Abstract

Addressing the social determinants of health (SDOH) that influence teen pregnancy is paramount to eliminating disparities and achieving health equity. Expanding prevention efforts from purely individual behavior change to improving the social, political, economic, and built environments in which people live, learn, work, and play may better equip vulnerable youth to adopt and sustain healthy decisions. In 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in partnership with the Office of Adolescent Health funded state- and community-based organizations to develop and implement the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Community-Wide Initiative. This effort approached teen pregnancy from an SDOH perspective, by identifying contextual factors that influence teen pregnancy and other adverse sexual health outcomes among vulnerable youth. Strategies included, but were not limited to, conducting a root cause analysis and establishing nontraditional partnerships to address determinants identified by community members. This article describes the value of an SDOH approach for achieving health equity, explains the integration of such an approach into community-level teen pregnancy prevention activities, and highlights two project partners’ efforts to establish and nurture nontraditional partnerships to address specific SDOH.

Keywords: community interventions, health disparities, partnerships, teen pregnancy, social determinants of health

INTRODUCTION

Eliminating disparities and achieving health equity is an overarching goal of Healthy People 2020 and many other public health entities (Office of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, n.d.). A social determinants of health (SDOH) approach expands prevention efforts from focusing purely on individual behavior change to improving the social, political, economic, and built environments in which people live, learn, work, and play, enabling all individuals to adopt, routinize, and sustain healthy choices. In particular, vulnerable populations experiencing health disparities face system-wide barriers to accessing needed services and making healthy choices. The SDOH approach is thus designed and equipped to address these barriers directly by targeting multiple levels of influence, such as the social and economic conditions that play support individual-level behavior change (Office of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, n.d.).

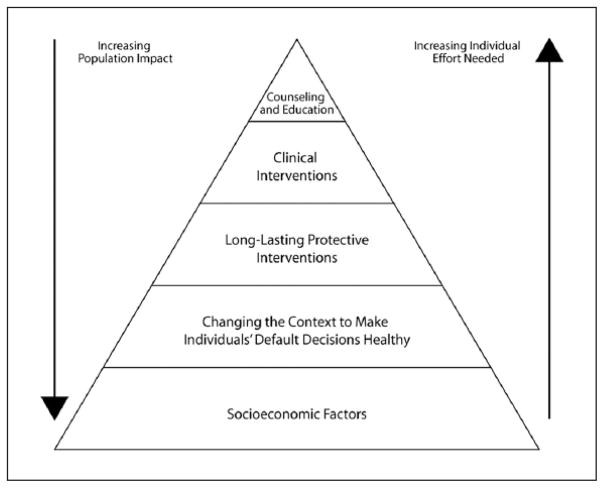

Dr. Thomas Frieden, Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), has discussed the economic benefits of system-wide public health prevention efforts that make healthy behaviors the default over the long-term versus the short-term impact individual behavioral interventions can have given their limited reach and the restricted resources and time frames under which they typically operate (Frieden, 2010). The health impact pyramid (Figure 1) illustrates the increasing societal impacts that can occur as one moves from spending effort and resources on the individual level, such as one-on-one counseling or education, to addressing socioeconomic factors (and other SDOH) for greatest population-wide effects.

FIGURE 1. The Health Impact Pyramid.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from “A Framework for Public Health Action: The Health Impact Pyramid,” by T. R. Frieden, 2010, American Journal of Public Health, 100, Figure 1. Copyright 2010 by the American Public Health Association.

In this article, we describe how an SDOH approach improved teen pregnancy prevention efforts by cultivating nontraditional partnerships as part of the CDC and Office of Adolescent Health (OAH) Teen Pregnancy Prevention Community-Wide Initiative (CWI). We discuss the value of an SDOH approach to achieving health equity, how we incorporated this approach into our efforts, and strategies used to identify pertinent SDOH that impact teen pregnancy at the community level. In addition, we present two examples that highlight nontraditional partnerships established to improve the health and well-being of vulnerable youth.

BACKGROUND

Teen birth rates in the United States have declined steadily and significantly over recent decades for all females ages 15 to 19 years, from 61.8 births per 1,000 in 1991 to 24.2 births per 1,000 in 2014 (Hamilton, Martin, Osterman, Curtin, & Mathews, 2015). This represents a 61% decline, yet geographic, socioeconomic, and racial and ethnic disparities persist (Gold, Kawachi, Kennedy, Lynch, & Connell, 2001; Hamilton et al., 2015). In 2014, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic teen birth rates were still more than twice that of non-Hispanic White teens, and the American Indian/Alaska Native rate also remained higher than the White teen birth rate. Southern and southwestern states have persistently higher rates than northern and eastern states, regardless of race/ethnicity. In addition, state teen birth rates ranged from the lowest rate of 10.6 per 1,000 in Massachusetts to the highest rate of 39.5 per 1,000 in Arkansas in 2014 (Hamilton et al., 2015).

These persistent disparities underscore the need to advance our understanding of SDOH specific to adolescent health. Teens are increasingly independent and have unique developmental needs in preparation for adult life (e.g., academic achievement, community engagement, peer relationships, and employment), so community and other external structural factors can be particularly important. In addition, while better understanding of causal mechanisms and other dynamics is needed, several SDOH have been identified as relevant to teen pregnancy and adolescent sexual health behaviors, independent of individual- or family-level measures (i.e., education and employment opportunities, neighborhood characteristics, community-level economic structures, and access to quality health care; Carlson, McNulty, Bellair, & Watts, 2013; Cubbin, Santelli, Brindis, & Braveman, 2005; Gold, Kennedy, Connell, & Kawachi, 2002; Maness, Buhi, Daley, Baldwin, & Kromrey, 2016; Penman-Aguilar, Carter, Snead, & Kourtis, 2013; Romero et al., 2016; Viner et al., 2012).

To adequately address SDOH and eliminate disparities, public health efforts must (1) identify SDOH that are feasible to address and (2) effectively engage partners that are well positioned to have an impact on those broader, “upstream” areas not typically within the purview of public health, such as economic opportunity. Such partners may often be “nontraditional” public health partners—those not usually engaged in health issues—such as transportation or city planning entities, housing, faith-based organizations, or a task force with diverse representation from public and private sectors (Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, 2011). Yet numerous potential challenges exist in the formation and sustainability of these partnerships, due to such realities as varying levels of capacity, diverse missions and goals, different priority populations, as well as the organizational culture of each partner involved (JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc., 2014).

STRATEGIES

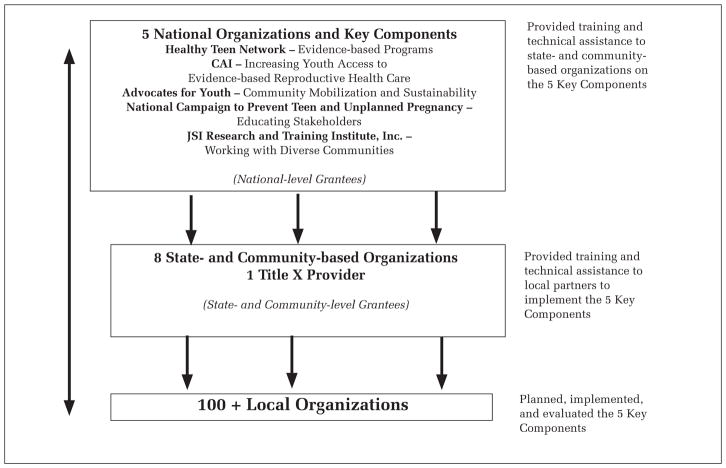

In 2010, CDC in partnership with the OAH funded eight state- and community-based organizations to develop and implement a multicomponent, community-wide approach to teen pregnancy prevention in targeted U.S. communities with a history of high rates of teen births. Additionally, CDC and the Office of Population Affairs supported a Title X (federal grant program providing comprehensive family planning and related preventive health services) organization to implement the same multicomponent, community-wide approach (see Mueller et al., in press, for an overview of CWI). The program’s five key components, each supported by a national organization also funded by CDC/OAH (Figure 2), reflected the understanding that effective, sustainable prevention efforts must occur on multiple levels, not just through individual behavior change interventions. The national partners provided direct training and technical assistance on the five key components to the nine state- and community-based partners, as well as local partnering agencies, who provided evidence-based programs and reproductive health services directly to youth (Mueller et al., in press).

FIGURE 2. Teen Pregnancy Prevention Community-Wide Initiatives Program Model.

NOTE: CAI = Cicatelli Associates; JSI = John Snow Research & Training Institute, Inc.

Awareness of the need to incorporate an SDOH approach within the CWI further evolved as a result of community needs assessments, surveys, and focus groups that were implemented by state and community partners at the project’s start. Barriers influencing access to reproductive health information and services and the adoption of healthy sexual choices were identified as social determinants (e.g., transportation, lack of educational or economic opportunity) of teen pregnancy. These findings demonstrated a need for state and community partners to explore new partnerships to address those determinants. The findings also gave CDC and its project partners the opportunity to further investigate the root causes of teen pregnancy and delve deeper into current research on SDOH, adolescents, and teen pregnancy. To support such efforts, JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc. (JSI), the funded national partner for the Working With Diverse Communities component, provided training and technical assistance to the state and community partners (Figure 2).

In order to have the greatest impact, CDC and national, state, and community project partners looked to uncover local underlying factors that influence teen pregnancy and the sexual health outcomes of vulnerable youth. As an initial step, JSI helped select state and community project partners conduct a root cause analysis (RCA) and develop an action plan with a cross-section of community stakeholders (e.g., youth serving agencies, health care providers, faith-based organizations, and school administrators). The RCA is a process used to identify the contributing factors and underlying causes of a problem, event, or health issue, such as teen pregnancy. It is based on the theory that addressing the root causes of an issue is more effective and efficient than focusing on the symptoms. Through this process stakeholders can gain a better understanding of the complexity of teen pregnancy and help solidify strategies to improve and enhance prevention efforts (JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc., 2013). In addition, the action planning process allows for the prioritization of feasible determinants and corresponding strategies to address them and for the selection of leverage points on which partners might work together to improve conditions for vulnerable youth in their communities. This process led to the establishment of nontraditional partnerships as a means to better address the social determinants of teen pregnancy and to strengthen and sustain community-wide teen pregnancy prevention efforts (JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc., 2013).

Examples are presented below of the processes used, successes achieved, and lessons learned from two CWI partners that identified SDOH that influence teen pregnancy in their communities and established nontraditional partnerships with community agencies already working to improve the well-being of youth.

Integrating Teen Pregnancy Prevention in Education and Career Training: City of Hartford Department of Health and Human Services and Hartford Job Corps

Hartford, Connecticut, experiences some of the state’s greatest health disparities (Hartford Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). The teen birth rate for Hartford was 28.5 per 1,000 for females aged 15 to 19 years in 2014, above the national average rate of 24.2 (Hamilton et al., 2015; Hartford Department of Health and Human Services, 2015). In 2013, as part of the CWI, the City of Hartford Department of Health and Human Services Teen Pregnancy Prevention Initiative (HTPPI) began exploring a partnership with the Hartford Job Corps. Hartford Job Corps was highly recommended as an ideal partner due to its focus on economic development among disadvantaged youth and young adults age 16 to 24 years.

Opened in 2004, Hartford Job Corps resulted from a multitiered community effort to bring jobs and boost alternative paths to success for young people in the greater Hartford area. As an education and career technical training program administered by the U.S. Department of Labor, Hartford Job Corps enrolls disadvantaged, low-income youth and young adults ages 16 to 24 years to improve their quality of life through career, technical, and academic training. The attainment of a high school diploma/GED by every qualified student is a primary goal of the program. Courses in independent living, employability, social and leadership skills, as well as wraparound services including medical, dental, and mental health services are also offered to help students transition into the workplace and gain life skills.

The initial collaboration began with HTPPI providing “Cupcakes and Condoms,” an interactive, educational presentation that discussed the various types of available contraceptive methods. Cupcakes and Condoms eventually led to a greater discussion between the two organizations about ways in which vulnerable youth and young adults could obtain adequate and accurate information about sexual health. Based on the needs demonstrated by the youth and young adults, it was determined that the implementation of an evidence-based program was appropriate and would integrate well into the ongoing Job Corp program. HTPPI then began to help staff assess needs, determine gaps and training needs, and develop implementation plans. Within the assessment process, the staff capacity and needs, as well as the needs of youth were all taken into consideration for selecting the best evidence-based program for implementation. As a result of these findings, along with the overall community assessment, Be Proud! Be Responsible! (BPBR) was selected as the curriculum for implementation (http://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/oah-initiatives/tpp_program/db/programs/ebp-bpbr.html). Eight Job Corps staff were trained in human sexuality and BPBR by HTPPI staff, implemented as part of core courses for all incoming students. A total of 317 Job Corps trainees participated in the program from May 2014 to October 2015. In addition, supplemental activities and booster sessions to reinforce prevention information were provided in the evenings and on the weekends approximately every 6 weeks. Furthermore, youth and young adults who participated in BPBR experienced an increase in condom use knowledge and were less likely to have sex without a condom at post-test compared to baseline. Overall, participants also reported being highly satisfied with both the program and facilitators (Connecticut Women’s Education and Legal Fund, 2015).

A few challenges encountered are worth mentioning, such as the need to adapt BPBR to include specific activities more appropriate for slightly older populations. For program implementation to be as successful as possible, staff had to ensure that the unique needs of the participants were being met. This required HTPPI to submit official adaptation requests to CDC for review and approval to make certain youth were receiving the most accurate, up-to-date, and appropriate information (e.g., language referring to teens was updated to be more inclusive of older adolescents and young adults, and outdated statistics and reference materials were updated). Additionally, the coordination of staff schedules and balance of staff effort was critical. To make this work, staff were designated specific roles and tasks depending on their skill sets and the needs of the youth and young adults. Thus it was important to implement a plan that had the most chance of success, keeping in mind that flexibility was also necessary to address unforeseen challenges and develop effective solutions to support the overall program.

The nontraditional partnership with Job Corps was one of HTPPI’s initial efforts to broaden its base to address health disparities and the SDOH by collaborating with an agency dedicated to the economic development of youth and young adults. This meant that self-care, self-efficacy, and healthy decision making would be communicated simultaneously with the promotion of economic security and life skills. Job Corps leadership and staff agreed about the important role of accurate sexual health and pregnancy prevention information to support education and employment success. They facilitated the structured integration and institutionalization of evidence-based sexual health curricula into the core program, and thus BPBR will be provided to all youth and young adults that enter Hartford Job Corps. This way, sexual health and pregnancy prevention information will remain foundational to the overall program, and trainees will have access to comprehensive information, as well as linkages to reproductive health services.

To date, HTPPI continues to provide training and technical assistance to Job Corps. These efforts will help ensure the institutionalization and sustainability of BPBR in the context of a comprehensive program designed to support economic development and improve the lives of vulnerable youth and young adults in Hartford.

Addressing the Comprehensive Needs of Young Men of Color: Alabama Department of Public Health (Mobile County Health Department) and the Mobile Kappa League

Research and policy efforts around teen pregnancy prevention have typically focused more on females than males (Scott, Steward-Streng, Manlove, & Moore, 2012). As a result, less is known about the best approaches to effectively engage young males in preventing teen pregnancy. Approximately 15% of males under 20 years of age fathered a child as reported by the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth, which showed distinct racial/ethnic disparities for Blacks (25%) and Hispanics (19%), compared to Whites (11%; Martinez, Chandra, Abma, Jones, & Mosher, 2006). These disparities underscore the need to use an SDOH approach to reduce teen pregnancy among young men of color. Addressing the social and contextual factors such as low educational achievement, lack of economic opportunity, and absence of support systems, including positive male role models, is especially pertinent to engaging young men in teen pregnancy prevention efforts (Bunting & McAuley, 2004; Covington, Peters, Sabia & Price, 2011; Marsiglio, Vastine, Sonenstein, Troccoli, & Whitehead, 2006; Pashcal, Lewis-Moss, & Hsiao, 2011; Teachman, 2004).

Among Alabama’s largest metropolitan statistical areas, Mobile County had the highest teen birth rate (36.1 per 1,000 females ages 15–19 years) in 2014 (Mobile County Health Department, 2016). As part of the CWI, the Alabama Department of Health, Mobile County Health Department’s ThinkTeen program aimed to increase the capacity of organizations to use best practices to decrease teen pregnancy through community engagement, health education, and public awareness within 13 zip codes with the highest teen birth rates in Mobile County.

In 2013 ThinkTeen convened representatives from the local school district, social services, and community-based agencies to participate in an RCA. The RCA identified young men’s lack of positive male role models and mentors in their communities, schools, and families as one of the root causes of teen pregnancy. As a result, ThinkTeen sought community-based organizations with mutual goals of motivating, educating, and empowering young men. The program ultimately partnered with the Mobile Kappa Developmental League Program (Kappa League), a program of the Mobile Alumni Chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc. The Kappa League provides mentoring and guidance to young men, emphasizing a holistic approach to development, including self-identity, discipline, academic achievement, career advancement, leadership and civic engagement, and health.

ThinkTeen and the Kappa League developed an implementation plan that began with cosponsoring community activities to support young male involvement in teen pregnancy prevention activities. These included a barbershop condom drop during prom season, in which young men were provided prevention information and condoms, and a “Brotherhood Night” focused on myths and facts about sexual health. In addition, ThinkTeen and the Kappa League hosted social events such as “Skate Night” where young men from both organizations distributed sexual health tip cards with links to further resources. ThinkTeen also coordinated an intergenerational discussion for males aged 15 to 19 years at a Male Summit in 2013. They openly discussed the lack of male engagement in teen pregnancy prevention efforts and identified key barriers similar to the RCA findings. They also echoed earlier findings about the absence of father figures and role models as a factor contributing to the community’s high rates of teen pregnancy. As the partnership evolved, the Kappa League became interested in integrating evidence-based programming into its mentoring program for high school–aged males. This resulted in the implementation of the Making Proud Choices (MPC) program by health educators from the Mobile County Health Department (one male and one female) with 80 young males in summer 2013 (http://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/oah-initiatives/tpp_program/db/programs/ebp-proud-choices.html). Based on unpublished data, preliminary posttest findings showed that young men who participated in MPC were less likely to report intentions to have sex in the next 3 months and more likely to go to a local clinic for birth control compared to baseline assessments. The young men also expressed appreciation for the program, stating, “It really opened my eyes a lot more about all the things that can come along with sex” and “My facilitator was very good and helped me understand things I didn’t know and helped better enhance the things I already knew.” Following the initial implementation, Kappa League advisors and other male mentors in the community completed training to implement MPC with young men. With the increase of male facilitators, ThinkTeen was able to connect young men in the community with positive role models to further foster teen pregnancy prevention efforts.

Thus, the collaboration between ThinkTeen and the Kappa League was successful at integrating pregnancy prevention programming into ongoing efforts to improve academic achievement, employment opportunities, and leadership development in young men. In addition, members of ThinkTeen and the Kappa League, including a youth representative presented on collaboration efforts to engage males more effectively in teen pregnancy prevention at the 2014 OAH Teen Pregnancy Prevention National Grantee conference. This presentation led to national coverage via the National Alumni Chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity’s website and an article in Huffington Post (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/laura-stepp/reduce-early-fathering-te_b_5495249.html).

While this partnership witnessed much success, challenges remain, including the lack of available slots for young men seeking to join the Kappa League’s activities. The Kappa League can serve only 80 young men during the program year, thus the majority of interested young males in Mobile County do not get the opportunity to participate. Yet ThinkTeen continues to spearhead efforts to enhance programming for young men by creating partnerships with other male serving organizations in Mobile County, such as 100 Black Men, which then provide further support systems for young men. MPC also continues to be implemented at the Kappa League, and trainings on mentoring are offered to other organizations serving young males in Mobile County. These efforts, along with other educational opportunities, will continue to address important gaps and needs of young men in Mobile County, not only to reduce teen pregnancy but also to rebuild the community one step at a time.

DISCUSSION

Establishing nontraditional partnerships with agencies that address SDOH can help vulnerable youth at increased risk for teen pregnancy and other adverse health outcomes. In addition, understanding how teen pregnancy is ultimately linked to many socioeconomic and social challenges can broaden our perspective and increase efforts to acknowledge and develop efforts to address the SDOH. As this approach gains momentum, we would be remiss if we did not discuss some of our early challenges. Many of the barriers we faced were related to the theoretical nature of SDOH work, which can be abstract and difficult to quantify. For some project partners, tackling SDOH seemed a monumental task they felt incapable of taking on, as SDOH were viewed as factors beyond the realm of teen pregnancy and not directly related to funded prevention efforts. However, with a systematic, structured approach, including heightened education and awareness of the root causes of teen pregnancy, the identification of specific SDOH to address based on community needs, and the engagement of nontraditional partners, state and community partners made substantial progress in implementing structural changes.

It is also important to note that forging nontraditional partnerships requires time and commitment, and developing partnerships that get at the root causes of teen pregnancy entails a great amount of innovation and flexibility. Through the project, we learned that special attention must be paid to ensure support from diverse community partners. Initially not all community agencies readily recognized their role in teen pregnancy prevention. This required demonstrating that because teen pregnancy is a complex and multilayered issue, each partner has a significant role to play in improving the health and well-being of adolescents in their communities. Framing teen pregnancy in a more comprehensive manner also helped some partners identify their specific roles. Moreover, creating a common vision and shared focus was critical since agencies have their own missions that may not include teen pregnancy prevention or adolescent health.

A key limitation of this work should also be highlighted. The examples shared are not generalizable to every community and only represent efforts undertaken by two communities out of the nine funded state- and community-based organizations. Since addressing the SDOH that affect teen pregnancy and forging non-traditional partnerships can be often complex and multidimensional, no two efforts will be exactly the same. To date both partnerships remain intact, yet future monitoring and evaluation related to the impact of such collaborations on teen pregnancy remain challenging. This is in part due to the lack of robust measurement tools related to SDOH and partnerships, as well as dependency on agency capacity and resources. However, it is hoped that youth serving professionals can glean practical information from these examples, which might better enable them to address SDOH at the community level. In addition, taking into consideration the needs of youth, agency capacity, as well as programmatic requirements will help ensure that all efforts are implemented with fidelity.

CONCLUSION

To support multilevel approaches to public health, multisectorial, nontraditional agencies coupled with evidence-based teen pregnancy and STI/HIV prevention program and reproductive health providers will offer more opportunities to expand efforts beyond the individual level to include interventions with population-wide impacts. Armed with this knowledge, public health professionals and youth serving organizations may be in a better position to effectively address the root causes of teen pregnancy and develop strategic plans to address related SDOH, while enhancing sustainability to reduce teen pregnancy, eliminate disparities, and improve the lives of vulnerable youth.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all the members of the Hartford Teen Pregnancy Prevention Initiative and the Mobile County Health Department’s ThinkTeen Pregnancy Prevention Program for their contributions to this article. We would also like to acknowledge Myriam H. Jennings of JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc., for her leadership on the Working with Diverse Communities component. This publication is made possible by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) through a partnership with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Adolescent Health. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC or HHS.

References

- Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Nontraditional collaborations and health equity. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.astho.org/t/pres_chal.aspx?id=6032.

- Bunting L, McAuley C. Research review: Teenage pregnancy and parenthood: The role of fathers. Child & Family Social Work. 2004;9:295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2004.00335.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson DL, McNulty TL, Bellair PE, Watts S. Neighborhoods and racial/ethnic disparities in adolescent sexual risk behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;43:1536–1549. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0052-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connecticut Women’s Education and Legal Fund. Continuous quality improvement report. Hartford, CT: Hartford Job Corps; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Covington R, Peters HE, Sabia JJ, Price JP. Teen fatherhood and educational attainment: Evidence from three cohorts of youth. 2011 Retrieved from http://resiliencelaw.org/word-press2011/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Teen-Fatherhood-and-Educational-Attainment.pdf.

- Cubbin C, Santelli J, Brindis CD, Braveman P. Neighborhood context and sexual behaviors among adolescents: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2005;37:125–134. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.125.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: The health impact pyramid. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;1:590–595. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold R, Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Lynch JW, Connell FA. Ecological analysis of teen birth rates: Association with community income and income inequality. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2001;5:161–167. doi: 10.1023/a:1011343817153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold R, Kennedy B, Connell F, Kawachi I. Teen births, income inequality, and social capital: Developing an understanding of the causal pathway. Health & Place. 2002;8:77–83. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8292(01)00027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK, Curtin SC, Mathews TJ. Births: Final data for 2014. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2015;64(12) Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_12.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartford Department of Health and Human Services. A community health needs assessment. 2012 Retrieved from http://hhs.hartford.gov/Shared%20Documents/Community%20health%20needs%20assessment%202012.pdf.

- Hartford Department of Health and Human Services. Final birth data 2013. Hartford, CT: Author; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc. Conducting a root cause analysis and action planning process: Facilitator’s guide. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.jsi.com/JSIInternet/Resources/publication/display.cfm?txtGeoArea=US&id=15191&thisSection=Resources.

- JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc. Broadening the base for teen pregnancy prevention: Expanding community partnerships & referral networks. 2014 Retrieved from http://rhey.jsi.com/files/2014/02/Partnership-Toolkit-Final.pdf.pdf.

- Maness SB, Buhi ER, Daley EM, Baldwin JA, Kromrey JD. Social determinants of health and adolescent pregnancy: An analysis from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;58:636–643. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglio W, Vastine AR, Sonenstein F, Troccoli K, Whitehead M. It’s a guy thing: Boys, young men, and teen pregnancy prevention. Washington, DC: The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez GM, Chandra A, Abma JC, Jones J, Mosher WD. Fertility, contraception, and fatherhood: Data on men and women from Cycle 6 (2002) of the National Survey of Family Growth. Vital and Health Statistics. 2006;23(26) Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_23/sr23_026.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobile County Health Department. Final birth data 2014. Mobile, AL: Author; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller T, Tevendale H, Fuller TR, House D, Romero L, Brittain A. Overview and lessons learned from implementing a multi-component, community-wide approach to teen pregnancy prevention in press. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. HealthyPeople 2020: Social determinants of health. n.d Retrieved from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=39.

- Pashcal AM, Lewis-Moss R, Hsiao T. Perceived fatherhood roles and parenting behaviors among African American teen fathers. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2011;26(1):61–83. [Google Scholar]

- Penman-Aguilar A, Carter M, Snead MC, Kourtis AP. Socioeconomic disadvantage as a social determinant of teen childbearing in the U.S. Public Health Reports. 2013;128(Suppl 1):5–22. doi: 10.1177/00333549131282S102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero L, Pazol K, Warner L, Cox S, Kroelinger C, Besera G, * Barfield W. Reduced disparities in birth rates among teens aged 15–19 years: United States, 2006–2007 and 2013–2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;65:409–414. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6516a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott ME, Steward-Streng NR, Manlove J, Moore KA. The characteristics and circumstances of teen fathers: At the birth of their first child and beyond. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Child_Trends-2012_06_01_RB_TeenFathers.

- Teachman JD. The childhood living arrangements of children and the characteristics of their marriages. Journal of Family Issues. 2004;25:86–111. [Google Scholar]

- Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, Marmot M, Resnick M, Fatusi A, Currie C. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. The Lancet. 2012;379:1641–1652. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]