Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to investigate both the effects of low gestational age and infant’s neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years of age on the risk of parental separation within 7 years of giving birth.

Design

Prospective.

Setting

24 maternity clinics in the Pays-de-la-Loire region.

Participants

This study included 5732 infants delivered at <35 weeks of gestation born between 2005 and 2013 who were enrolled in the population-based Loire Infant Follow-up Team cohort and who had a neurodevelopmental evaluation at 2 years. This neurodevelopmental evaluation was based on a physical examination, a psychomotor evaluation and a parent-completed questionnaire.

Outcome measure

Risk of parental separation (parents living together or parents living separately).

Results

Ten percent (572/5732) of the parents reported having undergone separation during the follow-up period. A mediation analysis showed that low gestational age had no direct effect on the risk of parental separation. Moreover, a non-optimal neurodevelopment at 2 years was associated with an increased risk of parental separation corresponding to a HR=1.49(1.23 to 1.80). Finally, the increased risk of parental separation was aggravated by low socioeconomic conditions.

Conclusions

The effect of low gestational age on the risk of parental separation was mediated by the infant’s neurodevelopment.

Keywords: parental separation, low gestational age, neurodevelopment outcome, cohort

Strengths and limitations of the study.

This study was based on a large prospective population-based cohort of preterm infants (n=5732).

Appropriate multivariable statistical analyses were used to properly model the complex relationships between low gestational age, neurodevelopmental outcome and the risk of parental separation (mediation analyses and survival Cox models).

The socioeconomic factors known to influence the risk for parental separation were taken into account in order to limit possible confounding bias.

No information was available regarding the relationship between the parents before the birth of their infants.

Given that the gestational age of our reference population was between 32 and 34 weeks, we cannot exclude the existence of a small effect of preterm birth on the risk of parental separation.

Introduction

Understanding the impact of preterm birth on parental separation is critical as parental separation have negative consequences in childhood,1–3 notably on cognitive and psychological developments that can persist in the adolescence4 and adulthood.5 6 In France, 9.9% of marriages entered into in the year 2000 ended in divorce within 5 years (national statistics from the French Institute for Statistics and Economic Studiesi (INSEE)). The increasing number of preterm births makes these questions more and more topical. Moreover, these questions are of great concern in public health and for structures such as preterm infants’ parental organisations.

The birth of a preterm7–12 or very low birth weight infant (VLBW)10 13–15 is a stressful event for the parents. Compared with mothers of full-term infants, mothers of preterm infants have been shown to have a higher risk of experiencing psychological distress and depressive symptoms following the infant’s birth.16–18 In addition to psychological distress, the birth of a preterm infant frequently has a substantial economic impact on the family involved.19 20 All these factors that affect the life of the family can have negative consequences for the relationship between the parents.

A neurodevelopmental disability following a preterm birth could mediate, at least partly, the effect of preterm birth on parental separation. On the one hand, preterm births are indeed associated with a high risk of neurodevelopmental disabilities.21 22 On the other hand, neurodevelopmental disabilities have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of parental separation.23–30 However, no longitudinal study has investigated the complex relationships between low gestational age (GA), neurodevelopmental outcome and parental separation. The objective of this study was to investigate, in a large longitudinal population-based cohort of preterm infants, both the effects of low GA and the infant’s neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years of age on the risk of parental separation within 7 years of giving birth.

Materials and methods

Study population

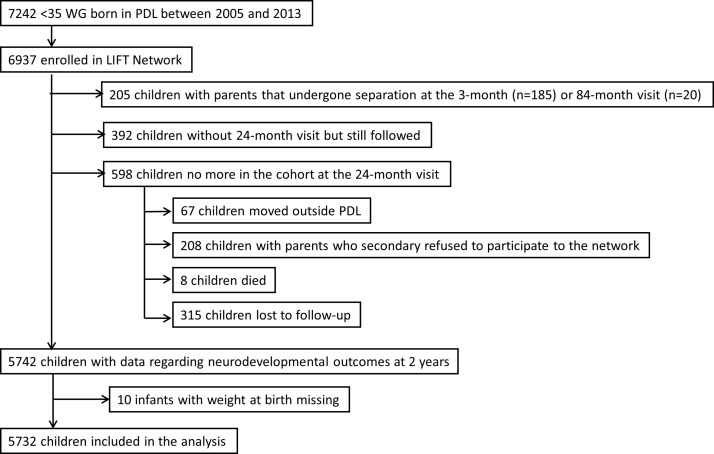

The study population was composed of surviving preterm infants enrolled in the Loire Infant Follow-up Team (LIFT),31 born at <35 weeks of gestation between January 2005 and December 2013, and who were evaluated at 2 years of corrected age to assess their neurodevelopmental outcomes (figure 1). The LIFT network includes 24 maternity clinics in the Pays-de-la-Loire region (one of the 13 administrative regions in France) with the objective to screen for early clinical anomalies associated with preterm births and to provide specifically adapted care. The follow-up consisted of standardised visits by trained physicians at 3, 6, 9, 18 and 24 months as well as at 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 years after the birth of the infant. Data used in this study were routinely collected (ie, not collected for the purpose of the study).

Figure 1.

Flowchart. LIFT, Loire Infant Follow-up Team; PDL, Pays-de-la-Loire region; WG, weeks of gestation.

Perinatal data

Perinatal data comprised the date of birth, gender, GA and birth weight. The birth weight Z-score was computed according to the Olsen standards.32

Parental situation

Information regarding relationship status was binary (ie, as parents living together or parents living separately). For parents who had separated, the first date at which they were reported to be separated was used. Relationship status was not available at the time of inclusion. Consequently, for the separations reported at the 3-month visit, there was the possibility that the parents had already undergone separation at the time of the infant’s birth. Therefore, to ensure temporality between preterm birth and parental separation, separations reported at the 3-month visit were excluded.

Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years

Infants were evaluated at 2 years of corrected age. Assessment to define optimal and non-optimal neurodevelopmental outcomes included a physical examination by a LIFT-trained paediatrician, a psychomotor evaluation by a LIFT network psychologist and a parent-completed questionnaire. Neuromotor evaluation was regarded as non-optimal in the case of cerebral palsy or when the physical examination revealed relatively milder signs of abnormal movement during independent walking according to the Amiel-Tison criteria.33 Psychomotor evaluation was assessed with the revised Brunet-Lézine test (four domains: movement/posture, coordination, language and socialisation).34 The mean and maximal global scores were 100 and 140, respectively, and values of <85 were considered non-optimal psychomotor development. Infants who were not able to perform the revised Brunet-Lézine test were considered to have non-optimal psychomotor development. Furthermore, neurodevelopmental outcome was assessed with the parent-completed ‘Ages and Stages Questionnaire’ (ASQ).35 36 The ASQ assesses development in the following five areas: communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem solving and sociopersonal skills. The maximal overall ASQ score is 300 and a score of <185 was considered non-optimal.37 Finally, sensory disabilities such as blindness or infants that required a hearing aid were taken into account. Overall, infants with a non-optimal neuromotor and/or psychomotor assessment and/or a sensory disability were regarded as having a ‘non-optimal neurodevelopmental outcome’. Infants without a documented physical examination or psychomotor assessment were considered as non-assessable at 2 years except for infants with severe neurological disabilities. This definition of non-optimality has been used in other studies.38–40 To simplify matters, a non-optimal neurodevelopmental outcome will be referred to as non-optimality.

Socioeconomic information

The socioeconomic data consisted of the socioeconomic level and eligibility for social security benefits for those with low incomes. The socioeconomic level took into account the parent with the more highly rated job according to a scale based on the official classification developed by the INSEE institute. The socioeconomic level and eligibility for social security benefits for those with low incomes were considered as two-level categorical variables.

Urbanicity of the residential municipality

The residential municipality was considered either urban or rural based on definitions developed by the INSEE institute. Municipalities were considered rural or urban depending on the distance between buildings and the number of inhabitants.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were conducted in three steps. First, the crude associations between GA and non-optimality at 2 years and the risk of parental separation were investigated with Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests.

Second, a mediation analysis was used to estimate the proportion of the effect of low GA on the risk of parental separation that was mediated by non-optimality at 2 years. The aim of a mediation analysis is to decompose the effect of an exposure on an outcome into a direct effect and an indirect effect that is mediated by an intermediate variable (the mediator). Mediation analyses used were based on the counterfactual framework. A counterfactual variable describes what would have happened if we had intervened on exposure. This framework allows the decomposition of the causal effect into a so-called natural direct and natural indirect effect. A natural direct effect measures the change in outcome (the risk of parental separation) that would be observed if we could change the exposure (low GA) but leave the mediator (optimality at 2 years) at the value it naturally takes when the exposure is left unchanged. A natural indirect effect measures the change in outcome (the risk of parental separation) that would be observed if we could change the mediator (optimality at 2 years) as much as it would naturally change when exposure was changed without actually changing the exposure (low GA). GA was considered as a three-level categorical variable: GA 32–34 (reference), GA 28–31 (very preterm birth) and GA 24–27 weeks (extremely preterm birth). The estimations of natural direct and indirect effects were done while adjusting for the possible confounding factors: gender, multiple pregnancies (‘yes’ or ‘no’), Z-score of birth weight (<−1, between −1 and 0, between 0 and 1, and ≥1), socioeconomic level (‘high’ or ‘intermediate’), social security benefits for those with low incomes (‘yes’ or ‘no’) and urbanicity of the residential municipality (‘urban’ vs ‘rural’). Moreover, this analysis accounted for the censored nature of the outcome. The possible interaction between the exposure and the mediator was tested. Mediation models used here are based on natural effect models41 implemented in the R package medflex.

Third, the effect of the non-optimality at 2 years on the risk of parental separation was estimated using the multivariable Cox model. Furthermore, the effect of gestation age on non-optimality at 2 years was estimated using logistic regression. For these two models, the same adjustment variables as those considered in the mediation analysis were included in the models. All analyses were performed using R softwareii.

Four sensitivity analyses were performed. In the first one, parental separations occurring before the 24-month visit were excluded to ensure the temporality between neurodevelopmental outcome and parental separations. In the second analysis, an imputation of the missing data was performed using a multiple imputation method. The third analysis concerned the comparison of the characteristics of the infants who were lost to follow-up between 2 and 5 years and those who were still followed at 5 years. Finally, a last analysis was performed by keeping only one infant from each twins’ pair to check the robustness of the results regarding the assumption of non-independence between twins.

Results

Between January 2005 and December 2013, 6937 infants born at <35 weeks of gestation in the Pays-de-la-Loire region, France, were enrolled in the LIFT cohort. The following infants were excluded from the study population: infants whose parents were separated at the 3-month (n=185) or 84-month visit (n=20), infants without neurodevelopmental evaluation at 2 years but still followed (n=392) and infants lost to follow-up at 2 years (n=315). In light of these exclusions, the study population consisted of 5732 preterm infants, corresponding to 83% of the infants initially enrolled in the cohort (figure 1).

During the follow-up, 10.0% of the parents reported having undergone separation (n=572), corresponding with an incidence rate of 23.8 separations per 1000 infant-year. The median time at which separations were reported was 22 months following the birth of the infant with an IQR of 10.3–43.3 months. 30.2% (n=1730) and 8.9% (n=508) of the infants were born very or extremely preterm, respectively. 19.1% (n=1096) of the infants were considered non-optimal at 2 years. Lastly, the median length of the total follow-up was 56 months (IQR=32.1–69.2) (table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the study population and comparison between preterm infants included in the study and those not included

| Variable | Category | Included (n=5732) | Not included (n=1205) | p Value |

| Number (%) | Number (%) | |||

| GA (weeks) | 32–34 | 3494 (61.0) | 802 (66.6) | <0.001 |

| 28–31 | 1730 (30.2) | 321 (26.6) | ||

| 24–27 | 508 (8.9) | 82 (6.8) | ||

| Gender | Woman | 2640 (46.1) | 589 (48.9) | 0.079 |

| Man | 3092 (53.9) | 616 (51.1) | ||

| Multiple pregnancy | No | 3617 (63.1) | 830 (68.9) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 2115 (36.9) | 375 (31.1) | ||

| Z score of birth weight | <−1 | 1378 (24.0) | 285 (23.9) | 0.999 |

| −1 to 0 | 2044 (35.7) | 426 (35.7) | ||

| 0 to 1 | 1787 (31.2) | 371 (31.1) | ||

| >1 | 523 (9.1) | 110 (9.2) | ||

| Socioeconomic level | Intermediate | 4254 (74.2) | 1024 (85.0) | <0.001 |

| High | 1478 (25.8) | 181 (15.0) | ||

| SSB due to low income | No | 5031 (87.8) | 968 (80.3) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 701 (12.2) | 237 (19.7) | ||

| Urbanicity | Rural | 2104 (36.7) | 376 (31.2) | <0.001 |

| Urban | 3628 (63.3) | 829 (68.8) | ||

| Length of follow-up (months) (median (IQR)) |

56 (32.1–69.2) | 16.6 (8.1–56.9) | <0.001 |

GA, gestation age; SSB, social security benefits.

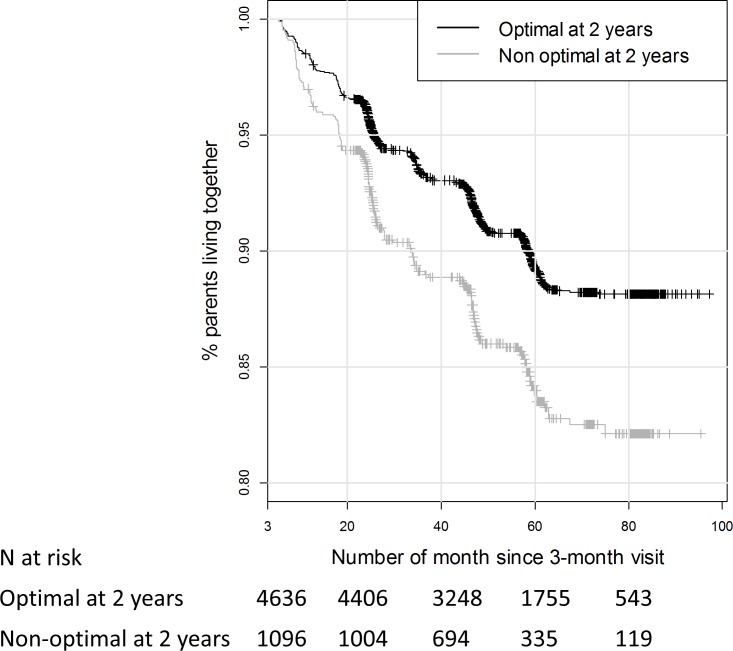

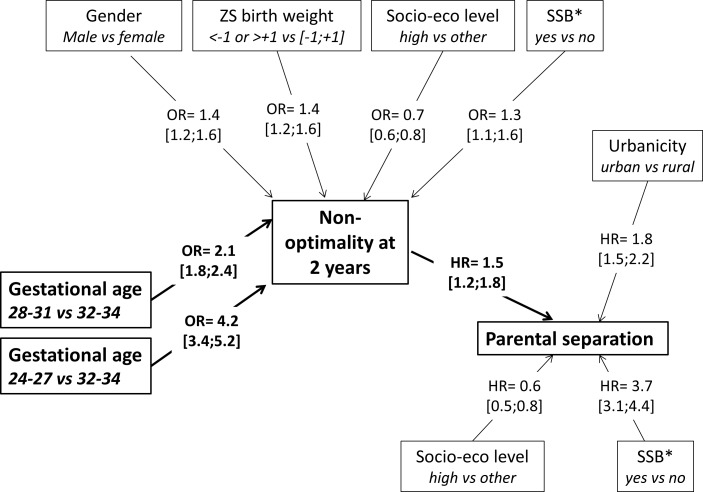

In the bivariable analysis, both GA and non-optimality at 2 years were associated with an increased risk of parental separation (online supplementary table 1, figure 2). However, the mediation analysis showed that all the effect of low GA in very and extremely preterm infants on the risk of parental separation was mediated by the non-optimality at 2 years of age (online supplementary figure 1). Preterm birth were associated with a higher risk of non-optimal neurodevelopment at 2 years, corresponding to OR=2.1 (1.8 to 2.4) and OR=4.2 (3.4 to 5.2) for very and extremely preterm infants, respectively (online supplementary table 2). The non-optimality at 2 years was associated with an increased risk of parental separation corresponding to a HR=1.49 (1.23 to 1.80) (table 2, figure 3). Furthermore, a significant interaction was found between non-optimality and social security benefits due to low income on the risk of parental separation (online supplementary table 3). Finally, a lower parental socioeconomic level, receiving social security benefits due to low income and living in urban areas were associated with a higher risk of parental separation. The area under the curve of this model was 0.69. The results of the relationships between GA, non-optimality and parental separation are summarised in figure 3.

Figure 2.

Relationship between the neurodevelopment of preterm infants and the occurrence of parental separation, using Kaplan-Meier curves (n=5732).

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted association between the neurodevelopment of preterm infants and the risk of parental separation. Adjustment was made on perinatal characteristics of the infants, the socioeconomic level of the family and the urbanicity of the residential municipality (n=5732)

| Category | n (%) | Raw HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |

| Optimality at 2 years* | Yes | 4636 (80.9) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 1096 (19.1) | 1.58 (1.31 to 1.90) | 1.49 (1.23 to 1.80) | |

| Gender | Woman | 2640 (46.1) | 1 | 1 |

| Man | 3092 (53.9) | 1.07 (0.90 to 1.26) | 1.07 (0.91 to 1.27) | |

| Multiple pregnancy | No | 3617 (63.1) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 2115 (36.9) | 0.94 (0.79 to 1.11) | 0.97 (0.81 to 1.15) | |

| Z score of birth weight | <−1 | 1378 (24.0) | 1 | 1 |

| −1 to 0 | 2044 (35.7) | 1.03 (0.84 to 1.28) | 1.1 (0.89 to 1.36) | |

| 0 to 1 | 1787 (31.2) | 0.9 (0.72 to 1.12) | 0.96 (0.77 to 1.20) | |

| >1 | 523 (9.1) | 0.96 (0.70 to 1.33) | 1.03 (0.75 to 1.43) | |

| Socioeconomic level | Intermediate | 4254 (74.2) | 1 | 1 |

| High | 1478 (25.8) | 0.62 (0.50 to 0.76) | 0.64 (0.52 to 0.79) | |

| SSB due to low income | No | 5031 (87.8) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 701 (12.2) | 4.09 (3.43 to 4.86) | 3.68 (3.09 to 4.39) | |

| Urbanicity | Rural | 2104 (36.7) | 1 | 1 |

| Urban | 3628 (63.3) | 1.91 (1.57 to 2.31) | 1.81 (1.49 to 2.20) |

*Infants with a non-optimal neuromotor and/or psychomotor assessment and/or sensorial disability at 2 years were considered as non-optimal.

SSB, social security benefits.

Figure 3.

Summary of the relationships between low GA, neurodevelopment of preterm infants (non-optimality at 2 years) and the risk of parental separation. OR and HR were estimated using two different models (because of the absence of direct effect of low GA on the risk of parental separation). Model 1: logistic regression with outcome=non-optimality at 2 years and exposure=gestational age. Model 2: Cox model with outcome=parental separation and exposure=non-optimality at 2 years. Adjustment variables for both models: gender, multiple pregnancies, Z-score of birth weight, socioeconomic level, social security benefits for those with low incomes and urbanicity of the residential municipality. Only significant adjustment variables were reported in this figure. GA, gestational age; *SSB: social security benefits due to low income; ZS, Z-score

bmjopen-2017-017845supp001.pdf (541.2KB, pdf)

Discussion

Using a large population-based cohort study, we found that the effect of low GA on the risk of parental separation was entirely mediated by the neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years. Parents of preterm infants with a non-optimal neurodevelopment at 2 years were 50% more likely to have undergone separation in the years following the birth of the infant, independently of the socioeconomic factors. This increased risk was further aggravated by low socioeconomic conditions.

A strength of this study was the use of mediation analysis. Because of the association between GA and neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years, mediation analysis is a relevant approach to investigate the effects of GA and neurodevelopmental outcome on the risk of parental separation. An alternative approach would have been to build a single model predicting parental separation with these two risk factors and the adjustment variables. However, this model would not have accounted for the strong association between GA and neurodevelopmental outcome and, therefore, could have led to biased results. A further strength of this study was the large number of infants included, which allowed a high statistical power to be attained. In addition, the longitudinal data and the corresponding survival analyses allowed us to account for the timing of parental separations, rather than simply distinguishing between whether the parents were living together or not. Furthermore, the socioeconomic factors known to influence the risk for parental separation were taken into account. For infants whose parents underwent separation before the 24-month visit (n=221), there was a doubt regarding the temporality between the neurodevelopmental outcome and the parental separation. The sensitivity analysis showed that without these infants, the results were exactly the same, probably due to the early occurrence of neurodevelopment impairments during the infant’s development (online supplementary table 4). Moreover, a sensitivity analysis was performed after imputation of the missing data (n=1000) using a multiple imputation method. The robustness of the results demonstrated the absence of bias related to missing data (online supplementary table 5). Finally, the analysis performed by keeping only one infant from each twins’ pair showed similar results (online supplementary table 6).

The present study has several limitations. First, this study may underestimate the proportion of parental separation due to a bias in the declaration of relevant information; for example, during the examination of the infant by the paediatrician there could a degree of reluctance from the parents to reveal that they are no longer living together. In our study, 12.3% of the parents were found to have undergone separation within an average follow-up time span of 5 years (including separations occurring at the 3-month and 84-month visits that were excluded from analyses). National statistics from the INSEE institute state that 9.9% of marriages entered into in the year 2000 ended in divorce within 5 years, suggesting the absence of bias in parental separation declaration. Second, the characteristics of infants that were excluded from the study population were not comparable to those who were included (table 1). For example, late preterm infants born to families with a lower socioeconomic level were over-represented in the category that was not included for the analysis. However, the absolute differences in the perinatal characteristics were rather small, thus indicating that inclusion criteria did not result in an obvious selection bias. Third, given that the GA of our reference population was between 32 and 34 weeks, we cannot exclude the existence of a small effect of preterm birth on the risk of parental separation, although one that is not detectable with our study design. Further studies using a population of full-term infants as reference are needed to confirm our results. Fourth, no information was available regarding the relationship between the parents before the birth of their infants. A very conflictual relationship might be associated with a higher risk of giving birth to a preterm infant. Our study could, therefore, overestimate the effect of a non-optimal neurodevelopment on the risk of parental separation. Fifth, some factors that may be associated with parental separation were not available in this study and were thus not accounted for, such as the age of the parents or the number of children living in the household. Finally, some infants were lost between 2 and 5 years of follow-up (1518 out of 4813). These infants had slightly different characteristics (online supplementary table 7). However, no difference was observed for the proportion of parents who underwent separation.

In the present study, optimality was defined using neuromotor, psychomotor and sensory evaluations, thereby revealing particularly severe pathologies or clinical symptoms. The association between optimality and parental separation is in accordance with the results of previous studies demonstrating negative consequences on the parent’s relationship in case of a severe disease.24–26 Interestingly, parents of extremely preterm infants with an optimal neurodevelopment at 2 years did not have a higher risk of separation. The increased risk of separation by parents of VLBW (<1500 g)42 in a US national survey conducted on 6016 births might be due to the fact that occurrences of disability were not taken into account during the follow-up. Therefore, we agree with the authors’ statement that their values may be regarded as conservative estimates of the effect of infant disability on parental separation. While a preterm birth may not, on average, be directly responsible for the disruption of a couple’s relationship, the discovery of associated severe infant disabilities or neurodevelopmental delays could profoundly challenge the parent’s relationship. The increased risk of parental separation seems to be due to the presence of repeated stressful events within the first years of the infant’s life. Lastly, this study provides evidence for a major impact of socioeconomic factors on the risk of parental separation. This result is in accordance with several studies that showed no or limited parental education and low family income are strong risk factors for separation,26 29 43 44 parental stress13–15 and psychological distress.16

Conclusions

The effect of low GA on the risk of parental separation was mediated by the infant’s neurodevelopment, with 50% more separations among parents of infants with non-optimal neurodevelopment. This increased risk was aggravated by low socioeconomic conditions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

http://www.insee.fr/en/methodes/default.asp?page=definitions/unite-urbaine.htm. Date accessed: February 2016.

R Core Team (2016). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/

Contributors: MH: had the original idea, provided guidance for the statistical analysis and reviewed and revised the manuscript. SN: performed the statistical analysis, the literature searches and wrote the paper. J-BM, GG, HB, CF, BO, VR, CB and J-CR: participated in the data collection, reviewed and revised the manuscript. MP: participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data, reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors: approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the Regional Health Agency of Pays de la Loire.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Commission Nationale de l’Information et des Libertés (No. 851117).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available from the scientific Committee of the LIFT cohort for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential health data. Interested researchers have to comply with the French legislation, that is, require the advice of the “Comité Consultatif sur le Traitement de l’Information en matière de Recherché sur le domaine de la Santé” (CCTIRS) as well as the authorisation of the “Commission Nationale de l’Information et des Libertés” (CNIL) for the treatment of personal health data. Contact information is available at: http://www.reseau-naissance.fr/module-pagesetter-viewpub-tid-2-pid-21.html.

References

- 1. Amato PR, Keith B. Parental divorce and the well-being of children: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 1991;110:26–46. 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allison PD, Furstenberg FF. How marital dissolution affects children: Variations by age and sex. Dev Psychol 1989;25:540–9. 10.1037/0012-1649.25.4.540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lansford JE, Malone PS, Castellino DR, et al. . Trajectories of internalizing, externalizing, and grades for children who have and have not experienced their parents’ divorce or separation. J Fam Psychol 2006;20:292–301. 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Richards M, Wadsworth ME. Long term effects of early adversity on cognitive function. Arch Dis Child 2004;89:922–7. 10.1136/adc.2003.032490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Amato PR, Keith B. Parental divorce and adult well-being: a meta-analysis. J Marriage Fam 1991;53:43–58. 10.2307/353132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hope S, Power C, Rodgers B. The relationship between parental separation in childhood and problem drinking in adulthood. Addiction 1998;93:505–14. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9345056.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meyer EC, Garcia Coll CT, Seifer R, et al. . Psychological distress in mothers of preterm infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1995;16:412–7. 10.1097/00004703-199512000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Younger JB, Kendell MJ, Pickler RH. Mastery of stress in mothers of preterm infants. J Soc Pediatr Nurs 1997;2:29–35. 10.1111/j.1744-6155.1997.tb00197.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Trombini E, Surcinelli P, Piccioni A, et al. . Environmental factors associated with stress in mothers of preterm newborns. Acta Paediatr 2008;97:894–8. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00849.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Singer LT, Salvator A, Guo S, et al. . Maternal psychological distress and parenting stress after the birth of a very low-birth-weight infant. JAMA 1999;281:799–805. 10.1001/jama.281.9.799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schappin R, Wijnroks L, Uniken Venema MM, et al. . Rethinking stress in parents of preterm infants: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e54992 10.1371/journal.pone.0054992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zerach G, Elsayag A, Shefer S, et al. . Long-term maternal stress and post-traumatic stress symptoms related to developmental outcome of extremely premature infants. Stress Health 2015;31:204–13. 10.1002/smi.2547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Singer LT, Fulton S, Kirchner HL, et al. . Parenting very low birth weight children at school age: maternal stress and coping. J Pediatr 2007;151:463–9. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tommiska V, Ostberg M, Fellman V. Parental stress in families of 2 year old extremely low birthweight infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2002;86:F161–4. 10.1136/fn.86.3.F161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wormald F, Tapia JL, Torres G, et al. . Stress in parents of very low birth weight preterm infants hospitalized in neonatal intensive care units. A multicenter study. Arch Argent Pediatr 2015;113:303–9. 10.5546/aap.2015.331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davis L, Edwards H, Mohay H, et al. . The impact of very premature birth on the psychological health of mothers. Early Hum Dev 2003;73:61–70. 10.1016/S0378-3782(03)00073-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miles MS, Holditch-Davis D, Schwartz TA, et al. . Depressive symptoms in mothers of prematurely born infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2007;28:36–44. 10.1097/01.DBP.0000257517.52459.7a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pace CC, Spittle AJ, Molesworth CM, et al. . Evolution of depression and anxiety symptoms in parents of very preterm infants during the newborn period. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:863 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McCormick MC, Bernbaum JC, Eisenberg JM, et al. . Costs incurred by parents of very low birth weight infants after the initial neonatal hospitalization. Pediatrics 1991;88:533–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kusters CD, van der Pal SM, van Steenbrugge GJ, et al. . [The impact of a premature birth on the family; consequences are experienced even after 19 years]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2013;157:A5449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bhutta AT, Cleves MA, Casey PH, et al. . Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2002;288:728–37. 10.1001/jama.288.6.728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet 2008;371:261–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60136-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reichman NE, Corman H, Noonan K. Impact of child disability on the family. Matern Child Health J 2008;12:679–83. 10.1007/s10995-007-0307-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Joesch JM, Smith KR. Children’s health and their mothers’ risk of divorce or separation. Soc Biol 1997;44:159–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tew BJ, Laurence KM, Payne H, et al. . Marital stability following the birth of a child with spina bifida. Br J Psychiatry 1977;131:79–82. 10.1192/bjp.131.1.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reichman NE, Corman H, Noonan K. Effects of child health on parents’ relationship status. Demography 2004;41:569–84. 10.1353/dem.2004.0026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hartley SL, Barker ET, Seltzer MM, et al. . The relative risk and timing of divorce in families of children with an autism spectrum disorder. J Fam Psychol 2010;24:449–57. 10.1037/a0019847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lederman VRG, Alves BdosS, Negrão J, et al. . Divorce in families of children with down syndrome or rett syndrome. Cien Saude Colet 2015;20:1363–9. 10.1590/1413-81232015205.13932014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lau S, Lu X, Balsamo L, et al. . Family life events in the first year of acute lymphoblastic leukemia therapy: a children’s oncology group report. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:2277–84. 10.1002/pbc.25195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mauldon J. Children’s risks of experiencing divorce and remarriage: do disabled children destabilize marriages? Popul Stud 1992;46:349–62. 10.1080/0032472031000146276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hanf M, Nusinovici S, Rouger V, et al. . Cohort profile: longitudinal study of preterm infants in the Pays de la Loire region of France (LIFT cohort). Int J Epidemiol 2017. 10.1093/ije/dyx110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Olsen IE, Groveman SA, Lawson ML, et al. . New intrauterine growth curves based on United States data. Pediatrics 2010;125:e214–e224. 10.1542/peds.2009-0913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Amiel-Tison C. Update of the Amiel-Tison neurologic assessment for the term neonate or at 40 weeks corrected age. Pediatr Neurol 2002;27:196–212. 10.1016/S0887-8994(02)00436-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Josse D. Revised Brunet–Lezine scale of psychomotor development of first childhood [in French]. Paris, France: Etablissement D’Applications Psychotech, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Squires J, Bricker D, Potter L. Revision of a parent-completed development screening tool: ages and stages questionnaires. J Pediatr Psychol 1997;22:313–28. 10.1093/jpepsy/22.3.313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Skellern CY, Rogers Y, O’Callaghan MJ. A parent-completed developmental questionnaire: follow up of ex-premature infants. J Paediatr Child Health 2001;37:125–9. 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2001.00604.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Flamant C, Branger B, Nguyen The Tich S, et al. . Parent-completed developmental screening in premature children: a valid tool for follow-up programs. PLoS One 2011;6:e20004 10.1371/journal.pone.0020004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gouin M, Nguyen S, Savagner C, et al. . Severe bronchiolitis in infants born very preterm and neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years. Eur J Pediatr 2013;172:639–44. 10.1007/s00431-013-1940-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Leroux BG, N’guyen The Tich S, Branger B, et al. . Neurological assessment of preterm infants for predicting neuromotor status at 2 years: results from the LIFT cohort. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002431 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gouin M, Flamant C, Gascoin G, et al. . The association of urbanicity with cognitive development at five Yyears of age in preterm children. PLoS One 2015;10:e0131749 10.1371/journal.pone.0131749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lange T, Vansteelandt S, Bekaert M. A simple unified approach for estimating natural direct and indirect effects. Am J Epidemiol 2012;176:190–5. 10.1093/aje/kwr525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Swaminathan S, Alexander GR, Boulet S. Delivering a very low birth weight infant and the subsequent risk of divorce or separation. Matern Child Health J 2006;10:473–9. 10.1007/s10995-006-0146-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jena AB, Goldman DP, Joyce G. Association between the birth of twins and parental divorce. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:892–7. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182102adf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Urbano RC, Hodapp RM. Divorce in families of children with Down syndrome: a population-based study. Am J Ment Retard 2007;112:261.doi:10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[261:DIFOCW]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017845supp001.pdf (541.2KB, pdf)