Abstract

Healthy, term, breastfed infants usually have adequate iron stores that, together with the small amount of iron that is contributed by breast milk, make them iron sufficient until ≥6 mo of age. The appropriate concentration of iron in infant formula to achieve iron sufficiency is more controversial. Infants who are fed formula with varying concentrations of iron generally achieve sufficiency with iron concentrations of 2 mg/L (i.e., with iron status that is similar to that of breastfed infants at 6 mo of age). Regardless of the feeding choice, infants’ capacity to regulate iron homeostasis is important but less well understood than the regulation of iron absorption in adults, which is inverse to iron status and strongly upregulated or downregulated. Infants who were given daily iron drops compared with a placebo from 4 to 6 mo of age had similar increases in hemoglobin concentrations. In addition, isotope studies have shown no difference in iron absorption between infants with high or low hemoglobin concentrations at 6 mo of age. Together, these findings suggest a lack of homeostatic regulation of iron homeostasis in young infants. However, at 9 mo of age, homeostatic regulatory capacity has developed although, to our knowledge, its extent is not known. Studies in suckling rat pups showed similar results with no capacity to regulate iron homeostasis at 10 d of age when fully nursing, but such capacity occurred at 20 d of age when pups were partially weaned. The major iron transporters in the small intestine divalent metal-ion transporter 1 (DMT1) and ferroportin were not affected by pup iron status at 10 d of age but were strongly affected by iron status at 20 d of age. Thus, mechanisms that regulate iron homeostasis are developed at the time of weaning. Overall, studies in human infants and experimental animals suggest that iron homeostasis is absent or limited early in infancy largely because of a lack of regulation of the iron transporters DMT1 and ferroportin.

Keywords: children, infant, iron, iron absorption, iron homeostasis, iron status

INFANT NEEDS FOR IRON

Normal-birth-weight, healthy, term infants are born with considerable liver iron stores and high hemoglobin concentrations, which, together, are usually sufficient to maintain their iron needs for growth and metabolism during the first 6 mo of life (1). The comparatively low iron content in human milk results in dietary iron being a minor supply, but together with iron from stores and recycled hemoglobin, it is usually adequate to meet iron needs because exclusively breastfed infants rarely show any signs of iron deficiency (ID) during the first 6 mo of life (2, 3). With typical breast milk intake of 780 mL/d and an iron concentration of ∼0.35 mg/L, daily intake of 0.27 mg Fe is believed to be adequate for infants at this age (4).

Preterm and low-birth-weight infants exhaust their iron stores earlier because they have lower fetal iron stores and proportionately greater weight gain than term infants do (1). The size of their iron stores is strongly affected by birth weight and gestational age. Because the transfer of iron from maternal blood to the fetus occurs mostly during the third trimester (5), infants who are born prematurely have lower iron stores. This is further compounded by the loss of blood from frequent phlebotomies during hospitalization. Therefore, iron requirements of preterm and low-birth-weight infants are higher, and iron supplementation becomes necessary before 6 mo of age (6, 7).

The timing of umbilical cord clamping and maternal iron status also affects iron stores of the newborn. Early cord clamping decreases iron transfer to the infants, whereas delayed cord clamping increases the red blood cell (RBC) volume in the infants and consequently increases iron stores (8–10). Maternal ID does not appear to lower iron stores of the infant (11, 12), but maternal ID anemia (IDA) has a negative effect on iron status of the newborn. Infants of moderately and severely anemic mothers have low iron stores (13, 14), thus placing the infants at higher risk of ID at an early age (15–17). Taken together, iron requirements during the first 6 mo of life depend greatly on the iron stores of the infants at birth.

ASSESSMENT OF IRON ABSORPTION

The bioavailability of iron from the diet varies depending on the food sources, composition of the diet, and physiologic factors. Iron bioavailability can be assessed with the use of balance studies, radioisotopes, or stable isotopes (18). Balance studies require meticulous collections of stool and urine, are very difficult to perform with precision, and are rarely used today. When radioisotopes are used, the test food is usually labeled with the radioisotope 59Fe. Whole-body counting is used shortly after the ingestion of the labeled test food, and another count is made ∼14 d later. After correcting the count for radioactive decay and expressing it as a percentage of the postadministration count, a direct measure of retained 59Fe is obtained. Whole-body counting with the use of radioisotopes is a direct, simple, and possibly the most reliable measure for iron retention. Several carefully conducted studies in infants that have used radioiron have been performed in the past and have shown differences in iron absorption with age and diet (19–22). Because counting techniques at that time had similar precision as they do today, it is likely that results from these studies are still valid. However, concern about the safety of ionizing radiation exits. Although radioisotopes are still being used in adults, they are considered inappropriate to use in infants and children.

Currently, stable isotopes are used for iron-bioavailability studies, especially in infants (23). The amounts of stable isotopes that are administered depend on the natural abundance of the enriched isotopes, whereby those with the least natural abundance allow smaller amounts of tracers to be used to achieve measurable enrichments in the samples. This relation is important because high doses of iron can make a substantial contribution to the total iron content of the tested food, which, in turn, influences the absorption results. Unlike radioisotopes, stable isotopes do not emit radiation, and therefore, whole-body counting cannot be performed. Instead, the incorporation of the stable isotopes into hemoglobin is used as a measure of iron bioavailability. Because most newly absorbed iron is incorporated into reticulocytes for hemoglobin synthesis, the proportion of the stable isotopes in hemoglobin after ingestion of a labeled test food is used for assessing iron bioavailability. A blood sample is obtained ∼14 d after dosing, and isotopic enrichment of the blood sample is analyzed with the use of mass spectrometry. An inherent problem with the use of this method is the need to assume 80% incorporation into hemoglobin on the basis of studies in human adults despite the knowledge that incorporation is lower in infants. This difficulty leads to the underestimation of iron absorption (24) and may explain why most studies in infants that have used stable isotopes have shown a lower absorption of iron from breast milk and formula than have studies that have used radioisotopes.

On the basis of radioisotope methods, infants aged 6–7 mo absorb ∼50% of breast-milk iron (Table 1) (21). It has also been estimated that infants aged 11–13 mo absorb ∼10% of formula iron regardless of the iron concentration of the formula (22). In addition, breastfed infants ingest ∼0.3 mg Fe/d (4) and, thus, likely absorb 0.15 mg Fe/d. Therefore, with the assumption of a comparable absorption rate for iron from formula in infants who are <11 mo old and who would be expected to consume 1000 mL formula/d, these young infants would likely absorb 1.2 mg Fe/d from formula containing 12 mg/L (United States) and 0.7 mg Fe/d from formula containing 7 mg/L (Europe). Even in the case of formulas that contain lower iron concentrations such as 4 or 2 mg/L, the amount of iron absorbed (0.4 and 0.2 mg, respectively) would be higher than that from breast milk. In short, infant formulas contain considerably more iron than breast milk does and, with a 10% absorption rate, result in greater amounts of absorbed iron than what occurs when an infant is fed breast milk.

TABLE 1.

Iron absorption from infant diets (estimated)

| Diet and iron concentration | Absorption, % | Estimated amount of iron absorbed, mg |

| Breast milk, mg/L | ||

| 0.3 | 50 | 0.15 |

| Fortified formula, mg/L | ||

| 12 | 10 | 1.2 |

| 7 | 10 | 0.7 |

| 4 | 10 | 0.4 |

| 2 | 10 | 0.2 |

| 1.5 | 10 | 0.15 |

| Unfortified formula, mg/L | ||

| 0.7 | 10 | 0.07 |

CLINICAL TRIALS TO ASSESS INFANT NEEDS FOR IRON

We have conducted 2 clinical trials in Sweden to assess the appropriate concentration of iron to use in infant formula (25, 26). In both of these randomized controlled trials, breastfed infants served as a reference group. Healthy, term infants were recruited at 2–6 wk of age and were exclusively formula-fed or breastfed at ≤6 mo of age. Only small taste portions (tablespoons) of fruit purees and other low–iron-weaning foods were allowed between 4 and 6 mo of age, which was commensurate with recommendations for this age group. In the first study (25), the iron concentration of the standard formula was 7 mg/L, and the experimental formulas contained 4 mg/L. There was no IDA at 6 mo of age, and there were no significant differences in mean hemoglobin or serum ferritin (SF) concentrations between the groups, thereby suggesting that exclusive breastfeeding for 6 mo maintains satisfactory iron status and that a formula iron concentration of 4 mg/L is sufficient to also result in adequate iron status.

At the time of our second study, the iron concentration of regular formula in Sweden had been decreased to 4 mg/L and served as our control (26). The experimental formulas were targeted to contain 2 mg Fe/L, and 2 of the formulas contained this concentration, whereas a third formula (containing part of its iron in the form of lactoferrin) only contained 1.6 mg/L. At 6 mo of age, there was no IDA, and there were no significant differences in mean hemoglobin or SF concentrations in the groups. Although relatively limited in size, these results suggest that a formula iron concentration of 2 mg/L (or possibly 1.6 mg/L) is sufficient to maintain adequate iron status of healthy term infants ≤6 mo of age.

POTENTIAL ADVERSE EFFECTS OF IRON

It is well known that ferrous iron can affect the absorption of other divalent trace elements such as copper and zinc (27). Although specific transporters for each of these micronutrients have been described, relatively modest excesses of one of them can affect the absorption of another, although the mechanism or mechanisms behind this effect are unclear. In our study on the iron fortification of infant formula described previously, we showed that infants who were fed formula with a concentration of 7 mg Fe/L (similar to the concentration of most formulas in Europe) had significantly lower concentrations of serum copper and the copper-dependent enzyme ceruloplasmin than did infants who were fed formula with 4 mg Fe/L and breastfed infants (25). To our knowledge, it is not yet known if this modest decrease in copper status has any functional consequences in the infants. In our study in Honduras and Sweden in which breastfed infants were given iron drops or a placebo daily from 4 to 9 or 6 to 9 mo of age, both groups who were given iron drops had significantly lower concentrations of the copper-dependent enzyme superoxide dismutase in their erythrocytes than those of infants given a placebo at 9 mo of age (28), thereby also suggesting lower copper status. In neither study was an effect on serum zinc observed; however, serum zinc is affected by many factors and is not a sensitive indicator of zinc status. In a study in Indonesia, infants were given daily supplements of iron, zinc, iron plus zinc, or a placebo from 6 to 12 mo of age (29). In the group who were given iron only, a significantly larger proportion of the infants had low plasma zinc concentrations than in the placebo group, thereby suggesting that there is a negative effect of iron on zinc absorption. Friel et al. (30) fed low-birth-weight infants formula with 2 different concentrations of iron (13.4 and 20.7 mg/L) and showed significantly lower concentrations of plasma zinc at 12 mo of age in infants who were fed the higher concentration of iron, thus suggesting that this interaction also may occur in preterm infants who have a high requirement of iron.

Ferrous iron has pro-oxidative potential through the Haber-Weiss reaction, but few studies have assessed the effects of various iron intakes on markers of oxidation in infants. Friel et al. (31) showed that iron that was added to human milk and formulas that were fortified with iron increased oxidative stress in vitro. The authors also studied low-birth-weight infants who were given 2 amounts of iron supplementation and showed increased concentrations of glutathione peroxidase in infants who were fed the higher amount of iron (30). Glutathione peroxidase is known to increase under oxidative stress, but the authors stated that the elevated concentrations were within the normal range. Another report has suggested the effects of iron status and fortification on the RBC membrane fatty acid composition in children (32). We measured RBC fatty acid composition in our clinical trial on Swedish infants who were fed formula with 2 different concentrations of iron (2 compared with 4 mg/L) but showed no effect (26). However, the difference in iron intake between the groups was small.

Iron also has the potential to affect the gut microflora because several pathogens require iron for growth and proliferation and, consequently, are dependent on the iron supply in the gut (33). This topic is addressed in another section of this supplement (34).

WHEN DO EXCLUSIVELY BREASTFED INFANTS NEED ADDITIONAL IRON?

The current recommendation of the WHO is to provide breastfed infants with iron drops after 6 mo of age to prevent ID and IDA. At one time, the WHO considered lowering the age for this recommendation to 4 mo. Therefore, in a USDA-funded study (35), we assessed whether there would be any advantages of introducing iron drops at 4 mo of age than at 6 mo of age. The study was conducted at the following 2 different sites: Honduras, to represent a lower socioeconomic group with compromised iron status of pregnant women and infants; and Sweden, representing a higher socioeconomic group with adequate maternal iron status and few infants with low iron status. The study was a double-blind randomized controlled study in which breastfed infants received either a placebo or iron drops (1 mg · kg−1 · d−1) from 4 or 6 to 9 mo of age. Infants at baseline (4 mo) had, as intended, very different iron statuses at the 2 sites. In Honduras, iron drops significantly improved the iron status of the infants, whereas this was not shown in Sweden. However, there was no significant difference between infants who received iron from 4 or 6 mo of age, which showed that there was no advantage with regard to the prevention of ID or IDA of introducing iron drops earlier than currently recommended. Friel et al. (36) have suggested that breastfed infants should be given iron earlier than currently recommended (6 mo of age). In their study, breastfed infants were given iron drops (7.5 mg/d) or a placebo from 1 to 6 mo of age, and iron status was assessed at 1, 3.5, 6, and 12 mo of age. At 6 mo of age only, hemoglobin concentrations were significantly higher in infants who were given iron than in those who received the placebo. This result is similar to our finding that Swedish breastfed infants with excellent iron status who were given iron drops had increased hemoglobin concentrations at 6 mo of age (35), thereby showing a lack of downregulation of iron absorption. Friel et al. (36) also showed higher visual acuity and psychomotor-development indexes at 13 mo of age and suggested that iron supplementation may have beneficial developmental effects for some infants. However, this study was underpowered to assess cognitive development, and dropout rates were high. In addition, many infants did not adhere to the protocol, which further limited the strength of this study.

The Committee on Nutrition of the American Academy of Pediatrics currently recommends supplementing breastfed infants with 1 mg Fe · kg−1 · d−1 orally beginning at 4 mo of age (37). The evidence supporting this recommendation appears to be very limited. Although it is evident that not all infants are protected against ID during the first 6 mo of life, a study by Ziegler et al. (2) showed that only 3% of term, healthy breastfed infants had ID at 6 mo of age, which was similar to the percentages of several European countries (3). Similarly, IDA only occurs in a small percentage of term, healthy breastfed infants at 6 mo of age.

In addition, it is questionable whether this early supplementation compared with WHO recommendations is effective; in the study by Ziegler et al. (2), iron drops from 1 to 5.5 mo of age had no effect on hemoglobin, and the small increase in SF indicating larger stores that were present at 4 and 5.5 mo of age had disappeared by 7 mo of age. Considering the adverse effects of iron supplementation on growth that has been observed in the study by Ziegler et al. (38) and others (39), perhaps the notion of inflict no harm should override the potential preventive effect against ID and IDA in a limited proportion of infants. More clinical studies are needed on both the beneficial and adverse effects of providing different amounts of iron to breastfed and formula-fed infants and the timing of such provisions.

LACK OF IRON HOMEOSTASIS AT YOUNG AGE

To us, a surprising finding in our study in Honduras and Sweden was that infants at both sites who received iron supplements had significantly increased hemoglobin concentrations at 6 mo of age (35). Iron status is known to have a strong effect on iron homeostasis in adults with individuals who have adequate iron status absorbing much less iron than individuals do who have low iron status. In our study, the iron status of the Honduran infants was much lower than that of the Swedish infants, but the Honduran infants appeared to absorb as much iron as was reflected in hemoglobin concentration increases. However, between 6 and 9 mo of age, the Honduran infants had a significant increase in hemoglobin concentrations when they were given iron drops, whereas Swedish infants did not. This result strongly suggests that young infants have a lower capacity to regulate iron homeostasis.

We followed this trial with a stable-isotope study in a cohort of the Swedish infants (40). Fasted, breastfed infants were given breast milk that was labeled with 58Fe and a reference dose of 57Fe (in apple juice), and the isotope incorporation into RBCs was measured. At 6 mo of age, there was no significant difference in the iron absorption between infants who had received iron drops daily from 4 mo of age and those who had received a placebo, which showed that high iron intake, which should correspond to adequate iron status, had no effect on iron homeostasis at this age. In our previous study (35), infants who were given iron drops daily for 2 or 5 mo, respectively, should have had better iron status than infants who had not, but this outcome was not confirmed. However, infants with high hemoglobin concentrations (showing an effect of the daily iron) had similar iron absorption at 6 mo of age as that of infants who had low hemoglobin.

However, at 9 mo of age, infants who had received iron daily had significantly lower iron absorption than infants did who had not received iron daily. Thus, at this age, infants appear to have a capacity to downregulate iron absorption when their iron intakes are high. It has been shown that iron absorption is more closely related to iron status (stores) than to daily iron intake in 12–48-mo-old infants (41). Iron absorption as measured by 58Fe was strongly inversely correlated to SF concentrations, whereas there was no significant correlation with dietary iron intake. It should also be emphasized that infants may be more capable of upregulating iron absorption when iron status is low than of downregulating iron absorption when iron status is adequate. It has been shown, in breastfed Peruvian infants who often have compromised iron status, that ID but not IDA upregulates iron absorption at 5–6 and 9–10 mo of age as indicated by a significant correlation with SF concentrations (42). In support of a lack of downregulation of iron absorption in presumably iron-sufficient Canadian infants, Friel et al. (36) have shown that indicators of iron status (hemoglobin and SF concentrations) increased significantly in breastfed infants who were given iron drops from 1 to 6 mo of age, which is an age when most breastfed infants still have ample iron stores.

It should be emphasized that the relations in iron intake, hemoglobin, and SF are complex and may change with age, particularly in infants and young children. In a study in Swedish infants who were fed iron-fortified cereals or iron-fortified formula (43), we showed that dietary iron intake from 6 to 8 and 9 to 11 mo of age was associated with hemoglobin concentrations at 9 and 12 mo of age, respectively, but iron intake from 12 to 18 mo of age was not associated with hemoglobin concentrations at 18 mo of age. In contrast, iron intake from 9 to 11 mo of age was not associated with SF concentrations at 9 and 12 mo of age, whereas iron intake from 12 to 17 mo of age was positively associated with SF concentrations at 18 mo of age. These observations suggest that there are developmental changes in the channeling of iron to erythropoiesis relative to storage in the absence of IDA.

MECHANISM REGULATING IRON HOMEOSTASIS

It is well known that a set of finely tuned iron transporters, hormones, and transcription factors have the capacity to strongly regulate iron absorption during both ID and iron excess in the adult (44–46). Ferrous iron is taken up by the iron transporter divalent metal-ion transporter 1 (DMT1) that is located at the surface of the intestinal epithelial cell, and its cellular expression is regulated by an iron-regulatory protein that binds to an iron-regulatory element to regulate messenger RNA stability and, thus, gene expression. In experimental animals, the membrane-bound ferric reductase duodenal cytochrome B has been shown to affect iron absorption, but this effect has been questioned in humans who have low intestinal ferric reductase activity and absorb ferric iron very poorly. Intracellularly, ferritin will bind iron, but it is not believed to be involved in the regulation of iron absorption. Ferroportin is located on the basolateral membrane and regulates iron efflux from the cell into the systemic circulation at which time ferrous iron is oxidized to ferric iron by hephaestin to bind to transferrin. Hepcidin is a small peptide that is synthesized by the liver in increasing amounts when iron status (liver iron) increases and is secreted into the bloodstream to reach target tissues. In the small intestine, hepcidin binds to ferroportin, which causes its internalization and degradation, thereby decreasing iron export out of the cell. As a consequence, cellular iron increases, which causes the down-regulation of DMT1, thereby reducing iron absorption. More recently, the transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor-2α has been shown to play a pivotal role in the regulation of iron absorption (46). Studies of these regulators of iron absorption have mostly been done in human adults (to a limited extent) and in experimental animals, and thus, there is very limited information on human infants. This lack is largely due to difficulties in obtaining intestinal tissue from healthy infants. However, hepcidin, which is analyzed in serum, appears to be regulated in a manner that is similar to that in adults (47) and has been suggested as a marker of iron status. Nevertheless, similar to SF, hepcidin is also affected by inflammation.

ANIMAL MODELS TO STUDY IRON HOMEOSTASIS AT YOUNG AGE

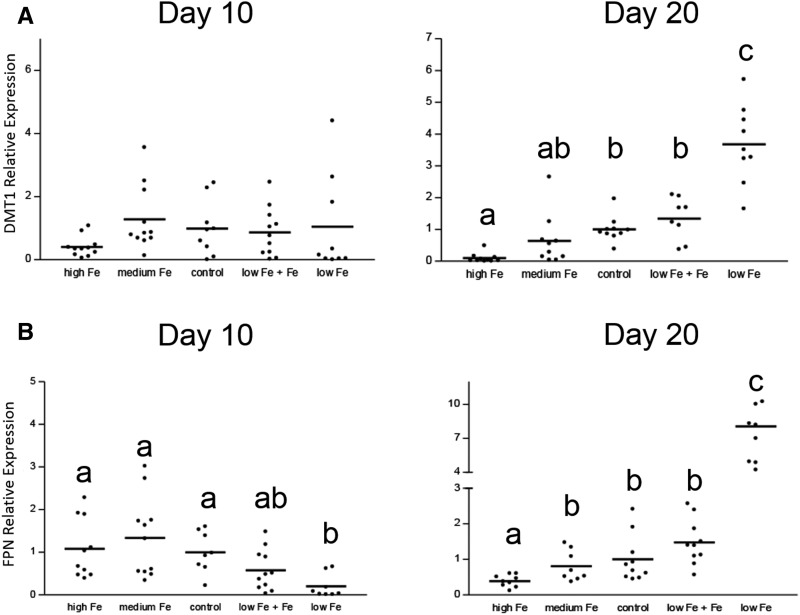

We have used a suckling rat-pup model to study the effects of iron status on iron homeostasis and the molecular mechanisms that regulate homeostasis in the small intestine at young age (48, 49). In the first study, pups from control dams were gavaged from birth to ≤20 d of age with a placebo or iron drops daily at a dose per body weight that was similar to that of infants who were fed iron-fortified formula (48). Iron absorption and retention was assessed with the use of 59Fe at 10 d of age, at which time the dams were fully lactating, and pups were exclusively nursed, which possibly corresponded in age to that of exclusively breastfed infants at 3–4 mo of age, and at 20 d of age, at which time the pups had started ingesting solid foods and were partially weaned, which possibly corresponded physiologically to partially weaned human infants at 8–9 mo of age. Cohorts of pups were killed at the same ages, and the gene expression of the major iron transporters DMT1 and ferroportin and the protein expression of ferritin were assessed. On day 10, there was no effect of iron supplementation on iron absorption or the expression of DMT1 or ferroportin. In contrast, on day 20, iron absorption was significantly lower with iron supplementation, and the expression of DMT1 and ferroportin was downregulated (Figure 1). These results showed that young (day-10) rat pups are unable to homeostatically regulate iron absorption, whereas older rat pups are able to do so. In the second study, rat pups were made ID from birth by feeding pregnant and lactating dams an iron-deficient diet (49). One cohort of these pups was given iron drops daily at the same amount as in the previous study. Unsupplemented ID pups and control pups were gavaged daily with a placebo. As previously, iron absorption was assessed at days 10 and 20. On day 10, iron uptake, mucosal retention, and total iron absorption were not affected by ID or iron supplementation. DMT1 was unchanged, whereas ferroportin was decreased. At day 20, DMT1 increased 4-fold, and ferroportin increased 8-fold, in the ID group compared with in controls. Body iron uptake and total iron absorption were increased, whereas mucosal iron retention decreased with ID. Iron supplementation of the ID pups normalized expression levels of the iron transporters, body iron uptake, mucosal iron retention, and total iron absorption to those of controls. Thus, the molecular mechanisms regulating iron absorption during early infancy differed from late infancy. In the latter, they were similar to those of adult animals, which indicated the developmental regulation of iron homeostasis.

FIGURE 1.

Intestinal expression of DMT1 (A) and FPN (B) at days 10 and 20 in control and iron-deficient suckling rat pups that were given iron daily shows that iron homeostasis is immature at a young age (nursing) but matures during weaning (adapted from references 48 and 49 with permission). Each dot represents one rat pup. Groups with different lowercase letters are significantly different, P = 0.0001 (1-factor ANOVA; Tukey’s test); the comparison was within the same time point only. DMT1, divalent metal-ion transporter 1; FPN, ferroportin.

Frazer et al. (50) explored the reasons for the very high absorption of iron during the neonatal period in the rat and showed that DMT1 and ferroportin were expressed in all areas of the small intestine and the colon, which is in contrast with adults in whom iron absorption mostly occurs in the duodenum. Thus, there is much more surface area and time available to absorb iron in the neonatal rat. In a subsequent study (51), they showed that the expression of ferroportin was very low up to day 15 of age in suckling rats and that iron absorption was hyporesponsive to hepcidin (induced by iron or LPS), possibly explaining the high iron absorption at this age. The role of ferroportin in iron absorption needs further research because both we (48, 49) and Frazer et al. (50) found ferroportin expression at an early age and also that the intestine-specific deletion of the ferroportin gene caused anemia by 15 d of age, which showed the involvement in iron acquisition at a young age.

CONCLUSION

Studies in human infants and experimental animals suggest that iron homeostasis is absent or limited in early infancy, which is largely due to a lack of regulation of the iron transporters DMT1 and ferroportin. The high and unregulated absorption of iron in the newborn period may confer developmental benefits but raises the possibility of excessive iron accumulation.

Acknowledgments

The author’s responsibilities were as follows—conducted the review, wrote the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript. BL is emeritus in the Department of Nutrition at University of California, Davis. The author reported no conflict of interest related to the study.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: DMT1, divalent metal-ion transporter 1; ID, iron deficiency; IDA, iron deficiency anemia; RBC, red blood cell; SF, serum ferritin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Collard KJ. Iron homeostasis in the neonate. Pediatrics 2009;123:1208–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ziegler EE, Nelson SE, Jeter JM. Iron supplementation of breastfed infants from an early age. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:525–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziegler EE, Nelson SE, Jeter JM. Iron supplementation of breastfed infants. Nutr Rev 2011;69 Suppl 1:S71–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine Food Nutrition Board. Dietary reference intakes: vitamin A, vitamin K, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium and zinc. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lukens JN. Iron metabolism and iron deficiency. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dewey KG, Cohen RJ, Rivera LL, Brown KH. Effects of age of introduction of complementary foods on iron status of breast-fed infants in Honduras. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;67:878–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gartner LM, Morton J, Lawrence RA, Naylor AJ, O’Hare D, Schanler RJ, Eidelman AI. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2005;115:496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grajeda R, Perez-Escamilla R, Dewey KG. Delayed clamping of the umbilical cord improves hematologic status of Guatemalan infants at 2 mo of age. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65:425–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta R, Ramji S. Effect of delayed cord clamping on iron stores in infants born to anemic mothers: a randomized controlled trial. Indian Pediatr 2002;39:130–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaparro CM, Neufeld LM, Tena Alavez G, Eguia-Liz Cedillo R, Dewey KG. Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping on iron status in Mexican infants: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2006;367:1997–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harthoorn-Lasthuizen EJ, Lindemans J, Langenhuijsen MM. Does iron-deficient erythropoiesis in pregnancy influence fetal iron supply? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001;80:392–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siimes AS, Siimes MA. Changes in the concentration of ferritin in the serum during fetal life in singletons and twins. Early Hum Dev 1986;13:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singla PN, Tyagi M, Shankar R, Dash D, Kumar A. Fetal iron status in maternal anemia. Acta Paediatr 1996;85:1327–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasmussen K. Is there a causal relationship between iron deficiency or iron-deficiency anemia and weight at birth, length of gestation and perinatal mortality? J Nutr 2001;131:590S–601S; discussion 601S–3S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colomer J, Colomer C, Gutierrez D, Jubert A, Nolasco A, Donat J, Fernandez-Delgado R, Donat F, Alvarez-Dardet C. Anaemia during pregnancy as a risk factor for infant iron deficiency: report from the Valencia Infant Anaemia Cohort (VIAC) study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1990;4:196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Pee S, Bloem MW, Sari M, Kiess L, Yip R, Kosen S. The high prevalence of low hemoglobin concentration among Indonesian infants aged 3-5 months is related to maternal anemia. J Nutr 2002;132:2215–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilbride J, Baker TG, Parapia LA, Khoury SA, Shuqaidef SW, Jerwood D. Anaemia during pregnancy as a risk factor for iron-deficiency anaemia in infancy: a case-control study in Jordan. Int J Epidemiol 1999;28:461–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fomon SJ, Nelson SE, Ziegler EE. Retention of iron by infants. Annu Rev Nutr 2000;20:273–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinrich HC, Bartels H, Götze C, Schäfer KH. [Normal range of intestinal iron absorption in newborns and infants.] Klin Wochenschr 1969;47:984–91 (in German). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Götze C, Schäfer KH, Heinrich HC, Bartels H. [Studies of iron metabolism in premature and healthy mature newborn infants during the 1st year of life with a whole body counter and other methods]. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 1970;118:210–3 (in German). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saarinen UM, Siimes MA, Dallman PR. Iron absorption in infants: high bioavailability of breast milk iron as indicated by the extrinsic tag method of iron absorption and by the concentration of serum ferritin. J Pediatr 1977;91:36–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saarinen UM, Siimes MA. Iron absorption from infant milk formula and the optimal level of iron supplementation. Acta Paediatr Scand 1977;66:719–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abrams SA. Using stable isotopes to assess mineral absorption and utilization by children. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;70:955–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fomon SJ, Ziegler EE, Serfass RE, Nelson SE, Rogers RR, Frantz JA. Less than 80% of absorbed iron is promptly incorporated into erythrocytes of infants. J Nutr 2000;130:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lönnerdal B, Hernell O. Iron, zinc, copper and selenium status of breast-fed infants and infants fed trace element fortified milk-based infant formula. Acta Paediatr 1994;83:367–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernell O, Lönnerdal B. Iron status of infants fed low-iron formula: no effect of added bovine lactoferrin or nucleotides. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:858–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lönnerdal B. Iron-zinc-copper interactions. In: Micronutrient interactions: impact on child health and nutrition. Washington: (DC): USAID and FAO, ILSI Press; 1998. p. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Domellöf M, Dewey KG, Cohen RJ, Lönnerdal B, Hernell O. Iron supplements reduce erythrocyte copper-zinc superoxide dismutase activity in term, breastfed infants. Acta Paediatr 2005;94:1578–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lind T, Lönnerdal B, Stenlund H, Ismail D, Seswandhana R, Ekström EC, Persson LÅ. A community-based randomized controlled trial of iron and zinc supplementation in Indonesian infants: interactions between iron and zinc. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;77:883–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friel JK, Andrews WL, Aziz K, Kwa PG, Lepage G, L’Abbe MR. A randomized trial of two levels of iron supplementation and developmental outcome in low birth weight infants. J Pediatr 2001;139:254–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friel JK, Martin SM, Langdon M, Herzberg GR, Buettner GR. Milk from mothers of both premature and full-term infants provides better antioxidant protection than does infant formula. Pediatr Res 2002;51:612–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smuts CM, Tichelaar HY, van Jaarsveld PJ, Badenhorst CJ, Kruger M, Laubscher R, Mansvelt EP, Benade AJ. The effect of iron fortification on the fatty acid composition of plasma and erythrocyte membranes in primary school children with and without iron-deficiency. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 1994;51:277–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paganini D, Uyoga MA, Zimmermann MB. Iron fortification of foods for infants and children in low-income countries: effects on the gut microbiome, gut inflammation, and diarrhea. Nutrients 2016;8:pii: E494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paganini D, Zimmermann MB. The effects of iron fortification and supplementation on the gut microbiome and diarrhea in infants and children: a review. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;106(Suppl):1688S–93S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Domellöf M, Cohen RJ, Dewey KG, Hernell O, Rivera LL, Lönnerdal B. Iron supplementation of breast-fed Honduran and Swedish infants from 4 to 9 months of age. J Pediatr 2001;138:679–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friel JK, Aziz K, Andrews WL, Harding SV, Courage ML, Adams RJ. A double-masked, randomized control trial of iron supplementation in early infancy in healthy term breast-fed infants. J Pediatr 2003;143:582–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baker RD, Greer FR. Diagnosis and prevention of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children (0-3 years of age). Pediatrics 2010;126:1040–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ziegler EE, Nelson SE, Jeter JM. Iron status of breastfed infants is improved equally by medicinal iron and iron-fortified cereal. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;90:76–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lönnerdal B. Excess iron intake as a factor in growth, infections, and development of infants and young children. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;106(Suppl):1681S–7S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Domellöf M, Lönnerdal B, Abrams SA, Hernell O. Iron absorption in breast-fed infants: effects of age, iron status, iron supplements, and complementary foods. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lynch MF, Griffin IJ, Hawthorne KM, Chen Z, Hamzo MG, Abrams SA. Iron absorption is more closely related to iron status than to daily iron intake in 12- to 48-mo-old children. J Nutr 2007;137:88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hicks PD, Zavaleta N, Chen Z, Abrams SA, Lönnerdal B. Iron deficiency, but not anemia, upregulates iron absorption in breast-fed peruvian infants. J Nutr 2006;136:2435–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Domellöf M, Lind T, Lönnerdal B, Persson LA, Dewey KG, Hernell O. Effects of mode of oral iron administration on serum ferritin and haemoglobin in infants. Acta Paediatr 2008;97:1055–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gulec S, Anderson GJ, Collins JF. Mechanistic and regulatory aspects of intestinal iron absorption. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2014;307:G397–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo S, Frazer DM, Anderson GJ. Iron homeostasis: transport, metabolism, and regulation. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2016;19:276–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simpson RJ, McKie AT. Regulation of intestinal iron absorption: the mucosa takes control? Cell Metab 2009;10:84–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berglund S, Lönnerdal B, Westrup B, Domellöf M. Effects of iron supplementation on serum hepcidin and serum erythropoietin in low-birth-weight infants. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:1553–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leong WI, Bowlus CL, Tallkvist J, Lönnerdal B. Iron supplementation during infancy–effects on expression of iron transporters, iron absorption, and iron utilization in rat pups. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;78:1203–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leong WI, Bowlus CL, Tallkvist J, Lönnerdal B. DMT1 and FPN1 expression during infancy: developmental regulation of iron absorption. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2003;285:G1153–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frazer DM, Wilkins SJ, Anderson GJ. Elevated iron absorption in the neonatal rat reflects high expression of iron transport genes in the distal alimentary tract. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2007;293:G525–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Darshan D, Wilkins SJ, Frazer DM, Anderson GJ. Reduced expression of ferroportin-1 mediates hyporesponsiveness of suckling rats to stimuli that reduce iron absorption. Gastroenterology 2011;141:300–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]