/5 (3) | 1 | 13.6 | 2.4 | 0.31 | 0.87 | 58 | 0.0 |

| RBD36 | 67/M | 32 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 5/5 (0) | 1 | 6.0 | 1.9 | 0.11 | 1.17 | 87 | 43.8 |

| RBD37† | 62/F | 43 | 61/0 | 89/37 | 0/2 (8) | 2 | 34.8 | −2.4 | 0.53 | 0.81 | 38 | 8.2 |

| RBD38 | 67/M | 41 | 0/0 | 7/11 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | 9.8 | 3.6 | 0.00 | 0.90 | 48 | 0.6 |

| RBD39 | 63/M | 60 | 0/0 | 4/0 | 2/5 (3) | 0 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 0.03 | 0.91 | 62 | 7.1 |

| RBD40 | 68/F | 74 | 0/0 | 15/7 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | 4.5 | −1.3 | −0.03 | 0.95 | 70 | 0.4 |

| RBD41 | 71/F | 88 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | 0.6 | 6.7 | −0.03 | 0.81 | 57 | 2.5 |

| RBD42 | 71/F | 59 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 0.06 | 1.06 | 73 | 3.3 |

| RBD43 | 72/M | 28 | 0/0 | 7/0 | 5/5 (0) | 2 | 4.3 | 3.4 | −0.01 | 0.95 | 65 | 0.0 |

| RBD44 | 61/M | 39 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 3/5 (2) | 2 | 5.8 | 2.4 | 0.08 | 1.04 | 57 | 0.1 |

| RBD45 | 54/F | 57 | 0/0 | 37/11 | 4/5 (1) | 2 | 13.4 | 1.1 | 0.20 | 0.90 | 45 | 8.3 |

| RBD46 | 89/M | 8 | 100/22 | 100/56 | 0/2 (8) | 2 | 40.9 | −7.25* | 0.05 | 0.81 | 65 | 16.9 |

| RBD47 | 68/M | 19 | 0/0 | 4/7 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | 10.6 | 0.6 | 0.03 | 0.97 | 62 | 0.6 |

| RBD48 | 78/F | 45 | 0/0 | 4/15* | 5/5 (0) | 0 | 24.6 | 8.4 | 0.30 | 0.92 | 48 | 25.3 |

| RBD49 | 76/F | 47 | 0/0 | 7/7 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | 10.4 | 3.1 | 0.09 | 0.97 | 65 | 2.5 |

| RBD50 | 78/F | NA | 0/0 | 0/0 | 5/5 (0) | 0 | −0.9 | −0.5 | −0.05 | 0.97 | 60 | 0.0 |

| TOTAL LEFT NEGLECT | 13 | 23 | 20 | 26 | 28 | 22 | 30 | – | – | – | ||

| TOTAL RIGHT NEGLECT | 0 | 2 | – | – | 0 | 1 | 0 | – | – | – | ||

| TOTAL NO NEGLECT | 37 | 25 | 30 | 24 | 22 | 27 | 20 | – | – | – | ||

2.2. Procedure

Testing was conducted at a table in a quiet private room, or screened-off at the bedside, with the experimenter sitting directly opposite the patient except where stated. All patients used the right hand for manual responding, although handedness was not formally assessed. The first testing block comprised an assessment of visual field deficits by confrontation, followed by five standard procedures for the diagnosis of neglect: the line crossing (i.e. cancellation) and star cancellation conventional sub-tests of the Behavioural Inattention Test (BIT: Wilson et al., 1987); a five-item scene copying task adapted from Gainotti et al. (1972); a drawing-from-memory task adapted from the BIT; and a ‘multiple’ line bisection task adapted from Schenkenberg et al. (1980). The operational definition of neglect for the present study was the finding of neglect on any of these five core tests, according to the criteria specified in the test descriptions below.

Following the first screening block, each patient was tested on a paper-and-pencil horizontal line bisection task administered according to the ‘endpoints weightings’ procedure of McIntosh et al. (2005). They were also tested on computerised versions of horizontal size-matching (after Milner and Harvey, 1995) and Bisiach's version of the landmark task (Bisiach et al., 1998), to assess horizontal length comparison. These additional tasks were administered according to the patient's level of concentration and motivation. Typically, either size-matching (in 30 cases) or line bisection (in 11 cases) was performed immediately after the screening block, with the other two tasks in a second session on a separate day; or the three tasks were administered in the second session (five cases). In two cases, where motivation was high, the patient performed all of the tests at a single session, and in two other cases, the tests were split across three sessions. An effort was always made to complete all tests within a minimum span of days, to obtain as static a snapshot of symptoms as possible. The median span was two days, with testing completed within four days in 47 cases, and in five, six and eight days in the remaining three cases.

The specific testing and scoring procedures were as follows:

2.3. Line and star cancellation tasks

These conventional sub-tests of the BIT involve, respectively, a structured cancellation array of randomly oriented lines with no distractors (after Albert, 1973), and a more complex cancellation array with small-star targets pseudo-randomly interspersed with non-target distractor items (large stars, words and letters) (Wilson et al., 1987). In both tasks, the A4 landscape sheet was placed directly in front of the patient, and the researcher explained the task, indicating the extent of the array and then crossing out two central targets by way of demonstration. The patient was asked to cancel the remaining targets, and to tell the researcher when they were finished, or to put the pen down. If the patient persisted in an unproductive pattern of searching, or ceased searching without indicating completion, the researcher gave a maximum of two prompts, asking if the patient could find any more targets. The third prompt would be to ask explicitly whether the patient was finished. The cut-offs for abnormal performance, taken from the BIT manual, were omission of two or more lines (from 36), and omission of three or more stars (from 54) (Wilson et al., 1987). As in prior studies (e.g. McIntosh et al., 2004; McIntosh et al., 2005), we additionally applied the criterion of Robertson and colleagues (1994), which requires at least 10% more omissions on one side than the other in order to diagnose lateralised neglect (left or right). This left-right difference criterion was used for diagnostic categorisation, but the summary score entered to further analyses was simply the total percentage of targets omitted for each task (see Discussion for consideration of alternative metrics of cancellation performance).

2.4. Copying task

A five-item scene adapted from Gainotti et al. (1972) was presented, in landscape orientation. The extent of the array was indicated and the patient was asked to copy the scene into the blank space below, and to tell the researcher when they were finished, or to put the pen down. If the patient stopped drawing, without indicating completion, the researcher gave one prompt to ask if the patient was finished. Performance was assessed in terms of the number of items copied and the number of attempted items copied with left-sided details missing. To produce a single summary score for further analyses, we followed Johannsen and Karnath (2004), scoring one for each object drawn with left sided details missing, and two for each item omitted from the left of the scene. This gave a possible left neglect score between zero and ten, and scores of two or above were taken to indicate left neglect for this task (cf. Johannsen and Karnath, 2004).

2.5. Drawing task

The patient was asked to draw three items from memory: “a large clock face, big enough to fit all the numbers on, with the time set to nine o’ clock”; “a flower-head, like a daisy”; and “a person; it can be a simple stick figure if you like”. One point was scored for each item drawn with left-sided details missing, and patients that were judged to show neglect for any figure were identified as having neglect for this task.

2.6. Multiple line bisection task

The ‘multiple’ line bisection task, adapted from Schenkenberg et al. (1980), presented 16 horizontal lines, varying from 2 to 26 cm in length (average 14 cm), at a variety of positions on an A4 landscape sheet. The patient was required to bisect every line, and any lines not spontaneously bisected were pointed out to the patient, so that all were completed. The summary score was the average bisection error, and neglect was indicated where this exceeded 7 mm (>10% of average line half-length; Schenkenberg et al., 1980).

2.7. Line bisection (endpoint weightings) task

The line bisection task used 32 horizontal line stimuli (3 mm thick), printed individually in black ink on white A4 paper in landscape orientation. There were eight repetitions of each of four unique lines, created by crossing two left endpoint positions (−40 and −80 mm from the horizontal midline of the page) with two right endpoint positions (+40 and +80 mm from the horizontal midline of the page), presented in a fixed-random order. Each sheet was placed directly in front of the patient, with the page aligned centrally with the body midline. Patients were required to mark the midpoint of the line with a pen held in the right hand, removing their hand from the table after each response, to discourage an invariant response position.

The raw dependent measure on each trial was the response position (P), coded with respect to the page midline. The weighting for each endpoint can then be defined as the mean change in P associated with a shift in that endpoint between its two locations, expressed as a proportion of the size of the endpoint shift (40 mm). In practice, to compute these values, P was regressed upon the left and right endpoint locations according to a linear model, with the coefficient for each endpoint giving the weighting for that endpoint. Thus:

Where L and R are the line endpoint positions, dPL and dPR are the endpoint weightings, and k is a regression constant. Two composite measures, endpoint weightings bias (EWB) and endpoint weightings sum (EWS), were then derived as follows:

In addition to this ‘endpoint weightings’ analysis, the classical measure of directional bisection error (DBE) with respect to the midpoint of the line was also calculated for each patient. Normal cut-offs for this task were available from a control sample of 30 older-adult participants (mean 71.3 years; SD 9.1), reported in Experiment 1 of McIntosh et al. (2005). Upper and lower limits of normality were set at 2.08 standard deviations around the control mean, defining two-tailed cut-offs for neglect using the modified t-criterion for small control samples (Crawford and Howell, 1998). The upper and lower cut-offs, for left and right neglect respectively, were: +3.5 and −4.5 mm for DBE; and +0.07 and −0.13 for EWB.

2.8. Size matching task

The size-matching task was performed on a laptop computer using custom software to present pairs of white outline rectangles against a black background. The rectangles were 10 mm high, centred vertically on the screen, and spaced equally around the horizontal midline, with a centre-to-centre separation of 56 or 111 mm (‘near’ and ‘far’ separation conditions respectively). The patient was informed that there would always be two rectangles present, which would never be exactly the same horizontal length. The task was to judge which was longer (or shorter) in horizontal length and to indicate the response by pointing to that rectangle with the right index finger. The experimenter sat alongside the patient, on the right, recording the patient's pointing responses using the arrow keys of the laptop.

There were two blocks of 30 trials, one requiring the patient to indicate the longer rectangle, and one the shorter, with the order of blocks alternated between patients. Each block included 15 trials at each separation condition, shuffled randomly, with five trials in which both rectangles were equal to the standard length (67 mm), five trials in which the left rectangle was shorter than the standard (by 3.3, 6.7, 10.0, 13.3 or 16.7 mm), and five trials in which the right rectangle was shorter (by 3.3, 6.7, 10.0, 13.3 or 16.7 mm). Thus, across two blocks, and across separation conditions, there were 20 trials in which the rectangles were of equal length, 20 trials in which the left was shorter, and 20 trials in which the right was shorter. The summary score was simply the percentage of responses in which the patient's response implied that the left rectangle was the shorter, with higher scores indicating greater underestimation of left extents. The size-matching task was included to investigate the relation between assessments of size and length perception and line bisection. It is not a diagnostic task for neglect, so diagnostic cut-offs were not defined.

2.9. Landmark task

The landmark task was performed using customized software, with the researcher sitting alongside the patient, on the right, to record the responses using the arrow keys of the laptop. The software implemented Bisiach's version of the landmark task (Bisiach et al., 1998), itself adapted from Milner et al. (1993). Bisiach and colleagues had two versions of the task, requiring verbal or manual responding, but we used verbal and manual responding together, to avoid any ambiguity. In each trial, a horizontal line, 180 mm long and 1 mm thick, was presented against a white background. Each line consisted of a red portion and a black portion. The patient was informed that there would always be a red part and a black part, which would never be exactly the same length. The task was to judge which portion was longer (or shorter) in horizontal length and to respond by naming the colour and pointing to that end of the line with the right index finger. The patient was encouraged to point to the very end of the line, to avoid confusion, and to try to ensure that the whole line had been seen.

There were two blocks of 54 trials, one requiring the patient to indicate the longer portion, and one the shorter, with the order of instructions alternated between patients. Each block included six trials in each of nine conditions, shuffled randomly, with the transection mark in the exact centre, or 5, 15, 30, or 60 mm to the left or right. For each transection position, half of the trials had the red portion on the left and half had the black portion on the left. The landmark task has been used previously to assess perceptual biases and response biases (Bisiach et al., 1998, Harvey and Olk, 2000, Milner et al., 1993, Toraldo et al., 2002). In the present context we were interested only in the assessment of perceptual bias. This was quantified using the method proposed by (Toraldo et al., 2004, Toraldo et al., 2010) to estimate the point of subjective equality (PSE) at which the patient perceives the two portions of the line as being equal in length. As for size-matching, the landmark task was included to investigate the relation between assessments of size and length perception and line bisection, so diagnostic cut-offs were not defined.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of neglect

Test scores for each patient are listed in Table 1. The summary counts at the foot of the table show that the different diagnostic methods classified between 13 and 30 patients as exhibiting left neglect (and between 0 and 2 as exhibiting right neglect). Our strategy of preferentially recruiting patients with clinical suspicion of neglect seems to have yielded a somewhat continuous spread of neglect severity. Considering the five standard diagnostic tests administered at the first session, 11 patients showed no neglect, whilst the numbers of patients with left neglect on one, two, three, four or five tests respectively were: 12, 7, 6, 4 and 10. This spread of severities provides an excellent basis for investigating patterns of shared variance between tests, although the biased selection strategy should be borne in mind when comparing with studies that have used unselected samples of right-brain damaged patients (e.g. Azouvi et al., 2002; Sperber and Karnath, 2016; Verdon et al., 2010), or conversely with studies in which the correlational analyses were restricted to patients with positive signs of neglect (e.g. Binder et al., 1992; Guariglia et al., 2014).

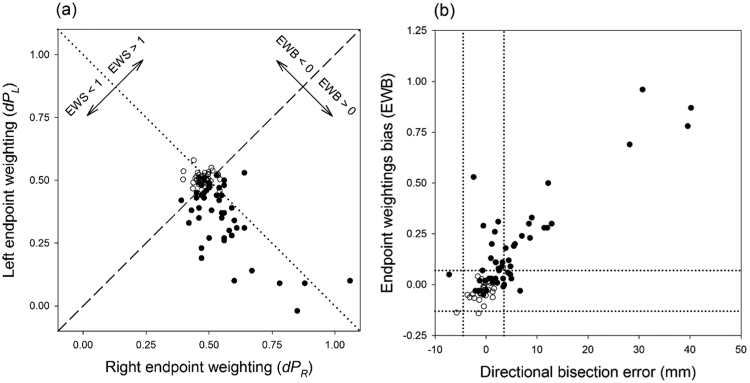

Direct comparisons of sensitivity across the different diagnostic measures are not necessarily appropriate, given that the cut-offs were based on different control samples and/or strategies, and in the absence of a gold standard measure. However, two patterns from prior literature were strongly replicated. First, star cancellation was more sensitive to bias than was line cancellation, as expected given the presence of distractor items, and a denser and less structured array (Halligan et al., 1989; Rapcsak et al., 1989). Twelve instances of left neglect (and two of right neglect) were identified by star cancellation but not by line cancellation, whereas only one patient (RBD13) qualified for left neglect on line cancellation but not on star cancellation. Second, the EWB measure of bias on the bisection task was more sensitive to right brain-damage than was the traditional index of DBE taken from the same task (McIntosh et al., 2005). Thirteen instances of left neglect were identified by EWB but not by DBE, whereas only five patients qualified for left neglect, and one qualified for right neglect, by DBE but not by EWB. The endpoints weightings analysis thus offers a metric of bisection behaviour that is more sensitive to pathological bias than is the classical measure of bisection error (see Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Experiment 1. (a) Scatterplot relating right and left endpoint weightings for 50 RBD patients (filled circles), and 30 healthy controls (open circles) (control data from McIntosh et al., 2005). The dashed diagonal represents the line on which the two endpoint weightings are equal, so that the endpoint weightings bias (EWB) equals zero. The dotted diagonal represents the line on which the endpoint weightings sum (EWS) equals one. (b) Scatterplot relating directional bisection error and endpoint weightings bias for participants in Fig. 2a. The dotted lines represent upper and lower cut-offs, for left and right neglect respectively, according to each measure (see Methods for details).

Fig. 2a illustrates the relationship between the left and right endpoint weightings, and how they co-determine the composite measures EWB and EWS. Compared to 30 healthy older controls (from McIntosh et al., 2005), RBD patients very often had a reduced weighting (< 0.5) for the left endpoint, and, in association with this, an increased weighting for the right endpoint. The negative relationship between endpoint weightings was strong but far from perfect (Spearman's ρ = −0.43 for this RBD cohort), so for a given difference between the weightings (EWB, or position with respect to the dotted diagonal), the sum of the two weightings can still vary (EWS, or position with respect to the dashed diagonal). The composite measures, EWB and EWS, are therefore statistically related (ρ = −0.36) yet meaningfully separable indices of performance, which we have suggested can be conceived of as the lateral attentional bias and the total attentional resource respectively. RBD patients tend to have EWB scores that are positive (rightward bias), and EWS scores that are lower than one (generalised inattention).

To focus on the key index of bias (EWB), Fig. 2b shows that, although the relationship with DBE is strong (ρ = 0.59), there are marked discrepancies between the measures. Some of the thirteen cases in which DBE falls within normal limits but EWB indicates left neglect seem frankly anomalous, because the discrepancy between measures is pronounced, and there is one patient with a sufficiently negative bisection error to indicate right neglect, who falls within normal limits on the EWB index. There are fewer reverse discrepancies, in which neglect is indicated by bisection error but not by EWB, and none that are pronounced.

3.2. Inter-correlations amongst measures of neglect

Before considering the inter-correlations amongst measures, we should consider the raw distributions of scores. For the majority, the distribution was skewed and/or included extreme values, as is quite typical of clinical screening data. Shapiro-Wilks tests indicated significant departures from normality (W ≥ 0.87, p < .001) for all measures except for EWS and percentage ‘left-is-smaller’ judgements in size-matching. These departures from normality create potential problems for correlational analyses. The use of Pearson's correlations is almost universal in prior literature on this topic, but Pearson's r may be distorted by extreme values and skew, and so the strength of relationship estimated using this method may not be straightforwardly interpretable (this applies to prior studies as well as to the present dataset). We will report Pearson's r in our main analysis, for compatibility with prior work, but we additionally report a non-parametric analysis in Appendix A, with each variable converted to ranks (i.e. Spearman's correlations), to confirm that the main patterns are robust (Table A1 shows the complete set of Pearson's and Spearman's coefficients).

The upper section of Table 2 reports Pearson's correlations amongst the initial block of diagnostic tests of neglect. The relationships were generally strong (r close to or exceeding 0.5), slightly less so for drawing, perhaps because of the restricted scoring range for this test (0−3) and its dependence on qualitative judgements of symmetry. A strong correlation was observed between star cancellation and multiple line bisection (0.71), which was unexpected, as prior literature has emphasised a poor relationship between cancellation and bisection in neglect. This particular bisection task was atypical in that 16 lines were presented on a single sheet, where previous studies have almost always used lines presented individually (though Halligan et al., 1989, presented three lines on a single sheet). The possible importance of this distinction will be considered in Discussion; but the present focus will be on the endpoint weightings format of the bisection task, which uses the standard approach of presenting each line individually.

Table 2.

The upper section shows Pearson's inter-correlations for the initial block of diagnostic tests. The middle section shows that the classical measure of directional bisection error (DBE), from the bisection of individual lines, correlated only modestly with other diagnostic procedures (cancellation, copying and drawing), but that the correlations were significantly stronger if EWB from an endpoint weightings analysis was used to index bias in the bisection task. The lower section shows that the second composite measure from the endpoint weightings analysis, EWS, also had some degree of correlation with diagnostic measures of neglect. The bottom row shows the multiple correlation obtained using a linear combination of the two endpoint weightings measures (EWB + EWS). ltalic values indicate non-significant correlations, correcting for false discovery rate within the full correlation matrix for ten dependent measures (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995).

| LINES | |||||

| 0.75 | STARS | ||||

| 0.62 | 0.74 | COPY | |||

| 0.41 | 0.56 | 0.50 | DRAW | ||

| 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.32 | MULTI-BISECT |

| DBE | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.63 |

| EWB | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.35 | 0.77 |

| difference | t = 2.26 p < 0.05 |

t = 3.18 p < 0.005 |

t = 3.00 p < 0.005 |

t = 2.04 p < 0.05 |

t = 2.74 p < 0.01 |

| EWS | −0.28 | −0.48 | −0.43 | −0.25 | −0.34 |

| EWB + EWS | 0.58 | 0.71 | 0.62 | 0.41 | 0.81 |

The middle section of Table 2 concerns alternative measures of bias for the endpoint weightings bisection task. DBE was relatively poorly related to other diagnostic measures of neglect. By contrast, the EWB measure obtained from an alternative analysis of the very same bisection responses was better related to the other core measures across the board. Formal tests on the difference in the strength of correlation were performed by Steiger's (1980) method, as implemented in javascript by Lee and Preacher (2013). The outcomes are reported in the third row of the middle section of Table 2, confirming that the advantage for EWB was significant in each case.

The lower section of Table 2 shows that some additional predictive power was provided by the second composite measure of the endpoint weightings analysis: EWS. EWS was not strongly inter-related with EWB (r = − 0.14), so the correlations exceeding this level in the first row of the lower section suggest that EWS had some unique relationship with the other core measures. The multiple correlation coefficients in the bottom row confirm this. These coefficients represent the total correlation between the best linear combination of the two endpoint weightings measures (EWB + EWS) and each other diagnostic test (i.e. the Pearson correlation between the predicted and actual values for that test in a linear regression with EWB and EWS as predictors, including an intercept term). EWS had its strongest relationship with star cancellation, bringing the multiple correlation with star cancellation up to 0.71; the equivalent multiple correlation for the analysis of ranked data was 0.73, as reported in the bottom row of Table A1.

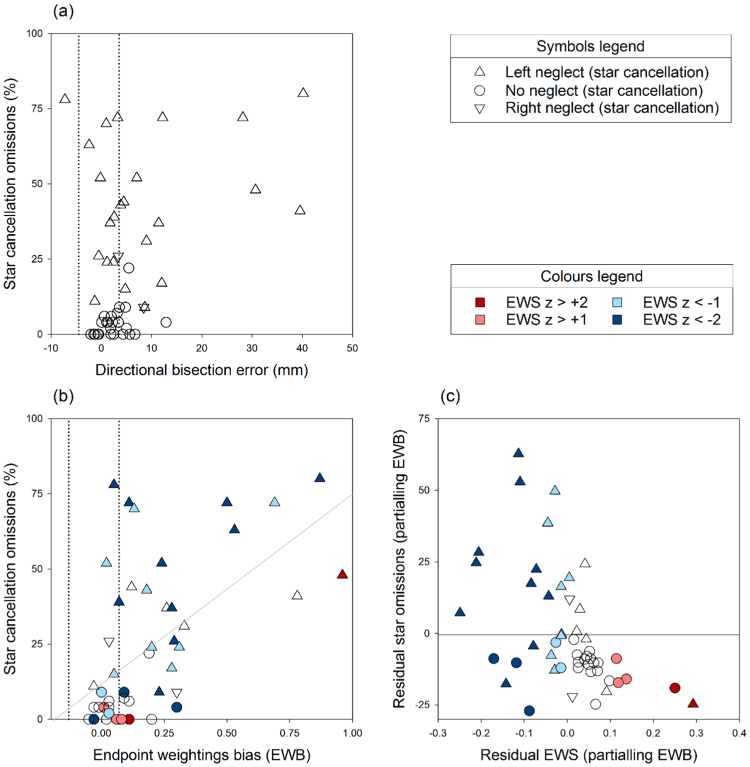

DBE therefore correlates rather poorly with star cancellation, but EWB does much better, and EWS captures further variance in cancellation omissions. Between them, the two indices of bisection behaviour that emerge from an endpoint weightings analysis correlate as strongly with star cancellation as does any other core test of neglect. The scattergrams in Fig. 3 depict these findings.

Fig. 3.

Scattergrams showing the relationship of star cancellation omissions with DBE (top), and with EWB and EWS (bottom). Dotted lines show cut-offs for right and left neglect on DBE and EWB measures, and symbol shape indicates neglect status on star cancellation. Symbol colour indicates EWS performance in terms of z-score relative to controls, with negative (blue) scores representing low EWS and positive (red) scores high EWS (z scores are not distinguished below −2, although they ranged as low as −5.8). Panel (a) shows that the relationship of star cancellation omissions with DBE is relatively poor (r = 0.38). Panel (b) shows that the relationship with EWB is much stronger (r = 0.58), though imperfect. The grey line is the best fitting straight line. Patients above this fit line, who omit more targets than predicted from their EWB score, tend to have low EWS (blue symbols). Conversely, patients with high EWS (red symbols) tend to be below the fit line, omitting fewer targets than expected. This partial relationship is depicted in panel (c), which plots residual EWS against residual omissions (r = −0.49), after the influence of EWB has been removed. The multiple correlation of EWB and EWS with star omissions is r = 0.71 (see Table 2). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.3. Principal Components Analysis (PCA)

The emerging consensus that line bisection error does not reflect core aspects of neglect has been underpinned by PCA approaches, which attempt to identify the underlying components of variation in neglect behaviour. Studies using PCA have sometimes (though not always) concluded that line bisection error is distinct from what is measured by other core tests (Azouvi et al., 2002, McGlinchey-Berroth et al., 1996, Verdon et al., 2010). Most recently, Sperber and Karnath (2016) reported that line bisection constituted a component that was separable from cancellation (letter and bells cancellation tasks) and multi-item copying.

PCA results are not necessarily straightforward to interpret. The structure found will depend heavily upon the range of tests considered; and the number of components in the solution will depend upon the criteria for extraction. Sperber and Karnath (2016) found that line bisection constituted a separable component, but this was in the context of an unusually low threshold for extraction of components (Eigenvalue > 0.7), where a more conventional threshold (Eigenvalue > 1, as in the popular criterion of Kaiser, 1960) would have yielded a single-component solution, with line bisection loading relatively weakly onto that one component. In such circumstances, PCA may not provide much more insight than the correlation matrix itself, which shows already that line bisection error correlates relatively poorly with other core tests.

Nonetheless, since prior studies have relied on this approach, we attempted to test for a component structure amongst our tests of neglect. To maximise the chances of a reliable solution, we included no more than five variables (allowing 10 observations per variable in our sample of 50 patients). We excluded, on theoretical grounds, the line cancellation task, which is essentially a less sensitive version of star cancellation, and the multiple line bisection task, because our interest is in the bisection of individual lines. To represent line bisection, we entered either the traditional measure of DBE (in the first analysis: PCA_A) or the two composite measures (EWB and EWS) derived from the endpoint weightings analysis (in the second analysis: PCA_B). To follow Sperber and Karnath (2016), we used a low extraction threshold (Eigenvalue > 0.7), with varimax rotation to differentiate the pattern of loadings. These analyses, conducted using SPSS (v22), are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Loadings from two separate PCA analyses, after varimax rotation. The first analysis (PCA_A) represented line bisection using the traditional measure of DBE. The second analysis (PCA_B) substituted the endpoint weightings indices, EWB and EWS. The major factor loading for each variable is shown in bold.

|

PCA_A with directional bisection error |

PCA_B with endpoint weightings indices |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component 1 | Component 2 | Component 1 | Component 2 | |

| % variance | 60.0 | 20.9 | 57.6 | 17.4 |

| Eigenvalue | 2.4 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 0.9 |

| STARS | 0.85 | 0.31 | 0.80 | 0.44 |

| COPY | 0.84 | 0.23 | 0.74 | 0.44 |

| DRAW | 0.83 | −0.02 | 0.68 | 0.23 |

| DBE | 0.15 | 0.97 | – | – |

| EWB | – | – | 0.86 | −0.12 |

| EWS | – | – | −0.13 | −0.95 |

The first analysis (PCA_A) provides a near-replication of Sperber and Karnath's result, with line bisection (DBE) loading onto its own component, largely separate from the other diagnostic measures. The second analysis (PCA_B), which uses the endpoint weightings indices, finds that the index of bias (EWB) loads heavily on the first component along with the other diagnostic tests, whilst EWS dominates the second factor with modest loadings from star cancellation and copying. These patterns are just as expected from the correlations in the previous section: EWB is much more closely related to other core measures of neglect than is DBE, and EWS captures some additional aspect of impairment.

3.4. Relation to size and length perception

Line bisection is generally assumed to assess the relative judgement of horizontal extents to the left and right. To investigate the validity of this idea in patients with neglect, we included two tests explicitly requiring the comparison of horizontal extents: size-matching and the landmark task. We assessed the correlations between these latter two tests and diagnostic tests of neglect, including line bisection. For these analyses, the Pearson's correlation coefficients were quite strongly distorted by the presence of extreme values (see Table A1), so Spearman correlations are reported here (Table 4).

Table 4.

Spearman's correlations between size-matching and landmark performance, and tests of neglect. Size-matching and landmark tasks inter-correlate significantly, but not strongly, at ρ = 0.33 (p < 0.05). Italic values indicate non-significant correlations, correcting for false discovery rate within the full correlation matrix for ten dependent measures (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995).

| LINES | STARS | COPY | DRAW | MULTI-BISECT | DBE | EWB | EWS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIZE-MATCH | 0.22 | 0.11 | −0.02 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.08 |

| LANDMARK | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.49 | −0.19 |

Size-matching performance did not correlate significantly with any measure of neglect. It did correlate significantly with landmark performance (ρ = 0.33, p < 0.05), but this was an unimpressive relationship for two tests designed to tap the same general ability. On this basis, and although size-matching may be biased in neglect (Table 1; see also Milner and Harvey, 1995), it seems that this test does not relate informatively to other diagnostic tests. The landmark test related only slightly better to measures of neglect. The strongest relationships in Table 4 are between landmark performance and metrics of line bisection, but notably not DBE for individual lines, the measure that should theoretically be most closely equivalent to the landmark test's point of subjective equality. The main conclusion is that there is little evidence that DBE for individual line bisection is related strongly to size or length perception or, indeed, that the perception of horizontal extent is an ability that is assessed with much reliability in patients with neglect.

3.5. Relation to visual field deficits

Previous studies have found ipsilesional bisection errors to be more pronounced for patients in whom neglect co-occurs with visual field deficits (Daini et al., 2002, Doricchi and Angelelli, 1999, Sperber and Karnath, 2016). However, the differential diagnosis of hemianopia and neglect is not straightforward, and dense neglect may be mistaken for hemianopia when confrontation testing is used (Kerkhoff, 2001). Testing the specific contribution of hemianopia ideally requires specialised assessments by perimetric and electrophysiological methods (e.g. Daini et al., 2002; Doricchi and Angelelli, 1999). This caveat should be borne in mind when considering the contribution of visual field deficits in the present cohort, in whom visual fields were assessed by confrontation only.

Nine patients were judged to have visual field deficits by this method. Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon tests found that, as a group, these nine patients showed significantly more neglect than those judged to have full visual fields, for line cancellation (U = 52.5, p < 0.005), star cancellation (U = 45, p < 0.005), copying (U = 73.5, p < 0.005), drawing (U = 100.5, p < 0.05), multiple line bisection (U = 43, p < 0.005), and DBE for individually-presented lines (U = 92.5, p < 0.05). But the most dramatic difference was for the endpoint weightings index of bias, EWB (U = 34.5, p < 0.005), with the six most extreme scores (EWB ≥ 0.50) all attributed to patients with visual field deficits. By contrast, visual field deficits were less predictive of reduced EWS (U = 111, p = 0.06), or increased perceptual bias for size-matching (U = 151.5, p = 0.4) or landmark tasks (U = 107, p = 0.052). The data suggest that visual field deficits, when combined with neglect, may severely limit the ability to process both ends of the line, forcing a reliance on the right endpoint position. Our cohort did not include any patients with visual field deficits without neglect, but such patients would be of interest for future studies using the endpoint weightings method. It could be informative to track performance longitudinally in such patients, given evidence that hemianopia may induce ipsilesional bisection errors in the acute phase (Sperber and Karnath, 2016), but contralesional errors in the chronic phase, due to neural reorganisation or compensatory scanning strategies (Barton and Black, 1998, Barton et al., 1998, Sperber and Karnath, 2016).

4. Discussion

The present data reinforce the consensus that the mean directional error of line bisection correlates relatively poorly with target cancellation in neglect (Azouvi et al., 2002, Binder et al., 1992, Ferber and Karnath, 2001, Guariglia et al., 2014, McGlinchey-Berroth et al., 1996, Sperber and Karnath, 2016, Verdon et al., 2010). Furthermore, using similar criteria for the extraction of principal components of variance across measures, we replicated Sperber and Karnath's (2016) recent finding that bisection error loads onto a separate component from cancellation and other core tests. Our results therefore support the idea that directional bisection error fails to capture the essence of the neglect syndrome. However, our analysis shows that this is not a limitation of the line bisection task per se, but of the dependent measure classically taken from it. When an endpoint weightings bias (EWB) was extracted from line bisection data by varying the positions of the left and right endpoints of the lines independently across trials, it proved to be a much more sensitive and valid measure. EWB loaded heavily, with other core tests, onto the principal component of neglect behaviour. This result is particularly striking given that the endpoints bisection task was usually administered on a different day from the set of core tests.

If an endpoint weighting is taken to index attentional allocation to that end of the line, then EWB represents the lateral attentional bias, and the endpoint weightings sum (EWS) represents the total attention allocated (McIntosh, 2017; McIntosh et al., 2005). Previous research has established that non-lateralised deficits of attention that are separable from the core bias of neglect nonetheless often co-occur with it, and strongly colour the expression of neglect symptoms in the real world, and in complex tests such as target cancellation (Chatterjee et al., 1992, Husain and Rorden, 2003, Kaplan et al., 1991, Rapcsak et al., 1989, Robertson, 1993). Consistent with this, we found that the lateral bias of neglect (EWB) was moderately associated with a reduction in the total attention resource (EWS), and that variation in EWS captured some variance in the other core tests (particularly star cancellation and scene copying), over and above that accounted for by EWB. In short, we found that bisection behaviour contains sufficient information to predict cancellation (and scene copying) performance reliably, but that an endpoint weightings analysis was needed to reveal this information.

4.1. Relation to cancellation

The multiple correlation of EWB and EWS with star cancellation was strong (r = 0.71), and on a par with the prediction offered by any other core test. The main prediction of cancellation omissions is provided by lateral bias (EWB), but the total resource (EWS) helps to explain why some (less attentive) patients tend to make extra omissions, whilst other (more attentive) patients do better than the severity of their bias would predict (Fig. 3, panels b and c). This co-determination is what we would expect if cancellations are limited by an overall reduction in attentional resource as well as by lateral bias, and if EWB and EWS effectively separate these two constructs. Moreover, given that cancellation omissions in right brain-damaged patients may additionally be influenced by spatial working memory deficits, the multiple correlation observed may be as high as could reasonably be expected without an additional assessment of spatial memory (Husain et al., 2001, Parton et al., 2006, Wojciulik, 2004, Wojciulik et al., 2001).

The influence of global inattention on cancellation omissions has led to the suggestion that neglect on such tasks would be better indexed by a more purely spatial measure of behaviour. Rorden and Karnath, 2010, Binder et al., 1992 suggested that one suitable measure is simply the mean horizontal location of targets cancelled: the Centre of Cancellation (CoC) (for a recent similar approach see Toraldo et al., 2017). This spatial index reflects the distribution of cancellations, and is in principle independent of their overall number, such that an inattentive patient with omissions spread evenly across the sheet would not be misclassified with neglect. If CoC is more valid than the standard omissions score, because it filters out effects of non-lateralised impairments, then we might expect it to relate less strongly to EWS (and, if anything, more strongly to EWB). Unfortunately, a full reanalysis of cancellation behaviour in terms of CoC is not possible for the present study, because the original cancellation sheets are no longer available for all patients, and CoC cannot be computed from the recorded summary scores. However, the original sheets were still available for 23 of the 50 patients, so CoC scores were calculated for the cancellation tasks for this sub-sample, using the free software provided by Rorden and Karnath (2010)2 The correlation between CoC and percentage omissions was found in this sub-sample to be very high (r =1.0 for line cancellation, and 0.95 for star cancellation), suggesting that these measures, though conceptually distinct, measure substantially the same thing. The choice between them is therefore unlikely to matter critically to the present findings, as the full pattern of correlations for this sub-sample confirms (Table A2, Appendix A).

Some authors have proposed that cancellation tasks should be regarded as the most valid tests of neglect, because they mimic the real-world clinical picture, in which the patient's spontaneous behaviour deviates rightward amongst competing alternative stimuli (Ferber and Karnath, 2001). There is much to recommend this viewpoint, and cancellation tasks certainly provide simple and rapid bedside measures of visual search in cluttered environments. However, the most sensitive cancellation tasks, recommended for diagnosis, are those that make high demands on focused selective attention by having unstructured arrays and/or distractor items (e.g. Halligan et al., 1989; Rapcsak et al., 1989), or that stretch spatial working memory by being administered in a format in which cancellations leave no visible trace (Wojciulik, 2004). The heightened sensitivity of such procedures comes from taxing spatially-non-lateralised functions to exacerbate any spatial asymmetry. Whilst this is an excellent strategy to expose and magnify neglect, the very same complexity would arguably make cancellation tasks less well suited to teasing apart the underlying neuropsychological impairments.

4.2. Relation to multiple bisection

The average directional error in our multiple line bisection task (16 lines on a single page) correlated highly with other core tests of neglect, including star cancellation (r = 0.71, ρ = 0.73), in contrast to bisection error for lines presented individually (r = 0.38, ρ = 0.28). This difference between multiple and individual modes of presentation was unexpected and would benefit from replication. Nonetheless, the effect was strong, and so it is worth speculating on its source. One explanation could be that a higher correlation emerged for multiple bisection because this was performed in the same block as the other core tests, whereas the bisection of individual lines was often performed on a different day. This explanation seems unlikely, however, because the differences are so great, and because the high correlations of multiple line bisection with other core tests contrast with the modest correlations found for standard line bisection in prior studies (Binder et al., 1992, Ferber and Karnath, 2001, Guariglia et al., 2014, Sperber and Karnath, 2016).

Alternatively, the main difference between the multiple line bisection task and the standard single-line format is that a cluttered visual array was presented, as opposed to a sparse sheet with a single line. As noted in the context of cancellation, a cluttered array increases stimulus competition and makes greater demands on focused selective attention (e.g. Halligan et al., 1989; Rapcsak et al., 1989). Such demands exacerbate the lateral bias of attention, leading to more rightward responding. The correlations in Table 2 (and Table 1A) show that rightward errors in multiple bisection were more strongly related to star cancellation omissions than to bisection errors for individually-presented lines. Neglect bisection errors may thus depend less upon the task instruction (to bisect a horizontal line) than upon the density of the visual display.

4.3. Relation to length perception

If bisection error is more affected by the density of the display than the nature of the task, and if the modulation of response position across different lines is more informative than the deviation from the true midpoint, then what does this imply for the widespread assumption that this task demonstrates faulty length perception? In the domain of spatial neglect, it has been long suggested that such patients might be incapable of making meaningful midpoint judgements (Kinsbourne, 1993, Koyama et al., 1997, McIntosh et al., 2005a), and the study of patient's eye movements tend to support this view (Ishiai et al., 1989, Ishiai et al., 2001, Ishiai et al., 2006, 1992; see McIntosh, 2006 for a summary). Thus, however natural it may be to assume that line bisection simply assesses length perception, it is an empirical question as to whether the data support this assumption. One way to approach this question is to ask whether other tests designed to assess length perception converge on similar results. A positive answer is initially suggested by the fact that neglect groups tend to bisect lines rightward, and also tend to require leftward line portions or shapes to be longer than those on the right before they judge them to be equal (Dijkerman et al., 2003, Harvey et al., 1995b, Milner and Harvey, 1995, Milner et al., 1993). These group-level results are consistent with a systematic underestimation of leftward extents, which can be revealed by a number of different tests tapping a common function.

Surprisingly, however, there have been no attempts to drill down below the group level, to confirm that bisection errors correspond across patients with these other measures of perceptual estimation. To our knowledge, only one study has reported line bisection and landmark data for a large cohort of relevant patients. Bisiach et al. (1998) tested 121 patients with left neglect on the bisection of five 180 mm lines, and on two versions of the landmark task (with verbal or manual responding) using lines of equivalent length. Although not a focus for that paper, the correlation of bisection error with perceptual bias on the landmark tasks was surprisingly weak (r = 0.34 and 0.31 for verbal and manual versions respectively). The present study likewise observed a rather poor, non-significant, relationship between (single) line bisection error and landmark bias (ρ = 0.29). The superficially similar size-matching task related slightly better than this to landmark judgements (ρ = 0.40), but it showed no significant correspondence with bisection error or indeed with any other measure of neglect. Therefore, despite a priori plausibility, there is little empirical evidence that line bisection error in neglect directly indexes the perception of horizontal length, or even that this ability can be reliably assessed in neglect patients at all.

4.4. Anatomical correlations

The present study is behaviourally-targeted, and the clinical brain imaging was unfortunately insufficient to support any neuroanatomical analysis. Yet our findings may have important implications for efforts to pin down the anatomical basis of neglect, because the anatomical counterparts revealed in such studies can only be as valid as the behavioural constructs that define them. There has been a longstanding debate as to whether the right angular gyrus of the inferior parietal lobe (Mort et al., 2003, Mort et al., 2004), or the superior temporal gyrus (Karnath et al., 2001, Karnath et al., 2004), should be regarded as the critical cortical lesion for neglect. In this Battle of the Gyri, line bisection may have played a key role, since the study that identified the inferior parietal locus used line bisection error in addition to cancellation performance as a diagnostic criterion (Mort et al., 2003), and line bisection error has itself been associated with more posterior brain lesions than cancellation measures of neglect (Binder et al., 1992, Rorden et al., 2006).

Consistent with a parietal focus for line bisection errors, a principal components approach to lesion-symptom mapping identified this task with a “perceptive/visuo-spatial” component of neglect, and a critical lesion in the inferior parietal lobe (Verdon et al., 2010). However, rather than identifying target cancellation with temporal lobe lesions, Verdon and colleagues identified an “object-based” component with the temporal lobe, whilst target cancellation loaded onto a separate “exploratory/visuo-motor” component with a critical lesion in the dorsolateral prefrontal lobe. The authors suggested that this association could reflect the importance of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for the executive control required to resist distraction from non-target or previously-visited items during cancellation. Indeed, as already discussed, the apparent sensitivity of cancellation tasks to neglect may partly reflect the complex demands of these tasks, which require selective attention, sustained attention, and even spatial working memory. If so, then the anatomical conclusions regarding neglect, as diagnosed by cancellation tasks (Karnath et al., 2001, Karnath et al., 2004), may be correspondingly biased by interacting impairments, even if a purely spatial index of cancellation behaviour is used. The endpoints weightings analysis of line bisection leads to separable indices of lateral attention bias (EWB), and of overall attentional resource (EWS), which cancellation does not provide. If our ideas stand up to future empirical testing and theoretical scrutiny, it may be of considerable interest to study the anatomical counterparts of EWB and EWS themselves.

5. Conclusion

Line bisection has long been an important clinical and experimental task for the study of neglect, but it now appears that directional bisection error relates only weakly to core measures of neglect, and to tests of horizontal length perception. We wish to argue, however, that the present findings can rescue line bisection from being consigned prematurely to the scrap heap of neuropsychology. Our endpoint weightings analysis provides an assumption-free measure of the influence that each endpoint has on the bisection response. Yet despite this atheoretical starting point, the endpoint weightings may be readily identified as measures of the extent and spatial distribution of attention allocated. The difference between the two weightings (EWB) is more sensitive to right brain damage than is directional bisection error, and it relates more strongly to cancellation and copying measures. Additional variation in cancellation and copying is captured by the sum of the two weightings (EWS), providing a combined predictive power that is on a par with the other core tests of neglect. Our contention is that, following our analysis, no major anomalies of bisection performance remain.

We suggest then that the line bisection task can retain a central role in the study of neglect, since it does tap into the core bias of neglect, although the traditional measure gives only a noisy and imperfect readout of this bias. By accident rather than by design, a sparse sheet with a single line, with two endpoints requiring attention, may be close to an ideal stimulus for measuring attentional asymmetry; but the twist is that we need to focus on the sensitivity to changes in either endpoint, rather than on the misleading metric of bisection error. This requires the administration of an extended series of lines (32 in the present study), but the quality of information gained may be well worth the investment. If the proposed theoretical status of EWB and EWS as separable measures of lateralised and non-lateralised aspects of attention can be substantiated and developed, line bisection could be an extremely useful task for the future study of neglect, easily administered in clinical settings, yet with the power to distinguish component symptoms that are confounded in patients’ responses to more complex stimulus arrays.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Tim Cassidy and Martin Dennis for facilitating access to patients in their care, and to Lara Pattison for assistance with data collection. This work was supported by an MRC component grant G0000680 to ADM & RDM, and MRC Cooperative grant G0000003 to ADM. The processed data and the basic endpoints stimuli for this study are uploaded as supplementary files. A digital version of the 'endpoint weightings' bisection task, suitable for touchscreens, can be found under RDM’s account at the Open Science Framework 〈https://osf.io/exps2/〉.

Footnotes

McIntosh et al. (2005) noted, however, that EWB is numerically equal to (twice) the slope of the function relating directional bisection error to line length in the classical task analysis, and EWS is equal to (one plus) the slope of the function relating bisection error to spatial position. Therefore, EWB might be able to be estimated retrospectively for datasets where line length has been varied systematically, and EWS where the position of the line on the sheet has been varied.

Available at Prof. Chris Rorden's academic webpages: http://www.mccauslandcenter.sc.edu/crnl/tools/cancel.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.09.014. A digital version of the 'endpoint weightings' bisection task, suitable for touchscreens, can be found under RDM’s account at the Open Science Framework 〈https://osf.io/exps2/〉.

Appendix A

see Appendix Table A1, Table A2

Table A1.

Correlation matrix for all measures for full cohort (n=50), additionally showing the multiple correlation of EWB + EWS with other measures (final row/column). Coefficients above the diagonal are Pearson’s r (untransformed data), and coefficients below the diagonal are Spearman’s ρ (ranked data). To control for the false discovery rate across all pairings of ten variables, correlations weaker than 0.3 (positive or negative) are classed as non-significant, and are reported in italic (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995).

|

r ρ |

LINES | STARS | COPY | DRAW | DBE_MULTI | DBE | EWB | EWS | SIZE-MATCH | LANDMARK | EWB + EWS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LINES | 0.75 | 0.62 | 0.41 | 0.68 | 0.39 | 0.54 | −0.28 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.58 | |

| STARS | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.38 | 0.58 | −0.47 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.71 | |

| COPY | 0.63 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.65 | 0.30 | 0.50 | −0.43 | −0.02 | 0.15 | 0.62 | |

| DRAW | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.32 | 0.20 | 0.35 | −0.25 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.41 | |

| DBE_MULTI | 0.58 | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.28 | 0.63 | 0.77 | −0.34 | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.81 | |

| DBE | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.85 | −0.07 | 0.27 | 0.59 | 0.85 | |

| EWB | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.74 | 0.59 | −0.14 | 0.23 | 0.52 | ||

| EWS | −0.40 | −0.61 | −0.44 | −0.29 | −0.45 | −0.30 | −0.36 | 0.13 | 0.05 | ||

| SIZE-MATCH | 0.26 | 0.11 | −0.02 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.40 | 0.28 | |

| LANDMARK | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.49 | −0.19 | 0.33 | 0.53 | |

| EWB + EWS | 0.60 | 0.73 | 0.57 | 0.40 | 0.76 | 0.60 | 0.32 | 0.49 |

Table A2.

Correlation matrix for neglect tests for sub-sample for whom a Centre of Cancellation (CoC) measure could be computed for the line and star cancellation. Coefficients above the diagonal are Pearson’s r (untransformed data), and coefficients below the diagonal are Spearman’s ρ (ranked data). To control for the false discovery rate, correlations weaker than 0.44 (positive or negative) are classed as non-significant, and are reported in italic (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). The main patterns of the full cohort are preserved in this sub-sample, regardless of which measure of cancellation performance is used. Specifically, DBE for individual lines correlates poorly with cancellation and other core measures of neglect, but EWB correlates much better, and EWS captures some additional variance in cancellation and copying performance. Note that the CoC scores are included, along with the other dependent measures, in the data spreadsheet that accompanies this study.

|

r ρ |

LINES (CoC) | LINES | STARS (CoC) | STARS | COPY | DRAW | DBE_MULTI | DBE | EWB | EWS | EWB + EWS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LINES (CoC) | 1.0 | 0.74 | 0.7 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.46 | −0.44 | 0.54 | |

| LINES | 0.99 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 0.4 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.48 | −0.46 | 0.56 | |

| STARS (CoC) | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.95 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.41 | 0.57 | −0.42 | 0.61 | |

| STARS | 0.8 | 0.78 | 0.95 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.45 | 0.63 | −0.47 | 0.68 | |

| COPY | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 0.43 | 0.63 | −0.50 | 0.69 | |

| DRAW | 0.47 | 0.5 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.41 | −0.23 | 0.42 | |

| DBE_MULTI | 0.62 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.16 | 0.61 | 0.79 | −0.54 | 0.83 | |

| DBE | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.81 | −0.31 | 0.81 | |

| EWB | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.30 | 0.80 | 0.58 | −0.39 | ||

| EWS | −0.5 | −0.47 | −0.48 | −0.55 | −0.51 | −0.29 | −0.57 | −0.49 | −0.51 | ||

| EWB + EWS | 0.62 | 0.6 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.34 | 0.83 | 0.62 |

Appendix C. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- Albert M.L. A simple test of visual neglect. Neurology. 1973;23(6) doi: 10.1212/wnl.23.6.658. (658–658) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axenfeld M. Hemianopische Gesichtsfeldtstörungen nach Schädelschüssen. Klin. Mon. Augenheilkd. 1915;55:126–143. [Google Scholar]

- Azouvi P., Samuel C., Louis-Dreyfus A., Bernati T., Bartolomeo P., Beis J.-M., Rousseaux M. Sensitivity of clinical and behavioural tests of spatial neglect after right hemisphere stroke. J. Neurol., Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2002;73(2):160–166. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.2.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton J.J., Black S.E. Line bisection in hemianopia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1998;64:660–662. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.64.5.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton J.J.S., Behrmann M., Black S. Ocular search during line bisection. The effects of hemi-neglect and hemianopia. Brain. 1998;121(6):1117–1131. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.6.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]