Abstract

Objective:

This article reports on the development, implementation, and evaluation of an integrative clinical oncology massage program for patients undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer in a large academic medical center.

Materials and Methods:

We describe the development and implementation of an oncology massage program embedded into chemoinfusion suites. We used deidentified program evaluation data to identify specific reasons individuals refuse massage and to evaluate the immediate impact of massage treatments on patient-reported outcomes using a modified version of the Distress Thermometer delivered via iPad. We analyzed premassage and postmassage data from the Distress Thermometer using paired t test and derived qualitative data from participants who provided written feedback on their massage experiences.

Results:

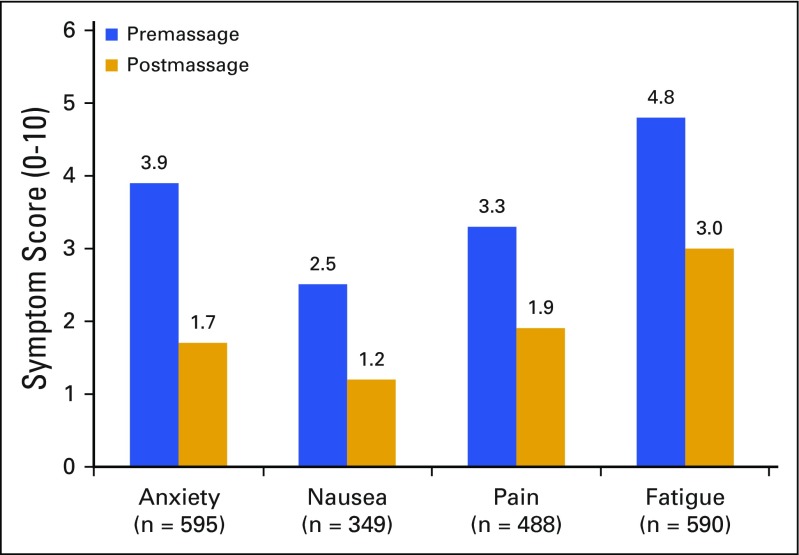

Of the 1,090 massages offered, 692 (63%) were accepted. We observed a significant decrease in self-reported anxiety (from 3.9 to 1.7), nausea (from 2.5 to 1.2), pain (from 3.3 to 1.9), and fatigue (from 4.8 to 3.0) premassage and postmassage, respectively (all P < .001). We found that 642 survey participants (93%) were satisfied with their massage, and 649 (94%) would recommend it to another patient undergoing treatment. Spontaneous patient responses overwhelmingly endorsed the massage as relaxing. No adverse events were reported. Among the 398 patients (36%) who declined a massage, top reasons were time concerns and lack of interest.

Conclusion:

A clinical oncology massage program can be safely and effectively integrated into chemoinfusion units to provide symptom control for patients with breast cancer. This integrative approach overcomes patient-level barriers of cost, time, and travel, and addresses the institutional-level barrier of space.

INTRODUCTION

In 2015, approximately 234,000 cases of breast cancer were diagnosed in the United States.1 Cancer diagnosis and its initial surgical treatment are usually accompanied by anxiety, depression, and stress.2,3 Chemotherapy can result in fatigue, nausea, and sleep disruption.4,5 Although conventional approaches exist for many of these symptoms, they are often insufficient. Patients with cancer increasingly desire complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for relief from symptoms that have not been addressed by conventional treatments.6-8 In fact, cancer survivors are more likely to use CAM than the general population and to use it for general wellness, immune enhancement, and pain.9,10

Preliminary research suggests that massage, a common CAM therapy, may benefit cancer populations. In a study of 1,290 patients participating in a massage program at a major cancer center, Cassileth and Vickers11 found a 50% reduction in pain, fatigue, stress/anxiety, nausea, and depression. A recent Cochrane review of 19 studies including 1,274 participants found that massage may reduce pain and anxiety in the short term in patients with cancer, although the quality of evidence was low.12 Among patients with breast cancer, massage produced significant improvements in state and trait anxiety, sleep, and functional well-being for patients undergoing radiation and/or chemotherapy.13 Massage has also been found to decrease patients’ depression,14,15 anger, and hostility levels,16 and improve nausea.17

Massage therapy is well accepted, but has low utilization rates. In our group’s previous study, although 58% of patients with early-stage breast cancer endorsed the integration of massage services into academic cancer centers, only 22% reported having used massage since their cancer diagnosis.18 Given the relatively low rate of massage use among patients with breast cancer,7,19 in 2015, the University of Pennsylvania’s Abramson Cancer Center (ACC) piloted an oncology massage program in collaboration with the local, nonprofit, 501(c)3 organization, Unite for HER (UFH). The program offers patients with breast cancer a form of massage modified for safe application and provided by trained oncology massage therapists in the chemotherapy suites.20 From August 2015 to April 2016, the program’s licensed massage therapists delivered 692 treatments. In this article, we report on the program’s development and implementation. As part of the program outcome evaluation, we collected data for the following specific aims: (1) to evaluate the short-term effects of massage on anxiety, pain, nausea, and fatigue among patients with breast cancer; (2) to identify through comments the salient experiences of patients with breast cancer receiving massage; and (3) to identify the reasons patients decline massage services. The conceptual framework guiding our evaluation of massage on common symptom outcomes was based on clinician input, review of the literature,11 and the biopsychosocial effect of massage that may target common biobehavioral pathways of behavioral symptoms.21

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Academic Medical Center and Community Nonprofit Collaboration

J.J.M. (the first author) met with the leadership of UFH to discuss the steps necessary to bring an oncology massage program to an academic medical center. Based in southeastern Pennsylvania, UFH provides vouchers for patients with breast cancer to receive integrative therapies, including oncology massage. UFH previously found that despite addressing cost barriers, many women with breast cancer do not fully use integrative services because of time and travel concerns. ACC and UFH collaborated to develop and implement a novel program that delivered oncology massage in the cancer center. Program development required joining stakeholders from the nonprofit, academic research, and patient care realms. Through this collaboration, we sought to enhance the clinical care of oncology patients aligned with the mission of UFH and ensure that resources and expertise were available for critical program evaluation and research through our academic cancer center.

Implementation

Our implementation plan involved exploration, identification of program needs, planning, initial and full implementation, and program expansion. The goals of the exploration phase were to identify program need, leadership, and funding sources. Next, we developed a more detailed plan and timeline, established contracts with massage therapists, engaged key stakeholders from operations and clinical teams to address program concerns, and prepared our initial survey tools and printed materials. We then implemented the initial phase of our program, offering it once a week to ensure that the integration of massage into clinical care was running smoothly and to troubleshoot unanticipated complications. We revised our survey tools, hired a second therapist, and expanded our massage therapist training to include appropriate use of electronic medical records, allowing therapists to be more self-sufficient. On program expansion, we further streamlined our processes by creating an electronic survey delivered via iPads that allowed for more extensive data collection with fewer personnel. The final phase involved continuing the current clinical program while exploring expansion to other patient populations and centers. We obtained institutional review board approval to report on our outcomes and initial results.

Clinical Massage Program Description

Before establishing employment with our program, licensed massage therapists completed a 24-hour credit course in advanced training for oncology massage technique approved by the Society for Oncology Massage. We started with one massage therapist once a week for the first month, two massage therapists 3 days per week for the next 4 months, and finally increased to three massage therapists 5 days per week. Sessions lasted approximately 20 minutes (range, 15-30 min) depending on patient preference and availability. Although our massage therapists individualized treatment regimens, they generally administered a lower extremity or head and neck massage (Table 1). They carefully tailored the pressure of these therapeutic treatments to each patient and only used light or very light compressions to avoid unanticipated adverse effects of massage.

Table 1.

Massage Operating Procedure and Protocol

We distributed printed educational materials on the floor where the massages were administered. Patients could request or consent to a session when offered by a practitioner. Not all patients who were offered this free service elected to receive it. We asked patients who declined to use an iPad to indicate their reasons. Patients requesting multiple sessions during the course of their chemotherapy regimen on different days were able to receive them if the massage therapists could accommodate them.

Outcome Evaluation Process

As part of the program, we asked patients to complete a short assessment of their symptoms and provide feedback on their experience on a patient-facing tablet-based survey assessment using the Qualtrics survey software (Qualtrics, Provo, Utah). We asked patients who declined services to provide their reasons for declining by choosing one of the following categories: “I am concerned about time,” “I am not interested,” “I am experiencing too much pain,” “I prefer not to be touched,” or “Other.” For those who chose to receive a massage, we provided a modified version of the Distress Thermometer (DT), a well-validated tool used to assess distress among patients with cancer. We modified the original tool for assessments of anxiety, pain, fatigue, and nausea; similar modification to assess emotional distress, anxiety, depression, and anger among patients with cancer has shown validity.22 Using touchscreen technology that allowed them to slide a thermometer across the screen to indicate their levels of distress from 0 (none) to 10 (extreme), patients responded to the following statement: “Please slide the scale to the number (0-10) that best describes how much distress you have been experiencing in the past week, including today.” There were a total of four thermometers, each addressing a unique symptom: anxiety, nausea, pain, and fatigue. Patients completed the thermometers before and after massages. After their massages, patients also completed two questions on satisfaction. For the first question, “How satisfied were you with the massage therapy program?” respondents were asked to rate their response on a five-point scale, from very satisfied to very dissatisfied. Next, respondents were asked whether they would recommend massage to other patients (yes or no). If the patient indicated she had received a prior massage with our program, she was asked two open-ended questions to elicit what was best about the program and how it could be improved. She was also asked, “Have you experienced any adverse effects from your massage treatment?” Although completing a survey was not required to receive a massage, our therapists were instructed to offer the survey to each participant and aid her in interacting with the touchscreen technology, if needed.

Outcome Evaluation Research

We obtained approval from the institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania and the ACC’s Clinical Trials Scientific Review and Monitoring Committee to use our anonymous program data to conduct outcome research. For quantitative analysis, we analyzed the pre–post data from the Distress Thermometer using a paired t test (P < .05 indicating statistical significance, two-sided). We derived qualitative data from the subset of participants who provided written feedback on their experiences of the massage sessions and generated a word cloud to visually represent the appearance of key words.

RESULTS

Study Population Description

All massages were delivered in the chemoinfusion suites to women receiving treatment for breast cancer. During the evaluation period between August 2015 and April 2016, we offered 1,090 massages. Of these, 692 (63%) were accepted. Among these patients, 184 (27%) were receiving a massage through our program for the first time, and 501 (73%) indicated that they had previously received a massage through our program. All participants who received a massage were asked whether they experienced any adverse effects; 91% answered no, and the 9% (57) who answered yes reported effects related to feeling relaxed. No negative adverse effects were reported. Among the 398 who declined a massage (36%), the top reasons were lack of interest (141; 36%) and time concerns (131; 33%), followed by not physically well/tired (70; 17.8%), prefer not to be touched (31; 7.9%), and other (20; 5.1%).

Immediate Symptom Reduction

According to analysis of 692 sessions, patients reported a significant decrease in anxiety (n = 595, from 3.9 [SD 2.5] to 1.7 [SD 1.8]), nausea (n = 349, from 2.5 [SD 2.6] to 1.2 [SD 1.9]), pain (n = 488, from 3.3 [SD 2.5] to 1.9 [SD 2.0]), and fatigue (n = 590, from 4.8 [SD 2.8] to 3.0 [SD 2.4]), with P < .001 for all (Fig 1). When we restricted analysis to first-time session patients (n = 184), results were similar. Using conservative estimates that treat missing data (6%) as not endorsing massage, we found that 642 of survey participants (93%) were satisfied or very satisfied with their massage and that 649 (94%) would recommend it to another patient undergoing treatment.

FIG 1.

Symptom changes before and after massage.

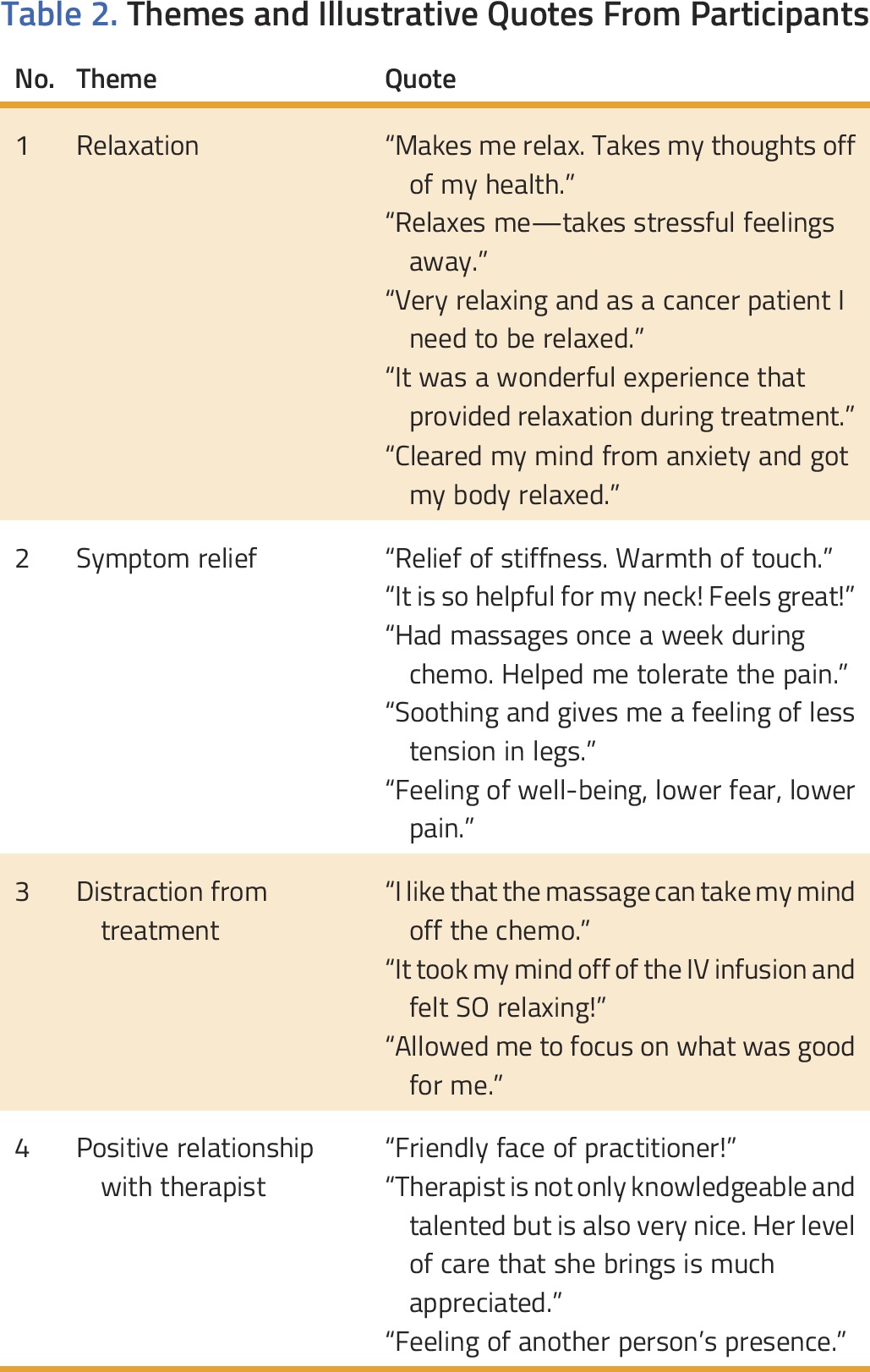

Patient Experiences in Their Words

A generated word cloud (Appendix Fig A1, online only) of spontaneous participant responses collected via iPad demonstrated that patients used the word relaxation most frequently to describe their massage experience. Content analysis of the data further revealed the following major recurrent themes: (1) relaxation, (2) symptom relief, (3) distraction, and (4) positive relationship with therapist (see Table 2 for sample quotes).

Table 2.

Themes and Illustrative Quotes From Participants

Basic Lessons

We learned a great deal in the processes of planning and implementation, including limiting the number of people who enter the patient’s chemotherapy suite to explain the program and that some people simply do not want a massage. We learned that the electronic program evaluation and patient-tracking platform using iPads decreased patient and provider burden in data tracking and outcome evaluation. It is also essential to have key stakeholders on board, a dedicated leader, a project manager, and qualified oncology massage–trained therapists.

DISCUSSION

Chemotherapy frequently causes substantial symptom burden, such as pain, anxiety, nausea, and fatigue for patients with breast cancer. Despite this population’s interest in using CAM to manage their symptoms, they often face barriers to accessing these services. In this study, we addressed these barriers and described the development, implementation, and evaluation of an integrative oncology massage program for patients with breast cancer in the chemoinfusion suites of a large, urban academic cancer center. We found that the program was feasible, was well liked, and produced substantial and immediate short-term reductions in pain, anxiety, nausea, and fatigue. Quantitative data indicate that 93% of participants reported feeling satisfied or very satisfied with their experience, and 94% would recommend massage to other patients with cancer undergoing treatment. Qualitative data suggest a relaxation response for most participants. Our findings provide initial evidence for successfully integrating this type of program into an urban academic cancer center.

Our study contributes to limited research on integrating massage into the oncology health care setting. Although not focused on chemotherapy, a large study (N = 1,290) evaluating massage therapy for inpatient and outpatient cancer populations that found similar improvements in symptom outcomes concluded that it is feasible to integrate a high-volume massage program in a major cancer center.11 A small Turkish study (N = 40), in which nurses provided back massage during patients’ chemotherapy appointments, also showed that massage was beneficial and demonstrated feasibility for integration into the outpatient setting, although it did not focus on patients with breast cancer.23 Nurse-administered massage would be challenging in the United States because nurses frequently manage medications, adhere to patient safety measures, and complete documentation. However, by integrating licensed oncology massage therapists into chemotherapy suites to work alongside nursing staff, these services become possible in the US health care system. To our knowledge, ours is the first large-scale study to investigate the integration of such a program for patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy in private outpatient chemoinfusion suites. Because chemoinfusion floors are increasingly designed with individual private rooms, we have a unique opportunity to offer massage and other integrative therapies to patients concurrent with their conventional treatment.

Our integrative massage program for patients with breast cancer produced significant immediate symptom improvements in pain, fatigue, anxiety, and nausea, and an increase in relaxation consistent with others who have published in this field.24-27 Survivors of breast cancer with cancer-related fatigue showed a significant decrease in fatigue and an improvement in mood after massage.24 Patients who received mastectomies at a hospital reported a significant reduction in pain, stress, and muscle tension, and an increase in relaxation immediately after receiving a massage.25 In a clinical trial for massage, patients with breast cancer (n = 34) reported significantly lower mood disturbances, especially for anger, anxious depression, and tiredness.26 In a systematic review to examine whether massage provided measureable benefit for breast cancer–related symptoms, patients receiving regular massage had significant reductions in anger and fatigue.27 Because our study examined immediate change without a control group, we do not know whether integration of massage in chemotherapy suites leads to persistent improvement in quality of life and symptom reduction over time. However, our results indicate it provides immediate short-term improvement for patients with breast cancer during a difficult period in their lives.

In response to accumulating evidence in cancer populations, the Society for Integrative Oncology has given massage therapy a grade B rating and recommends providing the modality because “there is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is a moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.”28(p350) Despite this recommendation, use of massage remains low, with only 22% of patients with breast cancer using massage since their diagnosis.18 Patients with cancer face a number of barriers to accessing supportive care services in the outpatient setting, including lack of awareness and physician nonreferral, lack of time, cost, and travel/transportation concerns.29-31 In addition, our recent research has found that transportation is a higher perceived barrier to CAM use for nonwhite patients with cancer compared with whites.32 Our study addressed these common barriers to accessing CAM services such as massage by removing patient-level barriers of cost, time, and travel that may otherwise have prevented them from accessing this service. We also addressed the significant system-level barrier of space by providing our program in chemoinfusion suites at the same time as a patient’s already-scheduled treatment.

Financial challenges often limit the development of this type of service for patients with cancer. Our initial program implementation was possible in part because of funding ($25,000) from our nonprofit partner. Because of the overwhelmingly positive responses from patients and systematically demonstrative outcomes, the program has since received ongoing funding from ACC and is expanding to include patients with gynecologic cancers. Because many academic and community cancer centers have foundations and relationships with nonprofit organizations and donors, creatively building partnerships, leveraging existing resources, and systematically collecting and demonstrating outcomes will allow innovative programs to be built. More effort is needed to conduct research and advance health policy leading to reimbursement for evidence-based therapies to improve patient experiences and outcomes.

Our study has several limitations. First, we used a convenience sample of patients who self-selected for massage sessions and outcome evaluation; thus, social desirability in response and missing data may introduce bias in estimating the magnitude of the benefit of massage. Second, we only evaluated the immediate changes that resulted from massage and cannot comment on any long-lasting benefits or changes. Third, although the Distress Thermometer has been widely used in many studies of patients with cancer, it is most commonly used longitudinally over longer periods of time and has not been fully validated to assess momentary changes in distress after an intervention. Fourth, because we did not have a control group, some of the quantitative changes could be due to regression to the mean effect; therefore, our results cannot be interpreted as definitive evidence of efficacy. Also, our study was only available to English speakers. Finally, because of the lack of evaluating key social demographic variables, such as race/ethnicity, we do not know whether disparities exist. Future research should address these limitations.

In conclusion, despite its limitations, our study provides the initial evidence that an oncology massage program can be safely and effectively integrated into chemoinfusion suites to provide symptom control for patients with breast cancer. This integrative approach overcomes patient-level barriers of cost, time, and travel, and addresses the institutional-level barrier of space. Our study also found that oncology massage may result in positive short-term reductions in symptoms and lead to increased relaxation. More rigorous research is needed to evaluate the impact of oncology massage on reducing symptoms, decreasing the need for additional medications, and improving adherence to chemotherapies. If collective research can demonstrate that massage improves patient experiences and outcomes, such a service can become a part of bundled oncology care, leading to sustainable integrative oncology practice for women with breast cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported in part by a research grant from Unite for HER and from the Integrative Medicine and Wellness Program Fund and the Rowan Breast Center Educational Fund, both from the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania. J.J.M. is funded in part by Abramson Cancer Center Core Grant No. 2P30CA016520-40 and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (No. 3P30CA008748-50). We thank massage therapists Eleanor Dukes, Danica Arizola, Ilia Stranko, and Julie Ackerman for their help in designing and delivering the interventions. We also thank Sue Weldon for her dedication to women with breast cancer and her input into our massage program. Sincere thanks go to the patients, oncologists, nurses, and clinical staff for their support of our study.

Appendix

FIG A1.

Word cloud from patients’ spontaneous written words.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Jun J. Mao, Christina M. Seluzicki

Financial support: Jun J. Mao

Provision of study materials or patients: Kevin R. Fox

Administrative support: Jun J. Mao, Karen E. Wagner

Collection and assembly of data: Karen E. Wagner, Audra Hugo, Laura K. Galindez

Data analysis and interpretation: Jun J. Mao, Audra Hugo, Heather Sheaffer, Kevin R. Fox

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Integrating Oncology Massage Into Chemoinfusion Suites: A Program Evaluation

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jop/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Jun J. Mao

No relationship to disclose

Karen E. Wagner

Honoraria: Springfield Psychological

Christina M. Seluzicki

No relationship to disclose

Audra Hugo

No relationship to disclose

Laura K. Galindez

No relationship to disclose

Heather Sheaffer

No relationship to disclose

Kevin R. Fox

Honoraria: Genomic Health

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genomic Health

REFERENCES

- 1. American Cancer Society: Cancer facts & figures 2013. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-036845.pdf.

- 2.Mehnert A, Koch U. Prevalence of acute and post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental disorders in breast cancer patients during primary cancer care: A prospective study. Psychooncology. 2007;16:181–188. doi: 10.1002/pon.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, et al. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: Five year observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330:702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38343.670868.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro CL, Recht A. Side effects of adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1997–2008. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106283442607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bovbjerg DH. The continuing problem of post chemotherapy nausea and vomiting: Contributions of classical conditioning. Auton Neurosci. 2006;129:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mao JJ, Cohen L. Advancing the science of integrative oncology to inform patient-centered care for cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2014;2014:283–284. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgu038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boon HS, Olatunde F, Zick SM. Trends in complementary/alternative medicine use by breast cancer survivors: Comparing survey data from 1998 and 2005. BMC Womens Health. 2007;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cutshall SM, Cha SS, Ness SM, et al. Symptom burden and integrative medicine in cancer survivorship. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:2989–2994. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2666-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao JJ, Palmer CS, Healy KE, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer survivors: A population-based study. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:8–17. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson JG, Taylor AG. Use of complementary therapies for cancer symptom management: Results of the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18:235–241. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cassileth BR, Vickers AJ. Massage therapy for symptom control: Outcome study at a major cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin ES, Seo KH, Lee SH, et al. Massage with or without aromatherapy for symptom relief in people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016:CD009873. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009873.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sturgeon M, Wetta-Hall R, Hart T, et al. Effects of therapeutic massage on the quality of life among patients with breast cancer during treatment. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:373–380. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Listing M, Reisshauer A, Krohn M, et al. Massage therapy reduces physical discomfort and improves mood disturbances in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:1290–1299. doi: 10.1002/pon.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krohn M, Listing M, Tjahjono G, et al. Depression, mood, stress, and Th1/Th2 immune balance in primary breast cancer patients undergoing classical massage therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1303–1311. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0946-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez-Reif M, Ironson G, Field T, et al. Breast cancer patients have improved immune and neuroendocrine functions following massage therapy. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:45–52. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Billhult A, Bergbom I, Stener-Victorin E. Massage relieves nausea in women with breast cancer who are undergoing chemotherapy. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:53–57. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.6049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonner Millar LP, Casarett D, Vapiwala N, et al. Integrating complementary therapies into an academic cancer center: The perspective of breast cancer patients. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2010;8:106–113. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lengacher CA, Bennett MP, Kip KE, et al. Relief of symptoms, side effects, and psychological distress through use of complementary and alternative medicine in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:97–104. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.97-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Society for Oncology Massage: What is oncology massage? http://www.s4om.org/oncology-massage-overview.

- 21.Bower JE. Behavioral symptoms in patients with breast cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:768–777. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell AJ, Baker-Glenn EA, Granger L, et al. Can the Distress Thermometer be improved by additional mood domains? Part I. Initial validation of the Emotion Thermometers tool. Psychooncology. 2010;19:125–133. doi: 10.1002/pon.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karagozoglu S, Kahve E. Effects of back massage on chemotherapy-related fatigue and anxiety: Supportive care and therapeutic touch in cancer nursing. Appl Nurs Res. 2013;26:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernández-Lao C, Cantarero-Villanueva I, Díaz-Rodríguez L, et al. Attitudes towards massage modify effects of manual therapy in breast cancer survivors: A randomised clinical trial with crossover design. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2012;21:233–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drackley NL, Degnim AC, Jakub JW, et al. Effect of massage therapy for postsurgical mastectomy recipients. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16:121–124. doi: 10.1188/12.CJON.121-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Listing M, Krohn M, Liezmann C, et al. The efficacy of classical massage on stress perception and cortisol following primary treatment of breast cancer. Arch Women Ment Health. 2010;13:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan YQ, Yang KH, Wang YL, et al. Massage interventions and treatment-related side effects of breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Oncol. 2014;19:829–841. doi: 10.1007/s10147-013-0635-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenlee H, Balneaves LG, Carlson LE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines on the use of integrative therapies as supportive care in patients treated for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2014;2014:346–358. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgu041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar P, Casarett D, Corcoran A, et al. Utilization of supportive and palliative care services among oncology outpatients at one academic cancer center: Determinants of use and barriers to access. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:923–930. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Post-White J, Kinney ME, Savik K, et al. Therapeutic massage and healing touch improve symptoms in cancer. Integr Cancer Ther. 2003;2:332–344. doi: 10.1177/1534735403259064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boon H, Brown JB, Gavin A, et al. Breast cancer survivors’ perceptions of complementary/alternative medicine (CAM): Making the decision to use or not to use. Qual Health Res. 1999;9:639–653. doi: 10.1177/104973299129122135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bauml JM, Chokshi S, Schapira MM, et al. Do attitudes and beliefs regarding complementary and alternative medicine impact its use among patients with cancer? A cross-sectional survey. Cancer. 2015;121:2431–2438. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]