Abstract

Adults implicitly judge people from certain social backgrounds as more “American” than others. This study tests the development of children's reasoning about nationality and social categories. Children across cultures (White and Korean American children in the U.S., Korean children in South Korea) judged the nationality of individuals varying in race and language. Across cultures, 5–6-year-old children (N=100) categorized English speakers as “American” and Korean speakers as “Korean” regardless of race, suggesting that young children prioritize language over race when thinking about nationality. Nine- and 10-year-olds (N=181) attended to language and race and their nationality judgments varied across cultures. These results suggest that associations between nationality and social category membership emerge early in life and are shaped by cultural context.

Keywords: Social cognition, cognitive development, national identity

Citizenship is typically defined by a set of objective rules. In the United States and many other nations worldwide, citizenship is conferred upon individuals based on determinants such as birthplace, parental citizenship, and specified naturalization processes. However, people do not necessarily think about nationality in exclusively objective terms. Instead, beliefs about national identity can be infiltrated by input about social category membership (e.g., a persons' racial or ethnic background or the language a person speaks) that falls outside the legal parameters for nationality. For instance, both historic and modern social science theories of nationalism eschew legal definitions of citizenship and instead identify participation in a common culture – often defined by sharing a common language – as the primary source of national group membership (Jay, 1787; Kohn, 1961; Kymlicka, 1999; Soysal, 1998).

Research from social psychology demonstrates that, when thinking about nationality, adults incorporate information implicitly that adults might not endorse explicitly. White American adults associate “American” with “White” (Devos & Banaji, 2005; Rydell, Hamilton, & Devos, 2010), even when considering well-known individuals, whose nationality is known to participants (e.g., Kate Winslet vs. Lucy Liu, Tony Blair vs. Barack Obama) (Devos & Ma, 2013; Devos & Ma, 2008). Perhaps more surprisingly, Asian American adults demonstrate this pattern as well (Devos & Banaji, 2005), suggesting the power of cultural messages to shape people's perspectives on their own national group membership. Yet, little is known about when these associations between nationality and social categories develop and how they are shaped by cultural context. The present research explores children's intuitive associations between language, race, and nationality across age and cultural groups.

Classic stage theories of cognitive development suggest that reasoning about nationality follows a protracted period of development. These early studies document noteworthy failures in children's early understanding (e.g., Jahoda, 1964; Piaget & Weil, 1951), perhaps due to the abstract nature of nationality. For instance, elementary school-aged children failed to understand that cities are spatially enclosed within nations (e.g., Geneva is geographically located inside of Switzerland) and have difficulty understanding that a person can hold more than one civic identity (e.g., a person who is Genevese is by definition also Swiss) (Jahoda, 1962; Piaget & Weil, 1951). Proposing that older children are more equipped to learn about abstract concepts than younger children (Jahoda, 1964), this account would predict that reasoning about nationality would unfold over time through explicit learning mechanisms, rather than intuitive reasoning. Because of this, young children may not have many reliable or systematic predictions about national group identity.

Developmental intergroup theory (Bigler & Liben, 2006) makes a different prediction. This theory argues that children can demonstrate positive attitudes towards a particular group before their conception of that group is fully developed. Children can attach salient social categories to explicit group labels even without fully understanding the nature of the category (Aboud, 1988; Hirschfeld, 1998). Their understanding of a group may still undergo revision and development, yet even their earliest understanding may map on to social groups in their environment (see Quintana, 1998, for a review). In this sense, even young children might hold intuitions about the link between nationality and social categories. They may recognize nationality as a meaningful social group, and derive a variety of stereotypes, associations, and inferences from that principle. In support of this possibility, although school-aged children sometimes cannot name countries besides their own, they already hold positive attitudes towards their own country (Barrett, 2013; Barrett, Wilson, & Lyons, 2003; Brown, 2011; Jahoda, 1962), and 8- to 11-year-old children can articulate that birthplace is an important feature in determining an individual's nationality (Carrington & Short, 1995).

An essentialist approach may similarly predict children's early social reasoning about nationality (Gelman, 2003; Gelman & DeJesus, in press). Essentialism shares many theoretical commonalities with developmental intergroup theory, as both perspectives would predict that children make inferences and hold stereotypes about individuals based on their social category membership (Gaither et al., 2014; Kinzler & DeJesus, 2013; Kinzler, Shutts, DeJesus, & Spelke, 2009). From an essentialist perspective, people's developing sense of social categories are often thought to reflect thinking about social kinds as stable, immutable, and objective. Yet, not all categories in the world are essentialized. Many factors may contribute to which categories are more likely to be essentialized, and several studies suggest that essentialism based on race may not emerge spontaneously in early childhood, but rather may follow a relatively protracted developmental trajectory (e.g., Rhodes & Gelman, 2009; Roberts & Gelman, 2016; Weisman, Johnson, & Shutts, 2015). These findings dovetail with evolutionary theory about social categorization, which asserts that race is a relatively new psychological phenomenon, in terms of human history (Kinzler, Shutts, & Correll, 2010; Kurzban, Tooby, & Cosmides, 2001; Lieberman, Oum, & Kurzban, 2008; Van Bavel & Cunningham, 2009). Prior to the onset of long distance migration, humans likely did not encounter individuals who looked very different. In this sense, race may not be a category that is intuitively seen as being an essential marker of social groups, in the absence of socialization experiences from society.

A similar research approach makes a different prediction about language: Language has marked human groups for a long time throughout human history (Cohen, 2012; Pietraszewski & Schwartz, 2014). Young children readily make inferences and social judgments based on others' language and accent (Kinzler & Dautel, 2012; Kinzler et al., 2009). A few studies provide suggestions that children may relate information about a person's language or accent to their nationality or geographic location (Carrington & Short, 1995; Kinzler & DeJesus, 2013; Weatherhead, White, & Friedman, 2016), but no research directly compares children's reasoning about different social categories (e.g., language, race) in guiding children's associations of national group membership. Moreover, priorities in children's associations may vary depending on their local context or their explorations of their own ethnic or racial identity (Phinney, 1989, 1993; Phinney & Tarver, 1988). For instance, among a group of children raised in the Basque Country in Spain, whether children were raised in Basque- or Spanish-speaking homes predicted whether they considered themselves to be “from Basque Country” or “from Spain,” as well as the attributes (either positive or negative) that children associated with each national group (Reizábal, Valencia, & Barrett, 2004). Thus, studying groups of children living in different social contexts is important to understand commonalities and differences in their reasoning about nationality, and how social categories may impact children's thinking.

The present research tests the developmental antecedents of people's reasoning about the link between nationality and social group membership. Studies of young children could reveal signatures of people's intuitive thinking about the meaning of national group membership, which may emerge early and guide the development of stereotypes and attitudes about others (Bigler & Liben, 2006). We hypothesize that even young children will demonstrate an association between nationality and social categories. Yet, that the nature of this association may prioritize language over race, and the development of intuitive reasoning about nationality will also be sensitive to cultural input. Though many nations have similar legal standards for determining citizenship (e.g., birthplace within territorial boundaries), experience within a culture may shape people's beliefs about what it means to be a member of their own national group. For instance, children may observe different relations between language, race, and nationality in their community (e.g., observing demographic diversity or homogeneity, hearing adults talk about nationality in different ways), which could in turn foster the development of different beliefs about nationality across cultures. As such, we hypothesize that specific patterns of reasoning about language, race, and nationality may be sensitive to cultural input, and therefore would be expected to differ in children from different cultural backgrounds.

To examine these questions, we asked children to categorize a series of individuals who varied in race (White or Asian) and language (English or Korean) as “American” or “Korean.” To assess potential priorities in children's associations between social categories (i.e., language and race) and nationality and how their thinking may differ across ages and cultural groups, we tested two age groups of children (5- and 6-year-old and 9- and 10-year-old children) who were recruited to participate from three populations: White American children in the United States, Korean American children in the United States, and Korean children in South Korea. We recruited these two age groups in light of past research demonstrating failures in children's early understanding of nationality (Jahoda, 1964; Piaget & Weil, 1951). One could hypothesize from this theoretical framework that 5- and 6-year-old children may have no systematic expectations about the relation between nationality and social group membership and this reasoning may not emerge until later in development. Instead, we hypothesize that children may view nationality as related to social categories from an early age, and specifically that children would prioritize language over race in their nationality judgments, particularly in early childhood (Kinzler & Dautel, 2012; Kinzler et al., 2009). By varying the race and language of the individuals presented and by testing child participants of different ages and in different cultural groups, we were able to explore children's early-developing, intuitive associations about national group membership and the development of these beliefs in different cultural contexts.

Methodological Approach

Nationality is a broad construct that has been examined using many different methods. Previous research on adults' and children's reasoning about nationality includes ethnographic work, theories developed by historians and political scientists, survey methods, and studies of implicit attitudes. These diverse methods have contributed to the perspective that nationality is more than a set of legal criteria, and rather is a powerful social construct. In the present research, we follow from approaches developed by social psychologists, who have found that adults implicitly associate nationality with social category membership (e.g., they more easily associate White faces with American symbols), even when they explicitly state that people across social categories should be treated equally as Americans (Devos & Banaji, 2005). Simply viewing a face revealed an intuitive connection with national group membership. Children may also have early intuitions about the social nature of nationality that could be measured in a controlled and paired down task. In the present research, we utilized a simple method to assess young children's quick categorizations of the nationality of a series of individuals after they viewed each person's face and heard their voice. Each individual was either White or Asian and spoke in English, Korean, French, or Korean-accented English. Children were simply asked whether each person was American or Korean. Though this method does not test all constructs or ways of thinking about nationality (we return to limitations of our method in the general discussion), this method does provide insight into children's quick thinking about social groups. Moreover, a key strength of this simple design is that the same method can be implemented across age groups (5- and 6-year-olds, 9- and 10-year-olds) and cultural contexts.

Experiment 1: White American children in the United States

Experiment 1 tested 5- and 6-year-old and 9- and 10-year-old White American children's reasoning about the relation between language, race, and nationality. Children were shown a series of individuals varying in race and language and were asked to categorize them as “American” or “Korean.” It is possible that associations between language, race, and nationality may not develop until later in childhood, especially in light of research documenting children's early failures to understand nationality (e.g., Jahoda, 1964; Piaget & Weil, 1951). Alternatively, if children view nationality as a social identity, then associations between social group membership and national group membership may emerge early in life. As such, we might expect children's associations between nationality and social group membership to come online during a similar time period as children's documented social preferences for individuals who are members of their own group (e.g., Kinzler et al., 2009). According to this hypothesis, we would expect 5- and 6-year-olds and 9- and 10-year-olds to demonstrate similar signatures of reasoning about nationality.

Method

Participants

Participants in Experiment 1 were White monolingual English-speaking children in the greater Chicago area and were recruited from a volunteer database to participate in a laboratory study. Two age groups were tested: 5–6-year-olds (N = 16, 8 female, 8 male; M = 5.98 years, SD = 0.54 years, range = 5.32 – 6.77 years) and 9–10-year-olds (N = 16, 9 female, 7 male; M = 9.65 years, SD = 0.56 years, range = 9.04 – 10.54 years). Children lived in the Midwestern United States. The sample sizes recruited for each age group were planned based on the sample sizes in related past studies with children (Baron & Banaji, 2006; Byers-Heinlein & Garcia, 2015; Kinzler et al., 2009; Rhodes & Gelman, 2009), with consideration to the number of participants required to fully counterbalance the design of the stimuli. Parents provided written informed consent for their children to participate and completed demographic questionnaires; children provided verbal assent. Children participated in this study in 2009 and 2010.

Context

Chicago is a large, racially diverse city: According to the 2010 Census, the population was approximately 2.7 million and the racial makeup of the city was 45.3% White (31.7% non-Hispanic White), 32% Black or African American, 5% Asian, and 3% for more than one racial group (United States Census Bureau, 2010a). Chicago has the fifth highest population of foreign-born residents in the United States (21.7% in 2000; of this, 18.0% was born in Asia), and as of the 2000 U.S. Census there were approximately 45,000 people of South Korean-origin living in the Chicago metro area (United States Census Bureau, 2000). Approximately 30% of Chicago-area residents speak a language other than English at home, with the five most common languages being Spanish, Polish, Arabic, Tagalog, and Chinese.

Procedure

Children viewed 16 targets varying in race and language and were asked to judge each individual's national group membership. On each trial, children viewed one face and listened to an accompanying voice clip on a laptop computer. Faces were photographs of White or Asian adults (Asian adults were ethnically Korean). We refer to these faces as “Asian” throughout to clearly distinguish between Korean faces and Korean language when presenting the results, but all faces were ethnically Korean.

Voice clips were neutral child-friendly statements (e.g., “people can go swimming during the summer”) recorded by adults who spoke in English, Korean, French, and Korean-accented English. We included French to provide a language that would be equally unfamiliar to all children across populations, given that subsequent studies test monolingual Korean-speaking children and bilingual speakers of Korean and English. For each individual, children were asked, “Do you think [she or he] is American or Korean?” (order of “American” and “Korean” was counterbalanced across participants). Children saw all eight possible combinations of race and language twice (one male, one female) across the 16 trials (target gender, race, and language were counterbalanced within and across participants).

Results

To test whether children systematically categorized speakers of particular languages or members of particular racial groups as either “American” or “Korean,” binomial tests were performed for each trial type to assess whether children were more likely to categorize targets as “American” or “Korean” than would be expected by chance (for additional studies that employ binomial tests, see Corriveau, Kinzler, & Harris, 2013; Rhodes, Gelman, & Karuza, 2014; VanderBorght & Jaswal, 2009). For ease of comparison, all means are presented as the proportion of trials in which children judged targets as “American.” Proportions closer to 1 indicate that children categorized targets as “American,” whereas proportions closer to 0 indicate that children categorized targets as “Korean.”

To compare across trials, we calculated 95% confidence intervals for each trial type (see Table 1). Confidence intervals that do not overlap are considered to be significantly different from each other; confidence intervals that do overlap are not considered to be significantly different. We selected 95% confidence intervals throughout as a conservative test of our hypothesis, but because we had directional predictions and to give a more thorough description of the data, we also note the few instances in which confidence intervals did not overlap at the 90% level (4 out of the 24 sets of confidence intervals). Standard deviations are provided alongside the proportions to provide additional context and connection to the calculation of the confidence intervals.

Table 1. Proportion of “American” categorizations by trial type, population, and age group.

| Five- and 6-year-old children | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Exp. 1: M (CI) | Exp. 2: M (CI) | Exp. 3: M (CI) |

| White-English | .94* (.85, 1.00) | .91* (.80, 1.00) | .96* (.91, 1.00) |

| Asian-English | .91* (.76, 1.00) | .72* (.50, .94) | .86* (.78, .94) |

| White-Korean | .09* (.00, .24) | .22* (.00, .44) | .15* (07, .24) |

| Asian-Korean | .16* (.00, .34) | .03* (.00, .10) | .02* (.00, .05) |

| White-KAE | .31* (.10, .53) | .75* (.56, .94) | .93* (.89, .97) |

| Asian-KAE | .19* (.05, .32) | .47 (.30, .76) | .85* (.77, .92) |

| White-French | .09* (.00, .20) | .84* (.68, 1.00) | .97* (.94, 1.00) |

| Asian-French | .03* (.00, .10) | .53 (.30, .76) | .88* (.80, .95) |

| Nine- and 10-year-old children | |||

| Trial | Exp. 1: M (CI) | Exp. 2: M (CI) | Exp. 3: M (CI) |

| White-English | 1.0* (1.00, 1.00) | .91* (.76, 1.00) | .97* (.95, .99) |

| Asian-English | .72* (.48, .96) | .59 (.42, .77) | .43 (.36, .50) |

| White-Korean | .31* (.08, .55) | .31* (.08, .55) | .58* (.52, .65) |

| Asian-Korean | .03* (.00, .10) | .09* (.00, .24) | .15* (.11, .20) |

| White-KAE | .63 (.38, .87) | .44 (.20, .67) | .66* (.59, .72) |

| Asian-KAE | .16* (.00, .32) | .19* (.02, .35) | .20* (.14, .25) |

| White-French | .50 (.26, .74) | .75* (.58, .92) | .90* (.86, .94) |

| Asian-French | .03* (.00, .10) | .41 (.21, .61) | .54 (.48, .60) |

Note. Proportions that are significant at p < .05 are marked with asterisks. “KAE” stands for Korean-accented English.

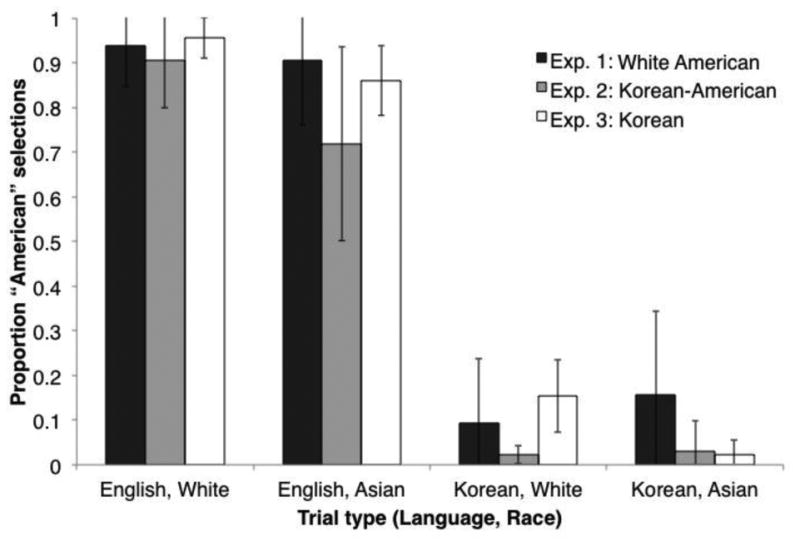

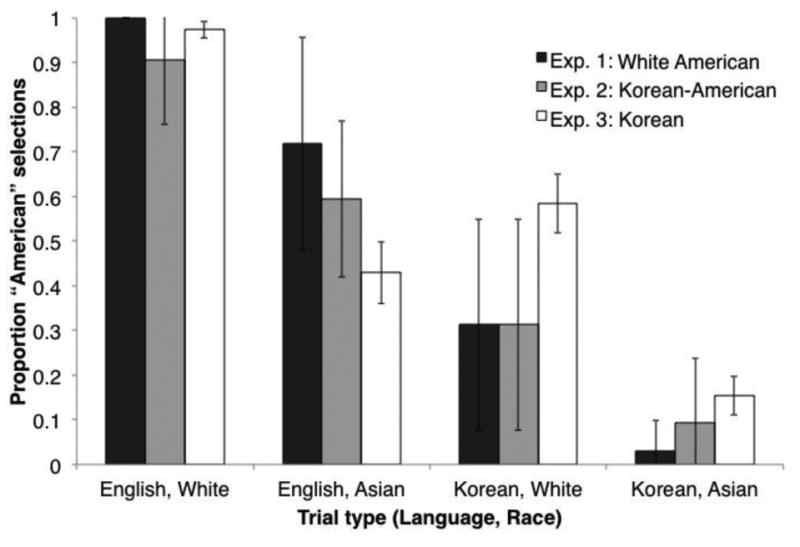

We were especially interested in children's responses in trials featuring native English and Korean speakers, so those trials are featured in Figures 1 and 2. We include results for all trial types, divided by age group and population, in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Responses of 5- and 6-year-old children by population for trials featuring native English and Korean speakers. Black lines show 95% confidence intervals. See Table 1 (top) for data from all trials.

Figure 2.

Responses of 9- and 10-year-old children by population for trials featuring native English and Korean speakers. Black lines show 95% confidence intervals. See Table 1 (bottom) for data from all trials.

White American 5- and 6-year-old children

White American 5- and 6-year-old children categorized people who spoke English as “American” and people who spoke Korean as “Korean,” regardless of the race of the target presented (English: MWhite = .94, SD = .17, MAsian = .91, SD = .27; Korean: MWhite = .09, SD = .27, MAsian = .16, SD = .35; ps < .001; see Figure 1, left bars).

When considering targets who spoke in French or Korean-accented English, children categorized these speakers as Korean (i.e., not American), regardless of each target's racial group membership (French: MWhite = .09, SD = .20, MAsian = .03, SD = .13; ps < .001; Korean-accented English: MWhite = .31, SD = .40, MAsian = .19, SD = .25; ps < .05; see Figure 1, right bars). Taken together, these results reveal that White American children only categorized targets who spoke English with an American accent as American. Children categorized individuals who spoke in Korean, French, or Korean-accented English as members of a different national group, and this was the case when evaluating both White and Asian faces.

These results provide evidence that young children considered language, but not race, when making judgments about nationality. To provide a further test of this idea, we compared the 95% confidence intervals for individuals presented as White or Asian for each language. To give an example, if the confidence intervals overlap for children's reasoning about English speakers who were presented as either White or Asian, then this pattern would suggest that children did not significantly consider race in their judgments. If the confidence intervals do not overlap, then this pattern would suggest that children are considering race, even though targets were nonetheless reliably categorized as “American.” For each presented language, the confidence intervals did overlap, suggesting that children did not differ in their categorizations of White and Asian targets for any language (see Table 1).

White American 9- and 10-year-old children

Older White American children also reported that people who spoke English were “American” and people who spoke Korean were “Korean,” and this pattern held when evaluating both White and Asian targets (English: MWhite = 1.00, SD = .00, p < .001, MAsian = .72, SD = .45, p = .02; Korean: MWhite = .31, SD = .44, p = .05, MAsian = .03, SD = .13, p < .001; see Figure 2, left bars). Thus, older children, like younger children, categorized faces reliably based on the language they spoke.

When considering targets who spoke French or Korean-accented English, older children's categorizations reflected evidence of attention to race. Children did not reliably categorize French or Korean-accented English speakers as either “American” or “Korean” if targets were presented as White (French: MWhite = .50, SD = .45, p > .9; Korean-accented English: MWhite = .63, SD = .47, p = .22), whereas they categorized French or Korean-accented English speakers as Korean if targets were presented as Asian (French: MAsian = .03, SD = .13, p < .001; Korean-accented English: MAsian = .16, SD = .30, p < .001).

Comparisons of confidence intervals across trials also revealed children's attention to both language and race when judging nationality (see Table 1 for data). As described above, children reliably classified both White and Asian targets as “American” when they spoke English and “Korean” when the spoke Korean, suggesting robust attention to language. Yet, when comparing categorizations of English-speakers, children were more likely to choose “American” for White than for Asian targets, suggesting a subtle attention to race. Children demonstrated a similar pattern when evaluating Korean speakers, whereby children were more likely to choose “Korean” for Asian than White targets at the 90% level (suggesting marginal significance). Furthermore, children were more likely to classify French and Korean-accented English speakers as “American” if presented as White than if presented as Asian. Together, these results suggest that older children considered both language and race when thinking about nationality. Overall, children categorized English speakers as American and Korean speakers as Korean regardless of race, yet within a given language category, White targets were more likely to be classified as American than Asian targets.

To rule out the possibility that children prioritized language over race because they were not able to perceptually differentiate between the presented faces, we asked a separate group of 44 monolingual English-speaking children (26 female, 18 male; M = 7.04 years, SD = 1.90 years, range = 4.10 – 11.25 years; 27 White, 16 African American, 1 biracial White and African American) in the greater Chicago area to categorize the same targets used in Experiment 1 by race, without providing any language information or racial labels. In one sequential computerized task and one card sort task, in which children could see the full set of faces, we asked children to sort the faces based on which faces looked alike. Children were significantly more likely to match White faces with White faces and Asian faces with Asian faces than would be expected by chance on both the computerized task (M = 90.7%, SD = 2.40), t(43) = 17.0, p < .001, and the card sort task (M = 93.4%, SD = 1.83), t(43) = 23.7, p < .001. Age was not correlated with children's performance on either task (computer: r(44) = 0.19, p = .221; card sort: r(44) = 0.01, p = .955).

Discussion

The results of Experiment 1 revealed two important findings. First, White American 5- and 6-year-old children prioritized language over race when making judgments about others' national group membership. Children categorized both White and Asian people as American if they spoke English, whereas they categorized people who spoke in any other unfamiliar language or accent (Korean, French, Korean-accented English) as Korean. These results suggest that the association ‘American = English-speaker’ emerges before the association ‘American = White,’ even though children across ages were able to categorize the faces in this stimuli set based on race, and build on past studies showing that language robustly guides young children's social judgments (e.g., Kinzler & DeJesus, 2013; Kinzler et al., 2009; Souza, Byers-Heinlein, & Poulin-Dubois, 2013).

Second, children's attention to race when making judgments about nationality differed across age groups. Whereas both age groups demonstrated a significant influence of language on their judgments, a more subtle attention to race nonetheless guided older children's decisions about nationality. Thus, the association between nationality and race documented in adults (Devos & Banaji, 2005; Devos & Ma, 2013; Devos & Ma, 2008) appears to emerge by middle childhood and may not require adult-like experiences and knowledge about national groups.

Though these results reveal an early-emerging link between children's thinking about social identities and nationality, it is unclear from these results what role cultural context might play in shaping children's reasoning about nationality. One possibility is that the associations we observed between children's thinking about language, race, and nationality may be highly constrained by their local cultural context. The children we tested were all White, monolingual speakers of English. Though they live in a diverse city with a relatively large population of foreign-born residents and people who speak languages other than English, parents reported that the participants tested here did not have regular exposure to people who speak other languages, which may have important implications for participants' association between speaking English and being American. Exposure to additional linguistic diversity, including speaking multiple languages oneself, may lead to more flexible thinking about national group membership, particularly in light of past studies that show greater social and cognitive flexibility among children with diverse language experiences (Adi-Japha, Berberich-Artzi, & Libnawi, 2010; Fan, Liberman, Keysar, & Kinzler, 2015; Kovács & Mehler, 2009a, 2009b). Therefore, we might therefore expect American children in bilingual contexts to have less rigid views about the link between being an English-speaker and being an American.

Alternatively, children across cultural contexts may consider “English-speaking” as indicative of being “American” early in development. Children's exposure to people who speak in different languages, people from different racial or ethnic backgrounds, and people who were born in different countries can vary, yet children with different experiences may nonetheless converge on consistent associations between nationality and social category membership. In support of this possibility, research with adults suggests that the association ‘White = American’ persists across both White American and Asian American adults (Devos & Banaji, 2005).

To test the generalizability of our findings from Experiment 1 to different populations of American children, Korean American children were recruited to participate in Experiment 2. Participants were all ethnically Korean and spoke both English and Korean. They were also regularly exposed to Americans who are White and who are Asian, and to speakers of both English and Korean. Their parents were all born in South Korea and immigrated to the United States.

Experiment 2: Korean American children in the United States

As in Experiment 1, Korean American children tested in Experiment 2 consisted of two age groups (5- and 6-year-olds; 9- and 10-year-olds). They completed the same task as children in Experiment 2.

Method

Participants

All participants in Experiment 2 were Korean American children who were bilingual speakers of Korean and English and had parents who were born in Korea and immigrated to the United States. We tested 5- and 6-year-olds (N = 16, 8 female, 8 male; M = 5.91 years, SD = 0.59 years, range = 5.08 – 6.83 years) and 9- and 10-year-olds (N = 16, 8 female, 8 male; M = 9.76 years, SD = 0.53 years, range = 9.00 – 10.50 years). Children lived in the Midwestern United States. Children were recruited from Korean language schools and Sunday schools in ethnically Korean churches in the areas. Children participated in this study in 2009 and 2010.

Most participants (28 out of 32) were born in the U.S. (4 were born in South Korea), and all participants had two parents who were born in South Korea. When asked to report children's native language, 17 parents listed both Korean and English, 13 listed only Korean, and 2 listed only English. Children's proficiency in both languages varied (from basic proficiency to native speaker), as did the amount of time parents estimated that children hear each language (e.g., English 10%, Korean 90%; English 50%, Korean 50%; English 80%, Korean 20%). Additionally, many parents (17 out of 19 for which we have data) sought additional tutoring in Korean for their children, as children in this sample attend English-language schools.

As in Experiment 1, we planned this sample size based on previous related research (Baron & Banaji, 2006; Byers-Heinlein & Garcia, 2015; Kinzler et al., 2009; Rhodes & Gelman, 2009) and requirements for counterbalancing. Parents provided written informed consent for their children to participate and completed demographic questionnaires; children provided verbal assent. Parents were provided with consent forms and questionnaires written in English and Korean; most parents (29 out of 32) elected to complete forms written in Korean.

Context

Children were recruited from the greater Chicago, IL, and Columbus, OH, areas. As noted above, approximately 45,000 people of South Korean-origin were living in the Chicago metro area as of the 2000 Census (United States Census Bureau, 2000) and 5% of Chicago's population of approximately 2.7 million was Asian as of the 2010 Census (United States Census Bureau, 2010a). An additional location was sought to increase our ability to recruit Korean American participants. According to the 2010 Census, Columbus has a population of approximately 790,000 and the racial makeup of Columbus was 62% White (59% non-Hispanic white), 28% Black or African American, 4% Asian, and 3% for more than one racial group (United States Census Bureau, 2010b). Korean families in this sample tended to live in suburban areas and attend Korean churches for weekly cultural interactions. Children in this sample were recruited from Korean churches and Sunday schools, where they regularly interact with other Korean American families in their community.

Procedure

Korean American children were tested using the same stimuli, design, and procedure as in Experiment 1. All children were tested by a Korean American experimenter who was a bilingual speaker of Korean and English. Half of the participants were tested in English (N = 17) and half were tested in Korean (N = 15). We tested children in different languages based on past findings that bilingual adults demonstrate more positive implicit attitudes towards the language in which they are tested (Danziger & Ward, 2010; Ogunnaike, Dunham, & Banaji, 2010). However, initial analyses revealed no systematic influence of test language on Korean American children's responses (A chi-square found no significant effect of test language on children's responses by trial type, χ2 (df = 7) = 2.97, p = .89), so we collapsed across test language in the following results.

Results

As in Experiment 1, Korean American children's responses were analyzed using binomial tests for each trial type and confidence intervals to compare across trial types.

Korean American 5- and 6-year-old children

An analysis of each trial type revealed that bicultural children also prioritized language when making nationality judgments. Younger Korean American children categorized people who spoke English as “American” and people who spoke Korean as “Korean,” and this was the case for both White and for Asian targets (English: MWhite = .91, SD = .20, p < .001, MAsian = .72, SD = .41, p = .02; Korean: MWhite = .22, SD = .41, p = .002, MAsian = .03, SD = .13, p < .001; see Figure 1, center bars). Thus, as in Experiment 1, children categorized the nationality of targets based on language. When considering targets who spoke in French or Korean-accented English, children categorized targets who appeared White as “American” (French: MWhite = .84, SD = .30; Korean-accented English: MWhite = .75, SD = .37; ps < .007), but were at chance when categorizing targets who were presented as Asian (French: MAsian = .53, SD = .43; Korean-accented English: MAsian = .47, SD = .43; ps > .5).

Comparisons across trial types revealed that, similar to White American children, Korean American children relied primarily on language to determine an individual's nationality. For each presented language, the confidence intervals overlap, suggesting that children did not reliably differ in their categorizations of White and Asian targets for any language (see Table 1).

Korean American 9- and 10-year-old children

Older Korean American children categorized English-speaking targets as “American” if targets were presented as White (MWhite = .91, SD = .27, p < .001) but they did not reliably categorize English-speaking targets who were Asian as “American” or “Korean” (MAsian = .59, SD = .33, p = .38). Children categorized Korean speakers as “Korean” for both White and Asian targets (MWhite = .31, SD = .44, p = .05; MAsian = .09, SD = .27, p < .001; see Figure 2, center bars).

When considering targets who spoke in French or Korean-accented English, older children reported that targets who spoke French were “American” if presented as White (MWhite = .75, SD = .32, p = .007) but they did not reliably categorize French-speakers who were presented as Asian (MAsian = .41, SD = .38, p > .4). Targets who spoke English with a Korean accent were categorized as “Korean” if Asian (MAsian = .19, SD = .31, p < .001) but participants did not reliably categorize White Korean-accented English-speaking targets (MWhite = .44, SD = .44, p > .4). These analyses suggest that older Korean American children may have incorporated race into their nationality judgments, yet they also did not reliably categorize many of the presented individuals. This uncertainty may demonstrate greater consideration of multiple pieces of information (i.e., language and race) but is difficult to interpret because children's responses were variable and not significantly different from chance. Indeed, comparing across trial types did not reveal evidence of significantly different categorizations for White and Asian targets, since 95% confidence intervals for White and Asian targets overlapped. An analysis of the 90% confidence intervals, however, demonstrated a marginal influence of target race on participants' categorization for English- and Korean-speaking targets, whereby when considering the same language, children were more likely to categorize White targets as “American” than Asian targets (90% confidence intervals for French and Korean-accented English-speaking targets overlapped).

Discussion

The results of Experiment 2 revealed two main findings. First, Korean American 5- and 6-year-old children prioritized language over race. Specifically, younger Korean American children categorized English speakers as American and Korean speakers as Korean, regardless of the race of the target. These results provide further evidence for the association ‘American = English-speaker,’ even in a population of children who speak Korean themselves and have extensive exposure to Asian and Korean-speaking people who live in the United States. Second, older Korean American children demonstrated some attention to both language and race in their judgments. For instance, older children categorized Korean-speaking targets as Korean regardless of race, but only categorized White English-speaking targets as American. Their responses did not differ from chance when evaluating Asian English-speaking targets. Thus, children's thinking about the link between race and nationality, as is evident in adults (e.g., Devos & Banaji, 2005; Devos & Ma, 2013; Devos & Ma, 2008), is likely coming online by middle childhood. Moreover, just as White and Asian American adults similarly demonstrated associations between race and nationality, White and Korean American children in the United States demonstrated similar thinking about associations between nationality and social categories (Devos & Banaji, 2005).

Taken together, these results are largely similar to the findings of Experiment 1, which included White American children. Despite the many differences in the social experiences of these two populations of children, including language exposure and racial and cultural background, both populations demonstrated early attention to language when reasoning about nationality and emerging attention to race among older children. These results provide evidence that children living in different cultural contexts in the United States may hold similar associations between social group membership and national group membership early in childhood.

The children tested in Experiments 1 and 2 all lived in the United States. Children in many different American contexts may receive similar cultural input about national group membership and what it means to be American in school or through popular English-language media. For instance, observing news media influences the formation of children's political attitudes and national identities (Conway, Wyckoff, Feldbaum, & Ahern, 1981; Slavtcheva-Petkova, 2013; Toivonen & Cullingford, 1997). Consequently, it is important to understand how children living outside the United States, who may have different cultural input and experiences with linguistic, ethnic, and racial diversity compared to children living in the United States, may come to hold different beliefs about nationality. Through cross-cultural comparisons, we can investigate which intuitive aspects of thinking about national groups are similar across cultures and which are constrained by a child's local environment. To begin to test this hypothesis, children living in South Korea were recruited to participate in Experiment 3. South Korea is relatively linguistically, racially, and ethnically homogenous (Central Intelligence Agency, 2015). We were again interested in how children's beliefs about nationality initially form, and how they might be shaped by cultural experience.

Experiment 3: Korean children in South Korea

In Experiment 3, we presented Korean children in South Korea with the same task presented to American children in Experiments 1 and 2.

Method

Participants

Participants in Experiment 3 included Asian monolingual Korean-speaking 5- and 6-year-old children (N = 68, 34 female, 34 male; M = 6.01 years, SD = 0.5 years, range = 5.11 – 6.89 years) and 9- and 10-year-old children (N = 149, 76 female, 73 male; M = 9.89 years, SD = 0.5 years, range = 9.03 – 10.92 years). All parents reported their child's ethnicity as Korean (with two exceptions: 1 parent did not report; 1 parent reported the child's ethnicity as both Korean and Japanese). Children lived in South Korea and were recruited from schools in Seoul, South Korea. They all spoke Korean as their first language, and had limited exposure to English in school. Although we planned to include the same sample sizes as in the first two experiments, more parents gave permission for their children to participate than anticipated and the participating schools requested that all children be tested. Thus, we include all data collected here. Parents provided written informed consent for their children to participate and completed demographic questionnaires (forms were distributed and collected at school); children provided verbal assent. Children participated in this study in 2010.

Context

Seoul, South Korea is a large city, with a population of 9.74 million and is one of the world's most densely populated cities (Central Intelligence Agency, 2016; “Foreign population,” 2010). The vast majority of Seoul residents are ethnically Korean, with small Chinese (approximately 187,000 people) and American populations (approximately 10,000 people). Korean is the official language of South Korea (Central Intelligence Agency, 2016). English is often taught in schools by native English speakers born outside of Korea (Shin-Wo, 2009).

Procedure

The materials, procedure, and design were identical to Experiments 1 and 2. All children were tested in Korean. Younger children were each tested individually as in the first two experiments. At the request of the participating school, older children were tested simultaneously in their classrooms. For older children, face stimuli were projected on to a screen that could be viewed by the entire class while the experimenter played the corresponding audio stimuli. Children recorded their responses silently using pencil and paper. Each classroom viewed a different trial order, but the same stimuli, counterbalancing, and experimenter instructions were used as in Experiments 1 and 2. Children circled “American” or “Korean” on a coding form; half of participants received a form with “American” written on the left and “Korean” written on the right and half received the opposite layout.

Results

As in Experiments 1 and 2, children's responses were analyzed using binomial tests for each trial type and confidence intervals to compare across trial types.

Korean 5- and 6-year-old children

As in the United States, 5- and 6-year-old children in South Korea used information about language to make judgments about nationality. Children categorized targets who spoke English as “American” (MWhite = .96, SD = .19, p < .001; MAsian = .86, SD = .32, p < .001) and targets who spoke Korean as “Korean” (MWhite = .15, SD = .34, p < .001; MAsian = .02, SD = .13, p < .001 for both White and Asian targets.

Targets who spoke in French and Korean-accented English were all categorized as “American,” rather than “Korean” (French: MWhite = .97, SD = .12, MAsian = .88, SD =.29; Korean-accented English: MWhite = .93, SD = .20, MAsian = .85, SD = .33; all ps < .001), and this was true for both Asian and for White targets (see Figure 1, right bars).

Comparing across trial types, younger Korean children's categorizations largely did not differ based on race, with two notable exceptions. First, younger Korean children were more likely to categorize Asian targets who spoke Korean as “Korean” than White targets who spoke Korean (95% confidence intervals did not overlap). Second, younger Korean children were marginally more likely to categorize Asian French-speaking targets as “Korean” than White French-speaking targets (90% confidence intervals did not overlap).

Korean 9- and 10-year-old children

Older children tested in South Korea primarily used race, not language, when making nationality judgments. Children categorized English-speaking targets as “American” when presented as White (MWhite = .97, SD = .11, p < .001), but as Korean when presented as Asian (MAsian = .43, SD = .43, p = .06). Similarly, children categorized targets who spoke Korean as “Korean” if presented as Asian (MAsian = .15, SD = .27, p < .001) but as “American” if presented as White (MWhite = .58, SD = .40, p = .005).

Participants also used race to differentiate between French and Korean-accented English speakers. Children categorized targets who spoke in French as “American” if they were presented as White (MWhite = .90, SD = .25, p < .001), but not if they were presented as Asian (MAsian = .54, SD = .37, p = .18). Children categorized targets who spoke in English with a Korean accent as American if White (MWhite = .66, SD = .40, p < .001) and Korean if Asian (MAsian = .20, SD = .33, p < .001; see Figure 2, right bars).

Comparing across trials, children's responses reflected attention to race when judging nationality (as evidenced by non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals, see Table 1). Within the same language, children differentially responded when the face was presented as White versus Asian.

Discussion

Korean children tested in Experiment 3 demonstrated different patterns of associations between nationality and social groups at different points in development. Five- and 6-year-old children in South Korea robustly used language when evaluating another person's nationality. Similar to 5- and 6-year-old children in Experiments 1 and 2, younger Korean children tested in Experiment 3 categorized English-speaking targets as American and Korean speakers as Korean. Yet, 9- and 10-year-old children in South Korea prioritized race over language and rated White targets as American and Asian targets as Korean for most trials. Nine- and 10-year-old children across cultural contexts demonstrated some attention to both language and race in their nationality judgments, yet the relative weighing of these categories followed different patterns: Older children in the United States (White American and Korean American) demonstrated attention to both language and race in their nationality judgments, whereas older children tested in South Korea prioritized race over language. Taken together, these results suggest that children in South Korea may develop a different perspective on the social meaning of nationality compared to children living in the United States during the early school years, though children's early intuitions about nationality may initially be similar across cultural contexts.

General Discussion

The studies presented here reveal two key findings. First, young children's early reasoning about national group membership is guided by information about social categories, and children associate language with national identity early in life. We observed remarkable similarities among 5- and 6-year-old children tested across cultural contexts, including White American and Korean American children tested in the United States and Korean children tested in South Korea. Specifically, children categorized English-speaking targets as American and Korean-speaking targets as Korean, regardless of the presented race of each target (White vs. Asian). In contrast to classic theories of development asserting that children do not have a conceptual understanding of nationality (e.g., Jahoda, 1964; Piaget & Weil, 1951), the present research demonstrates that children reliably associate social group membership with national groups (see Van Deth, Abendschön, & Vollmar, 2011, for a related discussion of children's early political attitudes). These findings support the argument that implicit social biases emerge early in life and do not require protracted experience or knowledge to develop, consistent with predictions from developmental intergroup theory (Bigler & Liben, 2006). In addition, young children's prioritization of language over race when making judgments about nationality is consistent with an essentialist approach (Gelman, 2003; Gelman & DeJesus, in press). Before children have detailed knowledge of the determinants of nationality, they use information about social groups, specifically language, to understand national groups as a category. These findings are consistent with previous research that children use language more than race in their social judgments (Kinzler & Dautel, 2012; Kinzler et al., 2009), evolutionary perspectives on the meaning of language and race throughout human history (Cohen, 2012; Kinzler et al., 2010; Kurzban et al., 2001; Pietraszewski & Schwartz, 2014), and sociological and political science theories of the role of language in establishing a common culture (Jay, 1787; Kohn, 1961; Kymlicka, 1999; Soysal, 1998). Although young children may not have extensive experience reasoning explicitly about nationality, they already hold an association between nationality and social group membership.

Second, by age 9 children incorporate race into their judgments about nationality, and the extent to which they do so differs across cultural contexts. In all three populations tested, older children demonstrated some increased attention to race in their nationality judgments. This was particularly the case among older children tested in South Korea, as they primarily used race, not language, when making nationality judgments. Additional studies in different types of homogenous and heterogeneous environments would be informative to understand how one's local context might shape priorities in reasoning about social categories. Taken together, these findings suggest that although children's reasoning about nationality may be initially similar across cultural contexts, older children demonstrate different attitudes, both from younger children and across cultures, and early social environments may play an important role in the development of children's reasoning about national groups. Future studies would benefit from a direct investigation of how children begin to incorporate multiple cues to national group membership in their judgments. As we mention in Experiment 2, differentiating between incorporating multiple pieces of information and general uncertainty is difficult in this design. Having children use a scale to rate an individual's national group membership, rather than a forced choice measure, could provide additional evidence regarding how children rank different cues to national group membership (e.g., language, birthplace, current location).

This study offers an important first step in understanding children's beliefs about nationality, but has several limitations that would benefit from future investigation. First, methods that provide children with a wider variety of response options (e.g., a scale rather than a forced-choice question) could provide insight into whether children believe that a person can be a member of more than one national group simultaneously or how categorizing a person as “American” might differ from categorizing a person as “not Korean.” As described in our methodological approach, the simple design of the present research is critical to understand potential differences across age groups and cultural contexts by employing the same stimuli, however methods inspired by ethnographic, survey, or historical research may provide additional insights into the process of children's reasoning about nationality. Second, it is possible that administering the task at the group level for older children, rather than individually, may meaningfully influence children's responses in this task. Though we know of no prior studies that would provide a mechanism for this method to lead to greater consideration of race, we cannot directly rule out this possibility. Finally, these results may be limited to the specific populations that were tested and the stimuli that were developed for the present study. Children from different cultural backgrounds, evaluating more diverse stimuli, would be informative to draw broader conclusions about the development of children's thinking about nationality.

What types of input may impact children's beliefs about national group membership and contribute to the observed divergence in older children's responses across communities? One possibility is that formal education plays an important role in transmitting messages about nationality to children. The older (9- and 10-year-old) and younger (5- and 6-year-old) children tested in these experiments differ in many respects; one critical difference between these age groups is the amount of formal education they have received. Young children's prioritization of language may recruit intuitive reasoning about social groups, in which language may be especially powerful in guiding young children's social preferences (see Kinzler et al., 2009). In contrast, the nuanced pattern of results demonstrated by older children may reflect a more detailed knowledge of history, civics, and geography that has informed their reasoning about nationality. Alternatively, domain-specific knowledge about nationality may not be required to explain the differences we observed in children's reasoning across age groups. Children are highly observant of the social structures of their communities. As evidence, children as young as age 4 in both the United States and South Africa associate higher levels of wealth with racial groups that are perceived to be high in social status (Olson, Shutts, Kinzler, & Weisman, 2012; Shutts, Brey, Dornbusch, Slywotzky, & Olson, 2016). Children's beliefs about nationality and the link between nationality and social groups may thus be guided by similar processes of informal observation. These patterns may be especially interesting to test in cities that vary in their ethnic and national diversity. For instance, children in Studies 1 and 2 live in racially diverse cities, yet these cities have relatively small Asian and Korean populations compared to metropolitan areas such as Los Angeles, New York, and Washington-Baltimore, according to the 2014 American Community Survey (United States Census Bureau, 2014). Testing how children's experiences vary depending on the composition of their cities or interactions with people of different nationalities is an important direction for future research.

Is nationality a static construct? The findings of the present research suggest that make reliable predictions about the relation between nationality and social categories early in life, but the responses of older children in this study suggest that thinking about nationality undergoes revision and may continue to do so through adolescence and adulthood (see Phinney, 1989, 1993; Phinney & Tarver, 1988). For instance, contentious political contexts may subtly influence adults' political attitudes and the way people conceive of the meaning of nationality (Carter, Ferguson, & Hassin, 2011; Devos & Ma, 2013) but these beliefs may shift over time and be malleable based on the current political climate, such as divisive presidential campaigns compared to non-election years (Ferguson, Carter, & Hassin, 2014; Ma & Devos, 2014). These findings raise interesting questions about the importance of context and the potential malleability of reasoning about nationality across the lifespan. Testing whether children's beliefs about nationality vary depending on the context (e.g., by conducting the study in a room with an American flag vs. flags from different countries) would be an interesting direction for future studies. These findings would complement the present study in revealing that the patterns observed in adults may have their roots in early-emerging, intuitive thinking.

Finally, in contrast to past research that reveals children's failures to reason appropriately about nationality (e.g., Jahoda, 1964; Piaget & Weil, 1951), the present research demonstrates that children reliably associate social group membership with nationality. Young children may not have a detailed understanding of the legal requirements of nationality, yet they still view nationality as a meaningful social group (see Kinzler & DeJesus, 2013). Understanding how early associations between language, race, and nationality develop and how these associations might contribute to biases and prejudice could be critically informative for public debate on controversial political issues (Gluszek & Dovidio, 2010; Lippi-Green, 1997; Matsuda, 1991). Implicit attitudes are related to a variety of behavioral outcomes, including disparities in hiring, health care, and legal decisions (Chapman, Kaatz, & Carnes, 2013; Rachlinski, Johnson, Wistrich, & Guthrie, 2009; Rudman & Glick, 2001). Similarly, implicit attitudes about the link between nationality and social categories may influence discriminatory policies and nationalist attitudes, including those that demonstrate bias towards individuals who were born in the United States with diverse ethnic heritages (e.g., Yogeeswaran & Dasgupta, 2010). Understanding the development and potential malleability of these attitudes is critical to designing future strategies to combat their negative consequences.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NICHD grant R01 HD070890 to KDK, an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1144082) to JMD, and the Earl Franklin Research Fellowship to HGH. We thank Clare Park and Emily Gerdin for assistance in data collection and the University of Chicago Department of Statistics Consulting Program for statistical advice. We also thank the members of the Development of Social Cognition Lab and four anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

References

- Aboud FE. Children and prejudice The development of ethnic awareness and identity. Oxford: Basil Blackwell; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Adi-Japha E, Berberich-Artzi J, Libnawi A. Cognitive flexibility in drawings of bilingual children. Child Development. 2010;81(5):1356–1366. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron AS, Banaji MR. The development of implicit attitudes. Evidence of race evaluations from ages 6 and 10 and adulthood. Psychological Science. 2006;17:53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett MD. Children's knowledge, beliefs and feelings about nations and national groups. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett MD, Wilson H, Lyons E. The development of national in-group bias: English children's attributions of characteristics to English, American and German people. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2003;21:193–220. doi: 10.1348/026151003765264048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bigler RS, Liben LS. A developmental intergroup theory of social stereotypes and prejudice. In: Robert VK, editor. Advances in Child Development and Behavior. Vol. 34. JAI; 2006. pp. 39–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. American elementary school children's attitudes about immigrants, immigration, and being an American. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2011;32(3):109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2011.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byers-Heinlein K, Garcia B. Bilingualism changes children's beliefs about what is innate. Developmental Science. 2015;18:344–350. doi: 10.1111/desc.12248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington B, Short G. What makes a person British: Children's conceptions of their national culture and identity. Educational Studies. 1995;21:217–238. [Google Scholar]

- Carter TJ, Ferguson MJ, Hassin RR. A single exposure to the American flag shifts support toward Republicanism up to 8 months later. Psychological Science. 2011;22:1011–1018. doi: 10.1177/0956797611414726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Intelligence Agency. Korea, South. The World Factbook. 2016 Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/geos/ks.html.

- Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: How doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28:1504–1510. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E. The evolution of tag-based cooperation in humans: The case for accent. Current Anthropology. 2012;53(5):588–616. doi: 10.1086/667654. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conway MM, Wyckoff ML, Feldbaum E, Ahern D. The news media in children's political socialization. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1981;45:164–178. [Google Scholar]

- Corriveau KH, Kinzler KD, Harris PL. Accuracy trumps accent in children's endorsement of object labels. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49:470–479. doi: 10.1037/a0030604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danziger S, Ward R. Language changes implicit associations between ethnic groups and evaluation in bilinguals. Psychological Science. 2010;21:799–800. doi: 10.1177/0956797610371344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos T, Banaji MR. American = White. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:447–466. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos T, Ma D. How “American” is Barack Obama? The role of national identity in a historic bid for the White House. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2013;43:214–226. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devos T, Ma DS. Is Kate Winslet more American than Lucy Liu? The impact of construal processes on the implicit ascription of a national identity. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;47:191–215. doi: 10.1348/014466607X224521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan SP, Liberman Z, Keysar B, Kinzler KD. The exposure advantage: Early exposure to a multilingual environment promotes effective communication. Psychological Science. 2015;26:1090–1097. doi: 10.1177/0956797615574699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson M, Carter T, Hassin R. Commentary on the attempt to replicate the effect of the American Flag on increased Republican attitudes. Social Psychology. 2014;45:301–302. [Google Scholar]

- Foreign population in Seoul continue to dwindle. The Korea Times. 2010 May 25; Retrieved from https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2010/07/113_66455.html.

- Gaither SE, Chen EE, Corriveau KH, Harris PL, Ambady N, Sommers SR. Monoracial and Biracial Children: Effects of racial identity saliency on social learning and social preferences. Child Development. 2014;85:2299–2316. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman SA. The essential child: Origins of essentialism in everyday thought. Oxford University Press; USA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman SA, DeJesus JM. The language paradox: Words invite and impede conceptual change. In: Amin T, Levrini O, editors. Converging and complementary perspectives on conceptual change. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Gluszek A, Dovidio JF. The way they speak: A social psychological perspective on the stigma of nonnative accents in communication. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2010;14:214–237. doi: 10.1177/1088868309359288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld LA. Race in the making: Cognition, culture, and the child's construction of human kinds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda G. Development of Scottish children's ideas and attitudes about other countries. Journal of Social Psychology. 1962;58:91–108. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1962.9712357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda G. Children's concepts of nationality - A critical-study of Piaget's stages. Child Development. 1964;35:1081–1092. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1964.tb05249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay J. Concerning dangers from foreign force and influence. Independent Journal 1787 [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KD, Dautel JB. Children's essentialist reasoning about language and race. Developmental Science. 2012;15:131–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KD, DeJesus JM. Children's sociolinguistic evaluations of nice foreigners and mean Americans. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49:655–664. doi: 10.1037/a0028740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KD, Shutts K, Correll J. Priorities in social categories. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2010;40:581–592. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KD, Shutts K, DeJesus J, Spelke ES. Accent trumps race in guiding children's social preferences. Social Cognition. 2009;27:623–634. doi: 10.1521/soco.2009.27.4.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn H. The idea of nationalism: A study in its origins and background. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács ÁM, Mehler J. Cognitive gains in 7-month-old bilingual infants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009a;106:6556–6560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811323106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács ÁM, Mehler J. Flexible learning of multiple speech structures in bilingual infants. Science. 2009b;325:611–612. doi: 10.1126/science.1173947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzban R, Tooby J, Cosmides L. Can race be erased? Coalitional computation and social categorization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98:15387–15392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251541498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kymlicka W. Theorizing Nationalism. Albany, NY: SUNY Press; 1999. Misunderstanding nationalism; pp. 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman D, Oum R, Kurzban R. The family of fundamental social categories includes kinship: evidence from the memory confusion paradigm. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;38:998–1012. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.528. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lippi-Green R. English with an accent: Language, ideology, and discrimination in the United States. New York: Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Devos T. Every heart beats true, for the red, white, and blue: National identity predicts voter support. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy. 2014;14:22–45. doi: 10.1111/asap.12025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda MJ. Voices of America: Accent, antidiscrimination law, and a jurisprudence for the Last Reconstruction. Yale Law Journal. 1991;100:1329–1407. doi: 10.2307/796694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunnaike O, Dunham Y, Banaji M. The language of implicit preferences. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2010;46:999–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olson KR, Shutts K, Kinzler KD, Weisman KG. Children associate racial groups with wealth: evidence from South Africa. Child Development. 2012;83:1884–1899. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01819.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Stages of ethnic identity development in minority group adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1989;9:34–49. doi: 10.1177/0272431689091004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. A three-stage model of ethnic identity development in adolescence. In: Bernal ME, Knight GP, editors. Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities. Albany, NY: SUNY Press; 1993. pp. 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Tarver S. Ethnic identity search and commitment in Black and White eighth graders. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1988;8:265–277. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J, Weil AM. The development in children of the idea of the homeland and of relations with other countries. International Social Science Bulletin. 1951;3:561–578. [Google Scholar]

- Pietraszewski D, Schwartz A. Evidence that accent is a dedicated dimension of social categorization, not a byproduct of coalitional categorization. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2014;35:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2013.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM. Children's developmental understanding of ethnicity and race. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 1998;7:27–45. doi: 10.1016/S0962-1849(98)80020-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlinski JJ, Johnson SL, Wistrich AJ, Guthrie C. Does unconscious racial bias affect trial judges? Notre Dame Law Review. 2009;84:09–11. [Google Scholar]

- Reizábal L, Valencia J, Barrett M. National identifications and attitudes to national ingroups and outgroups amongst children living in the Basque country. Infant and Child Development. 2004;13:1–20. doi: 10.1002/icd.328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes M, Gelman SA. A developmental examination of the conceptual structure of animal, artifact, and human social categories across two cultural contexts. Cognitive Psychology. 2009;59:244–274. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes M, Gelman SA, Karuza JC. Preschool ontology: The role of beliefs about category boundaries in early categorization. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2014;15:78–93. doi: 10.1080/15248372.2012.713875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SO, Gelman SA. Can White children grow up to be Black? Children's reasoning about the stability of emotion and race. Developmental Psychology. 2016;52:887–893. doi: 10.1037/dev0000132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudman LA, Glick P. Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:743–762. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rydell R, Hamilton D, Devos T. Now they are American, now they are not: Valence as a determinant of the inclusion of African Americans in the American identity. Social Cognition. 2010;28:161–179. doi: 10.1521/soco.2010.28.2.161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin-Wo K. Foreign teachers unenthusiastic over culture course. The Korea Times. 2009 Nov; Retrieved from http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2009/11/117_56212.html.

- Shutts K, Brey EL, Dornbusch LA, Slywotzky N, Olson KR. Children use wealth cues to evaluate others. PloS One. 2016;11:e0149360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavtcheva-Petkova V. “I'm from Europe, but I'm Not European”: Television and children's identities in England and Bulgaria. Journal of Children and Media. 2013;7:349–365. doi: 10.1080/17482798.2012.740416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Souza AL, Byers-Heinlein K, Poulin-Dubois D. Bilingual and monolingual children prefer native-accented speakers. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4:953. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soysal YN. Toward a postnational model of membership. In: Shafir G, editor. The Citizenship Debates. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 1998. pp. 189–217. [Google Scholar]

- Toivonen K, Cullingford C. The media and information: Children's responses to the Gulf War. Journal of Educational Media. 1997;23:51–64. doi: 10.1080/1358165970230104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. Census 2000 Demographic Profile: Chicago. 2000 Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml.

- United States Census Bureau. Census 2010 Demographic Profile: Chicago. 2010a Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml.

- United States Census Bureau. Census 2010 Demographic Profile: Columbus. 2010b Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml.

- United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/data-profiles/2014/

- Van Bavel JJ, Cunningham WA. Self-Categorization with a novel mixed-race group moderates automatic social and racial biases. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35:321–335. doi: 10.1177/0146167208327743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deth JW, Abendschön S, Vollmar M. Children and politics: An empirical reassessment of early political socialization. Political Psychology. 2011;32:147–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00798.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- VanderBorght M, Jaswal VK. Who knows best? Preschoolers sometimes prefer child informants over adult informants. Infant and Child Development. 2009;18:61–71. doi: 10.1002/icd.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherhead D, White KS, Friedman O. Where are you from? Preschoolers infer background from accent. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2016;143:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman K, Johnson MV, Shutts K. Young children's automatic encoding of social categories. Developmental Science. 2015;18:1036–1043. doi: 10.1111/desc.12269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yogeeswaran K, Dasgupta N. Will the “Real” American please stand up? The effect of implicit national prototypes on discriminatory behavior and iudgments. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:1332–1345. doi: 10.1177/0146167210380928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]