Abstract

Introduction

Many autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), share common mechanisms; however, population-based studies of the magnitude of multiple autoimmune diseases in patients with RA have not been performed.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study using a US administrative healthcare thcare claims database to screen for prevalence of multiple autoimmune diseases in patients with RA and osteoarthritis (OA). Each patient diagnosed with RA between January 1, 2006 and September 30, 2014 was age- and sex-matched with five patients with OA. The prevalence of 37 pre-specified autoimmune diseases during the 24-month period before and after RA or OA diagnosis was compared.

Results

Overall, 286,601 patients with RA and 992,838 matched patients (from 1,421,624 records) with OA were evaluated. During the baseline period, at least one and more than one autoimmune diseases were identified in 24.3% and 6.0% of patients with RA compared with 10.5% and 1.4% of patients with OA, respectively. Highest prevalence rates for patients with RA were for systemic lupus erythematosus (3.8% versus 0.7% for OA) and psoriatic arthritis (3.2% versus 0.4%). Highest odds ratios (ORs) comparing RA with OA were for the prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis (OR 8.0; 95% CI 7.6, 8.5) and psoriatic arthritis (OR 7.8; 95% CI 7.6, 8.1).

Conclusion

Patients with RA have more concurrent autoimmune diseases than patients with OA. These data suggest that the interrelationship between RA and other autoimmune diseases, and outcomes associated with the occurrence of multiple autoimmune diseases, may play an important role in disease understanding, management, and treatment decisions.

Funding

Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-017-0627-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Autoimmune diseases, Co-existence, Cross-sectional, Prevalence, Rheumatology, Rheumatoid arthritis

Introduction

The estimated prevalence of autoimmune diseases in Europe [1] and the USA [2] is 5.3% and 3.2%, respectively, which equates to 23.5 million people affected in the USA (based on 24 autoimmune diseases for which good epidemiologic studies are available) [3, 4]. However, the American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association predicts (taking all autoimmune diseases into account) that there are up to 50 million people in the USA affected by an autoimmune disease [3]. Those with autoimmune diseases have an associated increase in morbidity and mortality, and autoimmune diseases are among the 10 leading causes of death (under 65 years) [5] and disability for women in the USA [6]. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a chronic, systemic, inflammatory disorder with a worldwide prevalence of 0.5–1%, is part of a heterogeneous group of 80–100 known autoimmune diseases [3].

Many autoimmune diseases, including RA, share common pathogenic mechanisms, cytokine pathways, and a systemic inflammatory cascade [7]. Genome-wide association studies have helped expand the understanding of these shared pathways, their genetic basis (including shared loci), and the common environmental risk factors of autoimmune diseases [7, 8]. The misdirected immune response against self that is observed in these diseases involves multiple body systems, often resulting in overlapping syndromes. On average, patients with RA have two or more comorbid conditions [5]. The presence of other autoimmune diseases in patients with RA can lead to increases in both disability and mortality [5, 9]. In addition, some autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and psoriasis, can arise or be exacerbated as a result of treatments for RA [10].

At present, there are few published studies quantifying the occurrence of overlapping autoimmune diseases in patients with RA. Most published papers are case reports or clinical/hospital studies involving one or a selected few autoimmune diseases [11–20]. To the best of our knowledge, there is currently no evaluation of the occurrence of multiple autoimmune diseases in patients with RA. This large, cross-sectional study was performed to screen for and evaluate the occurrence of multiple pre-specified autoimmune diseases in an RA population. To address potential observation bias, the occurrence of multiple pre-specified autoimmune diseases was evaluated in patients with osteoarthritis (OA), a population with a similar number of healthcare encounters to the RA group.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a cross-sectional study with two US administrative healthcare claims databases: the Truven Health MarketScan® Commercial Database and the Medicare Supplemental Database. We used the Commercial Database with information dating from 2006 on over 70 million privately insured patients under 65 years and the Medicare Supplemental Database with information dating from 2006 on 6 million patients over 65 years of age who receive Medicare coverage. The Commercial Database is projectable to the US population and the Medicare Supplemental Database is projectable to the US population with Medicare supplemental insurance. A preliminary examination of the Truven Health MarketScan® data suggested that combining both databases would generate approximately 200,000 patients with RA.

Analyses were conducted using a common data model version of these databases. This format standardizes the data structure and terminologies, minimizing the need for customizations and allowing the proposed analytic methods to be applied systematically, thus making any cross-database analyses more meaningful [21].

The study was conducted in accordance with the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices [22], applicable regulatory requirements, and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. Review and approval by ethics committees and patient informed consent were not required for this study.

Patients

RA Group

Eligible patients with RA were required to have at least two inpatient or outpatient physician International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes of 714.xx within 90 days of each other at any time during the study period. This criterion for RA was based on MacLean’s algorithm for the identification of RA using administrative claims data [23]. Patients meeting the MacLean’s criterion of RA between January 1, 2006 and September 30, 2014 were identified and included in the study.

OA Group

A disease-comparison group included patients diagnosed with at least two ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes for OA (715.xx) within 90 days of each other between January 1, 2006 and September 30, 2014.

The index date for both groups is the date of the second of the two claims with the specified diagnosis codes. All patients with at least 365 days of continuous health plan enrollment before and after their qualifying RA or OA diagnosis date (index date) were included. For each patient with RA, five age-matched (± 5 years) and sex-matched patients with OA were identified. Patients with both OA and RA (two diagnosis codes in the 365 days before and after their qualifying diagnosis) were excluded.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the populations of patients with RA and OA. Demographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [24], calendar time, and number of healthcare encounters were evaluated. The CCI was calculated both with and without rheumatic disease as a component (Supplementary Table 1).

We calculated prevalence rates for all autoimmune diseases with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the matched RA and OA populations. Matched prevalence rates and odds ratios (ORs; univariate analysis, RA cohort with OA cohort as reference) with 95% CIs were computed for patients who had two ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes (Supplementary Table 2) for any of the 37 pre-specified autoimmune diseases (within the 365 days before and after the qualifying RA or OA diagnosis).

Results

Patient Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

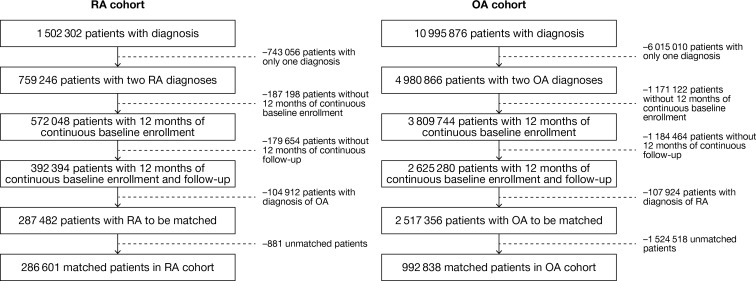

A total of 5252 patients with both RA and OA diagnoses were excluded. A total of 286,601 patients with RA and 992,838 matched patients (from 1,421,624 records) with OA were evaluated (Fig. 1). More patients with RA (31.5%) were diagnosed by a rheumatologist than patients with OA (0.8%).

Fig. 1.

RA and OA patient populations before and after age and sex matching. The age and sex of those patients excluded without two diagnoses for either RA or OA and those without adequate length of baseline or follow-up were similar to those included in the study (data not shown). RA rheumatoid arthritis, OA osteoarthritis

Across both cohorts, approximately three-quarters of the patients were female (74%), with a mean age of 54 years (Table 1). The comorbidities recorded and hospital visits (inpatient/emergency room) were generally similar between patients with RA and OA, suggesting a similar healthcare encounter profile (Table 1). However, some differences were noted: patients with OA were more likely to have hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and asthma, and patients with RA to have a slight increase in occurrence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Some treatment differences were also noted: patients with RA were more likely to be treated with biologic and non-biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, methotrexate, and corticosteroids than those with OA (Table 1). The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs differed slightly between both groups (RA 42.8% versus OA 41.8%).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics of the RA and matched OA groups

| Characteristic | RA N = 286,601 |

OA (matched) N = 1,421,624a |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female, n (%) | 212,751 (74.2) | 1,055,736 (74.3) | 0.264 |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 53.2 (15.6) | 54.0 (14.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Autoimmune diseases, n (%)b | |||

| 0 | 217,020 (75.7) | 1,272,548 (89.5) | < 0.0001 |

| 1 | 52,487 (18.3) | 128,886 (9.1) | < 0.0001 |

| 2 | 13,361 (4.7) | 16,969 (1.2) | < 0.0001 |

| 3 | 2893 (1.0) | 2670 (0.2) | < 0.0001 |

| > 3 | 840 (0.3) | 551 (0.04) | < 0.0001 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | 104,968 (36.6) | 630,415 (44.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 100,228 (35.0) | 606,061 (42.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 79,698 (27.8) | 399,719 (28.1) | 0.0011 |

| Diabetes | 36,438 (12.7) | 224,476 (15.8) | < 0.0001 |

| COPD | 24,458 (8.5) | 102,917 (7.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Asthma | 21,915 (7.7) | 120,902 (8.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Malignancy | 21,644 (7.6) | 107,812 (7.6) | 1.000 |

| Medication, n (%) | |||

| Biologic DMARDs | 56,781 (19.8) | 5548 (0.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Non-biologic DMARDs | 126,442 (44.1) | 34,408 (2.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Methotrexate | 83,144 (29.0) | 5203 (0.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Corticosteroids | 133,568 (46.6) | 432,798 (30.4) | < 0.0001 |

| NSAIDs | 122,608 (42.8) | 594,439 (41.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Inpatient hospital visits, mean (SD) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.5) | 1.000 |

| Outpatient hospital visits, mean (SD) | 18.6 (15.9) | 19.4 (17.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Emergency room visits, mean (SD) | 0.5 (1.3) | 0.5 (1.5) | 1.000 |

| CCI score, mean (SD)c | 1.6 (1.4) | 0.8 (1.4) | < 0.0001 |

| CCI score without considering rheumatic disease, mean (SD)c | 0.7 (1.4) | 0.8 (1.4) | < 0.0001 |

RA rheumatoid arthritis, OA osteoarthritis, SD standard deviation, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, DMARD disease-modifying antirheumatic drug, NSAID nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, CCI Charlson Comorbidity Index, calculated by addition of comorbidities

aRecords for 992,838 patients

bMyositis diagnosis codes included in baseline autoimmune disease evaluation

cThe CCI contains 17 categories of comorbidities and predicts the 10-year mortality for a patient who may have a range of comorbid conditions. Each condition is assigned a score of 1, 2, 3, or 6, depending on the risk of dying associated with this condition [24]

Importantly, the number of other autoimmune diseases identified was greater among patients with RA [24.3% (having a least one) and 6.0% (having more than one)] compared with patients with OA (10.5% and 1.4%, respectively; Table 1).

Prevalence

Overall, the prevalence rates of the pre-specified autoimmune diseases evaluated were higher among patients with RA than among the matched patients with OA (Table 2). Leukocytoclastic vasculitis had the lowest prevalence in both the RA and OA groups (0.05% versus 0.01%, respectively). The prevalence rates of other specific conditions differed between the two groups. For patients with RA, SLE (3.8%) and psoriatic arthritis (3.2%) were the most prevalent, while type 1 diabetes mellitus (1.7%) and psoriasis (0.9%) were the most prevalent for matched patients with OA.

Table 2.

Prevalence rates and odds ratios for the 37 pre-specified autoimmune diseases using two diagnosis codes

| Autoimmune disease | RA, % | OA, % | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 3.78 | 0.69 | 5.7 (5.5, 5.8) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 3.16 | 0.42 | 7.8 (7.6, 8.1) |

| Sjögren’s/sicca syndrome | 2.42 | 0.36 | 6.8 (6.6, 7.1) |

| Psoriasis only | 1.86 | 0.85 | 2.2 (2.1, 2.3) |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus | 1.83 | 1.74 | 1.1 (1.0, 1.1) |

| Interstitial lung disease/pulmonary fibrosis | 1.52 | 0.31 | 4.9 (4.7, 5.2) |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | 1.39 | 0.34 | 4.1 (3.9, 4.3) |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 1.16 | 0.15 | 8.0 (7.6, 8.5) |

| Crohn’s disease | 1.12 | 0.40 | 2.8 (2.7, 3.0) |

| Raynaud’s syndrome | 1.12 | 0.27 | 4.2 (4.0, 4.4) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 0.87 | 0.42 | 2.1 (2.0, 2.2) |

| Chronic urticaria | 0.71 | 0.55 | 1.3 (1.2, 1.4) |

| Pernicious anemia | 0.61 | 0.52 | 1.2 (1.1, 1.2) |

| Hashimoto’s thyroiditis/autoimmune thyroid disease | 0.61 | 0.43 | 1.4 (1.4, 1.5) |

| Vasculitis | 0.58 | 0.09 | 6.7 (6.3, 7.3) |

| Autoimmune disease NEC | 0.58 | 0.09 | 6.6 (6.1, 7.1) |

| Uveitis | 0.52 | 0.15 | 3.5 (3.3, 3.7) |

| Systemic sclerosis/scleroderma | 0.52 | 0.09 | 5.7 (5.2, 6.1) |

| Sarcoidosis | 0.52 | 0.27 | 1.9 (1.8, 2.1) |

| Scleritis/episcleritis | 0.45 | 0.12 | 3.9 (3.6, 4.2) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.9 (0.9, 1.0) |

| Polymyositis | 0.33 | 0.05 | 7.0 (6.3, 7.7) |

| Graves’ disease | 0.29 | 0.25 | 1.1 (1.1, 1.2) |

| Addison’s disease | 0.27 | 0.15 | 1.8 (1.6, 1.9) |

| Dermatomyositis | 0.23 | 0.04 | 6.3 (5.6, 7.1) |

| Celiac disease | 0.23 | 0.14 | 1.7 (1.6, 1.9) |

| Giant cell arteritis | 0.22 | 0.07 | 3.0 (2.8, 3.4) |

| Thrombocytopenic purpura/immune thrombocytopenic purpura | 0.21 | 0.13 | 1.7 (1.5, 1.8) |

| Morphea | 0.17 | 0.10 | 1.6 (1.5, 1.8) |

| Erythema nodosum | 0.11 | 0.03 | 4.1 (3.6, 4.8) |

| Alopecia areata | 0.10 | 0.10 | 1.1 (0.9, 1.2) |

| Hemolytic anemia | 0.10 | 0.04 | 2.2 (1.9, 2.6) |

| Chronic glomerulonephritis | 0.09 | 0.04 | 2.1 (1.8, 2.4) |

| Myasthenia gravis | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 0.09 | 0.04 | 2.2 (1.9, 2.5) |

| Vitiligo | 0.07 | 0.04 | 1.6 (1.3, 1.8) |

| Leukocytoclastic vasculitis | 0.05 | 0.01 | 6.6 (5.2, 8.5) |

As defined in the study protocol and derived from those reported in the American Autoimmune Related Disease Association’s autoimmune statistics [3]

RA rheumatoid arthritis, OA osteoarthritis, CI confidence interval, NEC not elsewhere classified

Patients with RA had elevated ORs for all autoimmune diseases, except multiple sclerosis, when compared with a matched set of patients with OA. The autoimmune diseases present at highest frequencies were ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, polymyositis, and Sjögren’s/sicca syndrome (Table 2).

Discussion

This large, retrospective, cross-sectional cohort study of US healthcare claims database data evaluated 286,601 patients with RA and 992,838 matched control patients with OA. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively screen and quantify the prevalence of other autoimmune diseases in patients with RA and OA. The findings suggest that autoimmune diseases were much more frequent in patients with RA than patients with OA. Patients with RA were four times more likely than patients with OA to have more than one autoimmune disease in addition to RA in their history. The prevalence rates of all autoimmune diseases evaluated were higher among patients with RA than those with OA. Patients with OA were more likely to have comorbid hypertension and hyperlipidemia, and patients with RA have a slight increase in occurrence of COPD. It is known that OA and cardiovascular disease have a high level of co-occurrence [25]. Similarly, COPD is not unexpected in patients with RA [26, 27]. Of the 37 autoimmune diseases evaluated here, those associated with the highest frequencies and their prevalence rates were consistent, regardless of whether diagnosis was by one (instead of two) ICD-9-CM diagnosis code.

Smaller studies evaluating the frequency of the co-existence of more than one autoimmune disease have similarly reported a greater prevalence in patients with an autoimmune disease than in controls. Having one autoimmune disease significantly increases the risk of having another [28, 29]. At present, there are few studies quantifying the occurrence of overlapping autoimmune diseases [11–20, 28, 29]. A higher prevalence of diabetes and RA in patients with psoriasis (n = 55,344) and psoriatic arthritis (n = 1952) was observed in a retrospective database study [12]. In another study, a higher prevalence of Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and inflammatory bowel disease was reported in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis [17]. Wu et al. [20] evaluated the prevalence of 21 autoimmune diseases in patients with psoriasis (n = 25,341) and found that 60% were likely to have an additional autoimmune disease compared with the general population, and psoriasis was positively associated with 14 autoimmune diseases [20]. In patients with vitiligo (n = 1098), a high prevalence (approximately 20%) of comorbid autoimmune diseases was noted [13]. Furthermore, in hospital-based cross-sectional studies (2791 and 3568 patients, respectively), approximately 3% and 4% of patients suffering from Graves’ disease and alopecia areata, respectively, were also found to have RA [11, 14].

A limited number of studies have quantified the occurrence of other autoimmune diseases in patients with RA [16, 18]. Lazurova et al. [16] evaluated 80 patients with SLE or RA and reported a prevalence of autoimmune thyroid disease determined by clinical screening of 24% [16]. In a study of 23 autoimmune diseases, in which patients with autoimmune disease were evaluated by either a rheumatologist or a neurologist, polyautoimmunity was reported in 32% of patients with RA (N = 304), with 21.1% having autoimmune thyroid disease, 11.8% Sjögren’s syndrome, and 2.6% antiphospholipid syndrome [18]. Methodological differences (e.g., code or clinical evaluation diagnosis) between these two studies and the present one (approximately one-third diagnosed by a rheumatologist) may explain their increased numbers. Cooper et al. [28] examined the prevalence of co-occurrence in a review publication and noted a positive association with inflammatory bowel disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and, in similarity with the current study, a lack of an association with multiple sclerosis in patients with RA. Somers et al. [29] conducted population-based cohort studies that included 22,888 patients with RA and demonstrated co-existence of RA, autoimmune thyroiditis, and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus at higher than expected rates, but reduced comorbidity between RA and multiple sclerosis (all of which share cytokine profiles indicative of T-helper 1-cell predominance).

The genetic basis of autoimmune diseases, including involvement of common genes, may explain the clustering of certain autoimmune diseases. Hemminki et al. [30] suggest extensive genetic sharing between RA and other autoimmune diseases. Recently, Farh et al. [8] used high-density genotyping and epigenomic data to fine map causal autoimmune disease variants from 21 autoimmune diseases that linked causal disease variants to context-specific immune enhancers and inferred a nuanced complexity to variant function.

As with any database study, limitations occur in identification of medical events or baseline comorbidities which are restricted to computerized population-based data captured as part of the medical record or claims and constrained to diagnostic code and algorithm information. Where possible, both potential intrinsic and extrinsic confounding variables were controlled in the present analysis through the study design and statistical techniques employed [14, 19]. However, these methods cannot eliminate residual confounding from unmeasured factors; data on other explanatory causes of events and the clinical path/course may not be complete or known. Autoimmune diseases are characterized by heterogeneous clinical presentations, and sometimes complex definitions and multiple ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes. Although the prevalence was noted as being higher in patients with RA than OA, potential differences in the severity of the autoimmune disorders were not evaluable on the basis of the information captured in the database evaluated in this study.

This population-based study utilized a large database (allowing potential effects to be detected) and evaluated a substantial number of autoimmune diseases (approximately half known). The use of two diagnosis codes during the baseline/follow-up period in this study improved the robustness of the data, particularly as the physician may record only one code and not all relevant codes. The use of ORs of greater than 5 should reduce the risk of a small increase being statistically significant in such large numbers of patients. However, the presence of multiple autoimmune diseases in patients with RA may not only reflect polyautoimmunity but may also be due to misclassification bias for differing reasons, e.g., as a consequence of disease complexity leading to diagnostic error, known complications associated with RA (such as patients with scleritis/episcleritis, Felty’s syndrome [RA, splenomegaly, and neutropenia], rheumatoid lung disease, rheumatoid vasculitis, and inflammatory myositis as well as presentations of extra-articular symptoms), or drug-induced symptom occurrence.

Involvement of the musculoskeletal system other than joints and of organs not considered part of the musculoskeletal system (e.g., skin, eye, and lung) occurs in about 40% of patients with RA over a lifetime of disease [31]. Misclassification could also occur as a consequence of a subsequent presentation of extra-articular features, e.g., psoriasis leading to a potential re-diagnosis to psoriatic arthritis (diagnostic error). Further misclassification could occur as a consequence of the complexity of RA, e.g., a misclassified diagnosis as RA that actually was primary Sjögren’s syndrome. The most prevalent autoimmune diseases noted in this study for patients with RA, SLE and psoriatic arthritis, have also been noted to arise or be exacerbated as a result of TNF-α blocking treatment for RA [10]. Although patients with OA and RA may have a similar number of healthcare encounters, their primary providers may be different (e.g., general practitioner versus rheumatologist), which may induce a further misclassification bias.

Conclusions

Estimates of prevalence and incidence increase understanding of a disease’s clinical, public health, and economic impact. These findings and those of previous studies suggest that evaluating and screening patients with RA for the presence of other autoimmune diseases is warranted.

As with studies in other autoimmune diseases, these data from a uniquely comprehensive screen to quantify the prevalence of other autoimmune diseases in patients with RA and OA suggest that an interrelationship between autoimmune diseases exists in patients with RA. Management and treatment options for patients with RA should be considered in line with any other comorbid autoimmune diseases present, in particular as their presence can lead to increases in disease severity, disability, and mortality [5, 9]. Understanding the occurrence of multiple autoimmune diseases may play an important role in patient management, their treatment decisions, and outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Bristol-Myers Squibb funded the publication charges and open access fees. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. The authors thank SG Nadler of Bristol-Myers Squibb for providing the pathophysiology details for the pre-specified autoimmune diseases. All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. Professional medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Fiona Boswell, PhD, and Stacey Reeber, PhD, at Caudex and was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Disclosures

TA Simon is a shareholder and employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb. H Kawabata is a shareholder and a retired employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb. S Suissa is a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, and Roche. JM Esdaile is a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb. N Ray and A Baheti have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article/as supplementary information files.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Bristol-Myers Squibb was former employment for H. Kawabata.

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/94CCF0605C64B3A1.

References

- 1.Eaton WW, Rose NR, Kalaydjian A, et al. Epidemiology of autoimmune diseases in Denmark. J Autoimmun. 2007;29:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobson DL, Gange SJ, Rose NR, et al. Epidemiology and estimated population burden of selected autoimmune diseases in the United States. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;84:223–243. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Autoimmune Related Disease Association. Autoimmune statistics. 2016. https://www.aarda.org/news-information/statistics/. Accessed 07 July 2016.

- 4.National Institutes of Health. Progress in autoimmune diseases research. 2016. http://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/autoimmune/Documents/adccfinal.pdf. Accessed 07 July 2016.

- 5.Walsh SJ, Rau LM. Autoimmune diseases: a leading cause of death among young and middle-aged women in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1463–1466. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.9.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services Office on Women's Health. Autoimmune diseases fact sheet. 2016. http://www.womenshealth.gov/publications/our-publications/fact-sheet/autoimmune-diseases.html#d. Accessed 07 July 2016.

- 7.Cho JH, Feldman M. Heterogeneity of autoimmune diseases: pathophysiologic insights from genetics and implications for new therapies. Nat Med. 2015;21:730–738. doi: 10.1038/nm.3897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farh KK, Marson A, Zhu J, et al. Genetic and epigenetic fine mapping of causal autoimmune disease variants. Nature. 2015;518:337–343. doi: 10.1038/nature13835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabriel SE, Michaud K. Epidemiological studies in incidence, prevalence, mortality, and comorbidity of the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:229. doi: 10.1186/ar2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flendrie M, Vissers WH, Creemers MC, et al. Dermatological conditions during TNF-alpha-blocking therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R666–R676. doi: 10.1186/ar1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boelaert K, Newby PR, Simmonds MJ, et al. Prevalence and relative risk of other autoimmune diseases in subjects with autoimmune thyroid disease. Am J Med. 2010;123:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edson-Heredia E, Zhu B, Lefevre C, et al. Prevalence and incidence rates of cardiovascular, autoimmune, and other diseases in patients with psoriatic or psoriatic arthritis: a retrospective study using Clinical Practice Research Datalink. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:955–963. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gill L, Zarbo A, Isedeh P, et al. Comorbid autoimmune diseases in patients with vitiligo: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang KP, Mullangi S, Guo Y, et al. Autoimmune, atopic, and mental health comorbid conditions associated with alopecia areata in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:789–794. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang JH, Chen YH, Lin HC. Comorbidities amongst patients with multiple sclerosis: a population-based controlled study. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:1215–1219. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazurova I, Benhatchi K, Rovensky J, et al. Autoimmune thyroid disease and autoimmune rheumatic disorders: a two-sided analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:211–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makredes M, Robinson D, Jr, Bala M, et al. The burden of autoimmune disease: a comparison of prevalence ratios in patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rojas-Villarraga A, Amaya-Amaya J, Rodriguez-Rodriguez A, et al. Introducing polyautoimmunity: secondary autoimmune diseases no longer exist. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:254319. doi: 10.1155/2012/254319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheth VM, Guo Y, Qureshi AA. Comorbidities associated with vitiligo: a ten-year retrospective study. Dermatology. 2013;227:311–315. doi: 10.1159/000354607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon KY, et al. The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:924–930. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Overhage JM, Ryan PB, Reich CG, et al. Validation of a common data model for active safety surveillance research. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19:54–60. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology. Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPP). 2016. http://pharmacoepi.org/resources/guidelines_08027.cfm. Accessed 07 July 2016.

- 23.MacLean CH, Park GS, Traina SB, et al. Positive predictive value (PPV) of an administrative data-based algorithm for the identification of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:S106. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernandes GS, Valdes AM. Cardiovascular disease and osteoarthritis: common pathways and patient outcomes. Eur J Clin Invest. 2015;45:405–414. doi: 10.1111/eci.12413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugiyama D, Nishimura K, Tamaki K, et al. Impact of smoking as a risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:70–81. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.096487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nannini C, Medina-Velasquez YF, Achenbach SJ, et al. Incidence and mortality of obstructive lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:1243–1250. doi: 10.1002/acr.21986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper GS, Bynum ML, Somers EC. Recent insights in the epidemiology of autoimmune diseases: improved prevalence estimates and understanding of clustering of diseases. J Autoimmun. 2009;33:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Somers EC, Thomas SL, Smeeth L, et al. Are individuals with an autoimmune disease at higher risk of a second autoimmune disorder? Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:749–755. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hemminki K, Li X, Sundquist J, et al. Familial associations of rheumatoid arthritis with autoimmune diseases and related conditions. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:661–668. doi: 10.1002/art.24328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Turesson C, et al. Incidence of extraarticular rheumatoid arthritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, in 1995–2007 versus 1985–1994: a population-based study. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:983–989. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.101133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article/as supplementary information files.