Abstract

Background:

Percutaneous transesophageal gastro-tubing (PTEG) is a minimally invasive technique to access the gut via an esophagostomy. However, this procedure is not well known and the literature available is still fairly limited. This observational study was conducted to evaluate our experience using this method as an alternative long-term tube feeding procedure when gastrostomy is not suitable.

Methods:

A total of 15 patients (10 males and 5 females) who underwent PTEG at our institution from 2012 to 2016 were observed and analyzed in this study.

Results:

The average age was 80.1 (71–93) years. Underlying conditions that required PTEG were previous gastric resection in 11 patients, left diaphragm disorder in 2 patients, interposing transverse colon between the abdominal wall and anterior gastric wall in 1 patient, and severe gastrostomy site leakage in 1 patient. Tube placement was successful in all patients by approaching the left side of the neck, using a 15 Fr size tube. The mean postoperative length of stay was 22 (8–48) days. Postoperative adverse events included accidental tube dislodgement in three patients, tracheoesophageal fistula in one patient, inferior thyroid artery injury in one patient and thyroid gland mispuncture in one patient. There was no procedure-related mortality nor mortality at 30 days. Eight patients were discharged with some oral intake.

Conclusions:

PTEG is feasible in patients requiring long-term tube feeding for whom gastrostomy is unsuitable. It is an effective long-term tube feeding procedure and should be offered as a more comfortable alternative to nasogastric tubing.

Keywords: enteral nutrition, esophagostomy, percutaneous transesophageal gastro-tubing, tube feeding

Background

Although percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is an established procedure for long-term tube feeding in patients with dysphagia or inadequate oral intake, it may not be feasible in some patients.1 Well-recognized contraindications include severe ascites and advance gastric cancer. A previous gastric resection (total or partial), interposing organs (liver or transverse colon) between the abdominal wall and anterior gastric wall or disorders of the left diaphragm (severe herniation or paralysis) also render some patients who need long-term tube feeding unsuitable for PEG. For these patients, the options available are often nasogastric tubing or laparoscopy (or laparotomy) to achieve percutaneous access to the gut.2

Percutaneous transesophageal gastro-tubing (PTEG) is a minimally invasive technique developed in Japan to access the gut via an esophagostomy.3 This procedure was initially developed for patients with malignant obstruction as an alternative to nasogastric decompression.4–6 Later on, it was also adopted to maintain long-term tube feeding in cases where PEG may be risky or not possible.7,8 However, despite being reported in the US more than 10 years ago, PTEG remains a technique unknown to most surgeons (or gastroenterologists) outside Japan and the available literature regarding this method is still fairly limited.9 The procedure was developed in 1994 and has been receiving coverage from Japan’s National Health Insurance since 2012. This observational study was conducted to investigate the clinical outcomes of PTEG as an alternative long-term tube feeding procedure when gastrostomy is not feasible.

Methods

Patients who underwent PTEG at our hospital between July 2012 and Jun 2016 were enrolled into this study. Baseline characteristics of patients such as age, sex, comorbidities, indications and preoperative biomarkers were recorded. Clinical outcomes of interest such as adverse events, postoperative length of stay, place of discharge, readmission rates and mortality (in-hospital, procedure-related, 30-day and 90-day) were observed. All procedures were performed using the only available commercial PTEG kit (Sumitomo Bakelite Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in an interventional radiology suite with the use of fluoroscopy and ultrasonography. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics review committee of Hiroshima Kyoritsu Hospital. Written, informed consent was obtained from the patients or their legal guardians for the procedure, as well as enrollment into our study. This study was carried out in accordance with Japan’s Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Research (2008) and the Declaration of Helsinki (2013).

The percutaneous transesophageal gastro-tubing procedure

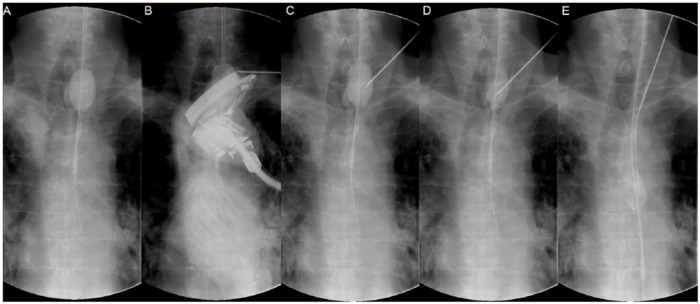

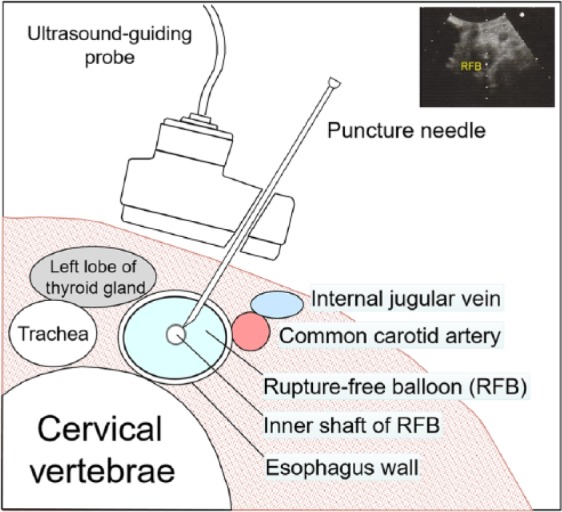

Although this technique has been described previously,3–6 we will go through the various steps in detail, using fluoroscopic images during a PTEG procedure performed on a patient with a previous total gastrectomy (Figures 1 and 2). First, a specially designed rupture-free balloon catheter (14 Fr size, 70 cm length) from the kit was inserted either transnasally or orally under radiological guidance into the upper esophagus just below the thoracic inlet (in this case, with the aid of a guidewire). The rupture-free balloon (RFB) near the tip of the catheter was then inflated with a mixture of distilled water and contrast medium (Figure 1A). Next, the position of the RFB was adjusted between the thoracic inlet and left clavicle so that the ultrasound-guiding probe has direct access to it (Figure 1B). An ultrasound schematic diagram for the optimal puncture position is shown in Figure 3, with an actual ultrasound image on the upper right corner of the figure. Unlike the stomach, the lumen of the esophagus cannot normally be insufflated with air. The RFB has the important role of ‘pseudo-insufflating’ the esophagus so that direct access from the skin surface is possible without compromising the thyroid gland and crucial large blood vessels (Figure 3). Under ultrasonography guidance, the RFB was then punctured with an 18 G puncture needle through the left neck (Figure 1C). Successful puncture was confirmed by the gushing water (and contrast medium) after removing the stylet of the puncture needle. Next, a guidewire was inserted so that the tip of it was retained within the RFB (Figure 1D). The RFB was then advanced along with the guidewire into the lower esophagus (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Fluoroscopic imaging describing the percutaneous transesophageal gastro-tubing procedure on a patient with a previous total gastrectomy (Part 1).

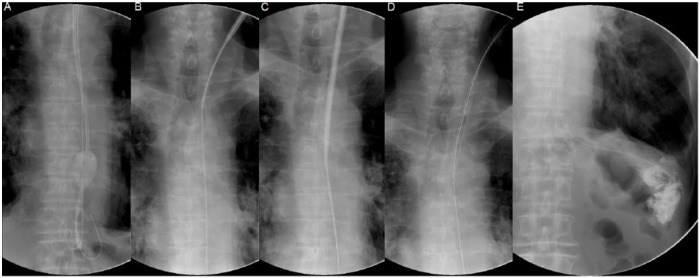

Figure 2.

Fluoroscopic imaging describing the percutaneous transesophageal gastro-tubing procedure on a patient with a previous total gastrectomy (Part 2).

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of ultrasound-guided puncture of the esophagus. (Actual ultrasound image on the upper right corner).

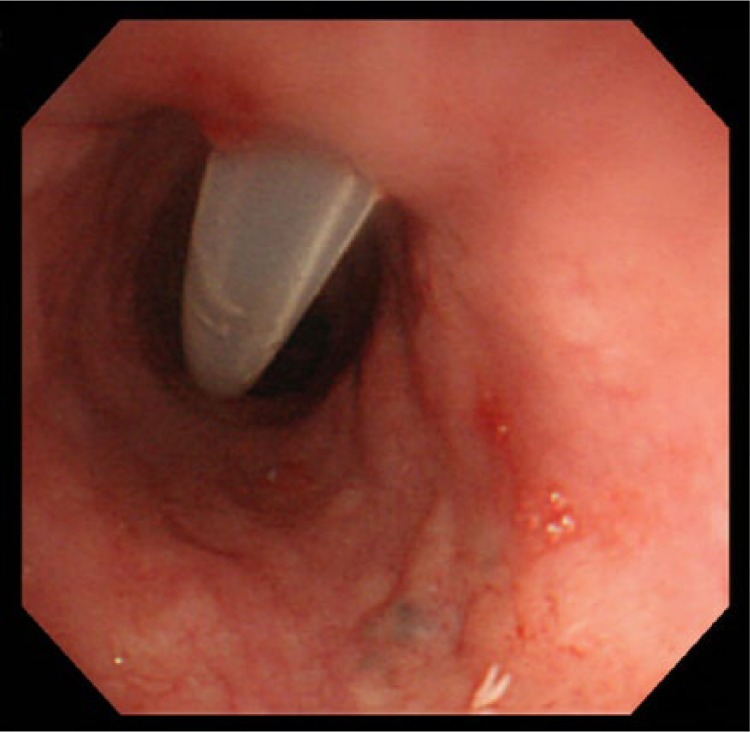

The tip of the guidewire was then dislodged from the RFB (Figure 2A) and after deflation, the RFB catheter was removed to leave only the guidewire in the upper alimentary tract. Next, a 16 Fr size dilator with an 18 Fr size external peel-away sheath was inserted over the guidewire (Figure 2B). After sufficient dilation (Figure 2C), the dilator was removed to leave only the guidewire and the external sheath in place. A 15 Fr size feeding tube (45 cm length) was then inserted over the guidewire via the external sheath (Figure 2D). After removing the guidewire, contrast medium was injected into feeding tube to confirm that the tip of the tube was placed appropriately (Figure 2E). Finally, the external sheath was peeled away and the feeding tube was then secured to the neck at skin level with suture and a specialized collar. A postprocedural endoscopic imaging of the upper esophagus is shown in Figure 4. Local anesthesia and mild conscious sedation with diazepam were used. Enteral feeding resumed the following day.

Figure 4.

Endoscopic imaging of the percutaneous transesophageal gastro-tubing tube after procedure.

Results

A total of 15 patients (10 male and 5 females) who underwent PTEG at our hospital were included in this study. Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of these patients. The average age during tube placement was 80.1 (71–93) years. The majority of patients had impaired oral intake due to a previous stroke, dementia or neurodegenerative disorders. The underlying conditions that required PTEG (indications) were previous gastric resection in 11 patients (5 with total gastrectomy and 6 with partial gastric resection), left diaphragm disorder in 2 patients (one with diaphragm paralysis and the other with severe herniation), interposing transverse colon in 1 patient and severe gastrostomy site leakage in 1 patient. The nutritional status of patients undergoing the procedure was generally poor, with the average body mass index of 16.3 ± 2.5 kg/m2 and serum albumin levels at 2.7 ± 0.5 g/dl.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients.

| Characteristics | (n = 15) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (range) | 80.1 (71–93) |

| Sex, male (M)/female (F) | 10/5 |

| Comorbidities (overlapping): | |

| • Stroke, n (%) | 10 (67) |

| • Dementia, n (%) | 6 (40) |

| • Neurodegenerative disorders, n (%) | 4 (27) |

| • Respiratory disorders, n (%) | 9 (60) |

| Underlying condition requiring PTEG: | |

| • Previous gastric resection, n (%) | 11 (73) |

| • Left diaphragm disorder, n (%) | 2 (13) |

| • Transverse colon obstruction, n (%) | 1 (7) |

| • Severe gastrostomy site leakage, n (%) | 1 (7) |

| Preoperative biomarkers: | |

| • BMI kg/m2, mean (SD) | 16.3 (2.5) |

| • Hemoglobin count g/dl, mean (SD) | 11.2 (1.8) |

| • Platelet count ×104/μl, mean (SD) | 26.7 (8.2) |

| • C-reactive protein mg/dl, mean (SD) | 2.5 (3.8) |

| • Serum albumin g/dl, mean (SD) | 2.7 (0.5) |

| • Cholinesterase IU/l, mean (SD) | 145 (34) |

| • Free plasma glucose mg/dl, mean (SD) | 107 (29) |

| • PT-INR, mean (SD) | 1.21 (0.16) |

SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; PT-INR, international normalized ratio of prothrombin time; PTEG, percutaneous transesophageal gastro-tubing.

Clinical outcomes of interest after PTEG procedure are shown in Table 2. The average postoperative length of stay was 22 (8–48) days. Adverse events included accidental tube dislodgement in three patients, tracheoesophageal fistula in one patient, pseudoaneurysm resulting from the injury of the left inferior thyroid artery in one patient and mispuncture of the left lobe of the thyroid glands in one patient. Tube reinsertion through the matured esophagostomy tract in the three patients with accidental tube dislodgement was relatively simple but required confirmation using fluoroscopy. One patient (Table 3, case 6) developed tracheoesophageal fistula due to the mispuncture of the trachea during the procedure. The presence of the feeding tube within the esophagus affected the closure of the fistula and the PTEG tube had to be removed. He went through the procedure again 2 weeks later to insert a new tube. The patient who developed pseudoaneurysm due to an injured left inferior thyroid artery (Table 3, case 12) required interventional radiological treatment using endovascular coiling for hemostasis. The patient with a mispuncture of the thyroid gland (Table 3, case 15) suffered only minor bleeding, requiring neither specialized intervention nor blood transfusion.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes after percutaneous transesophageal gastro-tubing procedure.

| Postoperative length of stay, days, mean (range) | 22 (8–48) |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 1 (7) |

| Procedure-related mortality, n (%) | 0 (0) |

| 30-day mortality, n (%) | 0 (0) |

| 90-day mortality, n (%) | 3 (20) |

| Discharged with some oral intake, n (%) | 8 (53) |

| 30-day readmission after discharge, n (%) | 0 (0) |

| Adverse events: | |

| Accidental tube dislodgement, n (%) | 3 (20) |

| Tracheoesophageal fistula, n (%) | 1 (7) |

| Inferior thyroid artery injury, n (%) | 1 (7) |

| Thyroid gland mispuncture, n (%) | 1 (7) |

| Place of discharge: | |

| Home, n (%) | 4 (27) |

| Nursing institution, n (%) | 3 (20) |

| Long-term care hospital, n (%) | 7 (47) |

Table 3.

List of patients who received percutaneous transesophageal gastro-tubing procedure.

| Case | Sex/age (y) | Underlying condition | Tube used | Approach | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F/89 | Antrectomy (Billroth II) | 15 Fr 45 cm button | Left side | Discharged |

| 2 | M/78 | Colon obstruction | 15 Fr 45 cm button | Left side | Discharged |

| 3 | M/71 | Total gastrectomy | 15 Fr 45 cm button | Left side | Discharged |

| 4 | M/86 | Antrectomy (Billroth I) | 15 Fr 45 cm button | Left side | Discharged |

| 5 | M/74 | Total gastrectomy | 15 Fr 45 cm button | Left side | Died |

| 6 | M/83 | Antrectomy (Billroth II) | 15 Fr 45 cm button | Left side | Discharged |

| 7 | F/77 | Diaphragm paralysis | 15 Fr 45 cm button | Left side | Discharged |

| 8 | F/72 | Diaphragm herniation | 15 Fr 45 cm button | Left side | Discharged |

| 9 | F/93 | Total gastrectomy | 15 Fr 45 cm button | Left side | Discharged |

| 10 | M/85 | Antrectomy (Billroth II) | 15 Fr 45 cm button | Left side | Discharged |

| 11 | M/82 | Antrectomy (Billroth I) | 15 Fr 45 cm button | Left side | Discharged |

| 12 | M/80 | Total gastrectomy | 15 Fr 45 cm button | Left side | Discharged |

| 13 | M/74 | Antrectomy (Billroth II) | 15 Fr 45 cm button | Left side | Discharged |

| 14 | M/84 | Total gastrectomy | 15 Fr 45 cm button | Left side | Discharged |

| 15 | F/74 | Peristomal leakage | 15 Fr 45 cm button | Left side | Discharged |

There was no procedure-related mortality and only one in-hospital mortality due to the patient’s comorbidity (respiratory disorder). There was no mortality at 30 days postoperatively but three patients (20%) died before the 90-day mark. Eight (>50%) patients were discharged with some degree of oral intake and three patients resumed full oral intake, with one of them opting for the removal of the PTEG tube after discharge. Seven patients were discharged to either their homes or nursing institutions, while the remaining were sent to long-term care hospitals. There were no emergency readmissions within 30 days of discharge. Table 3 provides a summarized list of the patients who received PTEG at our hospital during the study period. After discharge, regular tube replacement was performed every 2–3 months as a follow up and to prevent tube dysfunction.

Discussion

For patients with dysphagia or impaired oral intake, tube feeding is often needed to maintain sufficient enteral nutrition. Although tube feeding can be initiated using nasogastric (or nasojejunal) tubes, percutaneous routes are usually preferable for the long-term. Gastrostomy by PEG has long been recognized as the standard percutaneous tube feeding route because it is generally safe and effective.1 However, PEG may be contraindicated in patients with severe ascites, partial gastrectomy, advanced gastric cancer involving the anterior wall of the stomach and intra-abdominal metastasis. PEG is also not suitable in patients with total gastrectomy, interposing organs (liver or transverse colon) between the abdominal wall and anterior gastric wall, and severe left diaphragm disorders where the stomach is displaced within the thoracic cage.8 PEG procedure on these patients may result in organ injury and other life-threatening adverse events.10

When percutaneous access to the stomach via PEG is not feasible, accessing the small intestine (usually jejunum) using direct percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy (D-PEJ) is an option that can be considered.11 This is provided there are no other abdominal contraindications, such as severe ascites and intra-abdominal metastasis. However, D-PEJ is not as simple as PEG and the procedure may be technically impossible in up to 38% of patients.12 Prolonged jejunal feeding has been associated with adverse events such as copper deficiency and late dumping syndrome.13,14 Peristomal leakage rate for D-PEJ has also been reported to be higher than PEG and may impede continuous enteral nutrition.15,16

In 1994, PTEG was developed by Oishi et al. in Japan as a minimally invasive technique to access the gut via an esophagostomy.3 This procedure was initially developed for gastrointestinal decompression in patients with malignant obstruction but is also used as an alternative method to achieve percutaneous tube feeding when PEG is unsuitable or risky. Unfortunately, PTEG remains a technique unknown to most surgeons and gastroenterologists outside of Japan. Recognizing its utility, Japan’s National Health Insurance began providing coverage for this procedure in 2012. Patients included in our study were recruited after coverage began.

Our experience showed that PTEG was a relatively safe and very effective procedure for long-term tube feeding in patients with impaired oral intake. Due to the minimally invasive nature of this technique, it was well tolerated even in patients with poor general status, as shown in Table 1. Nevertheless, we did encounter two major adverse events requiring interventions described in the results section. In patients with adverse events, the esophagostomy tract was compromised in one patient (Table 3, case 6), requiring a repeat of the procedure. The postoperative mortality rates of PTEG in our study were also low, with only three deaths occurring within the first 90 days following the procedure and all of them due to pre-existing comorbidities.

Although PTEG is performed on the neck of the patient below the level of the thoracic inlet, swallowing function does not seem to be affected, as more than 50% of patients were discharged with some oral intake. Three patients even regained full oral intake after dysphagia therapy at our rehabilitation ward. It should also be noted that cases 7 and 15 from Table 3 were patients with a tracheostomy tube in place before receiving the PTEG procedure. In our experience, an existing tracheostomy tube did not influence the procedure itself, nor did it have any negative effect on the postoperative clinical course of patients.

This procedure is usually executed with the use of ultrasonography combined with fluoroscopy but can also be performed using ultrasonography with endoscopic assistance.17 Apart from overcoming some of the contraindications of PEG and possible adverse events from D-PEJ, PTEG may also offer some advantages over standard gastrostomy tube feeding. First of all, because the puncture site (esophagostomy site) is relatively distant from the tip of the inserted feeding tube, it is possible to start enteral feeding immediately after the procedure. Secondly, normal gastric peristalsis may not be affected in patients with PTEG, unlike in patients with PEG, where the stomach becomes fixed to the abdominal wall because of the feeding tube. Cervical pharyngostomy is a surgical procedure that achieves similar results.18 However, it usually requires general anesthesia and the percutaneously inserted tube passes through the hypopharynx into the esophagus, which may still cause some discomfort (but less than nasogastric tubing) as a long-term alternative. Although this study may be limited by its small size, we hope our experience with PTEG described here will be of use to healthcare professionals specializing in the field of enteral nutrition.

Conclusions

Esophagostomy via PTEG is a feasible procedure for patients requiring long-term tube feeding but are not suitable candidates for gastrostomy tube placement. It is effective as an alternative long-term tube feeding procedure and should be offered to patients as a more comfortable option instead of relying on nasogastric tubing alone. Since enteral nutrition is largely recognized as the route of choice when gut integrity is intact, PTEG is an alternative worth exploring when PEG is not possible.

Acknowledgments

EWTY designed and performed the study, managed the data and drafted the manuscript. EWTY and KN participated in the procedures described in the study. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. The authors contributed equally to this work.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Ezekiel Wong Toh Yoon, Department of Internal Medicine, Hiroshima Kyoritsu Hospital, 2-20-20 Nakasu Asaminami-ku, Hiroshima City, Japan.

Kazuki Nishihara, Department of Internal Medicine, Hiroshima Kyoritsu Hospital, Hiroshima City, Japan.

References

- 1. Gauderer MW, Ponsky JL, Izant RJ., Jr. Gastrostomy without laparotomy: a percutaneous endoscopic technique. J Pediatr Surg 1980; 15: 872–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Edelman DS, Unger SW. Laparoscopic gastrostomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1991; 173: 401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oishi H, Shindo H, Shirotani N, et al. A nonsurgical technique to create an esophagostomy for difficult cases of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Surg Endosc 2003; 17: 1224–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Udomsawaengsup S, Brethauer S, Kroh M, et al. Percutaneous transesophageal gastrostomy (PTEG): a safe and effective technique for gastrointestinal decompression in malignant obstruction and massive ascites. Surg Endosc 2008; 22: 2314–2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Singal AK, Dekovich AA, Tam AL, et al. Percutaneous transesophageal gastrostomy tube placement: an alternative to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in patients with intra-abdominal metastasis. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 71: 402–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aramaki T, Arai Y, Inaba Y, et al. Phase II study of percutaneous transesophageal gastrotubing for patients with malignant gastrointestinal obstruction; JIVROSG-0205. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013; 24: 1011–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yamamoto T, Enomoto T, Matsumura A. Percutaneous transesophageal gastrotubing: alternative tube nutrition for a patient with a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Surg Neurol 2009; 72: 278–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Toh Yoon EW. Esophagostomy for percutaneous tube feeding in diaphragm paralysis. Clin Case Rep 2016; 26: 305–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mackey R, Chand B, Oishi H, et al. Percutaneous transesophageal gastrostomy tube for decompression of malignant obstruction: report of the first case and our series in the US. J Am Coll Surg 2005; 201: 695–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Toh Yoon EW, Nishihara K. Liver mispuncture during percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in a patient with a partial gastrectomy. Endoscopy 2016; 48(Suppl. 1): E182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shike M, Schroy P, Ritchie MA, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy in cancer patients with previous gastric resection. Gastrointest Endosc 1987; 33: 372–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maple JT, Petersen BT, Baron TH, et al. Direct percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy: outcomes in 307 consecutive attempts. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100: 2681–2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nishiwaki S, Iwashita M, Goto N, et al. Predominant copper deficiency during prolonged enteral nutrition through a jejunostomy tube compared to that through a gastrostomy tube. Clin Nutr 2011; 30: 585–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Toh Yoon EW, Hisaaki M. Management of postprandial hypoglycemia due to late dumping syndrome after direct percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy (D-PEJ) with miglitol and an isomaltulose-containing enteral formula. Gen Int Med Clin Innov 2016; 1: 86–89. DOI: 10.15761/GIMCI.1000126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim CY, Engstrom BI, Horvath JJ, et al. Comparison of primary jejunostomy tubes versus gastrojejunostomy tubes for percutaneous enteral nutrition. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013; 24: 1845–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Toh Yoon EW, Kaori Y, Shinya N, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic transgastric jejunostomy (PEG-J): a retrospective analysis on its utility in maintaining enteral nutrition after unsuccessful gastric feeding. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2016; 3: e000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Murakami M, Nishino K, Takaoka Y, et al. Endoscopically assisted percutaneous transesophageal gastrotubing: a retrospective pilot study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 25: 989–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kent MS, Awais O, Schuchert MJ, et al. Cervical pharyngostomy: an old technique revisited. Ann Surg 2008; 248: 199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]