Highlights

-

•

Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage caused by pseudoaneurysm following total remnant pancreatectomy is a rare complication.

-

•

Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage should be considered even in the absence of any history of pancreatic fistula and intra-abdominal abscess.

-

•

Gastrointestinal bleeding is necessary to recognize sentinel bleeding if the origin is undetectable.

Abbreviations: PPH, postpancreatectomy hemorrhage; RHA, right hepatic artery; CT, computed tomography; IPMC, intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma; RCCs, red cell concentrates; POD, postoperative day; LHA, left hepatic artery; GIE, gastrointestinal endoscopy; TAE, transcatheter arterial embolization

Keywords: Case report, Pseudoaneurysm, Total remnant pancreatectomy, Pancreatic fistula, Sentinel bleeding

Abstract

Introduction

Pseudoaneurysm is a serious complication after pancreatic surgery, which mainly depends on the presence of a preceding pancreatic fistula. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage following total pancreatectomy is a rare complication due to the absence of a pancreatic fistula. Here we report an unusual case of massive gastrointestinal bleeding due to right hepatic artery (RHA) pseudoaneurysm following total remnant pancreatectomy.

Presentation of case

A 75-year-old man was diagnosed with intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma recurrence following distal pancreatectomy and underwent total remnant pancreatectomy. After discharge, he was readmitted to our hospital with melena because of the diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed to detect the origin of bleeding, but an obvious bleeding point could not be detected. Abdominal computed tomography demonstrated an expansive growth, which indicated RHA pseudoaneurysm. Emergency angiography revealed gastrointestinal bleeding into the jejunum from the ruptured RHA pseudoaneurysm. Transcatheter arterial embolization was performed; subsequently, bleeding was successfully stopped for a short duration. Because of improvements in his general condition, the patient was discharged.

Discussion

To date, very few cases have described postpancreatectomy hemorrhage following total remnant pancreatectomy. We suspect that the aneurysm ruptured into the jejunum, possibly because of the scarring and inflammation associated with his two complex surgeries.

Conclusion

Pseudoaneurysm should be considered when the fragility of blood vessels is suspected, despite no history of anastomotic leak and intra-abdominal abscess. Our case also highlighted that detecting gastrointestinal bleeding is necessary to recognize sentinel bleeding if the origin of bleeding is undetectable.

1. Introduction

Recently, pancreatic surgery has been considered as a complex abdominal surgery, and several improvements in surgical techniques and perioperative care have been distinctly made. Perioperative mortality rate in high-volume centers is 2% [1]. Despite advances in surgical techniques and perioperative care, pancreatic surgery is still associated with a high perioperative morbidity rate of approximately 50% [2]. Specific complications following pancreatic surgery include pancreatic fistula, bile leakage, delayed gastric emptying, and postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH), which results in long-term hospitalization.

PPH is a less common but serious complication with an incidence of 1%–8% in all pancreatic surgeries [3]. Late PPH is a life-threatening complication, which accounts for 11%–38% of the overall mortality. PPH is mainly associated with pancreatic fistula and intra-abdominal abscess [4]. Therefore, the occurrence of PPH is relatively less following total pancreatectomy compared with other pancreatic surgeries with no pancreatic fistula. We recently experienced a patient with massive gastrointestinal bleeding due to right hepatic artery (RHA) pseudoaneurysm following total remnant pancreatectomy, although no signs of pancreatic fistula, bile leak, and intra-abdominal abscess were detected. We successfully treated the patient using emergency coil embolization, which we report here. This report is compliant with the SCARE criteria and PROCESS guidelines published on case report submissions [5], [6].

2. Presentation of case

A 71-year-old man was admitted to a local hospital due to repeated episodes of abdominal pain with high serum amylase levels. He was transferred to our hospital for further examination. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed mixed intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm in the pancreatic body and tail. Distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy were performed to treat the pancreatic tumor. Histopathological examination revealed an intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma (IPMC). He was discharged from our hospital with an uneventful postoperative course. Three and half years after the operation, abdominal CT revealed the dilation of the main pancreatic duct and a cystic lesion in the pancreatic head. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed. Cytological diagnosis of pancreatic juice revealed adenocarcinoma, and he was diagnosed with recurrent IPMC in the remnant pancreas. He underwent total remnant pancreatectomy. Hepatoduodenal ligament skeletonization was also performed to remove neural and lymphatic tissues. Postoperative severe adhesion and fibrosis due to the first operation was seen around the portal vein area. Therefore, blood oozing from dissected peripancreatic tissue and arterial hemorrhage from hepatoduodenal ligament were seen. The procedure took 450 min for completion. The amount of blood loss during the operation was 2528 ml, and 2 units of packed red cell concentrates (RCCs) were transfused. The post-surgery progress was good, and the abdominal drain tube was removed with no sign of anastomotic leak on postoperative day (POD) 6. During hospitalization, he was febrile with elevated white blood cell count, C-reactive protein level, and transaminase levels. CT revealed no remarkable abnormality including intra-abdominal abscess. Therefore, he was diagnosed with postoperative cholangitis and treated with a course of antibiotics. After the cholangitis was controlled, he was discharged from our hospital. After discharge, he had two more episodes of melena and was readmitted because of the diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding. Hemoglobin level on the day of hospital readmission was 5.8 g/dL. Upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy (GIE) revealed blood clotting and ulcers with no active bleeding. He was transfused with 12 units of packed RCCs, and his hemoglobin levels elevated to 7.3 g/dL. On POD 35, melena stopped, and his hemoglobin level did not decrease. Abdominal CT was also performed and demonstrated RHA pseudoaneurysm with a diameter of 8 mm (Fig. 1a). On POD 38, melena was again observed without circulatory disturbance. Abdominal CT revealed that the size of RHA pseudoaneurysm increased to a diameter of 12 mm (Fig. 1b). Subsequently, an emergency abdominal angiography was performed, which demonstrated gastrointestinal bleeding due to RHA pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 2a). During the angiography, he developed shock with hypotension and tachycardia. He was transfused with 10 units of packed RCCs. The patency from the common hepatic artery to left hepatic artery (LHA) was confirmed, and coil embolization for RHA was performed; consequently, his blood pressure immediately normalized and hepatic perfusion from LHA was confirmed (Fig. 2b). He was admitted to the intensive care unit after this procedure. His blood pressure remained stable, and he was moved to a general ward after 3 days. Abdominal CT revealed no extravasation, and he was discharged on POD 51 (Fig. 3). He is now being followed up at our hospital, and no evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding has been observed until his last follow-up visit.

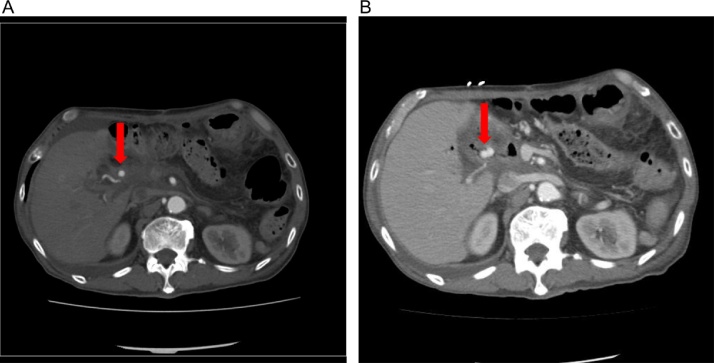

Fig. 1.

Abdominal enhanced computed tomography images.

(A) Computed tomography revealed a right hepatic pseudoaneurysm of 8-mm diameter (arrow) on postoperative day 34.

(B) Computed tomography revealed a right hepatic pseudoaneurysm of 12-mm diameter (arrow) on postoperative day 38.

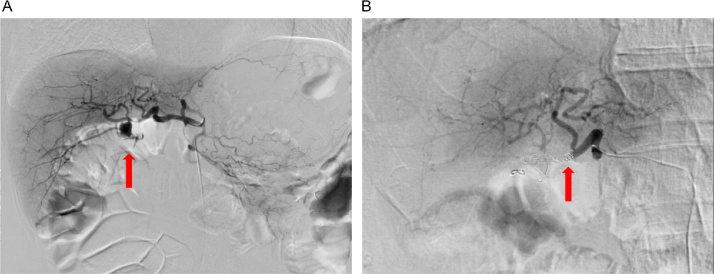

Fig. 2.

Images of findings before and after endovascular treatment of the right hepatic pseudoaneurysm.

(A) Emergency angiogram confirming a pseudoaneurysm emerging from the right hepatic artery to reconstruct the jejunum limb (arrow).

(B) Extravasation disappeared (arrow). Blood flow to the liver via the left hepatic artery was confirmed after coil embolization for the right hepatic artery.

Fig. 3.

Clinical course for postoperative days.

A total of 22 units of packed red cell concentrates were transfused since readmission.

3. Discussion

PPH is one of the most lethal complications after pancreatic surgery. The bleeding site of PPH mostly originates from the arterial vessels, mainly due to pseudoaneurysm emerging from the gastroduodenal artery stump, common hepatic artery or tributaries of the superior mesenteric artery. Pseudoaneurysm formation after pancreatic surgery has been correlated with the presence of pancreatic fistula or intra-abdominal abscess [3], [4], [7]. Generally, the enzymatic digestion of the arterial wall is achieved using trypsin, elastase, and other pancreatic enzymes, which are secondary to the pancreatic fistula. Therefore, PPH due to ruptured pseudoaneurysm is a rare condition after total remnant pancreatectomy because of the lack of pancreatic fistula. Thus far, no case report has described a ruptured pseudoaneurysm after total remnant pancreatectomy. A prospective analysis of 1669 patients undergoing pancreatic resection demonstrated the absence of pseudoaneurysm due to PPH during total pancreatectomy [7]. They also mentioned that PPH prognosis is closely associated with a preceding pancreatic fistula. The present case belongs to grade C PPH due to ruptured pseudoaneurysm according to the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery definition [3], and several reasons for the ruptured pseudoaneurysm were speculated. First, RHA injury during lymphadenectomy might be caused due to severe adhesion and fibrosis. The injury may have caused the formation of pseudoaneurysm. In general, the remnant pancreatectomy may be more difficult than other pancreatic surgeries and lead to higher risk. The surgical dissection of the peripancreatic arterial vessels may cause inapparent arterial wall lesions that mature in the postoperative period. Okuno et al. have reported that a mechanical injury of the artery during operation was mainly due to lymphadenectomy for treating malignancy, which can potentially occur during late PPH [8]. Second, arterial vessels become fragile because of repeated pancreatitis. Although chronic pancreatitis with pseudoaneurysm is rare, Chiang et al. have reported that pancreatic juice leakage due to repeated inflammation results in the erosion of pancreatic or nearby vessels [9]. We observed repeated episodes of abdominal pain with high serum amylase levels before initial distal pancreatectomy, which may have resulted because of chronic pancreatitis. Third, we diagnosed cholangitis at the time of elevated inflammatory response after total remnant pancreatectomy; however, microscopic intra-abdominal abscess, which was not detected by abdominal CT, might have existed. Possibly, microscopic intra-abdominal abscess gradually spread and caused the pseudoaneurysm. Although there was no obvious intra-abdominal abscess, we should have followed it up more carefully.

A pseudoaneurysm may be accompanied with pain, discomfort, or occult bleeding, which is known as sentinel bleeding. Sentinel bleeding is an early warning sign and is defined as a drop in the hemoglobin levels to <1.5 g/dL without hemodynamic instability and followed by another hemorrhagic episode after a symptom-free interval [10]. Recently, it has been observed in approximately 60%–80% of PPH patients [11], [12]. To prevent massive hemorrhage, it is important to adequately manage sentinel bleeding as soon as possible. In early PPH, a small amount of blood in the nasogastric or abdominal drain tube can be easily detected and considered as sentinel bleeding. However, in late PPH, this detection is difficult because of the removal of the nasogastric or abdominal drain tube. In our case, melena was detected, which represents the rupture of RHA pseudoaneurysm, suggesting a communication between RHA pseudoaneurysm and reconstructed jejunum limb. We suspected that melena occurred because of sutured lines of anastomoses or gastric or duodenal ulcers. Therefore, GIE was performed, although the cause of bleeding remained unclear. GIE may be useful in excluding intraluminal bleeding due to ulcers and suture lines. However, if the origin of gastrointestinal bleeding is undetectable, then repeated episodes of melena can be related to sentinel bleeding. In other words, a bleeding pseudoaneurysm in a major visceral artery should be suspected when massive intraluminal bleeding from an unknown origin is encountered, even without any sign of pancreatic fistula and intra-abdominal abscess.

In the case of ruptured pseudoaneurysm, rapid management is required. In such cases, effective therapeutic procedures include endovascular treatment, or immediate laparotomy. However, laparotomy during hemorrhagic shock can have serious complications. Therefore, endovascular treatment such as transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) or stent graft replacement therapy is likely to be the first choice for temporary control of bleeding, and urgent surgery should be limited to when endovascular treatment fails. In comparison with TAE, stent graft replacement therapy is superior in preserving the hepatic perfusion. In the present case, we confirmed the patency from the common hepatic artery to LHA before coil embolization. Therefore, TAE was performed, and we confirmed the hepatic perfusion from LHA. In general, TAE and stent graft replacement therapy are individually given depending on the involved artery and the vascular anatomy. Recently, stent graft replacement therapy for pseudoaneurysm was covered under public medical insurance in Japan; this therapy is supposed to increase in near future.

4. Conclusion

We reported a rare case of gastrointestinal bleeding due to RHA pseudoaneurysm following total remnant pancreatectomy. Late PPH from pseudoaneurysm following total pancreatectomy should be taken into consideration even in the absence of previous anastomotic leak or intra-abdominal abscess. It is recognized that endovascular treatment has a significant role to play in the immediate management of PPH. Our case also highlighted that if the origin of bleeding is undetectable, then gastrointestinal bleeding is necessary to recognize sentinel bleeding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors declare that they have no supportive funding.

Ethical approval

This work does not require a deliberation by the ethics committee. For case report our institute exempted to take ethical approval.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the consent document is available for review by the editor-in-chief of this journal.

Authors contribution

Atsushi Fujio is a major contributor in writing the manuscript. Yohei Ozawa, Kurodo Kamiya, Takanobu Nakamura, Jin Teshima, Kazushige Murakami, On Suzuki, Go Miyata, and Izumi Mochizuki were attending doctors who performed clinical treatment, including surgical operation. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Guarantor

Atsushi Fujio accept full responsibility for the work and had controlled the decision to publish.

Contributor Information

Atsushi Fujio, Email: wisteriatail@med.tohoku.ac.jp, wisteriatail723@gmail.com.

Masahiro Usuda, Email: usumasa69@me.com.

Yohei Ozawa, Email: ozawa.youhei@opal.plala.or.jp.

Kurodo Kamiya, Email: k__claude@hotmail.com.

Takanobu Nakamura, Email: taknakamura@med.tohoku.ac.jp.

Jin Teshima, Email: jintesshy@yahoo.co.jp.

Kazushige Murakami, Email: lanevo@chuo-hp.jp.

On Suzuki, Email: onsuzuki54@gmail.com.

Go Miyata, Email: miyata5@med.tohoku.ac.jp.

Izumi Mochizuki, Email: imochizu@chuo-hp.jp.

References

- 1.Fernandez-del Castillo C., Morales-Oyarvide V., McGrath D., Wargo J.A., Ferrone C.R., Thayer S.P. Evolution of the Whipple procedure at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Surgery. 2012;152:S56–S63. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conzo G., Gambardella C., Tartaglia E., Sciascia V., Mauriello C., Napolitano S. Pancreatic fistula following pancreatoduodenectomy: evaluation of different surgical approaches in the management of pancreatic stump. Literature review. Int. J. Surg. 2015;21(Suppl. 1):S4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.04.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wente M.N., Veit J.A., Bassi C., Dervenis C., Fingerhut A., Gouma D.J. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an international study group of pancreatic surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery. 2007;142:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tien Y.W., Lee P.H., Yang C.Y., Ho M.C., Chiu Y.F. Risk factors of massive bleeding related to pancreatic leak after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2005;201:554–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P. The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Rajmohan S., Barai I., Orgill D.P., Group P. Preferred reporting of case series in surgery; the PROCESS guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;36:319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yekebas E.F., Wolfram L., Cataldegirmen G., Habermann C.R., Bogoevski D., Koenig A.M. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage: diagnosis and treatment: an analysis in 1669 consecutive pancreatic resections. Ann. Surg. 2007;246:269–280. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000262953.77735.db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okuno A., Miyazaki M., Ito H., Ambiru S., Yoshidome H., Shimizu H. Nonsurgical management of ruptured pseudoaneurysm in patients with hepatobiliary pancreatic diseases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1067–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiang K.C., Chen T.H., Hsu J.T. Management of chronic pancreatitis complicated with a bleeding pseudoaneurysm. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16132–16137. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khalsa B.S., Imagawa D.K., Chen J.I., Dermirjian A.N., Yim D.B., Findeiss L.K. Evolution in the treatment of delayed postpancreatectomy hemorrhage: surgery to interventional radiology. Pancreas. 2015;44:953–958. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koukoutsis I., Bellagamba R., Morris-Stiff G., Wickremesekera S., Coldham C., Wigmore S.J. Haemorrhage following pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and the importance of sentinel bleed. Dig. Surg. 2006;23:224–228. doi: 10.1159/000094754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H.G., Heo J.S., Choi S.H., Choi D.W. Management of bleeding from pseudoaneurysms following pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1239–1244. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i10.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]