Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a text messaging intervention to increase contraception among adolescent emergency department patients.

Methods

A pilot randomized controlled trial of sexually active females aged 14–19 receiving 3 months of theory-based, unidirectional educational and motivational texts providing reproductive health information versus standardized discharge instructions. Blinded assessors measured contraception initiation via telephone follow-up and health record review at 3 months.

Results

We randomized 100 eligible participants (predominantly aged 18–19, Hispanic, and with a primary provider); 88.0% had follow-up. In the intervention arm, 3/50 (6.0%) participants opted out, and 1,172/1,654 (70.9%) texts were successfully delivered; over 90% of message failures were from one mobile carrier. Most (36/41; 87.7%) in the intervention group liked and wanted future reproductive health messages. Contraception was initiated in 6/50 (12.0%) in the intervention arm and in 11/49 (22.4%) in the control arm.

Conclusions

A pregnancy prevention texting intervention was feasible and acceptable among adolescent females in the emergency department setting.

Keywords: Pregnancy in adolescence, Reproductive health, Contraception, Text messaging

Female adolescents seeking emergency department (ED) care are at particularly high-risk of unintended pregnancy, primarily due to nonuse of contraception [1]. However, ED physicians are reluctant to provide preventive reproductive care, and few ED patients follow up for primary care when referred [2,3].

Text messaging (TM) has the potential to lead to behavior change, although little data from patients in the ED exist [4–7]. Our objective was to determine the feasibility and acceptability of an ED-based texting intervention to increase contraception initiation among adolescent females at high risk of pregnancy.

Methods

We conducted a randomized trial from January to November 2014 in an urban ED (ClinicTrials.gov [#NCT02093884]). The Institutional Review Board approved this study with requirement for written informed consent from the patient; parental consent was waived.

Adolescent females aged 14–19 who were sexually active with males in the past 3 months and presented to the ED for a reproductive health complaint, such as but not limited to vaginal bleeding or discharge, dysuria, and abdominal pain, were eligible. We targeted females with reproductive complaints based on the Sentinel Event Model [8]. We excluded patients using effective contraceptive methods (intrauterine device, implant, injection, ring, patch, or oral contraceptive) and who were pregnant, were cognitively impaired, had no mobile phone, or did not speak English or Spanish. We did not exclude patients based on pregnancy intentions, as adolescent ambivalence toward pregnancy is common [1,9].

Participants completed a baseline questionnaire with questions primarily adapted from the Youth Risk Behavioral Survey and National Survey of Family Growth [10,11]. Participants received a $20 gift card and were block randomized 1:1, with allocation concealed by a software program. Outcome assessors were blinded to the study arm.

The TM arm received unidirectional (one-way) texts for 3 months, containing an education and action component, in English or Spanish. Text content, dosing, and schedule were based on a modified Health Belief Model and on our prior work that identified barriers and enablers to using contraceptives [12,13]. Each participant was sent identical message series and timing, comprising 33 texts, delivered between 12:00 to 21:00, ranging from daily to every 5 days over 3 months (Appendix S1).

The standard referral (SR) arm consisted of a wallet card advertising a walk-in family planning clinic and a standardized monologue given by the ED physicians describing the need for reproductive care [3].

Although patients in the TM arm neither received a wallet card nor a standardized physician monologue, they did receive written or spoken discharge instructions at the discretion of their physician attending. Information about the family planning clinic was incorporated into the text messages.

To assess feasibility, we examined rates of screening, recruitment, randomization, retention, opt-outs (to stop receiving messages), and technological failures [14]. Text message delivery rates were reported by our mobile platform service. To assess acceptability, we assessed interest in future messages, liking the messages, preferences for distribution schedule, and concerns about cost or safety during phone call follow-up. The popularity of website links was reported by our mobile platform. We measured our primary outcome, “effective contraception initiation,” via electronic medical record (EMR) documentation and self-report on 3-month follow-up. Secondary outcomes were collected similarly and included the proportion of participants attending family planning clinics, receiving contraception counseling, and becoming pregnant.

The intention-to-treat (ITT) population included all randomized patients. The per-protocol population included participants who completed follow-up and excluded intervention group participants who received no texts. Our pilot sample size was based on recruitment pragmatics, such as our grant time frame and research coordinator availability [14].

Results

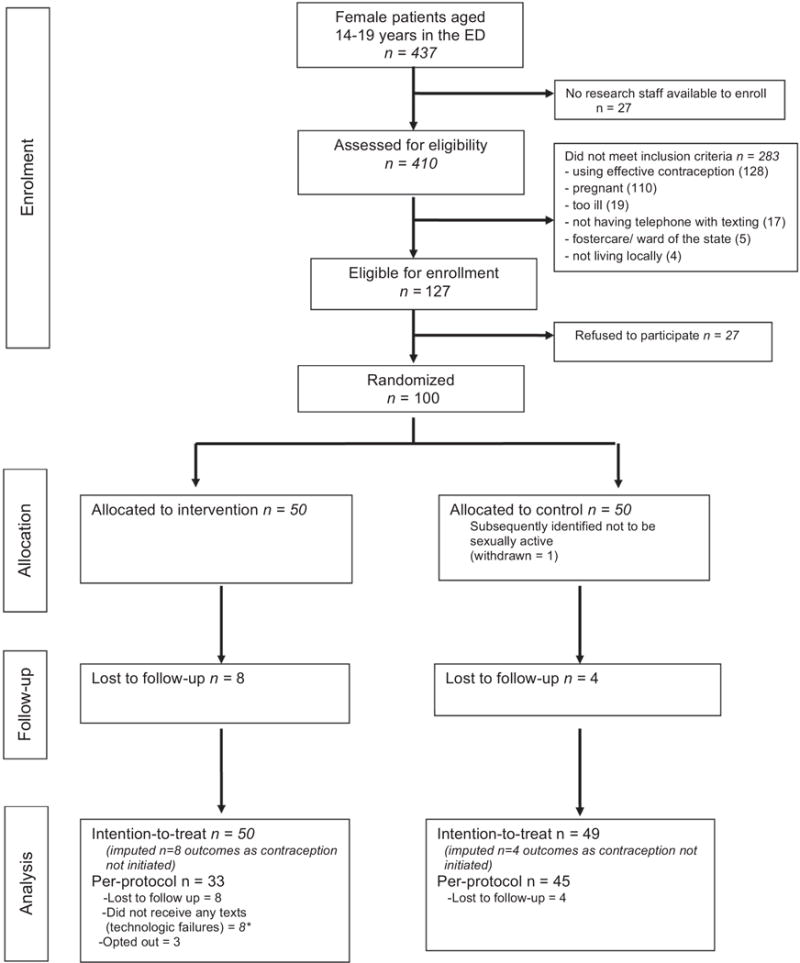

We enrolled 100 females; one patient was withdrawn (Figure 1). The enrollment acceptance rate was 78.8% (100/127). Table 1 details baseline characteristics. The ITT and per-protocol populations consisted of 99 and 78 patients, respectively.

Figure 1.

CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram. *Two participants who did not receive any of the texts messages in the intervention group were also lost to follow-up.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Variable | Text messaging (%) (N = 49)a |

Standard referral (%) (N = 49) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age | ||

| 14–17 | 11 (22.4) | 12 (24.4) |

| 18–19 | 38 (77.6) | 37 (75.6) |

| Hispanic | 41 (83.7) | 45 (91.8) |

| Race | ||

| American Indian/Alaska native | 2 (4.1) | 2 (4.1) |

| Asian | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) |

| Black/African-American | 7 (14.3) | 7 (14.3) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 4 (8.2) |

| White | 6 (12.2) | 0 (0) |

| More than one | 8 (16.3) | 14 (28.6) |

| Don’t know | 25 (51.0) | 22 (44.9) |

| Born in the U.S. | 41 (83.7) | 38 (77.6) |

| Has any type of insurance | 39 (79.6) | 39 (79.6) |

| Use of medical care | ||

| Has a primary care doctor | 38 (77.6) | 39 (79.6) |

| ED visit in the past 3 months | 19 (38.8) | 26 (53.1) |

| Ever been to family planning clinic | 7 (14.3) | 13 (26.5) |

| Sexual history | ||

| First sexual intercourse age ≤14 | 15 (30.6) | 19 (38.8) |

| Lifetime sexual partners ≥5 | 13 (26.5) | 15 (30.6) |

| Two or more sexual partners in the past 3 months | 13 (26.5) | 7 (14.3) |

| Ever used effective contraception | 27 (55.1) | 29 (59.2) |

| Use of a condom at last intercourse | 16 (32.7) | 12 (24.5) |

| Ever used Plan B | 29 (59.2) | 30 (61.2) |

| Ever been pregnant | 15 (30.6) | 18 (36.7) |

| Talked to family about starting contraception in the past 3 months | 8 (16.3) | 16 (32.7) |

| Pregnancy intentions | ||

| How hard are you trying to get pregnant? | ||

| Trying to get pregnant | 9 (18.4) | 4 (8.2) |

| Not trying to get pregnant or to prevent | 23 (46.9) | 20 (40.8) |

| Trying to prevent getting pregnant | 17 (34.7) | 25 (51.0) |

| How much do you want to get pregnant now? | ||

| I want to be pregnant now. | 8 (16.3) | 4 (8.2) |

| I don’t care if I get pregnant now. | 5 (10.2) | 6 (12.2) |

| I don’t want to be pregnant. | 36 (73.5) | 39 (79.6) |

| How much are you planning to get pregnant? | ||

| I am planning hard to get pregnant. | 5 (10.2) | 5 (10.2) |

| I am planning a little to get pregnant. | 4 (8.2) | 2 (4.1) |

| I am not planning to get pregnant. | 40 (81.6) | 42 (85.7) |

| Wants a baby now | 5 (10.2) | 3 (6.1) |

| Partner wants participant to get pregnant | 11 (22.4) | 11 (22.4) |

One participant did not have characteristics recorded due to a technological error.

More participants in the intervention arm than in SR arm were lost to follow-up, (TM 8/50; 16.0% versus SR 4/49; 8.2%). In the TM arm, 41/50 (82.0%) participants completed phone call follow-up, with data for one additional participant available only via EMR review. In the SR arm, 38/49 (77.6%) participants completed phone call follow-up, with data for seven participants available only via EMR review.

In the intervention arm, eight participants (8/50; 16%) received no text messages, which were considered technological failures. A total of 36 (36/50; 72%) received at least half the messages; 25 (25/50; 50%) received the full intervention. Of all sent messages to the intervention group, 70.8% (1,168/1,650) of texts were successfully delivered; over 90% of message failures were due to one mobile carrier. Three participants (3/50; 6%) in the TM arm opted out.

Of 41 participants in the TM arm who completed follow-up, 36 (87.8%) wanted to receive future messages. The majority (31/41; 75.6%) reported reading half or more of the texts and “liked” the messages, particularly those about the family planning clinic, sexually transmitted infections, birth control, and condoms. The most popular websites clicked on were the family planning website and Bedsider.org. A total of 31/41 participants (75.6%) would not change texting frequency, while four wanted messages sent less frequently. No participant felt unsafe after receiving the messages.

In the ITT population, contraception initiation occurred in 6/50 (12.0%) in the TM arm and 11/49 (22.4%) in the SR arm. Overall contraception initiation, regardless of arm, was 34.8% among younger adolescents (8/23) and 11.8% in older adolescents (9/76). For our secondary effect outcomes, 16/50 (32.0%) in the TM arm and 15/49 (30.6%) in the SR arm attended family planning follow-up; 24 in the TM arm (24/50; 48.0%) and 23 in the SR arm (23/49; 46.9%) received contraception counseling. Nine participants (TM: 4/50, 8.0% versus SR: 5/49; 10.2%) became pregnant. At enrollment, the majority of these nine participants were not trying, did not want, were not planning, and did not have a partner who wanted them to become pregnant.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first ED-based pregnancy prevention intervention using mobile technology. The texting intervention was feasible, although with technological challenges. The intervention was acceptable, and females were receptive to future texts.

The major threat to feasibility was the high rate of texting failure due largely to a pay-as-you-go phone plan [6]. Some pay-as-you-go mobile providers block “short” code messages, which are texts coming from a five-digit number, as opposed to “long” code messages, which come from a 10-digit number. Future studies should select mobile platforms that can support the delivery of long code messages.

While acceptability was high, it was not unanimous, and contraceptive initiation was limited. One potential reason was that older adolescents, who have often spent more time in school-based health programs or talking to peers or family members, may have already been exposed to sexual health information and be less responsive than younger teens. Focusing on younger adolescents may capture them early after their first sexual experiences, a time when contraception patterns emerge.

The use of a more complex messaging might have enhanced the acceptability of our intervention. Recent literature suggests that pushing noninteractive messages to older teens with repetitive information or too often might cause disinterest [15]. The future of texting interventions may lie with innovative, bidirectional, tailored messaging, which changes behavior by creating an automated yet engaging conversation [4,5,7].

There were limitations. First, more participants in the TM arm were trying and wanting to become pregnant. Although participants were explained that this was a pregnancy prevention study, possibly those teens who were claiming to try or wanted to be pregnant were less likely to start contraceptives. Second, some study participants admitted to never starting the prescribed contraceptive. EMR documentation of any contraceptive started trumped self-report; however, self-report may be a more valid marker of initiation. Third, we reported technological failures based on a mobile platform report. This does not include data on how often messages may have been read or acknowledged by participants. Fourth, our population was predominantly Hispanic, limiting generalizability.

A pregnancy prevention ED-based intervention proved feasible and acceptable among adolescent females at high risk of pregnancy.

Supplementary Material

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTIONS.

A novel theory-based text message intervention to increase contraception initiation was feasible and acceptable among adolescent females at risk for unplanned pregnancy recruited from an emergency department.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This study was supported by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. This study was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grant number UL1 TR000040, formerly the National Center for Research Resources, grant number UL1 RR024156.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Trial registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT02093884.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This research was presented at the 2015 North American Forum on Family Planning and at the 2016 Pediatric Academic Society Annual meeting.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.07.021.

References

- 1.Chernick L, Kharbanda EO, Santelli J, Dayan P. Identifying adolescent females at high risk of pregnancy in a pediatric emergency department. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:171–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delgado MK, Acosta CD, Ginde AA, et al. National survey of preventive health services in US emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:104–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chernick LS, Westhoff C, Ray M, et al. Enhancing referral of sexually active adolescent females from the emergency department to family planning. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015;24:324–8. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranney ML, Freeman JR, Connell G, et al. A depression prevention intervention for adolescents in the emergency department. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:401–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suffoletto B, Kristan J, Callaway C, et al. A text message alcohol intervention for young adult emergency department patients: A randomized clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64:664–72, e4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stockwell MS, Kharbanda EO, Martinez RA, et al. Effect of a text messaging intervention on influenza vaccination in an urban, low-income pediatric adolescent population. JAMA. 2012;307:1702–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Head KJ, Noar SM, Iannarino NT, Grant Harrington N. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: A meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2013;97:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boudreaux ED, Bock B, O’Hea E. When an event sparks behavior change: An introduction to the sentinel event method of dynamic model building and its application to emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:329–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01291.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rocca CH, Hubbard AE, Johnson-Hanks J, et al. Predictive ability and stability of adolescents’ pregnancy intentions in a predominantly Latino community. Stud Fam Plann. 2010;41:179–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00242.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Center for Health Statistics. National survey of family growth. Centers for Disease Control; Published 2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/. Accessed January 9, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004;53(RR-12) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chernick LS, Schnall R, Higgins T, et al. Barriers to and enablers of contraceptive use among adolescent females and their interest in an emergency department based intervention. Contraception. 2015;91:217–25. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chernick LS, Schnall R, Stockwell MS, et al. Adolescent female text messaging preferences to prevent pregnancy after an emergency department visit: A qualitative analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18 doi: 10.2196/jmir.6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leon AC, David L, Kraemer H. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:626–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ranney ML, Thorsen M, Patena JV, et al. “You need to get them where they feel it”: Conflicting perspectives on how to maximize the structure of text-message psychological interventions for adolescents. Proc Annu Hawaii Int Conf Syst Sci. 2015:3247–55. doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2015.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.