To the Editor:

In their recent article, de Kock et al.1 re‐analyzed previously published data from a four‐site African study (conducted in Mali, Mozambique, Sudan, and Zambia) that examined the pharmacokinetics of sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine in women during pregnancy and postpartum. Potential confounders not included in the original modeling reduced, but did not eliminate, between‐site differences in pharmacokinetic parameters. For sulfadoxine, there was an overall threefold higher clearance during pregnancy vs. that after delivery, consistent with other available data2, 3, 4 and reflecting pregnancy‐associated physiological changes.1 Pyrimethamine clearance was, by contrast, 18% lower in pregnancy compared with the postpartum period, with a reduced area under the plasma concentration‐time curve (AUC) after delivery.1

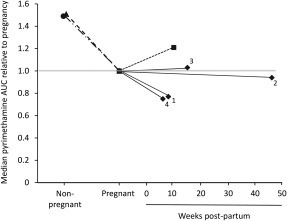

The lower pregnancy‐associated pyrimethamine clearance reported by de Kock et al.1 would be unusual, as there are few drugs that exhibit this property. We recently re‐examined our own published pyrimethamine data from pregnant Papua New Guinean women4 and those of other relevant studies with apparently disparate findings, and proposed that lactation status could help to explain between‐study differences. As we outlined,4 national breastfeeding rates in the various studies were high (≥84%) up to 1 year postpartum at the time. There is evidence (see Supplementary Material) that breast tissue expresses cytochrome P450 (CYP) genes, especially CYP1B1 which codes for a key enzyme involved in the metabolism of pyrimethamine, as identified in vitro using recombinant CYP enzymes. At present, the primary interest in mammary enzymes is related to breast malignancy rather than drug metabolism, but the expression of CYP enzymes can be upregulated during breastfeeding, which may reduce maternal exposure postpartum. It is of interest that in all studies that compared the disposition of pyrimethamine during pregnancy with that after delivery, including the four substudies analyzed by de Kock et al.,1 the AUC did not return to levels in nonpregnant women in the postpartum period despite variability between studies (see Figure 1). This suggests strongly that lactating women are not metabolically equivalent to nonpregnant women in the case of pyrimethamine. The reduced pyrimethamine clearance in pregnancy relative to that postpartum, as reported by de Kock et al.,1 does not, therefore, contradict other studies using nonpregnant women as the comparator group that showed increased pyrimethamine clearance and a lower AUC.3, 4

Figure 1.

Pyrimethamine median area under the plasma concentration‐time curve (AUC) relative to pregnancy (set at 1.0 shown by the gray line) in studies from Mali (1), Mozambique (2), Sudan (3), and Zambia (4) (♦—♦) from the pooled re‐analysis,1 as well as Papua New Guinea (▲– –▲),4, Uganda (• ‐ · · ‐ •),3 and Kenya (▪ ‐ ‐ ▪).2

We conclude that there should be careful selection of an appropriate control group in studies of drug disposition in pregnancy, including consideration of lactation, because the postpartum state may not be equivalent to that in nonpregnant women.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

References

- 1. De Kock, M. et al Pharmacokinetics of sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine for intermittent preventive treatment of malaria during pregnancy and after Delivery. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 6, 430–438 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Green, M.D. et al Pharmacokinetics of sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine in HIV‐infected and uninfected pregnant women in Western Kenya. J. Infect . Dis. 196, 1403–1408 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Odongo, C.O. et al Trimester‐specific population pharmacokinetics and other correlates of variability in sulphadoxine‐pyrimethamine disposition among Ugandan pregnant women. Drugs R. D. 15, 351–362 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Salman, S. et al Optimal antimalarial dose regimens for sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine with or without azithromycin in pregnancy based on population pharmacokinetic modeling. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, e02291–e02316 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information