Abstract

Background

The aims of this study were to gain a better understanding of how bereaved family members perceive the quality of EOL care by comparing their satisfaction with quality of end-of-life care across four different settings and by additionally examining the extent to which demographic characteristics and psychological variables (resilience, optimism, grief) explain variation in satisfaction.

Methods

A cross-sectional mail-out survey was conducted of bereaved family members of patients who had died in extended care units (n = 63), intensive care units (n = 30), medical care units (n = 140) and palliative care units (n = 155). 1254 death records were screened and 712 bereaved family caregivers were identified as eligible, of which 558 (who were initially contacted by mail and then followed up by phone) agreed to receive a questionnaire and 388 returned a completed questionnaire (response rate of 70%). Measures included satisfaction with end-of-life care (CANHELP- Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project - family caregiver bereavement version; scores range from 0 = not at all satisfied to 5 = completely satisfied), grief (Texas Revised Inventory of Grief (TRIG)), optimism (Life Orientation Test – Revised) and resilience (The Resilience Scale). ANCOVA and multivariate linear regression were used to analyze the data.

Results

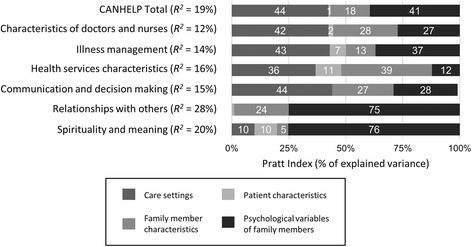

Family members experienced significantly lower satisfaction in MCU (mean = 3.69) relative to other settings (means of 3.90 [MCU], 4.14 [ICU], and 4.00 [PCU]; F (3371) = 8.30, p = .000). Statistically significant differences were also observed for CANHELP subscales of “doctor and nurse care”, “illness management”, “health services” and “communication”. The regression model explained 18.9% of the variance in the CANHELP total scale, and between 11.8% and 27.8% of the variance in the subscales. Explained variance in the CANHELP total score was attributable to the setting of care and psychological characteristics of family members (44%), in particular resilience.

Conclusion

Findings suggest room for improvement across all settings of care, but improving quality in acute care and palliative care should be a priority. Resiliency appears to be an important psychological characteristic in influencing how family members appraise care quality and point to possible sites for targeted intervention.

Keywords: Bereaved family members’, Quality of care, Inpatient healthcare settings, End-of-life care, Palliative care

Background

The quality of care provided to the dying and their family members has become an important health and social policy issue in Canada and in much of the western world. Despite repeated policy directives encouraging a shift in the setting for health care delivery into the home and away from institutions, the majority of Canadians will spend their final days and die in inpatient care settings [1–4]. A review of location of death across 45 countries found that 54% of deaths occur in hospital [5]. Researchers have examined the quality of end-of-life (EOL) care within inpatient care settings such as hospices [6, 7] [8], acute care [9–12], extended care [13–15], critical care [16], and palliative care units [6, 17]. Yet, few studies compare the quality of EOL care across settings from the perspective of family members and, studies that do, tend to focus on comparing inpatient and home care experiences [18] or reporting on barriers to optimal care in general [19]. Little research focuses on how dying in a particular inpatient care setting (i.e., acute care medical units, palliative care units, extended care units and intensive care units) influences family members’ perceptions of the quality of care.

The focus of this research was on the perceptions of bereaved family members because they have experienced the complete episode of care, including the time of death, have important assessments to make related to care quality, and may be more free to express dissatisfaction with care once the patient has died and they are not dependent on the health care system for care. Additionally, how family members perceive the quality of care provided at the EOL can have a profound influence on how they perceive the health care system as a whole [20, 21]. One study in Western Canada, for example, showed that dissatisfaction with acute hospital care was one of the primary reasons why family members opt to provide EOL care at home, even when they are unprepared or reluctant to do so, or when care becomes overly burdensome for them [22]. Negative perceptions about care quality can also influence how family members adjust to the loss of the person close to them [23, 24]. Research has shown that family members’ dissatisfaction with the quality of EOL care is associated with negative psychological outcomes such as prolonged and pathologic grief, depression and decreased quality of life, and, in turn, can contribute to an increase in the utilization of health care resources by bereaved family members [14, 25–28]. Some research has suggested that grief following the loss of a significant other, and both patient and family member demographic characteristics [29, 30], may play a role in influencing how individuals appraise certain events in their life but studies examining these characteristics in relation to how bereaved family members perceive care quality are sparse [31]. In addition, there is some indication that psychological traits such as resilience and optimism, may play a role in how people appraise certain life events. Resilience, defined as the ability to withstand and rebound from crisis and adversity or to transform disaster into a growth experience and move forward, is believed to consist of high levels of self-esteem, personal control, and optimism [32]. While resilience affects appraisal of stress, optimism (the belief that “good things are likely to happen”) diminishes the negative impact of life’s difficult experiences [33]. Resilience and optimism have been suggested as protective against the harmful effects of stress on mental and physical health [34–37], but these concepts have received little attention when studying family perceptions of EOL care.

The overall aim of this study was to gain a better understanding of how bereaved family members perceive the quality of EOL care based on where the patient has died. We define EOL care as care for people in decline who are deemed to be terminal or dying in the foreseeable (near) future [38]. Four care settings were compared: extended care units (ECU), intensive care units (ICU), medical care units (MCU) and palliative care units (PCU). The specific research questions guiding this study were: (1) To what extent are bereaved family members satisfied with the quality of care received at the EOL? (2) Does satisfaction with care vary across different inpatient care settings? and (3) To what extent is satisfaction with care explained by differences in care settings, patient and family member demographics, and psychological variables of family members?

Methods

This study involved analysis of data from a cross sectional survey of bereaved family members using a consecutive sample from death records.

Sample

Structured surveys were completed by a sample of bereaved family members who had a relative or friend die on an ECU, ICU, MCU or PCU in one health region in Western Canada in the past 3–6 months. For the purpose of this study, family member was defined as the person who had the most contact with the dying patient during the last days of life and who could comment on the quality of care provided. Additional eligibility criteria included a length of stay of more than 48 h and the family member being more than 18 years old and able to speak English. Family members were excluded if their relative or friend died because of traumatic causes such as an accident, homicide, suicide, or unexpected myocardial infarction. This exclusion criterion was necessary to ensure that the sample identified was one that would be representative of people who would typically require EOL care.

Settings

In this particular health region three ECUs were represented in the study as they had a sufficient number of resident deaths to allow for evaluation. ECUs, often referred to as nursing homes, provide longer-term residential care for people unable to remain at home and who are diagnosed with chronic conditions including, for example, frailty and dementia. Care is provided primarily by resident care aides and licensed practical nurses under the supervision of a registered nurse. Services from allied health professionals such as social workers, occupation or physical therapists, recreational therapists, chaplaincy and pharmacy also exist. A medical director oversees medical care and is responsible for implementation of relevant policies, but ongoing medical care and monitoring is provided by the patient’s general practitioner. End-of-life care is provided by facility staff with limited or no access to specialist palliative care for complex cases.

The only two ICUs in the health region, both of which are represented in the study, provide care to critically ill patients as a result of trauma or severe exacerbations of illnesses. ICUs typically have a one-to-one registered nurse-to-patient ratio, and access to in-house internists.

The seven MCUs represented in the study provide care for acutely ill patients with a variety of illnesses (malignant and non-malignant conditions), but not requiring surgical interventions. Care in MCUs is provided by licensed practical nurses and registered nurses and the registered nurse-to-patient ratio is considerably lower than for ECU and higher than for ICU (typically one nurse for five to six patients). Services from allied health professionals (most commonly respiratory technicians, social workers, chaplains, occupational and physiotherapists, nutritionists) are also available in ICU and MCU settings depending on patient and family need. Specialist palliative care services are available on referral but access is limited because of resource constraints. In this health region, no regular palliative care consult service is available to acute care, including MCUs and ICUs, or ECUs.

Finally, the only two PCUs in the health region, both of which are represented in the study, offer a total of 27 beds. One of the PCUs has 17 beds and is the primary referral site for complex symptom issues, and has in-house specialist services including palliative care physicians, counsellors, spiritual care providers and a large volunteer base. Adjunct and more limited services are available from occupational and physical therapists, music therapists and pharmacists. Nursing care is provided by licensed practical and registered nurses and supported by a Clinical Nurse Leader. The other PCU has 10 beds, with care provided by licensed practical and registered nurses. A palliative care physician is employed for approximately 10 h per week to oversee medical care and is responsible for implementation of relevant policies. Ongoing medical care and monitoring is provided by general practitioners, depending on the severity of symptoms. There are resources from allied health professionals (i.e., social work, spiritual care/chaplains, music therapy, pharmacy, occupational and physical therapy) to support the unit that are shared with other hospital units at the site. On occasion, patients from this unit are transferred to the 17-bed PCU at the request of family or when the care situation requires more resources than this unit can provide. The nurse-to-patient ratio is typically one nurse to for four to five patients on both of these units, and the large majority of patients being cared for have a malignancy.

Recruitment

To identify eligible bereaved family members, permission was received from the health authority to screen and access death records. Registered nurses employed by the health authority were hired as research assistants to review the charts of patients who had died and identify a contact person. Letters describing the study were then sent by the research assistants (health region employees) to each eligible contact. A follow-up phone call from the research assistant was made to determine if the contact person on the chart was most involved with the patient’s care and if so, they were invited to participate. In the cases where no one answered, up to five phone calls were made on different days of the week and at different times of the day. If the identified contact person said they were unable to comment on the quality of care, they were asked to identify an alternate who was then contacted.

Data collection

Those agreeing to participate were mailed a questionnaire by the research assistant and asked to return it in a pre-addressed stamped envelope. However, six participants (1.5% of the sample) requested to complete the questionnaire by phone and this was accommodated. Family members of patients who received care in multiple care settings in their last month of life (because of in-patient transfers) were asked to rate the care of the setting in which their loved one died. All family members signed a letter of informed consent prior to participating. Ethical approval for the study was granted by a university-based ethics review board.

Instruments

Satisfaction with EOL care in the last month of their relative or friend’s life was measured using the CANHELPa (Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project) instrument [39, 40]. This self-report instrument was developed and validated for patients at the EOL and their family members to assess satisfaction with a variety of actionable items. The CANHELP Bereavement version used in this study was a 43-item instrument with two items about overall satisfaction with care, and 41 items that fall into one of six quality of care subscales that each had good internal consistency reliability (based on the ordinal alpha; [41]) in our study sample: doctor and nurse characteristics (8 items; ordinal alpha = 0.94); illness management (9 items; ordinal alpha = 0.92); health service characteristics (4 items; ordinal alpha = 0.81); communication and decision-making (11 items; ordinal alpha = 0.92); you and your relationships with others (5 items; ordinal alpha = 0.73); and spirituality and meaning (4 items; ordinal alpha = 0.89). Responses to each item are scored on a 5-point scale ranging from ‘not at all satisfied’ (1) to ‘completely satisfied’ (5). A ‘not applicable’ response category is available for items that family members believe do not apply to their particular situation. The subscale scores are the means of the corresponding items and the total score is the mean of the 41 items (ordinal alpha = 0.96), with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction (ranging from 1 to 5).

In addition to demographic information collected as part of the self-report questionnaire, participant grief, optimism and resilience were also measured. Level of grief in bereavement was measured using the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief (TRIG) [42, 43]. This is a Likert-type measure in two parts. Part 1 comprises eight items, measuring initial grief around the time of death; Part 2, with 13 items, assesses present grief. Responses are scored on a 6-point scale ranging from completely true (1) to completely false (6). The authors reported acceptable internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) of 0.77 (Part 1) and 0.86 (Part 2) and a test-rest reliability of 0.74 (Part 1) and 0.88 (Part 2). The overall TRIG score, based on the mean of all item responses, was used in the analysis. Higher scores are indicative of less grief.

Optimism was measured using the Life Orientation Test – Revised, a personality measure used to assess individual differences in generalized optimism [44, 45]. This is a 10-item measure scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (4). The authors provide evidence for internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .78) and Given et al. [34] also reported moderate internal consistency with family caregivers of cancer patients (Cronbach’s alpha = .80). The overall optimism score based on the average of all 10 items (after reverse coding of negatively worded items) was used in this study, with higher scores indicating greater optimism.

Resilience was measured using a resilience scale developed by Wagnild and Young [46]. This measure is comprised of 25 questions using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strong disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). Authors provide evidence for this measure’s internal consistency (Cronbach alpha = .72–.94) and test-retest reliability (r = .67–.84), construct validity, and concurrent validity [47]. This measure has been widely used to identify the degree of individual resilience (personal competence and acceptance of self and life) in multiple groups (adolescents, younger and older adults) [48]. The overall resilience measure, based on the average mean score of all items, was used in this study, with higher scores indicating greater resilience.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations [SD] for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables) were used to descibe the demographic variables. To examine differences in demographics between settings, chi-square tests were used for the categorical variables, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for age, a continuous variable. The first research question was addressed by examining the distributions of the CANHELP total and subscale scores.

Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to evaluate the extent to which the CANHELP total score and the subscale scores differed across the four types of settings (research question #2), while controlling for variability in patient characteristics (age, gender, type of cancer), caregiver characteristics (age, gender, employment status, relationship to patient, provided care, lived with care recipient), and psychological variables of family members (optimism, resilience, grief). Multivariate linear regression was used to examine the extent to which CANHELP total and subscale scores (dependent variables) were explained by the following independent variables: type of care setting, the same patient and family member characteristics as noted above, and the psychological variables of family members (optimism, resilience, grief) (research question #3). A p-value of <.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. For each dependent variable, a Pratt Index was computed to evaluate the relative importance of each independent variable [49]. The Pratt Index values represent the percentages of the explained variance in the dependent variable (i.e., the R-squared) that are attributable to each independent variable in the regression analysis.

Multiple imputation, using mean and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimation, was used to create 20 imputed data files with imputed values for missing data for variables that were included in the analysis (total missing was 0.9%). In addition, based on recommendations by Holman et al. [50] multiple imputation was used to impute the “not applicable” response category for the CANHELP items (total “not applicable” was 9.0%).

Results

In total, 712 of the 1254 patient death records screened over a 21 month period identified eligible family member participants. Of the 712 who were invited to participate, 558 agreed to have their name given to the project coordinator and were mailed the questionnaire. A total of 388 usable questionnaires were returned resulting in a response rate of 70% of surveys sent and 54% of eligible family members. Reasons for non-participation in the study from those who agreed to receive the questionnaire but did not return it included: being too busy to participate; not being interested; not wanting to re-live the experience; believing that the survey would be emotionally challenging; and believing that the majority of questions did not apply to their experience. Of the 388 family members who responded, 155 rated their satisfaction with PCUs, 140 with MCUs, 63 with ECUs, and 30 with ICUs.

Sample description by setting

Results pertaining to the comparison of demographic characteristics for both family members and patients (care recipients) across settings is provided in Table 1. There were several significant differences in demographic characteristics of care recipients and their family members across the four types of care settings (see Table 1 for details on distributions and statistical significance). Not surprisingly, the average age of care recipients was highest in the ECU setting (84.7 years) and care recipients in the ECU setting stayed much longer in care (92% stayed more than 34 days) than in any of the other settings. The shortest length of stay was in the ICU setting, with 58.6% of care recipients staying no more than 5 days. Care recipients in the ICU setting were younger (mean = 64.5 years on average) and less likely to be a relative (33.3%), relative to the other settings. Distributions of sex and age of family members were very similar across the four settings. Family members in the ICU setting were most likely to be a spouse (60.0%) of the care recipient, while family members from an ECU setting were most likely to have been caring for a parent/in-law (65.6%). The PCU setting had the highest percentage of family members (81.8%) who indicated “yes” in response to the question “Did you provide care?”. Care recipients in the PCU setting were much more likely to have cancer (72.9%) than in any of the other settings (ranging from 7.9% in the ECU to 21.4% in the MCU).

Table 1.

Sample description: care recipients and family members

| Total (n = 388) | ECU (n = 63) | ICU (n = 30) | MCU (n = 140) | PCU (n = 155) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care recipients | ||||||

| Age (years)/Mean(SD) (n = 384) | 78.4 (14.0) | 84.7b,d (14.1) | 64.5a,c,d (10.9) | 79.3b (13.9) | 77.5a,b (12.6) | .000 |

| Female (%) (n = 381) | 54.3 | 67.2b | 33.3a,c,d | 54.8b | 52.9b | .023 |

| Cancer (%) (n = 388) | 38.4 | 7.9c,d | 3.3c,d | 21.4a,b,d | 72.9a,b,c | .000 |

| Days on unit (%) (n = 379) | .000 | |||||

| Q1: <= 5 | 26.9 | 0.0b,c,d | 58.6a,c,d | 29.2a,b | 29.8a,b | |

| Q2: 5 to <= 11 | 23.5 | 1.6b,c,d | 24.1a | 24.8a | 31.1a | |

| Q3: 11 to <= 34 | 25.1 | 6.5c,d | 13.8c | 35.0a,b | 25.9a | |

| Q4: >34 | 24.5 | 92.0b,c,d | 3.4a | 10.9a | 13.2a | |

| Family members | ||||||

| Age (years)/Mean(SD) (n = 383) | 61.2 (12.9) | 63.6 (12.5) | 59.6 (12.9) | 60.5 (12.5) | 61.3 (13.4) | ns |

| Female (%) (n = 385) | 67.8 | 69.4 | 70.0 | 67.4 | 67.1 | ns |

| Married (%) (n = 385) | 65.5 | 77.4b,d | 53.3a | 68.8 | 60.0a | .035 |

| Caregiving for (%) (n = 383) | .000 | |||||

| Spouse | 35.8 | 21.3b,d | 60.0a,c | 28.5b,d | 43.2a,c | |

| Parent/in-law | 49.6 | 65.6b,d | 20.0a,c,d | 53.3b | 45.8a,b | |

| Other | 14.6 | 13.1 | 20.0 | 18.2 | 11.0 | |

| Working (%) (n = 381) | 43.8 | 50.0 | 40.0 | 46.0 | 40.3 | ns |

| Cared for care recipient (%) (n = 385) | 69.7 | 66.1b,d | 34.5a,c,d | 64.9b,d | 81.8a,b,c | .000 |

| Lived with care recipient (%) (n = 385) | 46.5 | 37.1b,d | 63.3a,c | 39.1b,d | 53.5a,c | .008 |

| Psychological variables | ||||||

| Optimism possible range of 0 to 4: Mean(SD) (n = 375) | 2.79 (0.64) | 2.78 (0.61) | 2.86 (0.71) | 2.87 (0.62) | 2.70 (0.64) | ns |

| Resilience possible range of 1 to 7: Mean(SD) (n = 379) | 5.73 (0.74) | 5.75 (0.69) | 5.70 (0.66) | 5.81 (0.61) | 5.66 (0.85) | ns |

| Grief possible range of 1 to 6: Mean(SD) (n = 369) | 4.64 (1.15) | 4.86a (1.08) | 4.03a,c (1.26) | 4.90b,d (1.03) | 4.43c (1.19) | .000 |

Note. Analyses based on non-imputed data. asignificant difference with ECU. bsignificant difference with ICU. csignificant difference with MCU. dsignificant difference with PCU. P-value is based on ANOVA for continuous variables and a chi-square test for categorical variables. ns not significant. Q quartile. SD standard deviation

CANHELP item, subscale and total scores by setting

The relative frequencies of responses for the 43 CANHELP items are presented in Fig. 1, which reveals several observable differences between the settings and room for improvement across all settings. Family members in the MCU setting were least satisfied with overall care, with 41% reporting being less than satisfied, whereas only 14% in the ICU reported being less than satisfied. The item that had the lowest satisfaction ratings in most of the settings was “you had enough time and energy to take care of yourself” (ranging from 61% to 66% of family members who reported not being satisfied). An example of notable differences between settings includes the relatively large percentages of family members in the ECU (56%), MCU (69%) and PCU (55%) who reported not being satisfied with the relief of emotional problems of the care recipient, such as depression.

Fig. 1.

Percentages of family members within settings who are less than “satisfied” for each CANHELP item. Note. % refers to the percentage of people who are not “satisfied” or “completely satisfied”.* “You participated with your relative or friend in discussions with the doctor relation to his/her end of life care and treatment plan”

Results pertaining to the mean comparison of CANHELP total and subscale scores across settings are reported in Table 2. Family in the MCU experienced statistically significant lower satisfaction overall (CANHELP total mean = 3.68) relative to any of the other settings (means of 3.92 [ECU], 4.12 [ICU], and 4.01 [PCU]; F(3371) = 8.30, p = .000). Comparisons of subscale scores across settings reveal that satisfaction was significantly greater in the PCU than MCU for “doctor and nurse care”, “illness management”, “health services”, and “communication and decision-making”. Satisfaction in the ICU and ECU also tended to be higher than in the MCU for several of the subscales (see Table 2 for statistical significance of different subscale comparisons). There were no statistically significant differences for any of the group comparisons on the “relationships” and “spirituality and meaning” subscales. “Spirituality and meaning” was the area of least satisfaction in all settings, ranging from 3.46 in the ICU to 3.81 in the PCU.

Table 2.

CANHELP scale and subscale means (SD) by setting adjusted for covariates

| ECU (n = 63) | ICU (n = 30) | MCU (n = 140) | PCU (n = 155) | Overall test F (3371), p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CANHELP (total) | 3.92(1.50)c | 4.12(2.30)c | 3.68(0.98)a,b,d | 4.01(1.04)c | 8.30, .000 |

| Doctor and nurse care | 3.87(1.97) | 4.07(3.03)c | 3.63(1.38)b,d | 4.01(1.38)c | 6.01, .000 |

| Illness management | 3.98(1.85)c | 4.26(2.82)c,d | 3.64(1.20)a,b,d | 3.94 (1.28)b,c | 8.39, .000 |

| Health services | 3.97(1.99)c | 4.17(3.43)c | 3.70(1.38)a,b,d | 4.09(1.38)c | 6.89, .001 |

| Communication | 3.96(1.93)b | 4.36(2.95)a,c | 3.74(1.26)b,d | 4.17(1.34)c | 9.76, .000 |

| Relationships | 3.83(1.60) | 3.94(2.48) | 3.80(1.08) | 3.88(1.12) | 2.64, .055 |

| Spirituality and meaning | 3.81(2.36) | 3.46(3.68) | 3.54(1.56) | 3.81(1.63) | 2.64, .059 |

Note. ANCOVA results for each CANHELP scale based on averages across 20 imputations. All means are adjusted for patient characteristics (age, gender, diagnosis (cancer vs. not cancer)), caregiver characteristics (age, gender, employment status, relationship to patient, provided care, lived with care recipient), and psychological variables of family members (optimism, resilience, grief).astatistically significant difference (p < .05) with ECU. bstatistically significant difference with ICU. cstatistically significant difference with MCU. dstatistically significant difference with PCU

Prediction of CANHELP total and subscale scores

The regression model including all independent variables explained 18.9% of the variance in the CANHELP total scale, and between 11.8% and 27.8% of the variance in the subscales (see Table 3). The partitioning of the explained variance is shown in Fig. 2. Most of the explained variance in the CANHELP total score was attributable to the setting of care (Pratt Index = 44%), notably receiving care in the MCU versus the PCU, and psychological characteristics of family members (Pratt Index = 41%). In particular, a one-point lower score in resilience (on a scale from 1 to 7) was associated with an average relative decrease of 0.21 in the total score (on a scale from 1 to 5). These results were similar for the “illness management” subscale, with a relative decrease of 0.18. Resilience of family caregivers also accounted for most of the explained variance in the “relationships with others” (75% of the explained variance) and “spirituality and meaning” subscales (76% of the explained variance). However, optimism was associated only with “illness management” and “spirituality and meaning” (regression coefficients of 0.15, and 0.23, respectively), and grief was associated only with “relationships with others” and “spirituality and meaning”; one-point higher score on the TRIG (i.e., less grief) was associated with a relative increase of 0.11 for both of these subscale scores. Family member characteristics (notably “employment status”), accounted for most of the explained variance in “health services characteristics” (39% of the explained variance), where family members who are employed had scores that were 0.29 points lower than those who were not employed.

Table 3.

Multivariate regression analysis

| Independent variables | CANHELP Total | Characteristics of doctors and nurses | Illness management | Health services characteristics | Communication and decision making | Relationships with others | Spirituality and meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care setting (ref = palliative) | |||||||

| ECU | −0.10 | −0.15 | 0.04 | −0.13 | −0.21 | −0.06 | 0.00 |

| ICU | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.06 | −0.35 |

| MCU | −0.33* | −0.39* | −0.30* | −0.39* | −0.43* | −0.08 | −0.27* |

| Care recipient characteristics | |||||||

| Age (years) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Gender (ref = male) | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| Diagnosis (cancer versus not)a | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.19 | −0.07 | 0.02 | −0.07 |

| Family member characteristics | |||||||

| Age (years) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01* | 0.00 |

| Gender (ref = male) | −0.10 | −0.14 | −0.15 | −0.03 | −0.19* | 0.06 | 0.10 |

| Employment statusa | −0.12 | −0.07 | −0.14 | −0.29* | −0.10 | −0.09 | −0.12 |

| Relationship to patient | |||||||

| Husband/wife (ref = ‘other’) | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.19 | −0.01 | −0.14 | −0.10 |

| Parent/parent in law (ref = ‘other’) | −0.09 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.22 | −0.22 | −0.09 |

| Provided carea | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.24* | −0.02 | 0.09 |

| Lived with care recipienta | −0.10 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.20 | −0.31* | −0.02 |

| Psychological variables of family members | |||||||

| Optimism (possible range of 0 to 4) | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.15* | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.23* |

| Resilience (possible range of 1 to 7) | 0.21* | 0.20* | 0.18* | 0.14* | 0.22* | 0.25* | 0.27* |

| Grief (possible range of 1 to 6) | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.11* | 0.11* |

| R-square | 18.90% | 11.80% | 14.10% | 16.20% | 15.30% | 27.80% | 19.50% |

Note. Unstandardized regression coefficients. ayes versus no (referent). *p < .05 (bolded values)

Fig. 2.

Relative importance of combined independent variables predicting CANHELP. Note. Pratt Index was used to compute relative importance as the percentages of explained variance attributable to variability in care settings (ECU, ICU, MCU, PCU), patient characteristics (age, gender, diagnosis (cancer vs. not cancer)), caregiver characteristics (age, gender, employment status, relationship to patient, provided care, lived with care recipient), and psychological variables of family members (optimism, resilience, grief)

Discussion

The overall aim of this study was to gain a better understanding of how bereaved family members perceive the quality of EOL care based on where the patient has died. While findings suggest that there is room for improvement across all settings of care, the findings particularly reveal the need for greater efforts towards improving the quality of EOL care provided in acute care medical units. This is consistent with results from other studies, which indicate that up to 35% of all hospital inpatients have palliative care needs [21, 24, 51] with these needs going largely unaddressed in acute care; patients and families report poor quality care, characterized by aggressive therapies, unnecessary pain, and depersonalized practices by providers [22, 52–56]. While resource constraints, including the absence of specialized palliative care consultation services may be one factor explaining lower overall satisfaction with acute care for bereaved family members in this study, the tendency toward curative and treatment-oriented care in acute care, and a lack of integration of palliative care approaches to care [57, 58] may also play a role. Gott et al. [59] explored how transitions to a palliative approach are managed in acute care, citing challenges such as lack of discussion with patients about prognosis and communication difficulties among team members as barriers. Indeed, in the present study, 56% of family members in acute care were not satisfied with participation in decision-making. Other research points to communication breakdowns among the interprofessional team and differing perspectives among nursing and medical staff on what constitutes quality of care for people with chronic life-limiting illnesses [60]. Additionally, a prevailing belief that dying patients “don’t belong” in acute care [60, 61] can sometimes direct providers’ attention toward a desire to discharge these patients to palliative care services instead of considering the important role that acute care medical units have in the care of the dying.

As acute care still functions as a major provider of EOL care in Canada and elsewhere [1–4], improving the quality of EOL care should be a priority, both for cancer patients - the more traditional recipients of palliative care - and for the larger population of people with life-limiting conditions such as those with advancing heart, lung and kidney disease, frailty and dementias. Integration of a palliative approach has been cited as one possible solution [57, 62, 63], but a lack of conceptual clarity about what is meant by a palliative approach hampers widespread application. Yet, a palliative approach, which involves building the capacity of providers who do not specialize in palliative care to adopt adopt the foundational principles of palliative care, adapt palliative care knowledge and expertise to the illness trajectories of people with chronic life-limiting conditions other than cancer, and embed this adapted knowledge “upstream” into the delivery of care across care settings [57], requires consideration if improvements for the dying in acute care are to be achieved. Interventions such as using the “individualized” version of the CANHELP on medical teaching units is another promising improvement strategy to be considered if we are to achieve improvements in EOL care in these settings [64].

Despite the fact that family members were generally satisfied with the quality of care in the PCUs, findings suggest that there is room for improvement in areas that PCUs aim to excel. We might have expected to see higher satisfaction scores for all of the CANHELP subscales given the emphasis in palliative care on communication, decision making, symptom management and attention to psychosocial and spiritual concerns. Though illness management was the only subscale with a statistically significant difference in family member ratings between PCUs and ICUs, ICU ratings were observed to be higher for all but one subscale. Perhaps this is not surprising given that the ICU environment tends to have higher staffing ratios than most inpatient settings [65, 66]. At the same time, ICU is an environment that is highly technical, institutionalized, and where staff have not traditionally been exposed to much formal palliative care training [67, 68]. The lower than expected PCU scores run counterintuitive to clinical reports where families in palliative care report how deeply grateful they are for the care, services and support provided [31, 69]. However, it may be that our study of bereaved family members provides us with a different picture of their perceptions of care quality. Some reports suggest that family members are sometimes reluctant to be critical of palliative care services when the patient is alive because they do not want their complaints conceived as being non-appreciative of care and support or they do not want their critical comments to influence care that the patient receives [70, 71]. This is consistent with the work of the Picker Institute in the United Kingdom that has shown that real time satisfaction scores tend to be more favorable than retrospective scores and may lead to the conclusion that quality of care is better than it really is [72].

Finally, as Fig. 2 reveals, psychological variables and type of setting accounted for most of the explained variances in the CANHELP subscales and total score. That is, while psychological variables, mainly resilience of family members, play an important role in perceptions of the quality of EOL care, the type of care setting in which EOL care occurs, and several other characteristics of family members (e.g., their employment status, whether they provide care, and whether they live with the care recipient), are also important considerations in how bereaved family members appraise the quality of EOL care. These findings are not unexpected but point to some possible sites for targeted intervention. For example, acute care hospital interventions such as advance care planning has been shown to improve EOL care, enhance patient and family satisfaction and reduce stress, anxiety and depression among surviving relatives [73]. Likewise, research on resilience is being used to design interventions in other populations (i.e., helping families cope with a parent with a depressive disorder) and that may have applicability to supporting families in EOL care situations [74]. Focused attention on improving the delivery of high quality EOL care in all inpatient settings and on supporting families should be a goal for health system managers and administrators. The aging of the population along with increasing numbers of people diagnosed with chronic life-limiting illnesses will necessitate expansion or revision of existing services to meet the needs for EOL care, at least into the foreseeable future. Home care is often cited as the current solution to meet rising needs for palliative care [75, 76] and is reported to be the place where most people would prefer to be cared for and die [77–80]. However, without substantive investments in home-based palliative care it is unclear how this goal will be achieved or even sustained without adding significant cost to an already fragile system [75, 81] especially without shifting the financial burden to families [82]. Further, while findings not surprisingly suggest that resilient people are more likely to be satisfied with their care, there is a concurrent concern that resiliency may mask the very real quality of care and systemic issues that prevent excellent EOL care from occurring in inpatient settings. Research has shown that lack of knowledge of how to complain, low expectations, feelings of gratitude, fear of retribution and deference to health professionals may mask the problems patients and families face in receiving quality care [83–85]. Indeed, analyses of qualitative data collected for this study and published elsewhere [86] suggests that family members sometimes rationalize negative care experiences as an unavoidable reality within a constrained health care system, excusing front-line staff and the larger health care system from responsibility when undesirable care occurs.

Limitations

Study findings should be considered in light of the fact that data are limited to one health region and the findings are undoubtedly influenced by the particular health service context and resource base available. In addition, there are small sample sizes within several of the settings though this is somewhat mitigated by a relatively good response rate among settings. Only English speaking people were surveyed and in a health region where English is the dominant language. Perceptions of care quality may differ in bereaved family membes with culturally and linguistically different backgrounds. Despite these limitations, the study raises some important questions in need of further exploration.

Conclusion

Improving care at the EOL is a key policy direction to improve the quality of life for patients facing life-limiting conditions and their family members [87–89]. Understanding how quality of care is perceived by family members across inpatient care settings is one way to determine specific domains of care that are in need of improvement and to begin to address barriers to quality care. Although enhancing quality of EOL care is important in all settings, this study adds to the increasing body of evidence suggesting a critical need to focus on improvements in acute care, and suggests that care provided in palliative care units might also require attention.

Acknowledgements

At the time of this study Dr. Stajduhar was supported by investigator awards from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. The authors gratefully acknowledge bereaved family members who participated in the study.

aThe CANHELP questionnaire was designed to evaluate satisfaction with care for older patients with life threatening illnesses, and their family members. Details can be found at the Canadian Reserachers at the End of Life Network (CARENET) website [90].

Funding

This research was funded by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR). The funder had no role in study design; the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANCOVA

Analysis of covariance

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- CANHELP

Canadian health care evaluation project

- ECU

Extended care unit

- EOL

End of life

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- MCU

Medical care unit

- PCU

Palliative care unit

- TRIG

Texas revised inventory of grief

Authors’ contributions

KS led all aspects of the study. KS, RC, DH, DA, DB and LN were involved in overall study design. RS led data analysis with contributions from AG, KS, DA, RC and DH. All authors contributed to interpretation of findings. KS, RS, and AG drafted the initial manuscript and all other authors provided ongoing feedback throughout manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted by the joint University of Victoria and Vancouver Island Health Authority Subcommittee for Health Research Ethics Board. All participants provided written informed consent prior to data collection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kelli Stajduhar, Email: kis@uvic.ca.

Richard Sawatzky, Email: Rick.Sawatzky@twu.ca.

S. Robin Cohen, Email: robin.cohen@mcgill.ca

Daren K. Heyland, Email: dkh2@queensu.ca

Diane Allan, Email: diane.bomans@usask.ca.

Darcee Bidgood, Email: bidgood@me.com.

Leah Norgrove, Email: leah.norgrove@viha.ca.

Anne M. Gadermann, Email: anne.gadermann@ubc.ca

References

- 1.Bekelman JE, Halpern SD, Blankart CR, Bynum JP, Cohen J, Fowler R, et al. Comparison of site of death, health care utilization, and hospital expenditures for patients dying with cancer in 7 developed countries. JAMA. 2016;315:272–283. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Health care use at the end of life in western Canada. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Statistics Canada . Deaths in hospitals and elsewhere, Canada, provinces and territories. (table 102–0509) 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heyland DK, Lavery JV, Tranmer JE, Shortt SE, Taylor SJ. Dying in Canada: is it an institutionalized, technologically supported experience? J Palliat Care. 2000;16(Suppl):S10–S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broad JB, Gott M, Kim H, Boyd M, Chen H, Connolly MJ. Where do people die? An international comparison of the percentage of deaths occurring in hospital and residential aged care settings in 45 populations, using published and available statistics. Int J Public Health. 2013;58:257–267. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0394-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandsdalen T, Grondahl VA, Hov R, Hoye S, Rystedt I, Wilde-Larsson B. Patients’ perceptions of palliative care quality in hospice inpatient care, hospice day care, palliative units in nursing homes, and home care: a cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:79. doi: 10.1186/s12904-016-0152-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell CL, Baernholdt M, Yan G, Hinton ID, Lewis E. Racial/ethnic perspectives on the quality of hospice care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30:347–353. doi: 10.1177/1049909112457455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhodes RL, Mitchell SL, Miller SC, Connor SR, Teno JM. Bereaved family members’ evaluation of hospice care: what factors influence overall satisfaction with services? J Pain Symptom Manag. 2008;35:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aslakson RA, Curtis JR, Nelson JE. The changing role of palliative care in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:2418–2428. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Hopper SS, Ortiz JM, Whang C, Morrison RS. Does palliative care have a future in the emergency department? Discussions with attending emergency physicians. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2012;43:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heyland DK, Rocker GM, O'Callaghan CJ, Dodek PM, Cook DJ. Dying in the ICU: perspectives of family members. Chest. 2003;124:392–397. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.1.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heyland DK, Dodek P, Rocker G, Groll D, Gafni A, Pichora D, et al. What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ. 2006;174:627–633. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck I, Tornquist A, Brostrom L, Edberg AK. Having to focus on doing rather than being-nurse assistants’ experience of palliative care in municipal residential care settings. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah SM, Carey IM, Harris T, DeWilde S, Victor CR, Cook DG. The mental health and mortality impact of death of a partner with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31:929–937. doi: 10.1002/gps.4411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McVey P, McKenzie H, White K. A community-of-care: the integration of a palliative approach within residential aged care facilities in Australia. Health Soc Care Community. 2014;22:197–209. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Mahony S, McHenry J, Blank AE, Snow D, Eti Karakas S, Santoro G, et al. Preliminary report of the integration of a palliative care team into an intensive care unit. Palliat Med. 2010;24:154–165. doi: 10.1177/0269216309346540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyashita M, Morita T, Sato K, Tsuneto S, Shima Y. A Nationwide survey of quality of end-of-life cancer Care in Designated Cancer Centers, inpatient palliative care units, and home hospices in Japan: the J-HOPE study. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2015;50:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, Welch LC, Wetle T, Shield R, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291:88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tolle SW, Tilden VP, Rosenfeld AG, Hickman SE. Family reports of barriers to optimal care of the dying. Nurs Res. 2000;49:310–317. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200011000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stajduhar KI, Davies B. Palliative care at home: reflections on HIV/AIDS family caregiving experiences. J Palliat Care. 1998;14:14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Virdun C, Luckett T, Davidson PM, Phillips J. Dying in the hospital setting: a systematic review of quantitative studies identifying the elements of end-of-life care that patients and their families rank as being most important. Palliat Med. 2015;29:774–796. doi: 10.1177/0269216315583032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stajduhar KI, Davies B. Variations in and factors influencing family members’ decisions for palliative home care. Palliat Med. 2005;19:21–32. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm963oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson GN, McClement SE, Menec VH, Chochinov HM. Understanding bereaved family members’ dissatisfaction with end-of-life care in nursing homes. J Gerontol Nurs. 2012;38:49–60. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20120906-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bussmann S, Muders P, Zahrt-Omar CA, Escobar PL, Claus M, Schildmann J, et al. Improving end-of-life care in hospitals: a qualitative analysis of bereaved families’ experiences and suggestions. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;32:44–51. doi: 10.1177/1049909113512718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearce MJ, Chen J, Silverman GK, Kasl SV, Rosenheck R, Prigerson HG. Religious coping, health, and health service use among bereaved adults. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2002;32:179–199. doi: 10.2190/UNE0-EFAN-XPNJ-9N3G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patten SB, Beck C. Major depression and mental health care utilization in Canada: 1994 to 2000. Can J Psychiatr. 2004;49:303–309. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guldin MB, Jensen AB, Zachariae R, Vedsted P. Healthcare utilization of bereaved relatives of patients who died from cancer. A national population-based study. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1152–1158. doi: 10.1002/pon.3120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kapari M, Addington-Hall J, Hotopf M. Risk factors for common mental disorder in caregiving and bereavement. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2010;40:844–856. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guerriere D, Husain A, Zagorski B, Marshall D, Seow H, Brazil K, et al. Predictors of caregiver burden across the home-based palliative care trajectory in Ontario, Canada. Health Soc Care Community. 2016;24:428–438. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guerriere DN, Zagorski B, Coyte PC. Family caregiver satisfaction with home-based nursing and physician care over the palliative care trajectory: results from a longitudinal survey questionnaire. Palliat Med. 2013;27:632–638. doi: 10.1177/0269216312473171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergeman CA, Wallace KA. Resiliency in later life. In: Whitman TL, Merluzzi TV, White RD, editors. Life-span perspectives on health and illness. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Optimism, pessimism, and psychological well-being. In: Chang EC, editor. Optimism and pessimism: implications for theory, research and practice. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Given CW, Stommel M, Given B, Osuch J, Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC. The influence of cancer patients’ symptoms and functional states on patients’ depression and family caregivers’ reaction and depression. Health Psychol. 1993;12:277–285. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.12.4.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Given CW, Given B. Predictors of postbereavement depressive symptomatology among family caregivers of cancer patients. Suppor Care Cancer. 1997;5:53–60. doi: 10.1007/BF01681962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blanchard CG, Albrecht TL, Ruckdeschel JC. The crisis of cancer: psychological impact on family caregivers. Oncology (Williston Park) 1997;11:189–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:7–18. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Health care use at the end of life in Atlantic Canada. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heyland DK, Groll D, Rocker G, Dodek P, Gafni A, Tranmer J, et al. End-of-life care in acute care hospitals in Canada: a quality finish? J Palliat Care. 2005;21:142–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, Kutsogiannis DJ, Skrobik Y, et al. The development and validation of a novel questionnaire to measure patient and family satisfaction with end-of-life care: the Canadian health care evaluation project (CANHELP) questionnaire. Palliat Med. 2010;24:682–695. doi: 10.1177/0269216310373168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zumbo BD, Gadermann AM, Zeisser C. Ordinal versions of coefficients alpha and theta for Likert rating scales. JMASM. 2007;6:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zisook S, Devaul RA, Click MA. Measuring symptoms of grief and bereavement. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1590–1593. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.12.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Montano SA, Lewey JH, O'Toole SK, Graves D. Reliability generalization of the Texas revised inventory of grief (TRIG) Death Stud. 2016;40:256–262. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2015.1129370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the life orientation test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Segerstrom SC, Evans DR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA. Optimism and pessimism dimensions in the life orientation test-revised: method and meaning. J Res Pers. 2011;45:126–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagnild GM, Young HM. Development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale. J Nurs Meas. 1993;1:165–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wagnild G. A review of the resilience scale. J Nurs Meas. 2009;17:105–113. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.17.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Windle G, Bennett KM, Noyes J. A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas DR, Hughes E, Zumbo BD. On variable importance in linear regression. Soc Indic Res. 1998;45:253–275. doi: 10.1023/A:1006954016433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holman R, Glas CA, Lindeboom R, Zwinderman AH, de Haan RJ. Practical methods for dealing with ‘not applicable’ item responses in the AMC linear disability score project. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:29. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sigurdardottir KR, Haugen DF. Prevalence of distressing symptoms in hospitalised patients on medical wards: a cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care. 2008;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fortin ML, Bouchard L. Caring for persons at the end of life in a curative care unit: privileges and heartbreaks. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2009;19:110–116. doi: 10.5737/1181912x193110116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gelinas C, Fillion L, Robitaille MA, Truchon M. Stressors experienced by nurses providing end-of-life palliative care in the intensive care unit. Can J Nurs Res. 2012;44:18–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robinson J, Gott M, Ingleton C. Patient and family experiences of palliative care in hospital: what do we know? An integrative review. Palliat Med. 2014;28:18–33. doi: 10.1177/0269216313487568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodriguez KL, Barnato AE, Arnold RM. Perceptions and utilization of palliative care services in acute care hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:99–110. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schenker Y, Arnold R. The next era of palliative care. JAMA. 2015;314:1565–1566. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.11217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sawatzky R, Porterfield P, Lee J, Dixon D, Lounsbury K, Pesut B, et al. Conceptual foundations of a palliative approach: a knowledge synthesis. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:5. doi: 10.1186/s12904-016-0076-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stajduhar KI. Chronic illness, palliative care, and the problematic nature of dying. Can J Nurs Res. 2011;43:7–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gott M, Ingleton C, Bennett MI, Gardiner C. Transitions to palliative care in acute hospitals in England: qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2011;1:42–48. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stajduhar K, Doane G. The last best place to die: provider perspectives on dying in acute care. J Palliat Care. 2014;30:214–215. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chan L. Dying people don’t belong here: how cultural aspects of the acute medical ward shape care of the dying. McGill University, Montreal: Doctoral Thesis; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sawatzky R, Porterfield P, Roberts D, Lee J, Liang L, Reimer-Kirkham S, et al. Embedding a palliative approach in nursing care delivery: an integrated knowledge synthesis. ANS. 2017;40:263–279. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stajduhar KI, Tayler C. Taking an “upstream” approach in the care of dying cancer patients: the case for a palliative approach. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2014;24:144–153. doi: 10.5737/1181912x241144148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Frank C, Touw M, Suurdt J, Jiang X, Wattam P, Heyland DK. Optimizing end-of-life care on medical clinical teaching units using the CANHELP questionnaire and a nurse facilitator: a feasibility-study. Can J Nurs Res. 2012;44:41–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kleinpell RM. ICU workforce: revisiting nurse staffing. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:1291–1292. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Penoyer DA. Nurse staffing and patient outcomes in critical care: a concise review. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1521–1528. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e47888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adesina O, DeBellis A, Zannettino L. Third-year Australian nursing students’ attitudes, experiences, knowledge, and education concerning end-of-life care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2014;20:395–401. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2014.20.8.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zheng RS, Lee SF, Bloomer MJ. How new graduate nurses experience patient death: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;53:320–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McRae S, Caty S, Nelder M, Picard L. Palliative care on Manitoulin Island. Views of family caregivers in remote communities. Can Fam Physician. 2000;46:1301–1307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Canada H. The information needs of informal caregivers involved in providing support to a critically ill loved one. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sinding C. Disarmed complaints: unpacking satisfaction with end-of-life care. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:1375–1385. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00512-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sizmur S, Graham C, Walsh J. Influence of patients’ age and sex and the mode of administration on results from the NHS friends and family test of patient experience. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2015;20:5–10. doi: 10.1177/1355819614536887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lutha SS, Cicchetti D. The construct of resilience: implications for interventions and social policies. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12:857–885. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400004156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Supporting informal caregivers – the heart of home care. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 76.The Change Foundation . Because this is the rainy day: a discussion paper on home care and informal caregiving for seniors with chronic health conditions. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beccaro M, Costantini M, Giorgi Rossi P, Miccinesi G, Grimaldi M, Bruzzi P, et al. Actual and preferred place of death of cancer patients. Results from the Italian survey of the dying of cancer (ISDOC) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:412–416. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.043646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, McCrone P, Higginson IJ. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; doi: 10.1002/14651858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Gysels M, Hall S, Higginson IJ. Heterogeneity and changes in preferences for dying at home: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-12-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Holm M, Henriksson A, Carlander I, Wengstrom Y, Ohlen J. Preparing for family caregiving in specialized palliative home care: an ongoing process. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13:767–775. doi: 10.1017/S1478951514000558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McBride T, Morton A, Nichols A, van Stolk C. Comparing the costs of alternative models of end-of-life care. J Palliat Care. 2011;27:126–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dumont S, Jacobs P, Fassbender K, Anderson D, Turcotte V, Harel F. Costs associated with resource utilization during the palliative phase of care: a Canadian perspective. Palliat Med. 2009;23:708–717. doi: 10.1177/0269216309346546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McIlfatrick S. Assessing palliative care needs: views of patients, informal carers and healthcare professionals. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57:77–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yamin AE. Suffering and powerlessness: the significance of promoting participation in rights-based approaches to health. Health Hum Rights. 2009;11:5–22. doi: 10.2307/40285214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Funk LM, Stajduhar KI, Robin Cohen S, Heyland DK, Williams A. Legitimising and rationalising in talk about satisfaction with formal healthcare among bereaved family members. Sociol Health Illn. 2012;34:1010–1024. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Carstairs S. Still not there - quality end-of-life care: a progress report. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Institute of Medicine . Committee on approaching death: addressing key end-of-life issues issues. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Government of Western Australia . Department of Healht. The end-of-life framework: a statewide model for the provision of comprehensive, coordinated care at end-of-life in western Australia. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network (CARENET). Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project Questionnaire. http://www.thecarenet.ca/28-researchers/our-projects/canhelp-questionnaire. Accessed 29 Mar 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.