Abstract

Wnt/β-catenin signaling is required for embryonic dermal fibroblast cell fate, and dysregulation of this pathway is sufficient to promote fibrosis in adult tissue. The downstream modulators of Wnt/β-catenin signaling required for controlling cell fate and dermal fibrosis remain poorly understood. The discovery of regulatory long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and their pivotal roles as key modulators of gene expression downstream of signaling cascades in various contexts prompted us to investigate their roles in Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Here, we have identified lncRNAs and protein-coding RNAs that are induced by β-catenin activity in mouse dermal fibroblasts using next generation RNA-sequencing. The differentially expressed protein-coding mRNAs are enriched for extracellular matrix proteins, glycoproteins, and cell adhesion, and many are also dysregulated in human fibrotic tissues. We identified 111 lncRNAs that are differentially expressed in response to activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. To further characterize the role of mouse lncRNAs in this pathway, we validated two novel Wnt signaling- Induced Non-Coding RNA (Wincr) transcripts referred to as Wincr1 and Wincr2. These two lncRNAs are highly expressed in mouse embryonic skin and perinatal dermal fibroblasts. Furthermore, we found that Wincr1 expression levels in perinatal dermal fibroblasts affects the expression of key markers of fibrosis (e.g., Col1a1 and Mmp10), enhances collagen contraction, and attenuates collective cell migration. Our results show that β-catenin signaling-responsive lncRNAs may modulate dermal fibroblast behavior and collagen accumulation in dermal fibrosis, providing new mechanistic insights and nodes for therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: gene expression, Mmp10, Wincr1, Wincr2, dermis, development

Introduction

Wnt/β-catenin signaling has a diverse role in both embryonic mouse skin development and in human skin diseases such as pilomatricomas, dermal hypoplasia, and fibrosis (Wang et al., 2007; Lam and Gottardi, 2011; Hamburg and Atit, 2012; Lim and Nusse, 2012). β-catenin is a key transducer of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and a regulator of transcription (van Amerongen and Nusse, 2009; Schuijers et al., 2014; McCrea and Gottardi, 2016). Cell type and context-specific target gene expression provide specificity for the diverse functions of the Wnt signaling pathway (Nakamura et al., 2009; Nusse and Clevers, 2017). Elucidating the downstream modulators of the Wnt signaling pathway is critical to our understanding of how this pathway influences distinct cell types in development and disease.

Dermal fibroblasts are key contributors to hair follicle development, regional identity, skin patterning, wound healing, and skin fibrosis (Chang et al., 2002; Eames and Schneider, 2005; Rendl et al., 2005; Enzo et al., 2015). We have previously demonstrated that dermal Wnt/β-catenin activity is required for mouse embryonic dermal fibroblast identity and hair follicle initiation (Atit et al., 2006; Ohtola et al., 2008; Tran et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012). Activation of the Wnt signaling pathway in humans is also a common feature in fibrosis of varying organs such as lung, liver, kidney, and skin (Enzo et al., 2015). We found that sustained Wnt/β-catenin activation in dermal fibroblasts is sufficient to cause dermal fibrosis in the adult mouse (Akhmetshina et al., 2012; Hamburg and Atit, 2012; Mastrogiannaki et al., 2016). Transcriptome analysis of mouse fibrotic dermis showed an increase in mRNA levels of regulatory genes, such as Col7a1, Ccn3/Nov, Biglycan, and Matrix Metalloproteinase 16 (Mmp16), a subset of which are also up-regulated in human skin fibrosis and tumor stroma (Hamburg-Shields et al., 2015). Thus, studying the various mechanisms of β-catenin-mediated gene regulation will provide new insights into how context-specific transcriptional targets are activated and repressed in skin development and disease.

In recent years, lncRNAs have emerged as crucial intermediate facilitators for a variety of cellular pathways and gene expression networks (Rinn and Chang, 2012; Wan and Wang, 2014). Regulatory lncRNAs are defined as >200 nt-long RNA molecules readily present within both the cytosol and nucleus but lacking protein-coding capacity. Various studies have implicated lncRNAs in directly facilitating gene expression, both in cis and in trans (Khalil et al., 2009; Moran et al., 2012). Furthermore, studies have documented the existence of differentially expressed lncRNAs within specific fibrotic conditions (Huang et al., 2015; Micheletti et al., 2017; Piccoli et al., 2017; Qu et al., 2017). Recently, TGFβ-responsive lncRNAs have been shown to directly control the expression of fibrotic genes, demonstrating a role for lncRNAs in a pathway with a similar function as Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Fu et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016). An increasing number of studies are investigating the direct role that lncRNAs play in influencing Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Fan et al., 2014; Vassallo et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2016).

Wnt/β-catenin signaling-induced lncRNAs that function as downstream effectors of Wnt signaling to modulate gene expression have yet to be fully characterized. Here, we expressed a stabilized version of β-catenin protein from the endogenous locus in neonatal mouse primary dermal fibroblasts to identify Wnt/β-catenin signaling-responsive mRNAs and lncRNAs. We functionally characterized one of the most differentially expressed lncRNAs, GM12603, referred to as Wincr1 in the context of fibrotic gene expression and fibroblast behavior. Our results show that Wincr1 has gene-regulatory and functional roles in key behaviors of dermal fibroblasts such as collective cell migration and collagen contraction.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Ethics

Ctnnb1Δex3/+ (Harada et al., 1999), Engrailed1Cre (En1Cre) (Kimmel et al., 2000), Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(rtTA,EGFP)Nagy (R26rtTA) Jax labs stock: 005670 (Belteki et al., 2005), Teto-deltaN89 β-catenin (Mukherjee et al., 2010) were maintained on mixed genetic background (CD1, C57Bl6) and genotyped as previously described. Triple transgenic Engrailed1Cre/+; Rosa26rtTA/+; Teto-deltaN89 β-catenin/+ experimental mice were generated. For each experiment, a minimum of three mutants with litter-matched controls were studied except where otherwise noted. Animals of both sexes were randomly assigned to all studies. Case Western Reserve Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal procedures in accordance with AVMA guidelines (Protocol 2013-0156, approved 21 November 2014, Animal Welfare Assurance No. A3145-01).

Collection and Culture of Primary Dermal Fibroblasts

Whole ventral skin from Ctnnb1Δex3/+ mice was dissected from the trunk of postnatal days 4–7 (P4-7) mice and minced (Harada et al., 1999). Skin was incubated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12) (Thermo Fisher Cat. No. 11320) and 50 mg/mL Liberase DL (Roche Cat. No. 5401160001) at 37°C under constant rotation for 1 h. Dermis was dissociated by vigorous pipetting and passing through an 18 gauge needle (BD Cat. No. 305196). Cells from each animal were cultured individually in complete growth media (DMEM (Thermo Fisher Cat. No. 11995065) + 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Cat. No. 10082147) + 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Invitrogen Cat. No. 15140122) + 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic) (Invitrogen Cat. No. 14240062) in 5% CO2 except where otherwise noted. After 90 min, media was removed and replaced with fresh culture media. After two passages, Adenovirus was administered in basal DMEM (no FBS). Dermal fibroblasts were infected with Adenovirus-Cre (366-500 MOI) or Adenovirus-GFP (366 MOI) (Adenovirus purchased from University of Iowa). After 48 h, recombination of Ctnnb1 Exon 3 was confirmed with site specific PCR under standard conditions. Primers Neo PMR (5′ AGACTGCCTTGGGAAAAGCG 3′) and Cat-AS5 (5′ ACGTGTGGCAAGTTCCGCGTCATCC 3′) were used to identify the targeted allele with a ∼500 bp amplicon and GF2 (5′GGTAGGTGAAGCTCAGCGCAGAGC 3′) and Cat-AS5 identified the recombined allele with an expected amplicon of ∼700 bp (Harada et al., 1999).

For in vivo induction of stabilized β-catenin expression in Engrailed1Cre/+; Rosa26rtTA/+; Teto-deltaN89β-catenin/+ mice, pregnant dams were given 80 μg of doxycycline (Sigma Cat. No. D9891) per gram of body weight by intraperitoneal injection at embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5) and embryonic cranial and dorsal dermal skin were harvested at E13.5. In vitro stabilized β-catenin expression was induced by treating Engrailed1Cre/+; Rosa26rtTA/+; Teto-deltaN89β-catenin/+ P4 ventral dermal fibroblasts cells with 2 μg/mL doxycycline in complete growth media for 4 days. For induction-reversal experiments, duplicate cultures were then switched to complete growth media without doxycycline for 48 h prior to RNA isolation.

Whole-Genome RNA Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from embryonic tissues in vivo and dermal fibroblasts in vitro using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Cat. No. 15596026). RNA was isolated using the RNeasy MinElute kit (Qiagen Cat. No. 74204) with DNAse1 (Qiagen Cat. No. 79254) treatment, following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration and quality were measured using the NanoDrop 8000 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer.

Libraries were prepared by the CWRU Genomics Sequencing Core, using the True-Seq Stranded Kit (Illumina). Paired-end sequencing was carried out on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform. Resulting 100 bp reads were mapped to the mm10 mouse genome release using TopHat and Cufflinks. Mapped raw reads were counted, normalized to total mapped reads, and used for differential gene expression (Cuffdiff and Seqmonk standard settings). Differential expression was defined as an absolute fold change greater than 2, and Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted P-value less than 0.05. Normalized mapped reads are available on Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE103870) using the private token from the editor.

Quantitative PCR and Primers

Total RNA was extracted from P4 ventral dermal fibroblasts between passage 3–6 as mentioned above. cDNA was generated using the Invitrogen High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Cat. No. 4374966). Relative mRNA quantities of select genes were determined using the Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies Cat. No. 4376600) and the ΔCt or ΔΔCt method where applicable (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001; Schmittgen and Livak, 2008). In all plots, sample and control RQs were normalized to the mean RQ of the control group. Axin2 quantity was measured relative to the reference gene ActB using Taqman probes from Thermo Fisher (Mm00443610_m1 and Mm02619580_g1, respectively) or HPRT (mm1545399_m1). Wincr1 isoform1 (F: TGATCCCACTGAAAATGCTG, R:GGTGATTTGACCTGCCATCT) and Wincr2 (F:GGCCTGGATAGAGGTCTCC, R:TAGTTCTCTCCATCGGTTTCC) quantities were measured relative to reference gene RPL32 (F:TTAAGCGAAACTGGCGGAAAC, R:TTGTTGCTCCCATAACCGATG) using custom-designed primers (Invitrogen) and SyBr Green reagents(Invitrogen Cat. No. 4367659). Mmp10 and Col1a1 quantities (Mm01168399_m1 and Mm00801666_g1, respectively) were measured relative to reference gene ActB expression, using TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Cat. No. 4369016). Non-coding gene primers were designed using Primer3Plus1. Primer sequences for RPL32 and Mmp10 were acquired through the MGH Primer Bank Site2. Primer sequences for Col1a1 were identified previously (He et al., 2005).

Statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism 7. For experiments in which cells from the same animal were used in control and experimental conditions, a paired t-test was used. In all other instances, an unpaired t-test was used. Significance for all purposes was defined as ∗P-value ≤ 0.05, ∗∗P-value ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗P-value ≤ 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P-value ≤ 0.0001. Paired samples are shown as dots connected by a line where applicable. Expression across different tissues are shown as mRNA levels relative to reference gene (2-ΔCt). In all other plots, individual relative quantities (2-ΔΔCt) are shown along with mean and standard error of the mean.

Bioinformatic Analysis

Heatmaps were generated using all mRNA or lncRNA genes considered significantly differentially expressed [abs(fold change) > 2, adjusted P-value < 0.05] between GOF and control samples. Color was assigned to each sample on a basis of Z-score of fragments per kilobase mapped (FPKM) compared to other samples’ FPKM of the same gene (row Z-score). Heatmaps were clustered hierarchically based on the aggregate differential gene expression profiles using the DESeq2 package in R.

DAVID Functional Annotation Clustering3 was performed on all differentially expressed protein-coding genes [abs(fold change) > 2, adjusted P-value < 0.05]. Gene lists were entered as Gene Symbols. All settings were default. The top five ranked clusters are shown, with clusters enriched among up-regulated genes shown as positive and clusters enriched among down-regulated genes shown as negative.

Overrepresentation of predicted transcription factor binding sites was determined using oPOSSUM 3.0 Single Site Analysis (SSA)4 (Ho Sui et al., 2007; Kwon et al., 2012). Gene lists were loaded into the browser-based software by gene symbol, and putative transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) were scored based on their overrepresentation in the areas surrounding the transcription start site (TSS) of such genes, as compared to prevalence in the rest of the genome. All 29,347 genes in the oPOSSUM database were used as background. For analysis of TFBS enrichment around lncRNAs, custom FASTA files were generated for the promoter sequence of each gene. Proximity to TSS was defined as ±5 kb for all analysis. All JASPAR PBM profiles were queried. Each TFBS was assigned a Z-score and a Fisher score for overrepresentation. TFBS were then plotted according to these scores using GraphPad Prism 7. Thresholds were determined as follows: Z-score - Mean + (2 × Standard Deviation), Fisher score -Mean + Standard Deviation as previously described (Kwon et al., 2012).

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was used to identify known gene expression signatures similar to the differential expression of genes in GOF dermal fibroblasts (Mootha et al., 2003; Subramanian et al., 2005). GSEA was run as a Java Applet. MSigDB C2 Curated Gene Sets were queried. Gene sets smaller than 15 genes and larger than 500 genes were excluded from the analysis and 1000 gene_set permutations were used. All other settings remained default.

The human matrisome gene list was accessed through the MIT Matrisome Project at MatrisomeDB5. The intersection of this list with others was performed in Microsoft Excel.

Coexpression networks were constructed using Cytoscape version 3.4.0 (Shannon et al., 2003). Candidate genes were selected on the basis of significant differential upregulation (adjusted P-value < 0.05 and fold change > 2) and inclusion in the Matrisome gene list (see above). An FPKM table was constructed in Microsoft Excel consisting of these candidate genes as well as Axin2, Wincr1, and Wincr2. This table was loaded into Cytoscape as an unassigned table. The plugin “Expression Correlation” was used (with a Low Cutoff of -1 and a High Cutoff of 0.6) to generate a correlation network. The built-in tool “Network Analyzer” was used to further analyze the network for node degree. A custom style was created to visualize the network, in which edge color correlates with strength of correlation (red:high CC). Node size correlated with number of first neighbors (degree).

Human Fibrotic Disease Study Expression Analysis

Microarray data from nine human studies of various fibrotic conditions were analyzed using Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Data were analyzed using the GEO2R tool. Genes with average fold change > 1.5 and adjusted P-value < 0.05 were considered significantly differentially expressed.

In Vitro Lentivirus Overexpression and Gapmer Knockdown of Wincr1

Full-length isoform 1 of Wincr1 was assembled from synthetic oligonucleotides and PCR products and subcloned into pMA-T (Life Technologies, Ref. No. 1725930). Wincr1 lentivirus was generated by subcloning Wincr1 from pMA-T into the Nco1-EcoRV region of pENTR4 (Thermo Fisher Cat. No. A10465) vector and then swapping it into the pGK destination vector (Addgene Cat. No. 19068). Lentivirus was generated in 293T (f-variant) cells (ATCC Cat. No. 3216) by simultaneously transfecting pGK Destination Vector containing Wincr1 (4.5 μg), PMD2G helper plasmid (1.6 μg) (Addgene Cat. No. 12259), and pCMV-dR874 plasmid (3.2 μg), using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (18 μL) (Invitrogen Cat. No. L30000015) in 1.5 mL Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Cat. No. 31985062) media in a 6 cm dish. Cells were selected in Puromycin (2 μg/mL) (Sigma Cat. No. P8833). Virus was collected from 293T conditioned cell media at 24 and 52 h after transfection, clarified with 45 μm pore filter (PES membrane, Thermo Fisher Cat. No. 7252545) and frozen. Lentivirus conditioned media was titered on 293T cells at 3.25–50% dilutions. After 3 days, infected cells were selected by treatment with Puromycin (2 μg/mL) for 3 days. Stable expressing P4 mouse ventral dermal fibroblast cells lines were propagated for further experiments. Wincr1 overexpression was confirmed by qRT-PCR as described.

Wincr1 knockdown was achieved with custom LNA-GapmeRs designed and synthesized by Exiqon6. Sequences targeting Wincr1 (GACTAGGATGATAGAT) and a negative (scrambled) control (AACACGTCTATACGC) were acquired. LNA GapmeRs were reconstituted to 50 μM in tissue culture-grade water as per manufacturer’s instruction. Transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent in Opti-MEM. Dermal fibroblasts were seeded in a 12-well cell culture treated plate and transfected in 500 μL of Opti-MEM containing 2 μL Lipofectamine 3000 and a final LNA GapmeR concentration of 50 nM. Active transfection was carried out for 6 h, at which time the Lipofectamine 3000 containing media was replaced with complete growth media. Additional LNA GapmeRs were added for a final concentration of 100 nM. After 48 h of unassisted transfection, cells were harvested and RNA was extracted and analyzed for gene expression changes as described above. The knockdown of Wincr1 expression was confirmed by qRT-PCR.

Proliferation, Migration, and Contraction Functional Assays

To measure cell proliferation, a standard growth curve assay was performed on P4 ventral dermal fibroblasts between passage 4–6 as described above. 30,000 cells were plated in duplicate into a 12 well plate, with cell number being assessed using Trypan blue (Invitrogen/Gibco Cat. No. 1520061) exclusion on the Cell Countess (Invitrogen Cat. No. C10281). Collective cell migration was assessed using a qualitative scratch assay (Liang et al., 2007). Briefly, a 200 μL pipet tip was used to scratch the monolayer and create a 400 μm gap. Images of cells were taken at time (T) 0, 15, and 22 h. Images were taken on Leica S6D microscope with MC120 HD camera with Leica software. Cell contraction was assessed using the Cell Contraction Assay Kit (Cell Biolabs Inc., CBA-201), following manufacturer instruction. Images of cells were taken with Olympus IX71 microscope with Olympus BX60 camera using Olympus DP controller software. All images were analyzed in Image J software (Schneider et al., 2012).

Results

Global RNA Expression Is Altered after β-catenin Stabilization in Dermal Fibroblasts

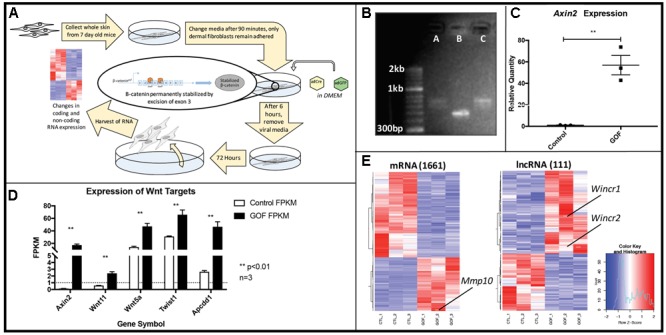

To identify coding and non-coding RNAs downstream of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, we infected neonatal dermal fibroblasts carrying Ctnnb1Δex3/+ with Adenovirus Cre (Ad-Cre) (Figure 1A). Recombination of Exon 3 of Ctnnb1 produces a stabilized form of β-catenin protein, referred to as Gain of Function (GOF), which lacks the phosphorylation site for degradation and constitutively activates the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Using site-specific primers, we confirm the consistent and effective Ad-Cre-mediated excision of Ctnnb1 Exon 3 by 48 h post-infection, compared to fibroblasts carrying the same transgene and transduced with Adenovirus GFP (Figure 1B) (Harada et al., 1999). Axin2, a well-established direct target of β-catenin (Jho et al., 2002), was up-regulated by 40 to 70-fold in cells at 72 h post-infection across all GOF samples (Figure 1C) further demonstrating successful excision of Ctnnb1 Exon 3 and activation of the pathway.

FIGURE 1.

In vitro genetic recombination of β-catenin (Ctnnb1Δex3) in dermal fibroblasts results in a strong Wnt signaling expression signature as well as global expression changes in coding and non-coding genes. (A) Schematic of the workflow (B) Ctnnb1Δex3 recombination by Adenovirus-Cre (AdCre) infection was confirmed by Ctnnb1 exon3 site-specific PCR in lanes A and C, compared to the control lane B, infected with Adenovirus-GFP. (C) Relative mRNA quantity of Axin2, a direct β-catenin target is significantly higher in β-catenin stabilized gain of function dermal fibroblasts (GOF) (P-value = 0.0035, n = 3). (D) Known β-catenin targets are higher in GOF dermal fibroblasts by RNAseq (n = 3). (E) Heat map showing hierarchical clustering (based on entities and samples) of all differentially expressed mRNAs (1661) and lncRNAs (111) (P-value < 0.05, fold change > 2) in response to β-catenin stabilization.

Next, we isolated total RNA and performed expression profiling on control and GOF neonatal dermal fibroblasts (n = 3) by whole-genome RNA-sequencing at 72 h post Ad-Cre infection (deposited in GEO, GSE103870). We quantified gene expression using FPKM (see Materials and Methods) and further verified GOF status by examining FPKM values of several well-known Wnt/β-catenin signaling targets in dermal fibroblasts in vivo, such as Wnt5a, Wnt11, Apcdd1, and Twist2 (Budnick et al., 2016). All target gene expression levels were significantly higher across all three GOF samples, serving as quality control for the sample preparation and sequencing (Figure 1D). Within expressed mRNAs and lncRNAs (FPKM > 1), GOF samples independently clustered together via Pearson correlation against the controls (Supplementary Figure S1). In total, we identified 1,661 mRNAs and 111 lncRNAs that were differentially expressed across all GOF samples (fold change > 2, adjusted P-value < 0.05) (Figure 1E). These findings demonstrate that Wnt signaling differentially regulates lncRNAs as well as mRNAs in dermal fibroblasts.

Stabilization of β-catenin Leads to Dysregulation of Matrisome Genes Relevant to Human Fibrosis

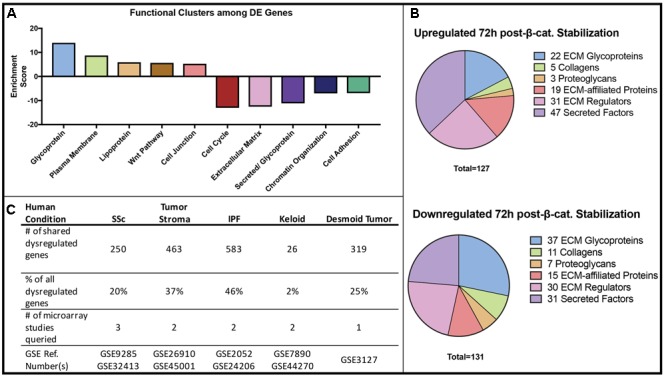

We performed Gene Ontology (GO) Analysis for all differentially expressed mRNAs. These analyses identified key functional groups affected by Wnt/β-catenin signaling in dermal fibroblasts. Through DAVID, the differentially expressed mRNAs were grouped by functional clusters, with positive enrichment scores indicating functional clusters comprised of up-regulated genes and negative scores indicating clusters of down-regulated genes (Figure 2A). The highest scoring functional clusters enriched in up-regulated genes included Glycoprotein, Membrane, Cell junction, and Wnt signaling (fold change > 2, adjusted P-value < 0.05). Functions including Extracellular Matrix and Secreted/Glycoprotein were also highly enriched among those genes that were down-regulated in GOF dermal fibroblasts (fold change, <0.5-adjusted P-value < 0.05).

FIGURE 2.

Gene Ontology and disease comparison analysis of all β-catenin responsive genes. (A) The functional annotation (DAVID) of differentially expressed (DE) genes in β-catenin stabilized GOF. (B) A defined matrisome gene dataset (Naba et al., 2012) overlapped with differentially expressed genes in GOF yielded 127 up-regulated and 131 down-regulated matrisome genes consisting of ECM glycoproteins, secreted factors and ECM-regulators. (C) Differentially expressed genes in GOF dataset are also dysregulated in a variety of human fibrotic conditions.

Since DAVID functional clustering analysis highlighted a strong overrepresentation of ECM genes, we used an existing gene set consisting of matrix encoding and related genes or “matrisome” (Naba et al., 2012), to further annotate the categories of ECM-associated genes. We identified 127 significantly up-regulated and 131 significantly down-regulated matrisome genes in GOF samples compared to controls. Of all significantly dysregulated genes in GOF samples, 9.1% were included in the matrisome gene list. Both up-regulated and down-regulated gene sets revealed expression changes in ECM Glycoproteins, Secreted factors, and ECM-regulators (Figure 2B). Of the 258 differentially expressed matrisome genes, 59 were annotated as ECM glycoproteins, 16 are Collagen proteins, 10 are Proteoglycans and 34 are ECM affiliated genes, while the rest serve ECM regulatory functions. Within the various functions of differentially expressed genes, the ECM-encoding and matrisome-related genes are of note due to their function in fibrogenesis.

We utilized Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) to identify biological signatures enriched in GOF samples (Subramanian et al., 2005). We input 3114 mouse genes (adjusted P-value < 0.05) expressed in our control and GOF fibroblasts, 2371 of which corresponded to human genes with microarray identifiers in the GSEA database (Supplementary Figure S3A). The top four gene sets enriched in GOF samples were targets of Suz12, EED, and exhibited histone modification of H3K4Me2/H3K27Me3. They are all related to the function of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), a well-characterized epigenetic mechanism of gene repression (Supplementary Figures S3B–F). A recent study found functional links between lncRNAs, Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and components of PRC2 in liver cancer stem cells (Zhu et al., 2016). The ontology analysis suggests that epigenetic mechanisms may serve as intermediate modulators of Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Finally, we compared the list of differentially expressed genes in our GOF mouse dermal fibroblast dataset to genes differentially expressed in human biopsied fibrotic tissue such as systemic sclerosis (SSc), desmoid tumors, idiopathic lung fibrosis, and tumor stroma (Hamburg-Shields et al., 2015). Of the genes differentially expressed in GOF mouse dermal fibroblasts compared to controls, we found varying percentages to also be dysregulated in human fibrotic conditions (Figure 2C). Our analysis shows that the expression changes in GOF dermal fibroblasts in vitro after 48 h of stabilization of β-catenin is consistent with findings from profiling in vivo fibrotic mouse dermis in that Wnt/β-catenin signaling may regulate the expression of matrisome genes and contribute to fibrotic conditions (Hamburg-Shields et al., 2015). Therefore, we demonstrate that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling-responsive genes in dermal fibroblasts are also dysregulated in at least one type of human fibrotic tissue.

LncRNAs Wincr1 and Wincr2 Positively Respond to β-catenin Activity in a Tissue-Specific Manner

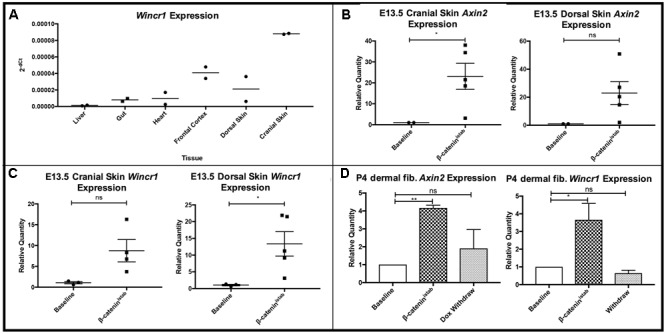

We next focused on the 111 differentially expressed lncRNAs in the GOF samples as compared to controls. Two top novel candidate Wnt Induced Non-Coding RNAs (Wincr1 and Wincr2) were highly differentially expressed (Figure 3A). Wincr1 isoform 1(ENSMUST00000146678.1) (GM12603) was expressed at 37 FPKM in control samples and at 551 FPKM in the GOF samples (average 14x fold-change). Wincr2 (GM12606) was expressed at 3.24 FPKM in control samples and 28.27 FPKM in GOF samples, marking over an 8x fold change between conditions. Therefore, we validated increase of Wincr1 with isoform 1 specific PCR primers and Wincr2 expression by qRT-PCR in four independent biological replicates of both GOF and controls in P4 ventral dermal fibroblasts in vitro (Figures 3B,C).

FIGURE 3.

β-catenin stabilized GOF have increased expression of Wincr1 and Wincr2. (A) Heatmap representative of RNA-Seq FPKM values of two candidate lncRNAs, Wincr1 and Wincr2 from control and GOF dermal fibroblasts (n = 3). (B,C) Differential expression of lncRNA targets analyzed by qRT-PCR. LncRNA expression levels are significantly up-regulated within in vitro β-catenin stabilized GOF fibroblasts vs. the control (Wincr1: n = 4, Wincr2: n = 6). ∗∗P-value ≤ 0.01.

To investigate the tissue-specific expression profile of Wincr1 in vivo, we used embryonic skin in which we have previously shown a strong instructive role for Wnt/β-catenin signaling in dermal fibroblast identity and hair follicle initiation (Atit et al., 2006; Ohtola et al., 2008; Fu et al., 2009; Tran et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012). We assayed for Wincr1 in vivo in embryonic cranial and dorsal dermis during hair follicle initiation at E13.5 by qRT-PCR. Wincr1 displayed a clear tissue-specific expression pattern during normal development in E13.5 mouse embryos. We found Wincr1 transcript to be abundant in the cranial (head) and dorsal skin, as compared to expression in the embryonic liver, heart, and gut (n = 2) (Figure 4A). Wincr1’s enhanced presence in embryonic cranial and dorsal skin vs. other tissues suggests that our lncRNA candidate could play a role in fibroblast biology. Wincr2 followed a similar tissue-specific trend in embryonic tissues (Supplementary Figure S4A).

FIGURE 4.

Wincr1 is differentially expressed in embryonic and perinatal mesenchyme and dynamically responds to changes in β-catenin activity levels. (A) Survey of Wincr1 mRNA levels in embryonic (E13.5) tissues reveals highest expression in embryonic cranial and dorsal skin (n = 2). (B) Axin2 expression levels were used to validate β-catenin activity following doxycycline induction for 4 days in Engrailed1Cre/+; Rosa26rtTA/+; Teto-ΔN89 (β-catistab) E13.5 primary fibroblasts in vitro. (P-value = 0.0237, n = 2,5). (C) Relative quantity of Axin2 and Wincr1 mRNA in β-catistab E13.5 embryonic fibroblasts. (D) Relative quantity of Axin2 and Wincr1 mRNA in β-catistab P4 fibroblasts following doxycycline induction for 4 days and subsequent withdrawal for 2 days in vitro. ∗P-value ≤ 0.05, ∗∗P-value ≤ 0.01.

Wincr1 Dynamically Responds to Wnt/β-catenin Signaling Activity

We further tested β-catenin-responsive expression of Wincr1 with doxycycline-inducible stabilized β-catenin (β-catistab) in E13.5 Engrailed1Cre/+; Rosa26rtTA/+; Teto-deltaN89β-catenin/+ cranial and dorsal dermal fibroblasts in vitro (Mukherjee et al., 2010). Relative Axin2 mRNA expression level was measured by qRT-PCR to confirm GOF status after doxycycline administration (Figure 4B). In response to β-catistab, Wincr1 was significantly higher in embryonic dorsal and cranial dermal fibroblasts (Figure 4C). In the same in vitro GOF samples assayed for Wincr1 expression, an increase in Wincr2 expression was observed but did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Figures S4B,C).

We tested for dynamic β-catenin-responsive expression of Wincr1 in doxycycline inducible-reversible levels of β-catistab in vitro in P4 ventral dermal fibroblasts. Addition of doxycycline and subsequent withdrawal in culture media allowed us to induce and reverse expression of stabilized β-catenin as shown by Axin2 mRNA levels in Engrailed1Cre/+; Rosa26rtTA/+; Teto-deltaN89β-catenin/+ P4 dermal fibroblasts (Figure 4D). Similarly to the previous result, Wincr1 responded dynamically to the induction and reversal of β-catistab levels (Figure 4D), further establishing Wincr1 as a Wnt/β-catenin signaling-responsive lncRNA in embryonic and perinatal dermal fibroblasts obtained from cranial and trunk skin.

Wincr1 Influences Expression of Some Matrisome Genes

We next utilized co-expression network construction to identify and separate putative regulatory targets of both β-catenin and Wincr1. It has been shown that correlation of expression between two genes across samples can imply a common regulatory factor (Allocco et al., 2004). Using FPKM values from control and GOF samples, we constructed a network of up-regulated mouse matrisome genes connected on the basis of correlation coefficient (CC > 0.6). Genes were grouped into two clusters: those that correlate with Axin2 (97 genes), and those that do not correlate with Axin2 (6 genes). By excluding genes whose expression correlated with that of Axin2, a known direct target of β-catenin, we identified a small number of matrisome genes that might be indirect targets of β-catenin regulation. Relevant fibrosis-related marker genes were selected as possessing some or all of the following traits:

-

simple (a)

Up-regulated in β-catistab dermal fibroblasts by comparison of FPKM (Figure 1E)

-

simple (b)

Inclusion in the Matrisome gene set (Figure 2B)

-

simple (c)

Overexpressed in human fibrotic tissue microarray (Figure 2C)

-

simple (d)

Exclusion from the Axin2 cluster of the correlation network (Supplementary Figure S5)

Of the genes that passed all four criteria, Matrix Metalloproteinase-10 (Mmp10) was selected for functional investigation. Furthermore, there was no significant enrichment of predicted Tcf/Lef binding motifs within 5 kb of the transcriptional start site of Mmp10 and other differentially expressed mRNAs (Supplementary Figure S2).

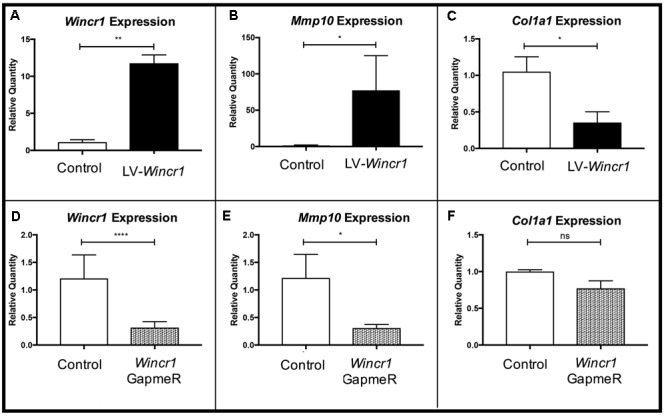

To elucidate Wincr1 function in gene regulation and dermal fibroblast biology, we either overexpressed or knocked down Wincr1 in P4 ventral dermal fibroblasts in vitro. For overexpression, we generated a lentivirus construct to overexpress Wincr1 (LV-Wincr1). For knockdowns of Wincr1, we utilized LNA GapmeRs (Wincr1 GapmeRs). We confirmed increase in Wincr1 RNA expression levels after infection of LV-Wincr1 (Figure 5A) and reduction after transient transfection with Wincr1 GapmeR (Figure 5D). Dermal fibroblasts with either over- or knocked down expression of Wincr1 and the parent control cells were then used to investigate changes in the expression of dermal identity and fibrosis-related gene candidates.

FIGURE 5.

Gene regulatory function of Wincr1. (A,D) Relative quantity of Wincr1 RNA is significantly altered as a result of lentivirus or GapmeR infection. (B,E) Relative quantity of Mmp10 mRNA levels correlate with changes in Wincr1 expression levels. (C,F) In LV-Wincr1, relative quantity of Col1a1 is significantly reduced and was comparable between control and Wincr1 GapmeR (n = 5 biological replicates). ∗P-value ≤ 0.05, ∗∗P-value ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗∗P-value ≤ 0.0001.

We found Mmp10 mRNA level was highly correlated with levels of Wincr1 in dermal fibroblasts (Figures 5A,B,E). After infection with LV-Wincr1, expression of Mmp10 increased dramatically compared to the control (Figure 5B). Conversely, knockdown of Wincr1 via GapmeRs resulted in a decrease in Mmp10 expression by ∼30% of basal levels (Figure 5E). Also, the expression of Col1a1, a key fibrotic marker, correlated negatively with overexpression of Wincr1 (Figure 5C). However, we did not observe a significant difference in Col1a1 mRNA levels upon knockdown of Wincr1 (Figure 5F). The mRNA levels of markers for fibroblasts identity Platelet derived growth factor receptor alpha (Pdgfra) and β-catenin responsive genes and fibrotic markers such as Loxl4, Col5a1, which were up-regulated in GOF, did not correlate with Wincr1 mRNA level, indicating that Wincr1 does not regulate their expression in our system (Supplementary Figure S6). Co-expression analysis also identified Has2 and Methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (Mtap), the latter of which shares a locus with Wincr1. However, the relative mRNA levels of Has2 and Mtap did not correlate with changes in Wincr1 level (Supplementary Figure S4). Thus, our findings demonstrate that Mmp10 is a key target of Wincr1.

To test if Wincr1 and β-catenin have synergistic effects on gene expression, we infected Engrailed1Cre/+; R26rTA/+; Teto-β-catenin (β-catistab) P4 ventral dermal fibroblast with LV-Wincr1. We validated induction of Axin2 in β-catistab condition and confirmed comparable overexpression of Wincr1 in lentivirus infected β-catistab condition (Supplementary Figure S7). Mmp10 and Col1a1 mRNA levels in LV-Wincr1+ β-catistab were not significantly altered from LV-Wincr1 only (Supplementary Figure S5). These results suggest that Wnt/β-catenin signaling and Wincr1 do not synergize to regulate Mmp10 and Col1a1 mRNA and likely function in a linear pathway.

Wincr1 Mitigates Migration and Enhances Collagen Gel Contraction of Dermal Fibroblasts

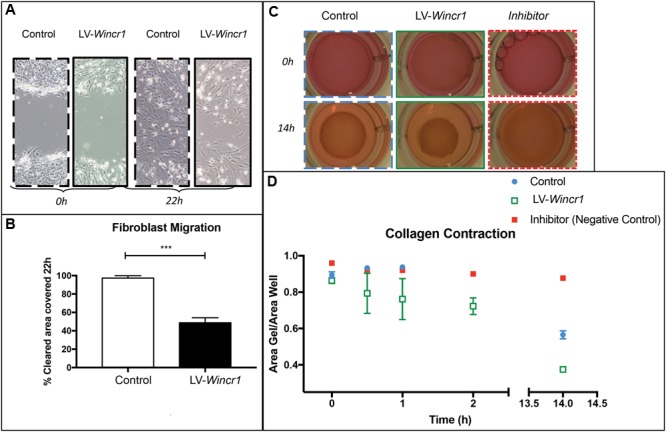

Given the gene regulatory effect of Wincr1 on Mmp10 expression, we sought to determine functional effects of Wincr1 on cellular behavior of dermal fibroblasts. In order to prevent discrepancies, we used the same stably infected LV-Wincr1 lines in all functional assays (characterized in Figure 5A). Two different dermal fibroblast lines with over-expression of Wincr1 had comparable rates of proliferation to controls over 7 days (Supplementary Figure S8). Next, we used an in vitro scratch assay to study the rate of collective cell migration of dermal fibroblasts in a wound healing setting. This multistep process is relevant in many biological processes such as embryonic development and wound healing (Liang et al., 2007). Compared to control, LV-Wincr1 had attenuated collective cell migration into the cleared area in both serum containing (Supplementary Figure S8) and serum-free conditions within 14–22 h (Figures 6A,B).

FIGURE 6.

Wincr1 function in collective cell migration and fibrotic response. (A) Dermal fibroblasts with LV-Wincr1 exhibit decreased migration compared to uninfected controls. (B) Migration is significantly diminished after 22 h following a scratch in serum-free media (n = 3) and representative of three separate experiments. (C,D) Type I collagen gel contraction assay demonstrates LV-Wincr1 fibroblasts have a higher ability to process collagen. The difference in collagen shrinkage is visible and consistent across three technical replicates from two independent cell lines by 14 h. Points represent the quantitation of collagen gel area normalized to plate area after 14 h using ImageJ software (n = 2 between Control and LV-Wincr1 at 14 h). ∗∗∗P-value ≤ 0.001.

Collagen type1 gel embedded with fibroblasts is considered an in vitro model for fibrotic process and matrix turnover (Fang et al., 2004). We determined whether Wincr1 affects the ability of dermal fibroblasts for collagen contraction, a key fibroblast function. We embedded control and LV-Wincr1 cells in type I rat tail collagen for 48 h to increase the mechanical load and then released the gels. We found LV-Wincr1 dermal fibroblasts had much higher capacity for processing collagen than controls (Figures 6C,D). The difference in collagen gel shrinkage by 14 h was significant and consistent across the two LV-Wincr1 cell lines. Thus, gain of function Wincr1 positively correlated with collagen gel contraction, thereby linking Wincr1 to a key fibroblast functionality.

In summary, we have identified key mRNAs and lncRNAs that are responsive to Wnt/β-catenin signaling levels and we have demonstrated that a lncRNA responsive to Wnt/β-catenin activity, Wincr1, is a potentially new regulator of dermal fibroblast behavior and ECM-related gene expression.

Discussion

Long non-coding RNAs have emerged as key regulators of many cellular processes, and their dysregulation has been observed in many human diseases (Wan and Wang, 2014). Studies of novel lncRNAs have led to the discovery of new mechanisms of gene regulation paving the way toward novel therapeutic strategies. In our current study, through the genetic stabilization of β-catenin in primary dermal fibroblasts, we identified downstream lncRNAs and mRNAs responsive to Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Our genetically targeted culture systems enabled us to observe the effects of β-catenin’s activity levels on gene expression in dermal fibroblasts without the paracrine influences of other cell types that would be present in whole skin expression analysis. Utilizing this system, we have identified Wnt/β-catenin signaling-induced lncRNAs such as Wincr1, that act as putative regulators of key genes such as Mmp10 and Col1a1 in ECM biology. Wincr1 also affects complex cellular behaviors such as collective cell migration and collagen processing and contraction.

Our expression profiling study allowed us to identify genes that were under the influence of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in dermal fibroblasts. Consistent with our previous gene expression analysis from mouse fibrotic dermis after 21 days of sustained Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Hamburg-Shields et al., 2015), gene ontology analysis through functional clustering shows a strong enrichment of ECM and ECM-regulatory gene expression within 72 h of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in dermal fibroblasts. Our analysis also implies that downstream targets of Wnt/β-catenin signaling may alter matrix deposition, remodeling, and fibroblast behavior. Comparison of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation gene signature in dermal fibroblasts with those dysregulated in various contexts of human fibrotic diseases confirms that the gene expression signature of β-catenin stabilization in our model is indeed relevant to human fibrotic disease. Thus, β-catenin stabilization in dermal fibroblasts is a relevant signaling pathway in matrix construction and remodeling and a relevant node for therapeutic intervention.

Analysis of the gene expression signature induced by β-catenin stabilization reveals enrichment for PRC2 targets, signifying epigenetic regulation. Unbiased gene set enrichment analysis of genes expressed in dermal fibroblasts shows an enrichment of PRC2 targets. This epigenetic regulatory repressive complex has been shown to interact with lncRNAs, suggesting that a portion of the β-catenin-dependent expression signature controlling ECM and fibrosis-related genes may be regulated by PRC2 or other mechanisms (Rinn and Chang, 2012; Wan and Wang, 2014). While further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism of β-catenin’s influence on fibrotic genes, these analyses of the coding gene changes following β-catenin activation guided our identification of novel lncRNAs as regulators of gene expression and fibroblast behavior.

Using sustained and inducible-reversible systems of Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation, Wincr1 was identified as a Wnt/β-catenin signaling induced lncRNA candidate due to its consistent response to β-catenin activity levels in multiple contexts in mouse dermal fibroblasts. Further context-specific functional roles of Wincr1 will be elucidated in future in vivo studies with fibroblast-restricted mutants. Our in vitro modulations of Wincr1 expression levels in dermal fibroblasts demonstrated that this lncRNA has a robust gene regulatory effect on distinct genes. Identification of other Wincr1 targets will require extensive expression profiling in dermal fibroblasts and other cell types. In addition, our studies reveal that β-catenin stabilization and overexpression of Wincr1 do not synergize to increase Mmp10 levels, suggesting that β-catenin and Wincr1 may function linearly in a uncharacterized genetic or epigenetic pathway to modulate key genes in matrix production and turnover. Our current data show that while Wincr1 levels are increased after stabilizing β-catenin, Wincr1 can also independently regulate expression of protein coding genes. Identifying other Wincr1 targets will allow us to further refine our understanding of how Wincr1 intersects with Wnt/β-catenin signaling for gene regulation and fibroblast cell behavior. In our current study, we elaborate on the role of Wincr1 in fibroblast gene regulation and cellular behavior, given that this is a context in which Wnt/β-catenin signaling is known to be important.

Our query of several fibrotic genes suggests that Wincr1 has a restricted gene regulatory role. Specifically, Mmp10 expression was consistently responsive to Wincr1 levels, suggesting it is a putative regulatory target of this novel lncRNA. Wincr1’s gene regulatory role does not appear to be pan-ECM, but instead can regulate a defined set of genes. Further mechanistic-based experiments are required to gain insight into how Wincr1 regulates Mmp10, and such studies would be helpful in predicting other targets through binding motifs or other means. Mmp10/Stromelysin-2 has emerged as a key player in fibrosis and “degradomics” (Overall and Kleifeld, 2006; Schlage et al., 2015; Sokai et al., 2015). MMPs can promote collagen contraction by increasing turnover (Daniels et al., 2003; Bildt et al., 2009), and we found increased contractile behavior in LV-Wincr1 dermal fibroblasts. Mmp10 is not a collagenase, but it has the ability to regulate expression of other MMPs, such as Mmp13, that have collagenolytic function and promote the resolution of matrix in wound healing. It is not clear if Mmp10 has a similar role in mitigating ECM accumulation in chronic fibrosis settings that are the result of excessive ECM production and inadequate resolution (McKleroy et al., 2013; Rohani et al., 2015). It is tempting to speculate that Wincr1 participates as a negative feedback to the pro-fibrotic Wnt/β-catenin pathway in dermal fibroblasts. Future functional studies with Wincr1 in fibrosis models will be needed to demonstrate if it has a fibroprotective function.

Wnt/β-catenin signaling has diverse roles in skin development, tissue homeostasis, and disease. Thus, identifying new genetic and epigenetic regulatory mechanisms will provide novel insight in our understanding of this important pathway in dermal fibroblasts. Discovery of this lncRNA and its preliminary regulatory links to β-catenin signaling, skin development, and known fibrotic protein-coding gene expression indicate that lncRNAs may play an important regulatory role in directing Wnt/β-catenin signaling. This is of particular interest in the context of fibrosis, a condition that can be caused by activation of this pathway, but with gene regulatory intermediates that will require further characterization in order to be of clinical value. The robust responsiveness of Wincr1 to Wnt/β-catenin signaling indicates the possibility of this and other lncRNAs as targets for therapeutic intervention to treat fibrosis, but also as circulating diagnostic biomarkers (Tang et al., 2015; Vencken et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2015). Further studies are needed to elucidate the gene regulatory mechanism and in vivo functions of Wincr1 and other β-catenin responsive lncRNAs. Also, mechanistic understanding into Wincr1 may lead to novel insights into the Wnt signaling pathway and how it regulates key genetic networks throughout embryonic development and adult diseases.

Author Contributions

NKM, NVM, RA, and AK contributed to experimental design, experiment collection, analysis, writing, and figure preparation. EH-S contributed to experimental design and writing of the manuscript. BI contributed to analysis.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank to past and current members of the Atit laboratory for excellent discussion and advice. Thanks to Gregg DiNuoscio and Anna Jussila for technical support. Thanks to the Case Genomics Core and Bioinformatics Core Services (Dr. Ricky Chan).

Funding. This research was partially supported by the Case Western Reserve University Skin Diseases Research Center Pilot and Feasibility Program (NIH P30 AR039750). This work was supported by the following grants: NIH-NIDCR-R01DE01870 (RA), Global Fibrosis Foundation (RA), NIBIB:1P41EB021911-01 (AK), NIH-NIA F30 AG045009 (EH-S), GAANN Fellowship (BI), Case Western Reserve University ENGAGE (NVM) and SOURCE Programs (NKM).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2017.00183/full#supplementary-material

Heatmaps of all lncRNAs and mRNAs expressed above 1FPKM. Biological replicates cluster together on the basis of global expression for both (A) lncRNA and (B) mRNAs by Pearson correlation (based on entities and samples).

Enrichment of predicted transcription factor binding site (TFBS) analysis on promoters of mRNA. Enrichment of TFBS within 5 Kb of the transcriptional start site (TSS) of up-regulated (A) and differentially expressed (P-value = 0.05, fold change > 2) (B) mRNAs after activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Statistically enriched TFBS (upper right quadrant) are not in the TCF/LEF family of transcription factors associated with Wnt signaling pathway (red color in A).

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) shows strong enrichment in Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) targets among genes up-regulated after β-catenin stabilization. (A–E) Top enriched gene sets from C2 database are Suz12, EED, and PRC2 targets, as well as H3 methylation sites. Gene sets enriched in the β-catenin stabilized GOF condition were plotted based on FWER P-value and Normalized Enrichment Score. (F) Leading edge analysis of the top four gene sets show common genes driving the enrichment of these signatures in GOF dermal fibroblasts.

LncRNA Wincr2 is differentially expressed in response to β-catenin activity at E13.5. (A) Endogenous expression of Wincr2 within distinct tissues from an E13.5 wild type embryo via qRT-PCR. Steady state mRNA expression level was verified across two independent embryonic litters. (B) Relative quantity of Wincr2 in E13.5 β-catistab cultured cranial and dorsal dermal fibroblasts after 4 days of β-catenin stabilization. (C) Wincr2 expression is not significantly altered after inducing β-catenin stabilization.

Co-expression network of genes up-regulated in β-catenin GOF and included in mouse Matrisome. Network includes all genes up-regulated (P-value < 0.05, fold change > 2) in GOF samples and included in the mouse Matrisome. Network edges indicate expression correlation between genes, with correlation coefficient above 0.6 shown. Network is separated into clusters based on correlation with Axin2 expression, or absence of such correlation (to the right).

Manipulation of Wincr1 expression does not affect all pro-fibrotic genes. (A–G) Expression of additional matrisome genes as a result of Wincr1 overexpression. We identified these mRNA targets from the analysis of our dataset, co-expression network generation, known fibroblast identity markers, matrisome gene targets, and literature screens.

Lack of synergistic expression of Mmp10 in cells with LV-Wincr1 and LV-Wincr1+ βcatistab. (A) Axin2 mRNA levels, a measure of β-catenin activation, is significantly higher in βcatistab condition (P-value = 0.0152, n = 2). (B) Wincr1 level is significantly higher in LV-Wincr1 and LV-Wincr1+ βcatistab samples (n = 2).(C) There is no significant difference in relative quantity of Mmp10 and Col1a1 mRNA between LV-Wincr1 and LV-Wincr1+ βcatistab samples, (n = 2). (C,D) Relative quantity of Col1a1 mRNA is significantly reduced in the presence of LV-Wincr1 (P-value = 0.0023, n = 2). Representative of three different experiments. ∗P-value ≤ 0.05, ∗∗P-value ≤ 0.01.

Overexpression of Wincr1 does not affect fibroblast proliferation. (A) Proliferation curve of control and LV-Wincr1 infected primary dermal fibroblasts showing comparable rate of proliferation (n = 3) and representative of two different experiments. (B) Migration is significantly diminished after 15 h following a scratch in the monolayer of LV-Wincr1 cells in serum-free media (n = 3) and representative of two separate experiments.

References

- Akhmetshina A., Palumbo K., Dees C., Bergmann C., Venalis P., Zerr P., et al. (2012). Activation of canonical Wnt signalling is required for TGF–β–mediated fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 3:735. 10.1038/ncomms1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allocco D. J., Kohane I. S., Butte A. J. (2004). Quantifying the relationship between co-expression, co-regulation and gene function. BMC Bioinformatics 5:18. 10.1186/1471-2105-5-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atit R., Sgaier S. K., Mohamed O. A., Taketo M. M., Dufort D., Joyner A. L., et al. (2006). β-catenin activation is necessary and sufficient to specify the dorsal dermal fate in the mouse. Dev. Biol. 296 164–176. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belteki G., Haigh J., Kabacs N., Haigh K., Sison K., Costantini F., et al. (2005). Conditional and inducible transgene expression in mice through the combinatorial use of Cre-mediated recombination and tetracycline induction. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 1–10. 10.1093/nar/gni051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bildt M. M., Bloemen M., Kuijpers-Jagtman A. M., Von den Hoff J. W. (2009). Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors reduce collagen gel contraction and alpha-smooth muscle actin expression by periodontal ligament cells. J. Periodontal Res. 44 266–274. 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2008.01127.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budnick I., Hamburg-Shields E., Chen D., Torre E., Jarrell A., Akhtar-Zaidi B., et al. (2016). Defining the identity of mouse embryonic dermal fibroblasts. Genesis 54 415–430. 10.1002/dvg.22952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H. Y., Chi J.-T., Dudoit S., Bondre C., van de Rijn M., Botstein D., et al. (2002). Diversity, topographic differentiation, and positional memory in human fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 12877–12882. 10.1073/pnas.162488599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D., Jarrell A., Guo C., Lang R., Atit R. (2012). Dermal β-catenin activity in response to epidermal Wnt ligands is required for fibroblast proliferation and hair follicle initiation. Development 139 1522–1533. 10.1242/dev.076463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels J. T., Cambrey A. D., Occleston N. L., Garrett Q., Tarnuzzer R. W., Schultz G. S., et al. (2003). Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition modulates fibroblast-mediated matrix contraction and collagen production in vitro. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44 1104–1110. 10.1167/iovs.02-0412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eames B. F., Schneider R. A. (2005). Quail-duck chimeras reveal spatiotemporal plasticity in molecular and histogenic programs of cranial feather development. Development 132 1499–1509. 10.1242/dev.01719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enzo M. V., Rastrelli M., Rossi C. R., Hladnik U., Segat D. (2015). The Wnt/β-catenin pathway in human fibrotic-like diseases and its eligibility as a therapeutic target. Mol. Cell. Ther. 3:1. 10.1186/s40591-015-0038-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Shen B., Tan M., Mu X., Qin Y., Zhang F., et al. (2014). Long non-coding RNA UCA1 increases chemoresistance of bladder cancer cells by regulating Wnt signaling. FEBS J. 281 1750–1758. 10.1111/febs.12737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Q., Liu X., Abe S., Kobayashi T., Wang X. Q., Kohyama T., et al. (2004). Thrombin induces collagen gel contraction partially through PAR1 activation and PKC-ɛ. Eur. Respir. J. 24 918–924. 10.1183/09031936.04.00005704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J., Jiang M., Mirando A. J., Yu H. M., Hsu W. (2009). Reciprocal regulation of Wnt and Gpr177/mouse Wntless is required for embryonic axis formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 18598–18603. 10.1073/pnas.0904894106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X.-L., Liu D.-J., Yan T.-T., Yang J.-Y., Yang M.-W., Li J., et al. (2016). Analysis of long non-coding RNA expression profiles in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 6:33535. 10.1038/srep33535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburg E. J., Atit R. P. (2012). Sustained Beta-Catenin activity in dermal fibroblasts is sufficient for skin fibrosis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 132 2469–2472. 10.1038/jid.2012.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburg-Shields E., DiNuoscio G. J., Mullin N. K., Lafayatis R., Atit R. P. (2015). Sustained β-catenin activity in dermal fibroblasts promotes fibrosis by up-regulating expression of extracellular matrix protein-coding genes. J. Pathol. 235 686–697. 10.1002/path.4481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada N., Tamai Y., Ishikawa T.-O., Sauer B., Takaku K., Oshima M., et al. (1999). Intestinal polyposis in mice with a dominant stable mutation of the beta-catenin gene. EMBO J. 18 5931–5942. 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z., Feng L., Zhang X., Geng Y., Parodi D. A., Suarez-Quian C., et al. (2005). Expression of Col1a1 Col1a2 and procollagen I in germ cells of immature and adult mouse testis. Reproduction 130 333–341. 10.1530/rep.1.00694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Sui S. J., Fulton D. L., Arenillas D. J., Kwon A. T., Wasserman W. W. (2007). OPOSSUM: integrated tools for analysis of regulatory motif over-representation. Nucleic Acids Res. 35(Suppl. 2) W245–W252. 10.1093/nar/gkm427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Yang Y., Liu L. (2015). Interaction of long noncoding RNAs and microRNAs in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Physiol. Genomics 47 463–469. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00064.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jho E.-H., Zhang T., Domon C., Joo C.-K., Freund J.-N., Costantini F. (2002). Wnt/beta-catenin/Tcf signaling induces the transcription of Axin2 a negative regulator of the signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 1172–1183. 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil A. M., Guttman M., Huarte M., Garber M., Raj A., Rivea Morales D., et al. (2009). Many human large intergenic noncoding RNAs associate with chromatin-modifying complexes and affect gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 11667–11672. 10.1073/pnas.0904715106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel R. A., Turnbull D. H., Blanquet V., Wurst W., Loomis C. A., Joyner A. L. (2000). Two lineage boundaries coordinate vertebrate apical ectodermal ridge formation. Genes Dev. 14 1377–1389. 10.1101/gad.14.11.1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon A. T., Arenillas D. J., Worsley Hunt R., Wasserman W. W. (2012). oPOSSUM-3: advanced analysis of regulatory motif over-representation across genes or ChIP-Seq datasets. G3 (Bethesda) 2 987–1002. 10.1534/g3.112.003202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam A. P., Gottardi C. J. (2011). β-catenin signaling. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 23 562–567. 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32834b3309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C.-C., Park A. Y., Guan J.-L. (2007). In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2 329–333. 10.1038/nprot.2007.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim X., Nusse R. (2012). Wnt signaling in skin development, homeostasis, and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5:a008029. 10.1101/cshperspect.a008029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-ΔΔCT) Method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Yang Y., Wang F., Moyer M.-P., Wei Q., Zhang P., et al. (2016). Long non-coding RNA CCAL regulates colorectal cancer progression by activating Wnt/beta-catenin signalling pathway via suppression of activator protein 2α. Gut 65 1494–1504. 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrogiannaki M., Lichtenberger B. M., Reimer A., Collins C. A., Driskell R. R., Watt F. M. (2016). β-Catenin stabilization in skin fibroblasts causes fibrotic lesions by preventing adipocyte differentiation of the reticular dermis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 136 1130–1142. 10.1016/j.jid.2016.01.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrea P. D., Gottardi C. J. (2016). Beyond β-catenin: prospects for a larger catenin network in the nucleus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17 55–64. 10.1038/nrm.2015.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKleroy W., Lee T.-H., Atabai K. (2013). Always cleave up your mess: targeting collagen degradation to treat tissue fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung. Cell Mol. Physiol. 304 L709–L721. 10.1152/ajplung.00418.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheletti R., Plaisance I., Abraham B. J., Sarre A., Ting C.-C., Alexanian M., et al. (2017). The long noncoding RNA Wisper controls cardiac fibrosis and remodeling. Sci. Transl. Med. 9:eaai9118. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aai9118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mootha V. K., Lindgren C. M., Eriksson K.-F., Subramanian A., Sihag S., Lehar J., et al. (2003). PGC-1α-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately down-regulated in human diabetes. Nat. Genet. 34 267–273. 10.1038/ng1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran V. A., Niland C. N., Khalil A. M. (2012). Co-Immunoprecipitation of long noncoding RNAs. Methods Mol. Biol. 925 219–228. 10.1007/978-1-62703-011-3_15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A., Soyal S. M., Li J., Ying Y., Szwarc M. M., He B., et al. (2010). A mouse transgenic approach to induce β-catenin signaling in a temporally controlled manner. Transgenic Res. 20 827–840. 10.1007/s11248-010-9466-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naba A., Clauser K. R., Hoersch S., Liu H., Carr S. A., Hynes R. O. (2012). The matrisome: in silico definition and in vivo characterization by proteomics of normal and tumor extracellular matrices. Mol. Cell Proteomics 11:M111.014647. 10.1074/mcp.M111.014647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y., de Paiva Alves E., Veenstra G. J., Hoppler S. (2009). Tissue- and stage-specific Wnt target gene expression is controlled subsequent to β-catenin recruitment. Bioinformatics 143 1105–1111. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse R., Clevers H. (2017). Wnt/beta-Catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell 169 985–999. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtola J., Myers J., Akhtar-Zaidi B., Zuzindlak D., Sandesara P., Yeh K., et al. (2008). β-Catenin has sequential roles in the survival and specification of ventral dermis. Development 135 2321–2329. 10.1242/dev.021170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall C. M., Kleifeld O. (2006). Validating matrix metalloproteinases as drug targets and anti-targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6 227–239. 10.1038/nrc1821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccoli M.-T., Gupta S. K., Viereck J., Foinquinos A., Samolovac S., Kramer F. L., et al. (2017). Inhibition of the cardiac fibroblast–enriched lncRNA Meg3 prevents cardiac fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction novelty and significance. Circ. Res. 121 575–583. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X., Du Y., Shu Y., Gao M., Sun F., Luo S., et al. (2017). MIAT Is a Pro-fibrotic long non-coding RNA governing cardiac fibrosis in post-infarct myocardium. Sci. Rep. 7:42657. 10.1038/srep42657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendl M., Lewis L., Fuchs E. (2005). Molecular dissection of mesenchymal-epithelial interactions in the hair follicle. PLOS Biol. 3:e331. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinn J. L., Chang H. Y. (2012). Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. arXiv 81 145–166. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051410-092902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohani M. G., McMahan R. S., Razumova M. V., Hertz A. L., Cieslewicz M., Pun S. H., et al. (2015). MMP-10 regulates collagenolytic activity of alternatively activated resident macrophages. J. Invest. Dermatol. 135 2377–2384. 10.1038/jid.2015.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlage P., Kockmann T., Sabino F., Kizhakkedathu J. N., Auf dem Keller U. (2015). Matrix metalloproteinase 10 degradomics in keratinocytes and epidermal tissue identifies bioactive substrates with pleiotropic functions. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 14 3234–3246. 10.1074/mcp.M115.053520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen T. D., Livak K. J. (2008). Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 3 1101–1108. 10.1038/nprot.2008.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C. A., Rasband W. S., Eliceiri K. W. (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9 671–675. 10.1038/nmeth.2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuijers J., Mokry M., Hatzis P., Cuppen E., Clevers H. (2014). Wnt-induced transcriptional activation is exclusively mediated by TCF/LEF. EMBO J. 33 146–156. 10.1002/embj.201385358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N. S., Wang J. T., Ramage D., et al. (2003). Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13 2498–2504. 10.1101/gr.1239303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokai A., Handa T., Tanizawa K., Oga T., Uno K., Tsuruyama T., et al. (2015). Matrix metalloproteinase-10: a novel biomarker for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 16 120. 10.1186/s12931-015-0280-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V. K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B. L., Gillette M. A., et al. (2005). Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 15545–15550. 10.1073/pnas.0506580102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J., Jiang R., Deng L., Zhang X., Wang K., Sun B. (2015). Circulation long non-coding RNAs act as biomarkers for predicting tumorigenesis and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 6 4505–4515. 10.18632/oncotarget.2934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran T. H., Jarrell A., Zentner G. E., Welsh A., Brownell I., Scacheri P. C., et al. (2010). Role of canonical Wnt signaling/β-catenin via Dermo1 in cranial dermal cell development. Development 137 3973–3984. 10.1242/dev.056473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Amerongen R. E. E., Nusse R. (2009). Towards an integrated view of Wnt signaling in development. Development 136 3205–3214. 10.1242/dev.033910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassallo I., Zinn P., Lai M., Rajakannu P., Hamou M.-F., Hegi M. E. (2015). WIF1 re-expression in glioblastoma inhibits migration through attenuation of non-canonical WNT signaling by downregulating the lncRNA MALAT1. Oncogene 35 12–21. 10.1038/onc.2015.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vencken S. F., Greene C. M., Mckiernan P. J. (2015). Non-coding RNA as lung disease biomarkers. Thorax 70 501–503. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan D. C., Wang K. C. (2014). Long Noncoding RNA: significance and potential in skin biology. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 4:a015404. 10.1101/cshperspect.a015404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Reid Sutton V., Omar Peraza-Llanes J., Yu Z., Rosetta R., Kou Y. C., et al. (2007). Mutations in X-linked PORCN, a putative regulator of Wnt signaling, cause focal dermal hypoplasia. Nat. Genet. 39 836–838. 10.1038/ng2057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Chen R., Correspondence Z. F. (2015). The Long Noncoding RNA lncTCF7 promotes self- renewal of human liver cancer stem cells through activation of Wnt signaling. Stem Cell 16 413–425. 10.1016/j.stem.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Jinnin M., Nakamura K., Harada M., Kudo H., Nakayama W., et al. (2016). Long non-coding RNA TSIX is up-regulated in scleroderma dermal fibroblasts and controls collagen mRNA stabilization. Exp. Dermatol. 25 131–136. 10.1111/exd.12900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Yin C., Dang Y., Ye F., Zhang G. (2015). Identification of the long non- coding RNA H19 in plasma as a novel biomarker for diagnosis of gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 5:11516. 10.1038/srep11516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu P., Wang Y., Huang G., Ye B., Liu B., Wu J., et al. (2016). lnc-β-Catm elicits EZH2-dependent β-catenin stabilization and sustains liver CSC self-renewal. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23 631–639. 10.1038/nsmb.3235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Heatmaps of all lncRNAs and mRNAs expressed above 1FPKM. Biological replicates cluster together on the basis of global expression for both (A) lncRNA and (B) mRNAs by Pearson correlation (based on entities and samples).

Enrichment of predicted transcription factor binding site (TFBS) analysis on promoters of mRNA. Enrichment of TFBS within 5 Kb of the transcriptional start site (TSS) of up-regulated (A) and differentially expressed (P-value = 0.05, fold change > 2) (B) mRNAs after activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Statistically enriched TFBS (upper right quadrant) are not in the TCF/LEF family of transcription factors associated with Wnt signaling pathway (red color in A).

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) shows strong enrichment in Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) targets among genes up-regulated after β-catenin stabilization. (A–E) Top enriched gene sets from C2 database are Suz12, EED, and PRC2 targets, as well as H3 methylation sites. Gene sets enriched in the β-catenin stabilized GOF condition were plotted based on FWER P-value and Normalized Enrichment Score. (F) Leading edge analysis of the top four gene sets show common genes driving the enrichment of these signatures in GOF dermal fibroblasts.

LncRNA Wincr2 is differentially expressed in response to β-catenin activity at E13.5. (A) Endogenous expression of Wincr2 within distinct tissues from an E13.5 wild type embryo via qRT-PCR. Steady state mRNA expression level was verified across two independent embryonic litters. (B) Relative quantity of Wincr2 in E13.5 β-catistab cultured cranial and dorsal dermal fibroblasts after 4 days of β-catenin stabilization. (C) Wincr2 expression is not significantly altered after inducing β-catenin stabilization.

Co-expression network of genes up-regulated in β-catenin GOF and included in mouse Matrisome. Network includes all genes up-regulated (P-value < 0.05, fold change > 2) in GOF samples and included in the mouse Matrisome. Network edges indicate expression correlation between genes, with correlation coefficient above 0.6 shown. Network is separated into clusters based on correlation with Axin2 expression, or absence of such correlation (to the right).

Manipulation of Wincr1 expression does not affect all pro-fibrotic genes. (A–G) Expression of additional matrisome genes as a result of Wincr1 overexpression. We identified these mRNA targets from the analysis of our dataset, co-expression network generation, known fibroblast identity markers, matrisome gene targets, and literature screens.

Lack of synergistic expression of Mmp10 in cells with LV-Wincr1 and LV-Wincr1+ βcatistab. (A) Axin2 mRNA levels, a measure of β-catenin activation, is significantly higher in βcatistab condition (P-value = 0.0152, n = 2). (B) Wincr1 level is significantly higher in LV-Wincr1 and LV-Wincr1+ βcatistab samples (n = 2).(C) There is no significant difference in relative quantity of Mmp10 and Col1a1 mRNA between LV-Wincr1 and LV-Wincr1+ βcatistab samples, (n = 2). (C,D) Relative quantity of Col1a1 mRNA is significantly reduced in the presence of LV-Wincr1 (P-value = 0.0023, n = 2). Representative of three different experiments. ∗P-value ≤ 0.05, ∗∗P-value ≤ 0.01.

Overexpression of Wincr1 does not affect fibroblast proliferation. (A) Proliferation curve of control and LV-Wincr1 infected primary dermal fibroblasts showing comparable rate of proliferation (n = 3) and representative of two different experiments. (B) Migration is significantly diminished after 15 h following a scratch in the monolayer of LV-Wincr1 cells in serum-free media (n = 3) and representative of two separate experiments.