Abstract

Public health law has roots in both law and science. For more than a century, lawyers have helped develop and implement health laws; over the past 50 years, scientific evaluation of the health effects of laws and legal practices has achieved high levels of rigor and influence. We describe an emerging model of public health law that unites these two traditions. This transdisciplinary model adds scientific practices to the lawyerly functions of normative and doctrinal research, counseling, and representation. These practices include policy surveillance and empirical public health law research on the efficacy of legal interventions and the impact of laws and legal practices on health and health system operation. A transdisciplinary model of public health law, melding its legal and scientific facets, can help break down enduring cultural, disciplinary, and resource barriers that have prevented the full recognition and optimal role of law in public health.

Keywords: policy surveillance, legal epidemiology, public health practice, public health law, public health law research

INTRODUCTION

For more than a century, public health lawyers have offered legal expertise to public health practitioners. Model statutes (27), treatises (33), and expert reports (42–44) attest to law’s place as an important component of legal academia (4), public health training (22), and public health practice (44). The results of this collaboration have been impressive: Every item on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) list of great public health achievements of the twentieth century can be attributed in part to legal interventions (19). Despite its modern renaissance, the general understanding of public health law has not changed much in the past century. Writing about the field, modern public health lawyers sound like their grandparents. Their definitions of the field center on the application of legal expertise to define the authority of health agencies and to analyze the legal issues that arise when that authority is applied in particular cases. Grounded in legal doctrine and theory, this model includes building and applying normative frameworks, providing representation in legal matters, and translating legal expertise into actionable knowledge to guide both lawyers and nonlawyers in policy development, implementation, and advocacy.

Meanwhile, another facet of public health law was evolving in empirical research. As law became an important tool for public health in the modern regulatory state, scientific researchers began to evaluate its impact in areas such as traffic safety, gun violence, and tobacco control (13). These researchers, and even the lawyers they worked with, did not necessarily think of their work as “public health law.” Rather, they considered it scientific research about the impact of specific legal interventions on health. Although some self-identified public health lawyers participated in scientific evaluations (78, 82), and both the CDC and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded such work, little was done to explicitly link the legal and scientific expressions of public health law or to build an infrastructure for scientific legal research.

Although the CDC’s Public Health Law Program (PHLP) had funded some legal evaluation work after its launch in 2000, a systematic effort to bring legal evaluation research within a public health law framework began only in 2009, when the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) created the Public Health Law Research (PHLR) program (12). The PHLR program’s mission was to build a distinct identity and promote rigorous standards for the scientific study of how laws and legal practices affect public health (18). Through funding, methods support, and intellectual leadership to define the field, the program aimed to unite researchers studying law across different disciplines and public health topics. The impetus was increased by the renewal of the CDC’s PHLP to strengthen the national public health law community and the scientific basis of its work. RWJF’s investment included convening an Institute of Medicine (IOM) panel in 2010 to consider the state of public health law (44), creating the Network for Public Health Law to provide legal technical assistance, launching the Preemption and Movement Building in Public Health project (64), and funding the work of ChangeLab Solutions and the Public Health Law Center to support community-based public health efforts nationwide. RWJF helped developed human capital in public health law through fellowship programs for lawyers working for Attorneys General (http://www.naag.org/publications/papers-briefs-and-other-research/nagtrirobert-woodjohnson-foundation-public-health-law-fellowship-papers.php), law professors (http://clhs.law.gsu.edu/faculty-staff/faculty-fellowship/), and policy-building teams of state health officials (http://www.aspeninstitute.org/policy-work/justice-society/esphl).

The result is a broader, more nuanced understanding of public health law. This understanding, however, is still not widely shared or accepted in either public health or law. Failure to integrate law and public health creates unavoidable gaps in policy and in the translation of evidence into widely deployed legal interventions and reforms. To encourage adoption of this new, enhanced concept of public health law, we present here a transdisciplinary model of public health law, bringing together the legal and scientific traditions within a truly integrated field with two intertwined branches: “public health law practice” and “legal epidemiology.” We describe these branches and then apply the model to define needs and priorities more clearly and to set out a course of practical changes that will help achieve the elusive goal that public health law has long articulated: widespread recognition as a distinct and essential discipline of public health (31, 67).

PUBLIC HEALTH LAW PRACTICE

Public health law has been a distinct field of law for more than a century. A seminal document in the development of public health practice in America, Shattuck’s (70) Report of A General Plan for the Promotion of General and Public Health, made the case for health legislation. Along with important treatises on the police power (28, 79), books devoted solely to public health law were written as early as 1892 (6, 60). Tobey maintained a treatise through the 1930s (80), and articles providing an overview of public health legal authority appeared in public health journals every decade or so (39, 48, 55). In the 1950s, the Public Health Law Research Project at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law proposed revisions to hospital, vital statistics and disease prevention and control, and local health administration laws, at least some of which were adopted (72). Frank Grad (36) published the first edition of his Public Health Law Manual in 1965 and produced new editions for 40 years (35). The 2000s saw Lawrence Gostin’s influential treatise as well as important works by public health law experts such as Wendy Parmet (61) and Richard Goodman and colleagues (30).

The contention that public health law should be considered a distinct legal field, like constitutional law or environmental law, did not go unchallenged (4). Some leading scholars also contested the broad scope of the field, urging that public health law should confine itself to traditional legal issues related to disease and injury control and stay away from broad social and environmental interventions targeting lifestyle risks and structural social dysfunctions (26, 69). No one, however, questioned that, at its core, public health law is a branch of legal practice, the responsibility primarily of lawyers. In 1961, Hamlin (39) defined public health law as “the application of general legal principles to the practice of public health” (p. 1733). Thirty years later, Gostin (33) offered more nuance but the same view:

Public health law is the study of the legal powers and duties of the state to assure the conditions for people to be healthy (e.g., to identify, prevent, and ameliorate risks to health in that population) and the limitations on the power of the state to constrain the autonomy, privacy, liberty, or other legally protected interests of individuals for the protection and promotion of community health. (p. 4)

Descriptions of the law’s relevance to public health have also been stable and settled. For Hamlin (39), “[t]he law is a resource which must be used with all other resources such as health education, trained personnel, adequate facilities, and sufficient funds to accomplish the proper organization and operation of our health programs” (p. 1737). Gostin (32), similarly, proposes the “core idea” that “statutes, regulations, and litigation can be pivotal tools for creating the conditions for people to lead healthier and safer lives” (p. 2,837). Furthermore, the vision of how law fits into the work of public health professionals does not change. Hamlin (39) says, “[I]t is necessary that public health workers have a framework of understanding within which they may recognize, analyze, and understand their specific legal powers and problems” (p. 1737). Grad’s (36) first edition had a forward by Surgeon General Luther Terry, who hoped that the book would “serve as a common framework between health professionals and their legal advisors” (p. vi). Gostin (33) expanded the audience to include legislators, judges, and the “informed lay public,” but the aim is the same: that everyone “study and understand” the “theory and definition of public health law,…its principal analytical methods, and…its dominant themes” (pp. xxi–xxii).

Thus has public health law been consistently seen as a valid component of public health but one that was conducted by lawyers and that was relevant to public health professionals because of their need for legal support in their roles as public officials, law enforcers, or advocates for healthy public policy. The view that public health law is the province only of lawyers misses the fact that public health laws are commonly conceived, promoted, administered, and evaluated by public health professionals and others without JD degrees. To recognize an additional facet of public health law, one not primarily within the professional jurisdiction of lawyers, we henceforth refer to this traditional lawyer-centric portion of public health law as “public health law practice.” We define public health law practice as the application of professional legal skills in the development of health policy and the practice of public health, though any of the historical definitions of the field would do just as well for purposes other than the distinction we make in this article. Lawyers in public health law practice play at least three important roles: counsel, representation, and research. We do not suggest that this traditional component of public health law is unimportant. On the contrary, we believe legal expertise is essential in all its forms for the success of the public health enterprise (29).

To be true to practice, the public health lawyer’s role as a counselor should be broadly conceived. Within a strictly defined lawyer-client relationship, lawyers provide legal information, analysis, and advice (52). Government lawyers provide counsel to health officials (though sometimes it may be unclear whether the lawyer’s “client” is the elected body, a health officer, or an attorney general or other legal officer). Public health lawyers also work for nongovernmental organizations, but many do not represent clients in a strict sense. Some, such as lawyers at the Network for Public Health Law, the CDC’s PHLP, and ChangeLab Solutions, understand their counseling role as one of technical assistance. They provide legal information, including interpretation of the law, training, and strategic consultation. They often draft model laws, ordinances, regulations, or policies. Their goal is to build the capacity of public health practitioners and other community leaders to use the law to solve problems and improve population health outcomes. They do not, however, regard their consumers as clients and disclaim any intent to provide formal legal advice. Even further along the spectrum are lawyers who could best be described as working for the cause, whether it be tobacco control, a human rights approach to public health, or controlling obesity. Their counseling role centers on strategy and tactics to further specific legal and policy goals.

Representation—speaking for a client in legal and other fora—also takes many forms in public health law practice. For lawyers representing health agencies or other actual clients, it includes litigation. Although opinion and evidence are mixed on the value of impact litigation as a public health tool (62), litigation to enforce or defend public health laws and regulations is a staple of contemporary public health practice (52). Cause lawyers and academics also take part in litigation, typically by filing amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) legal briefs to bring relevant information before a court that the actual parties to a case may not be willing or able to supply. Lawyers appear before legislative committees, regulatory agencies, or other policy-making entities to provide information or lobby as the client’s status and wishes dictate. Cause lawyers often take leading roles in advocating for policies in their domains, engaging in community organizing, lobbying, and other activities to advance the cause. Even academics, in their writing in law journals, usually perceive themselves as combining research with some level of cause representation.

Research in public health law practice is diverse. In public health practice settings and academic work, legal research often takes the form of the collection and analysis of law to characterize the conduct it prescribes (“What are the rules?”) (25) or to answer specific legal questions (“Can x do y?”) (41). Legal research is conducted to map the content and distribution of law across jurisdictions (i.e., 50-state assessments) (50). Lawyers in both practice and academic settings help develop policy; lawyers conceptualize new regimes, such as the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, develop model laws, and draft the statutes and regulations that give policies their form. Lawyers, particularly those in academia and nongovernmental public interest organizations, take on the job of normative framing and analysis (85). In the face of well-organized efforts to limit public health legal authority (63), this function is more important than ever. As the IOM (44) observed, “Discussing the law and public policy is not possible without addressing the societal context—the national and community values, norms, and popular attitudes (i.e., toward government, toward public health) and perspectives that influence American policymaking and Americans’ understanding of the ‘good life’” (pp. 23–24). Public health legal research ranges from defining a vision of the good to setting the optimal fine for doing bad.

“LEGAL EPIDEMIOLOGY”

Public health law practitioners work along side public health officials, other government executives, legislators, and social activists, who in a broad sense have all come to treat law as an essential and normal tool of public health. This public health law practice work is essential to, but is also substantially assisted by, epidemiology, etiology, and scientific research on the impact of laws and legal practices on public health. From the development or selection of policies, through their enforcement, to decisions about whether a particular law should be recommended for wide adoption or repeal, public health law should meet the same standards of evidence and evaluation required for other modes of intervention and should be studied with the same scientific rigor as other social and environmental factors related to health (9). Research and policy development focused on law’s health effects, particularly research evaluating legal interventions, have been crucial to our national public health successes and, for several reasons, should be understood as integral components of public health law. Public health law is not only the work of lawyers. It is just as much a part of the work of public health scientists and practitioners.

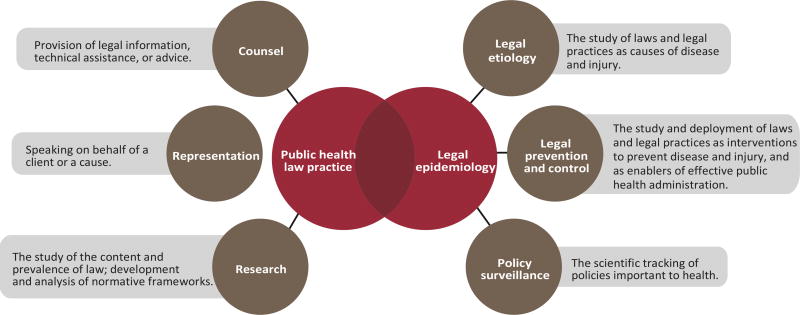

The work of conceptualizing, implementing, and evaluating laws to change behaviors and environments entails using the same scientific skills and methods used in the deployment of other modes of intervention in public health. We call this legal epidemiology, defined as the scientific study of law as a factor in the cause, distribution, and prevention of disease and injury in a population. Within those bounds, we identify these three components: Legal prevention and control, the study and application of laws and legal practices as interventions to prevent disease and injury and as enablers of effective public health administration; Legal etiology, the study of laws and legal practices as causes of disease and injury; and Policy surveillance, the ongoing, systematic collection, analysis, and dissemination of information about laws and other policies of importance to health (20).

Legal prevention and control encompasses the oldest and most well-developed practices of legal epidemiology. Using legal tools to change unhealthy behaviors and environments is routine. The scientific literature is rich with studies that evaluate the impact and implementation of interventional public health laws or that study the factors that influence their enactment. Burris&Anderson (13) reviewed the history of interventional public health law research in several important topic areas. Like other recent studies (56, 71), their account challenges the perception that using law for public health purposes is generally unpopular or prone to controversy. It also makes two more basic points about the field. First, in domains such as alcohol, auto safety, and tobacco control, the United States has invested in creating the infrastructure of researchers, data, and methods that makes first-rate scientific evaluation possible. Second, this solid scientific work has made a material contribution to the widespread implementation of evidence-based public health law interventions. Although there are exceptions (for example, motorcycle helmet laws and alcohol excise tax rates), laws that have been found to be effective in systematic reviews also tend to have been widely adopted by law makers (57). Although not every legal intervention is evaluated in a timely and rigorous manner, there is no question of the feasibility and impact of this kind of research.

Legal prevention and control includes the implementation and effects of laws establishing the powers, duties, and jurisdiction of health agencies law (16, 18). Variation in this legal architecture across states and localities amounts to a long-term experiment in public health management that has been too seldom studied. Developing and enforcing regulations are among the ten essential health services (81), which points to the importance of individual and organizational legal capacity (16). Whether and how actors in public health agencies understand and apply the law, and have the resources they need to do it, will influence the agencies’ outputs and outcomes. To date, health system legal capacity and its effects have not been sufficiently studied. The ability of researchers and practitioners to conduct and apply research in this domain is essential for the proper use of law to promote safer environments and behaviors to assure that health agencies have an optimal legal design and that their powers are being wielded effectively.

Legal etiology is a less-developed concept than legal prevention and control but is, if anything, even more important. It is the study of law’s incidental or unintended effects on health. Not all law that influences health falls within the traditional boundaries of “health law.” Most laws are proposed, enacted, and enforced with little or no thought to health, but many laws and policies can have a powerful health impact. For example, immigration policy influences health and access to health care among undocumented immigrants (53), drug laws and law enforcement practices can exacerbate HIV risk behavior among drug users (14), unemployment compensation laws may attenuate the effects of unemployment on adult and child health (46), and zoning may determine whether consumers can conveniently buy fresh fruits and vegetables (54). The realization that a wide range of laws and policies can have unintended and unexpected health effects was a primary impetus for Health Impact Assessment and Health in All Policies approaches (21, 45). More broadly, law is a vital focus for research addressing social determinants of health—social and environmental factors outside of traditional medical care and public health intervention that impact population health over the entire life course (7, 24). As the IOM (44) put it,

The health of a nation is shaped by more than medical care, or by the choices that individuals make to maintain their health, such as quitting cigarette smoking or controlling diabetes. The major contributors to disease—risk factors under the control of individuals (e.g., obesity, tobacco use), exposure to a hazardous environment, or inadequate health care—are themselves influenced by circumstances that are nominally outside the health domain, such as education, income, and the infrastructure and environment that exist in workplaces, schools, neighborhoods, and communities. (p. 73)

Efforts to theorize social determinants (3) and to prescribe reforms (5) have been impressive and important (8,49), but our health research investments remain biased toward the individual risk factors and proximate causes of death. The RWJF’s Commission to Build a Healthier America (7) and its new Culture of Health Initiative (65) build on “an accumulating critical mass of knowledge in social and biomedical sciences,” showing associations among and elucidating pathways between thelevelanddistributionofhealthononehandandanarrayofsocialfactorsontheother (7, p.382). This kind of support, and more, is crucial because moving the evidence base from association to causation, and from the proximal to the upstream, is a huge challenge. Because law plays such an important and pervasive role in structuring environments and behaviors and beliefs (15, 47, 51), research under the heading of legal etiology is crucial to charting a course of practical reform. It encompasses law’s structural role in shaping the level and distribution of health in a community (18, 44), law’s contribution to cultural beliefs about how health is produced, protected, and distributed (51, 65, 76), and how we can use legal interventions, such as enforcing healthy housing codes, to improve health and health equity.

Surveillance in public health is the means by which people who are responsible for public health track the occurrence, antecedents, time course, geographic spread, consequences, and nature of disease, injury, and risk factors among the populations they serve (10). If law matters to health, policy makers, officials, and the public need basic information about what law requires and where it applies, a process known as policy surveillance. If the impact of law is to be empirically assessed, the law must be measured in a way that creates data for evaluation. Doing so entails scientific methods of (usually) quantitative coding (1) but also necessitates the collection of longitudinal legal data because the most robust evaluation designs require variation in time as well as space (84). Scientific coding procedures, combined with modern information technology, allow the efficient publication of digitized data to the Internet. Publication supports the rapid diffusion of policy information to health professionals, policy makers, and the public.

The impulse to track the law in a complex federal system is an old one (37,55). A recent Internet scan turned up hundreds of web pages reporting current 50-state assessments of health law (66). Only in a very few instances, however, is this legal information systematically or scientifically collected, coded, or published to capture change over time or to provide data suitable for use in evaluation (see http://iphionline.org/homepage/data-it/). The adoption of policy surveillance as a standard practice of public health, which the IOM has encouraged (44), will bring the traditional legal practice of multijurisdictional mapping into line with how public health monitors other phenomena of interest and will help promote more rapid diffusion of recommended policies and promising innovations.

TRANSDISCIPLINARY PUBLIC HEALTH LAW: IMPLICATIONS

The essence of a transdisciplinary model is true integration of theories, methods, and tools for the purpose of better addressing social problems (2, 73). Transdisciplinary research is not merely lawyers and scientists pursuing the same public health goals in an independent or interactive manner. Rather, in a transdisciplinary model, professionals “representing different fields work together over extended periods to develop shared conceptual and methodologic frameworks that not only integrate but also transcend their respective disciplinary perspectives” (75, p. S79). Figure 1 depicts a union of disciplines that is already producing the intellectual products of a transdisciplinary endeavor, including “new hypotheses for research, integrative theoretical frameworks for analyzing particular problems, novel methodological and empirical analyses of those problems, and, ultimately, evidence-based recommendations for public policy” (74, p. S22).

Figure 1.

Transdisciplinary public health law.

To integrate law and science in public health, lawyers, scientists, and public health institutions must all change. Lawyers in a Transdisciplinary practice must embrace and become competent in the language, concepts, and frameworks of public health science and tune their work to its maximum scientific value. Thus, for example, policy surveillance draws on both traditional legal research and scientific methods within a public health practice concept of surveillance (1). Lawyers must be able to conceptualize and communicate in behavioral and social scientific terms how law achieves its effects (17). Lawyers can and should acquire the basic grasp of research methods and tools needed to bring their legal expertise to bear in Transdisciplinary evaluation research teams (83). As key links in the chain of translating evidence into policy, lawyers should participate in defining research needs and translating research knowledge into policy form.

Public health professionals must accept law as a mode of behavioral and environmental influence that can be scientifically theorized, measured, and manipulated like any other. The legal epidemiologist engages law as an important factor in health, understands that law shapes behavior and environments in ways that go beyond simple deterrence models, and avoids black-box studies that fail to take advantage of sociolegal and behavioral theories that account for the many ways that law affects behavior and the social and physical environment (17). The expeditious evaluation of deliberate legal health interventions is recognized as important, but so is the effort to understand how nonhealth laws contribute to poor health and health inequities. At its best, public health science is already transdisciplinary, drawing on fields as diverse as urban planning, economics, sociology, anthropology, and epidemiology. It is, in truth, a small step to incorporate a scientifically informed dimension of law.

A transdisciplinary practice requires structural changes in institutions, funding streams, and professional hierarchies (23). More than a decade ago, an IOM committee on public health education recommended that law and policy be strengthened in the public health curriculum to train lawyers, scientists, and health practitioners to transcend disciplinary boundaries (22). Progress has been limited. The reason, we suspect, is that law has continued to be taught, if at all, as public health law practice. While it is important for students to acquire a grasp of how the legal system operates, future public health practitioners and researchers need a solid grounding in legal epidemiology. The recent growth of JD/MPH programs is producing more lawyers who understand both cultures, filling the oft-expressed need of public health practitioners for lawyers who “get” public health. That does not address legal training for MPHs, which needs to be more substantial and more transdisciplinary in the ways we have outlined here. When it comes to training researchers, the goal should not be to build a large cohort of legal specialists within the health research world. The more useful aim is for all social and behavioral researchers to have the willingness and competence to study law as a factor when it is present in a given health phenomenon. This goal is consistent with the view that law is not fundamentally different from other social and environmental influences on health. To continue the progress of the past few years, the model of the JD/MPH suggests the value of developing JD/PhD programs to train researchers who can take the lead in the further development of legal epidemiology.

Public health law practice has never been better supported. Between the RWJF-sponsored programs (40), CDC’s PHLP (31), and the many academic and community-based topical health law centers, health professionals, agencies, advocates, the media, and engaged citizens have never had so many lawyers they could contact for legal expertise. However, there has been little progress in increasing dedicated, qualified legal counsel for health agencies or in finding a feasible model for doing so among the many small agencies that make up local public health (44, 58). Like many other public health services, public health law relies on discretionary foundation and government funding that could be redirected at any time.

Legal epidemiology remains too low a priority among research funders. In alcohol and auto safety, we have outstanding examples of how to build an infrastructure of data and career opportunities that can lead to rigorous methods and compelling results (13). Sustained funding came from the NIH, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, and nongovernmental organizations such as the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety and RWJF. But the NIH’s support of legal evaluation has been neither systematic nor comprehensive. Perhaps the most important example of this inconsistency has been in the lack of NIH emphasis on rapidly evaluating state and local public health law innovations. These initiatives can deliver “doses” of treatment to tens or hundreds of millions of people if they are rapidly scaled up, and yet they receive far less evaluation funding from the NIH than do individualized behavioral interventions delivered to just a few thousand people by peers or clinicians. The CDC, too, could have a broader impact on the evidence base by organizing its investments in legal epidemiology more productively. Although the CDC appreciates and invests in legal and policy research, projects are often farmed out in small contracts designed to meet short-term needs of specific programs. Opportunities include more actively coordinating policy surveillance and other mapping work, leading the charge for standard methods and tools that support higher quality and easier data sharing and bringing more transdisciplinary lawyers into the work.

Transdisciplinary public health law represents an opportunity for more effective collaboration to advance public health through law and policy. Efforts to regulate behavior and environments have been opposed both by influential scholars (26) and by industries that do not wish to be constrained; courts have issued decisions that cast doubt on the scope of public health’s authority to issue innovative rules such as the New York City soda portion cap (34). A federal appellate panel ruling on graphic cigarette warning labels went so far as to question whether the government had any interest in influencing consumption of otherwise legal products (68). Preemption—the authority of state or federal lawmakers to bar lower governmental units from rule-making in particular topics—is too often used to stifle innovation and regulation that respond to local needs (64). The majority of Americans seem to support vigorous use of the law to improve health (56), but public consensus on specific policies does not always translate into the election of officials ready to promote and implement them.

In both the courts of public opinion and the courts of law, public health needs to argue more effectively for resources and collective action (85). A transdisciplinary model links research, advocacy, and practice more organically so that (a) when policy makers face problems, they have the evidence and expertise they need to adopt proven interventions or to design plausible innovations; (b) advocates promoting a specific course of policy action have the tools they need to engage and inform stake holders, including the knowledge of policy trends and where similar policies have been adopted so far; (c) practitioners charged with enforcing policy can draw on methods and insights tested by implementation research; and (d) when public health law practitioners are assessing legal risks or defending a measure in court, they have the scientific evidence they need readily available. The organic links contemplated in a transdisciplinary model can, by these means, shorten the time required to go from intuitive problem solving in the face of new problems to the identification and widespread adoption of those legal innovations that stand the test of evaluation: better health faster.

A transdisciplinary model is also well suited to the challenge of reclaiming public health’s political legitimacy and legal weight. For many reasons, including diligent ideological campaigning, it is not difficult for opponents to cast even a proven health measure as one more bumbling, paternalistic government intrusion into individual rights or efficient markets (11). The social and political campaign to delegitimize and defund regulation has moved in parallel with a legal effort to weaken the legal basis for public health action, most notably through a drastic expansion of First Amendment protections for corporations (59). Lawyers, including academic public health lawyers, can develop normative frameworks (85) and legal strategies (61, 77) to begin to reverse these trends. Informed by social science (and bitter experience), we in public health can learn to broaden our arguments. Public health advocacy traditionally speaks in the moral realm of preventing harm and reducing inequities. These kinds of arguments tend to be well received by liberals. As the psychologist Jonathan Haidt has shown, a broader moral pallet—including appeals to loyalty, sanctity, and liberty—is needed to reach political conservatives and independents (38). RWJF’s Culture of Health initiative is an ambitious effort to restore to the American mindset an appreciation for health and the commitments necessary to achieve it. Law and policy, as a way of expressing our most important values, will play an important part in the cultural change we so badly need.

CONCLUSION

Four major IOM reports over 25 years have lamented the state of public health laws, the practice of law, the training of public health officials in law, and the access of health officials to quality legal advice (22, 42–44), and this was all during a renaissance in the field. We have argued that the continued marginalization of law in public health research, practice, and funding flows from a narrow view of the field as a domain reserved for lawyers doing legal work. We have described a more inclusive, interdisciplinary model of public health law, linking both its legal and scientific elements. Policy development, surveillance, implementation, and evaluation are all in the normal job description of public health practitioners and researchers, and without them public health would have no impact. Breaking down enduring cultural, disciplinary, and resource barriers will promote full recognition of and an optimal role for law in public health.

SUMMARY POINTS.

Public health law encompasses both the (a) application of professional legal skills in the development of health policy and the practice of public health and (b) the scientific study of law as a factor in the cause, distribution, and prevention of disease and injury in a population.

A transdisciplinary model of public health law, integrating legal and scientific elements of the work and the workforce, will lead to more robust evidence of the law’s impact on health and more rapid diffusion of effective policies.

Legal health interventions that “treat” millions should be more rigorously and rapidly evaluated.

Funding for policy surveillance and other legal and policy mapping work should be better coordinated to maximize usefulness and avoid duplication.

Standard methods and tools will support better data, data sharing, and higher-quality legal and policy analysis and evaluation.

Study of the law’s role in structuring the physical and social environments is a neglected area and will particularly benefit from a transdisciplinary approach.

Training of lawyers, policy professionals, public health practitioners, and scientists should embody and support a transdisciplinary perspective.

Acknowledgments

Work on this article was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under CDC Collaborating Agreement Number CDC-RFAOT13-1302. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and not those of the CDC or RWJF.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Professor Burris is a Partner in Legal Science, LLC, a company that provides software and research services for policy surveillance. The authors are not aware of any other affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Anderson E, Tremper C, Thomas S, Wagenaar AC. Measuring statutory law and regulations for empirical research. See Ref. 83. 2013:237–60. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balsiger PW. Supradisciplinary research practices: history, objectives and rationale. Futures. 2004;36:407–21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkman L, Kawachi I, editors. Social Epidemiology. New York: Oxford Univ. Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman ML. Defining the field of public health law. DePaul J. Health Care Law. 2013;15:45–92. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blankenship KM, Bray S, Merson M. Structural interventions in public health. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl. 1):S11–21. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyce LL. The Health Officers’ Manual and Public Health Law of the State of New York. Albany: Matthew Bender; 1902. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2011;32:381–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braveman PA, Egerter SA, Woolf SH, Marks JS. When do we know enough to recommend action on the social determinants of health? Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010;40:S58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brownson RC, Chriqui JF, Stamatakis KA. Understanding evidence-based public health policy. Am. J. Public Health. 2009;99:1576–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buehler JW. Surveillance. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, editors. Modern Epidemiology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. pp. 459–80. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burris S. The invisibility of public health: population-level measures in a politics of market individualism. Am. J. Public Health. 1997;87:1607–10. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.10.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burris S, Anderson E. Making the case for laws that improve health: the work of the Public Health Law Research National Program Office. J. Law Med. Ethics. 2011;39(Suppl. 1):15. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2011.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burris S, Anderson E. Legal regulation of health-related behavior: a half century of public health law research. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 2013;9:95–117. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burris S, Blankenship KM, Donoghoe M, Sherman S, Vernick JS, et al. Addressing the “riskenvironment” for injection drug users: the mysterious case of the missing cop. Milbank Q. 2004;82:125–56. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burris S, Kawachi I, Sarat A. Integrating law and social epidemiology. J. Law Med. Ethics. 2002;30:510–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2002.tb00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burris S, Mays GP, Scutchfield FD, Ibrahim JK. Moving from intersection to integration: public health law research and public health systems and services research. Milbank Q. 2012;90:375–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00667.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burris S, Wagenaar A. Integrating diverse theories for public health law evaluation. See Ref. 83. 2013:193–214. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burris S, Wagenaar AC, Swanson J, Ibrahim JK, Wood J, Mello MM. Making the case for laws that improve health: a framework for public health law research. Milbank Q. 2010;88:169–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00595.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.CDC (Cent. Dis. Control and Prev.) Ten great public health achievements—United States, 1900–1999. MMWR. 1999;48:241–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chriqui JF, O’Connor JC, Chaloupka FJ. What gets measured, gets changed: evaluating law and policy for maximum impact. J. Law Med. Ethics. 2011;39(Suppl. 1):21–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2011.00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins J, Koplan JP. Health impact assessment: a step toward health in all policies. JAMA. 2009;302:315–17. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: Natl. Acad. Press; 2003. Comm. Educ. Public Health Prof. 21st Century. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Facilitating Interdisciplinary Research. Washington, DC: Natl. Acad. Press; 2004. Comm. Facil. Interdiscip. Res., Natl. Acad. Sci., Natl. Acad. Eng., Inst. Med. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Comm. Soc. Determ. Health, WHO (World Health Org.) Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: WHO; 2008. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43943/1/9789241563703_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Courtney B, Sherman S, Penn M. Federal legal preparedness tools for facilitating medical countermeasure use during public health emergencies. J. Law Med. Ethics. 2013;41(Suppl. 1):22–27. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epstein RA. Let the shoemaker stick to his last: a defense of the “old” public health. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2003;46:S138–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erickson DL, Gostin LO, Street J, Mills SP. The power to act: two model state statutes. J. Law Med. Ethics. 2002;30:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freund E. The Police Power, Public Policy and Constitutional Rights. Chicago: Callaghan; 1904. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frieden TR. Government’s role in protecting health and safety. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1857–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1303819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodman RA. Law in Public Health Practice. New York: Oxford Univ. Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodman RA, Moulton A, Matthews G, Shaw F, Kocher P, et al. Law and public health at CDC. MMWR. 2006;55(Suppl. 2):29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gostin LO. Public health law in a new century: part I: law as a tool to advance the community’s health. JAMA. 2000;283:2837–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.21.2837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gostin LO. Public Health Law: Power, Duty, Restraint. Berkeley: Univ. Calif. Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gostin LO, Reeve BH, Ashe M. The historic role of boards of health in local innovation: New York City’s soda portion case. JAMA. 2014;312:1511–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.12498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grad F. Public Health Law Manual. 3 New York: Am. Public Health Assoc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grad FP. Public Health Law Manual: A Handbook on the Legal Aspects of Public Health Administration and Enforcement. New York: Am. Public Health Assoc; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greve CH. Provisions of State laws governing local health departments. Public Health Rep. 1953;68:31–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haidt J. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Pantheon; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamlin RH. Public health law or the interrelationship of law and public health administration. Am. J. Public Health Nation’s Health. 1961;51:1733–37. doi: 10.2105/ajph.51.11.1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hodge JG, Jr, Barraza L, Bernstein J, Chu C, Collmer V, et al. Major trends in public health law and practice: a network national report. J. Law Med. Ethics. 2013;41:737–45. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hodge JG, Jr, Pulver A, Hogben M, Bhattacharya D, Brown EF. Expedited partner therapy for sexually transmitted diseases: assessing the legal environment. Am. J. Public Health. 2008;98:238–43. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The Future of Public Health. Washington, DC: Natl. Acad. Press; 1988. Inst. Med. [Google Scholar]

- 43.The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: Natl. Acad. Press; 2002. Inst. Med. [Google Scholar]

- 44.For the Public’s Health: Revitalizing Law and Policy to Meet New Challenges. Washington, DC: Natl. Acad. Press; 2011. Inst. Med. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kickbusch I, McCann W, Sherbon T. Adelaide revisited: from healthy public policy to Health in All Policies. Health Promot. Int. 2008;23:1–4. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dan006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Komro KA, Burris S, Wagenaar AC. Social determinants of child health: concepts and measures for future research. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2014;1:432–45. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Komro KA, O’Mara RJ, Wagenaar AC. Perspectives from public health. See Ref. 83. 2013:49–86. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koyuncu A, Kirch W. Public health law and the legal basis of public health. J. Public Health. 2010;18:429–36. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lavizzo-Mourey R, Williams DR. Strong medicine for a healthier America: introduction. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010;40:S1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lehman JS, Carr MH, Nichol AJ, Ruisanchez A, Knight DW, et al. Prevalence and public health implications of state laws that criminalize potential HIV exposure in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:997–1006. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levitsky SR. Integrating law and health policy. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 2013;9:33–50. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lopez W, Frieden T. Legal counsel to public health practitioners. See Ref. 30. 2007:199–221. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martinez O, Wu E, Sandfort T, Dodge B, Carballo-Dieguez A, et al. Evaluating the impact of immigration policies on health status among undocumented immigrants: a systematic review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health. 2013;17:947–70. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9968-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mayo ML, Pitts SB, Chriqui JF. Associations between county and municipality zoning ordinances and access to fruit and vegetable outlets in rural North Carolina, 2012. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E203. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.130196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moldenhauer RM, Greve CH. General regulatory powers and duties of state and local health authorities. Public Health Rep. 1953;68:434–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morain S, Mello MM. Survey finds public support for legal interventions directed at health behavior to fight noncommunicable disease. Health Aff. 2013;32:486–96. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moulton AD, Mercer SL, Popovic T, Briss PA, Goodman RA, et al. The scientific basis for law as a public health tool. Am. J. Public Health. 2009;99:17–24. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.130278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.NACCHO (Natl. Assoc. County City Health Off.) 2010 National Profile of Local Health Departments. Washington, DC: NACCHO; 2011. http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/profile/resources/2010report/upload/2010_profile_main_report-web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Outterson K. Higher First Amendment hurdles for public health regulation. N.Engl.J.Med. 2011;365:e13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1107614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parker L, Worthington RH. The Law of Public Health and Safety and the Powers and Duties of Boards of Health. Albany, NY: Bender; 1892. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parmet W. Populations, Public Health, and the Law. Washington, DC: Georgetown Univ. Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parmet WE, Daynard RA. The new public health litigation. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2000;21:437–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parmet WE, Jacobson PD. The courts and public health: caught in a pincer movement. Am. J. Public Health. 2014;104:392–97. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pertschuk M, Pomeranz JL, Aoki JR, Larkin MA, Paloma M. Assessing the impact of federal and state preemption in public health: a framework for decision makers. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2013;19:213–19. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182582a57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Plough AL. Building a culture of health: a critical role for public health services and systems research. Am. J. Public Health. 2015;105(Suppl. 2):S150–52. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Presley D, Reinstein T, Burris S. Resources for policy surveillance: a report prepared for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Law Program. 2015 Leg. Stud. Res. Pap. 2015-09, Public Health Law Res., Phila. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2567695.

- 67.Robert Wood Johnson Found. William Foege Q&A: public health law. New Public Health (blog) 2012 Oct 11; http://www.rwjf.org/en/culture-of-health/2012/10/william_foege_q_ap.html.

- 68.R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company v. Food and Drug Adm. F.3rd, D.C. Circuit. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rothstein MA. Rethinking the meaning of public health. J. Law Med. Ethics. 2002;30:144–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2002.tb00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shattuck L. Report of a General Plan for the Promotion of General and Public Health Devised, Prepared and Recommended By the Commissioners Appointed Under a Resolve of the Legislature of Massachusetts, Relating to a Sanitary Survey of the State. Boston: Dutton and Wentworth; 1850. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Simon PA, Chiang C, Lightstone AS, Shih M. Public opinion on nutrition-related policies to combat child obesity, Los Angeles County, 2011. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E96. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stah lD., editor. Public Health Laws of Pennsylvania: A Study of the Laws of the Common wealth of Pennsylvania Relating to Public Health. Pittsburgh, PA: Univ. Pittsburgh Sch. Law; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stember M. Advancing the social sciences through the interdisciplinary enterprise. Soc. Sci. J. 1991;28:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stokols D, Fuqua J, Gress J, Harvey R, Phillips K, et al. Evaluating transdisciplinary science. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2003;5:S21–39. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001625555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stokols D, Hall KL, Taylor BK, Moser RP. The science of team science: overview of the field and introduction to the supplement. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008;35:S77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stryker R. Law and society approaches. See Ref. 83. 2013:87–108. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sunstein C, Thaler R. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Teret SP, Webster DW, Vernick JS, Smith TW, Leff D, et al. Support for new policies to regulate firearms. Results of two national surveys. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339:813–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809173391206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tiedeman CG. A Treatise on the Limitations of Police Power in the United States: Considered from Both a Civil and Criminal Standpoint. St. Louis: F.H. Thomas Law; 1886. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tobey J. Public Health Law: A Manual of Law for Sanitarians. New York: Commonw. Press; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Turnock BJ, Handler AS. From measuring to improving public health practice. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 1997;18:261–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vernick JS, Webster DW, Hepburn LM. Effects of Maryland’s law banning Saturday night special hand guns on crime guns. Inj. Prev. 1999;5:259–63. doi: 10.1136/ip.5.4.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wagenaar A, Burris S, editors. Public Health Law Research: Theory and Methods. San Francisco: Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wagenaar AC, Komro KA. Natural experiments: research design elements for optimal causal inference without randomization. See Ref. 83. 2013:307–24. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wiley LF, Parmet WE, Jacobson PD. Adventures in nannydom: reclaiming collective action for the public’s health. J. Law Med. Ethics. 2015;43:73–75. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]