Abstract

Objectives

To describe the impact on early-onset group B Streptococcus (EOGBS) infection rates following reversion from screening-based to risk-based intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis (IAP) for prevention.

Setting

Maternity services provided by secondary healthcare organisation in North West London.

Participants

All women who gave birth in the healthcare organisation between April 2016 and March 2017. There were no exclusions.

Design

Observational study comparing EOGBS rates in the postscreening period (2016–2017) with prescreening (2009–2013) and screening periods (2014–2015).

Methods

Local guidelines for risk-based IAP were reintroduced in April 2016. Compliance with guidelines was audited. Gestational age, mode of delivery, maternal demographics and EOGBS rates in three time periods were compared using Poisson regression analysis. EOGBS was defined through GBS being cultured from blood, cerebrospinal fluid or other sterile fluids within 6 days of birth.

Primary outcome

EOGBS rates/1000 live births in prescreening, screening and postscreening periods

Results

Incremental changes in maternity population were observed throughout the study period (2009 onwards), in particular the ethnic profile of mothers. Of the 5033 live births in postscreening period, 9 babies developed EOGBS infection. Only one of the mothers of affected babies had a risk factor indicating use of IAP. Comparison of postscreening period with screening period showed a fivefold increase in EOGBS rates after adjustment for ethnicity (1.79 vs 0.33/1000 live births; risk ratio =5.67, p=0.009). There was no significant difference between prescreening and postscreening periods with rates of infection reverting to their prescreening level.

Conclusions

This study provides further evidence of efficacy of screening-based IAP compared with risk-based IAP in prevention of EOGBS in newborns in an area of high incidence.

Keywords: maternal medicine, microbiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first published report of comparison of temporal associations between EOGBS rates and two preventive approaches (risk based or screening) in three time periods (prescreening, screening and postscreening).

As our results are based on an observational rather than experimental study design, our findings might be explained by factors other than the prevention approach.

As a single-centre study, our findings may not be generalisable to other units.

Introduction

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) infection is the the most common cause of neonatal sepsis and meningitis in the UK.1

In the UK, rates of invasive infant GBS disease have risen over the past 20 years.2

The British Paediatric Surveillance Unit (BPSU) recently undertook an enhanced surveillance of invasive GBS infection in babies born 2014–2015 in the UK and Ireland. The survey reported EOGBS rates of 0.57 per 1000 live births compared with a rate of 0.48 per 1000 live births in a similar survey undertaken in 2000–2001.3 The increase in EOGBS rates occurred despite the introduction of national guidelines since 2003 recommending a risk-based prevention approach for offering intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP).4

Current strategies for prevention of EOGBS infections are based on the use of IAP, which is known to reduce EOGBS infection by 85%–90%.5 According to the risk-based IAP (RBIAP) recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), mothers with a history of a baby with invasive GBS infection, GBS colonisation, GBS bacteriuria or infection in the current pregnancy or fever during labour are given intrapartum penicillin (or clindamycin/vancomycin) in women with penicillin allergy.4 6 However, the BPSU survey (2014–2015) observed that 64% mothers of babies who developed EOGBS infection did not have the above risk factors, limiting the potential impact of this approach in further driving down rates of EOGBS. Furthermore, only 44% of the mothers with risk factors were given IAP.3 An alternative strategy for prevention of EOGBS is by a screening-based IAP (SBIAP) approach where pregnant women are screened for GBS in late pregnancy, and carriers are offered intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis. While this approach does necessitate large-scale antibiotic use, significant reductions in EOGBS infections have been reported in countries adopting this approach such as Spain, Canada and the USA.7–9

In a previous paper published in this journal, we reported that despite of RBIAP approach, EOGBS rates in our north-west London hospital had remained consistently higher than the national rates for many years. In 2013, we observed a rate of 1.65/1000 live births, nearly four times the national rate of 0.4/1000 live births reported by Public Health England in 2010. In response to this high rate, we implemented SBIAP in the period March 2014–December 2015. This led to a substantial overall fall in EOGBS rate to 0.33 per 1000 live births and 0.16/live births in babies born to screened women.10

However, as SBIAP did not comply with the current UK guidelines, we were persuaded to revert to RBIAP recommended by the national guidelines. In this paper, we report the change observed in EOGBS infection rates in our organisation following the switch to RBIAP for prevention of EOGBS.

Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to describe the change observed in EOGBS infection rates in our organisation, following the reversion from SBIAP to the nationally recommended RBIAP for prevention of EOGBS.

Methods

Design

This study was a non-randomised observational study compared with historical controls.

Setting

The study was conducted at Northwick Park Hospital, which provides maternity services to the London boroughs of Brent, Harrow and Ealing.

Women who gave birth to live babies at the Northwick Park Hospital in the period April 2016–March 2017 (postscreening period) were included in the study and compared with historical controls. These included women who gave birth in the period 2009–2013 when RBIAP was used (prescreening period) and the period March 2014–December 2015 when SBIAP IAP was implemented (screening period).

Primary outcome

The EOGBS rate (per 1000 live births) in the study period was compared with rates in historical controls with specific reference to the approach used for targeting administration of intrapartum prophylaxis for prevention of EOGBS.

Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis

Local guidelines for IAP were based on the nationally recommended guidelines developed by NICE.6 In brief, women who had a previous baby with GBS infection, GBS bacteriuria or GBS detected in vaginal swab (not by screening) during current pregnancy or intrapartum temperature of >38°C were recommended IAP—benzyl penicillin 3 g intravenously given at onset of labour, and further doses of 1.5 g intravenously given every 4 hours until the birth of the baby. Clindamycin was advised for women who were allergic to penicillin, and cefuroxime was recommended for women with suspected chorioamnionitis.

Identification and assessment of newborns with EOGBS and audits

EOGBS was defined as detection of GBS in the newborn’s blood cultures, cerebrospinal fluid or other sterile fluids. Newborns with EOGBS were identified from microbiology laboratory records. Hospital discharge summaries of affected newborns were reviewed to assess the birth characteristics and outcome of the infection.

A horizontal audit was performed of antenatal and intrapartum records of all mothers of affected babies to identify if risk factors for EOGBS were present and if appropriate IAP was given in labour in accordance with local guidelines.

A vertical audit of randomly selected antepartum and intrapartum records of 60 women (approximately 1.2% of women) was performed to assess overall compliance with the local guidelines.

Statistics

As our intervention was a service improvement initiative rather than a research study, we did not perform a statistical sample size calculation to determine the number of the mothers who needed to be included to demonstrate a statistical difference in invasive EOGBS rates. Rather, all women (total population) during the study period were aimed to be included. We compared the characteristics of the women in the prescreening, screening and postscreening periods. Continuous variables were compared using analysis of variance, while the χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables between groups.

Differences in EOGBS infection rates between prescreening, screening and postscreening time periods were analysed using regression methods. An ‘unadjusted’ analysis was performed and subsequently an analysis adjusted for patient ethnicity. Individual patient data were not available for all time periods, and thus it was not possible to adjust for all patient demographics. The regression analysis was performed using Poisson regression. The difference in EOGBS occurrence between time periods is expressed as a ratio, along with CI for both the unadjusted and adjusted analyses. Significance level was set at p<0.05.

Women with missing demographic data were excluded from analysis.

Results

Gestational ages of the newborn, mode of delivery and demographic characteristics of the women in the prescreening, screening and postscreening periods are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Delivery and maternal characteristics during successive group B streptococcus (GBS) prevention periods targeting women for intrapartum prophylaxis based on risk factors (prescreening and postscreening) or antenatal screening

| Variable | Prescreening 2009 to 2013 (n=25 073) |

Screening 2014 to 2015 (n=9801) |

Postscreening 2016 to 2017 (n=5035) |

p Value |

| Median gestation (weeks)±SD | 39.1±2.1 | 39.1±2.0 | 39.2±1.7 | <0.001 |

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| Caesarean | 7163 (28.6%) | 2909 (29.7%) | 1523 (30.3%) | 0.04 |

| Instrumental | 3162 (12.6%) | 1235 (12.6%) | 605 (12.0%) | |

| Spontaneous vaginal | 14 748 (58.8%) | 5657 (57.7%) | 2907 (57.7%) | |

| Median age (years)±SD | 29.0±5.4 | 29.6±5.3 | 30.2±5.4 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Black | 3401 (13.6%) | 950 (9.7%) | 419 (8.3%) | <0.001 |

| British/Irish | 2665 (10.6%) | 849 (8.7%) | 408 (8.1%) | |

| White other | 4964 (19.8%) | 2596 (26.5%) | 1538 (30.6%) | |

| Indian Subcontinent | 11 811 (47.1%) | 4593 (48.9%) | 2260 (44.9%) | |

| Other | 2232 (8.9%) | 813 (8.3%) | 407 (8.1%) |

Statistically significant incremental changes between the three time periods for all above characteristics were seen, including gestational age, mode of delivery and demographics of the women. Changes to gestational age were slight.

The largest noticeable differences were changes in ethnicity. There was an increase in the percentage in the ‘white other’ group from 20% to reach 31% in the postscreening period and a reduction in black women (14% down to 8%) in the same period. The proportion of white British/Irish women also showed a drop from 11% to 8% between the prescreening and postscreening periods.

During the postscreening period, there were 5033 live births. Nine babies developed EOGBS. The birth characteristics of the babies and maternal risk factors of EOGBS infection in the prescreening (only for 2013), screening (2014, 2015) and postscreening (April 2016-March 2017) are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Maternal and neonatal characteristics in postscreening EOGBS cases

| Characteristics | Prescreening (2013) (n=8) |

Screening (2014, 2015) (n=3) |

Postscreening April 2016-Mar 2017 (n=9) |

| Neonatal | |||

| Sex (M/F) | 3/5 | 2/1 | 7/2 |

| Gestational age range (weeks) | 25–41 | 38–41 | 39–42 |

| Age (days) range at time of detection of infection | 0–6 | 0–6 | 0–6 |

| Group B streptococcus bacteraemia | 8 | 2 | 9 |

| Meningitis | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Fatality | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Maternal | |||

| Preterm Premature rupture of membranes | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Intrapartum fever | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Group B Streptococcus In urine |

0 | 0 | 0 |

| Previous Group B streptococcus infected baby |

0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antepartum Group B Streptococcus in High vaginal swab* | 0 | 0 | 1* |

| Prolonged rupture of membranes (≥12 hrs)† | 1 | 0 | 5 |

One of the term babies died of severe septicaemia secondary to the EOGBS infection.

*Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis not given.

†Not a risk factor in RCOG and NICE guidelines (2012).

EOGBS, early-onset group B Streptococcus; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; RCOG, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

Horizontal audit (table 2) showed that only one of the nine mothers whose babies developed EOGBS had a recognised risk factor. GBS was detected in vaginal swab taken for investigation of discharge during an antenatal visit, but she was not given IAP due to failure to act on the antenatal laboratory result. Another mother developed postpartum fever with GBS bacteraemia 1 day after delivery but did not have any antepartum or intrapartum risk factors. She was treated initially with cefuroxime and metronidazole which was changed to benzyl penicillin following isolation of GBS in blood culture. The mother made an uneventful recovery.

Vertical audit showed that that 3 of the 60 mothers assessed had risk factors. One of the mothers had antenatal GBS bacteriuria, one had GBS in a vaginal swab taken antenatally and another mother had intrapartum fever of >38°C. All three mothers were given IAP according to local and national guidelines.

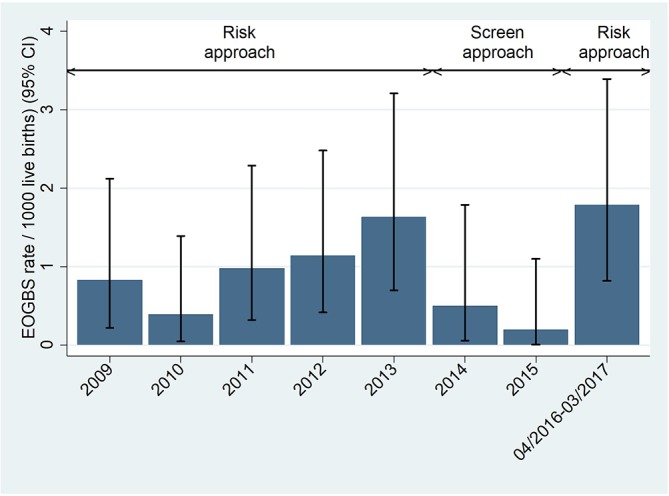

EOGBS rates in the prescreening, screening and postscreening time periods are shown in table 3 and figure 1.

Table 3.

EOGBS rates in the prescreening, screening and postscreening periods

| Time period | EOGBS n/N | EOGBS/1000 cases (95% CI) |

| Prescreening (2009–2013) | 25/25 276 | 0.99 (0.64 to 1.46) |

| Screening (2014–2015) | 3/9098 | 0.33 (0.07 to 0.96) |

| Postscreening (2016–2017) | 9/5033 | 1.79 (0.82 to 3.39) |

EOGBS, early-onset group B Streptococcus.

Figure 1.

Annual rates of early-onset group B streptococcus (EOGBS) infection.

The rates were compared, with and without an adjustment for ethnicity. A summary of the results is given in table 4, which shows comparisons between each pair of time periods.

Table 4.

Risk of EOGBS in prescreening, screening and postscreening periods with and without adjustment for ethnicity

| Reference | Comparator | Unadjusted | Ethnicity adjusted | ||

| Period | Period | Risk ratio (95% CI) |

p Value | Adjusted risk ratio (95% CI) |

p Value |

| Prescreen* | Screening† | 0.33 (0.10 to 1.10) | 0.07 | 0.36 (0.11 to 1.19) | 0.09 |

| Postscreening‡ | 1.81 (0.84 to 3.88) | 0.13 | 1.89 (0.87 to 4.11) | 0.11 | |

| Screening† | Postscreening‡ | 5.42 (1.47 to 20.0) | 0.01 | 5.67 (1.53 to 21.0) | 0.009 |

| Pre+post screening* | Screening† | 0.29 (0.09 to 0.96) | 0.04 | 0.31 (0.09 to 1.00) | 0.05 |

*January–December 2013.

†March 2014-December 2015.

‡April 2016-March 2017.

EOGBS, early-onset group B Streptococcus.

EOGBS rates were around three times lower during the screening period (2014-15) compared to the pre-screening period (2009-2013) and also a combination of pre screening and post screening periods. However, this difference was of borderline statistical significance.

A comparison of rates in the postscreening period (2016–2017) with the screening period (2014–2015) suggested a significant increase in EOGBS rates in the postscreening period. The infection rate increased by over fivefold from the screening to postscreening period (risk ratio (RR): 5.67, CI 1.53 to 21.0, p<0.01). The postscreening EOGBS rate (1.79 per 1000 live births) was not significantly different to the prescreening rate (RR: 1.89, CI 0.87 to 4.11, p>0.05) and similar to the rate in 2013, the year preceding implementation of screening (1.65/1000 live births).

The ethnicity adjusted analyses gave broadly similar results to the unadjusted analyses.

We were not aware of any women developing adverse reactions to IAP through our hospital’s adverse event reporting system (Datix) or through departmental reporting systems in the screening and postscreening periods. We did not collect information regarding adverse reaction to IAP in the prescreening period.

Discussion

In this study, we have described the incidence of EOGBS infection in our maternity services when we reverted to nationally recommended RBIAP approach for administration of IAP to prevent EOGBS infection in newborns after using a SBIAP approach for nearly 2 years. We have used this unique opportunity to compare temporal associations between EOGBS rates and the two approaches in three time periods (prescreening, screening and postscreening). To the best of our knowledge, there are no published reports examining such an association.

This study shows that after adjustment for differences in ethnicity of mothers, there was a fivefold increase in EOGBS rate in the postscreening period compared with the screening period.

We noted in our study small trends in gestational age of the newborns, age of the mothers and caesarean section rates over the three time periods. While these changes could have influenced EOGBS rates, the fact that they changed incrementally across all three study periods precludes any explanation for the drop in EOGBS rates during the screening period being due to these changes. Mothers’ ethnicity, in particular, was found to vary substantially between the time periods although again in a consistent trajectory over the time period. Because differences in EOGBS rates in ethnic groups have been previously observed, we compared the EOGBS rates after adjusting for ethnicity to provide a more robust estimation of the difference in rates of disease within this context of changing maternal ethnic distribution.11 These ethnicity-adjusted analyses gave broadly similar results to the unadjusted analyses. Thus, differences in the EOGBS rates observed in the prescreening, screening and postscreening time periods were likely to be associated with the approach for administering IAP rather than differences in ethnicity.

We believe that this observational study comparing prescreening, screening and postscreening periods provides further evidence that SBIAP approach is significantly more effective in prevention of EOGBS in our setting. These findings are not surprising as SBIAP (which also incorporates the risk factors) has been found to be effective in many countries including the USA, whose baseline incidence of EOGBS was similarly high prior to introducing screening.5

In the UK, RBIAP has been repeatedly recommended by professional bodies such as RCOG and NICE despite a rise in EOGBS rates.4 6

This recommendation is in part due to the possible adverse effects of exposing a large number of women to antibiotics in a screening-based approach compared with RBIAP approach. However, the horizontal audit in our study suggests that the potential for a risk-based approach to be effective in our population is limited as only one of the nine mothers of babies with EOGBS had a recognised risk factor. Unfortunately, she was not given IAP due to failure to act on GBS detected in a vaginal swab taken antenatally. This ‘failure’ highlights some of the challenges in implementing the RBIAP approach.12 13 Our findings are also in keeping with those of BPSU survey. This survey reported that of the 429 EOGBS cases where clinical information was available, only 35% had specified risk factors recommended by the RCOG. Less than half (44%) of these mothers received antibiotics during labour.3 Similar findings have been reported by Eastwood et al in Northern Ireland.14

We share the concerns of professional bodies in the UK regarding the possible adverse effects such as anaphylaxis to penicillin and development of resistance. However, it is reassuring that in the USA, despite administration of penicillin to millions of mothers as IAP since 1996, there have been only four published reports of anaphylaxis associated with GBS chemoprophylaxis, all non-fatal.9 Resistance to penicillin has not been reported in GBS strains isolated from screened women, although strains demonstrating reduced penicillin susceptibility have been detected in other clinical specimens, especially in Japan.9 15 The professional bodies are correct to be cautious about the impact of IAP on the newborn’s microbiota and the theoretical concerns about the long-term consequences for development of the baby.16 Reassuringly, there appears to be no published evidence of developmental issues in the millions of children of mothers who have received penicillin-based IAP.

In conclusion, the findings of this observational study provide further evidence of the efficacy of screening based IAP compared with risk-based IAP in prevention of EOGBS in newborns in an area of high incidence. We believe that in such a setting, the benefit is likely to outweigh any potential risks to the mother or baby.

Limitations

As this is an observational study, our findings could be explained by factors other than the prevention approach. The vertical audit to check for compliance with local guidelines for prevention of EOGBS was performed only on a relatively small random sample of pregnant women and results may not be accurate for total study population. Finally, as a single-centre study, our findings may not be generalisable to other units.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the maternity services, neonatal, audit and research and development departments for supporting this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: GGR, GN and RN were involved in all aspects of the study. JT and DS performed and analysed the audits under the supervision of GGR. SH and PB generated and analysed the data with external advice from TL. All authors contributed to drafting and editing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: Dr G Gopal Rao is a member of the Medical Advisory Board of a UK charity, Group B Streptococcus Support (GBSS)

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Vergnano S, Menson E, Kennea N, et al. . Neonatal infections in England: the NeonIN surveillance network. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2011;96:F9–F14. 10.1136/adc.2009.178798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lamagni TL, Keshishian C, Efstratiou A, et al. . Emerging trends in the epidemiology of invasive group B streptococcal disease in England and Wales, 1991-2010. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:682–8. 10.1093/cid/cit337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Sullivan C, Lamagni T, Efstratiou A, et al. . Group B streptococcal (GBS) disease in UK and irish infants younger than 90 days, 2014-2015. Arch Dis Child 2016;101:A2. [Google Scholar]

- 4. RCOG. The prevention of early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease: green-top guideline no.36. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5. Schrag SJ, Zell ER, Lynfield R, et al. . A population-based comparison of strategies to prevent early-onset group B streptococcal disease in neonates. N Engl J Med 2002;347:233–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa020205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Institute of Care Excellence. Neonatal infection (early onset): antibiotics for prevention and treatment. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg149 (accessed 9 Jul 2017). [PubMed]

- 7. de la Rosa Fraile M, Cabero L, Andreu A, et al. . Prevention of group B streptococcal neonatal disease: a plea for a European consensus. Clin Microbiol Infect 2001;7:25–7. 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2001.00196.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Money D, Allen VM. Infectious diseases committee. The prevention of early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2013;35:939–48. 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30818-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ, et al. . Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease-revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gopal Rao G, Nartey G, McAree T, et al. . Outcome of a screening programme for the prevention of neonatal invasive early-onset group B Streptococcus infection in a UK maternity unit: an observational study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014634 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lamagni TL, Henderson K, Efstratiou A, et al. . Invasive GBS infection in England, 2009: associated risk factors XVIII lancefield international symposium on streptococci and streptococcal diseases, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Royal college of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Audit of current practice inpreventing early-onset neonatalgroup B streptococcal diseasein the UK. 2015. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/research-audit/gbs-audit-first-report.pdf (accessed 21 Jul 2017).

- 13. Royal college of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Audit of current practice in preventing early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease in the UK. 2016. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/research-audit/gbs-audit-second-report-january-2016.pdf (accessed 21 Jul 2017).

- 14. Eastwood KA, Craig S, Sidhu H, et al. . Prevention of early-onset Group B Streptococcal disease - The Northern Ireland experience. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Seki T, Kimura K, Reid ME, et al. . High isolation rate of MDR group B streptococci with reduced penicillin susceptibility in Japan. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70:2725–8. 10.1093/jac/dkv203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mueller NT, Bakacs E, Combellick J, et al. . The infant microbiome development: mom matters. Trends Mol Med 2015;21:109–17. 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.