Abstract

CHARGE syndrome is a genetic disorder with multi-systemic congenital anomalies, most commonly including coloboma, heart malformations, choanal atresia, developmental delay, and genital and ear anomalies. The diagnostic criteria for CHARGE syndrome has been refined over the years. However, there are limited reports describing skullbase and craniocervical junction abnormalities. These osseous malformations are often under recognized, especially on MRI. We report here a case of CHARGE syndrome with colobomas, cleft lip and palate, patent ductus arteriosus, undescended testes, and a coronal clival cleft which has not been previously depicted in CHARGE syndrome. The presence of a coronal clival cleft should alert the radiologist to examine the ears, eyes, palate, choana, and olfactory centers for other signs of CHARGE syndrome.

Keywords: CHARGE syndrome, coloboma, clival cleft, semicircular canal, Cornelia de Lange syndrome (CdLS)

Introduction

CHARGE syndrome is a rare disorder with multi-systemic congenital anomalies.1 Its prevalence was determined by the Canadian Pediatric Surveillance Program to be 1/8500 live births.2 The acronym ‘CHARGE’ includes: Coloboma, Heart Malformations, Choanal Atresia, Growth and/or developmental Retardations, Genital anomalies and Ear anomalies.2 Since its original description by Hall,3 several studies have refined the diagnostic criteria of CHARGE syndrome to include several major and minor malformations affecting the eyes, ears, pharynx, cranial nerves, and extra-neural tissues.4-6 Herein, we report the first coronal clival cleft in a patient with CHARGE syndrome and other associated anomalies.

Case presentation

A 6 lb, 73-day-old male infant was born by normal vaginal delivery at 37 weeks gestational age. He was born with a feeding and breathing difficulties that required NICU admission for 2 months, gastrostomy tube placement, a cleft lip and palate (diagnosed prenatally), and dysmorphic features. Ophthalmological examination showed coloboma of the iris, choroid and retina of both eyes with macular and optic nerve involvement indicating a guarded visual prognosis. Cardiology and echocardiogram evaluation showed a large patent ductus arteriosus, moderate dilatation of the left atrium and ventricle with mitral regurgitation and patent foramen ovale. Persistent ductus arteriosus ligation was performed at the age of 2 months. The patient failed the newborn hearing screen. Bilateral narrowing of the ear canals, absent tympanic membranes, middle ear pathology and distorted otoacoustic emission testing were noted on audiologic evaluation. Cortical irritability was evident on EEG. Urology evaluation showed undescended testes and micropenis. Molecular and chromosomal analysis revealed CHD7-related CHARGE syndrome with a pathogenic heterozygous mutation in CHD7 gene.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed labyrinthine dysplasia. The cochleas were hypoplastic/dysplastic bilaterally (Figure 1). The semicircular canals were markedly hypoplastic with aplasia of the lateral semicircular canals (Figure 1). The internal auditory canals were small in caliber. Cochlear apertures were aplastic or markedly stenotic. Cochlear nerves were not detectable on either side. No vestibular aqueduct enlargement was present. Olfactory bulbs and tracts were markedly hypoplastic (Figure 2). The globes were dysmorphic with shallow anterior segments and a small coloboma near the right optic nerve head (Figure 3). Bilateral cleft lip and palate was present (Figure 2). A coronal cleft was noted in the basiocciput (Figures 4 and 5). Brain parenchyma showed mild diffuse ventriculomegally, thinning of the corpus callosum, cerebellar vermian and brainstem hypoplasia (Figure 4).

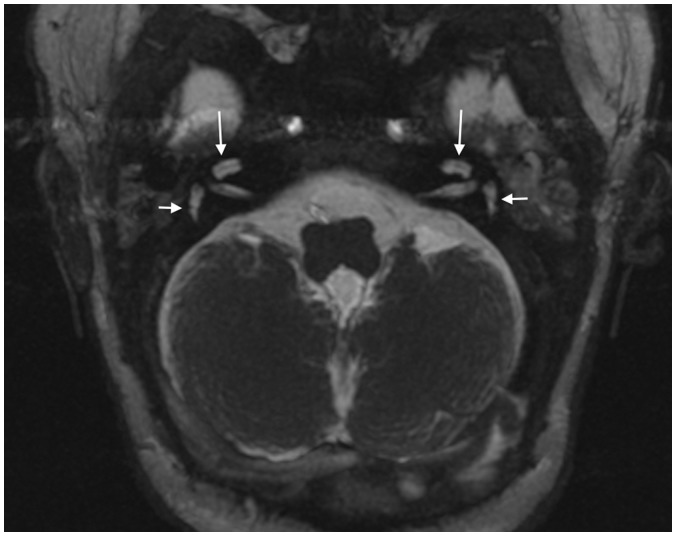

Figure 1.

Axial fast imaging employing steady state acquisition (FIESTA) T2-W through out the internal auditory canals (3-T; TR/TE = 6/2.5 ms, slice thickness = 0.8 mm, slice spacing = 0.4 mm) of 73-day-old boy with CHARGE syndrome shows bilateral cochlear hypoplasia (large arrows), bilateral semicircular canals hypoplasia (small arrows) and internal auditory canal stenosis.

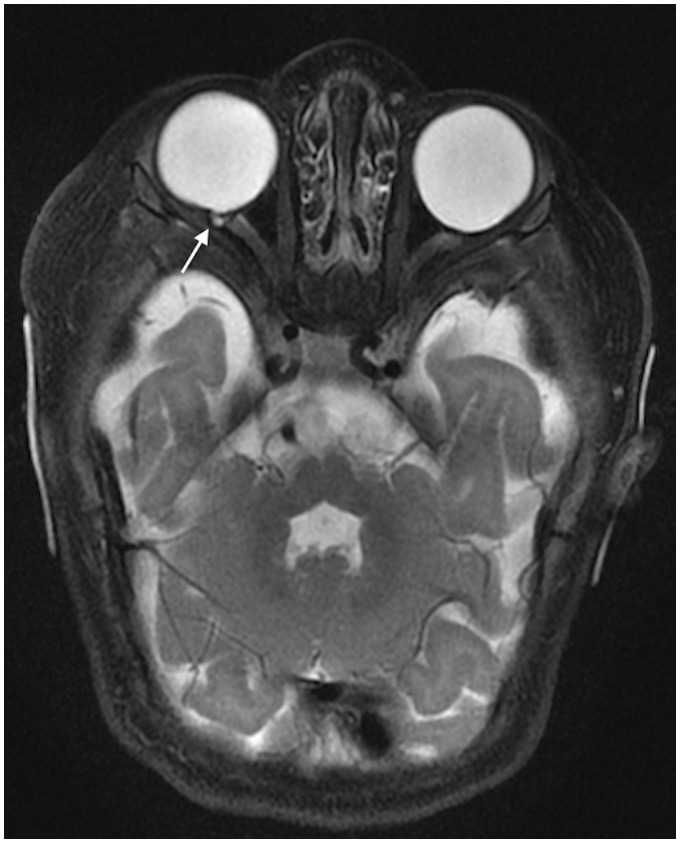

Figure 2.

Coronal fast relaxation fast spin echo acquisition (FRFSE) T2-W with fat suppression image (3-T; TR/TE = 3275/103 ms, slice thickness = 4 mm, slice spacing = 4 mm) of 73-day-old boy with CHARGE syndrome shows bilateral olfactory bulbs hypoplasia (large arrows) with cleft lip and palate (small arrow).

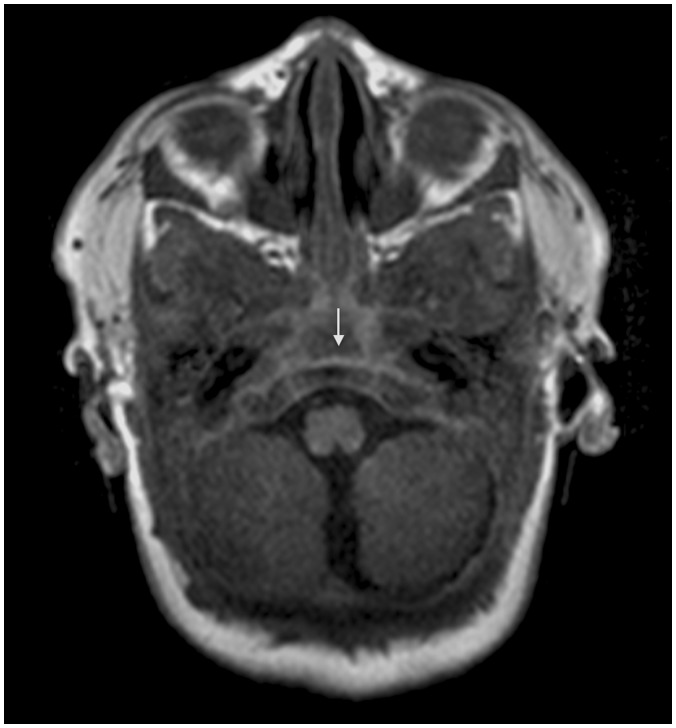

Figure 3.

Axial fast relaxation fast spin echo acquisition (FRFSE) T2-W with fat suppression (3-T; TR/TE = 3200/103 ms, slice thickness = 3.5 mm, slice spacing = 3.5 mm) of 73-day-old boy with CHARGE syndrome shows small right eye coloboma near the optic nerve head (arrow) and deformation of the ocular globes bilaterally. The brainstem is hypoplastic.

Figure 4.

Midline sagittal spoiled gradient recall acquisition (SPGR) T1-W (3-T MR; TR/TE = 7/2.5 ms, IT = 450 ms; slice thickness = 2 mm) of 73-day-old boy with CHARGE syndrome shows thinning of the corpus callosum (small arrow), cerebellar vermian hypoplasia and brainstem volume loss. A distinctive coronally oriented clival cleft in the basioccipit is noted (large arrow).

Figure 5.

Axial spoiled gradient recall acquisition (SPGR) T1-W (3-T MR; TR/TE = 7/2.5 ms, IT = 450 ms; slice thickness = 2 mm) of 73-day-old boy with CHARGE syndrome shows a coronally oriented cleft traversing the clivus (arrow).

Discussion

CHARGE syndrome was first described by Hall in 17 children with choanal atresia and multiple anomalies such as mental retardation, hypogonadism, small ears, cardiac defects, micrognathia, and ocular coloboma.7 On the other hand, Hittner et al. described a syndrome of colobomatous microphthalmia, heart disease, external ear abnormalities with hearing loss and mental retardation in 10 individuals at the same year of 1979.8 Later in 1981, Pagon et al. reported the same findings in 21 patients and introduced the term CHARGE association (which represents C for coloboma, H for heart disease, A for atresia choanae, R for retarded growth and retarded development and/or CNS anomalies, G for genital hypoplasia, and E for ear anomalies and/or deafness).9 With further advancing time and experience with CHARGE association, Blake et al. defined a recognizable CHARGE syndrome with specific diagnostic criteria.5 This was further updated by Verloes to include three major criteria (coloboma, atresia of the choanae, and semicircular canal hypoplasia) and five minor criteria.4

By reviewing the embryogenic development, it appears that all CHARGE’s malformations have occurred during the early first trimester.6 Mutation in CHD7 gene has been reported in 64% of CHARGE patients.10 Molecular genetic analysis for CHD7 gene mutation was positive in our case.

Eye malformations are detectable in up to 80% of CHARGE syndrome, most often coloboma.6 Visual changes are variable; vision ranges from normal vision to severe impairment, depending on the severity of the ocular malformation. In our case, the patient had bilateral coloboma of the iris, choroid, and retina, with macular and optic nerve involvement and resulting guarded visual prognosis.

Choanal atresia is an infrequent developmental anomaly which can be unilateral or bilateral, membranous or bony narrowing of the posterior choana.1,6 It is reported in 35–65% of CHARGE cases. Although our patient did not have choanal atresia, a cleft lip and palate was present, which occurs instead of choanal atresia on occasion in patients with CHARGE.6 Indeed, orofascial defects are detected in 15–20% of patients with CHARGE syndrome.11

Ear anomalies are reported in 80–100% of cases of CHARGE syndrome, with external ear dysmorpholgy being a classical finding in CHARGE syndrome. Hearing abnormities may be either conductive or sensorineural in origin. Distinctive malformations mostly include hypoplastic incus, decreased numbers of cochlear turns, and absent semicircular canals.6,12 Our patient failed the newborn hearing screening test in both ears, and had bilateral ear canal narrowing and middle ear pathology on examination. He also had bilateral cochlear and semicircular canal hypoplasia on MRI.

Olfactory anomalies are one of the highly prevalent anomalies in CHARGE syndrome, reported in up to 100% of cases. They include unilateral or bilateral absence or hypoplasia of the olfactory bulbs or sulci.6,13 Our patient had bilateral olfactory bulb hypoplasia.

Congenital heart defects have been reported in 75–80% of patients with CHARGE syndrome. The most common anomalies are tetralogy of Fallot, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), double outlet right ventricle, atrioventricular canal, ventricular septal defect, and atrial septal defect.6 Our case has a PDA which was ligated at the age of 2 months.

Genito-urinary problems have been reported in CHARGE syndrome, such as penile agenesis, hypospadias, cryptorchidism, bifid scrotum, atresia of uterus, cervix and vagina, solitary kidney, hydronephrosis, renal hypoplasia, duplex kidneys, and vesicoureteral reflux.6 Our patient has undescended testes and micropenis, with no detected renal abnormalities by ultrasound.

Osseous abnormalities are common in CHARGE syndrome, especially at the craniocervical junction. Fujita and colleagues demonstrated a high prevalence of basioccipital hypoplasia and basilar invagination and suggested that these anomalies could be added as new diagnostic criteria.13 Natung et al. reported a case of basilar invagination, short clivus, fused cervical vertebrae, and occipitalization of the atlas.1 Our case is the first depiction of a coronal clival cleft in CHARGE syndrome. We recently described similar clival clefting in a series of patients with Cornelia de Lange syndrome (CdLS).14 Overlapping imaging features of Cornelia de Lange and CHARGE syndrome are brain underdevelopment, labyrinthine dysplasia, globe malformations, and osseous abnormalities including skull base dysplasia and spinal segmentation anomalies.

However, CdLS and CHARGE syndrome are generally well distinguished from one another on physical exam; patients with CdLS manifest distinct facial features and dwarfism.14 Although the etiology of coronal clival clefts is unknown, they likely originate in the first trimester concurrent with other associated CHARGE malformations. These clefts may be due to incomplete fusion of clival ossification centers or enlarged clival canals (fossa navicularis).15

Conclusion

Osseous anomalies are often under recognized in CHARGE syndrome. The craniocervical junction and skullbase should be carefully scrutinized for these characteristic anomalies. The presence of a coronal clival cleft should alert the radiologist to examine the ears, eyes, palate, choana, and olfactory centers for other signs of CHARGE syndrome.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Natung T, Goyal A, Handique A, et al. Symmetrical chorioretinal colobomata with craniovertebral junction anomalies in CHARGE Syndrome - A case report with review of literature. J Clin Imaging Sci 2014; 4(1): 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Issekutz KA, Graham JM, Prasad C, et al. An epidemiological analysis of CHARGE syndrome: Preliminary results from a Canadian study. Am J Med Genet A 2005; 133A(3): 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall BD. Choanal atresia and associated multiple anomalies. J Pediatr 1979; 95(3): 395–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verloes A. Updated diagnostic criteria for CHARGE syndrome: A proposal. Am J Med Genet 2005; 133 A(3): 306–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blake KD, Davenport SL, Hall BD, et al. CHARGE association: An update and review for the primary pediatrician. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1998; 37(3): 159–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Athapaththu AMMK, Koswatta NM. CHARGE syndrome. Sri Lanka J Child Health 2013; 42(2): 101–102. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duncan NO, Miller RH, Catlin FI. Choanal atresia and associated anomalies: The CHARGE association. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1988; 15(2): 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hittner HM, Hirsch NJ, Kreh GM, et al. Colobomatous microphthalmia, heart disease, hearing loss, and mental retardation – a syndrome. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1979; 16(2): 122–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pagon RA, Graham JM, Zonana J, et al. Coloboma, congenital heart disease, and choanal atresia with multiple anomalies: CHARGE association. J Pediatr 1981; 99(2): 223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jongmans MCJ, Admiraal RJ, van der Donk KP, et al. CHARGE syndrome: The phenotypic spectrum of mutations in the CHD7 gene. J Med Genet 2006; 43(4): 306–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lalani SR, Hefner MA, Belmont JW, et al. CHARGE Syndrome. GeneReviews - NCBI Bookshelf 2016, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morimoto AK, Wiggins RH, Hudgins PA, et al. Absent semicircular canals in CHARGE syndrome: Radiologic spectrum of findings. Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27(8): 1663–1671. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujita K, Aida N, Asakura Y, et al. Abnormal basiocciput development in CHARGE syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol 2009; 30(3): 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitehead MT, Nagaraj UD, Pearl PL. Neuroimaging features of Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Pediatr Radiol 2015; 45(8): 1198–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inal M, Muluk NB, Ozveren MF, et al. The presence of Clival foramen through multidetector computed tomography of the skull base. J Craniofac Surg 2015; 26(7): e580–e582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]